This book is a popular presentation of some serious studies in the psychology of perception and memory. It shows how counter-intuitive reality can be. It also overstates its case and enforces a technical vocabulary where it adds little or nothing to the general reader, who seems to be the target audience.

The video that made the authors famous and which explains the title can be found on You Tube. It is a psychology experiment in which observers are instructed to count the number passes a basketball team makes, and while the observers count, a gorilla walks across the court. Well, a student wearing a full-body gorilla suit, since the research grant did not run to capturing and training a complaint gorilla.

Imposible to miss!

Hmm, missed by about 50% of all subjects through repeated iterations and variations.

We can indeed miss things in front of our very eyes, and do so nearly every day. So I say from personal experience. Because we miss them, we suppose they were not there, but they were.

The explanations are many, and in these pages become increasingly, and needlessly, complex, no doubt to justify the grants that produced the fame and book contract(s). My cynicism is showing.

We see most readily what we are looking for. Indeed we often can only see something if we are looking for it, and in concentrating on that, we miss much else. Whoops! But then concentration is supposed to do that, focus.

In parallel we are less likely to see what we are not looking for, and the even less likely to see it, the more out of place it is. This latter is counter-intuitive. But that gorilla is an example. It is completely out of place and, consequently, invisible (to half the watchers). Another player, a coach, a referee, a cheerleader wandering onto the floor might have been spotted more often for the fit the context.

To reiterate. something extremely odd can be the most easily missed. See, counter-intuitive, because one would think the oddest things would stand out, but they do not always do so. Sometimes, yes, but often times no.

Add to this perception blur-memory and the plots thickens. If it is not perceived in the first place but is just a blur, memory cements over it, and it never happened.

The authors demonstrate these failings, which seem very plausible in my own personal experience, with a combination of laboratory experiments and case records of automobile accidents, flight simulator video evidence (nearly enough to put me off flying), conflicting eye witness testimony, and trial records. The range and variety of this empirical evidence is impressive.

One of the governing points is that our contextual expectations shape perception and also memory. We do not expect to see a gorilla while a basketball team practices passes.

There is also cognitive load, which the authors do not give any attention, but they do note that when the task assigned to observers is made more difficult, gorillas sightings decrease. For example, to ask observers to count separately air versus floor passes makes the gorilla all but invisible to everyone. The more complex the assignment, the more concentration it takes, the less attention remains to detect the unexpected.

There is another example of cognitive overload in these pages. Drivers who follow the GPS oral directions despite the obvious mistake it is making. They ignore flashing lights, barriers across the road, and drive off collapsed bridges, over the culverts of incomplete roads, and on to rail way tracks because the computer voice told them to do so. I would like to think I would not do this, but…. I have found GPS directions mistaken when roadworks blocked the recommended routes and had the wit to stop on those occasions. Who knows what the future will bring?

Of course, magicians and other illusionists have long exploited misdirection, distractions, sleights of hand, and lighting to make audiences see what the magician wants its members to see and not what is in fact happening before their very eyes. The authors have not yet referred to this domain in my incomplete progress through this book. Though the illusionists do not publish in ranked journals and apply for National Science Foundation grants, hide behind polysyllabic jargon, nor make mountains out of molehills as scholars must, so they may get short shrift in these pages.

There are many more ingenious experiments to justify research grants. If magicians are neglected so too is the simple fact of concentration. If I am concentrating on counting passes maybe I should not see the gorilla. Perhaps the observers who see the gorilla made mistakes about the pass count. Nothing is said about the accuracy of the observations, but if I were paying pass-counters that is what I would want them to do, count, not notice gorillas. Many of the examples given involve witnesses who are not concentrating. A student passes people on the street, and one says ‘Hello.’ Five minutes later the student cannot describe this person. Well, so what? If that student had been told the description would be on the final exam, it would have been remembered.

Two passengers in a moving car see an assailant pull a bike rider to the ground. Interviewed by police thirty minutes later and they give different description of the assailant. Again, so what? They were not concentrating on the scene. It was a blur.

Of course, the authors’ point, is in part, that such witnesses each individually think they do have an accurate description even when one, if not both, of them must be wrong. It is this confidence that is the underlying problem, and the authors nail that. It is the this also confidence that presents many problems. Agreed, but I am not sure this book has narrowed that down any.

Though in doing so, it seems like overkill. The messages seems to be that no one is ever right in the first place and subsequent memory further erodes. To give up would seem to be the best response to such a hopeless situation.

I thought of these two when reading about memory in this book.

I thought of these two when reading about memory in this book.

Hmm, well I just watched an American football game and there the players with enormous concentration remembering intricate plays from a manual of fifty or more, in a deafening stadium, driving rain, with hard hitting opponents, carrying injuries, and growing tired toward the end of the season and the end of the game. Memory does work better when one concentrates.

The authors offer some amusing anecdotes to illustrate the fragility of memory but to this reader that is all they are: anecdotes. Men often appropriate each other’s stories as their own in the retelling and when challenged about it, get very defensive. (I have even seen women do this.) What is going on in such cases is not primarily a false memory but a stupid lie followed by a masculine refusal to admit it. No National Science Foundation grant is required to explain this everyday event.

More disturbing are airline pilots in simulators who are so absorbed in reading gauges that they do not notice the tanker-truck on the runway.

A tendency in this book is to name a ….a what? … a syndrome, and then move on to another ingenious experiment. The missed gorilla and the missed tanker truck are treated as instances of the same tendency and yet they differ so much in context and consequence as to be different in kind.

Moreover, to this lay reader (I thought about say layman to see if it would arose a comment about gender but I forgot) that the nominalism is not very informative. By nominalism, I mean naming a pattern of (mis)perception – e.g, inattention to change, and suppose we now understand how it works. We do not; what we have, often in these pages, is a description with a label.

Charles Chabris

Charles Chabris

Daniel Simon

Daniel Simon

While I am airing my nits, I find the book replete with name dropping of colleagues and of universities. Perhaps some editor encouraged that to make it more personal and less austere and scientific for a general reader but it makes it read too much like a letter to mom identifying all of the fraternity brothers and sorority sisters. It is all of a piece with the me-ism of the selfie.

Warning! cynicism overload.

Author: Michael W Jackson

Dan Kavanagh, ‘Putting the Boot In’ (1985)

A krimi set in the world of British soccer. Our principal is Duffy, onetime fourth-string goal keeper and retired police officer. His retirement from the force was involuntary. Ahem. This is the second or third title in a long-running series.

There is quite a bit about the beautiful game, which passed over my head. I liked the ambiguous attitude and behaviour of the owner of the third division team at the centre of the mystery. If the team is relegated, well, he will sell the ground for a commercial development and, perhaps, break up the team. If the team has a few wins and hangs on, well, then he will stick with it long enough to sell it to another punter at a good price. Win-win for him. Not so for the fans whose team may disappear. Not so for the manger who will be blamed for relegation. Not so for most of the players whose fortunes are tied up with this team; there is not a lively market for fourth division players. A few of the better players will get other offers.

Some of the players are involved, along with the desperate coach for whom relegation of this team would be the end of his credibility and career in the Old Dart. He is so desperate he hires Duffy and pays him out of his own salary, which amuses both the owner and Duffy.

Duffy, per the back matter, is AC/Dc on sex. But here his battery is flat.

Someone has been nobbling the players. One has his leg broken in a choreographed mugging, while another is set up on a sexual assault charge. Duffy to the rescue. Well, sorta. In the end the leg will heal and the sex charge lapses when the complainant decamps, perhaps, because of Duffy’s pressure, or perhaps because the punter who paid her in the first place lost interest. Like life, it is unclear.

Duffy lives with Carol but that seems to be all. She has access to some police computers and that comes in handy when he can talk her into using that access for his purposes. Not often that.

Trouble is, I found the characters monotonous. They all blended. It seemed like a very long episode of ‘Minder.’ Neither much plot, tension, nor momentum, but some good one-liners.

Dan Kavanagh

Dan Kavanagh

I came across this title on the shelf in the Academic Bookstore across from Stockmann’s in Helsinki, and snapped the cover. Later I said hey presto and got it on the Kindle. I had no wish to carry the paperback around.

‘The truth is out there.’

Fox Mulder said that. Such a remark would have earned him a sneer in most universities, especially from philosophers, the more so for those who declaim themselves to be post-modernist.*

For the last two generations scholars and writers have been telling students there are no facts. Marxists denied the law of supply and demand as a fraud. Philosophers emerged from Plato’s cave. blinded by the sun, saw no facts but only heard words and more words. It was all relative. Then the post-modernists came along and bulldozed everything flat with Gallic subtlety. It is all subjective.

In a curious way even school teaching went along with this rarefied nonsense by increasingly ignoring facts. Students no longer learned facts, like historical eras, conjugations of verbs, the formulae for a solution, or the dates of queens and presidents. If such trivia was needed it could be looked up. This was the line long before Google came along.

As ever, the nonsense peddled in college and university classrooms seeps out with the graduates and in time it come back to haunt the groves of academe. What started as intellectual pyrotechnics, harmless fun, and oneupmanship, and the path to promotion is not so funny when it mutates and returns to bite. Think Godzilla.

Now politics in the United States, and to some extent in Australia, has practitioners who publicly and explicitly dismiss facts. The lesson has been learned. Climate change may be a fact but that does not privilege it. All is relative, a fraud, or subjective. Hearing a minister of the crown dismiss scientific evidence sounds like a philosophy seminar.

Social workers were bitten by their own arguments years ago when they espoused the conviction that disabled people should not be institutionalised as this further diminished them. In time the political class learned this lesson and closed the institutions to cut budgets, putting the disabled in ‘the care of the community,’ that was the phrase trumpeted by social workers forty years ago. That care is now to be seen in such people sleeping on the sidewalk and living in parks. In addition, the career paths created in larger institutions were closed off to social workers.

*I have always expect the worst when I hear the word ‘post-modernism’ and so far it has never let me down.

I hemmed and hawed about ‘oneupmanship’ but decided to us it since its prime exponents are men.

‘Arrival’ (2016)

We idled away a hot and humid Sunday afternoon at the Newtown Dendy to see ‘Arrival.’

First contact with aliens is a gold standard in science fiction. Many examples are shoot ‘em ups from ‘The War of the Worlds’ to ‘Independence Day’ and their kind. Nothing more will be said about these sort.

Before going to ‘Arrival’ I checked an on-line trailer to see if it met our preliminary standards, little or no CGI and little or no shoot ‘em up. CGI is Computer-Generated Images, which are a fatal virus in most movies these days, an easy substitute for thought. It passed these two tests which rule out most of the dross from the dream factory.

Off we went. What’s to like?

First and foremost its lead and star is a woman, who is neither glamorous nor trying to be a man. Amy Adams plays a skilled linguist named Dr Louise Banks. What she does is listen and think. That is a tough ask for Hollywood: thinking.

The usual currency for thought is the full face close up with wrinkled frontal lobes, but we get little of that here. Instead we get a lot of flashbacks, flash forwards, or flash sideways. I am not sure which, and will return to this point below. Adams does it well, and carries virtually every scene, certainly every scene worth watching.

The movie has pace but it is in no hurry. There is movement but not those crazy camera cuts loved by action directors who have never been in action themselves.

There is an intellectual puzzle — how to communicate with these aliens, who are very alien — placed in a high-pressure context.

We loved all those alien zeros with their minute differences.

They were incomprehensible. That is the mystery. What a relief from the NRA-approved Hollywood films, made by bleeding heart liberals, where all solutions lie in a gunsight. Bam! See any of the recent Star Trek movies. Incomprehensible is better than splat.

In the original ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ (1951 [and 2008]) Patricia Neal had to say ‘Gort, Klaatu barada nicto.’ It worked. Whew!

Gort.

Gort.

To do that she had to get to the right place passed the guards, overcome her own fears for herself and her child, and remember the incomprehensible message, and deliver it by rote to the scary robot. That was hard. Especially when his light went on. See above.

Dr Banks’s mission is infinitely harder. With all the same fears that Neal had, she has to figure our first what it means and then how to say it in zeroes. That is some tough exam. It is even more difficult than understanding something said by the Cheeto President-elect.

The biggest theme is time’s arrow which seems to be the governing narrative.

However, neither of the professional reviews I read from the ‘New York Times’ or ‘Sight & Sound’ mention it. All the flashes, back, front, side, seem to be about the simultaneity of time about which we might find out more in a sequel three thousand years later. (To get the point, see the movie.)

I also liked the understated Forest Whitaker for whom dealing with aliens is another day at the office. Indeed, he is almost catatonic. Of course, it is unlikely a mere colonel would have command of such a situation, though most generals would try to avoid the likely career-ending duty. The massive overkill of the U.S. response rings all too true. The motto of the Pentagon seems to be ‘Nuke the jaywalkers!’

Not so likeable were these things.

The dark cinematography defeated some of the exercise. I never did get a good look at Whitaker or anyone else. I expect it will be even more difficult on DVD.

See what I mean?

See what I mean?

The helicopter landing at the start is gratuitous, distracting, and unbelievable. The helicopter is seldom the fastest way to travel because its airspeed is nothing special, especially when in civilian airspace full of other aircraft. The noise distracts from the dialogue. It is unbelievable that a pilot would land in a wooded residential area at night.

‘They have to see me,’ Dr Banks says ripping off her Hazard Suit (coloured to remind us of ‘Space Odyssey’ I suppose) mask for no discernible reason than that its time to get that Hollywood star our of the glare of the plastic mask.

That the hero is bold where others hesitate is a tired trope trotted out here several times. Cemeteries are full of such bold wanna be heroes who never made it to celluloid fame.

The nicknames ‘Abbot and Costello’ come from nowhere and went right back there. While we silverbacks got it, did anyone else, or have these two execrable comedians been resuscitated? I hope not. Unless it referred to the two Australian politicians Tony and Peter.

The screenplay has its share of clichés. Top choice is the Chinese general who has mastered McKinsey-speak when he says that Dr Banks ‘reached out to him.’ I have heard that too many times from cliché-speakers who did the training course. At least he did not insert a meaningless ‘actually’ in his remark. The scene is good and the point is part of the mystery but all of that is deflated by this McKinseyism. The air went right out.

As expected, there is a hot headed soldier, though here the idiot is a working stiff who acts on his own with a few buddies, where in reality it would be an educated and overpaid general in D.C. who wants to blow something up to get another star. Think Sterling Hayden from’ Dr Strangelove’ (1964) and you have the reality of General Curtis LeMay, a one time vice-presidential contender. The aside with Russ Limbaugh, the most shocking of jocks, was perfect but added nothing here.

If the pointless tracking shots, and empty rooms were cut, we could lose thirty minutes and not notice it. It is too long and indeed the longer it goes, the less the tension. A slow leak is still a leak.

I have to enter a plea for the chain of command. In this movie a Chinese general acts without the authority of the Communist Party. Never. All those purges Mao unleashed were partly aimed at cowing the army and keeping under the thumb of the party where it still is. Nor would the Director of the CIA call the shots as rendered here. There is a president to do that. Gulp.

The director, by the way, is Canadian Denis Villeneuve who has many other credits that I have not seen.

Denis Villeneuve

Denis Villeneuve

Seeing this reminded us of the other First Contact movies. Chief among them is ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ as mentioned above in which a passive alien ambassador is murdered by a trigger happy grunt to the cheers of Russ Limbaugh and his kind. Then there was Jodie Foster in ‘Contact (1997).’ A cut above the mill, this one is for its intelligent screen play. In a class by itself is ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977).’ As is ‘Paul (2011),’ though this not really first contact it is unexpected contact. There are also many instances in the Star Trek canon before the franchise descended into CGI shoot ‘em ups. Some of these are very thoughtful when thinking was still valued out west.

‘Aunty Lee’s Delights’ (2013) by Ovidia Yu

A light weight krimi set in Singapore. ‘Light weight’ is the kind of krimi I like. Not too serious, not too violent, not too graphic, and not too demanding on the little grey cells. I will admit of exceptions like Ross Macdonald and Georges Simenon, but they are few.

This is the first in a series focused on Aunty Lee’s home cooking restaurant in the island city-state of Singapore. Madame Lee is a woman of substance but she loves cooking and running her small restaurant for a crew of regulars since it is far off the beaten tracks in Singapore. She also has a long established and island-wide network of cronies and contacts, some of them from her late husband’s business empire. The final ingredient is her nose for news, i.e., gossip.

The fire is lit when the plastic wrapped dead body of a young woman washes up on one of Sentosa’s beaches. ‘Sentosa’ means peace and tranquility and tidal corpses do not fit the tourist board image. Sentosa also generates enormous income from the twenty million visitors a year who go to this Asian values Disney-like land.

Aunty Lee gets along well with her stepson Mark, who is unable to emulate his father’s business success, but not with his insufferable wife, Selina. She was so insufferable in the early pages I thought, applying years of viewing episodes of ‘Midsomer Murders,’ that she would be the first victim. Alas, no. Though she does largely pass out of the story, or my reflexes have improved and I managed to flip the pages upon which she appeared so quickly I did not notice. I did enjoy a smile when she reappeared toward the end, and the villain slipped her knockout drop so that we readers did have to endure more of her endless verbal and sub-verbal tirades. What’s her problem? She is rich, but not rich enough. And never will be.

Madame Lee’s crime-busting irregulars include Nina, her Filipino maid, and Sergeant Salim, a Malay Muslim, in a city of Chinese Christians and a few others as she pursues the Sentosa murderer. When the victim is identified it is someone she knew. Then there is a second…. Also known to Aunty Lee. This is too much! It’s personal!

I learned quite a bit about the legal status of guest worker maids in Singapore. Sergeant Salim’s outsider status has advantages and disadvantages, as he well knows, and he is learning to capitalise on the former, and gets a few tips from Aunty Lee about managing the latter. That maid, Nina, has her own network to bring to the table.

There is some to’ing and fro’ing in the miasma that is Singapore. A major plot concerns gay couples, and coupling, in Singapore, where it is ILLEGAL! That seemed an odd foundation for the series, though it is well handled, and by the smoke and mirrors of authorship Sergeant Salim is never directly confronted with this crime.

The villain was not hard to spot for us hardened krimi readers but how he came into contact with the two women and dispatched them was neither convincing nor interesting. It also seems to me that early on we had far too much of the egregious Selina for no other purpose than the relief at her subsequent absence. She played no part in the plot. Yes, I now about the false text message but the egregious Selina was not essential to that.

Ovidia Yu

Ovidia Yu

These quibbles aside, I shall certainly read the second in the series.

In my many business trips to Singapore I never made it to Sentosa. I did walk through the Raffles lobby once and shopped for underwear at the Marks and Spencer, and have since stuck to the M&S house brand via email order. I rode around on the red bus once. Loved the Aladdin’s Cave of the Mustafa Centre, especially before it got all cleaned up. Battle Box in Channing Hill was a grim reminder of the War, as was the replica Changi Chapel. [Moment of silence.]

I had a memorable Thai meal in Singapore in which I made a fool of myself. Long story. Short version: having traveled in Thailand I thought I knew Thai food. Wrong. On all my visits in Thailand the hosts always knew I was coming and all the places I stayed catered, I later realised, for the western palate. The meals in university restaurants and hotels are not the real thing. But place we went in Singapore was! I was hors de combat quick smart.

‘Franklin Pierce’ (2010) by Michael Holt

Franklin Pierce (1804-1869) was the fourteenth president of the United States, 1853-1856.

His father had been a New Hampshire militiaman in the Revolutionary War, and his two older brothers had carried muskets in the War of 1812 against Great Britain. Pierce grew up in a family that was among the founders of the new nation, and self-conscious of it.

His war leadership put his father into the governor’s chair in Concord, and the boy Franklin accompanied him on his rounds of meeting voters throughout the Granite State. He was suckled on politics.

He was an indifferent student, preferring the recreation of an outdoorsman, killing: hunting and fishing. He was clean cut and of pleasant appearance. Not so handsome to make men jealous but nonetheless attractive to women. He also had learned, observing his father, how to get along with people with whom one had little in common.

The political parties at the time were decaying and re-newing. In the first generation of the republic the two alignments had been the Federalists, who favoured a strong central government for defence, supported by taxation versus the Anti-Federalist, who favoured ‘that government which governs least.’ Among the Federalist was Alexander Hamilton and among the Anti-Federalist was Thomas Jefferson.

The cleavage between these two blocs was partly regional with New England and the mid-Atlantic states generally favouring the Federalists, while the tidewater and southern states were the home of the Anti-Federalists.

Because they lived by trade, the Federalists states wanted the central government to impose tariffs on imports, build harbours and roads, and guarantee banks to further their business interests.

The Anti-Federalist feared these powers would disadvantage their plantation economy based on slavery. They were also mindful that the Constitution’s provisions for slavery were tenuous, and feared a strong central government, dominated by Northerners, would undo some of the Constitutional measures sheltering slavery.

Collision occurred when local improvements, like docks and ports, were bruited and when a Bank of the United States was chartered to regulate and guarantee private banks.

To Anti-Federalist each of these initiatives was unwelcome because each enlarged the federal government. Moreover, taxes on their goods would pay for piers in Boston Harbour and roads in New York state. Meanwhile, the goods the south imported would suffer a heavy tariff. So went the argument in the South.

It was masked as states’ rights. That old sour song still heard today. The champion of this repertoire in Pierce’s time was Andrew Jackson and the Democratic party he created. Though when Old Hickory became president he did not hesitate to use the powers of the Federal government against the states. Go figure.

Meanwhile, with the passing of the Adams dynasty, the Federalists evolved into the Whig Party which advocated the rule of law, a written and unchanging constitution, and protections for minority interests against majority tyranny. It was business friendly. Four presidents served that party, William Harrison, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and Millard Fillmore.

Generalisations aside, Pierce became a Democrat, swimming against the tide in Federalist and Whig New Hampshire. In this study there is no explanation for this initial affiliation. Car license plates bear the state motto: ‘Live free or die.’

These words graced the New Hampshire colonial flag in the Revolutionary War. It has been the only state where seat belts are not mandatory, and cigarette advertising is not constrained.

Pierce actively opposed local improvements in the Granite State, the state nickname, to stay the dreaded hand of big government, and that led him to a seat in the state legislature where he proved an effective organiser of interests and votes, and companionable fellow. After five years or so he ran for Congress, and the same state legislature elected him and off he went to Washington to curb the dragon in its lair.

His young wife stayed in New Hampshire for her health was and remained fragile. In D.C. he got along with Whigs personally but was a staunch Democrat.

The next step was the Senate and the New Hampshire legislature voted him into one of the state’s seats, and back he went to Washington. However, he stayed only a few months and resigned.

Why?

Multiple causation, perhaps. First, his wife, Jane, refused to go to the swamp of D.C. Second, Pierce had taken the temperance pledge with his father and brothers, and he found it difficult to stay dry in D.C. where he shared a house with four other congressmen who did drink alcohol. To escape the clutches of demon rum, he returned to Concord.

It also seems to this reader that Pierce, after the novelty wore off in D.C., found himself a small fish in a big pond and he did not like that. Back in New Hampshire his was a name with which to be reckoned and so he went back there.

His wife briefly thought he would quit politics and into legal practice, but no. He became chair of the New Hampshire Democratic Party and he ruled that very effectively. He recruited leading lights of towns and villages across the state as members, travelled the state to seek them out, and placed an absolute premium on party unity. No dissent was tolerated. Office holders soon found that an unguarded comment contrary to party policy would see them recalled, unendorsed, banned, and otherwise disciplined. No exceptions. No warnings. No second chances. He was one-man nomeclatura.

Then came the Mexican War. Pierce had no military experience or interest but he knew that he could not sit it out, though he did not rush to volunteer: to be a simple soldier would not be enough for his ego, it seems. After a few months the Granite State governor, acting on a request from Washington D.C. to raise troops, commissioned Pierce a colonel to raise a regiment. He did, and proved himself again an expert organiser.

By the time his ship got to Vera Cruz the war had moved inland and it fell to him to organise the supply line. He did that very well.

However, the three times his command came under hostile fire, he was nowhere to be found… The author gives him the benefit of the doubt (illness, injury, and indisposition) but the men in his command did not. He was widely criticised by the mumblers in the ranks who were all New Hampshire men. But somehow he lived that down by assiduous application to the logistics duty that had fallen to him.

While in Mexico he met many others from across the country whose paths he would cross again later. That service was like a seminar for a future generation of national political and military leaders.

The Whig Party was dividing over the single issue of the day — slavery, masked behind rhetoric of states rights. It had northern and southern wings and within each there were further divisions over the details of the package of measures known collectively as the Compromise of 1850.

The prospects for Democrats were good. In New Hampshire Pierce’s name was bruited as a presidential candidate, but there were others with better, national profiles. Pierce followed the advice of an associate and postured. He had, he said in a published letter, no interest in a higher office that would take him out of New Hampshire….unless he was called to it. It was an obvious signal that he was waiting for the call.

His tactic was to wait and see if the front runners — Lewis Cass, James Buchanan, William Marcy, and Stephen Douglas — would defeat each other and in so doing, exhaust the nominating convention. They did, refusing to compromise among themselves.

After more than forty ballots in Baltimore, Pierce’s name was put forth, and a few ballots later he won the nomination. He became the Democratic candidates in the election of 1852. He was fifth choice.

As was the custom of the day, he did not campaign but remained at home. His supporters did the grunt mostly through the myriad of small town newspapers.

Meanwhile, the Whigs continued their immolation with contending candidates and opposing declarations of intransigence. The incumbent president, Millard Fillmore, a Whig, was denied re-nomination in favour of the Mexican War hero Winfield Scott who was vehemently opposed by southern Whigs as unreliable on slavery. Instead they advocated abstention. Fillmore flirted with the Free Soil Party which favoured opposed the spread of slavery into new states. Scott did nothing …. to court Southern voters. Scott did very little. He had a well deserved reputation for sloth and he lived up to it.

Strangely enough there was a third party candidate, one from New Hampshire, who ran as a Free Soil candidate. Remember those mumblers in the ranks? He got their votes.

Pierce won by a landslide and that was the beginning of the end for the Whig Party, but it left him with a very large party that was anything but united. His Electoral College vote was five times that of Scott, whose political career ended then and there. Congress, too, was replete with Democrats. One of the states where the vote was closest was…New Hampshire.

Super-majorities are invariably undisciplined, and this was never more true that with the huge Democratic majority that assembled in Washington, D.C.

Pierce stuck rigidity to his conception of unity by adherence to the strict letter of the law, even when those letters, having emerged from compromises in Congress, were deliberately vague. In each and every matter, Pierce, after some confused posturing in convoluted messages to Congress, would side with the interpretation of the murky laws taken by the slave-states, perhaps because of his Jeffersonian DNA which rejected any role for the Federal government in nearly anything.

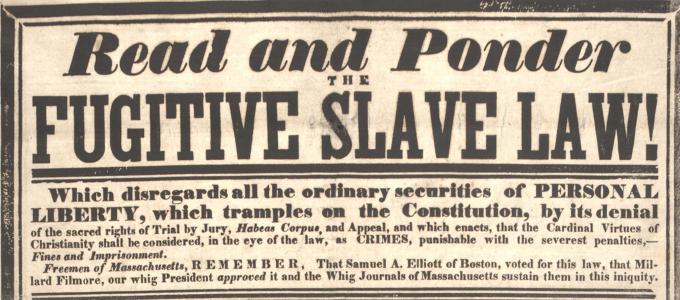

The Compromise of 1850, a set of measures that admitted California to the Union, thereby upsetting the exact balance of the Senate between slave and free states, imposed the Fugitive Slave Act, and proposed local sovereignty on the question of slavery in two future states in Utah and New Mexico (very far in the future). The Fugitive Slave Act made it a Federal crime for any citizen not actively to apprehend a fugitive slave with the presumption that all blacks were slaves. It kindled significant and protests in Maine, Massachusetts, Illinois and elsewhere. In effect northerners were charged to impose slavery.

Then there was Nebraska! At this time the term Nebraska referred to everything west of the Missouri River marking the boundary with Iowa to the Canadian border, and west to Oregon territory. It included everything north of the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. Today that would be Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Kansas.

Land hungry immigrants, perhaps three million of them, were pushing west and railroads wanted to bridge the continent to the legendary riches of California. But the vast tract of Nebraska was lawless and government-less as well as roadless. To sell land to migrants, to license railroads the land had to be surveyed and governed. Hence the pressure to create territories, as the first step to states.

The Unorganised Territory was called Nebraska.

The Unorganised Territory was called Nebraska.

The prospect of more new states threatened further to erode the Southern block in the Senate, and slave interest mobilized. First to stop any development in Nebraska, but that failed because the pressure was too great from migrants at the bottom and railway magnates at the top of the demand curve. The second line of defence of the slave states was to revert to the Missouri Compromise formula of 1820 and admit states two-at-a-time, one slave, one free. This proposal galvanised a reaction from the abolitionists in New England, small in number but mighty in pen. Pierce had a visceral reaction to these agitators.

The result was the Nebraska War in which settlers poured into the area to vote in a plebiscite on slavery. Abolitionist arrived from the north and thousands of Missouri slave holders crossed the river long enough to vote and then leave. Since the easiest access was through St Louis, contending parties often encountered each other along the way and the first skirmishes of the Nebraska War occurred in St Louis.

The South won this war by stacking the electoral rolls with far more voters than did the abolitionists, thanks to the proximity of Missouri, and they voted into office in Kansas, a pro-slavery territory government situated in Lawrence which applied for statehood as a slave state. In many locales the votes for the slavery outnumbered the voters by a multiple of five. The electoral fraud was extensive and blatant enough to make a Florida Republican proud.

The abolitionists, called Free Soil, who wanted to keep all blacks out of Kansas, free or slave (unless they could play football), challenged the legitimacy of this territory government and set up their own rival Free Soil government in Topeka. What a devil’s brew this was! Does this explain why the Interstate Highway to Topeka today has a toll, unlike every other Interstate? (Yes, I have read the official explanation and I know there is a similar instance in Pennsylvania.)

Pierce sided immediately and unequivocally with what he said was the legitimate government in Lawrence and prepared to send in the army to support it. Of course that was the very point at issue, was it the legitimate government? Even some of Pierce’s own cabinet thought it was not, and suggested alternatives, like another closely supervised election.

Pierce viewed that as equivocating, and I suspect also from the tone of his recorded remarks he also took that suggestion as a slight on his person, and rather than admit a mistake, he redoubled his efforts to bolster the Lawrence government. The result was the Jayhawk War between the factions in Kansas which caught in the middle many of those land hungry migrants. In this war the United States Army took the part of the slave-favoring government in Lawrence. This step inked the printing presses of the abolitionists for whom Pierce was the slave master in chief.

Three years into his administration, Pierce was hailed in the south as a true friend of the Constitution, i.e., the slavery enshrined in it, and widely reviled in the north, foremost by the abolitionists, but also by northern mercantile interests who found that in many other smaller ways he favoured the agricultural interests of South over their interests. Western migrants also disliked the use of the army to impose policy. That was too much like back home in Europe.

While Pierce’s public statements were full of patriotic fervour about his love of the United States, specifics were absent. Like so many since and now, he seemed to have disliked most of the reality while declaiming his love for the abstract, ever ready to embrace the flag on the stage, but not a person in the street. It is ever thus.

Further, the Democratic Party was suffering some earthquakes within its ranks, as the subsurface plates of North versus South and East versus West shifted. Ambitious rivals like Stephen Douglas and James Buchanan paraded their wares. While Douglas has been deeply involved in the politicking that led to the impass, Buchanan had been United States ambassador to London and was free of baggage. Douglas was energetic and brash, while Buchanan was discrete and subtle.

Pierce wanted renomination, but soon realised it was impossible. Like Fillmore and Tyler before him, he was cast aside by his party. The nominee was Buchanan, who then won the Presidential election, thanks to the continuing mutually assured destruction of the Whigs.

Pierce repaired to New Hampshire to sulk after the inauguration of his successor, which he handled with some dignity.

Events rolled on, and when the Civil War came he could not resist some ‘I told you so’ public remarks that aroused the censors. To their inquiries he reacted in high dungeon. None of this was a productive turn of events. He made it worse by his belligerence, and, indeed, his remarks, as quoted in these pages sympathise with the South as the wronged party. Additionally, the timing was as bad as possible, because he made these remarks on 4 July 1863 even as news of the great Union victory at Gettysburg was on the telegraph wires. Some suspected he was a Copperhead or at least a Doughface. The former is an active Confederate agent and the latter a trustworthy sympathiser.

His wife continued to live with her sister, suffering from and finally succumbing to tuberculous. The last of the children died in a train derailment when the Mr and Mrs Pierce were travelling to Washington for his inauguration. It was terrible shock to both of them and she never got over it. He seems to have sublimated it.

He turned himself into a farmer and spent some of his time with Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose high opinion of Pierce is the one thing that give me pause, for Hawthorne was an insightful man. How else could he have written ‘The Scarlet Letter’ with a nose for hypocrisy as per ‘The Blithedale Romance.’

Pierce turned ever more to drink and died of liver disease in a few years. Visitors to his farm had often found him in a stupor.

Like so many other presidents, Pierce had no contact with his VIce-President, William King, who was a supporter of Buchanan. In fact, King was sworn in as Vice-President by the American counsel in Havana, where King had gone to seek relief from tuberculous. He died a month after taking the oath. He was a Vice President who never foot in Washington D.C. That left the President Pro Tem of the Senate as next in line for three years and ten months.

The book reads like a synthesis of existing knowledge and not original research. There are no quotations from any personal letters by Pierce. I guess that is inevitable in a series where the emphasis is on complete coverage and not originality.

So what?

Michael Holt

Michael Holt

The result is quite a distance from the subject because the author has no evident first hand contact with the subject, i.e., he has not held the letters or papers Pierce wrote, nor visited the sites in New Hampshire, nor looked at the local newspapers, but instead harvests from other studies who authors have done that. It is called desk research.

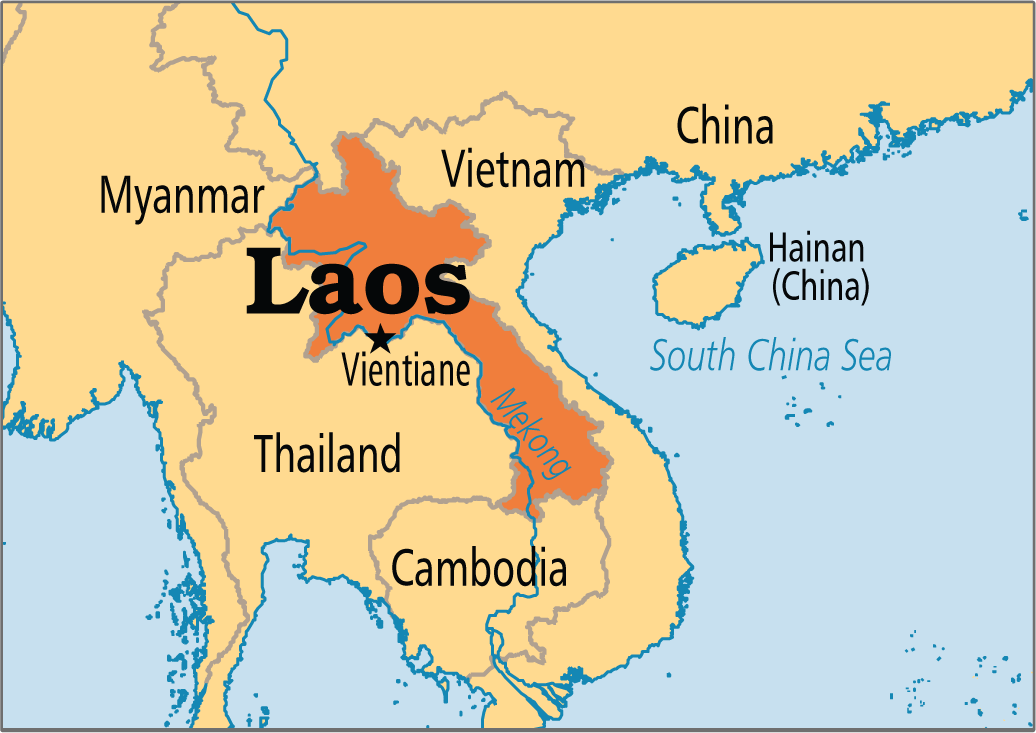

‘I Shot the Buddha’ (2016) by Colin Cotterill

Siri Paiboun is a retired medical doctor in the Laos of 1970s when it had plunged deep in the red water of communism. During the long struggle to reach that water, Dr Siri was with the patriots in the red alliance, saving many lives in battles with the French, the Americans, the Thais, and the Vietnamese. Many survivors of those wars are grateful to him.

In the red dawn, elderly and banged up from his years of hardship in the jungles, Siri became the national coroner. There are many bodies buried throughout Laos and Dr Siri unearths more than one, not all of whom were killed in the line of duty much to the chagrin of great and (not so) good of Vientiane.

This latter career is the spine of this series, now in its eighth title.

The time machine of these pages offers a travelogue to Laos of the 1970s, an impoverished, depopulated, ideologically-driven polity surviving with broken-down Soviet equipment, dealing with American sexual diseases, living off smuggling across the river to Thailand, and coping with the ancient spirits of the land.

The books have the form of a murder mystery which is salted with more and more elements of fantasy as the series has continued.

Dr Siri is a medium for the spirits of Laotian myth and the undead of those killed in the many wars of the land. Not only does he see ghosts now and again, he also negotiates with them.

Ghosts are not part of the Five-Year Plan, the Comrade Doctor is repeatedly told. But what choice does he have, when the ghosts appear. He has to answer before the spirits makes things worse.

There are many caustic comments on the corruption and stupidity of the stultified regime, consisting many of the dregs of the society jumped up to the top without either ability or experience but a manual of communist clichés that fit no occasions. This is no accident because the fraternal very big brother, Vietnam, prefers a crippled and compliant regime on its border.

During the course of the previous novels, Siri has gathered around him a group of associates. First and foremost is Madam Daeng, an entrepreneur of noodles, Phosy a frustrated police officer, nurse Dtui whose talents exceed the imagination of her formal superiors, and Mr. Geung, the Mongoloid janitor who simplicity cuts through subtrefuge more than once.

That is the inner party. They are also joined from time to time by others like the mad Indian, Ravi, who stands in the river for days at a time, and others who idle around the noodle bar in the hope of alms. Since Siri married Daeng and moved in with her, he has turned his house into a homeless shelter with all manner of residents.

One resident was a Buddhist monk who then disappears after leaving Siri a cyptic message about a new Buddha. Why did he leave and where did he go? To find out, read the book.

Colin Cotterill

Colin Cotterill

The early titles in this series had zest and clever plots along with all those colourful characters and travelogue. The eighth entry at hand has neither zest nor wit. The energy level is so-so and the plot … what plot? Whenever a plot thread dissipates, a ghostly spirit steps in and re-sets. Each such episode serves only to allow the author to take some very cheap, Bill Bryson-like shots at any one and every one, from Thai army officers, to monastery abbots, bus drivers, Laotian officials, rice farmers… This adolescent humour at the expense of defenceless others does not long sustain this reader’s interest. It reads like it was grind to write; it is to read.

‘Inspector Singh investigates a Frightfully British Execution’ (2016) by Shamini Flint

The overweight, crotchety, curry gobbling, beer swilling, stained necktie wearing, disheveled, immaculate tennis shoe wearing Sikh inspector of police is on the job again. Hooray! This is the seventh title in the series.

Singh is a Singaporean, though many there deny it, most of all his superiors in the police force, who repeatedly send him on foreign assignments, like the one in this story, to get him our of mind and sight. He is indeed an ambulatory eyesore, a fact that he is quite comfortable with.

Singh goes to London on an exchange program where he is assigned to review community policing! Those who know Singh, know what he thinks of that. Sitting at a desk reviewing case files is not what he does.

The sojourn is made all the more difficult because Mrs. Singh, she of the curries, has come along, too, over his prostrate body for he tripped over her suitcases. Her unnumbered family has many colonies in London which she plans to visit bearing gifts.

While he finds plenty of good curry in London, and that is crucial, he also finds….. While the formal assignment is a report no one will read, he soon becomes aware of a hidden agenda. Someone wants an investigation of one cold case, and preferably done by someone who is not as rule-bound as the Bobbies have to be for fear of offending anyone in a community. For that kind of job Singh is just the man!

In between enormous curry meals that leave him nearly comatose, Singh barges around asking the questions the ever so polite Bobbies dare not ask, least they give offence to some member of the community. It is quickly apparent that many lies have been told and that further piques his interest.

Shamini Flint

Shamini Flint

The mix of the serious and the comic in these krimis is disconcerting to this reader. Much of this krimi is pretty grim. Not to my taste. But much is jocular and light.

The 100 Greatest novels?

We spent several hours, day and night, discussing Robert McCrum’s list of ‘The 100 best novels written in English’ from the ‘Guardian.’

Google will produce several associated lists but the one I mean is found at

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/aug/17/the-100-best-novels-written-in-english-the-full-list

The list is the product of two years of ‘careful consideration.’ The introduction refers to the list as the ‘greatest’ novels.

The work must be a novel and written in English. When we went through the list we also supposed there was an additional element, every author only has one novel listed. They are listed in chronological order.

Yes, one can quibble over the definition of a novel, or even perhaps written in English (see the impenetrables below); entertaining perhaps, but hardly productive. And then there is that word ‘great’ constrained by the number one hundred. What does make a novel great? On there a few words at the end.

We read the list and discussed what we knew about each writer, or took note of writers that were unknown to us, consulting Professor Wikipedia at times for more information.

The list begins with ‘The Pilgrim’s Progress’ (1678) – a ‘story of a man in search of truth told with clarity and beauty,’ says McCrum. Much as we like Geoffrey Chaucer’s ‘The Canterbury Tales’ (1386), a novel they are not.

Robinson Crusoe, Lemuel Gulliver, Tristram Shandy, Tom Jones, Clarissa, Emma, and Dr Frankenstein get their dues.

The first krimi is Wilkie Collins’s ‘The Moonstone’ (1868). Though Edgar Allan Poe is there with his one spooky novel, along with Arthur Conan Doyle, Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler follow, but not the uncrowned king of noir, Ross Macdonald. Tsk. Tsk.

We loved the description of George Elliot’s ‘Middlemarch’ (1872) as ‘a cathedral of words.’

Benjamin Disraeli is there, before he became British prime minister, but also Jerome K. Jerome. Who?

There were others that struck no bell with me:

George Gissing, ‘New Grub Street’ (1891)

Fredrick Rolfe,’ Hadrian the Seventh’ (1904)

Max Beerbohm, ‘Zuleika Dobson’ (1911)

Sylvia Warner, ‘Lolly Willowes’ (1926)

Henry Green, ‘Party Going’ (1939)

Elizabeth Bowen, ‘The Heat of the Day’ (1948)

Elizabeth Taylor, ‘Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont’ (1971)

Marilynne Robinson, ‘Housekeeping’ (1981)

Penelope Fitzgerald, ‘The Beginning of Spring’ (1988)

Joseph Conrad’s ‘The Heart of Darkness’ (1899) made the cut. But is it a novel or a long short story? Quibble. Quibble. The trouble with quibbles.

Also on the list is the impenetrable prose of Theodore Dreiser of whom is it is said ‘he was no stylist.’ Indeed. Speaking of the impenetrable, there is Ford Maddox Ford, ‘The Good Soldier’ (1915) and James Joyce, ‘Ulysses’ (1922).

While there were many famous titles, I was not sure all were great novels. There was John Buchan’s ‘The Thirty-Nine Steps’ (1915) which is a rattling good story, but is it a great novel? It may be the cornerstone of the espionage genre that followed, but is that enough to merit inclusion when Agatha Christie is omitted?

It will take a lot more than assertion to convince me that Ernest Hemingway wrote a great novel. The title is ‘The Sun Also Rises’ (1926). Oh hum. I also wondered about John Dos Pasos, ‘Nineteen-Nineteen’ (1932) and ‘At Swim-Two-Birds’ (1939) by Flan O’Connor and — most of all — H. G. Wells with ‘The History of Mr Polly’ (1910). For Wells I might have swallowed one of science fiction titles like ‘The Time Machine,’ ‘The Invisible Man,’ or ‘The War of the Worlds’ but not this trite and self-indulgent disguised autobiography.

While the demigod William Faulkner is there, the novel cited is not his most astounding. ‘As I Lay Dying’ is the one, but his most hypnotic novel is ‘Absalom! Absalom!’ (1936). The novel he thought was his best was ‘The Sound and the Fury’ (1929). By ‘best’ Faulkner meant the most painfully true.

One book authors are here like Harper Lee.

Carson McCullers who is in another, higher league than Harper Lee is not, nor is William Styron.

Two towering English writers are also conspicuous by their absence: Barbara Pym, ‘Excellent Women’ (1952) and Antony Powell, ‘A Dance to the Music of Time’ (1951-1975). Also absent is John Galsworthy, ‘The Forsyth Saga.’

The list ends with a number of contemporary writers, most of whom leave me cold, e,g., Martin Amis, John McGarhan, Don DeLillo, and Peter Carey. More oh hum from me.

In addition to the expatriate Peter Carey, Australia is represented on the list by the egregious Patrick White. Absent is the luminous David Malouf; when will the Nobel Committee wise up?

David Malouf

David Malouf

There is a Canadian writer, or two, but not the profound Gabrielle Roy, a bank clerk by day and a communicate with eternity by night. To this day she is listed on the Amazon Canada web site as Roy Gabrielle, despite many corrections offered by we readers!

Whoops, Roy did not write in English.

Nor does Willa Cather make the list, and the list is poorer for it.

Robert McCrum

Robert McCrum

Coda

The pleasure of an exercise like this is that it makes one stop and think, first about the old friends on the list, also about the titles and authors one knows of but has not read. It also introduces new authors and other titles for the reader. Each is welcome.

But most of all it makes one think about the criterion: great.

Is a great novel one that influences other writers?

One that wins readers across generations and cultures?

Is it one that creates an enduring world with its words?

Is it one that leaves an indelible impression of the mind of a reader?

A great novel is one that does such things because there are many, even several, ways to be great.

‘Conclave’ by Robert Harris (2016)

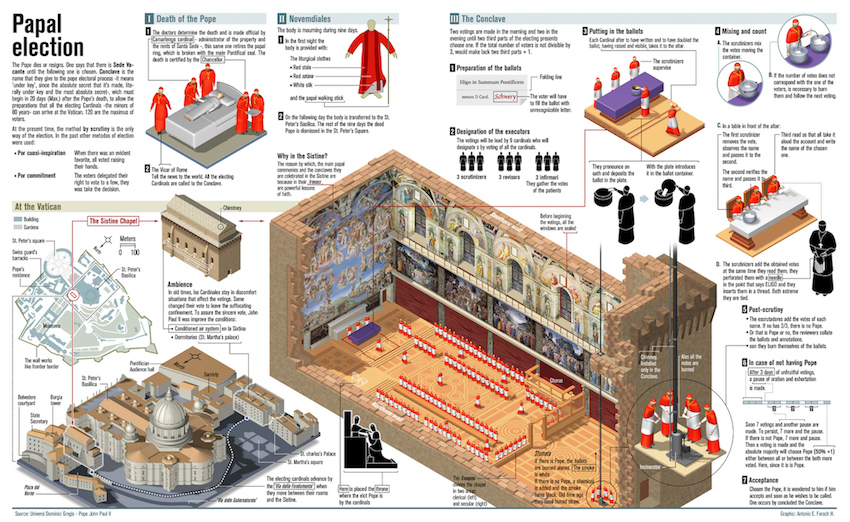

What is the oldest continuing electoral system in the world? It might be the conclave that elects the Bishop of Rome, known to the world as the Pope. For a thousand years a closed meeting of eligible voters has chosen the next Pope.

When the conclave has started the last few times, I have wondered how it works behind those closed doors. When I have brought up this question – how does it work – with colleagues and friends none have taken any interest in the subject, neither the psephologist nor the theologians of my acquaintance. I left it at that on those occasions.

When I saw this title, I picked it up in the hope it would shed some light on some of the mysteries. It does!

Behind the closed doors there is a very specific procedure which has ancient and holy origins. Pedigreed it is, but it was only codified and published in 1996 by Pope John Paul II in the Apostolic Constitution. (See Wikipedia.) An earlier initiative in 1970 limited voting to cardinals under the age of 71.

In sum, there is a manager of the process from the Curia who looks after all the details of travel, housing, security, and so on, and chairs the voting sessions. There are two sessions each day. There are no preliminaries beyond the social niceties as the cardinals gather in Vatican City on the day before the Conclave begins. The next day they convene behind locked doors and vote. There is no talking, just praying, meditating, and voting.

The ballot is secret and they vote by writing the last name of the cardinal they support on a piece of paper and drop it in a receptacle. They do this one-at-a-time so the process is slow. A printed list of call cardinals is on each desk. They do not talk in the Conclave.

The votes are counted by three cardinals, previously designated by the manager, who in this case blindly drew names from a box. Selection is done publicly before the assembled cardinals. To count, each ballot is extracted one at a time, and the name on it read aloud. For 118 votes all of this takes time.

But wait there is more! When this count is done a second group of another three cardinals, also chosen earlier at random, recounts the votes, this time silently. When it confirms the results, the manager announces the distribution of the votes.

This practice stems from the mistrust and brutality of Papal election in bygone days. Think of that Borgia pope whom Jeremy Irons played as a clown.

To gain the crown a candidate must have a super-majority of two-thirds of the total vote. If no one reaches that figure, there is a break for lunch and another session in the afternoon. The proceedings are punctuated by pauses for prayer and meditation before and after each vote.

If someone secures the two-thirds majority, the deed is done. However, if after eight votes, no one reaches the super-majority, then in the ninth and any subsequent ballots the bar is lowered to a majority of fifty percent plus one of the votes cast.

As in any election, the greater the majority, the greater the moral authority of the electee.

The book is replete with such details and I found all of that very interesting. I will return to these formalities later, but there are also informalities to consider.

No one declares candidacy, but there are candidates aplenty in this story. There are many Italian cardinals and there are recognised leaders among them, more than one.

Leadership can take several forms, as an advocate of certain theological position, as an office bearer in the Curia, as an organiser of good works, as ….. Of the two leading Italians in this story one is an advocate of a return to old time religion of the Latin mass, the denunciation of Islam, etc and the other an intellectual who has long been Secretary of State for the Vatican City and is known far and wide as thoughtful, rational, cooperative, constructive, and one who can get things done.

In addition, the third world cardinals coalesce from the first dinner around an outstanding exemplar, though it not so clear to this reader why they he is so esteemed, apart from his titanium self-confidence.

The Curia always has an implicit candidate and in this account he is a Canadian, who, as the story unfolds, has been for years distributing Papal monies in a strategic way. (Guess!)

At the first dinner on the arrival date, these leaders sit at distant tables surrounded by their supporters. Any high school class president would recognise the pattern.

None is without sin, and each falls along the path of the voting. There is much drama, and the outside world intrudes.

The details about the voting left a few questions for me. Cardinals over seventy attended in this story but evidently they did not vote. What then did they do? Nap through the Conclave? They came all the way to Rome to nap, well, to show solidarity, but still it seems strange to command that they travel to Rome and yet once there to regard them as too infirm to vote with intelligence and good faith.

Moreover, it was not clear to me if the two-thirds requirement was based on eligible voters (those seventy and under) or all in attendance, one hundred and eighteen in this story, or the vote cast, though no one seems to have abstained in this story. Maybe I missed the explanation.

I was also surprised to learn that cardinals have different titles, Cardinal-Bishop, Cardinal-Priest, etc.

My reading left some gaps in the plot. I never did figure out who identified and sent for the Nigerian woman who was the downfall of one candidate. Nor was I sure why his one sin thirty years ago disqualified him.

Spoiler alert!

The winning candidate is the least likely, and this reader saw that coming from the first page when he was introduced. (Why else was he there?) How he came to the forefront is put down to the Holy Spirit. That may have satisfied some, but not all readers I should think. It is just too easy, I am afraid and my suspension of disbelief snapped there.

Both Wikipedia and Amazon’s mechanical turk indicate several other books about Papal elections and if ever I am motivated to return to the subject there is bibliography. Indeed, Harris offers some titles at the end of the book.

All is made clear. (Irony.)

All is made clear. (Irony.)

Robert Harris is a superb writer and he brings to life an interesting array of characters, endowing many with an interior life that is rich, complicated, humane, and realistic.

Robert Harris

Robert Harris

He treated the spiritual dimension with great skill. The sincerity of the believers is given full measure and the story is richer for it. There is sin, but there are no villains.

His three volume novel about Cicero is only thing I have read, and I have read a lot about Cicero, that made sense of Cicero’s contradictions. Sometimes fiction is the best way to make sense of facts.