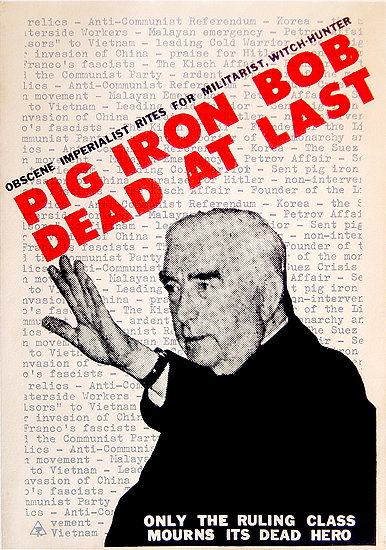

Every Australian of a certain age has heard this term, ‘Pig-Iron Bob,’ and knows what it means. I did, too, until I read Geoffrey Blainey’s ‘The Steel Master (1973),’ reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

[No comment.]

[No comment.]

As with so much common coin, the Vox Populi is exactly wrong.

First to the common interpretation. While Robert Menzies was Prime Minister, Australia sold pig-iron to Japan in the later 1930s which pig iron the Japanese turned into weapons to attack Australia. That is the claim, and there are many chest-thumping assertions about it on trade union web sites.

It is another myth, like the Brisbane Line. Never existed but became reality by repetition.

Let’s start with the basics. Pig iron cannot be shaped into weapons-grade steel. It is a by-product of steel production not the basis of it. Cause-and-effect can be tricky like that.

BHP did indeed sell that pig iron to Japan, that is true. It did so to prepare for war with Japan. Huh?

Essington Lewis, that remarkable man, who was CEO of BHP, foresaw a Pacific conflict with Japan as early as 1936, while so many of the Lefter-than-Thou persuasion were still toe-ing the Moscow line of friendship with the Axis powers. Lewis bore this message to all and sundry on his return to the wide brown land, but no one wanted to hear it for fear of provoking the Japanese. Softly, softly was the bipartisan foreign policy at the time.

Disappointed with the political response, on his own initiative he began converting BHP steel works to weapons production. While the board of directors chaffed at this unprofitable exercise, the chairman of the board backed Essington Lewis, and conversion went ahead full-steam, that being the only way Lewis ever did anything.

Lewis used the money from the pig iron sales to Japan to pay for this re-tooling of BHP factories to produced airplanes, ammunition, rifles, the Owen gun, Beaufighers, anti-tank guns, and ships.

In this way, the truth is that Japan paid for Australia to arm itself against its threat.

That phrase, like some other colossal lies in Australian politics, traces back to that tireless motormouth Red Eddie Ward. His admirers, a few of whom I have met, might also pause to consider that Ward also violently (but then he did everything that way) opposed home ownership, especially for the working class because it would sap their revolutionary fervour and delay the advent of Soviet Socialist Australia.

Fred Ward, Donald Trump is using his playbook.

Fred Ward, Donald Trump is using his playbook.

Pedant’s note. Grammar Girl advises that when a noun phrase is used as an adjective, it is best to put in a hyphen. Pig iron, the noun, becomes pig-iron the adjective. She is not alone. The redoubtable ‘New Yorker’ does the same. We village hicks but follow our leaders on this point.

Author: Michael W Jackson

‘Kill me Tender’ (2000) by Daniel Klein

When the teenage presidents of Elvis Presley fan clubs start dying, the King notices, and the more he looks into these deaths, the darker they become. Looking is one thing, acting is another, and for that he mobilises his posse and makes an alliance with an unlicensed doctor, an African princess (well, that is how Elvis sees her), and himself in the person of an Elvis impersonator, and also the five-year old brother of one of the victims.

What a treat!

This Elvis is polite, considerate, compassionate, colour-blind, and tenacious. He has to be because he comes across some very rough customers in this tale. While he is used to being demonised for the evils of rock-and-roll, in this case it is literal!

His music is a bridge that spans some of the racial and social divides laid bare in his inquiries. Though he finds more in common with the poor blacks he meets than with the uptight whites. They both have Bibles to hand, but in the former case it is a comfort, while in the latter it is weapon.

When Elvis sings a hymn, well, who cannot listen, who is not transported, who does not believe the sincerity of his tears? Many, many, do believe, but not all starting with the very angry father of one of dead teens, who blames Elvis twice over, once for being white, and second for that satanic rock-and-roll. The first victim that comes to Elvis’s notice is black.

The upright, uptight whites are even more difficult to fathom behind a facade of Calvinist politeness. While they accept their daughter’s death as God’s will, they do not accept Elvis intruding into the matter. But he cannot stop himself. These children had somehow connected to him and now they were dying. Was it because of him?

As for the local law, as much as they suck up to the King, there is no interest in stirring. Well, except for one sheriff who sees big headlines in arresting Elvis for these very crimes. The plot thickens.

Into heady brew comes a criminal psychologist. Elvis has thumbed through her book without much comprehension but he then telephoned her. That conversation in itself is worth reading the book. ‘Hello, this is Elvis Presley….’ Then there is Elvis’s huge, tattooed, menacing cell mate when the aforementioned sheriff arrests him who styles himself ‘The One.’ He seems to have more insights than even the glamorous New York psychologist who arrives (book contract in her brief case, suspects Elvis) to lend the King a hand.

When the going got tough, Elvis’s posse was more trouble than help, and he finds strangers more help than those on the payroll, including some of the jailbirds.

Elvis was a class act and this book vindicates that in spades.

The book offers a very sobering and painful account of the life of a celebrity like the King. He is a prisoner of his frame. He cannot walk down the street, drive his car to a park, visit a cemetery, book an airplane ticket in his name, or go to church. If he does, he is mobbed by fans and the media. HIs every move in public is splashed across the headlines and talking heads start yakking.

Daniel Klein, author a number of other books and novels.

Daniel Klein, author a number of other books and novels.

Warning! Musings follow.

This Elvis reading got me thinking about the impersonators. Why Elvis? Why Elvis and not … [fill in the blank]. Why are there hundreds, thousands of Elvis impersonators from Malta, to Tallinn, to Montgomery? Why are they still at it now, thirty-five years after his death?

Of course there are impressionists who imitate Madonna or Brad Pitt on a TV skit. But none of those idols have the army of global impersonators that Elvis had and has. And that is the point, anyone can be imitated and many are. But why is it only the King with such an army of autogenetic impersonators? (Well, maybe not Brad Pitt since he has no personality to mimic.)

A few years ago we saw an exhibit of photographs from the early years of Elvis. The overall impression was a modest boy struggling with the demands the world was just beginning to make on him. Particularly arresting was a photograph of him walking home from the train station after his first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show, a young man in blue jeans and shirt sleeves, like every other one, waving goodbye to those still on the train.

On my pilgrimage to Graceland, three things impressed me.

One was the music. It was everywhere.

The second was a video that included Elvis backstage in Los Vegas toward the end, saying ‘I am so tired’ in a voice that left no doubt that he was very tired, but the show had to go on, and off he went, in that grotesque white jump suit.

The last thing was the line of people, men and women in the shop, European and Asian, who queued up to have a photograph taken with a holograph of Elvis. Ghoulish. The King still has no rest from the rapacious appetite of the fans.

Illegal immigrants, indeed.

Here is some food for thought, were that possible for the Donald Trumps (and Peter Duttons) of this world.

Who is the most famous American illegal immigrant?

There are many candidates, but have a look in the wallet, bleaders in the U.S.A. Got a ten spot? Look at Alexander Hamilton. He is one of the finalists.

First, why is he on the ten, and then how did he get there.

He is on the ten because he created the United States currency. He devised the reserve bank system, coinage, paper money and a lot more. A founder indeed. (He was also an artillery officer in the Revolutionary War, more military service that Trump has seen.)

Until he was murdered, it was widely supposed Hamilton would succeed George Washington as leader of the Federalist Party. It was Hamilton who first bruited the Washington Monument.

Hamilton was also an undocumented, illegal immigrant born out of wedlock to a French mother on a Danish island in the Caribbean Sea who entered America at age eighteen. What a trifecta. Moreover his maternal language was French. He learned English as a teenager at a Jewish school and from the Dutch businessman for whom he worked.

What would Trump or his local imitator Dutton make of that?

A voodoo frog on a bicycle and a bastard to boot. Literal in the case of Hamilton and figurative in the other cases.

The Foxy rapprochement – beat me by a day

The closer Donald Trump gets to the Republican nomination the more the media, other Republicans, and some Democrats will discover his virtues. It is always the same, every four years the cycle is repeated as though for the first time.

Earlier in the campaign qualities deprecated and ridiculed in a candidate, will come to be accepted and then celebrated as positive.

For example, inattention to facts will transform to strategic thinking, untrammelled by petty details.

For example, flippant and destructive remarks, will be transformed into suggestions, and trial balloons.

For example, hostility to Hispanics, refugees, Muslims, women, left handers, homosexuals, will become — thanks to the alchemy of opportunism — unifying remarks.

For example, vague and diffuse threats to other nations will become, presto, disguised diplomacy.

The media always leads the way in this prostitution. When it seems a candidate is going to win, the realisation follows that an accommodation will have to be made with the candidate to keep manufacturing the news.

Even a big target like Trump will get the benefit of this self-censorship. Indeed, the more he threatens the media, the sooner some of its representatives will fall into line in the hope of securing favours before others comply. When it comes to self-serving opportunism, no one can beat Murdoch’s organs.

Soon there will be a rapprochement between Foxy News and The Donald. ‘You read it here first!’

Other Republicans will accept their own candidate, no matter what. All the posturing and playing hard to get will evaporate when success looms. The office seekers ever so subtlety seek office with more finesse than Chris Christie.

Then there will be Democrats who see Trump’s pull in their electorate, and have no wish to rile voters. These are the ‘If I keep quiet maybe their will not notice my party label is Democrat’ leaders. Some of them will couch their campaign publicity to omit the very word ‘Democrat.’ such leaders as they are.

Jimmie Carter went from ‘Jimmie Who?’ to a sage in this kind of transformation. Ronald Reagan’s habit of falling asleep in meetings, became a cool detachment. John McCain’s long past use-by-date became maturity. Mitt Romney’s narrow sectarianism became a virtue.

‘The Readers of Broken Wheel recommend’ (2016) by Katarina Bivald.

Chick Lit and I want more of it!

A delightful account of the culture clash between a single Swedish tourist who comes to Broken Wheel, Iowa, population 640 and declining. Sara is her name, and though she is classroom fluent in English the Iowa accents and idioms do not readily translate.

The good citizens of Broken Wheel are delighted to find a tourist in their dwindling midst. Sara left Sweden because there was nothing there for her, and she is pleased to be warmly welcomed.

Sara, however is nonplused, because her pen-pal and prospective host for the stay in Broken Wheel, Amy, is nowhere to be seen. She and Amy have been corresponding about books and life for a long time. The absent Amy has left instructions that Sara should stay in her house and make use of her books. She does.

Caroline runs the town by the force of personality. Formal positions mean nothing, and in the end that pays off, but not before this pillar of rectitude learns herself of sin first hand. Wow!

Jenn chronicles it all in her newsletter, blog, and private diary. Grace observes with disdain, a shot gun at the ready. The Grace women are always armed.

George stays off the drink one day after another, that is, until his long lost daughter returns, and then leaves again. The second loss is too much for George.

Andy and Chris pull the beer at the tavern, and the six hundred residents accept this gay couple without a word.

Cornfields play a part, too, because after all it is Iowa; there are a lot of cornfields, but none as scary as the one in the first episode of ‘Star Trek: Enterprise.’

Spot the Klingon.

Spot the Klingon.

Then there is handsome Tom who cannot help noticing the new face in Broken Wheel. He is too handsome for her, and she is too smart for him, but, well, in books anything can happen, right Mr Darcy?

Then Gavin the regional representative of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service appears. Gavin hated his old job in the USCIS because he had to arrest and deport hard working, god-fearing, polite, resigned, clean, and illegal Mexicans who never complained about how badly they were treated.

His remit is now Europeans, and Sweden is in Europe, right? Europeans, these he is ready and willing to arrest and deport for the slightest infraction of visa rules. If only…

Gavin descends on Broken Wheel with the full might of Federal government at his disposal, and finds that he is overmatched against Caroline.

Katarina Bivald

Katarina Bivald

To give the devil its due, I noticed this comment on Good Reads

‘This book was absolute rubbish. 394 pages of stupid observations written in a clumsy and somewhat childish language combined with unbelievable characters.’

A salutary reminder of why I do not bother with Good Reads.

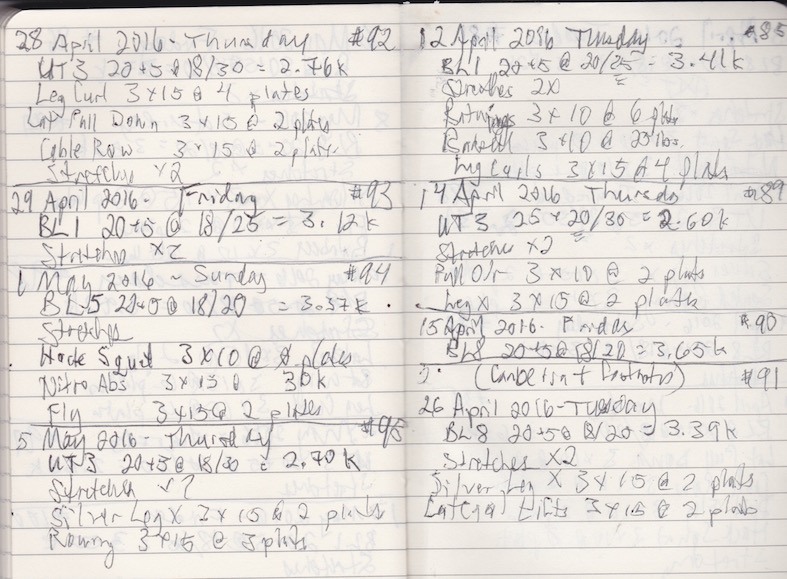

I did it! (Again.)

I have made one hundred visits to the Newtown Gym on the current annual membership, which continues to late September. Three or so days a week after walking the dog around the park I head for the gym, while Kate takes the mutt home.

I cannot vouch for either the 4 a.m. start or the midnight finish.

I cannot vouch for either the 4 a.m. start or the midnight finish.

A visit to the gym consists of twenty-five minutes on one of the stationary bicycles or the upper torso whirly-gig. There follow stretches of the calf and thigh. Then comes a test of some of the metals to see if they are still heavy. The weights will includes both leg and upper body.

When pressed for time I omit some, or all of the weights.

The gym routine involves a uniform of sweat pants and shirt with a red jacket, pockets stuffed with reading matter, water bottle, sun glasses for the walk to and from, cleaning cloth for the glasses, earphones, and a neck pouch for the iPhone and notebook. That is in addition to the house keys and wallet in the sweat pants pockets, along with the magic fob to enter the gym. Locked and loaded.

I read on the bikes and listen to podcasts on the upper torso machines, hence the earphones. If possible I use a device near a window to watch the world go by on King or Wilson Streets. The first choice is listening is ‘In Our Time’ with Lord Bragg from BBC4, followed by ‘The Writer’s Almanac’ with Garrison Keillor, and ‘Grammar Girl’ with Mignon Fogarty. Choices two and three come into play when his Lordship goes on vacation.

I keep notes on what I do at the gym, so as to vary the exercises from one visit to another, in the notebook. It is partly encoded, since I am the only reader.

Usually the routine is finished about 9 am. At home a star goes on the calendar date of each gym visit, as per daughter Julie’s instructions.

Here I am après le gym on the way to Best and Brightest last week.

‘Brazzaville Beach’ (1990) by William Boyd

A very unusual locale and set-up for a krimi. Bravo!

The action centers on a research station in the forests along the Congo River where a multinational group of scientists observe chimpanzees sometime in the 1960s. The narrator is a recently-minted PhD who muses on what led her to this place when she is not watching the monkeys. (I do so detest backstories because they are distracting.)

The book offers intriguing soupçons about the primatological research into the social customs, practices, and habits of a clan of chimpanzees, along with a study of their diet, and movements, including bowels.

In the distance, on the far side of a mountain range there is a four-way civil (tribal) war going on, and that spectre cannot be ignored, since it might influence the funding agencies to withdraw support. Of course, there are twists and turns among the scientist, though our protagonist is so junior, she seldom sees the professional rivalries firsthand. That is, she is out in the field observing, while back in the base camp the more senior members of the party wrangle over precedence. What she sees there in the field is remarkable and in time upsets the established order.

Spoiler alert.

The book recounts three intersecting conflicts: there is war among the chimpanzees, there is conflict among the scientists over the data and its interpretation, and the tribal war mentioned above. In time, the three come together. It is all very ambitious. The first two provided more than enough material, and this reader found the intrusion of the third inevitable and unnecessary.

The most interesting aspect is the primatology. The manners and morēs of the chimpanzees in the wild, the relations among them, including the conflict that is a war in all but name. But also of interest is the relationships of the primatology observers with the chimpanzees. The scientists personify the chimpanzees with nicknames, though technically they have specimen numbers, these latter are only used in the final write-ups. Nor is there any doubt that the chimpanzees recognise and distinguish the observers from themselves and that they know one observer from another, and there is one harrowing moment when that recognition is crucial.

Years ago as a prospective text for the Power course, I read Frans de Waal’s ‘Chimpanzee Politics’ (1985), a study of chimpanzees in the Arnham Zoo in the Netherlands, a book that is written with panache and insight, along with a few gratuitous reference to Machiavelli that I logged in my collection of inanities about him. While de Waal’s book has much technical detail about quasi-experimental tests done in captivity, it is easy enough for a general reader, and leaves one in no doubt of the intelligence and capacity to learn of chimpanzees.

Our heroine survives it all but some others (including some of the chimpanzees) do not. She finds that among the tribal warriors are some decent folks, that the mercenaries attracted to the conflict are a varied lot, that some of the scientists on the project are unscrupulous and mercenary themselves (really?), that the chimpanzees are capable of moral acts, that her husband’s suicide which more or less drove her to Africa remains a mystery, and that…. the most important lesson, life goes on even in Brazzaville Beach.

William Boyd

William Boyd

The writing is assured; the touch is light; the themes are serious as they slowly emerge. The context is richly detailed. Altogether a good book. William Boyd has others and I might read another one day but I will not make it a priority, because I thought this one had too many themes and circumstances competing for my thin attention. Once again, I seem to be in a minority because the back cover is plastered with testimonials from the highest sources like the ’New York Times.’

The title caught my eye because Brazzaville in the Republic of the Congo was where Charles De Gaulle made his second radio broadcast, this one to the French colonies. There was a large transmitter in Brazzaville, built in the 1930s to reach the African colonies and even some air and naval traffic. De Gaulle traveled there in 1940 to win supporters, and met with some success.

‘The Spinoza Problem: a Novel’ ( 2012) by Irvin Yalom

The setting in 17th Century Amsterdam shows assiduous research and the differentiation of characters is good, as far as I can tell. On that qualification there will be more later.

Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) repays effort. The first is with his name. He was born Benedito de Espinosa of Portuguese parents who had moved overnight to Amsterdam to avoid the convert-or-die (later) Iberian Inquisition. (Why does Ted Cruz come to mind?) The parenthetical reference ‘later’ applies because even Jews who willingly converted to Catholicism were subjected to subsequent persecution. In Holland he was sometimes styled Benedict. In all those permutations his first name means ‘Blessed.’

That qualification ‘as far I can tell’ means I stopped reading the book very early. I violate my rule of the positive in this case because I wanted to express my admiration for Spinoza the thinker. In addition his reputation as a man has come down the ages as a simple, unpretentious person, whose life was a model of rectitude, in contrast to the wastrel Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the gloom-and-doom merchant Thomas Hobbes, the obnoxious self-promoter John Locke, or the nutter John Stuart Mill.

Spinoza’s two tracts, the ‘Politics’ and the ‘Ethics’ are fine books, though arid. He much admired the method of geometric reasoning. Yet somehow he is not on the starting team in the Tour of Political Theory, so I only ever managed to slip the ‘Politics’ onto the syllabus once many years ago. Ditto his fellow Dutchman Hugo de Grotius.

‘The Spinoza Problem: a Novel’ is described as a thriller, and I should have stopped there. The lure of Spinoza was, however, too much; I bought it and started to read. The book has two characteristics that I dislike so much that I gave up on Spinoza.

First, everything is written in the present tense, including flashbacks. Ergo everything is happening at once.

Second, this simultaneous action occurs across the centuries because every other chapter alternates from Spinoza’s time in the 17th Century and the 20th Century. I like my krimis linear and literal.

The early scene with the schoolboy Alfred Rosenberg (look him up, if he is unknown) getting a lesson in life at his Estonia high school is certainly interesting, and sheds some light on anti-Semitism. I wish I had been able to persist,,,, (However, there are so many other, good books that do not set my teeth on edge.)

The use of the present tense is so common I suspect it is advised by agents and perhaps required by publishers, at least, of certain genres. That is, the thriller. Why do I react to it?

When everything is happening at once, it is left to the reader to sort out sequence, to distinguish past from present, and to supply the emphasis and the pace of events, and even to supply the viewpoint. It is like looking at two-dimensional flat world without topography and without time. See, it is lazy writing making the reader do the work that the writer should have done. Stephen King would have a zinger on this. Verb tenses are tools, and should be put to work. That is why they exist.

Not everyone is bothered by ahistorical simultaneity, it seems, because the book is published by a major New York publisher and has a good rating on Good Reads, for whatever that is worth. (I never cease to marvel at the illiterate accolades heaped on some dreadful specimens. Why did Donald Trump come to mind?)

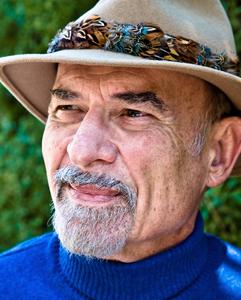

Irvin Yalom

Irvin Yalom

Confession: I was also irked by a lengthy introduction from the author about his many and deep interests. If that has to be present, put it at the back. In any event, I skipped it, something I was taught to do in college literature classes so as to make up my own mind. That I did.

‘Lanterne Rouge’ (2013 ) by Max Leonard

Lanterne Rouge? Yes, it can be the red light on the last car in railway train, in the dark there to let yardmen, roustabouts, and switchers know that is the final car. It can indicate a doctor’s late night surgery in some countries, and…., well, you know. (I only know from movies.)

In this case, none of the above!

The Lanterne Rouge is the last rider to finish the Tour de France, and Max Leonard, himself a cyclist, wondered how those losers felt about being last.

I am glad he did, because their lives, races, and attitudes are varied, intriguing, and represent much of the Tour de France at its best and at its worst. Moreover, Leonard has a light touch with self-deprecating humour, as he rides them down.

Perhaps the most important point made is that to finish last in the Tour de France is not losing!

Counter-intuitive, but true all the same.

When one Spanish rider was asked by a boneheaded journalist, is there any other kind, how he felt about finishing last, this was his reply: ‘One hundred and ninety-eight riders from the cream of world cycling started the Tour and I finished (stress, finished) at 120.’

Explanation: Seventy-eight others did not finish, but he did. To do so he had to make the time cutoff each day to stay in the race, not easy that, period. He coped with mechanical breakdowns and stayed in the race. He managed injuries from falls and stayed in the race. All the while he performed his role on the team, carrying water bottles for others and pacing the sprinter. He climbed the mountains in the Pyrenees and the Alps, endured the individual and team time trials, pedalled the long flats, and coped with the weather. Hard. Hard. Hard.

It is a theme that recurs. Finishing is itself a triumph, over the elements, over the odds, and over one’s own weakness, capped by a roll down the Champs Elysee with family and friends on the sidelines among the 100,000 spectators and millions more on television!

Sometimes it is a triumph over injury, as one Lanterne Rouge rode the last eight days in a neck brace, others with enough stitches to bring tears to one’s eyes. All of them overcame the inner voice that urged them to quit on the slope of L’Alpe d’Huez, half-way through a 60-kilometer time trial, while riding last through a parallel rain storm off the Atlantic, or on a hairpin-turn descent. For many it was the dream of lifetime fulfilled to ride in the Tour and to finish. Period.

Further proof, be it needed, is in the person of Jack Durand, who finished last and yet stood on the winner’s podium on the Champs Elysee! Huh? He was awarded the medal for the Most Competitive Rider.

Through the three weeks of the Tour he led one attack after another, on climbs, in the flat, against the wind, through tunnels, often alone. On some days he led the field for a 50 kilometres. Some of breakaways produced a gap of 12 minutes. Some days he pedalled quietly in the peloton. He was unpredictable and explosive. His post mortem was this: ‘Everyday I ride to win. Against such champions as gathered for this race, I have to beat them mentally with breakaways.’ Indeed he did win a stage in that tour.

Then there is Phillipe Gaumont who became a (barely) riding chemistry laboratory. He surrendered to Dr Alchemy, and rode on Belgian Pot, a concoction of cocaine, blood stimulants, and anything else lying around the laboratory. As he slowed down, he took more needles, the syringes taped to his ankles inside his socks. The effect was curvilinear, at first he was stronger, then he plateaued, and then he slowed, as he slowed, he shot up ever more drugs in the hope of regaining speed, but instead that slowed him down even more and he could barely finish. Thereafter he broke down, and shortly thereafter told all in a memoir. He died at 44, surely the chemical soup hastened the end.

Max Leonard

Max Leonard

These stories illustrate the material. In its one hundred editions, there has always been a Lanterne Rouge, and there are more of their stories in the book. There are many ways to be a lantern rouge in life and it does not mean being a loser. There is a moral in there somewhere.

‘Entanglement’ (2010 ) by Zygmunt Miloszewski

This in a police procedural in a series following the investigations of Polish State Prosecutor Teo Szacki. In Poland, according to this novel, the prosecutor does the investigating, and not the police whose domain includes the heavy lifting and car chasing. The locale is Warsaw with its nouveau riche and old communists side by side. It is part of series.

A middle aged man in mid-career is found dead in a church, a shish-kabob skewer stuck through his eye. He was participating in a role-playing therapy group using rooms in the church. Between sessions he was murdered. Did someone take the role playing too seriously! Was there an intruder? Did the victim have an enemy who followed him there? Did he — somehow — commit suicide with that skewer?

Most of the role-playing was videoed and much of the early going is Szacki watching it with the therapist who explains the proceedings, while more than once, Szacki thinks about his own life and his own need for…something, perhaps even therapy. The theoretical explanation of the procedure seems incredible [no spoiler] but it hangs together (and adds to the mystery, which is often lacking in krimis.) In addition, the victim also recorded some of his musings on a pocket recorder, and these, when discovered, add to the incredibility of it all, because he seems at one point to be talking to a ghost.

The more Szacki digs, the more confusing and paranormal it seems to become. This mystery is not welcome to a man who lives on and for facts.

Warsaw is new to me and I enjoyed the to’ing and fro’ing around the city in the summer rain. The banter between colleagues in the prosecutor’s office, the lack of a budget for even basic tests, the vulture journalists looking for blood, the boom-and-bust all at once nature of contemporary Poland while the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, and the role-playing therapy, these are all well handled and add layers to the narrative texture.

Zygmunt Miloszewski

Zygmunt Miloszewski

There is a plot wobble for this reader. Szacki seeks a second professional opinion on the therapy session and that confirms the procedure, but later…. Well, no spoiler but the curve disappointed this reader.

While the author distinguishes the characters, as always with such unfamiliar names, I found keeping the names and the individuals straight difficult. Though I consumed those dark, depressing, and dispiriting Russian novels that were de rigueur in college, I could never keep the names straight then either.

The translation and presentation on the Kindle are good. The production is far better than for the other Polish krimi I recently discussed, ‘Polychrome.’