Convenience Store Woman (2018) by Sayaka Murata

Good Reads meta-data is 163 pages, rated 3.69 by 280,087 litizens.

Genre: Fiction; Sub-species: chick-lit.

DNA: Japanese.

Tagline: Irasshaimasé!

Verdict: Meursault with a purpose.

Keiko didn’t fit in. This fact she had learned in primary school when, during a recess, two boys were fighting and everyone shouted for them to stop. She stopped them. A gardener’s spade came to hand and she whacked one of the combatants with it. End of fight. She had done what everyone wanted, and now she was the one in trouble. Go figure!

There were many other ways in which she was an odd duck. She showed no interest in the girlish concerns of clothing, cosmetics, boys, family, and so on. She just drifted along on the ebb and flow of those around her, having learned to conceal her indifference to these matters and much else, well nearly everything else. For camouflage she copied the dress, mannerisms, and speech of those around her, but none of it had any inner resonance. She is an A.I. robot in these ways, programmed from the outside in by the environment.

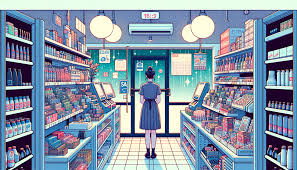

When she graduated from high school she got a part-time job at Hiiromachi branch of “Smile Mart,” a convenience store, and found her niche. Here she comes to life with energy, initiative, commitment, interest, and more. The growth and expression of her symbiotic relationship with the convenience store is the core of the novel, and it is charming, if a little unnerving. (Footnote: See Michel Foucault on life in the social machine.) The store gave her purpose and structure and she dedicated herself to it in return. She became obsessed with personal hygiene because the store required it. She ate a proper diet and slept the requisite hours so that her strength was equal to being on her feet during eight hour shifts. She no longer had to decide what wear but happily donned the prescribed uniform. She learned to use morning weather forecasts to stock the shelves, to know when regulars would arrive, how to scan items and make change instantly.

But most of all she had learned to read the store, to know by the sounds, smells, drafts when something had to be done. The crinkle of cellophane wrappers might imply a need to restock shelves. A draft of cool air, a refrigerator door was ajar. A certain click might mean a rack is empty. The store was mother and child to her and she cared for it in all ways.

She always volunteered for more work, not because she wanted or needed the overtime pay (since she had nothing to spend it on) but because it kept her focussed on what the store needed. The store shielded her from the pressure to conform to the expectations of her parents, her peers, the society,…and life beyond the store and in return she cared for its needs.

It may sound dopey but it is done so well that is only a belated second thought. Meursault of Camus’s L’Étranger would get it.