The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (1996) by Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers, III.

Good Reads meta-data is 390 pages, rated 4.27 by 33 litizens.

Genre: Non-fiction.

DNA: baseball.

Verdict: Mr Rogers and Mr Roberts tell all.

Tagline: You can take the boy out of the ball game, but you can’t take the ball game out of the boy.

Forward by novelist James Michener published by Temple University Press perhaps in recognition of the social impact of sports, which seems more enduring than institutionalised religion these days. Hope, salvation, compensation, distraction from woes, identification with something larger and meaningful, sports gives these to a lot of people.

First half of the book is a history of the Philadelphia National League Franchise from 1915 when it went to the World Series to 1949 when, after long years in the wilderness, it made into the first division with a winning record. Robin Roberts (1926-2010) was one of the Clydesdales who pulled that wagon into the Winner’s Circle.

Based on extensive interviews with surviving members of the 1950 team and written largely from Roberts’s point of view, a modest and unassuming one. It recounts many games and the stresses and strains both on and off the field with a candor made possible only by Jim Bouton’s barrier breaker Ball Four of 1970, which might have been the first book about baseball to acknowledge that players were fallible and friable human beings. The Society for American Baseball Research has opined that Bouton’s is the most influential book ever written about baseball for that reason. Amen to that!

In these pages Roberts and Rogers give credit where it is due to the players who made the 1950 Philadelphia Phillies champions. A few tidbits follow in no particular order.

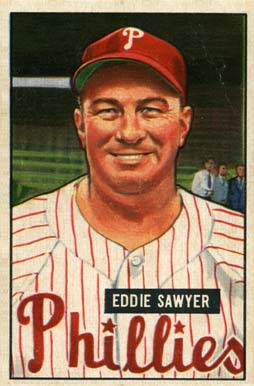

There was a new manager in 1949, replacing an aggressive and assertive fellow who did a lot of yelling while the losses mounted. In came Ed Sawyer, called the Professor by his players because he had an advanced degree in biology, a subject he had taught at Cornell where he coached the baseball team. Sawyer was, to say the least, mild-mannered. He seldom convened team meetings, never tried to motivate players by yelling at them, conceded the importance of family lives (births of children, illness of spouses, deaths of parents), did not tell pitchers what to do, and never, and this is much stressed in the book, second guessed after the fact what anyone did. So different from so many ex post facto coaches and so-called colour commentators who always know what should have been done.

Aside from creating an atmosphere of calm confidence, Sawyer also convinced the ownership to invest in new uniforms with a red pinstripe, perhaps to capture some of the reflected glory of the New York Yankees blue pin stripes.

Sawyer was the antithesis of the most well known and still remembered manager of that era, Leo Durocher, who always made himself the centre of attention, and over-managed enough to earn a McKinsey degree. He would certainly fit in the way the game is played these days: over-managed.

Sawyer believed in putting the players on the field and letting them do what they did best.

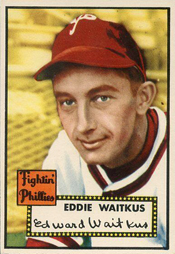

That was not always possible. To wit, All-Star first baseman Ed Waitkus missed most of the 1949 season and seemed unlikely for the 1950 season when a stan shot him. It’s a long story and none of it is good. A woman became obsessed with him, her apartment was plastered with all manner of his pictures and newspaper cuttings from the sports pages that mentioned his name. Then one day, perhaps, realising she would never possess him, she exercised her constitutional right to bear arms and in a hotel hallway shot him with a rifle. He did recover from the lung injury but was never quite the same again. This incident, by the way, is the seed of Bernard Malamud’s love letter to baseball, The Natural (1952). Justice being what it is, she was never tried but confined for psychological assessment and then released in 1952. Waitkus did not press charges but the team hired a body guard for him when she was released. Details can be found in John Theodore’s Baseball Natural: The Story of Eddie Waitkus (2002).

Fielding the best players in 1950 meant putting Mike Goliat at second base. Previously, he had played first and third, but the team had established players at the corners, and someone had to play second. He volunteered to try, and stuck to it. He made an adequate fielder and a modest hitter, at least above the Mendoza Line. (The cognoscenti know what that means.) But he made two other contributions to the team. According to Roberts, Goliat was a cheerleader of sorts who always tried to get the others to focus on the positive, even in defeat. And also, hidden in the aggregate statistics of his batting, is the fact that he absolutely owned Don Newcombe of the arch rival Brooklyn Dodgers and most of their other pitchers. HIs batting average against the Dodgers was well over .350. Because these Dodgers were locked in a race with the Phillies their ace Newcombe invariably pitched against them and Goliat feasted, typically going 4 for 5 with a couple of extra base hits, and even one of his few home runs. When the Phillies beat Newcombe, and they did, it was because Goliat was scoring. Of course, Roberts is too modest to say it, but it was also because he was shutting out the Dodgers’ many big bats.

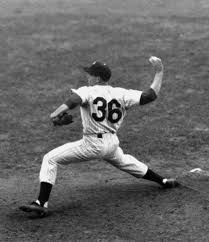

Roberts was not an overpowering fastball pitcher like Sandy Koufax nor did he have a table drop curve ball like Bob Gibson, but he did have preternatural control of all his pitches. This mastery was born of practice, but then everyone practices. But a hint at what set him apart is to be found in his comment that he seldom noticed the weather, the crowd, the catcalls, the cheers, the jeers, the wind, the noise or anything else. When he stood on the rubber atop the 15-inch mound there was just him and catcher’s glove. He sometimes had to be told the game was called off because of rain. He hadn’t noticed when pitching in it. More than once he asked his wife if there had been a big crowd at a game. He hadn’t noticed.

The Phillies beat the Dodgers for the National League Pennant in the last game on the last day of the season in the 11th inning at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn against that man Newcombe with Roberts holding the formidable Brooklyn bats to one run, and Mike Goliat getting four hits. Two days later they met the dynamic New York Yankees and were roundly trounced in four games, three by one run. Yes, the Yankees had a superb team and the Phillies were doomed before the umpire said the sacred words of ‘Play ball.’

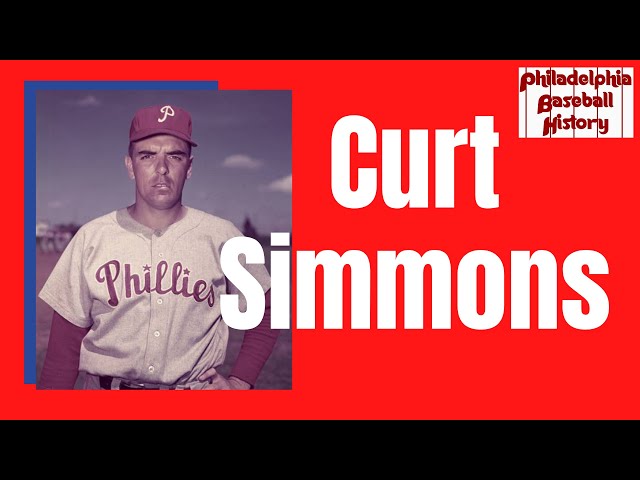

Ace left-handed pitcher Curt Simmons was called to active duty for the Korean War and left the team in September. The third starting pitcher Bubba Church was hit in the face by a line drive that same month and went on the injury list. Then the fourth man in the rotation was carrying a suitcase on a stairway in a train station when he fell and twisted his back in what became a lifelong disability. When the Series started the Phillies were very long shots with only one of their four starters available, that is, Roberts who had, two days before, pitched an eleven inning game, well over the magic pitch count of today.

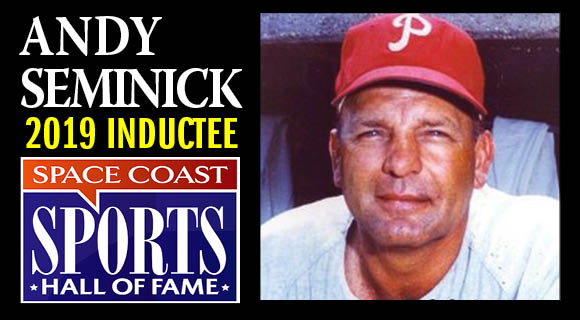

But wait there is more! The starting catcher, Andy Seminick, broke his ankle in that last game with the Dodgers. He played on, including the World Series, shot full of novocain and taped toe to knee. This, by the way, was not the last disaster for this team. When Simmons returned the following year, he tested his new electric law mower with his foot. Since it was silent, he could not tell if it was running so he struck his toe under it to see. He saw…a lot of blood and a career-ending injury. (Though in fact with a prothesis and agonising physiotherapy he did make a comeback.)

As quickly as they had arrived at the top they fell to the bottom of the heap for years to come.

The sobriquet ‘Whiz’ was created by the pressmen in spring training in 1950 (p215) to reflect on the fast finish the Phillies had made in 1949 and the very successful spring training they had. (Wherein Roberts struck out Ted Williams in an exhibition game with a slow curve. For the record, Williams had his revenge in the next at bat, hitting a home run off Roberts). The nickname might also have been inspired by the popular radio program of the day, ‘The Quiz Kids,’ who answered all manner of trivia questions. However, the Phillies’ roster was not appreciably younger or smarter (see the reference to a lawn mower above) than those of other teams. Subsequently, it had another application to refer to how fast the Phillies faded from NL pennant contention in the following years.

Partly thanks to the efforts of James Michener and others, Robin Roberts was inducted into baseball’s Vahalla at Cooperstown with a career record of W 286-L 245 with 305 complete games. At one point he pitched 28 straight complete games, five of them had extra innings. Because the Phillies barely averaged 2 runs a game in his tenure, Roberts, one member of the nerd kingdom estimates, lost more than 50 games by one run. In that World Series he pitched 11 earned runs scoreless innings in two games, and yet lost one because of an error. Like many others, he found it hard to quit and hung on MLB for 18 years.