Bleaders, today’s lesson concerns those krimis that I cannot finish. There are several varieties filed under the heading UNFINISHED, and I have commented on some specimens earlier, like those in which everything is written in the present tense, flashbacks, flashbacks within flashbacks, back stories, etc.

That has become a deal-breaker with this reader. One weekend I read a newspaper review of book that interested me, and I was about to order it, when in the last paragraph the reviewer said that this historical study was written entirely in the present tense which the reviewer found confusing and distracting. Amen! I decided I could not read a 400-page book on an historical subject in the present tense, too hard on my teeth. (Tooth gnashing, grinding, and gritting while reading is not recommended by dentists.)

Books described as Thrillers almost always suffer from One-tense-itis, or Present tense-itis, not sure which of these neo-logisms I prefer. (I do know I prefer the hyphen [-] in neo-logism though WORD’s autocorrect does not.) Tangent completed, now back to today’s subject.

There then are IKEA krimis.

Many, many krimis read like catalogues where every article of furniture and clothing is described in detail, from pencil stubs to curtin material as the protagonists move around and meet people. Page after page is spent on fabrics and furnishings in some combination of Martha Stewart with Land’s End and IKEA catalogues, and as always at first I read it thinking that it either sets the scene or relates to, in a manner yet to be revealed, the plot, but no, all too often it is just what it appears to be, padding.

Pain in the Back-story. In the same krimi is often to be found back-story-itis, another virus of the genre, in which each character from taxi drivers, to receptionists, to passers-by are introduced in such detail that an innocent reader like me thinks the character must be important and I should pay attention because later that seemingly incidental character will figure in the plot, but…alas, no.

As in many other art forms, the primary audience seems to be other writers (perhaps, on professional awards panels), and not readers, and so the author displays the creative ability to generate backstories for everyone. Ugh! Padding by another name.

Of course, in this, as in so much else, I am in a minority, because the very books I have in mind are described as best-sellers, as great works, lionised by authoritative sources like the ‘New York Times.’ I struggle to forebear from naming titles but they have been many over the years, and I recently struck another one.

This latest example catalogues fittings, furnishings, and clothing without end, and to no end. In parallel the historical settings, which is what captured my initial interest, was treated as a one-dimensional.

The action, such as it is, takes place in Washington D.C. at Christmas 1941, and yet to all the participants in the story the war is all but won because the Germans are stuck in Russia. Huh? Yes, Germany invaded Russia in June 1941 and by December it was no longer advancing, but the crucible of Stalingrad was fought between August 1942 and February 1943 and that was the first major defeat.

Likewise the book also makes the German V-Rocket program at Peenemünde much more developed in 1941 than it was, and also has the Germans desperate for these secret weapons in December 1941!

To top that there is also a reference to kamikaze Japanese pilots in December 1941 but these attacks began in October 1944 when the Japanese were desperate. See what I mean. I stopped reading after about sixty pages.

The result was overwritten with a cast of historical characters, and undercooked with the historical context half-baked.

Though I was much interested by the period and the historical characters I just could not wade through more and more description, while gritting my teeth at the useless catalogue combined with historical mistakes. This book is a ‘New York Times’ bestseller published by one of great New York City publishers and part of series. Conclusion? Different jokes for different folks. Different facts for different….

Author: Michael W Jackson

‘The Disappeared’ (2002) by Kristine Rusch

An adult and thought-provoking sci-fi krimi. Recommended for adults.

I found myself squirming several times when reading it, tempted to put it aside, but then I realised it was getting under my skin and that was the point. Chapeaux!

Moreover the characterisations of the human protagonists are credible and the plot twists and turns follow the two rules of Sherlock Holmes: there is a logical explanation to everything and nothing is as it seems. That all adds up to a four-star review.

In a future universe there are many species who trade and cohabit the same planets with multi-cultural laws to regulate dealings and to settle disputes. The distant Multi-Cultural Tribunal issues absolute and binding rulings and warrants and it falls to the local police to enforce them, no questions asked.

Many misunderstandings arise in business transactions and in cohabitation, and there are many active warrants, which never expire. The punishments the other species apply are, well, inhuman. For several of the species apprehension of a violator is a matter of honor and no effort or expense is spared in pursuit. In some alien legal codes, ignorance is no defence. A guilty mind is not necessary.

One generation of entrepreneurs sees in this situation a market gap. Secret companies emerge to help those targeted by a warrant to disappear (and start a new life elsewhere), a relocation service for the guilty, not for witnesses.

There are many sources of tension in the setup. There are several mysteries for the police to unravel. Negotiations with two separate sets of aliens each sensitive to the least cultural slight. There is the Earth Alliance government, remote and inaccessible, for which keeping the peace by adhering to the strict letter of the Multi-Cultural Tribunal warrant is paramount. The fate that awaits those apprehended does not bear thought.

The more so because several of the species in the Tribunal act on inter-generational justice. Like Chinese emperors of old and North Korean dictators of today, they have justice to the third, fourth, fifth degree, or more. Huh? That means the punishment often falls on relatives of the culprit, relatives who themselves did nothing and may not even know the culprit. For those who shelter from the news, it is common in North Korea for the sins of the father to fall alike on daughters and grandsons. When the father is executed so are his children and grandchildren to eradicate the line. Now imagine being an officer who rounds up the babes in arms for execution.

In this novel one of the felons to be surrendered is a baby. Another is a woman who cut down a tree, only later to be told it was a sacred relic. In the law of that alien world ignorance is no defence. Still others did in fact kill a member of another species in a drunken fight over money. And so on. All of the felons in this novel are guilty but that does not make any of it easier.

All of this comes to a head because a second generation of entrepreneurs has emerged and decided to increase value for shareholders by selling-out the disappeared ones to their pursuers.

While it is illegal to help felons disappear, it is perfectly legal to sell them out.

What a beautiful scheme. The credits flow in drowning out the screams of those who disappeared and now are found. Disembowelment, babies surgically modified to become alien, condemnation to mortal slave labor, or shot on the spot are among the punishments for the humans apprehended, all compliant with the ruling of the Tribunal. The job of the local police is to hand over the felons.

Those who had successfully disappeared for decades are now sought and arrested. The human police execute the warrants of several alien species on a Moonbase. So many that they cannot keep up. One asks why low level police officer negotiate with aliens, but the answer is perfectly sensible bureaucratic logic. No more senior official wants to get involved in such distasteful and explosive business, so it is shoved down the line. That will be familiar to anyone who has worked in a large organisation.

This is the first is a long-running series.

K. K. Rusch.

K. K. Rusch.

It is well written though I flipped some pages quickly as there is nothing special in much of it, and too much musing by some of the characters for my taste, but mercifully shorn of mindless descriptions that bedevil so much of the krimi genre these days. The dialogue is functional. The author does not try to describe the aliens apart from some vague outlines, the Rev, the Disty, and the Wynin. Just enough to make clear that they are alien, not humans with heavy make-up. That is altogether an intelligent decision.

I particularly liked the senior investigating officer DeRicci and her one-way ticket approach, and the Retrieval Artist in the last pages. The last scene was a surprise and a nice coda to much that went before.

When I read the title ‘The Disappeared’ my first thought was all those who have disappeared from military regimes in Latin America, Chile, Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela, and…..

A sobering reminder that there are worse governments than the local mob.

Ryszard Kapuscinski, ‘The Soccer War’ (1986)

A unique journalist this, as Poland’s one and only foreign correspondent for many years he covered the world of Poland’s allies in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. His extended essay ‘The Emperor’ (1989) on the reign of Haile Selassie in Ethiopian is nonpareil.

The insights, the wit, and desiccated humour all stay with the reader long after. Though much of it is fiction larded with a great deal of speculation it makes sense in a way the description of facts and furnishings does not.

The essays in his ‘Travels with Herodotus’ (2002) are likewise memorable. This volume is much more thematic than the compilations of his journalism in other titles. The focus here is on history and the recording thereof.

When ‘The Soccer War’ came to light among the book boxes at home I put it aside to peruse, and peruse I did. (We are still unpacking after last year’s move.)

Most of the places and events in these essays are unknown to me. I never heard of them at the time, or if I did, the memory faded at day’s end. But Kapuściński went where Poland supported insurgents, governments, or had economic interest in the nooks and crannies of the Cold War. He travelled, as he remarks elsewhere, Polish-class. [Use the imagination.]

The Soccer War was a three-month armed conflict between El Salvador (the Switzerland of Central America) and Honduras, then a brother-in-arms with Poland in the Socialist International. Though the animosities and tensions between the two countries were many and deeply rooted, the war exploded when the two played soccer for a place in the World Cup in July 1969. These two midgets were deadly serious, and several thousand people died, and tens of thousands more were displaced. In the aftermath social services collapsed in both countries and many more died of disease and untreated illnesses.

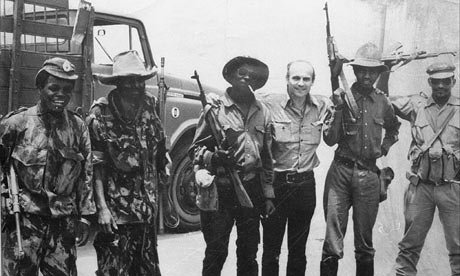

Kapuscinski with some comrades.

Kapuscinski with some comrades.

Kapuściński happened to be there and became an eye-witness, though he hardly saw anything, try as he might. Think of Fabrice at Waterloo in Stendhal’s ‘The Charterhouse of Parma’ (1839). Add jungles, swamps, and a language barrier.

‘They Might be Giants’ (1971)

Sherlock Holmes has taken many forms over the centuries, none more compelling and engaging than in this eye-popper.

George C. Scott, at the height of his considerable powers, is Justin Playfair who had been an attorney of note and then a judge of discerning insight, striving always for justice in large and in small things. Striving always and never yielding, but the years passed and world seemed no more just and then his wife died. Lost of her compass, Justin shut himself away in the family mansion, for Justin has many dollars, and became….a reborn Sherlock Holmes, complete with period costume, laboratory, and (a poor) Brit accent. He secrets himself away in the house for months at a time in a waiting game with Professor Moriarty, who else, the nemesis.

Justin’s brother needs money and a lot of it soon to pay off a mobster, and sets in motion the wheels to have Justin committed to a mental asylum so that he, the brother, can take control of the dosh. He finds a compliant doctor who will sign anything for a dollar, and then needs a second expert’s signature. Enter none other than Dr Mildred Watson, played by that star of the Hollywood firmament, Joanne Woodward, a frumpy single woman with broken fingernails and an irritating manner.

Yes, Holmes has his Watson, at last! What follows is movie magic when movies still had magic.

Playfair as Holmes is a force of nature and intellect (‘I never guess!’). When she introduces herself as Dr Watson, Scott’s eyes pop off the screen; even on a DVD on a small television, he is electric.

Of course, he’s nuts, she can see that, but…. well, it takes time to be sure. He meets her, he because he wants a Watson, she because she wants a diagnosis that can be published to enhance her career. Both get more.

Scott’s march down the hall of the mental hospital is a delight to behold. Force of nature, indeed! (No spoiler. But Scott was a Marine for four years and it shows.) It gets better when, with his deductive powers, he diagnosis one of Watson’s patients far better than she has been able to do, working by the book.

It turns out someone is now out to get Scott, to settle the wayward brother’s debts, and the game is afoot.

The search for clues leads to a telephone exchange where a scene with a caller and an operator stayed in my mind for near fifty years. That is some credit to all the players, writers, and directors. When the operator turned, I knew what to expect. It was silent comment on enslavement of us all to the machine that is society, which Michel Foucault would recognize.

There is much more, but best of all is a scene and speech. which over the ensuing many years I have sometimes quoted and often recalled.

Seeking respite from the pursuing villains, Scott takes Watson to a theatre, an old broken down movie house; as they climb the stairs, she, querulous, asks ‘Why here?’ ‘Why … because they only show westerns here,’ says Scott as though naming the self-evident.

‘Huh!‘ is the learned doctor’s reply. Patiently, as to a slow-witted child, he explains why westerns are the ultimate expression of morality. It goes something like this: ‘If you look closely at Westerns you can see principles, the possibility of justice; you can see individuals who move their own lives, bringing them to the ends they deserve.’ There are no masses, no bureaucracies, no excuses. (Bring on Randolph Scott! I cried.)

There are false notes to be sure. Jack Gilford is wasted. The episode with the garden elves is pointless. The scenes of sidling are silly and without purpose. The plot is full of holes. If it is blackmail, no one seems to care. The march of acolytes at the end is fun but pointless, and the final descent in the end still seems…. confusing., incomplete, a let down. Writers sometimes just cannot figure out what to do at the end, maybe because they do not want it to end. I know, in this case, I did not either. A great trip with no arrival like ‘L’année dernière à Marienbad’ (1961).

It is a tribute to many hands that Joanne Woodward, that belle from Georgia by way of LSU in Baton Rouge, could be turned into this dowdy woman, she who melted the screen fours years later in ‘The Drowning Pool’ with that molasses accent and honey blond beauty. Here she looks exhausted and cranky or cranky and exhausted with a big city accent, and shambles around like a lame department store window mannequin. She has many other credits, of course, and I mention a few for the sheer pleasure of calling them to mind: ‘The Long Hot Summer’ (1958), ‘The Sound and the Fury’ (1959), ‘The Fugitive Kind’ (1960), ‘Paris Blues’ (1961), ‘A Fine Madness’ (1966), ‘Rachel, Rachel’ (1968), ‘Winning’ (1969), ‘The Effect of Gamma Rays’ (1972), the list goes on.

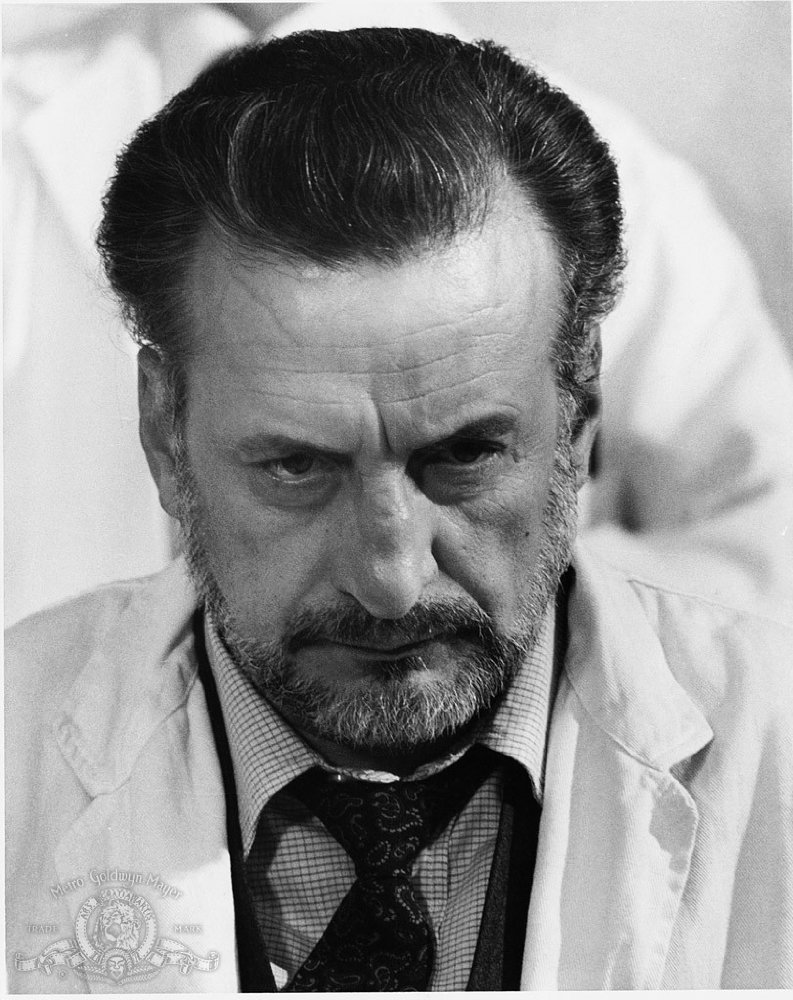

Scott, he too from the South — Virginia, was never better, and that is high praise. Among his remarkable performances was the prosecuting attorney in ‘Anatomy of a Murder’ (1959) who was so smart that he outsmarted himself, ‘The Hustler” (1961) as an avaricious agent, one of many crazed generals in ‘Dr Strangelove’ (1964), before taking the world by storm in ‘Patton’ (1970). He also did a noteworthy television series ‘East Side, West Side’ (1963-1964) as a social worker in the bowels of New York City. He had the reputation for professional intensity that sometimes put off other actors. Once he was in-character, he stayed there for the duration. Though not trained as a method actor, he out-methoded most of them.

That intensity shows in another role.

That intensity shows in another role.

The IMDB entry is sketchy with only first names for the characters, and not all of them. It has a rating of 7.0 which is respectable but not high enough.

I saw ‘They Might be Giants’ on the wide screen in Edmonton Alberta Canada when a callow graduate student and a night at the movies was a major financial commitment. It was memorable and I have checked many times in the following decades to see it again. No luck. Then a few weeks ago I happened to check again and lo, there it was on the Amazon site. I ordered it and when it arrived, I ripped it open and watched it, a rare treat that has withstood the test of time.

Krimi Fans, sub species Maigretistes.

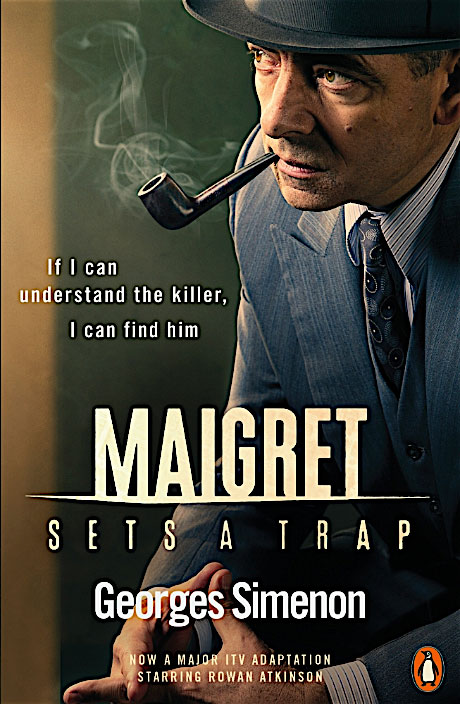

Put aside suppositions and watch Rowan Atkinson as Maigret.

My membership in the Maigret Fan Club began way back in high school French class, and has continued through irritated readings of Penguin translations which take many liberties with the original text, compounding the sin by boldly proclaiming that they are faithful when it is plain that they are not. I have read all the stories, including ‘Maigret’s Memoirs’ in which Jules Maigret recounts his association with one Georges Simenon.

While I enjoyed MIchael Gambon’s turn at Jules Maigret some years ago, and recently watched them again, they made many of the characters into cardboard to accentuate Gambon’s Maigret. Gambon was a perfect fit for Maigret physically. Rowan Atkinson is not the doppelgänger of Maigret but his performance is compelling for its simplicity, its inwardness, its intensity, its prism for the emotions of others, its humanity.

‘Maigret Sets a Trap’ is a gem. It is quiet and slow, qualities that are sure to bore some viewers, but for those with an attention span, it repays attention. The crimes are terrible, the press is irresponsible, the politicians are desperate, and through it all plods Jules Maigret. He has nothing to say to the representatives of the press who joyfully blacken his name. When assailed at a dinner party about the incompetence of the police, he says nothing. Indeed, this Maigret says even less than Simenon’s, and the silence is itself a message. When threatened with censure by his superior, Maigret persists in doing things his way. He says nothing, no theatrics, just more plod.

Margret chooses, as he knows he must, to tell the family of victim, and it is agonising. Almost nothing is said, but the weight of responsibility on Maigret is palpable.

The trap fails, and the minister has to have a scape goat. But the trap did produce a button, and from that button a mighty Niagara eventually flows. (A reference to an aside of Sherlock Holmes on the volumes that can be found in scraps of evidence.) It is ground pounding, endless interviews, triple cross-checking, meticulous examination that finally locates the culprit. No flash of semi-divine insight, no laboratory magic, no table pounding or shouting. Just more plod.

We all know Maigret will prevail, yet there is tension, mainly produced by the silences. Maigret’s techniques of interrogation consists largely of silence, patiently waiting to be told. The desire to tell someone, that is a theme in many of the Simenon’s Maigret novels, sometimes it is boasting, and at other times it is confession.

The team of Lucas, Maigret’s alter ego, muscle man Janvier, and the boyish La Pointe are established.

As Sean Connery IS James Bond, so Jean Gabin IS Jules Maigret with that weathered face, scarred by combat service with the Free French.

As Sean Connery IS James Bond, so Jean Gabin IS Jules Maigret with that weathered face, scarred by combat service with the Free French.

Georges Simenon, one of Belgium’s most successful exports.

Georges Simenon, one of Belgium’s most successful exports.

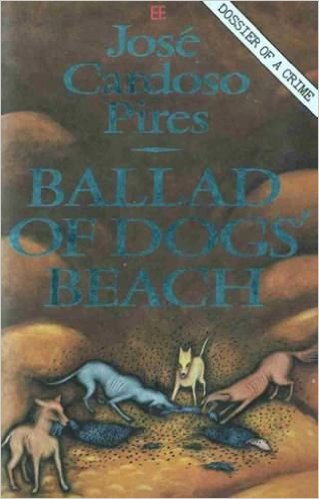

José Cardoso Pires, ‘Ballad of Dogs’ Beach’ (1982)

A Portuguese krimi set in the 1960s during the dictatorship of Prime Minister Antonio Salazar who ruled from 1928 to 1968 with both velvet glove and iron fist. A body washed up on a beach and the police arrive. The corpse is that of a man, slightly disfigured by the water but clearly murdered, who is identified as army Major Luis Dantas Castro, a soldier with a distinguished record in Portugal’s many African wars.

The homicide squad opens a dossier, but then it seems PIDE is involved. PIDE? Policia Internacional e de Defensa do Estado, the secret political police. Some months before Dantas had escaped from confinement for plotting the overthrow of the regime. Much of the novel is almost documentary as Inspector Elias Santana studies the dossier. Footnotes add to the verisimilitude.

The inspector is an introspective, methodical, and repressed fellow who speculates, even fantasises about might have happened. Was Dantas killed by government agents? By his own comrades in conspiracy? Or because of sexual jealousy? Elias tries to reconstruct Dantas’s last few weeks of life, working from scanty evidence. Elias uses his imagination to create the scenes at the conspirators’ hide-out that led up to the murder.

Sad to say that the novel is cryptic, hard to follow at times, and of most interest to those curious about Portugal of the time. And they were interesting times.

José Cardoso Pires

José Cardoso Pires

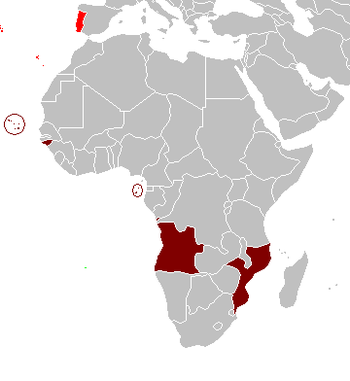

In the 1960s the Portuguese Army chaffed at the isolated and insular dictatorship, in part because it was under-equipped and under-funded for the ambitions of its officers and also in part because the regime neglected its restive colonies which the army had to secure. At the time the Portuguese Empire included Goa and two other smaller enclaves in India, East Timor, Macau, Angola, Mozambique, Sao Thomas, Cape Verde, the Azores, and Guinea Bisseau and…. The one that got away, Brazil.

Portuguese Africa

Portuguese Africa

Between 1960 and 1974 Portugal was engaged in three colonial wars in Africa in Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea Bissau.

While other European powers had been, often reluctantly, withdrawing from colonial empires, Portugal, neutral during World War II, had not. By 1974 it had 220,00 soldiers in combat in Africa. The financial, social, and political impacts in Portugal were extensive. The combined populations of Sydney and Melbourne come to about eight millions, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Imagine them together sustaining three wars in northern Asia without allies.

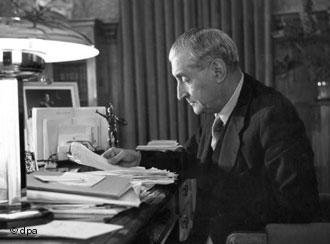

Salazar was an intellectual, an economist by education, who conceived of Portugal as a pluri-continental, multi-cultural nation. The colonies were provinces which were at a distance from Portugal, but represented in the parliament. Salazar wrote papers and gave speeches on these themes which taken together with Portugal’s undiluted Roman Catholicism, largely untouched by the Enlightenment, made it the New Jerusalem for the entire world. He termed it the Estado Novo, or the New State, a model for all others to follow. This backward, repressed, impoverished, and inward looking country, according to Salazar, was the only pure expression of the West! (Compare to Albania for its communist purity at the same time.) Like many intellectuals, he apparently mistook words for deeds, and was content to talk, not act.

Antonio Salazar

Antonio Salazar

During the two generations that he dominated Portugal, it was sealed off from the world. Border control was stricter than in Berlin before the Wall. The PIDE had a reputation like that of the Statsi though not the same kind of massive budget.

Travel was restricted and all travellers had their baggage searched. not for drugs, but for books that might be illicit. Karl Marx was at the top of that list but also on it were Thomas Paine, Jean Jacques Rousseau, and William Shakespeare.

A special literature evolved, cut down to Portuguese size. Huh? All the great works were translated and edited to remove the big ideas of autonomy, liberty, human rights, majority rule, women who were not barefoot and pregnant, judicial review, the rule of law, equality, these were all removed. For example, Marie Curie was excised from science texts. The Beatles’ music was banned. Foreign movies were cut for screening to remove ideas as well as sex.

Even Spain, ever a frenemy, was viewed as lax and kept at arm’s length.

Brazil was a problem. The regime wanted trade and cultural relations with it because it was and remains the largest Portuguese-speaking country but though it had its own dictatorship, it accepted Portuguese exiles who set up opposition groups there. Because Portugal allowed first the Allies and then NATO to use the Azores it was tolerated and left to its own devices during the Cold War. Perhaps Salazar even hoped that one day Brazil would return to the Portuguese embrace.

There were incidents including the high-jacking of the Portuguese cruise ship the Santa Maria in 1961 by some army officers in mufti. They captured the ship with the aim of going to Angola, amid much publicity to attract supporters, to set up a government in exile. They were soon apprehended as pirates, and instead went into exile in Brazil.

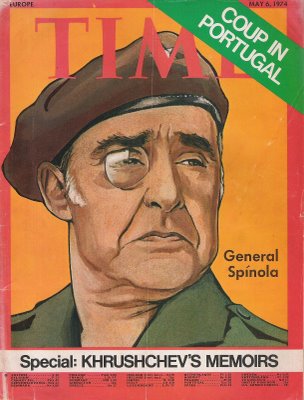

When the African colonies rebelled with some encouragement and very little support from the USSR, the overstretched Portuguese army lost. Betrayed by the regime, now presided over by Salazar’s heir Marcello Caetano, another economist, junior officers (captains, even lower in rank rather than the Greek colonels) effected a coup d’état, and into the breech stepped the flamboyant General Antonio de Spinola (1910-1996), who had had combat successes in Africa yet was known to oppose the wars. The coup was set in motion by a signal, namely a certain fado ballad in which a carnation was a token between two lovers was played on national radio at a specified time. Thus began the Carnation Revolution.

The regime, seemingly eternal the day before, fell in one stagger. The result morphed into democracy in Lisbon. Spinola wore a monocle, ergo flamboyant. There are a few parallels to De Gaulle’s return during the Algerian crisis in France, but with this difference, Spinola was committed to ending the wars and he did. It was said then and now, that only he could have done this. He had served among Portuguese volunteers in the Spanish legion with the Germans at Leningrad, and had led successful military operations in the Portuguese African colonies. His family was connected to Salazar. As a result, he had credibility and prestige with the old guard, but at the same time he was a hero to the captains and earlier he had made clear in writing his opposition to the wars at the expense of his own career.

‘The Murmuring Coast’ both the novel and the 2004 film comment on Portugal’s African war(s) in a restrained way. The film screens on SBS now and again.

True his word, General Spinola ended the colonial wars from one day to the next and negotiated settlements with the African colonies, made contact with China about the future of Macau, and left Timor. Thereafter as Portuguese democratic politics went left in the heady days, now largely forgotten, of Euro-Communism, Spinola went into exile himself to Brazil, where he plotted against the democratic regime with a small group of acolytes in a pathetic coda for a larger than life figure. He did return to Portugal and lived the rest of his days in quiet retirement.

There seems to be no biography of him in English.

‘Alexander Hamilton: A Life’ (2003) by Willard Randall

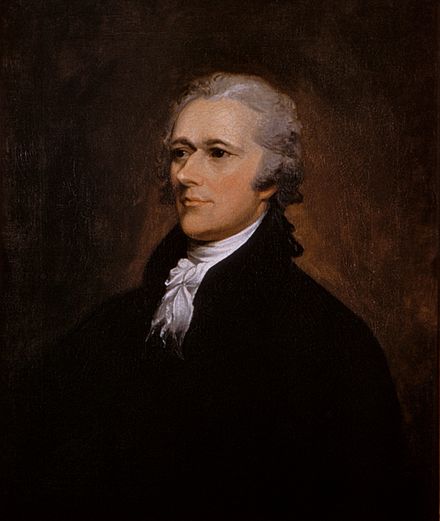

Alexander Hamilton (1755 –1804) was widely expected to succeed George Washington as leader of the Federalist party, which advocated a strong central government. That is until he was murdered by Vice-President Aaron Burr. Yet his face is there on the ten dollar bill. To find out why, read on.

Born out of wedlock on the Danish island of St Croix in the West Indies, he was legally a bastard. His mother, a French Huguenot, died when he was fifteen and left him an orphan. He attended a rabbinical school on the island because the Christian schools would not accept a bastard. He was both intelligent and quick to catch on, but his education was basic. He went to work at fourteen for the Cruger Brothers trading company in St Croix which had headquarters in New York City. In later life he was religious, but it is not at all clear he was ever baptised.

Now part of the US Virgin Islands.

Now part of the US Virgin Islands.

When the local proprietor, Cruger, became ill and returned to New York for treatment, he left his chief clerk, the boy Hamilton, in charge for a few weeks that unexpectedly turned into months. Hamilton had lied about his age to get work by adding two or three years. As Cruger’s absence stretched over the months, Hamilton ran the business, made decisions, signed orders, negotiated prices, initiated law suits to secure payment, signed correspondence, deposited monies, honoured contracts, and took several initiatives. When the owner returned he was very pleased with Hamilton’s stewardship.

This period of management was crucial to Hamilton’s subsequent career. St Croix was part of the triangle trade in slaves, rum (sugar), and New England goods. The man-child Hamilton ran slave auctions. He bought from and sold to New England merchants, who came to know his name from these transactions.

He also drew some conclusions, albeit slowly. First that slavery was abhorrent after his first-hand experiences, and he acted on that conviction often in later life. Moreover, he concluded that those American colonies with which he was trying to do business needed a cash currency of their own, and to get that they had to be united. He also acted on this point later. Without that the business was transacted by converting Spanish dollars, to Portuguese Josephes, to British pounds, to weights of gold or silver, and so on. None of these European currencies was readily available in the New World. Hence transactions were often paid with a mix of coins, metals, and bartered goods. Moreover, a mix of currencies and coins that worked for a Massachusetts contract, did not work for a New York one, and so on and on.

A hurricane flattened St Croix, bringing business to a standstill and in the doldrums Cruger decided to send his protégé Hamilton to the United States for an education. Smart as he was, Hamilton had no systematic education and had to start from scratch to prepare for the entrance examination to the College of New Jersey, before it became the country club of Princeton, until Woodrow Wilson made it into a university. His employer’s connections put him in the company of the social and economic elite just as New York City was becoming the chief city of the American colonies.

Arriving by ship in Boston, he found it an armed camp. The ten thousand citizens were sequestered by two thousand British army regulars. There had much restiveness among the locals because the British parliament was intervening ever more directly into each colony in the search for taxes to pay debts incurred in London. The crown dissolved reluctant local assemblies. Direct taxation was introduced. Protests were ignored. Delegations to the governor(s) were met with a wall of red coats. As Edmund Burke said, the British government’s actions drove the American colonists to rebel. All of this was much discussed by his travelling companions in the week-long stage coach ride to New York City.

Some of the division was religious with Anglicans siding with the crown, and Presbyterians with the colonists. To some Anglicans to dispute the prerogatives of the crown was blasphemous as well as treasonous.

Hamilton had a box seat to observe events because the members of the New York City elite he joined were in the firing line. It was their businesses being taxed, regulated, controlled in ways never before done.

While Hamilton performed well in the Princeton entrance oral examination, he was refused a place. No explanation survives. The author speculates that his bastard origins might have become known. When Hamilton next visited at Princeton, he came with cannons (during the Revolutionary War). He then turned to King’s College in New York, which was dominated by Anglican loyalists but…needs must. In a later evolution it became Columbia University to leave behind the English connection.

The pot continued to boil and the precocious Hamilton wrote anonymous pieces for newspapers on Enlightenment rights, though largely unschooled, he had read some of John Locke and had a good turn of phrase using natural and geographic images that communicated readily. But by day he sat dutifully in class and kept his opinions to himself. He did however join one of the militia companies created by the Sons of Liberty, which drilled around the local Liberty Pole. He was good at mathematics and learned trigonometry that made him an artillery officer in no time. Later he wrote the bulk of ‘The Federalist Papers’ which was once required reading in every college American history course.

He was not particularly good-looking nor did he speak well, or have a commanding presence according to contemporary descriptions and reports. A sloping forehead, a lantern jaw, a disproportion among his features, close-set eyes were described by his friends. Some of these were later masked by artistic technique in portraits.

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton

But he did have brains and a will to match which took the form of an enormous appetite for work.

First and foremost, he was Washington’s chief of staff during the last half of the Revolutionary War, and Hamilton did much to win it. He founded the Artillery Corps, and made the first plan of acquisition and use of cannons. He wrote the Infantry Drill Regulations, the training manual of the US Army, and he trained much of George Washington’s Continental Army with it in hand. He was twenty-three at the time. As a field commander he promoted men from the ranks to officers, and this outraged many of his social superiors, but he persisted, and prevailed. He outraged still others by advocating, proposing, and planning to emancipate slaves to help repel the British in the south. On this one he did not prevail but antagonised many. Washington supported both these latter initiatives, but even his prestige was inadequate to the second proposal.

One of the many ironies is that South Carolina refused to consider freeing and arming slaves, and Charleston was then duly invested by the British who promptly freed its slaves and enlisted them in the British navy, about 2000 in all. By the way, Dr. Copeland, the indomitable black physician in Carson McCullers’s ‘The Heart is a Lonely Hunter’ (1940) named one of his children after Alexander Hamilton.

Hamilton was slandered by the Tea Party of the day for his bastard birth, his lack of parents, his Jewish education, and his foreign birth. An orphan, a bastard, a semi-jew, and foreigner. Imagine what Trump Donald would make of that. ‘What a loser!’ For several years while attached to General George Washington’s staff, Hamilton was responsible for all prisoners of war. He negotiated with the British many times to exchange prisoners, to improve living conditions for Americans imprisoned, to seek compassionate release for individuals, to create a schedule of exchanges, to procure medical treatment and food for both American held by the British and for British held by Americans. For his trouble, rivals labeled him a British spy. With the same scruple, when the French entered the war as an ally, the native French-speaker Hamilton became Washington’s liaison with the French. As he spoke French with them, rivals labeled him a traitor for revealing secrets to these foreigners. It is easy to image Fox News mangling all this into one of its outraged broadcasts.

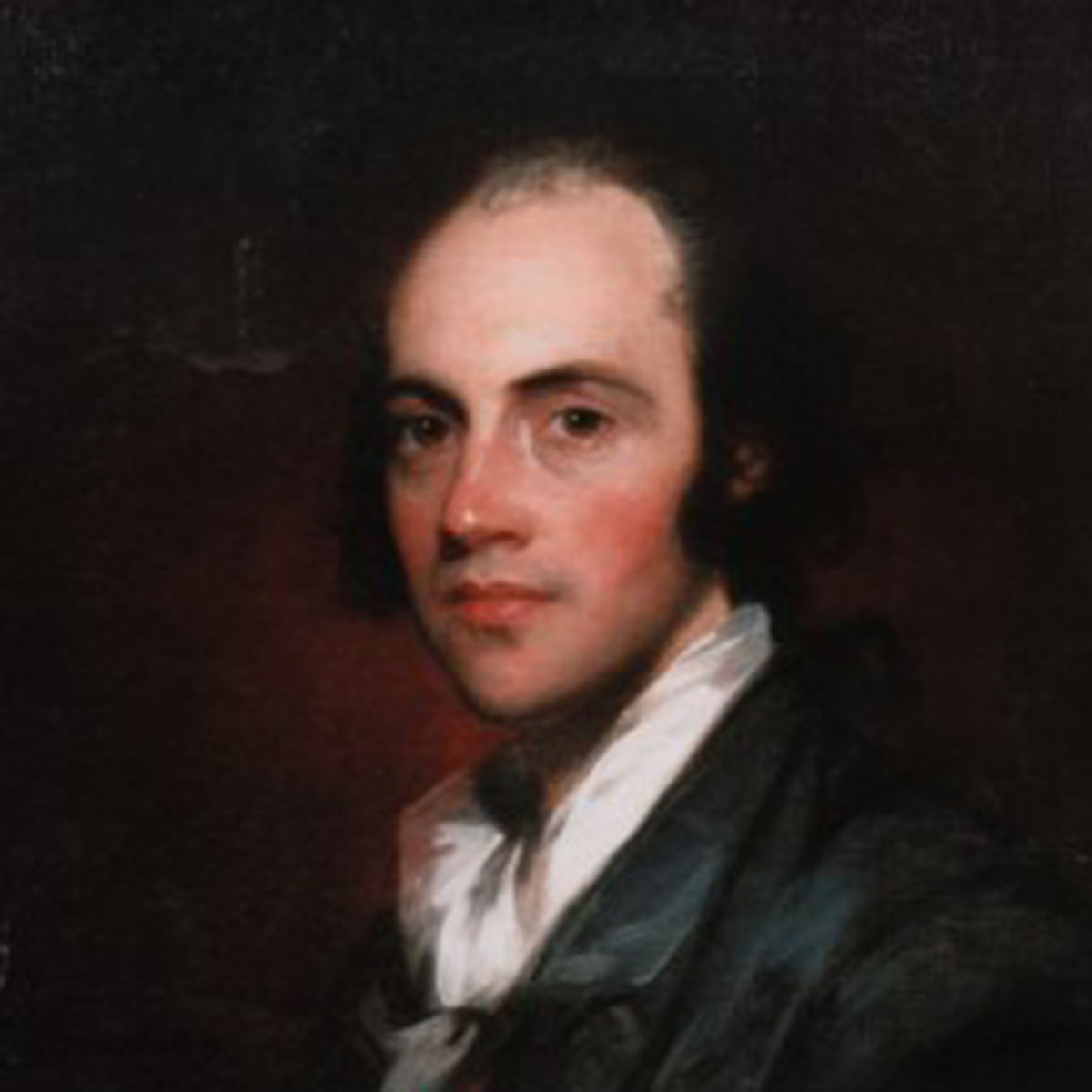

Burr and Hamilton crossed paths many times, first, in the Continental Army, where Burr served a general who hated George Washington and all who served with him, a hate the good subordinate Burr internalised. They were also thrown together after the war in legal studies and in their careers in law. Though neither was important enough to the other to figure in any of the surviving letters from that period. Later when Hamilton bought a house in New York City, Burr was the conveyancing lawyer for the vendor.

Perhaps because of his background, Hamilton tried to be more of a gentleman than anyone a gentleman by birth. Ergo he was ever alert to insults and slanders, and challenged to a duel more than one person he perceived to have slighted him. The first few of these challegenees declined the honour. Washington himself rebuked him for doing this, supposing there were more pressing matters at hand.

While he was de facto chief of staff for General Washington, his official capacity was an aide-de-camp, a messenger, and the highest rank he achieved was lieutenant-colonel. As an aide-de-camp he could go no higher. Ambitious as he was, and sure that the war would end in a British defeat, he wanted to rise higher, and left Washington’s service to seek a field command in order to do so. There was a rupture of sorts, though each regretted it and said so, but Hamilton got a command with the New York militia and played a decisive role in the final attacks at Yorktown, leaving the army as a full colonel and a reputation for success on the field of battle. His attack at Yorktown was coordinated with the French army there, and proved to be the end.

He married into a wealthy Dutch family but strove always to live off his own meagre income, as a soldier, public servant, lawyer, and author. That was not easy and his wife often took the children back to the paternal estate on the Hudson River.

Washington made him Secretary of the Treasury and he worked like a demon to make the USA a viable economy, through a sinking fund, a national debt, debt consolidation, the mint, the dollar, the reserve bank, tariffs, customs, and more. He won compliance from the states by assuming their debts from the Revolutionary War. Somehow he found time to ease Vermont’s secession from New Hampshire and entrance into the Union as the fourteenth state. He worked twenty hours a day for many stretches, far more than any of the clerks employed in the Treasury who arrived at work each day to find trays full of directives, orders, draft letters Hamilton had written overnight. At one time he employed twenty-seven clerks exclusively working for him.

Though a native French speaker, and an admirer of French writers and fashion, he foresaw ‘the special relationship’ between the United States and Great Britain and worked at repairing relations with England, first through commerce and later through some unofficial diplomacy, which aroused the animosity of the French lobby in the person of Thomas Jefferson.

During the Quasi-War with France (1798-1800), President Adams commissioned Washington as Commander in Chief who appointed Hamilton a major-general. Since that war was mostly maritime, Hamilton bent himself to enhancing the US Navy and together with President Adams he can be credited one of its chief founders.

Aaron Burr, one time Vice President who murdered Hamilton and was later tried for treason at the order of Thomas Jefferson.

Aaron Burr, one time Vice President who murdered Hamilton and was later tried for treason at the order of Thomas Jefferson.

Hamilton was never much of a husband to Betsy, the shy, retiring, insecure, hesitant, ill wife who bore him five children; he preferred the company of her vivacious, extroverted, well-read, worldly sister Angelica, but there is no reason to believe it was sexual. But he was putty in the hands of a pretty face. When Benedict Arnold bolted, Hamilton believed the lies told by Mrs Arnold, and gave her money, which she promptly used to bolt and join Arnold. Later another woman seduced him and Hamilton crept around to her backdoor several times a week for eighteen months. Her husband then set about blackmailing Hamilton at the very time when John Adams was promoting Hamilton as a presidential candidate. Think Gary ‘The Zipper’ Hart.

The rumour mill worked overtime and finally Hamilton told all in a pamphlet to save his reputation as a public servant and the credit of the Treasury department, at the expense of his personal reputation. Hamilton then resigned. Despite more than twenty inquiries, investigations, trials no peculation was ever discovered. His wife found out of this infidelity by reading about in the newspapers.

But he could not leave public life, and campaigned in the gubernatorial election in New York state against Aaron Burr. Burr claimed Hamilton had slandered him at a private dinner party and challenged him to a duel, and killed him before he reached fifty.

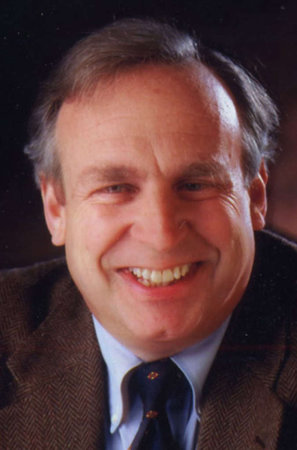

I read Randall’s one-volume biography of George Washington some years ago and liked it.

Willard Randall

Willard Randall

There is no summing up at the end of the book, so here is mine. Hamilton was an economist avant le mot, one of the very few who realised the importance of establishing the financial viability of the new country even during the Revolutionary War. He had a great capacity for work in the best of the Puritan Ethics. Though many tried to blacken his name, including some heavy hitters like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, his personal probity was absolute. Hamilton was clear-headed and rational in argument, and in anger grew cold and slow, but he never seems to change his mind or accept compromise, though he had enough sense at times to leave the room rather than erupt in anger.

He rose to the occasion time after time and in different ways, first in arriving in the north America, then as a soldier, and then as an economist. He was inventive and no insurmountable task discouraged him. He also despised mobocracy or democracy. The state governments were democracies and to his mind they were irresponsible, corrupt, and incompetent and they would always remain.

But he also he also was putty in the hands of several women, at the expense of his wife, and one of those dalliances, which certainly was sexual, was his downfall.

In public life he made enemies easily, and often deliberately. He would name those who opposed his arguments as dunderheads. The wonder is that he was not killed in a duel earlier. Some of this seems to have been his intellectual arrogance. John Jay was his tutor in college, lent him money in later life, worked with him on the ‘Federalist Papers,’ but once when Jay differed from Hamilton he assassinated his character in print without hesitation.

This book is marred by non sequiturs that increase toward the end, and the story of his last years is truncated compared to the nearly day-by-day account of earlier years. That unevenness may reflect the paucity of sources, the fatigue of the writer, or the demands of the publisher. Whatever the reason, it is obvious.

By non sequiturs I mean passages like this: ‘Hamilton’s proposal was widely opposed. It passed easily.’ Huh? I had several of these ‘Huh?’ moments. There other inconsistencies. Early on Hamilton is said to be not attractive, and later he is said to be so. The goal posts seemed to move.

At some point it is said Hamilton advocated rights for women, but I had not noticed anything on that subject to that page, nor indeed after it.

I also found distasteful the opening of the book with the duel and his death. It makes almost no sense put first without the context of his life, if not his times. But it is lovingly detailed, the stroke of the oars, the colour of the coat, the shine on the pistols. I suppose this was the demanded by the publisher.

There are also some typos. This from Harper Collins.

‘The Murder of Mary Russell’ (2016) by Laurie King

Another entry is a brilliantly conceived and executed series featuring an ageing Sherlock Holmes and his bride, many years his junior, but nonetheless his equal. She had to be to displace ‘The Woman’ from Holmes’s mind. Baker Street Irregulars know who the ‘The Woman’ is. I am not sure that Mary Russell has yet learned about her in this series.

There is a lot to like about these krimis. There is energy, movement, period detail, and most of all the characterisations of Russell and Holmes but also others whose path they cross from the cantankerous Mycroft, to ingenious Billy Mudd, to the redoubtable Mrs. Hudson who has much up-stage time in this entry.

Much of this title concerns Mrs. Hudson’s past live(s) and even that of her parents (we are spared the grandparents) told in a novella within this novel on the order of a Charles Dickens novel of the dark, noisome, and sinister Victorian London, with a long side trip to sunny Sydney. All of this is well done but of no interest to this reader, and probably not to many others, who like this reader, follow the series for Holmes and Russell. I thumbed those pages quickly on the Kindle and there were a lot of them, a lot. Holmes does eventually make an appearance there, too little and too later for this reader.

However the action returns to Russell and Holmes and crackles when it does. I found Russell’s message to Holmes unfathomable. Nor did I follow the reasoning about the flight. But who cares, that is like quibbling about the colours on a racing bicycle as the rider drives it up L’Alpe d’Huez.

Laurie King

Laurie King

Mrs. Hudson has had her due in an another series, e.g., Martin Davies ‘Mrs Hudson and Spirits’ Curse’ (2005) and many others.

The conceit in this series is that she solves most of Holmes’s cases with her below stairs contacts but lets Holmes upstairs think he has done it on his own.

Eat the stupid?

Eat the rich!

How amusing. I saw this exhortation in a feed on Facebook. Everything old is new again.

When people say I have no sense of humour, they are right. I never had a sense of humour about the racist and sexist jokes either. When the racists and sexists tried the fig leaf of humour as a cover I did not relent. That was when I learned I had no sense of humour.

Adolf Hitler had the same idea about the rich. He had every last member of the Rothschild family that could be found, one branch of which owned a bank of that name, hunted down, imprisoned, humiliated, tortured, and murdered. They were rich. Very.

However, being a vegetarian, he did not eat them.

Some of the Rothschilds were incredibly rich and they all were Jewish after all. Hard to say which was the greater crime. They got rich, in part, because they took risks other bankers were unwilling to take, e.g., like lending money for the building of the Suez Canal. But more generally to lend money to other Jews because Christian-owned banks would not.

For what it is worth, the surviving Rothschilds stem from other branches of the family, some living in England who survived in that liberal-democratic society so despised by the people who exhort others as above.

No doubt, I will shortly be unfriended.

By the way, the Rothschilds remain a whipping boy for all manner of nutters on the internet. Adolf’s spawn.

‘Wolves and Angels’ (2012) by Seppo Jokinen

A krimi from the industrial city of Tampere (population 364,000) in the forests of Finland.

Winter in Tampere

Winter in Tampere

Detective Saraki Koskinen probes and pries, in between outbursts of temper. He is wound up as tight as the clichéd spring. Divorced, he combines workaholism with fitness fanaticism to fill in the hours. He jogs, well, races, at midnight or later and rides a bicycle everywhere, as fast as he can. Consequently, he sweats a lot and needs showers and clothes to change into, and these he carries. He is organised, but some things always go wrong and he is caught in embarrassing situations, which occasion outbursts of temper as compensation.

There is a murder victim, a paraplegic. Who would want to murder a cripple? Perhaps anyone who knew this bad tempered man, whose affliction just made him more aggressive and violent, having perfected ways to use his mechanised wheelchair as a battering ram, especially against people who underestimated him in that chair. In the assisted living home everyone has a bad word to say about him: Loud, noisy, drunk, violent, rude, inconsiderate at all hours, starting to sound like a teenager.

Then there is an a second victim, an elderly man who lives near the home but not in it, and who was near death from cancer. Then a third, another resident of the assisted living home, a woman whose paralysis was so great she could barely speak.

Are the three murders related? Are the three victims connected somehow? Are these perverted mercy killings? What does the perpetrator gain from the first, the second, and the third death? Is the second murder part of the sequence or a coincidence?

The novel is a police procedural and the squad interviews and re-interviews all the residents at the home, the visitors, the staff, the suppliers, and neighbours without getting traction. In the course of this members of Koskinen’s squad argue with each other about overtime, office supplies, and the assignment of duties. It is by no means a happy crew. Seldom can anyone say more than two words without interruption, or someone stomping out of the room in anger. Koskinen is not the only one wound up tight. As the leader he seems unable to calm them down.

Koskinen has yet another new intern as a temporary secretary-receptionist who cannot stifle the urge to rearrange his papers neatly. Her well-meaning but misjudged intrusions lead him to one burst of temper after another, which seem to wash over and off her. Just as well because there are more to come.

In addition, his team members bully one junior detective, and though Koskinen is dimly aware of it, he cannot figure out what to do about it, and being a man he cannot ask for advice. Bullying in this case seems to be an outlet for the frustration of the others vented on the weakest member of the group. The frustrations are about the case, about the malaise of the police service, about personal irritations, about anything and everything.

When some uniformed patrol officers forget to report the discovery of an abandoned wheel-chair, there follows another outburst of the well-known Koskinen temper. That the patrol officers forgot because they were involved in a particularly gruesome traffic death only slightly reduces his outrage.

After each outburst, he realises he is not in control of himself, wishes he had not done it, and cannot apologize. See, life-like.

Meanwhile, there is much about Finnish manners and morēs that I found interesting. But even more about the paraplegics and quadriplegics at the assisted living home, their ways of coping with life after paralysis, of finding satisfaction (food, drink, drugs, sex), and the relationships among them.

In the hope of a speedy resolution before the media hysteria leads to an intervention from Helsinki, the police chief points to an intruder as the likely culprit, but Koskinen, in the best tradition of the genre, is sure the villain is in the home or closely associated with it. Indeed.

Though that conviction is undermined by a close study of who had access and who has keys to the building. There is an official list for each, both short, and a real list, both much longer. On the real list are taxi drivers, prostitutes, delivery drivers, close relatives, medical specialists who hand the keys to locums, and more.

As is compulsory in the contemporary genre, there is much about budget cuts in the police but also in the assisted living home. There is no staff member in the home overnight but rather an elaborate electronic security system to monitor the residents and the building. The latest in IT. But in a crisis it signals a security agent who has a twenty-minute drive to get there, if the weather is good, more if there is rain, wind, or snow, as there is nine months a year. According this agent arrives too late each time.

Meanwhile, when not pedalling or racing, Koskinen sees television interviews with the national Police Minister talking about further budget cuts in policing, and outsourcing more and more police duties to contractors with such IT setups. This lifts his morale, not.

As always I find keeping track of such unfamiliar names a challenge, but the author very clearly distinguishes and delineates the characters and that helps a lot.

Seppo Jokinen

Seppo Jokinen

There are many other titles in this series featuring Saraki Koskinen in Finnish, but this seems to be the only one translated into English as yet. I do hope more are on the way.