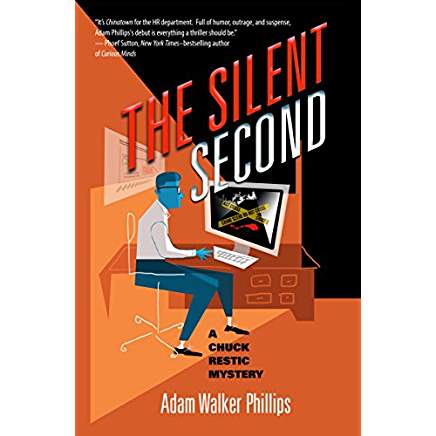

Chuck Restic is a human relations manager in a large firm in La La Land. HIs career peaked years ago and while his star descends that of his wife, a property lawyer, ascends and they part company without acrimony.

Now Chuck has time on his hands and the hum-dum of the office offers little distraction. In response to a complaint from a employee he talks to Ed about his cologne. Yes, about his cologne. An explanation is below. Chuck finds Ed a nice fellow.

A few weeks later quite by accident Chuck learns that Ed disappeared shortly after that interview. Time passes and Ed does not return. After four weeks AWOL the corporate policy is to clear Ed’s cubicle, box the contents, and mail it collect to the listed address. He is sent down the Corporate Memory Hole.

Chuck decides to pass some time by taking the box to the address by hand. In so doing he is gradually drawn into a real estate swindle in which Ed himself was somehow involved. But when Ed’s body is found, it gets worse.

There are some very tough guys around who fancy themselves to be the Armenian Mafia, Lincoln Heights Branch. They may be tough but the smart money is played by a zillionaire who is pulling all the strings.

Along the way, Chuck finds solace with a police officer who throws herself at him, a fact he accepts as his lot. Too bad he had not seen ‘Funeral in Berlin’ (1966) where Harry Palmer realises immediately that Eva Renzi is up to no good when she throws herself at him. Poor Chuck.

Chuck is bored at work and idle at home so he starts nosing around and gets in deeper and deeper. Then one of his buddies is murdered and the plot gets thicker quicker. While I remembered Harry Palmer’s self-deprecating cynicism and saw the punch coming, it is played out very well.

There are technical details about Lost Angeles real estate that provide much of the mystery, and while the Armenians are much in evidence, they know there are bigger fish in this sea. Chuck doesn’t and keeps stumbling around.

But after a thirty year career of insufferable Power Point presentations, unending off-site retreats, excruciating 360 degree reviews, maniacal KPIs, and nightmarish McKinsey-speak, being beaten up by Armenians comes as something of a relief to Chuck. Still all those years in HR gives him access to a lot of personal information about personnel past and present and even applicants that he puts to use. Futhermore, it has taught him how to read between the lines in files to find out more. He also has contacts among freelance journalists who in the past have dug out information for him; in short, there is a solid base for his investigations.

As to the cologne, this is the story. An employee lodged a formal complaint against Ed for wearing so much cologne that she became ill. Mind, Ed did not work near her cell, er cubicle, but only walked by it once or twice a day. Still she filed the paperwork, and once filed it fell to Chuck to deal with it. It all seemed so realistic.

The complaint was vexatious. The complainer had been with the firm less than two years, during which time seven formal complaints about comparable matters had been filed, while the complained did little productive work. But the complainer, once hired, was untouchable, being a forty plus, pregnant, black woman who ticked all the demographic boxes for a huge personal injury suit from giant uncaring oppressive corporation that had made mistaken of hiring her. She had to be placated at all costs. Ed, on the other hand, had been with the firm for more than a decade, was extremely productive, corporate loyal, but as a white, middle-aged man he would never win a lawsuit. Such is the corporate logic in these pages.

Adam Phillips

Adam Phillips

While the plot is straight out of Raymond Chandler with updates and located in the world of real estate, the corporate backdrop strikes a cord with this reader. The author produces an interesting variety of characters and gives each a distinctive voice. There is much travelogue of the Lost Angeles where people live and work well away from the Tinsel Town stereotypes. The corporate world and the real estate context are refreshing. This is the first of a series and I look forward to reading another.

Author: Michael W Jackson

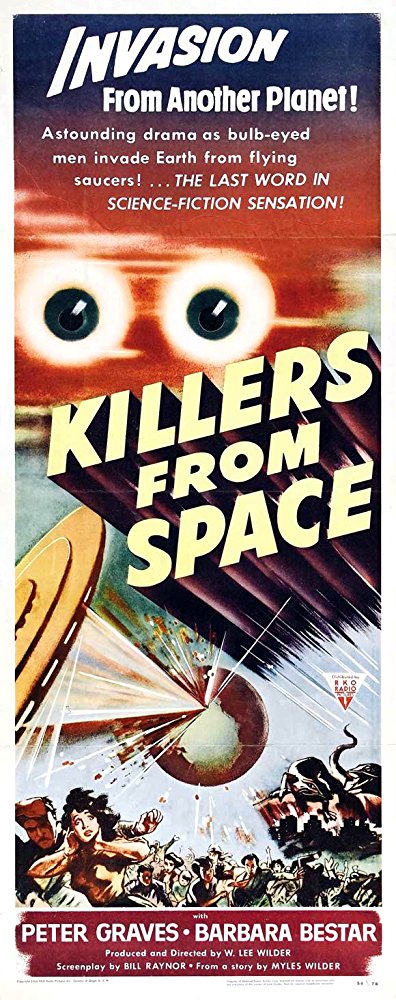

‘Killers from Space’ (1954)

Peter Graves made this for a Wilder in 1954, the year before he had made ‘Stalag 17′ for a Wilder. What a different a Wilder makes. More on this enigma at the end.

First the IMDb facts, it runs for 1 hour and 11 minutes of Dali time, and the 1566 ratings average to 3.1/10. That is right at the Mendoza line.

Grave Peter is abducted by aliens, a frequent occurrence for those from Minnesota, but instead of the anal probe that St Paul of ‘Paul’ (2011) made (in)famoius, they bring him back from the dead with a heart transplant. He never says ‘Thank you.’

A lobby poster straight out of Faux News

A lobby poster straight out of Faux News

What happened? Grave Peter is a nuclear scientist who knows as much as Kevin about nukes, and is participating in above ground nuclear testing in Nevada (which then as now is not much good for anything else). Since the tests are atomic bomb drops and the technicians, politicians, generals, grunts, journalists, and scientists stand around with sun glasses on to watch, there is also plenty of longer term killing right there. In addition, everyone smokes.

The plane Grave Peter is in mysteriously crashes and is incinerated. The assumption is that he was barbecued in the pile of ash. Grieving Wife sheds a tear. Wooden colonel stiffens his upper lip. The next test is scheduled. Must not hold up progress to Armageddon.

Then Grave Peter in a ragged jumpsuit walks home in a daze. Whacko! He survived! But how? He is stunned and remembers nothing. Not even the massive butchers’ scars on his chest. The fraternity brothers were sure they would remember something like that no matter how OBs they drank.

He is physically fit after a shower, shave, coffee, and a pipe (being a tweedy scientist he smokes a pipe so he can leave a trail of ash for the plot). Yet he remembers nothing. Mondayitis? While the examining doctor remarks on the scars, he does not investigate them in any way. Guess it was a short 15-minute consultation on the Medicare scale and there was no time for more.

The shadow of the Cold War falls with a thump. What if this Grave Peter is a substitute planted by you-know-whom. The real Grave Peter could not have survived the crash. Ergo this one is an imposter. What other explanation could there be, Erich? This possibility does not explain the scars but no one seems to care about that. He is sequestered in the base hospital under observation, i.e., hospital arrest to await the Good Doctor to come and fix him up. But he is compulsive about carrying on. This arouses more suspicions by the wooden FBI man on the scene.

With the touching faith in drugs of B-movies, they shoot up Grave Peter with a truth serum, and he tells all. This is one blabber mouth. It goes like this:

He awoke on an operating table just as a heart, he says his, but he would wouldn’t he, was stuck back in his chest by a mechanical arm attended by the losers of a Ping Pong match.

Grave Peter in post-op.

Grave Peter in post-op.

He raves about those eyes. ‘Those eyes!’ He does this a lot.

Then the drug wears off and he wakes up in the hospital to find the doctor, the colonel, the stooge, and the FBI staring at him liked he just confessed to liking the Osmond Family’s music! Disbelief isn’t the half of it.

Conclusion: He’s no commie plant; he’s crazy. They change the locks on the hospital door. Well, no they don’t. And he is now determined to clear his name alone! Not only is he not a commie, he is not crazy, though why else did he accept this part? Grieving Wife is nowhere to be found. Another abduction? We’ll never know.

He breaks into the top security military base, he breaks into the top security safe, where he leaves pipe tobacco ash (was this an unconscious plea to be stopped?) and steals the nuclear test data.

He drives into the night, since the budget did not run to lighting, and sticks the top secret results under a rock. Oops! This is the very rock the FBI man is standing on in Bronson Canyon. Of all the rotten luck! There is punch up and Grave Peter flees. For a tweedy scientist he can hit below the belt with the best of them.

While I was raiding the refrigerator, he got himself into the aliens’ den where the Bug Eye in Chief talks to him. ‘We speak all languages,’ replies bug-eye numero uno Grave Peter’s amazement that he speak English. Polyglot, uh, a sure sign of someone up to no good. BEiC then explains to him in detail the nefarious plot in the best Dr No fashion.

They have destroyed their own world thanks to the climate change deniers and now have to relo. Earth will do, but first they have to rid it of us humans. To do this, sparing Occam’s razor, they will use the radiation from nuclear tests to charge the batteries in the hot house where they are breeding giant spiders and ants (some of which escaped to ‘Them’ [1954] – much the better film) and once they have enough creatures for a feature, they will unleash them to devour humanity. Gulp! One suspects a sequel in the works.

Now the Earth will be overrun with big bugs, but not to worry, then the bug eyes will spray DefCon to kill the insects, whose rotting bodies will fertilise the soil. See, a grade A plan with KPIs galore. In this case of McKinsey speak KPI means Killing People Immediately. Grave Peter is impressed with the grantsmanship of the plan, but instead of throwing in with them as a nuclear expert and getting promoted to Honorary Bug Eye, he escapes.

No gratitude has he. While babbling Geordie-speak he rushes to the one power planet in the place and brandishing a pistol that came with the elbow patches on his tweed coat, he throws all the switches to Off, including the MASTER Switch. Darkness fell. Iron lungs stopped, ‘I Love Lucy’ went blank. Surgeons said ‘Oh Oh.’ Nine months later there were surprises. But the power is off only a ten seconds, so maybe not so much of the latter.

The wooden ones, the colonel, the FBI, the stooge, Grieving Wife are now looking for a net to throw over Grave Peter when KABOOM! That was the sound of the aliens’ den blowing up, just as Grave Peter predicated! The mere sound of the explosion clears everything up and he is welcomed back on the road to Armageddon.

The end.

Seen today there is a message about destroying one’s own world by electing idiots, and another about the dangers of radiation. But neither of these was intended at the time. Just plot devices though a few films like ‘Rocketship X- M’ (1950), reviewed elsewhere on the blog, do have an ever so carefully put case about the dangerous of nuclear radiation. Enough to get the screen writer a mug shot it was. But that was exceptional. In 1954 any doubts about the safety of nuclear energy and weapons were Commie tweets.

The only thing a sensible viewer remembers from this celluloid is the bug-eyed aliens. There are conflicting stories about this effect was achieved. The budget did not run to having anything made by a optician. They look like Ping Pong balls and that is the usual explanation, cut in half, with a black dot painted on them in which is a pin hole so the actors with them glued to his eye sockets does not stumble over a paycheque.

Though there is another story according to which Wilder himself came up this idea. He opened the refrigerator at home to get a beer and noticed the white egg rack built into the refrigerator door. Hmmm.

He yanked the rack out, cut the egg cup receptacles off, and ‘Voilà!’ alien bug eyes without the expense of Ping Pong balls. Because this is a difference without any significance, it heats up cyber space as adherents to the Ping Pong ball explanation dispute with Egg Rack believers. The tweets fly. Good thing they don’t have nukes.

Ping Pong balls or egg cups? You must decide.

Ping Pong balls or egg cups? You must decide.

Peter Graves went on and on. His last credit was in 2010, the year of his death. This man seldom said no. Witness ‘Airplane!’ (1980). In the latter part of his career he often played, parodied, himself, grave, stalwart, gravelly voiced, and wooden. In 1954 he was impossibly handsome and trying very hard. But maybe he should have said no now and then.

Lee Wilder produced and directed ‘Killers from Space; hot on the heels of the ‘Snow Creature’ (1954). Since a Lee Wilder movie took no more than a week to film, he could turn them out when there was coin. Coin? The story goes that Lee left his native Austria and migrated to New York City where he became a very successful hat maker. Whether for men or women is a question only further research could answer. His younger brother Billy was cinema-struck as a boy and had gone to Berlin to learn the business.

Reading the blood signs on the street in Berlin, Billy wanted to go the Amerika, and brother Lee paid his way. Billy said thank you and took train to Lost Angeles where talking movies were the go, and he saw his future in that. Off he went, and the string of commercial and artistic successes is now legend. He made one of his masterpieces, ‘Sunset Boulevard’ in 1950. By then he was so well established he could defy Tinsel Town conventions, command extraordinary budgets, attract great stars out of retirement, make a star out of an also ran..…

Lee Wilder

Lee Wilder

Is this a case of inverted sibling rivalry? Older brother Lee then sold his New York City business and moved to Lost Angeles and set himself up as an independent film producer with his son Myles, who did not have to be paid, as the screen writer.

My five minutes of web research indicates that there was no rupture between the brothers, but though they both made films and lived in Lost Angeles they never met there and when they bumped into one another, they exchanged nods, not words, and went on.

‘Snow Creature’ (1954)

IMDb 3.1/10 from 711 votes at 1 hour and 9 minutes of Dali time.

This title is often found on those list of films that are so bad that they are fun to watch. Just about everything is wrong. Error spotting keeps the viewers interest. Nothing else does.

An American scientific team scales the Himalayas to find rare botanical specimens. This team has only two members, the botanist and a newspaper reporter to publicise the investigation for the ‘Daily Plant.’ To ascend the mountains they hire locals to schlepp the gear, including a radio (so they can follow the World Series?). They encounter the abominable snow man! Yeti they do! They subdue him and ship him back to Lost Angeles where half the film is set in the dark. He escapes and wreaks so little havoc few in LA would notice. The forces of order are mobilised and slay the beast. End of story.

At least half the footage is stock film of airplanes landing and taking off. Nearly all the shots of the actors are in the middle distance. No close ups. A sure sign of a tip-jar budget. Shots of the trekkers are repeated again and again. The one close up of Abominable is repeated three times. The first time it was effective when he stepped back into the darkness. Less so on each repeat. When he is photographed on a slope in the distance, he looks so awkward and fragile that a gust of wind would level him. Some threat.

Another sign of a micro budget is that much of the story is told through voiceovers and not dialogue. That indicates no sound man on the payroll. Nor is anyone credited with make-up in the credits, so Abominable had to do his own. He is clearly wearing a two-piece fur suit. He is seen only once in a close up, and he looks wrapped up like the invisible man.

The fraternity brothers liked the footage of aircraft. In the first, the voiceover ponderously says they are flying into Bombay. Time to change airlines, folks! On the ground beneath the aircraft clearly visible are the pyramids of Giza. That pilot missed India! Cairo, Bombay, what’s the difference?

But wait, there is more. Later after boxing up Abominable (on that more in a moment) the voiceover has them landing in Lost Angeles. Hmm, yet beneath the aircraft we see the Statue of Liberty from New York City Harbor. No continuity editor is in the credits either, though this blunder is beyond the pay grade of a continuity editor.

Those instances indicate the quality of this celluloid from the Dream Factory.

The natives who figure in the first half as bearers are Sherpas, only one of whom is endowed with a name. The others go by ‘Hey you!’

But wait, there is more. They all speak Japanese. Yep, all the Sherpas are Japanese. The fraternity brothers thought the Japanese had been driven out of India by 1944 but apparently some remained under cover as Sherpas. The more prosaic explanation is that the only extras who looked Asian the producer could get at the price were Japanese, and to let them use Japanese was good enough for the Sherpa tongue.

There are condescending and racists asides by our heroes about the Sherpas on whom their lives depend.

The duo stumbled upon Abominable in his lair and the roof fell in and stunned him. Thus incapacitated they tied up this Gulliver and shipped back to the States for study in a refrigerated telephone booth. This was no Tardis.

They knew Abominable was about because it was alleged he had creature-napped a Sherpa woman, but that loose end it left flapping. Just one less Sherpa to make stupid remarks about.

Abominable descends into LAX, and like many travellers is consternated. Officials with clipboards appear, asking what is in the phone booth. Having seen, Dr Who in action, they are careful. If it be man, where is his visa and passport? If it is beast, where is the quarantine certificate? The officials cannot decide. Can we? This is the only interesting scene in the film, and much, much more could have been made of it. Is Abominable a man or a beast? What about the Twit in Chief?

The journalist has made a sensation of him as a man, whereas the good doctor refers to him as an animal. The officials are inclined to believe what they read in the ‘USA Today.’

The Murdoch press, as responsible as always.

The Murdoch press, as responsible as always.

Yep. Hard to believe, but if a journalist says Abominable is a man, maybe he is.

To resolve this conundrum, the officials send for an expert. Huh? An expert in what? A theologian perhaps? A talk-back radio shock jock? A fraternity brother, often accused of crossing the line between human and beast? Who?

Whatever this Doctor’s qualifications he arrives, and sits at a desk. No, he does not look at the subject but smokes cigarettes at the desk. That’s how we know he is a regular guy.

By this time, Abominable has had enough waiting in his cubicle and he tips it over and this breaks it open and off he goes to wreak havoc here and there. Women are his prey, though why and what his motivation is, no one bothers with. Maybe he wanted return fare?

At no time was any effort made to communicate with Abominable but maybe he only understood Nepalese and neither Japanese nor Hollywoodese. To keep him quiet before the phone booth was ready they just keep cracking him on the noggin.

In Lost Angeles the rampaging Abominable Man is declared NRA-bait and Bam! They get him. Too bad, but it had to be is the coda.

The one cliché absent from this hash is the comic relief. For that relief much thanks.

No one is credited for the part of the Abominable Man but the gossip is that it was Lock Martin, whose role as Gort was unforgettable and this one was unfortunate.

Late in the piece the ever reliable William Phipps enters and tries to eject some life and humanity into this script but even he fails.

This film is one of several B- creature features made by W. Lee Wilder, the older brother of Billy Wilder, who got all the cinematic genius in the family. Lee Wilder used a screen play written by his son Myles Wilder. Case closed. They say Lee Wilder made worse films, hard though that is to believe.

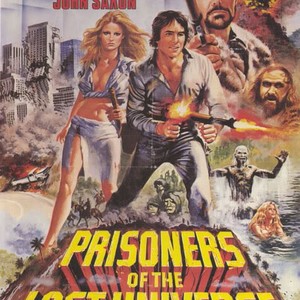

‘Prisoners of the Lost Universe’ (1983)

From the IMDB 3.7/10 from 878 votes, running 1 hour and 30 minutes Dali time. For a Sy Fyan this is a zero (0).

It comes up in searches for Sy Fy but it does not make the grade, but since I had to sit through it to discover this fact, I will give it a few words.

As crassly misleading as adertising must be, it seems.

As crassly misleading as adertising must be, it seems.

In 1983 contemporary Lost Angeles a blood sucker (journalist), a working stiff, and an uncle of Erich’s get transported to an ‘alternative universe.’ One at a time. Like the Three Stooges, each one makes the same mistake and gets transported through the photocopier. Pretty sure they did not go to Wonderland.

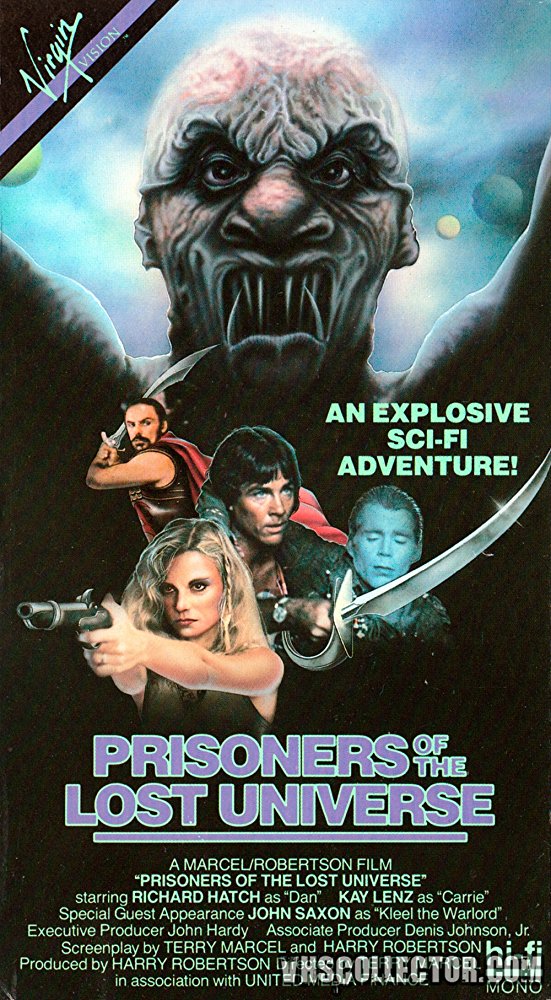

This poster pretty sums up the picture.

This poster pretty sums up the picture.

Once there Uncle is nowhere to be found, while Blood Sucker and Working Stiff stick together, ahem. Yet even afterward they still seem tense. The Fraternity Brothers found that odd, but then there were no cigarettes available.

After some roaming around they conclude that this is Disneyland with creeping thingies, hairy cave men, green elves, and more. This is a stone age world with spears, animal skins and furs for clothing. Altogether so primitive that the fraternity brothers felt right at home amid the grunts, thumbs, and beasties. They get into and out of scrapes and the time passed, slowly. S l o w l y,

The credits promised Carmine Orrico and so I persisted because if there anyone who can inject life into …, well, into a film it is Carmine. By the way the Hollywood gossip vine is full of strange stories about his life style choices. Even in Tinsel Town it is outré. He must have saved all his vices up for that because in this part as the Villain in Chief he looks bored, distracted, and worried (about his next doctor’s appointment). In equally limp offerings he has put some steel into the flaccid films. Not so here.

Uncle is working for Carmine as a wizard and Carmine makes sure his wizard does not find a way back to his own alternative universe.

Working Stiff is Richard Hatch from both versions of Battle Star Galatica with Sy Fy credentials, which also enticed me into viewing this swords and sandals bore.

Kay Lenz is Bloodsucker and she reminded me of Gretchen Corbett from ‘The Rockford Files,’ an old favourite. Doppelgänger one for the other they are, as a check for net pixes confirmed.

Most of it is out doors and though it starts with Lost Angeles, the whole thing was filmed in the Republic of South Africa of apartheid. When Bloodsucker is driving to meet Uncle at the outset the car radio is from LA and she drives not on the right, though the car is left-hand drive. The first hint that it was not filmed in the Alabama Hills, though that is the look, in a very dry summer. While the credits show many actors from the Republic I heard nothing I think of as a South African acccent. Still less did I see any black faces. Apartheid on the set, did not present a problem to the cast and crew, it seems.

The director also wrote the screenplay, served the tea, and must have many relatives to account for the few positive remarks in the User Reviews on the IMDb.

While Uncle refers to it as an alternative universe, in the marketing department this became ‘the Lost Universe.’ Of course, it is not lost to those who live there.

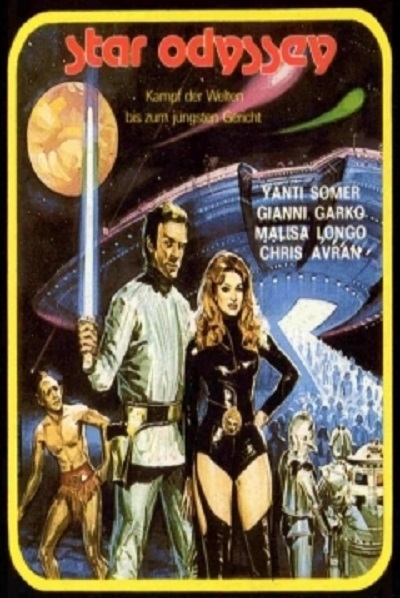

‘Sette uomini d’oro nello spazio’ or ‘Star Odyssey’ (1979)

1 hour 24 minutes of Dali time, rated 2.5/10 from 415 on the IMDB

In the effort to ride on the ticket sales of ‘Star Wars’ this quickie was rolled out, one of several Italian efforts of this kind. It is hard to get a rating as low as 2.5 on the IMDB.

It is, oh hum, another yarn about the end of the world. A mysterious spaceship appears from the void and penetrates all the many space defences Earth has, satellites, space stations, rhetoric, and an armanda are brushed aside. There is no reply to communication and atomic missiles bounce off.

There is only one thing to do in this crisis! Yes, project the Bat Signal into the night sky.

But wait, Batman took early retirement and is unavailable. Forget about, Robin. He was only ever there to hold the cape.

Instead High Command calls in Big Brain; Italian screen writers have an endless supply of bad tempered professors on call and Big Brain gets this part. He carries on like he is God’s gift to the world, while much of the world is destroyed. He rants on.

Later by some fancy screen writing the villain is defeated. The end.

At the end we learn the villain is a mega Meriton developer who bought the Earth at an auction to market its population as McKinsey KPI slaves. That might have been a better start.

The villain had some makeup! The fraternity brothers could not decide whether it was a road map of New Jersey projected onto his face or he was wearing the netting from last year’s Christmas ham, but he looked weird. In addition, his spaceship was overdue for service because it evidently has killer drafts, considering the triple high collar he wore on the back of his neck.

To subdue the Earth’s primitive inhabitants this bogey man dispatches an endless army of wig wearing androids, who when cut in half look like robots, but the characters insist on calling them androids. Droids or Bots, they all look alike to me.

The Earthlings fight them off with camera flashes. Honest, that is what it looked like. Luke also lent them a light sabre. Yes, indeed.

The decor of Big Brain’s house is all very stylish, I am told, but he never dirties his hands with any science, though some of the Z-team he assembles peer down lens and point at steaming vials.

There are also two or three robots brought onto the team who move like molasses and only bicker among themselves. These two would be an asset in any fight to save the world, not! Ditto the rest.

Though most of the film concerns assembling this team of Z-grade treacle, they prove ineffective against the Bogey Man and his wig-wearing automatons. As a last resort Big Brain wills the Bogey Man away. Wow!

Frontal lobes are creased in ominous and continuing silence. The Bogey Man relents. So that is what it takes to save the world. Wrinkle the frontal lobes and hang on.

There is also a lot of staring as coloured lights play on the irises of the one staring. If it was hypnotism it did not make the time pass any quicker, though we all hoped it would.

In contrast to some of the other Italian stallions in this stable of ‘Star Wars’ copies, the players in this one seem to be in on the joke and none try too hard to make it stick.

The title roughly means ‘Seven golden (hu)men(s) in space’ making this a variant of the Seven Samurai. Note the seven includes at least two women in this case. None of the characters is developed and none of their talents contribute to the defeat of Bogey Man. Figure that out. Why it appears in English as ‘Star Odyssey’ is anyone’s guess. It has also been marketed as ‘Prisoners of a Lost Universe’ but that may refer to the money put by the investors. It has been released under several other titles too trivial to list. But beware.

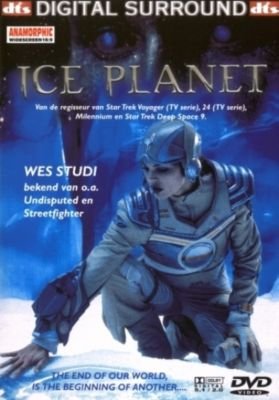

‘Ice Planet’ (2001)

A German production running 1 hour and 23 minutes, which rates 4.0 from 10 on the IMDB from 924 votes. Oh. My vote would be zero (0). The video quality is HD but the sound is not. It is replete with CGI and when they appear it is loud, while the dialogue is quiet. Up and down went the volume.

The plot? Good question, one I still have though I watched it. Some Earthlings on a space station get attacked and take off, ending up on the Ice Planet. It is a mixed bag of space cadets. travellers, research scientists, and odd balls. (Yes, really fresh-faced space cadets.) Now they have to work together to survive.

Sound familiar? Try Star Trek: Voyager, for one.

The players are the usual suspects. The martinet commander, the slinky woman, the bewildered astronomer, the square jawed cadet, the androgynous waif, and many disposable red shirts. The red shirts get toasted and roasted by a variety of mean CGIs. Boom, crash, wham! Perhaps forty minutes of the picture in all is a CGI mosh pit nonsense.

The visuals of the ice planet are neat but contribute nothing to the plot. They might just as well have landed in New Jersey for all the relevance it has.

A meeting with Ice natives made-up like Inuits is promising but dissipates into nothing. What I liked was the challenge of communicating without a language on the home turf of the Inuits.

Moreover, with their local knowledge they seemed like good allies, but no…..

Moreover, with their local knowledge they seemed like good allies, but no…..

Enigmatic or unintelligible, cryptic or vague, mysterious or incomprehensible, puzzling or impenetrable, full of ideas or indigestible, stimulating or half-baked? Those who gave it a 4.0 or higher on IMDb went for the former in each of the preceding pairs. Me, went for the latter in each case.

The IMDb has a plot summery that may have come from the press kit, because no one relying only on viewing the film would find it even that coherent. There seems to have been plenty of budget for CGIs but not for a continuity editor, and that adds to the confusion. The sound technician was AWOL.

Yet the director was Winrich Kolbe who has many credits from the Star Trek franchise. Many. Now that is a mystery. How did he come to make this…, hum, pastiche seems too elegant a term.

This was a movie-length pilot for a television series, and so we have something for which to be grateful. It was not continued. Reviewed elsewhere on this blog is ’Destination Space’ (1959) was likewise a pilot that failed but a far better exercise with some intellectual content and character development in a mere 41 minutes.

Much of it was filmed in Canada, and a web whisper is that Michael Ironside was in line for the captain’s chair if the series eventuated. Seems best this way.

‘Anno zero – Guerra nello spazio’ (1977) ‘War of the Planets’

2.9/10 from 617 brave souls but the zero (0) in the title seems to have application. It runs 1 hour and 29 minutes Dali time.

The only surprise here is that it is rated as high as 2.9 from 10. One of the many films trying to cash in on the success of ‘Star Wars’ but there is no comparison on any score. It looks like something from Poverty Row in the 1950s. The props look like leftovers from Flash Gordon of that era.

A strange signal disrupts all communication. That much is clear and that it about all that is.

The Italians launch a Ferrari space ship which traces the signal to an undiscovered planet somewhere. They need to clean the lenses on the telescopes more often to spot these things.

On this murky planet they find a giant juke box robot that has enslaved the humanoid locals with a GOP spiel and is now after the Earth! The plucky Italians in cute, colour coded skull caps set out to put things right amid incomprehensible cross-cuts, dialogue that sounds like out-takes from another film, a soundtrack that bears no relation to the action on the screen, until one of the crew takes off the skull cap and goes nuts. Guess that is why they keep them on. Prevents going nuts.

Proof? Did Silvio Berlusconi ever sport a skull cap? No. Is he nuts? Yes.

Most of it is so dark and so poorly photographed, who knows what is going on. The fraternity brothers made many rude remarks about this.

Our heroes, their numbers diminished in the dark, confront the juke box and talk it to death, and thus distracted, they then blow it up. At last!

Most of the cast and crew are Italians using English aliases, for reasons best known to the marketing department.

‘Il pianeta degli uomini spenti” or ‘The Battle of the Worlds’ (1961)

The IMDb info is this: 1 hour and 33 minutes of Dali time, rated at 4.3/10 by 563 ratings.

Long before Star Wars, the Italian cinema offered this title. Directed by Antonio Margheriti, who like others in the cast, used an Anglo pseudonym in the credits. In his case, it was Anthony Dawson. The aim was to sell the film into the American market, and along with the aliases, the director/producer recruited the Invisible Man Claude Rains for that purpose.

The set-up makes as much sense as some of the later Italian Sy Fy films. Z e r o.

Rains is a curmudgeon and at first I liked that but it went on and on and on. He lives in a palace by the seaside somewhere surrounded by bright young things. Easy to see why Rains liked the part for the three or four days he spent on it. Every one stands when he enters a room, and the bow their heads to him. Moreover the set abounds with sunshine, nubile and virile creatures coming and going, and no script to remember, just snarl.

Downstairs in his palace is a scientific establishment that by some unspecific means monitors the heavens. The fraternity brothers accomplish this with beer. How it is done in this seaside palace is less clear. Many bright scientists come and go; sometimes they enter Rains’s inner sanctum where they bow and hand him written reports in ring-binders. Furturistic, not. He looks disdainfully at their efforts, and in one case, while declaiming how useless the report is, an over the shoulder close-up shows he is holding it upside down. Well, it would not make much sense that way, would it. (Though I have tried that a few times with journal manuscripts I have had to review.)

He tells everyone how stupid they are repeatedly. He must be emeritus because he is never going to get another research grant with all the friends he is making.

Thanks to the Stockholm Syndrome, the more he abuses people. the more they think he is a genius. Why did not I try that in my career?

Then the Outsider, Planet X on loan from ‘The Man from Planet X,’ appears in the Solar System. Gulp! All eyes turn to Rains, who tells the eyes how stupid they are. See, he repeats the same line again and again. Easy to remember. He punctuates his castigations with cigar smoke.

High Command mobilises its Ferrari spaceships to blast Planet X. Rains tells them how stupid they are. Planet X will not collide with Earth, and only fools would think it would. However, it will pass so close that it will cause catastrophes of all sorts. This last fact does not bother Rains who is more interested in telling the others how stupid they are, while puffing away on his life-ending cigar.

Stock footage of catastrophes appears on cue. Floods, fires, short-order famines, hysterical people, GOP majorities, and stampeding animals, empty coffee cups and other signs of devastation. Rains tell everyone how stupid they are.

High Command sends the rockets to blast Planet X. Whoa! Flying saucers appear from the surface and blast the rockets. Game and set are lost. The Ferraris were a lot more show than go.

Rains tells everyone how stupid they are.

Planet X goes into orbit around Earth. Laws of physics go out the window. Whooska! Rains admits he had not foreseen this, but quickly recovers to tell everyone how stupid they are.

To prove his point he kneels on the floor and writes a few squiggles with chalk. High Command is so astounded that a man of seventy-two can kneel on the floor and get up that it gives in to his demands.

He claims as his own the discovery of an underling that the flying saucers go wobbly when hit with classical music. Phasers and atomic bombs have no effect, but a piano sonata does the trick. How much better it would have been had it been the Queen of the Night’s aria!

Rains tells everyone how stupid they are.

Rains tells everyone how stupid they are.

At seventy-two he takes rocket to Planet X, but at least this geriatric is not smoking a cigar in-flight. However he does tell everyone how stupid they are.

Sure enough the defending flying saucers go all dishy with the music allowing the Italians to land. Rains penetrates the interior to find THE TRUTH. Meanwhile, the landing party has started a giant doomsday bomb to blast Planet X into the void. (I held out hope this crescendo would be the Queen of the Night’s aria, but no.)

There are no inhabitants of Planet X and the flying saucers were automatons whose code was scrambled by the music. It seems an IOS update killed all the Xers long ago.

While telling everyone else how stupid they are, Rains ignores the calls to return to the rocket and leave before Kaboom. He stands around agape. Maybe he is wondering where his cigars are. No need because KABOOM! Now who is stupid?

The end.

That terse summary makes it sound better than it is. Watch at your own risk as they warn on CSPAN.

‘The Twonky’ (1953)

It runs 1 hour and 24 minutes and it seems like more. Four hundred and twenty-two opinionaters at the IMDb rate it 5.6/10 as of 3 December 2017. A generous lot they are, too.

It comes from the imagination of Arch Oboler, who did much television work, and it seems like an extended skit from a 1950s television variety show.

A hapless college professor, played by that television stalwart, Hans Conreid, buys a television, entering the analogue age with reluctance. This is a man who prefers to listen to Mozart while reading large and dusty tomes. I warmed to him right away. Not so the fraternity brothers who made a play for the remoter that had to be smacked down.

To please Wife, who finds him boring, and who would not, he buys the latest television, a device strange to him. It is delivered and left sitting in his study, it seems, while she is away.

Soon enough its true black-and-white colours show. It is Siri on steroids! A beam from the television knocks the second cup of coffee out of his hand. Not believing his eyes, Hapless tries again. Again a beam from the screen foils the caffeine intake. One cup, yes. Two cups, no.

Thereafter this TV Siri takes over. Its beam whirls records onto an off the turntable. Turns off lights when it thinks he should retire and so on. That beam is handy and it also vacuums the floor, answers the telephone, finishes Prof’s solitaire games, and prepares food. (However it does not mark the pile of student papers he carts around.) Wife being way, he suspects madness.

To get a witness he calls in his buddy, the ageing football coach whose playing days were well before the concussion protocol. Nonetheless, in time coach is also persuaded that the TV Siri is doing all these things. Even when it is not yet plugged in. Yep. No one has plugged it in or anything else and yet it is taking over. Did Marshall McLuhan see this film?

Twonky at work. Siri does not vacuum.

Twonky at work. Siri does not vacuum.

Efforts are made to return the television to the store. Foiled. To reason with it. Foiled. To cover it with a blanket. Foiled. To lock it in cupboard. Foiled. And so on, for forty-five minutes while Coach mumbles and Prof flicks dandruff off his collar, evidently a task Wife usually does.

Coach, after consulting his inner Erich, concludes this is a TV Siri from the future which has traveled back in time. What other explanation could there be?

This is the future that awaits us! A know-it-all Siri which will restrict our free will. It will light one cigarette for Prof but not a second. One a day is OK as with the coffee, but not two.

Prof gets even goofier than television profs usually are and embarrasses himself in front of a class. I kept looking at the clock, noting how slowly Dali time was passing.

Finally, this Siri TV is destroyed, by accident. Whew! Prof is free to drink more coffee and smoke more cigarettes.

Slight though it may seem, it is prescient because we now have our very own Twonky in Siri who can be programmed to ride herd on us.

Slight as it seems Arch Oboler always drives the points home with an axe. This is our future. Control and repression of our freedoms through technology! If so the film offers nothing about how to avoid this micro Nineteen Eight-Four future, but drink that second cup and smoke that second fag while one can.

Oboler’s best Sy Fy is ‘Five’ (1951) though it lacks the leaden humour of this film, it addresses serious subjects, so many that indigestion follows.

The term ‘twonky’ comes from the concussed coach and it means a MacGuffin, something that has no other name.

‘The Invisible Man’ (1933)

From the IMDB: 1 hour 11 minutes, 7.4/10 from 23,534,

Genre schizophrenia here. Is it a horror movie or is it Sy Fy? Arguments over definitions are best because they have no end, and no point.

H. G. Wells published the novel ‘The Invisible Man’ (1897) first as a magazine serial and then as a title. His hand makes it Sy Fy, but when Universal filmed it, that studio’s association evoked Horror because Universal had specialised in that genre. Though British in look, it was made in the USA.

The film differs from the book in several ways. The first and most important is that the Invisible Man is mad from the beginning on film, whereas in the book he becomes more and more unhinged the longer he stays invisible, which may be due to the drugs he is taking for the pain that the invisibility drug causes and the other drugs he is taking trying to become visible again. On top of that he takes strychnine as a pain killer. Killer, indeed. This guy could give the wanna be druggies around Kings Cross lessons in shooting up.

In the film his ambition from the get-go is a Reign of Terror, because he likes having power over others. In the book he comes to this term in his frustration to control the environment so he can concentrate on research to find a way back to visibility. He grows ever more unstable and despicable, but it is a process.

The film gives him a love interest absent from the book. She is played by a luminous Gloria Stuart who later appeared in ‘Titanic’ (1997) and whose last credit was in 2004. There was a sabbatical between 1946 and 1975. There are many familiars in the cast, and some familiar footage that was used again later in other Universal pictures, like the train crash.

While the Invisible Man causes as much mayhem as the fraternity brothers at the end of the semester in the book, in the film the Reign of Terror is not merely a threat, he kills at least two people, including his would-be confederate Dr Kemp. Moreover, he causes a train to crash with countless death and injuries. He is beyond redemption even by the love of good woman.

The book has some discussion of invisibility as a way of being. See! Sartre is relevant, albeit cryptic. (It takes him hundreds of pages to be cryptic. Nausea is certainly relevant to Sartre.) There is no doubt that Wells knew the references to the Ring of Gyges in Plato’s ‘Republic’ and in some way thought he was dramatising something of that philosophical discussion.

The fraternity brothers cut that class, and so for their benefit here is a refresher: Glaucon says a person is only moral because the responsibility imposed by society. Persons free of consequences of their actions would behave selfishly, knavishly, piggishly in the manner of the Tweet in Chief. If an ordinary Josephine came across a ring that could make one invisible, she would get up to no good. Want to know what Plato replied? Read the book! Wells’s novel is an examination of what an invisible person would then do. Though Dr Griffen, the Invisible Man, would hardly consider himself an ordinary chap.

At times I thought of the Invisible Man as an alter ego for Wells himself, and took the study to be autobiographical in a way. This is not a standard interpretation, so do not crib it.

The special effects must have been mind-numbing in 1933. Objects floating in the air, like a telephone. A cigarette smoking itself in mid-air. An unbuttoned shirt dancing by itself. The bicycle riding along sans rider. But most of all the several unveilings when the invisible man removes the bandages that conceal his nothingness. Did Jean-Paul Sartre see this film? Bet he did.

The Invisible Man unveils himself.

The Invisible Man unveils himself.

The denouement is the dealh of the Invisible Man, when the police cordon has finally tracked him down in the fresh snow and dealt him mortal injuries. His shoe prints were easy to track in the snow. Yes, shoe prints. But the shoes were not visible…

Lying in a hospital bed he gradually dissolves into view as the very young Claude Rains.

By the way, the cinematic invisibility of Claude Rains was achieved by wearing a black velvet body suit with no holes. None. Then putting the bandages on and then the clothes over the top. Altogether an uncomfortable and awkward business. Then he would be filmed against a matte, but the technical matters are best left to technicians. The point is that it was hard work being invisible on film just as invisibility was a curse to Griffin in the story.

Claude Rains was a young actor who had appeared in some silent films but who preferred the theatre and was content there. That is, until the Great Depression thinned theatre audiences to nearly nothing and income was hard to get. The Universal agent who negotiated the film rights with Wells agreed to an English lead and Rains, a near unknown then, was recruited. It was easy money for him and a free trip to the USA.

It made sense. A big name actor would be expensive and wasted since unseen until the very end in one shot. Indeed a big name actor might not wanted the part or demanded it be changed for more face time. Not even still photos before invisibility or flashbacks are used to show Griffin before. Plus the Invisible Man had to command the attention of the audience with his voice. Rains’s perfect diction and distinctive intonation did just that. He made it seem credible that he could dominate scene against visible actors where he was unseen, and so carry the audience with him.

Rains had done some screen tests earlier and they were terrible. He effected a declamatory style suited to nailing the back wall of a large theatre, entirely wrong for the camera, which magnifies everything. See Marshall McLuhan on hot and cold media for enlightenment, Mortimer. However his voice got the attention of the casting director and since he would not be seen, Rains’s emoting would not be seen. Moreover, the oral intensity of his emoting was in keeping with the Invisible Man’s madness.

In time, Rains liked earning a living in films and the sunshine, and adjusted his style to the camera. This story is a reminder of the differences between stage and film, and why some players prefer one to the other, and all find the change an effort.

Social invisibility has been a theme in literature and I expect somewhere there is a syllabus that brings some of it together. There is Fyodor Dostoevsky. ‘Notes from Underground’ (1864) and

Ralph Ellison, ‘The Invisible Man’ (1952). (Ross McDonald’s ‘The Underground Man’ is literally a man underground, buried.) Plus the other Universal films and their many imitators.