Class, time for another quiz. Get those eggheads ready! Agitate those little grey cells!

In the 1860s, who…

1.negotiated treaties with foreign governments and corporations without any political authority?

2.created an elaborate parallel federal bureaucracy with no constitutional authority?

3.practiced state socialism?

4.monopolized trade?

5.seized private property to the tune of $30,000,000 in gold?

6.exercised the executive authority of a president without any political mandate?

7.abrogated habeas corpus in the pursuit of conscripts?

8.and did all of this over the area of Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, eastern Kansas, and Oklahoma to the loyal supporters of the Confederacy?

All those who said General William Sherman in his famous March to the Sea, on with the dunces’ caps and look at a map!

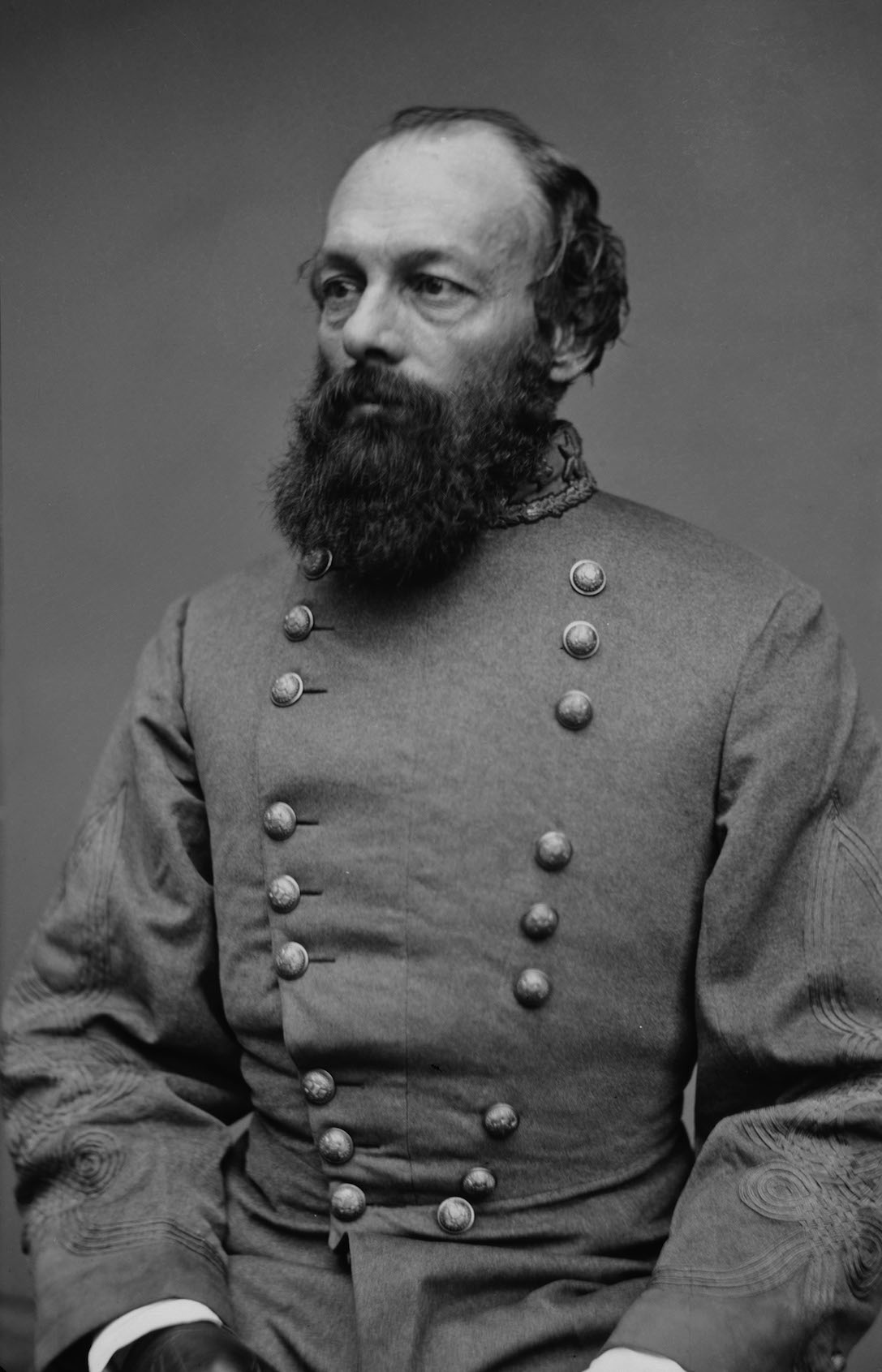

All of this was done for more than two years (1863-1865) by forty-year old full General Kirby Smith, of the Confederate States of America army. How that came to be, why it happened, what he did and how are laid out in this fascinating study of a corner of American political history quite unknown to this casual Civil War buff.

General Kirby Smith

General Kirby Smith

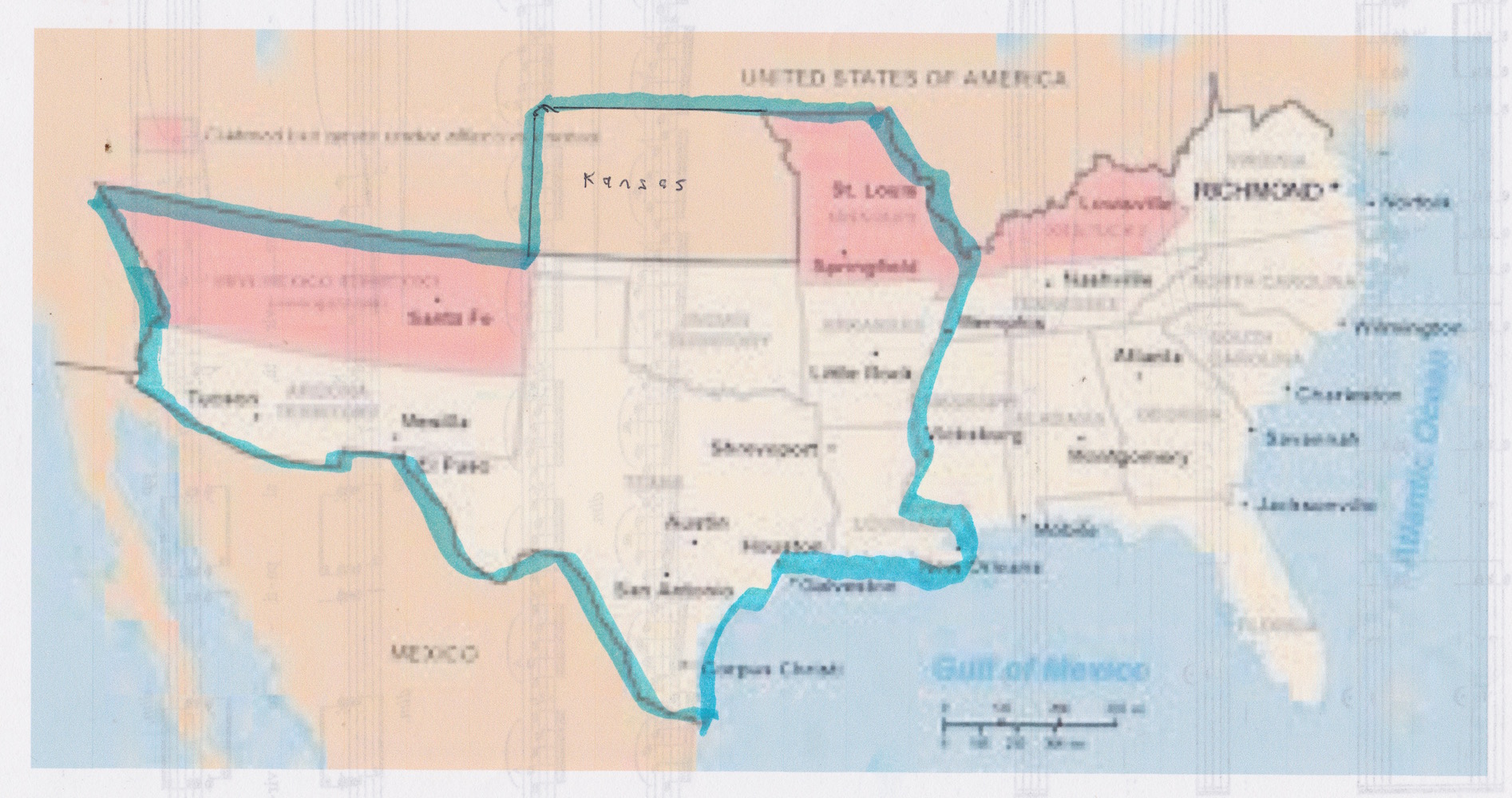

I had long known that the youthful General Smith had commanded Trans-Mississippi Confederacy though I was never quite sure I could find the Trans-Mississippi on a map. I now know it comprised four states (Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas) and four territories (Arizona, New Mexico, Kansas, and Indian [Oklahoma]).

The blue line encompasses the field of operations of the Department of Trans-Mississippi Confederacy.

The blue line encompasses the field of operations of the Department of Trans-Mississippi Confederacy.

His army, such as it was, was the last major force to lay down its arms in June 1865 as the news from the east made its way west. But knowing that was to know nothing of the detail.

After reading some other biographies of presidentials in the Civil War period I was reminded of Smith’s domain and decided to find a book about it. Pay dirt!

Not only does the book produce the goods on Smith and the Trans-Mississippi it makes the point that without the title or the legitimacy that goes with it, he exercised the prerogatives of a super-president unbalanced by a legislature and unchecked by a judiciary for two years. See that list of eight points above. If President Abraham Lincoln or President Jefferson Davis had done any of these, the opposition would have been great. Indeed, for what it is worth, Davis did none of them and Lincoln did only one, habeas corpus – he put a lot of people in jail indefinitely on the suspicion of sedition without trial. A lot. He provided a precedent for George W. Bush and Guantanamo Bay that was never cited!

First to that name ‘Trans-Mississippi’ for those who did not read Caesar’s ‘Gallic Wars’ ‘Cis-Alpine’ means on this – ‘cis’ – side of the Alps, and ‘trans’ means…? Yes, Class, on the other side of the Alps. Now apply that to the Mississippi.

No, Dunce, Caesar did not cross the Mississippi River at Rubicon! Do pay attention.

Cis-Mississippi is east of the Mississippi River and Trans-Mississippi is west of the Mississippi River. (Except in Des Moines Iowa where I repeatedly find on Skywalk maps that east and west are relative terms not fixed.) Now that we have nailed the name, let’s go to the man.

Kirby Smith (1824-1893), born in Florida, was a West Point graduate and a gentleman scientist whose collection of botanical specimens acquired while serving in frontier forts in Texas can still be seen in the of Natural History on the Mall. He served under Braxton Bragg in the Confederate Army of Tennessee and when his accomplishments made Bragg look bad, he removed him from command in one of this many fits of jealousy. Smith was thus available at the right time to go West in January 1863. The theatre he commanded was the biggest in space assigned to a general officer in either army and the means he had to defend it ranked the smallest on any measure. He said he liked a challenge, and off he went with a devil-may-care wink.

Within six months it got a harder. The Confederate stronghold at Vicksburg surrendered and in a few weeks the Mississippi River became a Federal lake, impassable to Confederates. Smith was now on his own, with very limited, very difficult communication with the Confederate government in Richmond. Intrepid individuals rowed skiffs, canoes, rafts, and logs across the Father of Waters bearing messages. They might wait weeks for Federal patrols on the River to move on, slacken, or be called away to a diversion before daring a night crossing. Anyone who has seen the current in the Mississippi above the Delta knows that this is a life-risking exercise. Many messages and some messengers were lost to the River, to Union patrols, and to self-preserving second thoughts.

At first Smith dutifully asked for instructions case-by-case from Richmond but after July he sought a carte blanche which in a series of agonising messages travelling this long, dangerous, uncertain route from Richmond to his headquarters in Shreveport Louisiana or Marshall Texas President Davis did not say ‘no’ to the request but then did not say ‘yes’ either. For equivocating, President Davis could give the Japanese lessons.

Finally, Smith just focused on Davis’s sentences that seemed to authorise him to do what Smith deemed necessary and ignored all the qualifications, asides, limitations, hedges, cross-references, hesitations, definitions, and the fog of indecision that Davis’s pen exuded. One reason Davis obfuscated was that he, as President, did not have the powers Smith wanted to exercise, a fact of which Davis was made constantly aware by newspaper editors, Confederate Congressmen, and state governors who enveloped him.

Smith’s forces were desperately short of war material (ammunition, firearms, gun powder, pack animals, cannon, shot and shell, uniforms, boots for the men and shoes for the horses) but most of he was short of men. Periodically he would launch an enlistment campaign offering such inducements as he could (immediate furlough and an enlistment bounty in worthless Confederate dollars). Desertion was astronomical, one division reported 300 men fit for duty and 4,500 absent without leave. To stop that he would take troops from contact with the enemy and set them to find deserters who would then be shot on the spot as a lesson to others. This was hardly an appealing duty and members of those patrols often themselves deserted. It was a downward spiral.

The best way to avoid conscription was to enrol in the state militia (which remained true during the Vietnam War; think George W. Bush). The state militias’ registers were bursting with names and for each name there was an exemption. None of the states had the capacity to arm these militiamen with any more than the farm shotguns they brought with them. Few states had officers who could drill and discipline them, and since the officers were elected (per the state constitutions), any officer who tried too hard was defrocked. Moreover, a state militia cannot go outside the state (again by the state constitution), limiting cooperation with others to nearly nothing. While Smith’s armies regularly opposed forces four or five times larger, vast numbers of able bodied men of soldierly age had their exemptions, and these very same men urged Smith to fight to defend their homes and property (slaves) from the Yankee scourge. It did not take long for this circle of irresponsibility to wear out Smith’s good humour. With no legal or political authority but the weapons of his press-gangs, he forced militiamen into the ranks. Of course some of them deserted and sicced governors and newspaper editors on to him, and a host of trial lawyers brought endless suits. He persisted with some success.

To pay his army, to pay civilians for their labor as teamsters or ditch diggers, to buy uniforms, ammunition, and everything else he need a source of such goods and he needed money. The source was obvious. Look at the map above. México! There were plenty of Méxican entrepreneurs to supply whatever was needed. Then the problem was the Readies to pay for it. The only resource of value he had at hand, and he had at hand plenty of that, was cotton. In warehouses, on farms, in sheds there were hundreds and thousands of bales which had built up when the Union occupation of New Orleans stopped the trade through that port. Those who owned the cotton would not, however, sell it for Confederate dollars. Smith tried bonds; he tried his own warrants; he offered interest on the Confederate dollars – no sale!

What was a general to do?

He seized it. In some operations 60,000 bales were impressed by his troops in one day. ‘Impressment’ is the fancy word for stealing with a gun in return for a chit of paper. Get this in perspective, the price of cotton on the world market was very high. One or two bales would be worth a fortune to a private solider. Yes, there was private enterprise among the ranks and not all the cotton seized entered the lists on Smith’s accounts. Even so, in one calendar year he sold cotton for $30,000,000 gold dollars in México. By the way, there is no evidence, none, that Smith enriched himself in this trade.

Cotton bales

Cotton bales

He started shipping cotton to México under armed escorts (yes, some owners formed posses and came after their crop) and he was in business. He created a Confederate Cotton Office and this bureaucracy identified, compensated (seized) crops, stored, shipped, and sold it. To do so it acquired (seized) wagons, mules, harnesses, reins, and teamsters (who were conscripted on the spot). States’ rights, habeas corpus, private property did not figure in the equations. His assertion of authority went beyond even presidential powers.

In addition, to keep the wheels turning on this enterprise much was needed, wagons, wheels, tackle, yokes, horse shoes …. Smith set up foundries and factories to manufacture all this. Soon there was a Confederate Army tannery turning out leather for harnesses, an ore and refining foundry for horse shoes…. To manage these affairs an Office of Army Supply was created that socialised all of these works. There were many objections, and law suits were spun, letters of complaint slowly found their way to President Davis’s desk in Richmond, and he would in turn chide Smith in a letter received eight months later. On the rare occasions when Smith received an explicit and direct order from Davis to cease an activity, he obeyed exactly.

In short order French armament corporations started swapping cannons for cotton along the Rio Grande. There was an increasing French military presence in México at the time and many French field officers found they had rifles, saddles, horses surplus to requirements which they swapped for cotton. The entrepreneurial spirt blossomed.

While England and France had limited sources of cotton in their empires, the mills of New England had ground to a halt for the want of cotton. Sure enough purchasing agents from New England were soon buying Trans-Mississippi cotton along the Méxican border. That is, they did not buy it but swapped it for Colt revolvers, ammunition, Remington rifles, steel knives, cassons, harnesses, heavy serge uniforms in grey which they brought with them from New England. That is right. In fact prior to the closure of New Orleans many of these … businessmen had been doing this since 1861, and they were merely relocating the trade in 1863 to the Rio Grande.

One result of this trade with New England was that the Confederate troops in the Trans-Mississippi were often armed with the latest weapons, just as the their Union counterparts received them, too. A shipment of 10,000 repeating rifles to New Orleans would be split, 5000 to stay and the other 5000 shipped on to México and Smith’s procurement bureau. Then when a Union cavalry patrol armed with Remingtons went out to blast Rebels, they quickly discovered the Rebels had the same rifles, and blasted back.

Since Napoléon the French had been leaders in artillery. The French sold cannons to Smith’s agents. Accordingly, Smith’s troops had better, though fewer, cannons than the Union forces they encountered. Better in that they were more accurate and easier to re-load.

To manage relations with México, France, Britain, and the New England traders Smith created his own State Department which negotiated agreements, exchanged agents, and so on. Everything was in writing. He made treaties with both Méxican and French authorities to pacify the border for this trade. Not only was he trading with foreign countries, he was trading with the enemy.

Nonetheless, his command often suffered privations because making or buying the material was one thing, distributing it over the vast reaches of the Trans-Mississippi with its few railways, many fordless rivers, its animal-track roads, disrupted raids by Federal cavalry was hard.

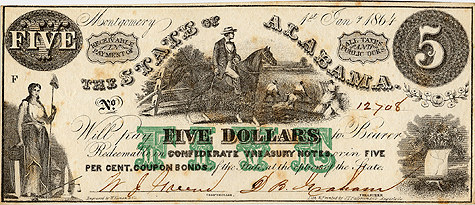

Cotton iconography features on nearly every Confederate bank note to remind the world of the white gold. On this five dollar note the overseer sits atop a horse with a whip in hand, ready to increase efficiency by using it on the blacks picking the cotton. All the while Lady Liberty on the lower left serenely observes. Most Confederate currency portrays blacks, too, always busy and happy at their work.

A good part of the book is taken up with accounts of military manoeuvres, battles, campaigns which make appalling reading. The size of the forces involved are microscopic compared to either the Virginia or Tennessee theatres but the death, the cold endured without shoes, the dying, the amputations, the disease, the swarms of stinging and biting insects, the gangrene, being constantly wet in the bayous, the malnutrition, the blinding heat, the field of rotting dead men are just as real.

The governors of each of the states and territories wanted Smith to defend every foot of their jurisdiction, the more so when the Union occupied most of a state. Missouri had to be defended, then recovered. Arkansas. Louisiana. Missions impossible, those. The Union picked and poked around looking for easy opportunities using the control of rivers to roam far and wide, supplemented by large bodies of cavalry riding on well-fed horses.

New Mexico and Arizona were the route to California gold and very early in 1861 Confederate expeditions went through Death Valley toward that El Dorado. Nature – it is called Death Valley for a reason – hostile Indians, and some Union army posts were enough to stop that. Even so there was a Confederate governor-in-exile and in the Confederate House of Representatives in Richmond sat a delegate from the Confederate Arizona Territory. Kansas figured as a continuation of the Jayhawk War and a refuge for raiders into Missouri, including the infamous William Quantrill (1837-1865), Jesse James (1847-1882), and other thugs later made into celluloid heroes. Slaughtering defenceless civilians was the preferred vocations of these men, e.g. Lawrence Kansas, not encounters with Union army patrols. There was also at least one raid into Colorado.

The Indian Territory (Oklahoma) was home to Cherokee Indians, regarded as the most civilised savages for they had adopted many of the white man’s ways: clothing, newspapers, slavery, and political representation. They negotiated an alliance with Kirby Smith against promises of future autonomy, i.e., no state of Oklahoma.

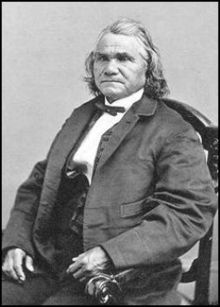

Apart from the shreds of papers affirming this alliance, it was embodied in a brigade of cavalry consisting of Cherokee and Creek Indians led by Brigadier General Stand Watie (1806-1871) himself a Cherokee, which remained loyal to the Confederate cause through thin, thinner, and thinnnest.

Stand Watie, Brigadier General C.S.A.

Stand Watie, Brigadier General C.S.A.

It operated independently, and mostly in today’s Oklahoma and disrupted Union communication and transportation, and occasionally joined one of Smith’s armies for a combined operation like the invasion of Missouri and then Arkansas. This brigade was one of the most reliable in Smith’s command.

While Texas was not often a scene of combat, when it was General John Magruder showed once again his tactical acumen and held off the threats made, including some French sabre rattling from México which Magruder saw-off in short order. In Arkansas General Richard Taylor did the bulk of the fighting in the Trans-Mississippi with the little wherewithal Smith could supply. He, too, had a tactical mastery that allowed him to overcome the odds often, but not always. On the debit side Generals Theophilus Holmes and Sterling Price made a mess of anything they turned their hands to, and Smith’s efforts to promote them to some harmless station, preferably in Cis-Mississippi, did not secure the support of President Davis, until it was too late.

By March 1865 a means of regular, albeit hazardous, communication had been established between Richmond and Smith at Shreveport. While the Confederacy was crumbling, the Confederate War Department launched an inquiry into the staffing Smith’s command. There were too many generals on the payroll! (Never mind that none of them, nor anyone else, had been paid in sixteen (16) months and then only in worthless Confederate dollars.) In an exchange of letters Smith was required to account for his every general and his duties in detail. Considering the vast distances within his command, he was not over-generaled, but try convincing the paymaster of that by letter.

So does the tail wag the dog.

Ever the dutiful soldier, he prepared the report but in the end he did not submit it. Why not? Because the War Department ceased to exist a fortnight later. Love it? The ship of the Confederacy is sinking, water is everywhere, and the head of payroll division sits grimly at his desk as the ship goes down demanding an explanation for those damn paper clips in the Trans-MIssissippi! It is the principle that is at stake!

As news of the surrender of Lee and then Johnston was broadcast in the Trans-Mississippi the scattered remnants of Smith’s garrisons, independent brigades, and armies evaporated. In some cases the local commander went to the Union line to surrender with some formality, but in most cases the Johnny Rebs walked away into the night. Smith surrendered formally at Galveston, and then took himself and his family off to México, because by that time, Lincoln had been murdered and the future was dark. He returned in late 1865.

He became a professor of botany and taught at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee for almost thirty years.

Conclusions? The author draws five conclusions from the study, and they make all the detail fall into place very nicely. However, I do wish they had been outlined at the start so I could have borne them in mind as I read.

1.The Confederacy conceived of the Mississippi River as a boundary, not a highway. Dividing commands at that boundary split forces that would have been better combined as the Federals proved repeatedly along the Father of Waters. This was the major strategic error. This decision divided command at the River, and then required explicit orders from Richmond for any cooperation across the River by Confederate forces on the two sides. More often than not, Richmond could not decide at such a distance what to do, and even if a decision was made, the communication was very poor. I trace this reasoning back to the general conception of military departments (matching state boundaries) which in turn paid court to states’ rights in the Confederacy.

2.Despite the hardships, the Trans-Mississippi Department sustained itself agriculturally and economically. It supplied the army with the necessities and civilian life went on. Though worn down and worn out it went on. The major problem was not production of the necessities of life, it was rather the distribution on the primitive roads, a problem compounded when the Mississippi River was closed.

3. Spared the extensive damage of general warfare experienced in Tennessee, Georgia, and Virginia, its armies never suffered a decisive defeat, yet the Trans-Mississippi did suffer a collapse of morale which was apparent in 1864, well before Lee’s surrender. That surrender was the the end of this collapse not the beginning. Kerby’s evidence for this collapse is ingenious.

4.Contrary to the conventional thesis that the ideology of states’ rights defeated the Confederacy from within, in the Trans-Mississippi General Smith worked effectively with the state governments in most ways, most of the time. Certainly, there was no Georgia in the Trans-MIssissippi, Georgia being the state that – some say – did more to defeat the Confederacy of which it was part then any other factor, except possibly South Carolina!

5.In the Trans-Mississippi the erosion of morale (see 3 above) that culminated with Lee’s surrender started very early in 1862. The initial cause was not defeat on the battlefield anywhere but the mobilisation of men and economy for war through conscription and impressment. Though everyone bore it, it sapped energy, enthusiasm, and spirit. Subsequent defeats sped the erosion but did not start it. Not sure what to make of this one. Again Kerby finds evidence, over looked by others, to sustain this thesis.

Robert Kerby

Skip to content