John C. Breckinridge (1821-1875) was born to very comfortable circumstances in Kentucky. He was educated at the College of New Jersey (Princeton) where his father had many family members. Upon his return to Lexington, the young John Breckinridge went west to make his name and fortune to Burlington of the Iowa Territory where he was a lawyer to whom professional success came but slowly. Thus he spent formative years outside the slave-holding South.

He was erect, tall, courtly, well-spoken and thus invited to speak at a 4th of July occasion, where he struck the right note and that earned him both more speaking engagements and clients. His law partner, much like that of Abraham Lincoln, complained of Breckinridge spending too much time politicking and not enough lawyering.

By the way, one reason why the young Breckinridge found it easy to leave Lexington Kentucky for Iowa was that a girlfriend jilted him, she being one Mary Todd, later to wed the aforementioned Lincoln.

Though slavery was the issue that governed his life and everyone else’s at the time, he apparently had no particular opinions about it, one way or another. While he was not slaver, he did not oppose it. On every occasion he always sided, ultimately and if sometimes reluctantly, with the slave states on Lockean grounds of the absolute right of property. By the way, religion does not figure much in his life as told in these pages.

Breckinridge returned to Kentucky, the Iowa excursion had always been intended to be limited, and had more success, professional, political, and social in the Bluegrass State. His public speaking on patriotic occasions made his name known.

He served in the Mexican War, where he showed concern for the troops in his command, and learned the need for staff work to secure supplies, food, harnesses, boots, forage for animals, and medicine. These lessons he would use later in life. He also met the whole gamut of officers who would later figure in the Civil War. The list is too long to repeat here, but it included Hiram Grant and Robert Lee.

While in Mexico he defended an officer falsely accused of crimes. The accusation was hatched as a way to undermine the general commanding, Winfield Scott, whose presidential ambitions were plain to see. This was in hindsight a political conspiracy to hamper Scott’s presidential ambitions. But Breckinridge seems to a have taken it at face value. His defence was finely judged and widely reported and successful, giving him a national profile.

His service in Mexico was after the hostilities had ceased but before the treaty was signed, ceding California and New Mexico. Ergo there were still tensions and alarms, but not cannon fire. Unlike all those other Civil War generals, he did not attend West Point, and later learned to be a general on the job.

In the late 1840s and 1850s the Whig Party was destroying itself by infighting, and Breckinridge aligned himself with the rising Democrats. He vigorously campaigned for others, and in time won a seat in the Frankfort legislature. His public speaking is much emphasised. In these speeches he always took a positive tone and spoke about what was necessary, what he could and would do, and made it a point not to disparage his opponent(s). My, my that is lost art, emphasis on the positive.

When Abraham Lincoln visited his Todd in-laws in Kentucky, he met Breckenridge and thereafter they had an occasional correspondence, e.g., when one won a case reported in the press, the other would sent a note of congratulations.

As the Great Compromiser — Henry Clay, a Whig — lost his grip on Kentucky, growing old and frail, and because his party was eating itself, Democrats filled in the spaces available. Became of his attractive personality and eloquence, Breckenridge was pushed to the front. Clay seems almost to have endorsed him, despite the party differences, for they were often seen together.

In the state legislature Breckinridge was a dynamo for local improvements, from schools, roads, bridges, streets, public buildings, and so on. His staff work in Mexico had taught him the importance of detail and he applied this lesson in the legislature, while many others were satisfied with oratory, and though he was exceptionally good at that, he went beyond it to get the details right.

He married but his wife and family seldom figure in this account.

Unusual for the time, he had lived in New Jersey while in college, Iowa as a young lawyer, and being personable, attractive, and sociable, he made friends where he went and keep in touch by mail. His army service added to his contacts and gave him national publicity. As a budding Congressman, both Henry Clay and Stephen Douglas saw great things in him and said so. He campaigned for others in surrounding states.

As a state Legislator and later as a Congressman, he was a mediator. Where there was a deep divide, while keeping his own counsel, he was trusted by all to understand their positions, if not agree with them, and he would confer widely in search of some common ground.

There was only one issue: slavery, masked by states rights and the Constitution. Breckenridge played a key role in the Kansas-Nebraska Act. However much or little common ground Breckenridge could find in the wording of this resolution or that, it was never enough to paper-over the chasm of slavery.

He campaigned hard for Franklin Pierce in 1852, speaking three or four times a day in five states. While his speeches praised the Democrats, he did not belittle nor insult opponents, and generally struck a positive note, which increased the invitations to speak.

Pierce, whatever his merits, became the first, perhaps the only, incumbent president to try and to fail to secure re-nomination by his party. Though Breckinridge supported Pierce for re-nomination, when Pierce was eliminated, Breckinridge turned the eventual nominee, James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, who wanted a southerner on the ticket and one who was presentable to all regions, ego he tapped Breckinridge, though the two had nothing in common and had met but once, briefly. (Pierce never forgave him this switch, though Pierce had no chance of renomination.)

In those days the candidates retired to their homes and did not campaign, leaving that to others, and from this practice party organisations emerged. ‘Buck and Breck’ won for the Democrats.

Breckinridge had the same relationship to President Buchanan that all Vice-Presidents have with all Presidents. None.

Though the country was boiling with dissension and the parties were cracking along geographic lines for the first times, the Pennsylvanian Buchanan did not ask the Kentuckian Breckinridge to attend cabinet meetings. Indeed they had exactly one private meeting and that was in the last year of their term about a triviality.

Buchanan was unmarried and solitary by nature. Accordingly, he delegated ceremonial and social tasks to Vice-President Breckinridge, e.g. receiving ambassadors, hosting functions, addressing celebrations, all of which expanded Breckinridge’s horizons and networks.

His main duty was to chair the Senate and he did this scrupulously, unlike most of his predecessors. He was impartial in the chair during heated and intensely partisan debates, but more importantly he spent much time talking to senators before the debates so that he knew what to expect. Ever the mediator, he often was a go-between used by factions and parties to communicate with each other and at times he found that undiscovered country. – common ground to smooth over the crisis de jour. Even that most stalwart and violent Republican, William Henry Seward praised Breckinridge’s management of the fractious Senate for four years. It may be the only time Seward even publicly said a good word about anyone.

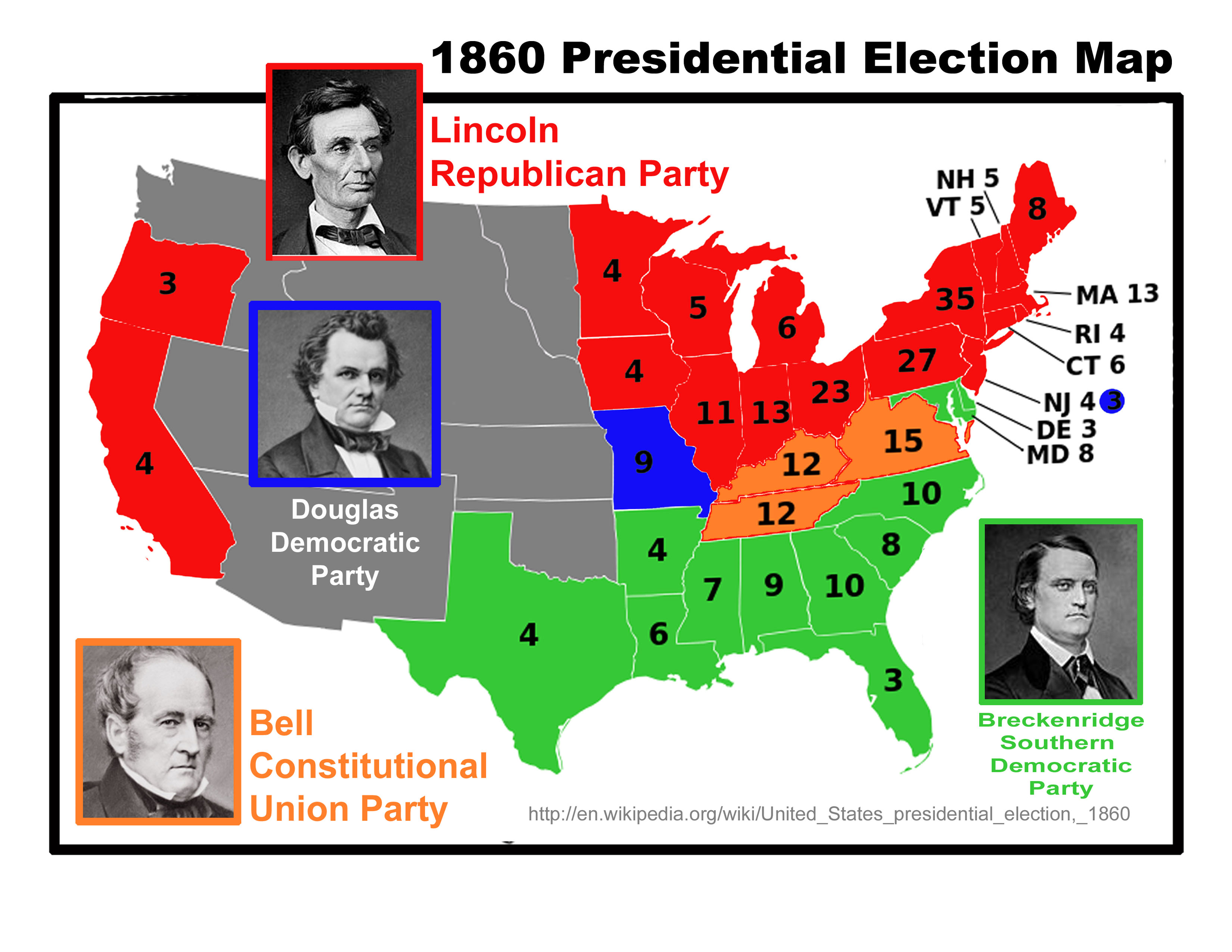

The machinations of the 1860 election are many. The Republicans put up an obscure western lawyer named Abraham Lincoln. The Democrats split along the geographic fault line of Mason-Dixon with Stephen Douglas as the northern Democrat candidate whom southern Democrats distrusted. John Bell became a third party candidate appealing for national unity in the border states like Kentucky, Delaware, Maryland, and Missouri. Southern Democrats nominated Breckinridge, and he accepted. But why?

Splitting the anti-Republican vote would insure that Lincoln was elected, and Breckinridge accepted the nomination precisely to avoid that split. How so? Pay attention now, class, this is today’s lesson.

Once Breckinridge was in the field, the hope was that Douglas would realise he could not win. Then the three candidates — Douglas, Breckinridge, and Bell — would meet and agree to withdraw in favour of another candidate and several were lined up, or the other two would withdraw in favour of Breckinridge. Note that Breckinridge did not seek the nomination in the first instance thinking it was inconsistent with his duties as Vice-President. Odd that. But he was certainly flattered to be nominated.

This plan never flew. Douglas made it clear that he would not withdraw and the four-way race ensued. By then it was too late for Breckenridge to withdraw.

The author makes a good point when he lists those who voted for Breckinridge, which include Robert Lee, Hiram Grant, Jefferson Davis, and Benjamin Butler. The point is that Breckinridge was a national candidate, as well as a regional one. He got votes in Massachusetts, Ohio, Virginia, and Tennessee. But it is also true that his vote was concentrated in the South and he carried all the slave state and Delaware, apart from Tennessee, Virginia (both taken by Bell). and Kentucky (ironic that, and shades of Al Gore) which also went to Bell. (Despite 30% of the total vote, Douglas won a majority only in Missouri.)

As the sitting Vice-President he organised the inauguration of Lincoln. He had won election to the Senate and while other southerners left as soon as Lincoln won in November 1960, he stayed after Fort Sumter in April 1861 and even after Manasses in June 1961. He was trying to calm things down but he gave up.

Meanwhile, Kentucky, divided between unionists and secessionists, tried to be neutral as the war started. But eventually Grant’s army crossed the Ohio River to Paducah, and in response a Confederate army entered eastern Kentucky. Breckinridge then returned to Lexington and accepted a commission from the secessionist governor in the state militia. Quite why he went grey and not blue is not very clear. Most of his relatives were secessionists, but not all, but in confusing times that is what he did, and once comitted he stuck it out.

He was now the soldier of the subtitle. He learned on the job, and learned quickly, but he did make mistakes. Braxton Bragg hated him, but Bragg hated just about every other officer in the army.

He served in a variety of places, including Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, West Virginia. He took part in General Jubal Early’s 1864 raid on Washington DC and his troops shelled Fort Stevens while Abraham Lincoln watched from the ramparts, those two presidential candidates meeting again at this distance during a barrage.

In desperation, President Davis appointed him Secretary of War in early 1865, and he became a statesman again. This part of his career is the subject of another book reviewed elsewhere on this blog, namely ‘An Honourable Defeat.’ Here it suffices to say that it was his finest hour. He did much to bring a lasting peace.

His health was broken by the war years, and when he returned to Kentucky he eschewed public life, refusing even President Grant’s suggestion that he re-enter political life. But he became a symbol of one who accepted the defeat and looked to the future.

William C. Davis

William C. Davis

The book is meticulous and informative. The last chapter offers a very good summary and judgement of Breckinridge’s careers as statesman, soldier, and symbol of the Confederacy best elements.

Author: Michael W Jackson

Gao Wenqian, ‘Zhou Enlai: The Last Perfect Revolutionary’ (2008)

Zhou Enlai was a name and face on the news when I grew up, first a menace and then a calming influence. Yet I know next to nothing about him. In English this title implies it is a biography, and so I chose it. Later I discovered that it’s original title in Chinese was about his last years, and this latter title is descriptively accurate. It is an account of the last years of Zhou preceded by a perfunctory description of his formative years. Nothing in the book bears on that phrase ‘perfect revolutionary.’

There is no doubt Zhou was cursed to live in interesting times. In his youth he spent a year as a student in Japan. But he got the political bug and became a lousy student. He then went to France ostensibly to be a student again, but really to join the surprisingly large group of Chinese exiles organising themselves there. It was five years or so. Many people he met there became major figures in subsequent Chinese politics mostly communist. He did not meet, according to this accord, Nationalists like Sun Yat Sen who was in the States, I guess. Nor André Malraux who was in China at the time.

When the Comintern ordered that the Communists cooperate with the Kuomintang (Nationalists), Zhou worked with and got to know others like Chang Kai-Shel and the later Japanese invasion. The Comintern promoted a popular front with the Kuomintang for years, even at the expense of the Communist Party of China. This shotgun wedding only ended when Hitler invaded Russia and distracted the Soviets.

Zhou very soon became number two to Mao, and stayed there for the rest of his life. He was a trimmer, that being the only way to avoid Mao’s wraith. Though the author admires Zhou, there is no doubt that Zhou looked away at some of Mao’s worst excesses including the Cultural Revolution.

Life with Mao seems like Orwell’s ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’ to the Nth power.

Most of the book concerns life on the greasy pole in Mao’s China. Mao is portrayed as a paranoid egomaniac who treated people like disposable chess pieces, and who was culpable in Zhou’s premature death. The bulk of the text describes this meeting and that, particularly before, during, and after the Cultural Revolution, all very Orwellian or very like North Korea today.

None of this endless detail fleshes out Zhou the person or deepens insight into him. I never felt I got to know anything about him except that, whatever he thought to himself, he never said, and instead fawned over Mao as the only likely path of survival. It reminded me of reading the memoirs of the elder St Simon who spent eighteen years at the court of the Sun King and who wrote in his compendious and secret memoir that in those eighteen years he never once said what he really thought to anyone, though he talked to everyone everyday all day in the court ritual. No doubt St. Simon lavished praise on Louis but Louis was not as bloodthirsty as Mao.

The book is vague. I will offer only one example of scores that could be cited. The author will say that ‘Zhou handled this problem in his usual smooth way.’ How was that? I would like to know more detail in these hundreds of pages.

Gao Wenqian

Gao Wenqian

The book has too much and too little detail. It has too much detail about this and that plan and plot, the wording of this report or that, and too little concrete detail about what Zhou did that made him so successful and valuable even to Mao. Occasionally the author says Zhou used his usual skill to do this or that. What skill is that? Not enough explanation, e.g., to crush his opponent Mao used the ‘heavy artillery,’ huh, meaning what at a party conference.

So many personalities appear that escape a general reader like me.

The text is both wordy and cryptic. That is, it is wordy and not concrete. I never did form a picture of what Zhou did. The slang-filled translation is no help, e.g., ‘good guys,’ ‘pals,’ ‘hot potato.’ and much more. Though the book is too detailed for a general reader, it is replete with this lazy slang.

Joanna Jodelka, ‘Polychrome’ (2013)

An elderly man in Pozan Poland is found murdered. The more closely the investigating officer, Mariej Bartol, examines the scene the odder it looks. The victim is posed, naked, and almost seems to be smiling despite the strangulation. Then there are the Latin mottoes found on the flower vase, inside the bow of a pair of glasses. Enough to set one to thinking.

Then a second man is found, also posed, also with a few Latin mottoes discretely tucked around the scene.

We get quite a bit of the personal life of our hero, and his mother is some character. But it is laid on with a sledge hammer.

Our hero seems to have been born dumb and misses the obvious a few times.

On the other hand the officers he works with are well drawn, and there is much to’ing and fro’ing in and around Poznan in a wet spring. It has some sense of place.

Then there is the Latin scholar he recruits through his mother’s contacts to make sense of the tags. She is a firecracker from go to whoa, and our hero suffers a rush to blood to his first friend, making him even more slow-witted than usual.

I read it on the Kindle and it was not easy. There were odd font characters, broken lines, run-on paragraphs, spelling errors, and more. The translator into English seems to be a Pole, and I guess that explains the syntax errors and the unfathomable idioms which may make sense in Polish but do not in English. Maybe the translator once worked for Jimmie Carter. (Either you get it, or you don’t.)

Joanna Jodelka

Joanna Jodelka

Before trying another one of these I would want some reassurance that editorial improvements had been made. On Amazon the paperback is $0.08 which is less than the Kindle version. Not sure what to make of that.

It is a double whammy, a lousy presentation and badly translated. It was too much like reading student essays. There were students of my acquaintance who thought that if the work they submitted was incomprehensible, then the instructor — moi — could not fail it. WRONG! They would then challenge me on the ground that their paper was…, yes, incomprehensible, and since I did not therefore comprehend it, I could not honestly fail it. Imagine the time I spend in such conversations. Now it is easy to see why retirement has its attractions.

For what is worth and to balance the books, I had more than one similar conversation with a Ph.D.-bearing lecturers who asserted, no evidence required, that their lousy teaching stimulated students to learn for themselves. This was no argument about the meaning of lousy teaching, they admitted it and celebrated it. Needless to say these individuals all prospered. What did I say about retirement?

The Bette Davis Club (2015) by Jane Lotter.

Or, Margo’s adventures through the money glass. Reluctantly, Margo goes to the wedding of her niece, and the fun begins in Hollywood. The spoiled bride bolts, and the vampire mother of the bride makes Margo an offer she of near bankruptcy cannot refuse and a black AMEX card! She throws in the keys to a red MG and the groom! Who knew such cards existed? Not us plebs.

Off they go down Route 66 meeting all kinds of people, some of the most memorable at the Lesbian dance contest in Palm Springs, others with whom they exchange insults over breakfast, a kindly woman who presses a marriage manual on Margo, and Boone who seems destined to be in recovery from head injuries. He should have stuck to football.

Cary Grant even puts in a cameo appearance,. This book has it all, and more!

Finding the bride, after all this, is anti-climatic. She is a brat.

Margo’s confession at the meeting set a new standard. Indeed. No spoiler here. Find out for yourself.

Along the way the imbecilic nature both of Hollywood and its audiences are noted.

Margo is wrong about almost everything but soldiers on. She may be broke but it is not from a lack of effort.

It shifts gears from silly to serious and back several times but the mix is well judged.

Jane Lotter

Jane Lotter

I was very disappointed to learn it is a once-off.

‘Letters to Pastor Jaakob’ (2009)

A little gem from Finland. A blind Lutheran priest takes on as an assistant a paroled murderer, Leila. Father Jaakob has a reputation as an intercessory, I.e., he prays for people and offers advice to those who write to him. While no time period is given it looks like the 1950s. He lives in a forest near a church on a lake. Nature dominates the time and the day.

His only contact with the outside world is the post and the postman. The pastor has long since given up preaching because of blindness, and he lives for those letters.

Leila is angry at the world and makes no effort to cooperate though she is glad to be out of the slammer. She is neither particularly bright nor attractive, and expects people to dislike her. They oblige in the person of the postman.

At first she thinks either the priest is shamming or is a fool. In time she comes to respect, if not share, his faith in a meaningful world. Or so I surmise because the dialogue is like much from Finland, practical and not introspective. And there is little of it. Much is told by the camera.

She also realises that he needs her if he is to live – she reads the letters to him and he needs those letters, just as the writers need him. And she also learns she owes not only her freedom to him, but more, too. No spoiler. His previous letter-reader left for the city to take care of grandchildren.

For some reason never explained the letters dry up and that brings the needs of each to the forefront. Earlier she destroyed some of the letters and perhaps his consequent failure to respond to those, discouraged others from writing. It is not clear, nor need it be. Little of life is that, clear.

In fewer than eighty minute there is more about life in this film than the latest CGI-infected three hour Hollywood brain-buster.

Klaus Hãro, the director.

Klaus Hãro, the director.

It earned place on my list of Finnish movies along with

Leningrad Cowboys (1994)

The Man without a Past (2002)

Vares (2004)

The House of Branching Love (2009)

Rare Exports (2010)

Midsummer night’s tango (2013)

Top marks must go to ‘Rare Exports.’

Ian Samson, Death in Devon (2015)

This krimi is a light-hearted romp through distant Devon. This book is second in series not first. My mistake.

Our hero, Sefton, is amanuensis to Morley, an H. G. Wells-type, in 1938. The know-it-all Morley is author of endless titles including a series on English counties. Nice set up.

They fetch up at a school where Morley has been invited by an old friend to give a lecture, and there they find strange doings. Alex, the handsome and confident head teacher, has a plausible explanation for everything, but, still, Sefton has doubts. He also is jealous of Alex’s designs on Miriam, Morley’s daughter, who drives the Lagonda on these excursions. She, for her part, seems to welcome these designs.

There is a death, claimed to be an accident, of one of the school boys. Animals disappear from a nearby farm. Strange noises in the night are reported.

Sefton is, of course, right, and for all his blather Morley is quick thinking and acting in the crisis.

That makes it sound better than it reads, I confess. Many, very many, altogether too many of the pages of the first two-thirds of the book are given over to Morley expatiating on endless, irrelevant subjects. Exhausting. Pointless. Did I say, tiresome. Morely is an expert on everything and has to prove it minute-by-minute.

At the outset I compared him to H.G. Wells because of that know-it-allness, and the endless list of his book titles, but he is not as pompous and self-important as I suppose Wells was. I say that because I suppose some of Wells’s book have an autobiographical element, e.g., ‘The New Machiavelli.’

The three principals are likeable, the set up is clever, and the place, Devon is different. There is some mis-direction about those caves that keeps the suspense alive. But Morley droning on, while Sefton mentally footnotes the drone to his list of publications, is deadening.

Ian Sansom

Ian Sansom

Loved his bad books library series set in Northern Ireland.

‘Dag Hammarskjõld: A Life’ (2013) by Roger Lipsey

In sum, this book, despite the subtitle, offers very little about the boy, adolescent, young man, or adult. Hammarskjõld was born to the purple. He grew up and lived most of his life to twenty-five in a palace in Uppsala, that being the official residence of the provincial governor, his father. However the book is excellent on his tenure at the United Nations.

He had little international experience but some on a Marshall Plan Committee as an economist. Because Swedes did not receive Marshall Plan monies they were trusted to allocate and manage it. Hammarskjõld had been an economist at the Bank of Sweden and done some international negotiating.

There is nothing about his life, experiences, or attitude to World War II. Why and how he learned English is not discussed. He also spoke German.

Trigve Lie from Norway was the first Secretary-General and he had taken sides in the Cold War, though he wanted a second term, the Soviet bloc was alienated.

The next Secretary-General had to be a neutral. The less experience the better, so as not seen to be committed or to have baggage.

Hammarskjõld entered as completely into the job as if he were entering a monastery. He sworn and oath to the Charter which thereafter he carried on his person for ready reference, yes, but also as a document to venerate. There is a spiritual quality to his commitment.

No women. No significant other of any kind. Though many rumors about homosexuality.

His life was monastic. He got by on three to four hours sleep most of the time. In a deep crisis like the Congo, less and in quiet time little more.

At the United Nations he relied heavily on Ralph Bunch, first for internal administration and management and later as a deputy diplomat. (Maybe I should read about Bunch, this extraordinary individual.)

‘Markings’ Hammarskjõld’s personal notebook reveals the spiritual inner man who communed with the writings of medieval Christian writers. Much of this book and consists of musings on Hammarskjöld’s musings in ‘Markings.’ Hundreds of pages. All too much musing and not enough narrative.

Hammarskjõld had tall poppy cutters in Sweden who made career out of criticising him. Newspaper editors, who extended their animosity to berating the posthumously published ‘Markings.’ It is good to know that Australian media ethics are in such good company in the gutter.

Some of Hammarskjõld’s speeches are fabulous. Lucid, clear, targeted at the next step, infinitely patient, aware of the pressures on others, but punctuated with some elevated words to inspire. He seems to have gotten better and better at this rhetorical skill in the UN. It is not something he had any previous experience or preparation to do. They read well, though I have no idea how he delivered them.

Hammarskjõld more or less created the role of the international civil servant, and reflected on that, especially in the in-house speeches and reports to UN staff.

He had some successes in meditating conflicts, like the Suez Crisis in 1956. Then came the big one.

The Congo consumed him even before he died there. The endless fragmentation, the intervention of Europeans to support the Belgians who did not want to leave, and the tribal and regional violence armed by the Soviets, the CIA, Belgians, South Africans…. were let loose. The single Congo became two, then three then four entities each with its internal constituencies, that is tribes, and external supporters, and all armed to the teeth.

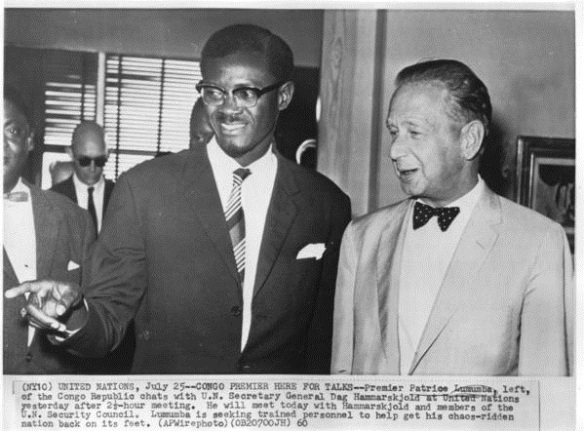

Patrice Lumumba is the most interesting of the characters in the Congo. He was an articulate idealist who seemed to have been able partly to bridge some tribal differences. He was a rabble rouser on radio and in person. But he had no ability to work with others in committee, completely useless as an administrator, and he had no competent second to cover these things. He was a front man only with no band behind him. He could arouse a crowd but he could not lead it anywhere. His only message was to reject the Belgians and as they left the vacuum was filled.

Dag Hammarskjõld and Patrice Lumumba

Dag Hammarskjõld and Patrice Lumumba

There is much about Hammarskjöld’s death. Hear-say, secondhand, and some alleged eye witnesses who feared to speak at the time and who now cannot shut up thirty years later. All the so-called doubts seem to me to be speculation. If any other death was raked up thirty years later it would be the same.

There was a lot of mission creep in the Congo, despite his efforts to limit it. It went from peace-keeping to, since there was no peace, peace-making.

Roger Lipsey

Roger Lipsey

The book is far too long and there is just too much musing for a biography. Moreover, there is precious little biography of the boy become man in Sweden. It is a reflection on Hammarskjõld’s tenure as Secretary-General, and it is good on that. But despite the many musings on Hammarskjõld’s musings, I never did feel I was getting close to the inner man. I did feel impatient more than once.

The dissolution of the Belgian Congo was a grim story that occupied the television news every night, and it consumed a lot of good men and women. When I looked for a biography I found many on Hammarskjõld’s death, conspiracy theories, ‘now it can told,’ sort of titles that seemed to be ghoulish attempts to capitalise on his death. All in the spirit of Jim Garrison (for president) on JFK.

William Dietrich, The Trojan Icon (2015)

This is the eighth outing for Ethan Gage that energetic Eighteenth Century rogue. While I have enjoyed most of the books in the series, once again I had the feeling that the the wind is leaving Ethan’s sails. This title is much slower and more serious than its predecessors. Ethan does not sparkle. He worries a lot. The word ‘again’ refers to ‘The Emerald Storm’ (2012) which seemed more a forced march than a romp.

![]()

Moreover, the narrative is divided between Ethan and Astiza, his wife, and she is even more serious than Ethan has become because she worries about their son Horus (Harry) who also has some chapters, consisting chiefly of him worrying about his mother. There is a lot of worrying. These three worry enough to be Op-Ed writers, that professional worrying class.

The technique of alternating chapters with the voices of Ethan, Astiza, and Horus slows the pace a lot. And it is distracting. Especially Horus, the eight year old whose range is, well, that of an eight year old.

On the other hand there are vivid characterisations of the many individuals and the places that Ethan meets and traverses but once again it was too much, St. Petersburg and the Russian court, Poland and a revanchist noble, Istanbul and the the harem in the Topkapi. Indigestion, I cried. All of this name and place dropping is not a substitute for élan, spirit, movement, and fun.

Yet for all the movement there is none of the pace that I have so enjoyed in some of his earlier titles in this series. In these pages the movement is punctuated by long periods of rest and relaxation. and, of course, worry.

One character drops out of the story half any through, namely the Russian prince, whom I keep expecting to re-appear, as others do in this novel and have in the others in the series, else why have him in the first place. Answer: a plot device.

It is peopled with some truly malign villains, von Bonin and Count Dalca. Neither one is a quitter, that is for sure.

The eight Ethan Gage novels.

1 Napoleon’s Pyramids (2007)

2 The Rosetta Key (2008)

3 The Dakota Cipher (2009)

4 The Barbary Pirates (2010)

5 The Emerald Storm (2012)

6 The Barbed Crown (2013)

7 The Three Emperors (2014)

8 The Trojan Icon (2015)

I found ‘The Emerald Storm,’ despite its exotic setting, to be forced as I found this title to be. I read this one on the Kindle. I do hope the author consults Alfred E. Neuman before he writes the next one follows Neuman’s timeless advice ‘What, me worry?’

Non-entities to the left and to the right.

The increasing polarisation of politics in the United States has many consequences that are less visible than the entertainers vying for presidential nominations.

One long term consequence that has infected both Republican and Democratic administrations has been the selection of appointees. More than once able candidates have demurred or declined, while still others have been blocked in the Senate, or raked over the coals there so comprehensively that it becomes impossible subsequently for them to do the job. The Cold War custom of appointing as Secretary of Defense someone the other party, i.e., a Democratic President appoints a Republican as Defense Secretary has become nearly impossible. For a Republican to accept an appointment in a Democratic administration is now Tosca’s kiss. Secretaries of the Treasury were often appointed in the same way. But no more. As were ambassadors to particularly important posts. There was in short a bipartisan approach to some matters regarded as above politics.

It is routine for the fourth or fifth choice to be selected, because choices one through four feared the nominating process.

The endless media scrutiny starts long before the name is finally said, ignited by rumours and trial balloons. That however is nothing compared to securing the advice and consent of the Senate. Whereas for several generation the norm was that the President choses, and the Senate advises what it thinks, and then consents.

Not so any more. The threat that the Senate will not consent is palpable. Each side will say the other started it.  The Senate playground.

The Senate playground.

Every Republican Senator knows that to vote for one of President Obama’s nominees will stimulate an attack from the Tea Party, and may lead to a challenge from within the Republican Party. Senator Richard Lugar cooperated with the Obama administration to speed the disarmament of Soviet missiles left in Eastern Europe, to keep them out of the wrong hands. Seemed like a top priority at the time. Still does. But Lugar was a Republican and when he came up for renomination his Republican rival painted him as Satan incarnate for supping with the black devil in White House, and he won. So ended Lugar’s career. By the way the same was true for Democrats during the Bush Administration, but it was less conspicuous.

The unspoken fact is that one president after another has chosen to avoid such a confrontation by selecting a certain kind of candidate. Since all this has come up, again, about the Supreme Court, let us take that example.

Whereas Supreme Court nominees were once leaders in the judiciary with widely quoted opinions, long and closely argued articles in premier law journals, keynote speakers at the most important legal conferences, reputations for analysis….and more. Not so any more.

The paper trail of such outstanding candidates is rich pickings for someone willing to misconstrue, misinterpret, and de-contextualize everything to settle old scores and to embarrass the nominator.

The result is the routine selection of candidates with a small paper trail because they are a smaller targets, not because they are better jurists.

This preference for ever smaller targets is now commonplace. The more obscure the candidate the better. While the Supreme Court is the big ticket in this game, it is not unique.

Cabinet appointments can also be vexed, as plenty of recent examples have shown. That the Senate consented to Hillary Clinton or John Kerry is due to their service as Senator. Like the media, the Senate does not (yet) eat its own.

Barbara Pym, ‘An Academic Question’ (1976)

Another gentle comedy of manners set among the red bricks of an English provincial university. Our heroine is Caroline, Caro, and her husband Alan Grimstone, who is a lecturer in anthropology at the aforementioned university. The social manners and morēs are very 1950s, though the time is the 1960s. The women are wives and the wives are housewives. Only widows and eccentrics are permitted to be exceptions.

Caro has little to do. Even less than some other faculty wives, because Alan does his own typing, in part, because he is secretive about his research. He is in competition with Professor Crispin Maynard who is head of his department in a narrow field of study, or so Alan thinks. The professor is more concerned with his grandchildren and dogs than with off-prints.

To fill in her days Caro reads to inmates at a nursing home, to call it by its right name, and one of them the Reverend Stillingfleet spent many years in Africa where he wrote notes about the natives’ manners and morēs. By using Caro’s reading as cover, Alan snitches one of Stillingfleet’s notebooks. It contains valuable data which he immediately incorporates into a journal article manuscript, the argument of which undermines the professor’s own work in the field.

Alan does offer the professor the opportunity to read the draft manuscript, but what with grandchildren and dogs, he declines. The clouds gather.

While Alan and Caro are still in possession of the notebook, Stillingfleet dies. Returning the notebook nows seems impossible so Caro keeps it, and Alan acts as if he does not know that, though of course he does.

Alan submits the manuscript and, voilà, it is accepted. If only it was ever that fast and easy!

He goes to London to correct the proofs to speed the process even more.

Caro moons around, wondering what to do with herself. She does not want a part-time job at the university library, which Alan thinks suitable, because she does not like the people in the library. She considers work in a jumble shop, but Alan does not find that suitable. This is a time and place when women often were introduced as ‘Mrs. Alan Grimstone,’ without even their own given name being, well, given.

She wonders if Alan is unfaithful to her, since he is often out at nocturnal seminars, and those trips to London to correct the proofs do go on. There are temptations in Iris, Inga, and Cressida.

She has some friends but they get on with their own business. Coco, Kitty, and Dolly, each seems to have a better grip on reality than Caro and they do buck her up from time to time. But well, Coco is a man who is apparently asexual, and with his mother, Kitty, together mentally they still live on the Caribbean island surrounded by servants as they were when Kitty’s late husband was governor, and so they are not entirely reliable. There is ever so faint an indication that Coco is homosexual. Dolly, who is Kitty’s down to earth sister, is the most practical person in the book, but she is rather obsessed by the life, loves, and deaths of the hedgehogs that inhabit her rambling garden. Any personal confidences shared with her inevitably are compared to the doings of the hedgehogs, which Caro finds rather…..

Alan admits a dalliance in London with Cressida, and expects their life to continue as before. He is man of his time and place, he cannot make tea, make a bed, prepare toast, etc. After retreating to stay with her mother and then sister a few nights, Caro returns to Alan and nothing more is said of the dalliance. Stiff upper lips and all that.

Alan’s paper is published, Maynard writes a rebuttal. Stillingfleet’s manuscript is lost to an accidental fire in the library to which he gave his papers, but the war of words between Alan and Maynard goes on in the pages of the journal, while they invite each other to tea at home and talk of the seasons. All very civilized.

Along the way, Alan asks Caro to do some typing for him, and she greets this as bridge between them. She will now be permitted to help him and take an interest in his work. He means it that way, and she takes it that way. I took it as satire.

Caro returns to the nursing home to read to others, and finds another elderly person with a trunk of papers….

There is a reference to Miss Clovis from Pym’s earlier novel, Less than Angels (1955). Some incidents seemed to set up for development in later novels, but this was her last.

Barbara Pym at the typewriter.

Barbara Pym at the typewriter.

The telling probably deadens it but in the reading it is light and breezy, and any members of a university or college department will recognise the types, the ambitions, the moans and groans of a nine-hour a week work-load, the quiet desperation of some women to breath in the manners and morēs of the time and place, the restive students….