An irreligious and illegitimate, left-handed vegetarian homosexual pacifist with one name and a shock of flaming red hair who dressed as dandy, seldom finished a job, and never published, that is Leonardo from Vinci (1452–1519). He would be banned by the NRA in Alabama, hung by the Veep, and not get a job at a university today.

Never hit a KPI. No tenure. No promotion. Try imagining his 360-degree review. Go on, try!

He was the illegitimate son of a notary and a servant girl. His father recognised and accepted him though for the first twelve years or so he was brought up by his mother, the servant girl, and her new husband. At about twelve Leonardo went to live in his father’s home. There is no doubt the first eleven years were formative. Read on.

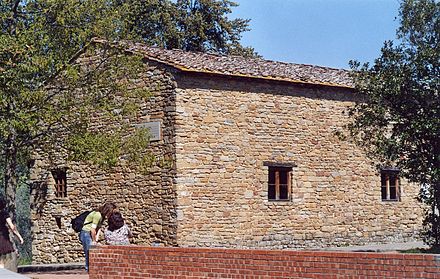

His father’s house.

His father’s house.

While in the care of his mother he was free to roam unshackled by the conventions of the notary’s higher social status and rigidly conventional family life. Roam he did through hills and dales where he began the close observation of nature that never stopped. Like the boy who became Peter the Great, he was free of the inhibitions of the status that he later acquired.

His father soon realised that this boy was never going to be a notary. He was dreamy, always scratchy away at things, doodling in the dust, pulling things apart. His father arranged to apprentice him to an artist’s workshop in nearby Firenze. It was hog heaven for the lad. He did the work assigned to him, starting with crushing shells to make paint, cleaning brushes, and sweeping floors. Then he went on to preparing the surface of boards, walls, and canvases for paint. He worked his way up from these entry jobs, very quickly, to painting backgrounds like sky and hills. Next he was painting background figures which soon got him promoted to foreground figures. While a teenager his talents surpassed the master of the workshop.

Leo stayed an apprentice for longer than usual because he was content, but eventually his father staked him to set up his own workshop, and perhaps assisted in getting some early commissions for him. Leo’s talents bloomed. His only ambition was to keep puzzling away at things.

He took commissions and worked on them, in some cases for years, without finishing many of them. As he did so, he invented new techniques, the most significant being oil painting, which in turn led to his famous technique of sfumato. Together these two measures allowed him to produce colours and dimensions unlike anything previously done in tempura. Later he would stress the goal of creating the illusion of three dimensions on two. As did Ludwig von Beethoven, so Leonardo invented form and content together.

Living in bustling Firenze, Leo extended his close observation to people. He begun to carry a small notebook night and day and he sketched endlessly, as he observed. He also wrote notes and puzzles. About 7,200 half-quarto pages from these notebooks have survived that is, perhaps, a mere portion of the original total. Still this is more on paper than a contemporary biographer of Steve Jobs could find because Jobs worked in digital media from the get-go and most of it has disappeared with the passing of floppy discs, hard discs, and web sites.

Instead of finishing a commission, Leonardo would spend hours examining the condensation on a glass of cold water on a hot day, ants on a leaf, the faces of men in a pub, or applying the eighteenth coat of oil paint to a tree in the background of a painting. While he concentrated hard on what he did, he did not focus on completing tasks. All trip, no arrival.

The anonymous accusation was a common practice of the time and much emphasised in Firenze. Write out an accusation and drop in the box. Done. (This was a practice revived by the Naziis in Occupied France.) These accusations covered everything from tax dodging, to cheating business partners or customers, short changing deliveries, adultery, and homosexuality. While sodomy was a moral sin and a capital crime, it was also much practised in Firenze. Hypocrisy is not confined to D.C.

One such latter accusation was made against Leo but it was unsubstantiated upon investigation and he saw it off. Other similar accusations, however, followed. Whether any specifics in the assertions were so, it is true that he preferred boys to girls or women. True or not, sustained or not, the accusations and innuendoes were making his life and work difficult. After he left Florence, nothing more is heard of such accusations, though it is clear that was his way of life.

In Milan the usurper Il Moro, was buying legitimacy by attracting entertainers like Sharon Stone to Milan. To make peace with the new ruler of Milan, the Signoria of Firenze commissioned Leo to make a lyre of silver for Il Moro and personally to deliver it. While so doing, Leo also applied for a job as engineer, maestro, painter, and celebrity pet. The duke commissioned him to do a giant equestrian statue which of course remained unfinished during the seventeen years Leo spent on Moro’s dime.

He did earn his keep by producing entertainments for the duke. These shows included automatons, flying hoists, tableaux, and all manner of smoke and mirrors. The author makes the point that with these shows, Leo had to deliver on time, on target, and on budget. And he did! Repeatedly.

Being an impresario distracted him from the equestrian bronze but made a great reputation for the duke. (Later this duke would invite the French to come to his aid and that precipitated more than thirty years of incessant war in the Italian peninsula. The French liked shopping in Italy, and paid with swords, crossbows, siege guns, cavalry, and more.)

In these shows Leo’s engineering and artistry were united. They also demonstrated his management ability to prepare and stage them. He spent years in Milan and only left when Il Moro’s world collapsed. He returned to Florence briefly and then in a dream come true King Francis I of France offered him a pension, not a commission for a specific work or works, but retainer to do what he liked.

He set up a house and pottered away.

While he had been a strapping red head in his prime, he aged rapidly and badly. Those who met him for the first time in his fifties and later routinely took him to be ten or more years older than he was.

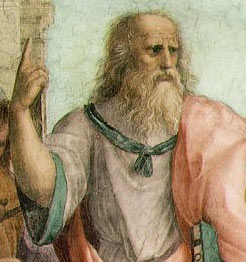

There is some reason to believe that Raphael used him as the model for Plato, as above, in his great painting of the Academy for a Pope.

Most of Leonardo’s engineering ideas were never tried, and he completed few paintings, yet he was recognised far and wide as the genius of the age. How does he compare to Paris Hilton, that is a question to consider. His recognition infuriated toiling rivals like the religious zealot Michaelangelo who tried to blacken Leo’s name at any opportunity.

To commission a work from Leonardo was difficult and almost always fruitless. He often played hard to get and declined commissions. When he accepted, whatever the notarised contact said, it was done in his way and on his terms. That most famous of all paintings, the Mona Lisa, which the author details at length was never finished. While Signor Giaconda commissioned it, he never saw the completed work. Instead like several other paintings Leo carted it from Milan, to Florence, to Rome, to France, daubing at it off and on for years.

It was not procrastination. His technique took time. In Lisa’s case, the canvas had a base of white lead, which even with other coats of paint over it still reflects light like nothing else. The lead coating took time, and by the way, this unique property of white lead paint was recognised by others and commonly used on the eyes of portraits. An artist who licked his brush to get a point with this lead for the white of eye developed lead poisoning and this killed many.

Over the white lead Leonardo added very thin coat of oil paint and then waited weeks or months for it to dry. Then another with a wait. And so on. At times he changed his mind and altered a painting and waited. He out waited all of his patrons except Francis who had hired him as a companion more than anything else and they seemed to enjoy each others company. When Francis had time off from murdering Protestants or sacking Italy, he visited Leo for a natter. Though I did wonder, without enlightenment, what language they spoke together.

Leonardo was never idle and in the weeks of waiting for paint to dry he would take up a new project and do, say, a series of drawings of water falls, or rivers. He was always fascinated by the motion of water. Indeed at times he speculated that water to the Earth was as blood to the body, and he meant that literally as much as figuratively. Though for all his polymath genius he never understood the fifth grade science of evaporation.

While he learned much from reading, he never published his own research, though he spoke of doing so, but those words became another unfinished project. He had been an autodidact in his early years and had so little education he could barely read, and he was defensive about that for years. More or less secretly he spent years trying, off and on, to learn Latin with little success. (Miss Vera Earl, MA, would have put his declension in order in no time!) Gradually he came to read Italian and learned from the tomes he read. Perhaps there was a psychological barrier to publishing because of his early life in which books were for others.

It is a wonder, in an age without knowledge of germs, he lived as long as he did. That the white lead did not kill him may be down to his slow pace of painting. But also, where local circumstances were conducive, he did hundreds of autopsies with accompanying drawings of the muscles and bones of the human body without much hand washing, sterilising of knives, and such. Since most of the cadavers he could work on came from the poorest strata of society, often they were diseased and infested, yet he lived.

This quintessential embodiment of the Italian Renaissance, this son of Firenze, this Tuscan-speaking Italian died in France and King Francis gathered his mortal possessions, so that in time the Mona Lisa and many of the drawings passed to the Louvre, where I once saw Lisa behind a bullet proof glass and over the heads of and in the storm of flash bulbs from hundreds of Japanese tourists. I also saw for a few seconds two of his completed, smaller religious works in the Hermitage in a squeeze play.

Isaacson has a prosaic explanation for Leonardo’s (in)famous mirror writing, which is best read in its entirety. It demystifies this practice, and disqualifies Leonardo from the Rosicrucian Hall of Fame.

He was a contemporary of Niccolò Machiavelli, who signed for the city of Florence a contract commissioning Leo to paint a triumphal scene. Needless to say it was never completed. Isaacson supposes Machia and Leo were friends, but I rather doubt it. The evidence is circumstantial at best, and as personalities they had nothing in common. Geniuses do not always attract each other.

Still Isaacson’s book is extensively researched, measured in its inferences, and concentrates almost always on available evidence, which is almost always art, paintings, sketches, models, and drawings, much of it from the notebooks Leo always carried. He succeeds in bringing alive this man who could spend hours examining the condensation on a glass of cold water, drawing the shapes as they came and went, or simply staring intently at the glass as if it alone existed in the world.

The notebooks were numerous and many have been lost. Some were sold off to admirers on his death, and so valuable was anything of his that some notebooks were ripped up and the pages sold separately. In this practice was room for forgeries. Yet much of them remains and they are the only autobiographical source for this remarkable man. On the pages are his many interests, and lists of things he wanted to do, find, understand, know, and test. By the way, though he was pragmatic enough to keep it to himself one entry in the notebooks says that ‘the sun does not move.’

He was so remarkable that even in his lifetime apocryphal stories of his powers were circulated and these multiplied after his death. The journalist of the time, as now, were completely unscrupulous in the exaggerations heaped upon his name to peddle their wares. Thus he became encrusted with myth and legend. Part of Isaacson’s achievement has been to strip away those layers that readers may see the man within.

Skip to content