Expedition to Disaster (2013) by Philip Matyszak

Good Reads meta-data is 192 pages, rated 4.25 by 36 litizens

DNA: Academic.

Genre: History.

Tagline: They make the same mistakes every time.

Verdict: Chapeaux!

With the verve, energy, exuberance, and creativity characteristic of Athens its response to a stinging defeat by Sparta was to go on the offensive in 415 BC to far Sicily, there to subjugate its fellow democracy at Syracuse.

The primary source for these events comes from an involuntarily retired general, Thucydides, in his History of the Peloponnesian War. As with Machiavelli, Thucydides’ own meaning has largely been lost by contemporary writers seeking a classical authority for their own opinions who view it in a hall of distorting mirrors and see what they want to see in the text. A recent example is Graham Allison, Destined for War (2017). For an antidote try my essay of archeology in the Antioch Review (65 [2007]1: 173-185). Get clicking.

There are other sources, mostly fragmentary, and the ever increasing excavated evidence as more ground is dug up to build apartments around the Mediterranean Sea and relics are discovered, enriching the museum collections but putting the real estate developer out of business.

Matyszak mines these resources but in the main the book is a gloss on and homage to Thucydides. And that is good enough reason to read it.

Thucydides shows how men have acted under pressure and that predicts how we will act under a like pressure today or tomorrow. To predict the future learn the past. That’s why we read him – yesterday, today, and tomorrow is between the covers of a book.

Whereas Herodotus recorded any story he heard about dragons, sea monsters, three-legged men, talking dolphins, magic rings, flying trees.… Not so Thucydides who asserted nothing he could not confirm by evidence, reason, or both. He had a network of contacts in military and commercial life in Athens and its allies that extended to Sparta itself. These he used to research his book.

What is more remarkable to contemporary sensibility is that Thucydides kept his opinions to himself. He passes only one personal comment in his 500 plus pages when he wrote that Nicias, he least of all men, deserved the terrible fate that he suffered.

Thucydides quotes about 140 speeches; he himself heard some of them, and interviewed auditors who heard the others. But he also wrote what, after his research, he thought would have been said in many instances. Then there is that outlier, the dialogue on Melos. My take on that is in article cited above.

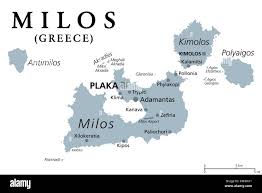

By the way we spent a few days on Melos once. I climbed to the top of the tallest point to look for the Athenian fleet, and later brought home a pebble from the beach where they could have landed.

After battles he visited several of the sites to see the terrain, sift through the remnants, and talk to local residents, if there were any. He acquired specimens of the weapons the soldiers of different cities used to assess their value. Thucydides tried living on the rations that besieged garrisons had to endure. He walked the ground armies travelled to test the conditions. Moreover, he visited Sparta to hear that side of the story. Some speculate that he also sailed to Sicily during this campaign to see for himself the city of Syracuse which is certainly described in a great detail in his text. More than once he does, indeed, sound like an eye witness. Several historians have inferred that he interviewed some of the opposing generals.

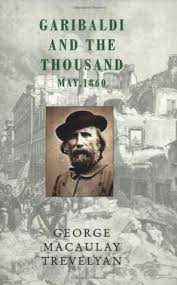

George Trevelyan made a similar hike to re-enact Garibaldi’s descent on Rome, see his Garibaldi and the Thousand (1909). He carried a pack and lived off the land as he went much the Red Shirts did.

The debacle at Syracuse is painful to read about because the drama always comes to the same climax. Leaving aside the complexities it is this: to conquer Syracuse Athens sent a force of 40,000 experienced veterans of citizen hoplites, mercenaries, and allies. To defend Syracuse Sparta sent one man. The Athenians lost as comprehensively as the Germans lost at Stalingrad. Some military advisor that one man! Read Thucydides for details.

When I read of the Sicilian expedition, I am remind of this passage about Gettysburg:

“It’s all now you see. Yesterday won’t be over until tomorrow and tomorrow began ten thousand years ago…. There is the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863…it hasn’t happened yet, it hasn’t even begun yet, it not only hasn’t begun yet but there is still time for it not to begin.’ William Faulkner, Intruder in the Dust (1948).

“The War that Never Ends” (1991) is a documentary film portrayal of the whole war. It is low key and spare with recitations of key passages, including Melos, and the debacle at Syracuse where Athenian democracy crashed with imperial and tyrannical overreach. See it on You Tube.

While I am assigning homework, see also Donald Kagan, The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition (1991). It is accompanied by three volumes that chart the rise, maturity, and corruption of that empire. (There is a one-volume summary for the faint of heart.)

A theme in International Relations research which has influenced recent U.S. foreign policy has been that democracies do not go to war with each other. It follows in the seminar room that promoting democracy promotes peace. In this case both Athens and Syracuse were democracies and Athens went to war at the enthusiastic behest of its democratic majority, giving the lie to that generalisation. (It might be worth noting that Hitler rose to office in elections, whereas Churchill did not.)

The author has some very nice turns of phrase and offers a spritely prose that engages even a jaded reader like me. My efforts to put his name below the picture failed.