Those quaint English villages always scare me. First there was ‘Village of Damned’ (1960) and if that was not bad enough along came ‘Midsomer Murders’ (1997+). Thus alerted, when this title opened on a picturesque English countryside I feared the worst. and I was not disappointed.

Two pals do science, a lot of it. There is a tedious backstory first, but the chase is this. They invent a replicator that 3-D prints anything from energy not raw materials. They refer to making works of great art available by reproducing them and supplying rare drugs to hospitals. So far, so altruistic.

Then their prepubescent friend Lena reappears and, gulp, there has been much puberty. Scientist Robin marries Lena, leaving scientist Bill, who is a dopplegänger for Liam Neeson out in the cold, old shed where they have perfected the 3-D replicator.

Stephen Murray as Liam Neeson.

Stephen Murray as Liam Neeson.

Robin goes off to London to square the deal with Whitehall, while Bill mopes. A lot. Mopes some more.

Then, no doubt while thumbing though a copy of Mary Shelly’s most famous book, sets to work on improving the replicator to replicate…..Lena! Yep. It is quite a step from replicating a blank cheque to replicating a person but Bill does it. Much bubbling of liquids, flashing of lights, throbbing of boxes, muttering of incantations in the shed and the rabbits multiply. Next up Lena.

He talks her into it. He talks fast because this a short film. She agrees though why is by no means clear. Hey presto! Now we have the original Lena and the duplicate, Helen.

She is such a perfect duplicate this Helen that she, too, loves Robin, though he still in London. What is he doing there anyway when he has Barbara Payton back in the shed, chorused the fraternity brothers? Strange.

Bill has Helen but he does not have Helen. What to do? Ah ha! He will fine tune her in the shed. Not with roses and sweet words but with the mad scientist’s old friend, electricity! He will adjust the clone to erase her memories of Robin and start fresh with her. Lena, having come this far, agrees to assist so on a dark stormy night the three of them gather in the shed and strap Helen into the dental chair and set to work.

Kaboom! Too much juice and the contraption blows up like a Samsung Galaxy: Bill and one of the women perish in the fire. But which one? A nail biter that.

There is also the implication that the details of the replicator have also been lost in the fire and we will have to wait until the Twenty-First Century for 3-D printing. No more duplicate rabbits or Helens in the meantime.

Gosh, where to start. The ideal of reproducing at will objects from energy is to be found in much Sy Fy like Star Trek. But here no consideration at all is given to the consequences of doing so, though maybe that is why Robin got stuck in London. Some pedant there wanted to think about it. If gold is replicated in masses then its value will fall. If rare works of art become commonplace, they are no longer the rarities they were. If rare drugs proliferate like penicillin maybe diseases will mutate faster.

Still less is any thought given in the screenplay to the moral consequences of replicating a sex toy. Bill just assumes Helen will love him. He just assumes he will love her and not pine for the real thing. He just assumes no one will notice or question the uncanny resemblance of the two women.

Barbara Paton plays both Lena and Helen and she is indeed eye candy in the garish manner of the time. Never do we see any interaction between Lena and Helen, though each is aware of the other. That would have been too expensive to film for a quota quickie.

Payton at the time.

Payton at the time.

Payton was dead a few years later. The sex, drugs, and alcohol of Hollywood drove her to an early grave. She went to England to film this, it is implied in the Wikipedia entry, to escape these bad habits, but a few weeks in a facsimile English village and she could not wait to get back to Sin City. Once back there she reverted to her old ways.

Together with the robotic ‘The Perfect Woman’ (1949) and the retiring ‘Invisible Woman’ (1940) we certainly get the manners and mores of the times for women in Sy Fy. However in both these titles the women more than hold there own, not so here where Payton is little more than a Barbie doll.

It rates on IMDB 5.9 from 425.

Author: Michael W Jackson

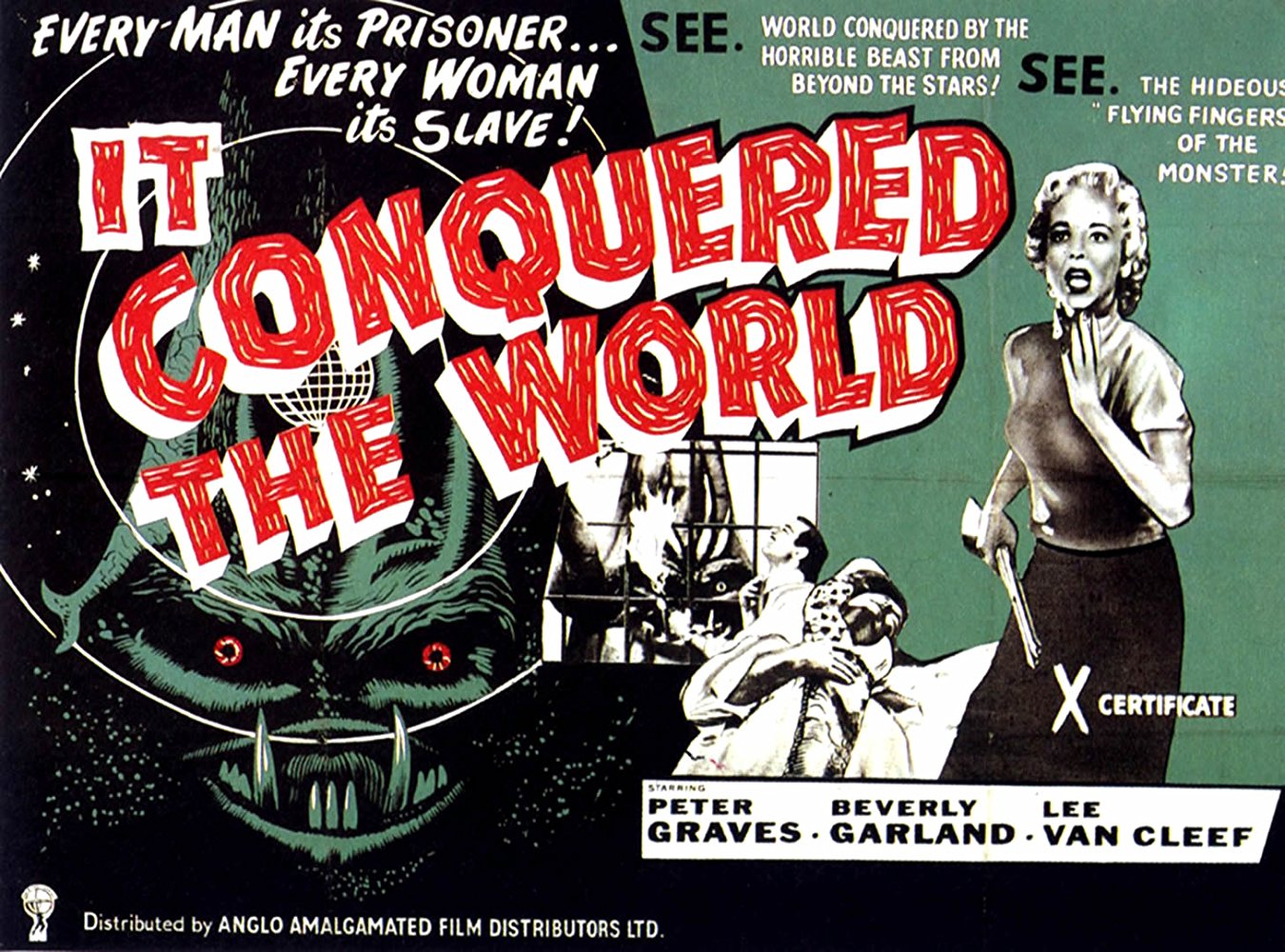

‘It Conquered the World’ (1956)

This early Roger Corman effort comes in at 4.8 over 1,618 votes on the IMDB. It runs 1 hour and 11 minutes.

What is the set-up? Buddies Peter Graves and Lee van Clef are doing science of some sort off camera in the desert southwest where most Sy Fy science seems to be done. Each has a wife with whom to play house. While the impossibly handsome Graves is very playful, van Clef with those beady eyes even at this early stage in his career has discovered the pleasure of (H)am_ateur Radio and talks to the stars, well no not his wife played by the redoubtable Beverly Garland who outlasted the man from Davanna in ‘Not of this Earth’ (1957), but to Zontar of Venus. Okay, so it is a planet and not a star for the pedants.

Zontar plays an old sweet song. He, well maybe Zontar is a she, gendering slime ball aliens is not in my pay grade, but Lee calls him a ‘he,’ Zontar, has travelled to Earth in Qantas economy class and is recovering strength from the rocket-lag of the trip in nearby cave motel. Been there.

Zontar promises Lee a heaven on earth for all humanity if only he is allowed to take over their souls. Seems a fair deal to Lee. After all Lola wanted a soul for a ball game, admittedly the stakes were higher there with the World Series. (Ray Walston had to go to Mars to escape Lola, but that is another story.) Zontar wants all souls, not just infielders.

In return for this Red Faustian bargain the reign of Zontar promises the peace and prosperity of slavery. No more wars. No more conflict. No more fights. No more pollution by green voters. No more tweets by twits. Please, no more ‘Top Gear’ I asked. Is this world communism, or what!?

Lee has no sales resistance and has bought the pitch and will do anything for Zontar in his blind alien-crush. He is the idealistic, weak-willed intellectual sort who would sell us out to the Enemies of Freedom so conspicuous in movies of the era. He is an enthusiastic fellow traveller. Amen. Meanwhile Zontar is mind-napping some local military types who are pushovers and Big Z wants Peter Graves, not for his chiseled chin, but because his scientific knowledge will help with the enslavement. It is a big world for one Zontar to conquer single-handedly but he is an ambitious red alien.

While Lee runs up the astral roaming phone bill talking to Zontar, his wife listens. She puts up with a lot as 1950s wives were supposed to do. She does protest when Lee kills some people at Zontar’s direction but relents when he gets all sweetness and light. Briefly. On it goes, back and forth. Zontar has brought a few trained bats in his checked baggage from Venus to transmit his mind control venom, but Graves fights them off. I left the room.

Graves’s wife however gets a hickey and becomes one of Them, a Zontar zombiette! Evidently there is no way back, and Graves with barely a moment’s hesitation shoots her dead with his handy NRA piece. Whoa! That was a surprise to this jaded viewer. Was that within the informal production code of the time? Shouldn’t he have socked her and tied her up for a later cure? On the other hand, there is no salvation for those who go Red. Better off dead.

Meanwhile, Zontar is running out of bats and orders Lee, who by now is so batty no bat is needed to infect him, to whack his old college roommate and buddy Peter. Lee pauses, briefly, before reaching for his rifle. All this NRA product placement has got to be seen to be appreciated. This is the last straw for Bevs, a registered Democrat, and she sets off to top Zontar herself with the last line, ‘I’ll see you in hell!’ (In that pithy phrase she sums up my reaction to ‘Top Gear.’)

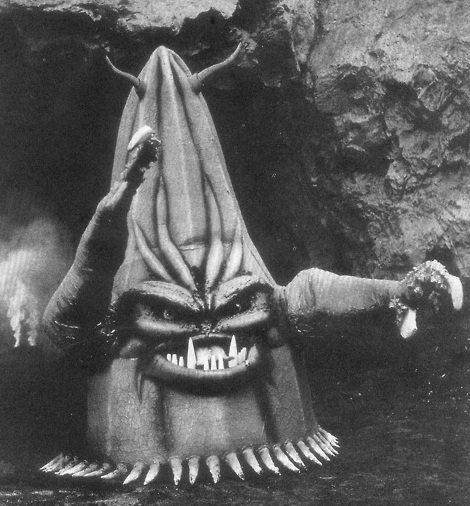

Zontar looks like a tall condom with tentacles. No one would notice him at Frat party.

See.

See.

This is one of many such creature features with Peter Graves, who was just too handsome to be a movie star. No one could take him seriously as an actor.

The masculine version of the Dumb Blonde, there for his looks. (I know the feeling.)

‘Zontar: The Thing from Venus’ (1966) remains to be seen. Keep watching this space for a report.

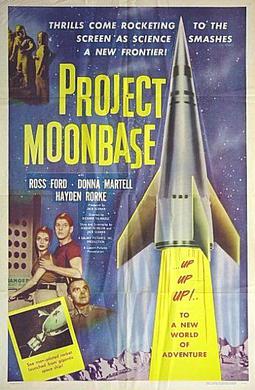

‘Project Moonbase’ or ‘Project Moon Base’ (1953)

1 hr 3 m @ 2.8/10.0 from 813 with nothing better to do on the IMDB.

He says ‘Project Moonbase’ and she says ‘Project Moon Base.’ Will they call the whole thing off? Nope. See below.

Never a good omen when the publicity department does not know the name of the film. The opening title on the film is ‘Project Moon Base’ but the lobby cards more often than not have it as ‘Project Moonbase.’

Two words

Two words

One word.

One word.

Schizophrenia goes deeper than the title and for that read on.

Many Sy Fy films of this era use aliens, consciously or unconsciously, as surrogates for communists with dark powers, malevolent purposes, and slavering tyranny. Whoops, starting to sound like the Twit-in-Chief. Sometimes that analogy is vague and in rare cases even absent.

Here it is front, centre, and explicit from the start in Robert Heinlein’s screenplay. The Enemies of Freedom (aka Commies) are no longer under the beds but under the launch pads of Yankee-doodle rockets. They have been there before in ‘Destination Moon’ (1951).

The Russkie spies in this yarn are dumb enough to sleep under the launch pads. They have an elaborate organisation that is run like General Motors with flunkies doing whatever it is that flunkies do and exact doubles for everyone in the space program so when a scientist is called into the Moonbase project, the Russkie tsar consults the space age 3″ x 5″ inch card file for the dopplegänger. Stupid, yes, but organised.

They off the scientist and insert their sleeper agent, who probably was — asleep — during agent training given how inept he proves to be at agenting. Not only does he know nothing about science, that could be overlooked, but more importantly he knows nothing about baseball and that is a dead giveaway. Although the crew is less than adept, too.

Paranoia is always a strand of Heinlein stories and it is the major theme here in this one. Another strand is that civilians are all stupid clots, and it is applied here with a sledge hammer key of the typewriter. Only men in uniform know what is what, though they seldom seem to know why is why. But as to the uniforms…well, seeing is believing.

There is a space race and the USA has a space station wheel from which will be launched the first mission to the moon to set up a Moon base as a peace-loving hydrogen bomb missile platform. Yep, it is that explicit. The general does say we had to include some science babble to get the funding, but it is will be ignored. Got it. That is democracy at work, lie and cheat.

The general then tells the putative leader of the mission to the Moon to stand down, because by presidential order the mission commander will be Colonel Bright Eyes. (Well that is what it sounded like to me.) Gasp! Those civilian fools in Washington interfering again in macho military business. This latter theme is another old faithful in Heinlein’s cosmology.

The general and the major agree that Bright Eyes is one giant pain in the rear echelon. Cue Bright Eyes to enter.

Whoa. Colonel Briteis is a woman. Gasp!

She leaves her shirt unbuttoned so as….

She leaves her shirt unbuttoned so as….

She gets to go because it is good publicity and she is half the weight of a man. Huh. Much was made in the opening that on the Space Station weight did not matter but now it does. Hulking Major Dimwit goes along as co-pilot to save the bacon later.

To make sure Colonel Bright Eyes knows her place, the General threatens to spank her. Yep, that is the military. Coercion and brutality are the order of the day. Later the major in a stirring display of military discipline tells the commanding Colonel to powder her nose. Later the general on the space radio sends Colonel Bright Eyes away for a private chat with Dimwit, thus abrogating the chain of command.

Meanwhile, the Russkies have planted that double as the civilian scientist. See, the civies can never be trusted. He sets about gumming up the works in the most obvious fashion possible, but Major Dimwit lives up to the sobriquet. Colonel Bright Eyes and Dimwit spar. (We all know how that will end.)

There is a rocket called Canada and another Mexico, but rest assured both bear USAF markings. They serve no purpose in the film but pad it out. There is a lot of padding to get a 25 minute film up to the 63-minutes that this is. Everyone walks very slowly. Slower. Slowest. The countdowns to launch are in real time. Zzzzzzz.

The scientist spy is Doctor Wernher whose name is spelled out three time for the dolts in the audience. Get it? Wernher von B….

The story published in 1948 gets some things right. A space station by 1970. Check. Well in 1971 Salyut 1. Oops, a Russkie. A lunar orbit for Discovery. Check. Apollo V in 1968. And that a special lunar landing craft would make the descent. Check. Apollo XI in 1969.

The stress of takeoff is well presented. The fight during takeoff with heavy gravity is an interesting idea, a slow motion struggle against the G-force and each other. The moonwalk is up to Michael Jackson standard. The wall walking and upside down meeting in the space station are contrived for effect and add nothing to the story or ambience. Moreover the general who was left on Earth pops up there in a tee shirt and beanie. It is easy to see why this general was demoted to a colonel on ‘I Dream of Jeannie.’

The Russkie agent is a klutz but Dimwit is just as bad when he rats out the Russkie to Colonel Bright Eyes well within earshot of the klutz. Loose lips. They then fight as above.

The sets are silly, the dialogue insipid, the acting robotic, the sexism suffocating, and the like. Then there are the Peter Pan hats and short-shorts as space wear, perhaps to reduce weight.

On weight, the general says no one sent up weighs more than 150 pounds yet earlier he said Dimwit weighed 180 pounds. See what can be learned by listening.

Silly, well consider this. Once they are stuck on the Moon high command calls it Moon Base (Moonbase) One. But with a young man and young woman in a tin can on the moon for weeks or more while a relief force is sent, it would look better in public opinion if they were married! Dimwit is reluctant. See, a dimwit. But Colonel Bright Eyes can hardly wait! She literally jumps at the chance! What all women want, even on the moon is to be married to a hulking hunk. Without courtship and in low gravity they get married. Think about that low gravity, because the fraternity brothers did.

It is worth watching to the very end. Because after they are married up there on Moon Base One the President of the United States appears on the space videophone, and it HILLARY CLINTON. Yes, a woman in the White Hosue by 1970 according to Heinlein.

And Major Dimwit is promoted to general to outrank his colonel wife. The end.

The deeper schizophrenia of the film per ‘SciFist’ is this. The production was commissioned for a ten-part television series with the budget and cast for that. Heinlein’s story and screen play were adapted for that purpose. In pre-production (preparing wardrobe, renting space and equipment, gathering cardboard props, hiring extras, and so on) the studio changed it to a B feature film. Why? Because the success of other Sy Fy films offered an opportunity to ride the coattails of those successes. By this time Heinlein was paid off and gone. The director agreed to add to the script with the result we see. The budget did not change nor the casting. Walking slowly was one way to pad it out to feature length.

The essential difference is that in the original the first episode would be an exploratory orbit of the moon, and in subsequent episodes there would be a landing. In the film the lunar lander crash lands because of the fight with the enemy of freedom agent.

Strangely, along with ‘Destination Moon’ (1950) this was the last movie form Heinlein’s work until ‘Starship Trooper’ (1997). Odd that.

In mentioning props above, I should have noted that the space suits used are the very well used ones first made for ‘Destination Moon’ (1951) but here they have different helmets. They also figured in ‘Flight to Mars’ (1951).

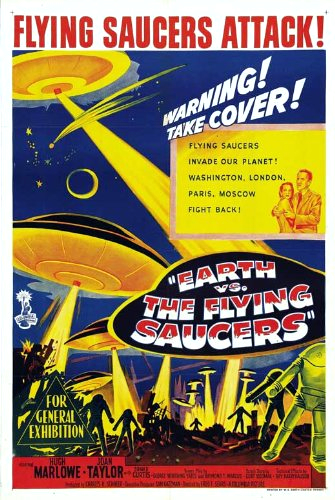

‘Earth vs the Flying Saucers” (1956)

One of the high water marks for 1950s Sy Fy, subspecies flying saucers, phylum alien invasion.

Hugh Marlowe carries the movie in nearly every scene. He was a sceptic about aliens in ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ (1951) but he is persuaded, slowly, in this 83 minute excursion. He is ably supported by Joan Taylor and Sy Fy stalwart Morris Ankrum. The special effects were quite special in the day and remain compelling.

Marlowe is the lead scientist and the decision maker in Project Skyhook located in the desert southwest. Where else? While driving along with his newly married wife he dictates the latest report on the project which involves launching a dozen satellites to scan the heavens. Then…..

A weather balloon appears behind their car and buzzes it. Zounds! Some weather balloon! Yes, Erich, it is a flying saucer for what other explanation could there be given the title above.

Hugh, remembering his journalistic skepticism earlier, will only admit to Joan that they have seen something that looked like a, ahem, a…flying saucer. This scientist is not leaping to tweet the sighting but sitting on scholastic dignity. Joan is incredulous because she knows very well what she and they saw. In all it is a nicely done in-joke about those who doubt their own eyes.

It is also the pivot of the plot, but that emerges only later in a spoiler below.

They report the sighting to Morris at Skyhook who is skeptical but indulgent.

It turns out the Skyhook satellites disappear as soon as launched. Is there a connection between the what-appeared-to-be-a-flying-saucer and these disappearances. Hmmm. Then one of the saucers lands at Skyhook and the doubts and many of the doubters vanish in a cloud of atoms.

Two tin men emerge from the saucer and Morris immediately opens fire on them with an anti-aircraft gun he keeps nearby, killing two of them. This greeting is reciprocated with a disappearing ray that disappears a good number of grunts. The saucer then destroys the whole facility for good measure. Thanks to the script Hugh and Joan survive and lead the response.

Response? Well there is no denying that the Skyhook base has been levelled and hundreds killed, leaving no eyewitness left alive. While the taxpayers money was being burned, Hugh and Joan were sequestered in an underground bunker canoodling and only glimpsed part of the destruction on closed circuit television. There were no tapes. Just their assertions.

The batteries on the tape recorder Hugh was dictating into during the drive get low and that slows the playback of the recording reel where they hear a strange voice proposing to meet at Skyhook tomorrow! Next time, High, check the voice mail sooner! Had he done so earlier the destruction could have been avoided. No wonder his reception in D.C. is frosty. The project he managed is gone. His Key Performance Indicators are zero. Minus even.

The Pentagon panel to which they report is stacked with faces from 1950s television and they are no push overs for wild assertions about flying saucers because they have heard it all before on ‘Perry Mason.’ They listen to the odd message but doubt its relevance, authenticity, and its Euro Vision potential. Still they do know something is up. Just look. Flying saucers are crowding the airspace. O’Hare is even more chaotic than usual.

Hugh calls the aliens on the interplanetary radio he happens to have in his D.C. hotel room and makes another date.

Get this and get is straight! The alien asylum seekers called Hugh and made an appointment. They showed up at the right time, at the right place to be blasted by a 75 millimetres cannon. Bam! Bam! Two dead. Not a good start. The American Earthlings were the aggressors! Gulp. There goes the moral high ground.

Since blasting Skyhook in retaliation to the massacre of their two defenceless asylum seekers, the aliens have been busy. They apprehended Morris and have scanned his brain for intel. (Too bad they didn’t get Pat Robertson. Please!)

They now know enough to compete on ‘Eggheads.’ Many viewers long suspected Morris knew a lot more than he was saying.

It turns out the aliens’ plan all along was to conquer Earth! Ah, the moral high ground is restored. What appeared to be an aggressive and gratuitous assault on the alien landing party was a preemptive strike. Maybe the moral ground is more a hillock.

The aliens tell Hugh they had hoped to negotiate an accommodation, having done that elsewhere. Well there are always those parts of the Earth not fit for human habitation, e.g., the Gobi Desert, New Jersey, Mormonland, Trumpville, and the WestConnex wastelands of Australia. But no, we human do not compromise with asylum seekers.

While the military’s weapons bounce off them the saucers, like evidence off an anti-vaxxer, they wreak havoc with special effects on D.C.

The saucers destroy the Trump Hotel (the Old Post Office) to cheers from a nearby sofa. Meanwhile super nerd Hugh has come up with a film producer’s dream weapon, wired together from junk, firing an invisible ray, and inaudible sound wave that drives the flying saucers away! And it cost next to nothing to assemble or use. It is one step up from pointing am index finger and say ‘Pow!’

Whew!

There are many visuals of flying saucers, a lot in a prologue that to my mind spoils some of the drama to come. The destruction of scale models of Washington D.C, is well done. Loved seeing the Washington Monument fall on a gathering of Tea Party acolytes denying flying saucer change.

The saucers leave but will they return? Will there be a sequel? We are still waiting on that one.

Made at the height of the Cold War there is no doubt that the aliens are surrogate commies with a nefarious plot. When things go wrong, it is the commies’ doing, even if it is not apparent. And they will stop at nothing, including brainwashing scans. Moreover, when they talk at Yalta their plans are already laid for conquest. Get it?

The United States is leader of the world and has to go it alone. There are only perfunctory references to the rest of the world.

While the military is ready with atomic bombs it does not seem a good idea to use one on D.C., though today some might differ.

Hugh had some extra-planetary experience earlier in ‘Worlds without End’ (1956) and he puts it to good use in this movie. Later he played Rush Limbaugh in ‘Seven Days in May’ (1964).

Ray Harryhausen did the special effects from a story by Kurt (sometimes Curt) Siodmak. The incidents and the visuals became touchstones in the subsequent Sy Fy films like ‘Mars Attack!’ (1996). The direction is crisp and the pseudo-science is mucho pseudo

The asylum seeking aliens are enigmatic in their wardrobe and even more so when uncovered.

I saw it on the widescreen in Lexington Kentucky with cousin Don in 1957, and it stayed with me.

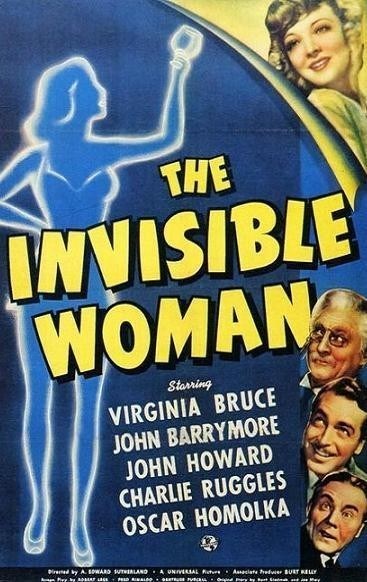

‘The Invisible Woman’ (1940)

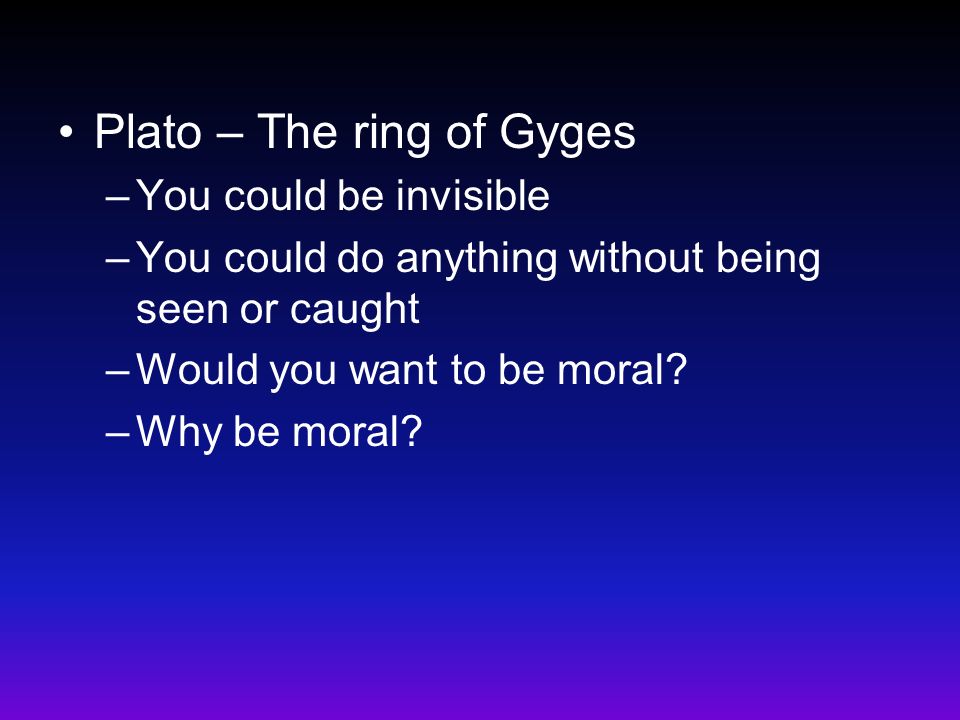

Sy fy but only just, and played for laughs. First there was The Invisible Man’ (1933) and after his return there was the invisible woman. For Plato’s perspective read on.

A lobby card.

A lobby card.

Universal Studios secured the agreement of H. G. Wells to make five films using the invisible man, and this is the third of them. It would be churlish to point out an invisible woman is not an invisible man, the more so when s/he cannot be seen.

Seen or not, here we have a female lead in Virginia Bruce who makes the most of it. Some very costly special effects for the invisibility combine with some stock characters, the absent minded professor who started the whole thing, the cantankerous house keeper, the playboy financier, and Charlie Ruggles as the long-suffering butler. Then there are the villains who want to steal the secret of invisibility and offer more slapstick in their effort to do so, one being Shemp Howard. Say no more.

The stocking scene was a shocker at the time.

The Sy Fy element is a combination of flashing lights, sizzling electricity, and an injection of invisibility serum to activate it all. Alcohol has a deleterious effect on the process. The story is credited to Sy Fy great Kurt Siodmak.

Bruce is a hard working mannequin desperate to keep the pitiful job, bossed around by a petty tyrant. When the professor advertises for a subject to become invisible, among the applications from Christian zealots is her letter. There is no pay, only, say, three hours of invisibility. She jumps at the chance. Her motivation in taking the risk of invisibility is to terrorise the boss at work. She uses the first period of invisibility to do so and he changes his ways thereafter. If only.

What could, should, or would one do if invisible is a question to conjure but no conjuring is done here. On this latter point more below.

Thereafter is much comedy about clothing, which cannot be made invisible. Some of it is funny and all of it is harmless. The villains trip over each other and ham it up something terrible. Oscar Homolka’s eyebrows are positively feral.

Bruce is not the typical retiring silver screen maiden of the era when she literally kicks ass, slugs down booze, straightens out the playboy, and flattens the villains single-handedly. This is all done with élan. Ruggles as the fainting butler handles the duties often given to leading ladies of the era.

The playboy falls in love with this wonder woman and they all live happily ever after.

Bruce of Fargo North Dakota was a student at UCLA and worked as a film extra for the readies and one job lead to another. She was also a voice actor on radio and that talent is well used in this film. She appeared in a few A-pictures as the second female lead, but mostly did B work like this title. When I scanned the list of her credits on the IMDB nothing stood out. This title rates there 6.1 from 1,441 opinionators.

In Book II of Plato’s ‘Republic’ is a discussion of the Ring of Gyges. The Ring, when the bezel is turned just so, renders the wearer invisible. Glaucon, brother of Plato, suggests that given such a ring, a normal person would become immoral because the invisible person is then freed of the social repercussions of one’s actions. Instead an invisible man would perv at naked women, steal, injure or murder rivals, and perv some more. Sounds like the Channel 7Mate demographic. Or Christian zealots.

Socrates replies anyone who is virtuous only due to the constraints of social consequences is not virtuous to begin with.

When Wells wrote ‘The Invisible Man’ (1897) he was well aware of this discussion in Plato. Other genre writers have riffed on Wells’s take on invisibility ever since. The one at hand is Robert Silverberg’s 1963 story ‘To See the Invisible Man’ in which a future society makes invisibility the punishment for certain crimes. The story considers the social and psychological effects of such treatment.

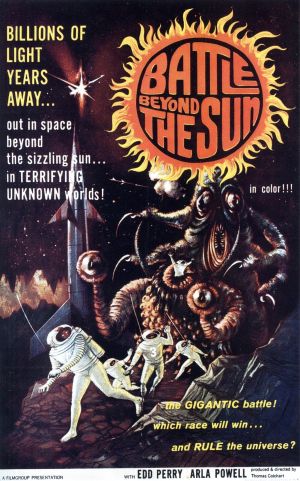

‘Battle Beyond the Sun’ (1959)

‘No battle and little sun, but two for the endurance of one.’ That is the tag line that applies to this 1hr 17 minutes exercise. On the IMDB it is titled ‘The Sky Calls’ (1959) yet the art work proclaims the title ‘Battle Beyond the Sun.’ Go figure.

It was made in the Soviet Union a short while after the launch of the first Terra satellite, Sputnik, in October 1957 as the threshold of space flight was crossed. In some shots it shows something of Star City where the Soviet space program developed and the displays of weightlessness are good. These effects are several cuts above the norm at the time. However the space flight effects are at the norm, e.g., flames in the void of space.

Two for one? There is the original Soviet version and another. In the first version the Soviets with rockets clearly marked CCCP have an orbiting space station devoted to celestial science and are methodically preparing a peace-loving mission to Mars. Then out of the void a US rocket calls for permission to dock and repair engines. The Soviets graciously agree. Though the interaction is constrained, the sneaky Americans learn that the Soviets are Mars-bound.

The Americans rush back to their ship and blast off for Mars in the hope of getting there first and claiming all the Mars Bars for Yankeeland. In the haste, the back draft of their rocket injures a hapless Soviet crewmen star-bathing on the deck of the space station. He is long suffering and very forgiving.

In due course the Soviets take off for Mars and no sooner do they do so than the impetuous Americans run into trouble and SOS to the Soviets, who divert from the Mars course to rescue them, and in so doing they expend most of the fuel. Gulp!

Both crews are only two man, one a retiree and the other younger, both clad in polyester knits. Remember those? If not, lucky you.

Both rockets were built for a two-man crew, right, but somehow the two American passengers squeeze on board into the micro-economy seats. The Soviets decide to land on a convenient asteroid and send for road side assistance. They borrow a dime from ET and call home. An automatic, pilotless fuel tanker is dispatched to the asteroid. It is no recommendation for Tesla self-driving cars that the fuel tanker crashes into the far side of asteroid. Gulp!

It seems the asteroid is too hard to hit for a computer so a second pilotless fuel tanker rocket is sent with a volunteer pilot. How he squeezed in is left to the imagination. The fraternity brothers imagined the worst.

He pilots the rocket to the asteroid and lands. The stranded spacemen do not seem to notice, so busy are they in trading clichés about cooperation and peace. Zzzzzzzzzzzz.

The tanker pilot of the once-pilotless ship becomes sick from radiation poisoning since the pilotless fuel tank rocket had no shielding to protect the pilot. Did anyone tell him? Is there workers compensation? What are the KPIs here? Did the manager manage? The sick pilot roams around the asteroid and dies. The maroonies find the dead man and realise he came by rocket. They are scientists after all and they can make inferences. Zounds! They tank up and blast off for Terra to carry the clichés back. The end. Then the dreamer awakes and it was all a dream. The double end.

Wait! There is more!

Roger Corman bought the film and edited it for the US market in 1962. He hired a destitute film school student to do the work and credited him as associate producer, that was Francis Ford Coppola’s first on-screen credit. He took liberties in the Corman manner.

All references to the the CCCP and the USA are obliterated by kindergarten finger-painted blobs of colour. A voice over prologue says the following story takes places after an atomic war and it is a race to Mars between the Northern Hemisphere and the Southern Hemisphere, the two Orwellian blocs that emerged from the rubles. (Joke.) The dialogue was cleansed of the anti-American references or mentions of the Soviet Union. The dubbing is as annoying as it usually is. The nylon double knits remain, as do the geriatric Soviet actors who move with glacial speed. It is set in 1997 and, despite the insertions, is shorter than the ponderous Soviet original. Mercy be. It remains ponderous.

Knowing the market, Coppola also exercised artistic license to insert a scene on the asteroid while the dying tanker pilot wanders around, in which scene he observes two proto-CGI creatures fighting each other. This scene qualified the movie to go on a double-bill of creature features, and the fight has nothing to do with the story and is never mentioned by any of the survivors. Accordingly they do not warn future travellers not to stop there. They bad. Thus launched was FFC’s film career.

In the end, the rocketeers watch red Mars in the near distance as they blast off for home.

Yes, they have their clichés safely on board. This is no dream.

But to watch it is to see, Braque-style, two movies in one. The original Soviet snooze and the Corman mash-up.

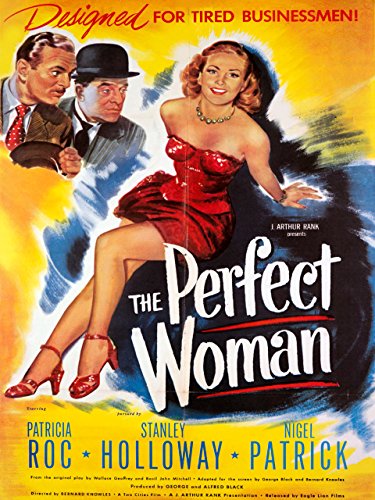

‘The Perfect Woman’ (1949)

An emeritus professor played to a T by Miles Malleson — described as the lord of Brit screen eccentrics — wants to demonstrate conclusively to skeptical colleagues that he has mastered robotics by presenting The Perfect Woman to them. Before exposing his creation to the doubting Thomases the Prof wants the Perfect Woman road tested, and hires a ne’er-do-well who, like all the best cinema ne’er-do-wells has a butler at hand.

In the comings and goings at the Prof’s house and laboratory his niece insinuates herself into the proceedings and the ne’er do well mistakes her for the robot he is to escort around. (‘Quiet down, Fraternity Brothers!’ ‘Stop that snickering!’) She plays along for laughs. The sight gags are many, as is the word play as Ne’er and his butler read aloud the user’s manual for the robot to learn the voice commands. ‘Siri!’

Inspection of the robot with manual.

Inspection of the robot with manual.

From this set up it descends into a genteel bedroom farce, rather than a rumination of what it means to be human or for that matter to be a robot. There are no laws of robotics here. While the pace dragged a little early, in the last reel it rattles along and ends with a bang.

The rattling offers the stereotypes and conventions of the time and place. The Perfect Woman does exactly as she is told, has no will, does not eat or sleep, does all woman’s work without a word, and stands mute. Just what a 1949 chap wants in bride, and Ne’er is smitten. Screened in a gender studies class today, it would confirm much of the syllabus. Screened on Channel 7Mate and it would fit right in.

Truth will out and in the aftermath they lived happily ever after.

All the players ham it up and the energy is good in the latter half, including a ride on the tube with the robot. Patricia Roc is top billed and carries the picture with her sly looks, inner smiles, blank stares, and mischief. Likewise the robot Olga is played perfectly, too.

A production still that shows how hard it is to be intimate on film.

A production still that shows how hard it is to be intimate on film.

By the way, this was a major production with well known actors, extravagant sets, many extras to fill the screen, and plenty of cameras, very unlike the Quota Quickies that dominated Brit Sy Fy at the time.

Not something I would ordinarily have selected but I noticed it on SciFist, an excellent blog about the history of science fiction films, and looked for it thereafter. It is a 6.0 from a paltry 107 votes on IMDB.

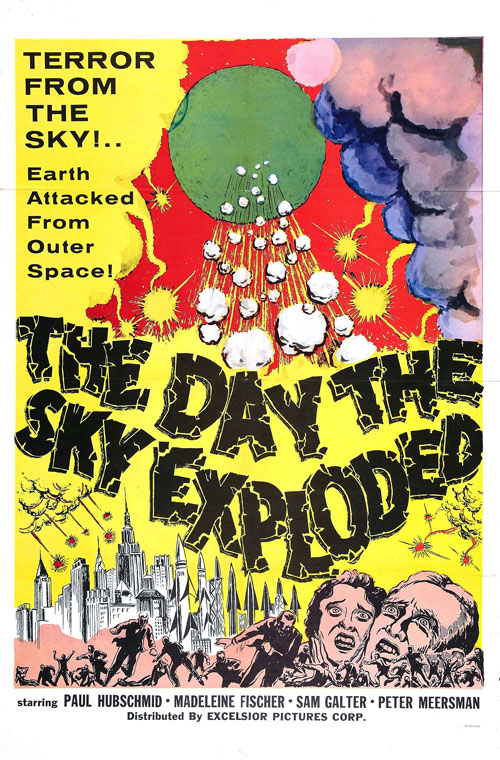

‘The Day the Sky Exploded’ (1958)

The data: 1 hr 22 m at 4.3 from 481 opinionators on the IMDB

Lobby card.

Lobby card.

Paul Hubschmid, Switzerland’s best known movie star, plays a fearless spaceman riding the first rocket to the stars from Cape Shark in FNQ, that is, Far North Queensland to the shoe-wearing southerners. Whoa, ‘Switzerland’s best known movie star,’ some of the weberati say, but the fraternity brothers demur, remembering that scene in ‘Dr No’ (1962), they cried Switzerland’s best known movie star is Ursula Andress.

That Paul is Switzerland’s biggest movie star is uncontested. At 6 feet and 4 inches plus he looks like a small alp among the cast in this Sy Fy yarn. How did they get him into that rocket. He looks bigger than it does in some shots (and he certainly was because it was table top model).

The alp that is Paul.

The alp that is Paul.

HIs bold launch is acted out with a micro budget and a lot of wire. The main prop is a crash helmet borrowed from Ro-Man. Throughout the film is padded with stock footage of airplanes landing, airplanes taking off, more airplanes landing, animals rampaging, football fans rioting, crowds crowding, managers managing, and close listeners will hear the same laments in the background a dozen times as the tape loops.

Though made in the deep freeze of the Cold War it is international and ecumenical, quite unlike most other productions of the time. In that sense it is hopeful and optimistic. It does not use space as a metaphor for dealing with commies. Rather it starts with the Franco-Italian production company and continues in the cast which includes Swiss, Brazilian, German, French, Russian, and Italian names. No Brit or American though it was clearly made with those markets in mind, hence the Australian setting (in an Italian sound studio), which, by the way, for a film of the time was extraordinary. There is no Cape Shark in FNQ but there is a Cape York and at times Queensland governments anxious to distract voters from reality promote Cape York as a spaceport, perhaps because Joh Bjelke-Petersen, long time Czar of the North, saw this movie and got the idea; Richard Branson has even had a look. What he saw was the traditional aboriginal owners who showed no interest in a spaceport. If and when Branson flashes that big smile and that even bigger bank roll they may see the stars, but not just yet.

The space mission portrayed in the film includes Russians! Yes, all nations are cooperating in this fictional 1958. Many chefs spoiled the stew because the mission cocks up. After launch the controls on the spacecraft seize up, probably during an IOS update, and Paul bails out. Bails out from space.

I blinked and missed the detail but he bailed out and returned to Earth leaving the rocket to plow on into deep(er) space. He did not, he claimed that he was unable to, set the auto-destruct. One measly button and he forgot to push it, probably ogling a picture of Switzerland’s best known movie star when he should have been watching the dials. That is what the fraternity brothers thought, judging from the guilty look on his face. The rocket with its 1958 atomic reactor engine retrofitted from the Nautilus is left to fly on. There are some recriminations about this oversight of the ‘I thought you did it’ kind with ground control. Key Performance Indicators are brandished. Then all is forgiven.

Georg Hegel once said that nature always wins. (It took him nearly a whole 500-page book to say that.) In this case the rocket blows up in space and that explosion throws a giant meteor onto a collision course with Earth!

See, exploding sky. If it is missed the first time, it is repeated twice more.

See, exploding sky. If it is missed the first time, it is repeated twice more.

That turn of events occasions much footage of scientists making presentations to each other about the forthcoming catastrophe, talking heads explaining planetary extinction to each other, and breathless journalists trying to get a last exclusive onto their obituary CVs. Meanwhile animals stampede, crowds lament, and women cry in the recycled stock footage. I left the room while the padding played on.

There are sub-plots. There is a young woman referred to as a mathematician who inputs data into the calculator, which is sometimes called a computer on other pages of the script, and the man who wonders if being smart is not unnatural for a woman. Being smart was not a burden for him.

Paul has a wife and child and occasionally they appear only for him to say he is too busy saving the world to see them. The icicles between Paul and the Brazilian playing his wife lowered the room temperature at our place. ‘No rapport’ does not convey it, more like an open hostility that did not bode well for Swiss and Brazilian relations. Proof? Well look at Brasilia. Are there any alps there? See! Case closed.

As DOOM approaches, one of the German scientists goes nuts. He turns off the air conditioning and in FNQ that is a capital offence and goes around shooting people with his NRA-approved Lugar which is only a misdemeanour there. For once the Swiss stand up to the Germans and Paul knocks him into a Mars orbit.

Then Paul, having flexed some of his many muscles, has the bright idea of having all nations, and I mean all, fire their entire armoury of nuclear armed missiles at the meteor and blow it into meteor dust. The list of nations with nuclear armed rockets includes Japan, Australia, Netherlands, India, USA, Denmark, Texas, USSR, France, England, San Marino, Andorra, but strangely not North Korea, Israel, or Iran.

It works. The end. Ahem, the science correspondent on the sofa thought the ensuing meteor dust would blanket the Earth and end any further career openings for Switzerland’s biggest movie star.

Was Brazil dropped from the list of nuclear armed nations, is that why Paul’s wife is so angry? Did she forget to iron his shoe laces, is that why he is so reluctant to go anywhere near her? Kevin may know, but I do not.

The version we watched was dubbed for release Stateside in 1960 and some spinning newspaper headlines referring to JFK were inserted to connect with that. The variety of accents from the polyglot cast of dubbers was good but we wondered about the Strine drawl of the 1960 Australians for that was a time when the BBC accent was a Down Under thespian requirement. Still there it is.

As I watched Big Paul tower over the others, I wondered was it in his contract that no one in the cast could be as tall? Then I realised that I recognised him. He was Johnny Vulkan in ‘Funeral in Berlin’ (1966) with the white Cadillac convertible tooling around West Berlin.

By the way he had an earlier film career in Berlin working for Dr Goebbels in Nazi Germany with small parts in about a dozen of light-weight entertainments that the Evil Dr used to distract people from reality. This was no bar to Paul making a few movies in Hollywood, including several as the male lead with a major star like Debra Paget.

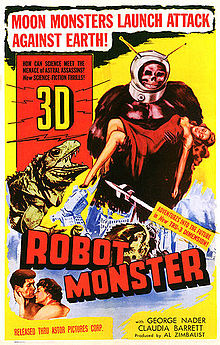

‘Robot Monster’ (1953)

Fresh from ‘Cat-Women of the Moon,’ Al Zimbalist cranked this one out. Some facts first, it runs for 66 minutes and scores 2.9 from 3,772 rankings on the IMDB. It is often cited as a leader in the category of It’s-so-bad-it-is-good. It certainly is bad. By comparison ‘Cat-Women of the Moon’ is sophisticated cinematography.

Yet ‘Robot Monster’ is distinctive in the creature feature annuals for one very important reason. The creature – Ro-Man, as he sometimes styles himself – has a soul and it shows. Keep that in mind for later. Did The Blob have a soul? No! Did the Creature from the Black Lagoon have a soul? No! Do Republicans have a soul? But Ro-Man does! Compared to these other creatures he has a spiritual quality.

The set-up is loopy to be sure. Bang. The Robot Monsters have killed all Earthlings but seven or is it eight. The count changes through the movie. (In addition, in one scene a passer-by strolls along the back of a shot. Is she in the count or not?) At least two of the survivors mentioned are never seen. Then there is a garrison in the space station who seem to be sitting out the apocalypse and do not figure in the count.

A Robot Monster has been sent to find and kill the last remaining aboriginals so that the Earth can be colonised as Terra nullius. Take that, White Man! With that Key Performance Indicator in mind Ro-Man gets right to work with a billion bubble blowing machine and television screen transmitter. These survivors are a family of two adults, three children, and the elder daughter’s boyfriend, played by George Nader on whom more in a minute. The budget is so small it does not run to a shirt for Nader in most scenes.

The players try to make something of the script, and fail. The two younger children are annoying enough to invoke the curse of W. C. Fields. It was a relief when the heartless Ro-Man killed them. Yes, for despite the unofficial and all the more stultifying Hollywood code at the time, Ro-Man strangles the children, to the cheers of the fraternity brothers.

The code did not allow for children to be murdered. They could die, disease, war, accidents, but not be murdered, kind a reverse spin on the current NRA approach. The code was not rigorously imposed on B pictures which is why they are often racier than their A picture peers, as known to all fraternity brothers.

Ro-Man’s HQ is a cave in a rocky desert with the bubble blowing machine and the intergalatic portable TV. This is the best he could do for real estate, this superior alien being? A cave? Take about low rent!

What a dump!

What makes ‘Robert Monster’ singular is that Ro-Man goes all Frankenstein’s monster and wants Alice, the older daughter, to love him, after he has murdered her husband, and her siblings and is about to murder her parents. In fact, he seems to ask her to sit tight while he goes off to murder her parents. Is this a sensitive New Age alien in the making? He refuses to murder her, and goes into a Hamlet soliloquy:

‘We are not built to feel emotion. Please do not hate me. Yes! To be like the Hu-man! To laugh! Feel! Want! Why are these things not in the plan? I must, yet I cannot! How do you calculate that?! At what point on the graph do ‘must’ and ‘cannot’ meet? Yet I cannot … but I must!’

Move over Shakespeare! Here are words.

This is deep thinking for a man in an ape suit with a fish bowl on his head. That is Ro-Man. The back story goes that the producer had a robot in mind but could not find one available at his price, and found the expense of having one made beyond the small-change budget, but he knew a fellow who once worked vaudeville in an ape suit! Voilà! But the titles had all ready been run and there was no budget to do them again, so… The fish tank went on to complete the ensemble.

Nader was her boyfriend but somewhere along the way, they got married, and went off on their own for honeymoon during the apocalypse. Believe it or not. While canoodling away from the protective shield of the family home (which does not seem to have a roof but has some kind of electronic barrier), Ro-Man finds them, throws Nader off a cliff to his death and ravishes Alice. It is all very Channel 7Mate.

Robot Man is the furriest robot ever filmed, and could be mistaken for Yeti except for the Newtown fashion accessory of the fish bowl. He plays a double part as himself and as his merciless control back home on Robo-World who is called Great Guidance. This is someone that no one would dare call GG. Despite the lobby poster shown above, neither of the Robot Monsters has a face. That must have made talking hard.

Great Guidance tires of hearing Ro-man going on about his existential crisis of conscience rather than the KPI. This crisis cuts in when Ro-Man seems to have started to rape Alice, by tearing her dress off, again crossing the prevailing code line. Fraternity brothers supposed that the sight of her wherewithal gave him a reaction.

Anyway, Great Guidance zaps Ro-Man from afar, and he dies. Such is corporate power when one misses the KPI targets.

The end! The end. The end? Not quite. Whereupon the annoying little boy wakes up and evidently it was all a dream. Maybe that it was all a dream, like life, excused the code violations, though it is hard to believe this title had much distribution to theatres.

George Nader is quite specimen here, seldom with his shirt on.

He played G-Man Jerry Cotton in more than a dozen West German films.

He played G-Man Jerry Cotton in more than a dozen West German films.

He left Hollywood and went on to a film career in West Germany. Like Eddy Constantine, Jess Hamm, and Lex Baxter he became the American in European movies. The word on the web is that Nader was a homosexual who found it increasingly difficult to get parts in Hollywood, at least parts that he liked, and Baxter was an old friend who suggested he try Europe. Some years later he returned Stateside to work in television.

‘Fire Maidens from/of Outer Space’ (1956)

It says it all when the distributors do not know the name of the movie. In England where it was made, it was released as ‘Fire Maidens from Outer Space’ while Stateside it went out as ‘Fire Maidens of Outer Space,’ giving members of the commentariat endless fun in a pointless discussion of the difference. Still it is not often that ‘Fowler’s Guide’ is brought into B-film reviews.

If that was not enough to signal the fun ahead, then there are the credits in which the name Cy Roth figures, repeatedly: A Cy Roth presentation, produced by Cy Roth, directed by Cy Roth, story by Cy Roth, screen play by Cy Roth, tea service by Cy Roth. See. For someone in love with the sight of his own name, Mr Roth is quite shy on the internet. I could find nothing but the scant entry on the IMDB. Not even a photograph. His other credits are few. Very. Conclusions to follow: Cy cannot present, produce, direct, write, stage, or pour.

The conceit of the movie is that the two great postwar powers, the United States and Great Britain combine to launch a manned space flight. Ah, the James Bond illusion that in 1956 Britain was a great power. As if. England was still rationing food and petrol. The war debt remained crushing. Victory had nearly destroyed England, just as victory had nearly destroyed France in 1918.

The early going is treacle. We see people walk down stairs, slowly, and then back up the same stairs, slowly. The action stops while the men light pipes. ‘Action?’ Well in fact, the only action is lighting the pipes.

Then with no further preliminaries than a voice over, the six spacemen strap into their office chairs (with rollers) for blast off. Stock footage of V-2 rockets and such follows. The wires are visible in some of the later effects. This must have been a quota quickie to supply British content, as legally required, for theatres. What other explanation could there be, Erich? Quota quickies are explained elsewhere on the his blog. To find out about them do the homework.

Their flight is interminable, or so it seemed. The goal? The thirteenth moon of Jupiter. Huh? Jupiter has dozens of moons and there is no saying which one is the thirteenth. The thirteenth in size, the thirteenth from Jupiter but that varies as some of the orbits are irregular, the thirteenth discovered, thirteenth from the left or from the right, the thirteenth in Republican voters. The scientists Roth consulted found that this moon is like Earth, so off they go. Vroom. In their V-2.

They pass flight time smoking. The number two never takes his naval hat off. That always makes me think the head in it is bald. Keep that hat in mind.

They land in Sussex, a long trip to end up there, and then go outside for more cigarettes. It’s all good. Someone throws rocks at them. (The audience?) They see an object and hear voices. They divide. One group stays with the rocket ship and calls home, repeatedly. Repeatedly. Those they call intermittently never move from their floor marks. It is one shot repeatedly shown to save costs.

The other three go to find the voice(s). On the way they cross three fields, repeatedly. By this time, the fraternity brothers were desperate for the Fire Maidens.

The three explorers show no interest in anything. Oh hum. Another day in space on a distant world for the first time! ‘Got a cigarette?’ They are as bored by it all as the audience, like one of those works of modern art that is intended to be boring. That is, until they find the Fire Maidens when they perk up a little. Not much.

They find a walled garden and enter it to find it is the Fire Maidens’ dormitory. What luck! There are scores of the women twirling around in short skirts no one wore on the street in 1955, except men in Scotland. The fraternity brothers came to attention.

They meet the top man, whom we shall style the Professor. Yes, it is a man. An old one. He tells the travellers that these are the last of the Atlanteans, as in ‘from’ or is that ‘of’ Atlantis. That explains why they speak English. (!) When the waters rose, the Atlanteans took to the skies, assuming the water would engulf all. That was a blunder, but once airborne they could not cash in their non-refundable Virgin Spaceways tickets so they went to the end of the line. Since then, as the millennia passed, the men have died out — why they died is never mentioned and the explorers, men themselves, have no interest in such incidental matters — but somehow new beautiful woman keep coming along. Maybe Prof is not as old as he looks?

When the conversation lags, which is often, Prof venerates a cheesecake picture on the wall, as his grandmother, as his daughter, as Aphrodite, as Hestia, as his mother, as whatever comes to mind. Not the sharpest laser in the block is the old Prof. Definitely emeritus material.

Here is the tricky part. Prof wants the travellers to stay, what with all these nubile girls around….and the need for more Atlanteans. The travellers don’t get it. Why does he want us to stay? It takes them a long time to get his drift. Whatever fraternity they were in must have been a sorry lot. Prof drugs them so they will not fly away and they sleep a lot. Great footage of the navy man sleeping with his hat on.

They sleep some more. (So did I.) Meanwhile one of maidens loves the leader of the spacemen. He may be a distant, cold, and arrogant fool but she loves him anyway.

He is one Anthony Dexter who once played Valentino and never got over it. His subsequent credits include some other Sy Fy entries, before he saw the light to became a high school teacher. Think about that. Valentino at the chalk board.

The three stay-behinds keep calling home. The team at home never moves between calls. The three in the dormitory sleep some more. Oh, and the Fire Maidens dance. Not once, not twice, not three times, but four. Music and choreography by Cy Roth? The men sleep; the maidens dance. Is this edgy or what? Or what.

The stay-at-homes finally come looking for the three wanderers because it is time to return the V-2 or they will lose the deposit on it. They encounter the rock-throwing creature of the feature who is impervious to their pistols, though since they fired from the hip, having seen too many westerns, it is doubtful they hit the barn door, so they subdue him with a gas grenade. It was a well equiped mission, cigarettes, pistols, and gas grenades. Check, check, check.

Meanwhile, the sleepers awake and make trouble. The Fire Maidens dance. The creature breaks in on a dance routine and the spacemen throw a gas grenade at him, while he is cutting in on the Fire Maidens dance, near an open flame amid them all.

Thanks to some quick typewriting by Cy Roth, only the creature is killed.

Oh, earlier Prof was walking in the garden and the creature killed him. That was an afterthought.

Freed of the tyranny of the old doddering Prof emeritus the Fire Maidens…yep, they dance. Six of them pair off with the visitors, but Valentino assures the others more Earthmen will come. When last seen the fraternity brothers were booking their tickets.

It is a well used trope in B movies, the island, mesa, cave, moon, valley, planet, swamp, town, castle, world, office building of women without men, who do not know what they are missing until the men arrive. Then they find out. Housework. Ironing. Babies. Shopping. Drunken husbands. Sweeping. Dusting. Putting out the rubbish. Moping the floor. Cleaning the toilet. It is an adolescent fantasy. Somewhere are women so desperate that they will want even…..spacemen.

Scifist, a blog on the history of science fiction films that is meticulous and amusing, does not deign to review this length of film, and it stoops to review quite a lot like it. The line had to be drawn somewhere and this title ended up on the far side. At 78 minutes it seemed longer and less than the IMDB score of 2.1 from 1,277 votes. To date it is the lowest scoring film I have watched to the end.

.