Roland Allen, The Notebook: A History of Thinking on Paper (2023).

Good Reads meta-data is 416 pages, rated 4.50 by 92 litizens.

Genre: Non-Fiction; Species: Social History.

Verdict: One for trivial pursuits.

Tagline: Get it down on paper!

It was a double whammy. First paper and then the convenience of the notebook to carry it around.

The paperful office was the technological marvel of the age. Papyrus, clay, and parchment were the media before paper. Papyrus won’t grow anywhere else but the shores of the Nile River, and it does not travel well. Clay, well impermanent and easily changed. Parchment, expensive and also easy to alter. Hence palimpsest. None of these media facilitated commercial activity beyond goodwill and memory. Altering something on clay or parchment was child’s play. That way lies fraud. Keeping either quick notes or detailed records on them was not feasible.

Then a binder of books of parchment, began to experiment with flax and hemp, and discovered he could make paper. Soon an experienced worker could make 4,000 sheets (slightly larger than A4) a day. The binder used this paper to record the accounts of his business, and was able to do so in a detail that exceeded everyone else. Soon others wanted to do the same and he began selling them paper.

All this occurred about 200 kilometres from Florence, and businessmen there heard of and tried this new development. Paper gave them a competitive advantage in the detailed records they could keep. In time, letters of credit replaced the risky and difficult task of moving gold and silver coins. These letters made the Florin of Florence the stable currency of choice around the Mediterranean and as far north as the Netherlands. In the long fallout the Dutch currency was called a florin well into the Twentieth Century.

Then the second innovation occurred: Double-entry bookkeeping. (See Jane Gleeson-White, Double Entry reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Click away.) This method of matching assets and liabilities adding up to zero was a revolution comparable to Copernicus’s conceptual breakthroughs at Padua. Florentine business flourished with these new found intellectual technologies.

Ledgers, day books, receivables, inventories, catalogues, expense sheets, contracts, and more were quickly and easily recorded and were relatively fraud proof.

Popes made use of these technologies to distribute and receive funds from the Catholic Empire. The Medici became the preferred agent for a number of Popes, and profited greatly from it.

From the Thirteenth to the early Sixteenth Century Florence bustled, and one of the ways the rich indulged themselves was through art works. To save their souls they commissioned religious art, and for their own diversion private art in oil, canvas, marble, granite, and more.

All of this artistic explosion was worked out in notebooks, which became essential to artists, who could now do drafts, studies, cartoons, and the like, as Giotto may have done to create the lifelike figures he did.

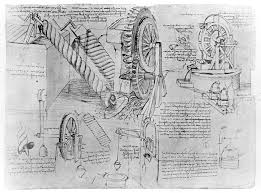

The most famous notebook user among artists, was of course Leonardo da Vinci who recommended the constant use of notebooks. He carried one affixed to his belt. Mostly he used them for sketches of the constant motion of nature, but he also recorded plans in them by mirror writing and in a code. He filled thousands of pages only a fraction of which remain.

Likewise, later the irascible Isaac Newton made extensive, life-long use of notebooks to work out his mathematical ideas. Historians of science have used them to map the evolution of his concepts.

Paper also fuelled European exploration when Portuguese navigators started to keep logs, draw charts, or map islands with fresh water. These innovations were soon taken up by Portugal’s ally, England and these technologies made the world more familiar and smaller.

The Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus started with notebooks but switched to cards in developing his system of nature.

When the hospital practice of intensive care began in a Danish hospital during a polio epidemic, the notebook, monitoring patients, was almost as important as the tracheostomy tube.

Agatha Christie always had a notebook at hand and filled hundreds of them with ideas, snatches of dialogue, room maps, plot ideas. Since she worked on several novels at once, alien that she was, and she did not date the notebooks, researchers make careers out of relating the finished book to notes scattered through dozens of notebooks over years. It seems she read back over the notebooks periodically and extracted material from them years later.

The police ‘inspector’ was so named because when shifts changed his job was to inspect the notebooks the Bobbies carried wherein they recorded their rounds which were countersigned by worthies along the way to prove the officer did indeed do the assigned round. The worthies might be Anglican vicars, school teachers, shop keepers, or publicans. The police notebook was thus in the first instance for management control. But officers soon began using them to record observations and events on their patch as further proof of their diligence. The police notebook as we knew today on cop shows came, like most innovations, from the bottom up.

I found the opening product placement add for Moleskine put me off but I kept at it. For years I carried a notebook in a back pocket and there are shoeboxes of them in the office closet. I still use them to keep track of my gym activities. But these days to make notes I use Siri.