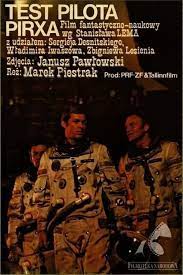

Pilot Pirx’s Inquest (Test pilota Pirxa) (1979)

IMDb meta-data is a runtime of 1 hour and 35 minutes, rated 6.4 by 916 cinematizins.

Genre: Sci Fi; Species: Red.

Verdict: Mixed

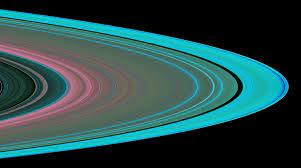

Space flight is routine, but Pirx is offered an unusual assignment by the United Nations. He is to captain a crew on a tricky mission to do some stunt flying through the Cassini rings of Saturn for some reason or other. That is the mission, but the purpose is to test the crew of five, one of whom is…Leon Trotsky! No, just kidding to see if readers are awake. But one of the crew is…a woman! Aha, got you there. No, nothing that radical. But one of the crew is inhuman! Yes, it is a Republican Senator.

Still with me?

One of the crew is an android that is so human-like that it cannot be detected by any means short of dissection. The mission is a test of this android to see how well it works with the other members of the crew and performs its role. It will pass itself off as human by acting stupid! None of the others will know there is a tin man among them. Ha! except They all know from the get-go. So much for Top Secret.

Pyrex – it was inevitable that either I or the autocorrect would fix his name – is reluctant to undertake this test but is persuaded by some reverse psychology when a commercial interest try to scare him off. We never see these villains again after act one. Why is he reluctant? No idea. There is some background noise about bots taking human jobs. Bad scab bots!

He should have listened to himself because instead of preparing the mission for the trick flying he spends all his time trying to figure out which one is Mr Data, the tin man. He is totally preoccupied with this identification. While he pins up a woman’s picture on his bunk we have no idea who she is. Evidently, neither did he.

The crew members know one of them is tin, and several assure the captain that it is not them, while another says he is it. It descends into a soapy space opera with all this confessing.

It seems to be three movies edited into one. First, we have the UN project and commercial interest who recruit Pyrex. Then we have the mission. Finally, we have a court of inquiry at the end that tells some of the mission story in retrospect. The continuity is, well, discontinuous.

With these chopping and changing, no character develops, motivations remain unknown, why does the tin man go bonkers? Maybe he read the script. Oops spoiler, rewind and delete. What is the inquiry about?

The production values at the outset and on the mission are good, but by the time we get to the court of inquiry we have a vast empty room because all the furniture must have been sold. The incidental signage is in English on exits, fire doors, stop signs, and the like. One scene was shot on location at Aéroport Charles de Gaulle, and another in a French chateau. That is expensive location shooting. The portrayal of the commercial interest is crude, but seems to offer some social criticism of the capitalist west, as does a scene in a topless bar that is there only to be there, though it did briefly arouse the fraternity brothers. It is supposed to be a din of capitalist sin crowded with folk, jiving to decadent music in a vast room. But there cannot be more than a dozen revellers going through the motions with mechanical precision at one end of an otherwise empty room.

By the way, most of the crew have anglo names: Harry Brown, John Calder, John Otis, and the other one.

The biggest problem is why Pyrex is so focussed on the identity of the tin man and not on doing the job. By the way, women figure in the story as receptionists and dancers in the bar scene. That’s it. As above, we do not even get the ritualistic love interest for Pyrex.

To some extent Soviet science fiction differs from that the United States. Whereas in US science fiction space is full of threats, invaders, monsters, asteroids to destroy earth, ghosts, or black-widow vixens, wizards, man-eating flora, and so on. It is up to one or two intrepid Americans to fend off these menaces. When the unstoppable Roger Corman bought Soviet science fiction films and recut them with new dubbed sound tracks for the D (as in drive-in) market, he inevitably cast them as Americans battling a hostile universe, like something straight out of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan. No doubt he did so on the assumption that was what the audience wanted.

Soviet science fiction is more likely to emphasise international cooperation, and when aliens are encountered it is because they need help which the Soviets offer. (Maybe Ukrainians should try to pass themselves off as aliens.) Tensions arise from conflicts among the crew or psychosis, and less often from external threats, apart from the difficulty of space flight itself and evil Westerners. The Soviet films are often much more realistic about space flight. They seldom feature banana chairs on the flight deck, walks on Mars with scarves for face masks, or navigation with a 12-inch school ruler – all of which I have seen in Yankee SF. These red films seem dedicated to showing what the audience should know, not what it wanted to see. These generalisations rest on the maybe half-a-dozen USSR films I have seen and of course there are plenty of exceptions.