Marco Santagata, Dante: The Story of His Life (2012).

Good Reads meta-data is 485 pages rated 3.74 by 168 litizens.

Genre: Biography.

DNA: Italia.

Verdict: Finely shifted

Tagline: Synergy of fact and fiction.

Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) aspired to greatness, beginning that quest by changing his name from ‘Durante’ to ‘Dante’ to imply a connection to a once great family name in Florence. This change is characteristic of the aspirations and method of the man.

The Guelph and Ghibelline dispute dominated social and political life in Dante’s time and place. While Florence was identified with the Guelph cause, occasionally there was a swing to the Ghibellines. A victorious sect would banish its enemies, seize their property, ransom its members, and depending on God’s will murder them en masse! Dante had no interest in this bloodbath but he could not ignore it. This conflict started in the 11th Century and continued for centuries, with neither a definitive beginning nor end.

It arose from the clash of secular and sectarian authority, that is, over who appointed bishops: the Pope (Guelphs) or the Holy Roman Emperor (Ghibellines). That doctrinal cleavage aggregated a great many other political, social, and personal motivations. Each of those unities had divisions with its ranks, for example, there were black and white stripes among the Guelphs. Regional and dynastic loyalties led to conflict among Ghibellines. And so on and on. It all seemed cataclysmic to the participants and it is meaningless to us, like so many murderous religious disputes.

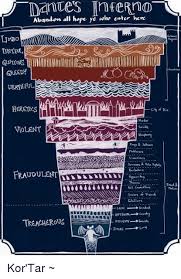

Autobiographical references are to be found in all of Dante’s works, as per the custom of the time, and a systematic examination of these references indicates that they pad his resumé with fictions. Or as the author delicately puts its, Dante did not draw an exact line between fiction and fact. This penchant is most visible, of course, in the longest work where there is the largest number of such autobiographical selfies, the Commedia, where he meets many deceased relatives, friends, and mentors who were in fact no such thing. He claims many associations with people to bathe in their reflected glory borne from social status, poetic achievement, or civic heroism, who had nothing to do with him: including, it seems likely, Beatrice herself. To illustrate his free use of fiction, he peopled the Commedia with more than one person who was still alive, giving Dante the opportunity to pass his judgements on those people, which he certainly did, though not always consistently. On this inconsistency see below.

About this point I paused once again to ponder the parallels between Dante and Machiavelli. I put the question to Google AI on 7 July and got this response: ‘Both Dante and Machiavelli were Florentines living during a period of political and social upheaval. However, their responses to these challenges differed significantly, with Dante focusing on moral and religious ideals and Machiavelli prioritizing practical political strategies.’

Hmm, what underlies this anodyne generalisation is this. It refers only to their written work. In Dante’s case it was De Monarchia (1313) in which he concluded that a only universal monarch above and apart from all sectional, regional, sectarian division could bring and insure peace: Big Brother with a crown. Whereas in the Prince, Machiavelli described what he saw and tried to find patterns in the instances of politics he observed.

So far, well, so good, but there is more. In his life Machiavelli worked for a Republican government: his texts, including the Prince for those with eyes to see, shows that preference. He remained true to that conviction throughout his tenuous exile. (The story of writing the Prince for a prince and presenting it to him, is one of his elaborate jokes that has passed into reality by repetition, in my opinion, a minority one to be sure, but right all the same.)

In his own exile Dante behaved according to the stereotype of Machiavellian and Machiavellianism, currying favour by trimming, temporising, and tacking with the prevailing, local political winds. One day he was ardent Guelf, and a week later a born Ghibelline, then a born-again White Guelf, and so on. He did not trust to prayer alone but to his wit and wile to survive. This variation is shown in the Commedia where inconsistent judgements are rendered on the long journey. Inconsistent, yes, and at times deceitful as this biographer shows ever so delicately. Dante did all of this balancing on the ball of fortune in a world of confusion, conflict, and – some of the time – chaos while living by the grace and favour of hosts.

And Exhibit B is that Dante’s name and the Commedia went onto the Papal Index, just like Machiavelli. That was in retaliation for all those popes whom he had sent to Hell!

Yet Dante’s name has not entered the lexicon as an adjective or noun for deceit, dissimulation, or duplicity. Why is that? When you can answer that question, let me know.

The point is not to condemn Dante’s survival instinct, but to highlight the opprobrium visited on the blameless Machiavelli. By the way, as far I can tell, Machiavelli does not mention Dante’s De Monarchia in his History of Florence, though he does mention the man himself, his trials and tribulations. Nor does he mention Dante at all in The Prince. This vacuum has generated a speculative literature in which Machiavelli’s silence is made to speak! On that, perhaps, more another time.

For some reason in the mysteries of little grey cells pondering this conundrum brought to mind Gerald Durrell’s description of a jellyfish as a process. The fish is itself 95% water and it is immersed in water. It is but 5% out of that water. To think of it as separate from water is to misconceive it entirely. It is rather like abstracting a dancer from the dance, leaving only footsteps on the stage. Something like this applies to Machiavelli for whom politics was a process and abstracting from it is a distortion. Think about that. I know I will.

Returning to the poet, none of his personal peccadilloes. proclivities, and penchants, detracts a single iota from the Commedia; its grandeur is sui generis and self evident. We heard a translated reading from Paradise a few years ago, in of all places, Redfern, and were transported to another place. Mind you the reader had a voice of smoked honey that made it easy to listen. The translation was by John Ciardi whom I met years ago at another poetry reading.

This biography is an exemplar in the careful, systematic, and critical way it pieces together the story of Dante’s life. That makes the going slow, true, but also, and more importantly, sure. However, it lacks a final summation chapter. It is weighted to his activities more than his creativity, and perhaps that is why the abrupt ending. Still I would have liked to learn more about, e.g., how the Commedia got on the Librorum Prohibitorum of forbidden books. And more about that adjective Divina, which he did not use.

This reading reminded me I read a krimi some time ago that features Dante himself in his role as Florentine Prior, a kind of magistrate. There are several in this series and I will read another in due course.