The author makes two broad points in this extremely well crafted study of a much maligned and seldom understood institution.

(1) The original Constitution of the United States created a federal republic, rather than a democracy. That is, democratic elections were but one part of the institutional array arrived at by compromise to create a strong but limited central government. The Electoral College was born of that desire to refract public and popular opinion, not merely transmit it, though the selection and timing of the Electoral College vote which were products of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century manners, morēs, and technology.

(2) The democratic impulse has since grown and grown in step with the growth of the legal and moral authority of the chief executive, the President, since 1789. The rhetoric of democracy, the reality of corruption in some legislatures, and the speed of communication technology have combined to make the democratic presidential election the highest expression of the Constitution, leaving the Electoral College a relic of the past (and the Supreme Court an annoyance to be tamed through appointments). Or so it might seem to a casual observer.

The author makes very cogent arguments for the continued importance of the Electoral College, though of necessity each argument ultimately rests on speculation.

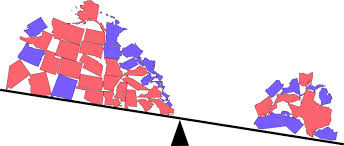

The first argument is that the need to secure a majority of Electoral votes means a winning candidate has to gather support across the nation. Without the check of the Electoral College, astute candidates would concentrate their efforts where the voters are: California, Florida, New York, Texas, Illinois, and Pennsylvania. In those states they would further concentrate on the big cities. This assertion is not entirely speculative since this concentration occurs now, but as the author demonstrates it is currently balanced by the need to distribute effort.

The second argument must needs be speculative. It is that the Electoral College, by aggregating support from across the country, drives candidates to the middle range of opinion to find that magic 50% + 1. It is an institutional disincentive to extremism. In so doing it is also a buttress to the two-party system. While third party candidates have had impact – Ross Perot, Ralph Nader, and George Wallace, in particular – none has had a chance to win. The speculation is that without the need for a majority in the Electoral College, the field of candidates would increase. In 2016 we could then imagine Bernie Sanders running as an independent and Mitt Romney acting on his words as another independent candidate, along with Hillary Clinton and Trump Donald. Plus that man who has never heard of Aleppo. Well, so what?

With more than two high-profile candidates, it is likely that none of them would secure an overall majority of popular votes. If the slate in 2016 were Clinton, Romney, Sanders, and Trump that certainly seems likely. One of the four would have a plurality, that is, more votes than any other single candidate, but in such a crowded field it is unlikely to be a majority, and there would also be other minor candidates draining votes, say a resurgent Al Gore, to pick an amusing example.

A Constitutional amendment would be necessary to anticipate such a possibility. The Constitution does have provision for a contingent election where no candidates has a majority in the Electoral College; a joint sitting of Congress would choose from among the top two candidates. Would such a contingent election, a likely outcome of the democratic impulse, be democratic? Moreover, the question might be which Congress? The one that exists or the one elected coincidentally with the Presidential election? There are many complications here because the House is elected in whole while the Senate only by thirds.

In fact, Congress in a contingent election would act as an Electoral College and in so doing would subordinate the executive to the legislature. The scope for politicking in this eventuality is unlimited and nearly unprecedented. By the way, there was such divisive four-way race despite the Electoral College in 1860 and that precipitated the Civil War though Abraham Lincoln won sixty percent of Electoral votes his support was purely Northern, and his popular vote was forty percent, far ahead of the second place. Not an example to be repeated to be sure, but not discussed in these pages either.

The author also suggests in passing the scope for recounts and other ex post facto contests would be greatly expanded in the search for a national majority or plurality. This does seem likely with the result that vote counting could take longer and longer and the incentives for disputes, political, moral, and legal, would increase, as per the 2000 election, and be settled perhaps by a court. Hardly a democratic outcome.

Note well, there is no constitutional provision for a chief executive once the incumbent’s term expires in January. Vote counting and resolution could go well beyond that date. I can add to the speculation by supposing that there would be some who would try to influence the outcome by affecting eligibility laws.

The author also points the numerous lacuna in the United States Constitution, which ought to be fixed long before the Electoral College is changed. Here are a couple to consider.

Let us imagine Trump Donald wins the November 2016 election with a sizeable majority of popular votes that guarantee sufficient Electoral votes. Then a week later, after the poll is official, he dies. (Those voodoo dolls finally come through!)

Who is in line to be the next president? No, not his Vice-Presidential running mate because he did not get the votes for president and in any event he has not been sworn in, and the Constitution does not recognise the political parties so the Republican Party, much as it would like to do so, cannot put up David Duke instead. There is no remedy in the Constitution.

Here’s another. A triumphant Trump survives and the Electoral College meets in December and gives him a majority, while Congress is in recess. Then he dies the day after. Again there is no path to a president. His Vice-Presidential running mate has still not yet taken the oath of office and has no claim on the office of president, though he would have a legal claim to the office of Vice President as explained below. The Electoral College results only become constitutional when they are submitted to and accepted by Congress in January. There are measures for emergency sessions, true, and the sitting President can call for an emergency session, but it is too late if Trump Donald died.

In this scenario Trump’s Vice Presidential running mate would have a claim to be Vice President because on inauguration day, the Vice President-elect is sworn in first in the Senate. This practice evolved to insure that the Vice President was available should the President-elect die on the spot. This provision came into being after an assassination attempt on Andrew Jackson. Swearing in a Vice President without a President, there is no constitutional or legal justification for that. Nor is there any legal or constitutional provision for another election. Still less is there any constitutional or legal framework for a caretaker government by the incumbent whose term expires on inauguration day.

No, commonsense would certainly not prevail.

In the polarised and poisonous miasma that now suffocates Washington, D.C. every step would be contested ad nauseam, and the struggle for supremacy among the talking heads would fan every ember into a conflagration. Imagine Murdoch’s Organs as king-maker. Shiver.

The author concludes that the Electoral College be kept pretty much as it is, but that the casting of its vote be made automatic on the majority result in each state, on a winner take all basis. There is another complication here for a later date.

It should be kept, she argues, because it bolsters the two-party system which in turn moderates public opinion to the centre from the extremes and it promotes a nationwide campaign. Though it cannot absolutely guarantee to deliver each of these benefits with certainty, it does provide palpable incentives for each, as was the original intention of its creation.

The author also supports the winner-take-all approach to Electoral votes so that if Trump Donald wins 50% + 1 of popular votes in New York state he gets all of its Electoral votes. This is currently the law in forty-eight states. The winner-take-all rule makes the fewer votes of the smaller states more valuable, goes the argument. As poker pots are won in all and not split by the value of the hands of the respective players, so are Electoral votes. Yet it is two small states (Maine and Nebraska) that have split their few votes according to congressional districts, a quirk that allowed Barry Obama to win one Nebraska electoral vote. Amazing. The winner-take-all provision magnifies the winner’s support and that is supposed to increase legitimacy. Yet to many these days it does the opposite; it decreases respect for the process by inflating the margin of victory contrary to the popular vote per 2000 and 2016. The author is silent on this point.

By the way, official results are those certified by each state attorney-general as compliant with state laws. There is plenty of room in this process for dirty work. Check Florida for recent examples where lawsuits go away with campaign donations.

The author does not consider Facebook as an alternative to the Electoral College. A glaring omission that is. The candidate with the most friends and then the most likes wins! There are some entries on Facebook about the Electoral College but none to be recommended.

While the author refers to many historical examples, in none of them does the Electoral College save the day. Yet that is the master narrative. Hmmm.

Tara Ross

Tara Ross

The book is very well written and very thorough. The prose is clear and specific. The approach is analytic. Having said that the author’s preference for retention of the Electoral College is apparent from the start.

There is more to the book and I may do another comment, but I wanted to publish this one before the United States election, so here it is.

An aside for Australian readers: The preferential ballot in Australia has the same function of creating and magnifying a majority, even creating one where none existed. This fiction is enthusiastically embraced by Australian voters, despite the anomalies it sometimes creates through elaborate preference deals that give parliamentary seats to candidates with few first preferences. In some ways it is just as wacky as the Electoral College but it is an article of faith not to be questioned.

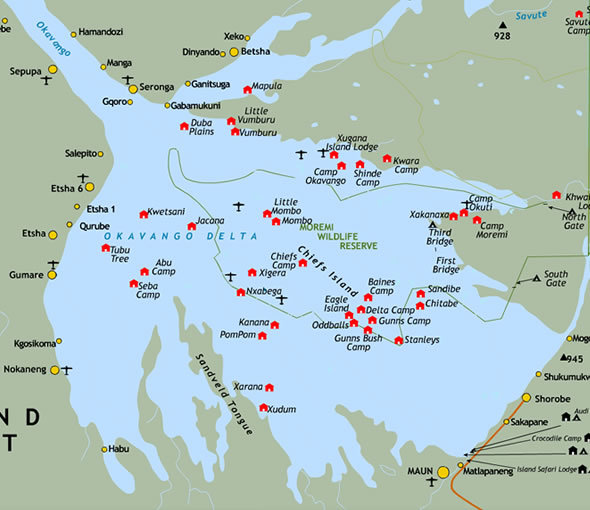

The red dots are tourist camps on higher and drier ground.

The red dots are tourist camps on higher and drier ground. ‘Don’t fed the crocs. Keep your hands and feet in the boat!’

‘Don’t fed the crocs. Keep your hands and feet in the boat!’ Michael Sears and Stanley Trollop

Michael Sears and Stanley Trollop

Vaseem Khan

Vaseem Khan

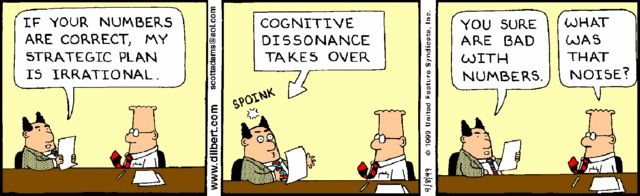

Dilbert knows.

Dilbert knows. Rather like a Ted talk. So much show, so little go that one dare not admit it.

Rather like a Ted talk. So much show, so little go that one dare not admit it. Leon Festinger

Leon Festinger

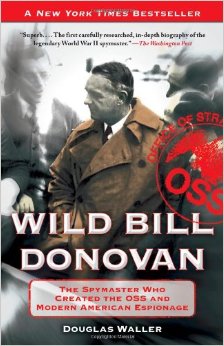

Douglas Waller

Douglas Waller

Ford Point in the foreground where the horse is. I have stood right there and looked for the stagecoach with John Wayne in it.

Ford Point in the foreground where the horse is. I have stood right there and looked for the stagecoach with John Wayne in it. Ship Rock in New Mexico near where Bernie and Joe live and work.

Ship Rock in New Mexico near where Bernie and Joe live and work. Anne Hillerman

Anne Hillerman

Neil Gaiman

Neil Gaiman