The further adventures of Ruso, medical officer late of the 20th Legion, and his British wife Tilla, and their adopted daughter Mara.

A turn of fortune brought them to the capital of the world, Rome. Tilla resisted leaving Britannia, but needs must and off they went.

She found Rome even more awful than she expected and her expectations were very bad. For his part, once there, Ruso cannot quite remember why it seemed a good idea to go to Rome. Tilla heroically resists saying ‘I told you so’ for as long as she can. Not long that.

The disorder, noise, smells, expense, rudeness, violence, are just some of the vita Romana. Little has changed since then, to be sure.

The patron who sponsored their migration, luring Ruso away from his army sinecure, where he had long since worn out his welcome, is likewise not sure now that it was a good idea. There seems to be nothing for Ruso to do, and Rome is full of doctors, snake-oil salesmen and, for that matter, saleswomen, faith healers.

However when Doctor Kleitos is called away to the country, Ruso is nominated by his patron as the locum. Excellent, thinks Ruso, because the quarters will get them out of the overpriced hovel they are renting and the surgery will generate some sesterices.

Odd though that Kleitos seems to have taken everything not bolted down, tables, chairs, crockery, and all his medical records for a temporary leave. Even odder that a dead body is delivered to the front door in barrel.

Thus does the plot thicken.

Ruso is so wonderfully vague and easily distracted, so painfully well meaning and imperceptive, technically adept at medicine and foolishly brave that he charms the reader. TIlla is so determined, impetuous, and resourceful it makes the reader wonder how the Romans ever conquered her tribe.

She sings Mara to sleep with British songs of triumph, while Ruso worries about the dosh he does not have, and puzzles over the fool’s errands his patron dishes up. What is going on? Then there is that dead body….. It has nothing to do with them but it has put a curse on the medical practice, compromised the patron, and generally gummed up the works. Like it or not, they are going to have to figure it out.

Apart from the historical setting the most amusing elements in these novels is the by-play between Ruso and Tilla, man and wife. At one point, amid the confusion, she agrees with him, calls him wise, and meekly defers to him on some point. He puffs up and as he leaves, he starts wondering if she is ill. What else could explain this submission.

Ruso has his own moments. When an accident causes injuries on a building site there is the competent legion doctor performing triage, applying tourniquets, snapping dislocated bones back into place while the dust is still flying. When quiet returns so does the self-doubt, regret, and weakness that dog his steps.

Tilla may be small and foreign, but she has learned to survive, as some heavies come to extort money discover to their regret. As she seems to drop to her knees to beg mercy, she is achieves the angle of attack!

Ruth Downie

Ruth Downie

This is the latest in a long running series. The learning is worn lightly but there is a mountain of historical research in each book that is made intelligible to the reader. It must difficult to maintain the momentum and to reiterate the freshness and vitality of the two principals each time, but so far, so excellent.

The author starts with a blank screen and the silent expectations of readers. The days and months pass and finally there is a plot, a story, and a manuscript. Then the real work begins of whacking it into a novel.

After all that work, one reviewer on Good Reads has this to say:

‘A non-offensive and not super engaging story about the Medicus and his family in Rome. It was a fine time passing book, but not one I would recommend.’

I would give that remark one star (*) and say it is lazy, inept, and self-indulgent. To sum it up in English: ‘An inoffensive story that did not engage my attention but I did read it.’ This reader’s recommendation is something I can live without.

Author: Michael W Jackson

Finland, Mannerheim, structure, and agency

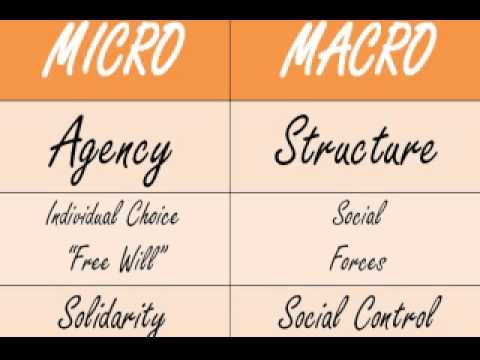

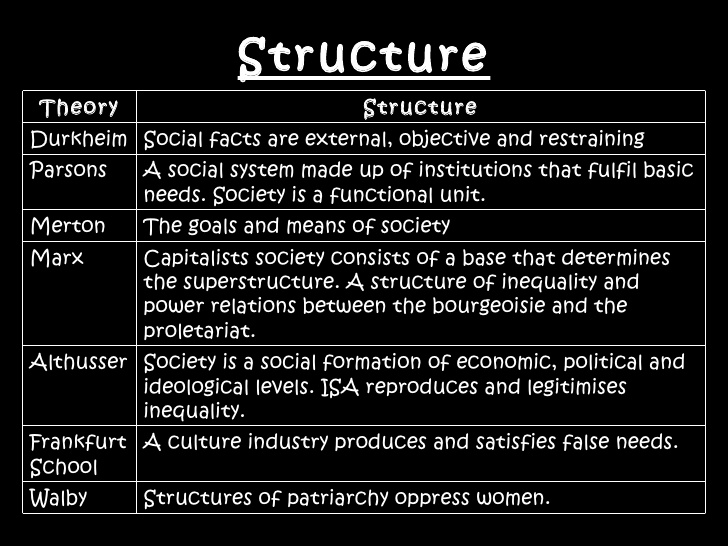

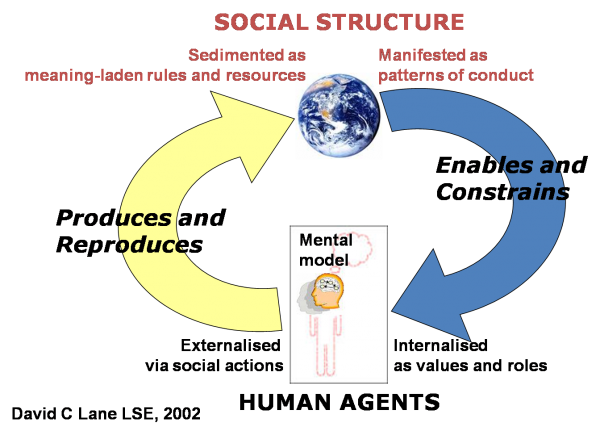

Structure and agency, that famous double play combination for Team Social Science, came to mind reading about that extraordinary individual, Gustav Mannerheim.

The social sciences as a whole and each separate social science, like my very own political science, rests on the verity of structure über alles. Structure is both all around us and sometimes difficult to detect at the same time.

The challenge is to reveal structure hidden by the drifting sands of time and circumstance. To see structure in the myriad of details of social life requires detail and imagination, like seeing a constellation in a sea of stars, but it can be, it is, done. Every social scientist has sworn that faith at least since Emile Durkheim’s monumental book ‘Suicide’ (1897). For those who skipped Sociological Theory, in that study Durkheim demonstrated beyond doubt that most private and final act of suicide traces back to social structure. The argument and evidence still dazzle a reader.

Yet it is also surely the case that most social scientists think of themselves as agents. The preacher is always beyond the testament. That is the chink in the intellectual armour. Karl Mannheim made that auto-exceptionalism explicit when he spoke of free-floating intellectuals clustered in cities who are in but not of the milieu around them. Vanity thy name is called once again. Many convoluted books have appeared trying to unite the two from Jurgen Habermas’s impenetrable tomes to Anthony Giddens unreadable tracts. Each sets out to make the obvious simple and instead makes it unintelligible. Biography is cold, crisp air by contrast to the stale, hot air found in those pages.

Per structure, if the individuals who made the first steps in developing photography had not done so, others would have made those or other developments that would lead approximately to the same technical advances. That is easy to believe in the middle of technological developments where many hands are at work trying many things as was the case with photography. Or, say, the discovery of DNA when many scientists around the world were closing in on it in a race of sorts. It is less easy to believe in the history nations.

Yet according to structure had Gustav Mannerheim been killed in 1916 on the Polish front while fighting the Germans in World War I where he was a general in the Tsar’s Russian army, some how another(s) would have filled his shoes, or some very like them, and the story of Finland would have played out pretty much the same. If Winston Churchill had been killed crossing the street in New York City in 1929…. If Adolf Hitler had died of typhus as an infant….

Ergo, no single individual, no agent, is decisive. Structure makes us but we do not — individually — make structure. Collectively, yes we do make structure as much as it makes us but not individually.

Structure is not quite determinism but the transposition offers the easiest exposition.

Even allowing for the biographer’s preoccupation with the subject, it is hard to believe that there was anyone else could have done what Mannerheim did in 1918-1919 and again in 1940-1944. Certainly that is what both his allies, friends, associates, onlookers, and enemies thought. He was as singular in the history of his country as Napoleon in France, Stalin in Russia, Churchill in England, or Hitler in Germany.

Without Mannerheim the history of Finland would surely have been different. Though I am sure revision pygmies have made careers out of cutting him down to their size, in fact, he will endure and they will not.

Star Trek: Beyond (2016)

This is Year Fifty. It all began in September 1966 and I was there to see it on that night in September. All Trekkies will have to see this, whether they like it or not.

What’s to like?

The cast members are superb simulacra of the Originals. That is partly looks, assisted by make-up, but also mien, accent, and attitude. The actor’s craft is to inhabit another person and they do it with ease. Bones is perfect and so is Kirk. Spock is more nebbish than the Original. Uhura is more wonder woman, and Scottie is more excitable, but these are quibbles.

The distribution of lines and incidents to the ensemble cast of the crew. Scottie, Sulu, Uhura, Spock, Bones, all have more than one moment in the camera’s sun. Only Chekov misses out, in my memory. It is not all about Kirk, as too many episodes of the Original were.

There are some zingers to be sure. Throw aways lines like ‘they say it hurts less if it is a surprise.’

The women hold their own. Uhura may answer the phone once or twice but she also delivers some surprises.

Jaylah’s literal-mindedness was amusing. Though good to have on side in a fight, Jaylah seems to be there mostly for the make-up.

The idea of heavy metal music can be used as it is in the movie was marvellous. I am trying to steer clear of a spoiler here.

The explicit tribute to the Originals in the last scene with Spock was humble.

What’s to not like?

The repetitive shoot ‘em ups are incomprehensible and pointless and there are many of them, at full volume.

The holes in the plot are sufficient to pass Africa through. The villain’s backstory is vacuous. The Franklin is … What’s the word, it is impossible to suspend disbelief.

The Federation’s own responsibility for its problems is a worn out motif in Star Trek but here it is again.

The variation are the returned veteran was the theme in the predecessor (‘Into the Darkness’) but here it is again in a slight re-configuration. These writers need to read more to find inspiration, say Jane Austen or Anthony Trollope to broaden the horizons and deepen the insight.

The theme about unity and strength is said a couple of times but left empty. Recalling as I do all those conversation with thesis writers where I would say integrate, e.g., Michels’s Iron Law, and the writer would say ‘But it is on page 46’ and indeed it was mentioned there but it was not developed and integrated into the text. Neither is the unity-strength couplet here. It is a case of ‘words without the music.’

The army of CGIs dispatched in the action scenes bring the franchise closer to the comic book status of Start Wars.

Kalara, the bait, with that strange head more or less disappeared from the story.

Summing up.

At two hours and two minutes it is about thirty-two minutes too long. The interest and intelligence of the story do not sustain the duration. It is out of balance.

The effort put into those CGIs and choreography of the action scenes might better have gone into the script.

What made ‘Star Trek’ a keeper in 1966 was that it was not just another shoot ‘em up on television where there were plenty others of that ilk. There were genuinely intellectual puzzles, like ‘Court Martial’ and morally challenging episodes, like ‘The Devil in the Dark’ and ‘The City of the Edge of Forever.’ In its current embodiment most problems are solved with a fist and a phaser. Such a contrast to the Original, e.g., ‘Nomad, ‘Return of the Archons,’ or ‘The Doomsday Machine’ where some thinking had to be done.

The Original was made for adults and ‘Star Trek: The Next Generation’ brought that to fruition. The present version is regressing to an audience of prepubescent boys which is probably inevitable since that likely describes the filmmakers from writers, directors, and producers.

‘Needle in a Time Stack’ (1966) by Robert Silverberg

This title is a collection of science fiction short stories by one of the well-known names in the genre at its peak. In 1966, fifty years ago, a gallon of regular gasoline in the USA was 0.31 cents. Cars had tail fins. Japan was where the junk came from. Vietnam was seldom in the news. The Cold War was very cold. China was …. nearly invisible. Hollywood ruled the silver screen. Air travel was the preserve of the very rich.

Robert Silverberg’s (1935 -) stories feature automatic doors, mobile phones, automatic autos (self-driving cars), surgery that does not cut the skin, video watches, as well as the a menageries of aliens. But mostly the stories are how people think, act, and react. The gadgets are there as props and furniture, as are the aliens.

Best of all, given that in 1966 ‘I Love Lucy’ was the top-rated television show, was his anticipation of reality television with its fetish for the pain and humiliation of others. Equally amusing was the tyrannical robot diet enforcer in ‘The Iron Chancellor.’ Yes, the allusion is to Otto von Bismarck who is here combined with a diabolical Jenny Craig.

The most thought-provoking was ‘The Invisible Man,’ a rift, of course, on the H. G. Wells story but with some social and psychological insight which Wells never had.

The stories are all about 15-20 printed pages. Irony features heavily in them. Think if Rod Serling’s ‘The Twilight Zone.’

A character, usually the narrative voice, is confounded at his own game. The con man is conned. The exploitive television producer is exploited. The lord is abased before a serf. The expert on alien life forms is disgusted to meet one. The firm bureaucrat is dealt with firmly by another. There are quite a few role-reversals.

Most of us like to see the mighty eat some crow. The more so when the mighty are unworthy.

As adventuresome and imaginative as these stories are, a contemporary reader they swim in the manners and morēs of 1966. There is nothing about racism. Not even the stories involving alien beings seem to reflect on race relations.

Alike absent are women. Occasionally there is a secretary in an outer office, or budding young girls who long to be married, or a frazzled housewife, but none is an agent, an actor, These are men’s worlds. The linguist has a wife but her role is to pack his bag when he goes to meet the aliens. The doppelgänger meets several young women whose only aspiration is marriage. The dieting husband has a wife who also needs to diet, but she is but a chorus to his tenor.

Sometimes the balance of the stories fails. There is a considerable lead up to wispy, poof denouement.

The prose is fluent and confident. I re-read a couple of Philip K. Dick novels a few years ago and remember finding it hard going. Not so with these pages.

Most collections of short stories take the title from one of the stories, usually the longest or the one placed first. That is not the case here. The title stands apart.

Robert Silverberg

Robert Silverberg

This copy emerged from a box in our recent move. Kathlyn McNeil bought it for 0.80 cents Australian in 1966. In those days the back cover had prices of Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, South Africa, and East Africa. Its pages have yellowed but the paperback spine remains bound.

When the deportations begin….

When a President Trump Donald begins deporting those he deems undesirable, will it go so far at to disinter the dead? If so, the program best begin at Arlington National Cemetery because there will be found the graves for a great many Mexicans and Muslims who died in the service of the United States, most of the recent ones in conflicts ordered by Republican presidents.

There are many more but let these examples suffice.

Least one think such a program is beyond the pale, note that it was done in Hitler’s Germany, Dead Jews in war cemeteries were disinterred and dumped elsewhere. Everything old can be new again. Though one hopes bellbottom trousers are not included.

My brief foray into the free-fire zone of Hillary Clinton elicited fevered responses from the righteous. So be it. But ensuing heat mirage may have blurred the concluding remarks about the dead. Ergo, at the risk of boring dedicated Bleaders, I reiterate those remarks above.

What’s it all about Hillary?

I was asked the other day, ‘A lot of people dislike Hillary Clinton. Why is that?’

My answer was simple. Her sin is that she is a woman.

A sin that has been compounded by her relentless ambition, since she was a junior employed by the Watergate Committee that pursued Richard Nixon to retirement. But such facts are not relevant.

The hatred that has been sown and nurtured by the Fox News and its allied ‘paths’ (a term that includes both sociopaths and psychopaths) for these many years has grown out of little more than hardened air.

The night she was elected to the Senate some years ago, by chance I was checking into a hotel in New York City, and when the count came on the television screen in the lobby, everything stopped. In the silence the announcer said Hillary Clinton had been elected and the lobby erupted in cheers from hotel staff and guests. It was completely spontaneous and general. I was surprised but she certainly had dedicated supporters that night.

She does not have to do anything to attract the vitriol and innuendo. Being is enough to provoke the haters.

That she is thick-skinned and keeps coming back for more, merely makes the haters sharpen the invective the more. Hypocrisy knows no bounds. Ask John Dennis “Denny” Hastert.

She has also learned how the system works and she has focused on making it work for her. Another of her crimes.

If it needs to be said for the back row, ambition, a thick-skin, and focus in a man are a virtue, but in a woman….

Grotesque but true, and nothing now will make it go away. Parking tickets, speeches to Girl Scouts, email at Christmas, shopping lists, everything has been ransacked for something and when nothing is found that is taken to be proof of deceit.

Barry Obama’s sin is greater. He is black. That is the ember that burns throughout the haters to which Trump Donald is now giving voice and license. All the smoke has created the fire.

The final sin that unites Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama is that they are Democrats. Black, woman, and Democrat are the three horses of the apocalypse for Fox News, Murdoch Organs, and Haters United, i.e., the Republican Party.

To mention that Republican nominee, I wondered if the deportations bruited of Muslims (Arabs) and Mexicans will include all them who have been killed or maimed in Vietnam, Somalia, Iran, Korea, Laos, Cambodia, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Will the next Republican administration dig up dead bodies, starting at Arlington, and deport them, along with the cripples and deformed who wore the uniform. Let it be noted that many of these dead were killed at the command of Republican administrations.

It was amusing the other day to read Republican sage William Kristol bemoaning the rise of Trump Donald, since Kristol was one of the laboratory assistants to his father that converted the Republican Party into the Frankenstein it has become. Having sown, this Igor now reaps.

Even more amusing was Kristol’s generalisation that historically Republican candidates for president have been superior to Democratic ones. Such is the view from Olympus, where dwells he amid the mirrors, they being his main source of information. No criterion are stated, and facts are absent.

Does this crew of candidates make one swell with pride? Warren G. Harding, U.S. Grant, Alf Landon, Chester A. Arthur, James Blaine, Barry Goldwater, and William Howard Taft.

No doubt some of these individuals were decent men, e.g., Grant, but he was a lousy president.

‘Skeletons in the Closet’ (2011) by Jennifer Hart.

This is the first title in series ‘The Misadventures of the Laundry Hag.’

Maggie Phillips, a Georgia peach transplanted to Taxachusetts, is a domestic engineer to her retired Navy-man husband and two growing boys. Neal, the Husband was a SEAL, and knows a thing or two. He works IT three twelve hours shifts a week, leaving him plenty of time to pitch in when Maggie needs help.

Boredom with the duties of domestic engineer and the need for more cash than the navy pension provides, these together lead Maggie into business of house cleaning for the rich and fatuous around Boston. There she finds a closet…..

They moved to Boston because Neal’s parents practice law there: His father with patrician indifference and his mother with furious determination. When these two invite themselves, and their own guests, to Thanksgiving dinner with Neal and Maggie, the pressure cooker goes on. The parental guests are important clients of the mother-in-law and she demands that all be perfect. The father-in-law just likes to watch the mayhem.

It is a nice set up and despite the context, mercifully free of catalogue descriptions of all clothes and furnishings except where they figure in the plot or distinguish a character. There is plenty of repartee, and some of it is clever.

Jennifer Hart

Jennifer Hart

Maybe the mix is too rich with the wayward brother bobbing up and the boys; schoolwork. Yes, life is like that but fiction needs focus.

I listened to it in an Audible production. The accents sounded authentic to me.

‘Barney Frank’ (2009) by Stuart Weisberg

Barney who? Barney Frank, the nemesis of many a blowhard on Capitol Hill where they flourish. He was often to be seen on C-SPAN boring into witnesses, preferably a stooge for a vested interest like automobile manufacturers demanding more subsidies, junk bond owning banks there to defend executive bonuses, or a Republican administration flunkies sweeping dirt under carpets. He went at each as the prosecuting attorney cross examining a well-known villain.

Only the most truthful and well-prepared witnesses limped away intact.

The Frank Test became a coin in Congress for thirty years. If Barney Frank could not find fault, then it was good to-go.

Mr Frank was born in 1940 in Bayonne, New Jersey where his father owned and ran a truck stop. His parents once hosted a reception for Eleanor Roosevelt in their home when he was a boy. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1981-2013. He basked in the label, ultra-liberal.

His political career began when, a graduate student in political science at Harvard, he got involved in Kevin White’s mayoral campaign in Boston. Frank, whose graduate work was not compelling, found politics very compelling and worked night-and-day for the White campaign, and emerged as one of its masterminds. He was always there, always picked up the phone, always remembered someone who could help, always found what was lost, always thought of something to try… Reliable, dependable, creative, and accessible, he made himself invaluable.

When White became mayor he had obvious ambitions for higher office and spent most of his time in that pursuit. That left his de facto chief of staff Barney Frank in the office to take the calls and make the calls. (I say obvious because some time later when I spent a semester at Harvard on leave I observed the White administration from across the Charles River in Cambridge and White’s disintegrating ambitions were a spectacle.)

Frank found politics much more interesting than political science and did not complete the graduate degree. He took time off from city hall and worked for a congressman in Washington D.C. for two years and liked what he saw in the legislative world.

He kept solving problems at town hall, meeting more people, impressing others with his thick skin and tireless efforts. He ran for the Massachusetts state legislature, which has the quaint name of Massachusetts General Court, and won a seat in the lower house.

For eight years in the statehouse he advanced one liberal cause after another, e.g., low cost housing, abortion, civil rights, school bussing, and the like. Many people spout liberal causes and are satisfied with that, and Mr Frank, too, likes to spout, but unlike many others, when the spouting was done, he took committee work seriously and applied himself both the substance of reading and evaluating submissions, proposals, and evidence, and in learning the rules of procedure. He also employed researchers to dig and dig they did. Accordingly, he scored some publicity coups and some legislative successes.

A large, disheveled, left-handed Jew, representing a Back Bay constituency made good copy any time, and he attracted publicity. Plus he has a motor mouth, and a quick wit. On slow news days journalist knew they could get copy out of him, and he obliged on his terms. (The Back Bay is home to the purest, whitest, richest, most closed colonial aristocracy of Massachusetts. Upstarts like the Kennedys were barred from this society, having to make due with Brookline.)

At the time many liberals liked spouting about foreign affairs, but Mr Frank went on the banking and finance committees because that was where the money came from to fund liberal causes like low-income housing. The first thing he realised was that inefficiency and sweet-heart deals with labor unions made spending on liberal causes impossible. The first of his many crusades was to cut waste government where he made allies with conservative Republicans, and antagonised unions. The battles with the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority became legendary. He rode the MBTA every day and charted its many failings against its exorbitant running costs and outlandish work practices, outlandish even by Australian standards. His spreadsheets on cost per customer mile traveled compared to other cities entertained viewers on news programs for weeks on end.

He also accepted no-win assignments on other committees where his vote would alienate some Democratic constituencies, like organised labor, but since he had already alienated them, he did the duty, sparing other colleagues the pain. They then in turn owed him favours.

In the financial crises of the Junior Bush years he was a Cassandra, warning of trouble ahead to be ignored, and then later as the wheel turned he was blamed for causing the trouble by predicting it. In hindsight Republican Bush administration officials even blamed him for not stopping them. That is political logic!

There is no doubt he was a one-man brains trust in Congress with some memorable turns of the phrase who had no small talk and no time for normal pleasantries. He was always all business all the time, right here, right now. Nor was he easily discouraged: Blunt, direct, acerbic, and well prepared. Here are a few examples.

1.This bill is the legislative equivalent of crack. It yields a short-term high but does long-term damage to the system and it’s expensive to boot.

2.People might cite George Bush as proof that you can be totally impervious to the effects of Harvard and Yale education.

3.Moderate Republicans are reverse Houdinis. They tie themselves up in knots and then tell you they can’t do anything because they’re tied up in knots.

4.They have become so attached to their outrage that they are outraged to lose it.

5.Southern racists were able to protect murderers only because their legislators exploited fears of federal power.

6.For those like Ben Carson, who just announced that it was a choice, I do want to say at 14 I did not choose to be a member of what I thought was the most hated group in America.

7.They can vote for every possible war that comes along and still be pro-life.

8.The runner slides into home with a thousand dollars in hand as a contribution to the umpire but the money will not effect the call….that is what we say about campaign contributions.

9.I’m left-handed, Jewish, and Gay, there is no majority I belong to. Well, maybe the overweight.

When an amendment he presented failed in committee, he re-worked it and presented it again, and again, and again. In so doing, he became a master of procedure. He also spent all hours trying to talk others around to his way of thinking. This talk, talk, talk reminded a little of the loquacious young George Wallace.

The descriptions of the joint House and Senate committees to harmonise bills and of the ad hoc committees called by President Bush to find common ground are delightful. In them John McCain comes off as a driven man who knows he has to be involved but has nothing to offer and takes his own sweet time in doing that. Bush Jr appears well meaning but lost.

But the severest criticisms are for the technicians Henry Paulson at Treasury and Benjamin Bernanke at the Federal Reserve whose faith in their own technical prowess led them to overreach.

On the other side of the coin Senator Barack Obama comes across as extremely able, well versed, and ready to compromise if it will do some good. While McCain was determined to be the centre of attention and when he got it, he had nothing to say on the subject, Obama was content to wait his turn and when it came he make concrete proposals that most could accept.

Mind, the telling is entirely one-eyed and ever partisan.

Frank’s other claim to fame is the public acknowledgement of his homosexuality in 1987. It was a long time in coming but a few years before he began telling family, friends, and then colleagues. There were whispers and finally an interview was arranged in which he would be asked the direct question to which he gave the direct answer. The double-life he had been living for years was difficult he had eruptions of temper, often directed at women, including some journalists on air. He was losing self-control and had enough sense to realise it. It would be better, he thought, to clear the air and let the chips fall. This is the longest chapter of the book and more interesting. I flipped through many of the remaining chapters at light-speed.

For a time his private life became very public, and the news was not always good. He did some stupid things. Hands up all those who haven’t.

Frank seems to have found happiness.

Frank seems to have found happiness.

The book is replete with anecdotes and much play-by-play description which does nothing to illuminate the man and his formative experiences. Barney walks on water through most of it. I stress the uncritical nature of the book because it surprised me, coming, as it does, from a university press.

Stuart Weisberg

Stuart Weisberg

I chose it because of the publisher on the assumption it would be dispassionate and disinterested. Not so.

‘Wrath of Furies’ (2015) by Steve Saylor

Another entry in this long-running series. Gordianus is caught up the revolt of Mithridates VI of Pontus against the Romans in Anatolia.

His one-time tutor Antipater is in trouble in Ephesus and Gordinaus betakes himself to find out the situation.

But Mithridates has just driven the Romans off the mainland of Asia Minor and occupied Ephesus in triumph, and is secretly preparing for his really big barbecue. [Anyone who knows the history, knows what is coming, and those who are ignorant can remain that way.]

Goridnus hatches a hare-brained scheme to enter Ephesus disguised as a Greek and rescue Antipater. The whole scheme turns on Gordianus keeping his mouth shut, since his Latin accent says R – O – M – A – N! And all Romans are persona non grata in Anatolia. Gordianus is usually a motor-mouth, and will most assuredly blurt out something, sooner or later.

Even before he gets there the plan unravels. It seems just about everyone he meets en route from Alexandria, to Rhodes, to Ephesus knows his plan. In short order, he is suborned into acting as a Roman spy.

Meanwhile, he worries about his ailing old dad back home in Rome, which is embarking on another round of elite circulation via murder and mayhem in a civil war. Elections might not be cheaper but they are marginally less destructive.

The to’ing and fro’ing in the eastern Mediterranean from Alexandria to Rhodes to Ephesus is amusing, but Gordianus is just too serious for me. Worry, worry, worry, he is always worrying and in the brief moments when he is not worrying, he is lusting after his wife to be, Betheseda. He is not the life of the party is Gordianus. There is always a dark cloud over his head. He takes himself and everything about him far too seriously. I pined for Decius when I read these. Where is that wastrel with a bad word for everyone? (He is the protagonist in John Maddox Roberts’s SPQR series.)

This entry in the series seems laboured, a short-story bulked up with long passages from Antipater that do not advance the plot, deepen characterization, or lend much colour, though they show the author’s ingenuity to be sure.

Steve Saylor

Steve Saylor

And the denouement with the Furies is likewise ingenious. The Furies are a bad crew with plenty of wrath to go around.

We spent a day in Ephesus in 2016 and so I had to read this title.

The library.

The library.

The sacred way.

The sacred way.

The amphitheatre.

The amphitheatre.

Ephesus is a remarkable site for the preservation of so much of an ancient city on such a grand scale. Sooner or later some mad men will no doubt blow it up to prove their manhood to….themselves, since no one else cares.

Morgue Drawer Four (2014) by Jutta Profijt.

A rollicking krimi with a pair of mismatched buddies, one an extroverted sleek lowlife car-thief with a four letter-word vocabulary and the other an introverted roly-poly PhD scientist in Cologne Germany.

Pascha is a rev head who loves cars, and stealing them is great fun, the more so getting paid to do so. Then one night after stealing a particularly desirable rocket car, on order from the Russian mafia, he finds in it…. Something he should not have.

He pays for his discovery and that brings him into contact with Martin, the super nerd. Their efforts to communicate and, reluctantly, to cooperate are a hoot. One is street wise to the Nth degree and the other equally book wise.

With false starts, snits, and pouts they slowly combine to find a killer, and find both more and less than they bargained for. Along the way they come to respect the assets each brings to the mission. The setting of Cologne, that cathedral city in Germany, offers much to’ing and fro’ing around town. There is some travelogue as each shows the other his haunts.

It is hard to say more without a very large spoiler.

This is the first in a series and I hope the author can keep up the joie de vie.