William Butler Yeats wrote that ‘life is a long preparation for something that never happens.’ No, he was not thinking of the Chicago Cubs in a World Series, but it fits.

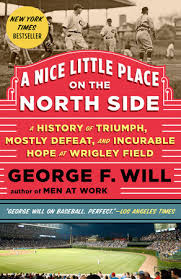

I omitted the subtitle: ‘History, Triumph, Mostly Defeat, and Incurable Hope at Wrigley Field.’

George Will has long been an expositor of baseball, well before Ken Burns discovered it. This book is an ode, spiced with some gritty reality, to Wrigley Field and those who have graced and disgraced it from zealous fans, first-ball throwing presidents, class and déclassé players, managers, and owners including the fabled P. K. Wrigley, famous for his indifference to baseball and his genius for marketing.

All of the lore is here reiterated: Babe Ruth calling the shot, Hack Wilson the perpetually hungover human fireplug, the storied Tinkers-Evers-Chance, smiling FDR throwing out the first ball, Ruth Ann Steinhagen shooting first baseman Eddie Waitkus (who had never met her before she pulled the trigger on him), Wrigley’s many innovations from Ladies’ Day to the ivy on the walls, and his decision to contribute the steel for light poles in 1941 to the war effort and the resulting, accidental, consecration of Wrigley Field as a cathedral to daytime baseball. Waitkus, by the way, was the inspiration for Bernard Malamud’s novel ‘The Natural,’ ironic since Malamud had no interest in baseball, nor any knowledge of it either, as is apparent in the novel, somewhat emended by the screenwriter for the movie of the same name.

Did the Babe really call his shot? The record is far from clear, but the legend is indelible. Tinkers-Evers-Chance turned very few double plays but the journalist who said they did, created a reality that has endured despite the wizardry of sabermetrics. Will is very good at presenting a lot of facts, including statistical data, in digestible portions with spritely commentary, including the paltry number of double-plays this trio made in the year when they together ascended to myth.

Hack Wilson was certainly hungover on days when he blasted home runs. His drinking shortened his career and life dramatically. FDR and Chicago Mayor Anton Joseph (Tony) Cermak made an odd couple on opening day in 1933, and even more so a few weeks later in Miami when Cermak was murdered at FDR’s side, the speculation being that Cermak was the target of the Mafia as a warning to FDR to call off the IRS or to leave Prohibition alone, which had made them millionaires.

The end of live-ball era is much discussed, surprisingly, without much enlightenment. The rather mystical implication is that the live-ball ended with the advent of Great Depression. One catastrophe begat the other. Members of the pitching fraternity did not mourn the end of the live-ball era and celebrated the dead-ball era. I speak as a brother of this lodge.

The Olympian RBI totals Wilson and others compiled in the live-ball era endure, unlike most other records from the days of yore. Why is that? In those days most teams had but one big hitter who was preceded by yeomen who hit singles and were thus on base for the clean-up man. In those days before money-ball, pitchers threw strikes to such clean-up hitters and the RBIs followed. In subsequent years most teams have more, better hitters so there are just fewer ducks-on-the-pond when the sluggers pounds another home run. And pitchers are often instructed not to pitch to the big hitter when there are runners on base, even to the point of walking in runs. Sammy Sosa and Mark McGwire hit phenomenal numbers of chemically-assisted home runs without threatening the RBI record.

Denizens of Wrigley Field have included the great and the good, the ordinary and the unknown, and the bad and the ugly. In the heyday of the aforementioned Prohibition Al Capone was a regular. Later Jack Ruby sold peanuts there before finding his way to a Dallas basement carpark a generation later. Ray Kroc had his first experiences at retail food in the concessions under the grandstand. And of course those indefatigable entrepreneurs the Bill Veecks (as in wreck, they always said) Senior and Junior.

While the leagues expanded and new stadia were built Wrigley Field, together with Fenway Park, remained testaments to the past. These new stadia seated tens of thousands, and came equipped with all mod cons, as the realtors say, from plasma television screens to beer on tap, cushioned seating, hot and cold running distractions, and more. They occupied vast tracts of land, sometimes seventy acres far out of town; the further out they went, the more parking they needed for fans to drive cars there; the more parking they needed; the further out they went. Some went so far out they no longer have a connection to any city like Foxboro in Massachusetts.

The needs of television to fill airtime and the need of the owners to sell fans more than a ticket once there, and the needs of fans to do more after driving hours to get there and back turned many such stadia into entertainment complexes. The distractions are many. One of the worst, and there are many contenders, are sound system that assault the senses, though thankfully being largely open spaces, never as excruciating as at NBA games. Being more expensive than the Apollo space program, these colossi have to multi-task, and this was integrated into their design: baseball, football, rock concerts, soccer, you-name-it, anything and everything.

The predictable result was that they do not suit any of them, least of all baseball, which is best played on Astro-dirt.

Wrigley Field stood apart from this pursuit of Baal for a generation or more, literally held together by chewing gum in more than one way. However, the balance sheet caught-up one day. Lights came. There followed a scoreboard that can be read by Apollo astronauts on the way to the moon.

Will deftly demonstrates that the fortunes of the Chicago Cubs who play (at) baseball in Wrigley Field are less important to fans than the price of beer. That price predicts attendance better than the team’s winning percentage (which the cognoscenti know seldom tops .500). The Cubs team has long been the lesser interest both to the ownership, the management, and the fans than the beer.

Will discreetly leaves the players out of this list those indifferent to the game itself. Though some of them did not evince much interest in the game while playing at it what with two errors by the same outfielder on one play in several games, six walks and a balk by a pitcher in one inning without a single out, ground balls lost in the sun, outfielders charging balls hit over their heads, one batter called out on strikes without a swing of the bat a record number of consecutive times, infielders unaware of the location of the ground when it came to ground balls, players traded…for themselves with a cash refund. All of which makes the achievements of some individuals all the more remarkable, like Mr. Cub, Ernie Banks, Bill ‘Sweet’ William(s), Ferguson Jenkins, Ryne Sandberg, Kerry Wood, and a few others.

The book ends with a coda from that poet of baseball Bart Giamatti, he who banned one of its greatest players (for not playing by the rules), who chided us to remember that it is just a game and that is why it is so transcendent, for two hours outside the river of time.

As the story draws to a close the team has changed hands several times and the unforgiving business of major sports prevails, though others have learned some of the lessons of Wrigleyville, as the neighbourhood calls itself, and some new stadia are more like Wrigley Field these days than Chavez Ravine (that is a memory test).

George Will

George Will

When I ordered the book I did so in the recollection that George Will is a wordsmith of excellence, and that assumption was amply vindicated by the light touch, the glib segues, the pertinent metaphors, and the economical allusions. Altogether a perfect game of a book. I read it in one sitting. Gulping it down.

Skip to content