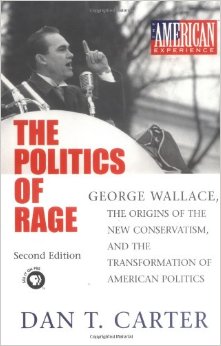

Three men publicly declared their intentions to run the first time for public office within hours of each other, one in Massachusetts, another in California, and the last in Alabama: John Kennedy, Richard Nixon, and George Wallace (1919-1998), and despite his four presidential campaigns the latter, Wallace, has all but disappeared from the popular consciousness. The evidence is celebrations of anniversaries reported to television and the shelves of bookstores. Kennedy and Nixon appear now and again in those places. Pigmies (journalists) till occasionally try to hack a byline out of Kennedy or Nixon. Scholars continue to evaluate their achievements in monographs. The fiftieth anniversary of this or that has commanded television time. Hits on the internet are millions for Kennedy and Nixon.

But George Wallace, though in the time he preoccupied both Kennedy and Nixon, and commanded headlines around the world, is now all but forgotten except to specialists in American regional politics. Moreover, later in life, outwardly Wallace executed a 180 degree turn in his public persona and went from a fire-eater to a grand old man. Who was George C. Wallace?

He was the oldest son in a comfortable family, though its fortunes had declined in the previous generation, along with millions of others when the Great Depression hit. George completed high school and graduated from the University of Alabama with the help of the G.I. Bill of the (later despised) federal government.

He was small, and often called ‘Little George’ rather than ‘George, Junior. ‘ If that irritated him, he found an outlet for any resentment in Golden Gloves boxing. He did well in that as a bantam weight. More than once knocking out an opponent. As one coach said, George did not want to win the fight, he wanted to hurt his opponent. Trying to teach him to score points for a technical victory had no effect. George did not want to score points, he wanted to deck his opponent, draw blood, and have KO recorded. The pugnacity he showed later was there from the beginning.

He had served in the United State Air Force in the Pacific War and flew nine missions in a B-29 over Japan. He was the flight engineer for the large and complicated airplane. While the Japanese defences were weak sometimes it only took one hit to bring down even one of these super fortresses. In addition, the distances, the weather, the fatigue of the crew on 16-hour flights in combat conditions, and the temperamental nature of the aircraft combined to produce 5% losses on every sortie; if 500 planes took off for a mission, 475 made it back. Each plane carried 11-crewmen and so that meant 275 deaths. Yes, deaths because when the planes went down, whether over Japan or open water, all hands were lost. Air-sea rescue existed but the vast expanse of the Pacific ocean over a 6,000 mile course made recovery a million-to-one shot.

On at least one flight Wallace’s handling of the engines, the fuel flow, the oil pressure, the hydraulics saved the plane from disaster. Later he secured an honourable discharge despite some dubious behaviour. (From the details in these pages I rather think he served in the same unit as my father, likewise from the South, but there the similarity ends.)

When the war started Wallace knew he had to serve in order to secure his future political ambitions. And he had political ambitions that were articulated from about 15 years of age. He earned a place as an intern in the Alabama legislature and declared that one day he would be governor. Many a boy and today many a girl has done something like this. Few of them, however, conducted the kind of campaign he did to secure that internship. In early summer when school was out his father drove him to the capital, Montgomery, and young George laid siege to the legislature like Grant before Richmond. He had already written a stream of letters to every member of the legislature explaining his exceptional merits for one of the very few internships available, pledging to serve above and beyond the call of duty. Once in Montgomery he presented himself at the door of one legislator after another and talked his way into most. He slept at least one night in park and gave his suit an undergraduate iron, i.e., he slept on it. His father left him to his own devices. For the first but not the last time, Wallace wore down his adversaries and he got an internship. He loved it, and did do twice the work any of the others.

The man was something of a loner despite coming from a family of five children. He could keep to himself for days at a time, as he often did during this internship and later in the Air Force, but if he was with other people he was garrulous, excited, nervous, twitching with energy, and talking, and talking, and talking nothing but politics as one contemporary after another says, though what politics he talked from fifteen onward is not clear.

What is clear is that he had a burning ambition and politics was the field. The two defining poles of Southern politics were (1) hatred of the North (Federal) government because of the Civil War and Reconstruction and (2) white superiority at the cost of black oppression. The former meant that the federal government was the real enemy, though the largess from FDR’s many programs was quickly pocketed in the South, it was nothing more than overdue compensation for the great evils the North had visited on the South. Suitably encoded for contemporary sensibilities, we hear the same motifs today from the Tea Party and its media service, Fox News.

Leaving aside the details, which are thoroughly documented and dramatically presented in this book, from the beginning Wallace was a hollow man.

Wallace had a gigantic need for recognition which translated into an unquenchable ambition for political office (even before taking the oath of office as governor the first time he referred to running for president ‘next year’) that combined with his belligerent temperament. To serve that ambition he would cheat, steal, and lie while denying everything. His defiance of the federal government on civil rights was – it is abundantly clear – contrived to lock-in the white vote for his ambitions. He had no interest in the constitutional or legal aspects of the dispute. Nor did he seem to have any personal animosity to blacks. As Hitler never personally harmed a Jew, so Wallace never harmed a black person. Racism was necessary to win and he would not be out done in that. No sir! If racism got votes, he would talk racism day-and-night. Against such singleminded determination, the federal government wobbled. The Kennedy Administration wanted compromise not confrontation but Wallace wanted confrontation (before the television cameras) and not compromise of even the most cosmetic kind.

Wallace promoted the mayhem of Selma and the maelstrom of Birmingham. The descriptions of the bomb, the razor, poison, the truncheon, C-4 teargas (which is toxic), the torch, the shotgun, the knife, the pistol, the high-pressure firehose that broke limbs, the baseball bat, and the snarling police dogs, and let us not forget the electric cattle prods were, as one French journalist said, worse than any he had ever seen in banana republics. Wallace was indifferent to the blood he had let, ever ready to blame someone else. His message was clearly understood by those whites who wanted to fight. The haters came out in force and Wallace privately invited the Ku Klux Klan to mobilise to the drive the blacks off the streets.

George Wallace. ‘Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! Segregation forever!’

George Wallace. ‘Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! Segregation forever!’

Before reaching for stereotypes about Alabama, it might be noted that in the 1920s a governor of this very same state, Oscar Underwood (1862-1929), sacrificed his political career, including his own presidential ambitions, to confront the Klan. Equally, Wallace’s immediate predecessor in the gubernatorial chair, Jim Folsom was an advocate, albeit inconsistently, of racial accommodation. Wallace’s constituency was always a minority but it was an intense minority that he had identified, legitimated, recruited, mobilised, and unleashed with the full support of the state government and the connivance of some of Alabama’s Washington representatives and senators. I said ‘recruited’ because there is evidence that some of the perpetrators had flocked to Alabama from other states to seize the opportunity to crack skulls.

Wallace had found, as did another Southern midget, Alexander Stephens (1812-1883), that crowds were bored when he talked about states’ rights but responsive when he went in for race-baiting. What was am ambitious man to do, but play the race card? It was the only card in the deck.

Having just read some of the Robert Penn Warren’s essays written at the same time as Wallace was at his pinnacle it is hard to believe these two Southerners came from the same planet.

While Wallace ranted and raved at the evils of the federal government, he continued to receive and bank his monthly check for his war wound. War wound? His discharge was based on his unfitness for further duty due to mental instability, i.e. combat fatigue. For that disability he received a part-pension for the rest of his life. Imagine what an opponent as unscrupulous as Wallace himself would have made of that fact.

Wallace had a retentive memory and he made a point of remembering people he met, because they might be useful later, but he had no rapport with them, unlike Huey Long. They were assets to be catalogued not people whom he could help. Long’s faults are encyclopaedic but he never played the race card. There is a coldness at Wallace’s core, which is also evident in this relationship with women, including his ever loyal wife, Lurleen. So seldom did he see his children that she wondered if he would recognise them in a crowd.

In all he served three discontinuous four-year terms as governor, and his wife, Lurleen, served one four-year term as his surrogate. As to Wallace’s change of heart after his own ordeal, the author is sceptical. Wallace’s injuries were terrible and left him in constant pain. But after so many years and so many lies, perhaps the one person who believed his lies was George Wallace. The author gives very short shrift to this period in Wallace’s life which I took to be a silent comment on Wallace’s credibility.

Reading this book brought back those times to me, and it was disturbing to recall those days of the news each night of blowing up children in churches, burning to death families at the kitchen dinner table, the murder of university students in the street, a woman beaten to death with baseball bats by five men in a town square.… Worse, the culprits in many cases were well known, and some openly bragged of their deeds, others were on-duty police officers. Looking back, it beggars belief. I had no wish to see ‘Selma.’ The original was enough for me.

The author goes to remarkable lengths to be even-handed and let the facts speak for themselves. They do.

Dan Carter

Dan Carter

Presidential campaigns. Wallace’s strategy was to produce an indecisive election, i.e. no candidate with majority of electoral votes, and throw the (s)election of the president into the House of Representatives as prescribed by the Constitution at the time. There a combination of Southerners with some Northerners from blue-collar constituencies might give him enough votes to wangle a Vice-Presidential selection, and from that base the next time he would be the leading contender for the top job. It is not as crazy as it sounds.

1964. Wallace entered and campaigned hard in three Democratic primaries, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Maryland, and did well. That ended the supposition he was a regional politician with no appeal outside the deep South. After dropping out, privately he offered his support to Barry Goldwater in return for the Vice-Presidential place on the Republican ticket. Goldwater declined. LBJ swept all before him.

1968. Wallace ran as a third party candidate with Curtis ‘Bomber’ LeMay. Richard Nixon won but he feared that Wallace would split his vote. Once again Wallace let it be known he would accept the Vice-Presidential slot on first the Democratic and the Republican ticket. This messages were ignored. He got ten million votes, carried five deep South states with forty-five Electoral votes. This was his high tide. He seems to have taken votes from blue collar workers in the North who might have otherwise voted for Hubert Humphrey and from Southern rednecks who might otherwise have voted for Nixon.

1972. Wallace entered the crowded Democratic primary field and won Maryland, Michigan, as well as Florida. Once again he approached Hubert Humphrey through an intermediary about the Vice-Presidential slot and once again Humphrey did not respond. While Wallace got votes, George McGovern’s campaign was more astute at getting delegates, and there was never a chance Wallace could win, but he could certainly be a spoiler. Nixon was delighted to see him in the Democrat chicken coop but worried he might bolt once again and run as a third party candidate. Many calculation were made. Among McGovern’s campaign staff were Bill and Hilary Clinton. Then that weirdo shot him. HIs assailant sought fame and barely knew who Wallace was. One weirdo too many.

1976. In a wheel chair he entered another crowded Democratic primary field but had little impact and dropped out quickly. He was allowed to address the convention, but he was a shadow of the rabble rouser he once was, and his effort to play the elder statesman was lame. Jimmie ‘Who’ Carter won and won again, the nomination and the election.

Footnotes to Wallace

Hatred and fear, these win elections. This was the lesson the Republican Party took away from the Wallace experience it has gradually make its own since. To paraphrase a Republican campaign analyst in 1968, find out what they fear, find out what they hate, and play to those and only to those. If white blue-collar workers fear that lower-paid blacks will take their jobs, play that card. If white middle-class suburbanites fear blacks will move into the neighbourhood and lower real estate values and mix races, play that card. ‘Playing the card’ means articulating these fears for them in a way that is socially acceptable but unmistakeable — code it — so that they can say it and in so doing realise they are not alone. This crystallised into ‘The Silent Majority’ which was hardly silent and probably not a majority, but it was a brilliant conceptualization. People motivated by hatred and fear will go to the polls and vote. Wallace’s campaigns both in Alabama and in northern primaries brought many hundreds of thousands first-time voters to the polls in general or primary elections. That campaign manager used other examples and expressed them much more forcefully than I have done in deference to the PG-17 rating of this blog.

Demeaning accounts in press. The resentment that Wallace bore toward the North and its surrogate, the federal government, is easy enough to understand when reading the contemporary press accounts of him, his followers, and his campaigns quoted here. The ‘New York Times,’ ‘Time Magazine,’ CBC-TV News, all struggled to find a slot into which to place them, and they settled on the easiest one to hand. Drawing on their knowledge of the South from reading Al Capp’s ‘Lil Abner’, the pigmies of the Fourth Estate labelled them hillbillies, rednecks, hicks, yokels, and rubes. The early descriptions of Wallace on the campaign trail in North reek of condescension and deprecation. Everything about him was described as though he were a specimen in a jar, his wristwatch, his haircut, his finger nails, these were all subjected to the journalistic acid test, namely, can I get a byline out of this?

Skip to content