GoodReads meta-data is 384 pages, rated 3.91 by 5604 baseball fans.

Genre: Baseball.

Verdict: Sobering, entertaining, insightful.

Will sets out to demystify major league baseball by revealing its inner WORKings. Mission accomplished.

Where the uninitiated sees luck, talent, and inspiration, Will finds calculation, attitude, and preparation. Some of the latter is physical, to be sure, but much of it is mental. It is all W O R K.

Will selected four individuals as case studies, a manager, a pitcher, a batter, and an infielder. Along the way he salts the mine with anecdotes from other times, places, and players, making a rich dish.

Manager Tony La Russa’s abiding aim in the 1980s to advance the runner seems curiously old fashioned read in 2021 when that simple ambition seems from a lost world. Drag bunts, fielder’s choice grounders behind the runner, run and hit, switch hitting, delayed double steals, disguised cut-off throws, using the infield fly rule, all these now belong in a museum as millionaire hitters below the Mendoza Line swing from the heels as if an opposite field single is beneath the dignity of their signing bonus. There speaks the curmudgeon who will be heard from again below.

At times it seemed to this reader that there is a paralysing overkill in the analysis of the work; examine in minute detail any instance and it becomes unique. Whose on first? Free will or determinism?

Listen to the advice of that general manager, Francesco Giucciardini (1483-1540), who wrote that ‘it is fallacious to judge by example, because unless these be in all respects parallel they are of no use, the least divergence in the circumstances giving rise to the widest divergence in the angle of conclusion,’ History of Italy, p. 110. Just before dismissing Frank Gee as a pen pusher remember he commanded combat armies in the field long before the Dead Ball Era.

Spurious correlations abound: ceteris paribus, this batter swings at a slider outside on Tuesdays, but not Thursdays. Well that is what the data shows. Today is Tuesday, here comes a slider. Like life, baseball comes from a partly written script. There is determinism entwined with free will as vine to fence. That fact seems obvious to everyone but a sociology PhD.

I half expected it to be in the stars, though astrology has not yet been tapped by the baseballmetricians (aka sabermetricians). It will be one day.

The endless war of batters against pitchers is the heart of the book. Each tries to unsettle the other, using a very great deal of intelligence coupled with honed abilities. Who will blink first? To a batter the opposing pitching staff is a creature with ten arms coming him. The more so in the age of pitcher surfing when they come and go five, six, seven times in a game, if not an inning.

Who knew? John Sain (of Spahn and rain fame) bridged history, throwing the last major league pitch to George ‘Babe’ Ruth and the first to Jack Robinson, two of the immortals.

By the way, the eternal pitchers’ manual is the Book of Job: man is born to troubles. Nowhere is that more true than 60 feet and 6 inches from the plate on a ten-inch high mound. Lamentations for the passing of the fifteen-inch mound in the annus horribilis of 1969.

Speaking of wars of words, I enjoyed being reminded of Steve Carlton’s silent trances before going to the mound to show the world how to throw a slider, and his continued silence afterward. In a twenty plus year career he spoke exactly once at a post game press conference. As a result he became a favourite whipping boy of the ladies and gentlemen of the media for failing to give them copy. (Yes, I know SC went off the deep end.)

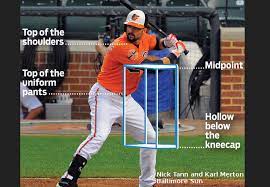

To the pitcher the batters are many and varied, and just keep coming, left and right-handed, short and tall, inside hitters and reachers in their infinite variety. Not even the strike zone is a constant (though I relish the always-on-top image of the strike zone now part of television broadcasts which may have brought some visibility and stability to this illusive Bermuda rectangle).

Here is a complaint. Buckle up! The chapters on hitting and pitching are very repetitive, right down to the anecdotes. I started to wonder if it had been proof read or if I was dreaming. Neither is a good sign.

Will comprehensively debunks the natural athlete assertion for the disguised racism it is. To take one example, Willie Mays was a close observer of pitchers who never forgot a move, and with experience got so he could anticipate moves both at bat and on base. As a fielder he was likewise a Cartesian who broke down the outfield into its smallest parts and mastered each of them by turns. He made it all look easy because he worked so hard at it. In the same way it was always said that magician with the bat Tony Gwynn was a natural. Really? Then why did he take five-hours of batting practice on playing days? Ten hours on off-days. By these unnatural practices he became a natural.

Here is a test for the baseball fan that will be inscrutable to the benighted. What these numbers represent? (Note the publication date of the book.)

511

.406

56

60

61

1.12

1,406

(I knew them all but the last, sorry Ricky.) No spoiler, figure them out or go home.

In baseball as in life numerical reduction has grown stronger. Like economic rationalism, McKinsey management, and Pokemon, reduction is a fad and will fade after doing a lot of damage in the hands of those who do not understand it, but cargo-cult it. Originally these were good ideas, but they have been destroyed by acolytes who did not know when to quit. Think of customer feedback. Good idea. Current practice has the effect of destroying it. NO! I do not want to give feedback on the experience of purchasing a bag of kitty litter! Communicating with customers is a good idea, but a dozen emails and text messages from Australia Post about a routine delivery is overkill!

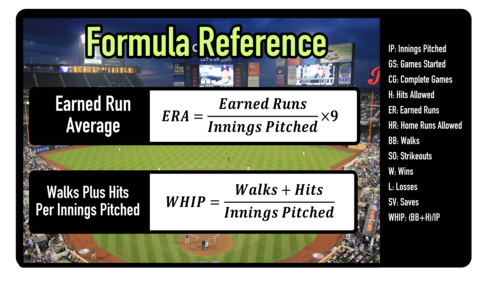

Statistics start as tools and soon become masters. Although the pedant must say that baseball has many numbers and few statistics, but most people, including Friend George, call numbers statistics just to confuse the children. A number is, well, just a number, say 6. A statistic is number subjected to some arithmetic manipulation, divided, multiplied, kissed on both cheeks, or something, like the ERA. That is the Earned Run Average, not the Equal Rights Amendment, Mortimer. (Yes, he’s back.) In the list above there were two statistics while the rest were numbers. I could go on about this but won’t in the interest of world peace.

Yet there still remains the fundamental prejudice for the long ball over winning games. The case in point that Will selects is Nebraska’s own Richie Ashburn whose achievements by any metric were remarkable without hitting home runs. In one of his best seasons he hit but one while dominating most games in which he played with fielding, throwing, running, and batting singles. And yet he is unheard of apart from diehard fans like moi. Then there is Bill Mazeroski who played second like no one before or since (even leaving aside 13 October 1960, a fine birthday-eve present for me). ‘Bill who?’ pretty well sums it up. These two were the perfect Tony La Russa players who played for the team and disappeared from memory down the dugout tunnel.

Loved that old chestnut, how do you pitch to a Henry Aaron? Set up your best pitch, throw it, and then run to back-up third. Found touching the encomium to ABG (if you don’t know who ABG was, hang up your spikes).

I return to my curmudgeon complaint above to note that Will agrees that basic baseball skills are sadly lacking in MLB and offers an explanation. Each year’s new crop of players mostly come from college programs. To get a return on the money paid to these recruits the drafting teams force-feed them into the Big Show. No matter how good the college coaching has been over four years with maybe 150 total games, it is paltry in comparison to four years in the minor leagues playing up to 150 games each year, thus 600 in all. Moreover, the college players are only part-time athletes for those years and full-time students (well, that is the legal fiction), whereas the minor leaguers are full-time athletes and so work at baseball three or four times more each week than a college player. Added to that, a multi-millionaire MLB newcomer is reluctant to practice Little League fundamentals, like bunting, throwing to a cut-off, the first base stretch, choking up on the bat, moving on the rubber, and so on. Likewise the management that gave these newcomers millions is reluctant to display their elementary deficiencies in training before the vultures of the media.

One of Will’s cherished pet peeves is the fashions in baseball stadiums, which even the 1980s were becoming entertainment centres and not cathedrals of the 108-stitch orb. That trend, and many others he reviles, has multiplied since the publication of the book. In these stadia the game on the field is one of many distractions competing for the patrons’ attention with restaurants, bars, music, museums, fish tanks, mascots (shudder!), clowns, more music, stand-up comedians in lounges, giant TV screens showing other games or even – gasp! – other sports and so and on. There are even padded chairs enclosed by glass! (Good grief!) Baseball is best appreciated on a hard seat exposed to the elements is the gospel according to Will. The dual use stadia of the 1980s he cannot abide, suited for neither baseball nor football, and used for both, and rock concerts!

Concern with public health and sanitation means I can no longer watch MLB games with their exquisite camera work of players spitting. While Will notes in one clanger of a scene this disgusting habit he does not make a sufficiently BIG DEAL of it, so I will. Yes, the constant spitting is tiresome, unnecessary, and, well, talk about cargo-culting. Is there data to show that spitting improves performance, George?

While less repulsive, but equally idiotic, is the war paint players apply to their faces. It is a fetish with no basis in fact but there are those stick-on dark lines under the eyes. Really, how stupid can you be. ‘I lost the ball in the glare from the lights on the dark skin off my high cheekbones, Coach, honest! This in a night game.’

I had hoped that Will might explain why we insist on calling these men at work boyish names, Johnny, Ricky, and so on. What’s wrong with calling a John a John? And by the way, George why is that Babe Didrikson was the last woman to hit a major league fastball?

Until 2016 George Will patiently explained the merits of the Republican Party to the uninitiated, but he gave up that Sisyphean task as impossible by that year, and said so in a loud voice.

P.S. Inspired by this reading I watched a few game highlights on You Tube. Superb camera work to be sure, and some snappy curveballs and some very nice plays, until …with his team behind by one run late in the game, a .215 hitter swung and missed at a third strike as the catcher dropped the ball. The batter turned slowly to the dugout walked away as the catcher retrieved the ball and lunged to tag him, and in so doing dropped it again. No matter the batter kept walking and the umpire then called him out as off the base path, I suppose. From the other world, I can hear Coach Kramer screaming his lungs out! Run!

P.P. S. That led me to the blooper videos where there are rich pickings from this young season alone, including outfielders who do not know how many outs there are, pitchers who do not cover home after a wild pitch (as two runs score), a third baseman with no idea where third base is, cut-off men who do not go out for the throw, but stand their ground waiting for it to come to them, a relief pitcher who threw a wild pitch on an intentional walk. I have to lie down just thinking about those.