Dear diary,

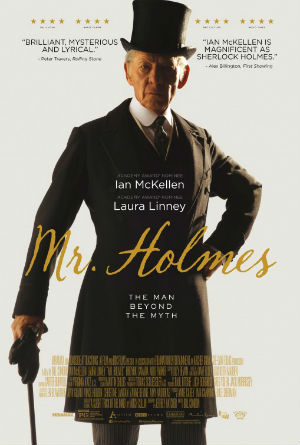

We went to see ‘Mr Holmes’ at the Newtown Dendy last night. I am glad we went but I found the film a disappointment. First, the molasses, and then the vinegar.

It was a pleasure to watch Ian McKellen hold the camera. Marvellous is this old trouper. And what knees he has for a man born in 1939.

The story does draw from the well of Sherlockiana. Holmes did retire to keep bees on the south coast near Dover. He did have a brother Mycroft whose reach was international. And there were nice touches, e.g., that 221B Baker Street was a false address to mislead curiosity seekers. The glass harmonica pricked my interest and off I went to Wikipedia to be informed. We also cackled at the film within the film, in part because it looked like more fun.

After Hamlet and Henry IV, Holmes must be among the most sought after roles in British drama. Yet having said that there is no Holmes from Laurence Olivier and the other celluloid knights. McKellen certainly lives up to the standard. It was because of him we went, as it was because of Robert Downey that we did not go see his 2009 travesty,

McKellen at 77 convincingly handles the various flashbacks and forwards from 93 to 58. Though what the point of the flashbacks and forwards was, that was lost on us. It just seemed pointless to put Holmes in Hiroshima. The film is based on the novel ‘A Slight Trick of the Mind’ (2006) by Mitch Cullen for those who want to make up their own minds. Perhaps it makes more sense there.

The supporting players were fine, though it was all so predictable. Mrs Munro was just cardboard. Full marks for transforming American beauty Laura Lynney into this Devonshire frump. Roger goes from monosyllabic to articulate in one scene. Me thinks also, the author of the screen play has not spent much time with the elderly. It is not just not remembering but not knowing that one is not remembering. When it is gone; it is all gone. One does not struggle to remember, rather it is gone without a trace.

The mystery of beehive murders, now that would certainly have been enough plot for a good film, about Holmes passing the baton — the deerstalker — to Roger, but that was nearly lost in the all the flashes this way and that until it was needed to find somewhere to end.

The setting along the white cliffs was nice but throughout the cinematography was washed out and blurred.

Author: Michael W Jackson

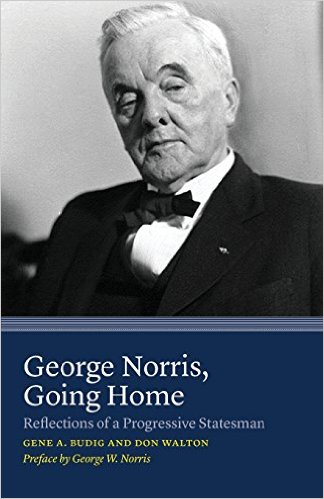

‘George W Norris’ (2013) by Gene Budig and Don Walton.

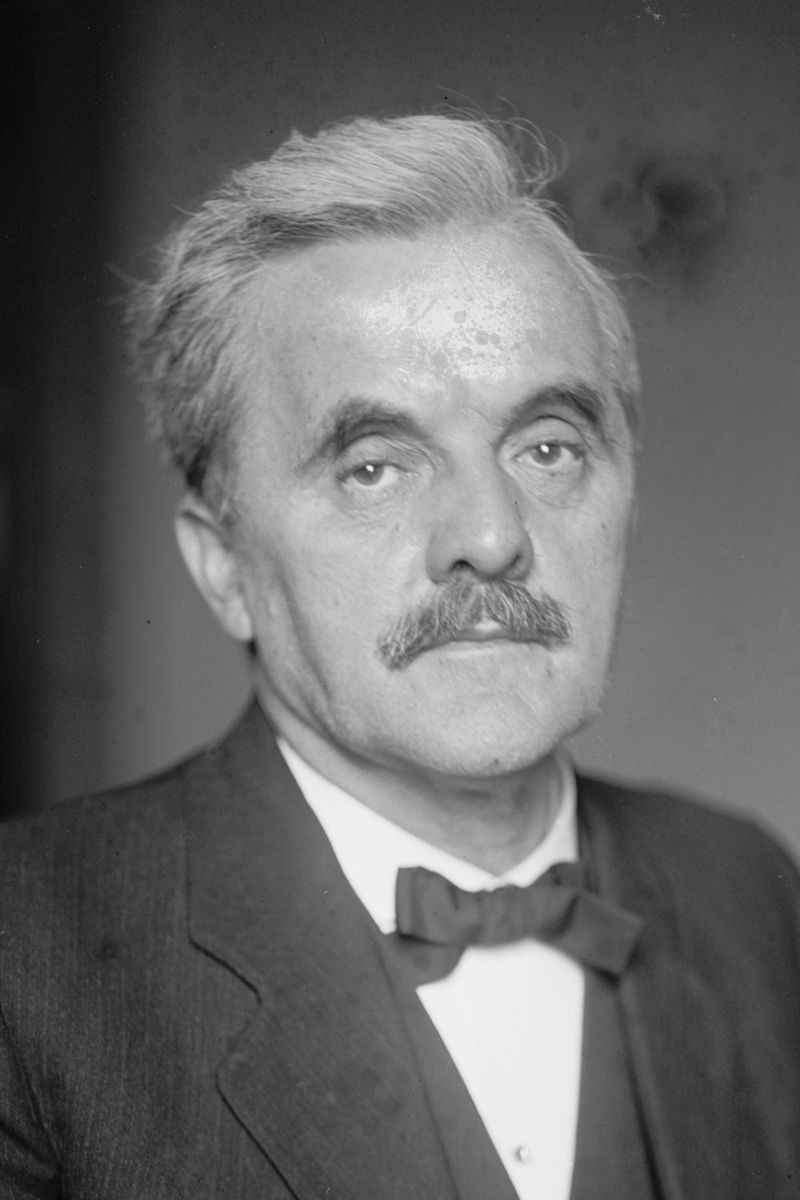

George W Norris (1861-1944) of McCook Nebraska did much to make the United States what it became. He represented the third district in Congress for ten years, winning five elections, and then went to the United States Senate where he served five terms, thirty years.

Published in 2013.

Published in 2013.

He supported and championed liberal and progressive causes, as did so many of his fellow Republicans in the era of Teddy Roosevelt, but if Republicans changed, Norris did not.

He left his mark in three distinct ways, one in Nebraska and the other two nationally.

1.During World War I the Federal government built a cataract of dams and power stations in northern Alabama at Muscle Shoals to power factories to produce munitions. At the end of the war, the assumption was that it would sold off for a few dollars to commercial interest who would exploit the complex of energy and factories.

But why should private corporations reap the benefit of the immense public investment in the complex, asked George Norris who then introduced a bill to have the Federal government operate the complex as a public utility.

This was socialism, cried the business interests, which grudging lifted the offered purchasing price a few dollars. Norris lobbied hard, bombarded the press with facts and figures during the Coolidge administration, and, because his opponents underestimated him, he secured a majority vote for his bill in the Senate. The first time it passed, it then died in conference committee with the House of Representatives.

George W Norris

George W Norris

Norris was seasoned and he knew that it would be a long road, so he was ready in the Hoover administration with a second bill, re-worded but with the same effect, and it, too, passed, and this time it passed the through the conference committee and went to the president who dealt it a pocket veto.

When Norris presented his third version, Franklin Roosevelt was president, and Muscles Shoals became the first brick in the Tennessee Valley Authority. The hue and cry over the TVA raged for years but it came to be. See ‘The Wild River’ (1960) for the human side of the TVA.

The TVA

The TVA

2. That the electricity produced by the damns sustained the second major theme of Norris’s career, Rural Electrification. Readers of ‘Sad Irons’ by Robert Caro know just how revolutionary electricity was in the lives of untold millions. This, too, was denounced as a Communist plot, along with fluoride in the water.

Few will realise how stoutly the advance of Rural Electrification was resisted. The arguments against it are the old chestnuts much in use today about the evils of big government and the corruption of the flesh by easy living. Having electricity on tap would sap the vital energies of the people, and thereby lay them open to ever greater repression conveyed by radio propaganda….. Yadda, yadda, yadda said the Ann Coulters of the day.

3. The Nebraska element is the unicameral legislature that remains unique among the fifty states. Norris had seen in Lincoln and in Washington how the two houses of a legislature work and arrived at a counter intuitive conclusion. The more representative the houses, the less representative was the legislation. Already this is too hard for an ABC journalist out to demonise someone.

Invariably the two houses would pass bills that differed from each other and these two versions would have to be reconciled in a conference committee, typically of five individuals. This is standard operating procedure, and it is still is. This reconciliation goes on behind closed doors an is usually reported to the two houses in a list of items at the close of session without debate or fanfare.

Norris had seen legislation completely changed by a conference committee of five. The greater the volume of legislation, the more was delegated to conference committees, the less oversight there was applied to them.

He started a one-man campaign for a unicameral legislature and he kicked off in Hastings on Platte to reform the Nebraska state legislature by making it unicameral to squeeze out of existence this process of the conference committee. In a one-house legislature, he reasoned, all business would have to be done in the house, i.e., in public.

He upped the ante by also insisting that this unicameral be non-partisan. His proposals offended both political parties and the Hearst Press, the ‘Omaha World Herald,’ which thundered against this double-edged communist proposal: doing the public business in public! The lies and calumny was dished out Fox News fashion.

Against this mighty array of forces, Norris had two even more powerful allies: The Dust Bowl and the Great Depression.

These catastrophes convinced many that things had to change. Business as usual was inadequate to either of these challenges. In 1934 Nebraska adopted a non-partisan unicameral legislature. The monumental state capital building, only recently completed, had allowed for a second smaller, upper house which then became used for, among other things, the venue for auditioning contestants in a state-song contest. Ever practical those children of the soil are on the Great Plains.

By 1936 Norris was persona non grata in the Republican Party and he ran for re-election as an independent. Norris won then, but in 1942 lost to a real Republican, Kenneth Wherry, who is perhaps best remembered for anticipating Ann Coulter in claiming that all homosexuals were subversives and perhaps the other way around, too. Wherry is accorded all honours in the Republican Hall of Fame and Norris is absent entirely.

‘Disturber of the Peace: The Life of H. L. Mencken’ (1951 [1986]) by William Manchester

‘Voltaire in Baltimore,’ said one admirer of the iconoclastic H. L. Mencken (1880-1956).

When I moved the copy of ‘The Creed of the Sage of Baltimore’ on my office pin-board a few weeks ago to re-arrange things, I posted it on Facebook. Doing that reminded me I had read William Manchester’s biography of the Sage in 1980. Now seemed a good time re-new acquaintance with this original. Trusty Amazon not only found a copy for me, but also revealed that there had been a second edition which I quickly acquired. To call Mencken an ‘original,’ as Manchester does is right, but it hardly seems enough – unique is better. Love him or hate him or both, he was one of a kind, a singularity.

This was a journalist who carried a baseball bat down his pant leg when he went to do interviews, supposing, rightly in some cases, that his questions would provoke physical violence, and he would have to defend himself. This was a newspaper editor who kept a shotgun on his desk when receiving complaints, a near daily occurrence, from members of the public. He would listen but he would not be cowed, that was the silent testimony of the shotgun. If the complainer was cowed, so much the better.

As a boy in the streets of Baltimore, he became fascinated with the machinery in a local shop, as many boys have been fascinated by trains or trucks. The local shop was the neighbourhood weekly newspaper/newsletter. He stood for hours after school watching it. His father gave him a toy printing press and was thus born ‘H. L. Mencken’ when he printed his own business cards with it. He had always gone by the name ‘Harry’ but all the ‘r’ letters in the set had been broken in his first experiments with it, so he styled himself ‘H. L.’ and it stuck.

When he left high school he applied for a job with the ‘Baltimore Herald’ and by persistence made a go of it. He loved the life and went at it like there was no tomorrow. This was a pace he continued for the rest of his life. But the newspaper’s readership fell in a very competitive market, and the desperate editor turned him loose. He was transformed from a journalist reporting events, to a columnist dishing out opinions. Is there nothing sacred? ‘No,’ was his reply.

Sanctimonious clergymen were target practice for his daily column. When they protested in a mass delegation to the newspaper’s owner, Mencken consulted his public and private files. The public files he had collected for sometime, recording incidents of clerical misdeeds with altar-boys, collection boxes, choirgirls, prostitutes, loan sharks, gamblers, you name it. These he recounted with unequaled enthusiasm. Still the clerics protested, so Mencken went to the private files.

Mencken in his prime,

Mencken in his prime,

When he was but a reporter going where he was sent, doing what he told, he was a police reporter, and he was a very sociable drinker with police officers all over Baltimore. They provided him with still more dirt on churchmen that had not yet reached the public record. What a motherlode of gossip and libel did he find, and he did use it, having first mastered the libel laws! The clergy beat retreat, and having won, Mencken did not pursue them. There was still bigger game to hunt in the jungle of the sanctimonious.

Now blooded, he turned to the Baltimore political machine whose Mayor aspired to the spoils of a national office. Once again he published juicy extracts from the public record, connecting the dots, then he turned to the selfsame police officers for more dirt, which was supplied. But even that did not seem enough for so elephantine a target, so Mencken advertised in his column for citizens, in the strictest confidence, to confide in him information about the mayor. They did. Even he was surprised by the rapacious venality thus revealed, but this was a man for Augean stables. He treated it like a baseball game and created a scorecard, with day by day results in the race to the pennant.

His heritage was German, like many others in Baltimore, and he was proud of it. He loved German music and played the piano well on musical evenings with, first, the family, and then drinking buddies. When the Great War started, he saw it as Germany civilising Europe, and if Belgium, France, England got in the way, tough luck! His daily columns, whatever the subject matter, included an encomium to the Kaiser, Germany, mythical Germania, Bach, Nietzsche, or something else explicitly German. As the war went on and American neutrality leaned to Britain, he kept at it. While many Americans of German extraction admired his audacity, they kept their heads down.

His editor hoping to edify and distract him, sent him to Europe to cover the war. Europe? The editor gave him a steamship ticket to Southhampton and train ticket to London. The train ticket was never used. He changed ships at Southhampton for Oslo and then Copenhagen, and then bought his own train ticket to Berlin. Thence he proceeded to file dispatches from the Russian front, extolling German civility, cuisine, beer, courtesy, efficiency, etc. The editor cut off his funds and Mencken returned unrepentant. But seeing the war fervour back home, thereafter he had the wit to keep his own head down, but he never forgave Woodrow Wilson.

Then he turned his talents to editing a literary magazine. He it is that created the house style guide. His was the first to offer this service to contributors. Likewise he also was the first editor to declare what kind of stories he would publish as a guide to authors submitting. Finally, he vowed to treat authors with consideration and courtesy which was not the norm then or now. Submissions were reviewed and returned within 48 hours, and the letters of rejection or acceptance were hammered out on his typewriter. Those rejected got comments on the strong and weak points of the submission sometimes coupled with suggestions of other publications to try, and those accepted were bathed in flattery before he indicated just how little he could pay contributors. Having himself been rejected by editors with curt form letters rather like the disdainful treatment meted out by Qantas cabin staff when I used to fly with that carrier, he was trying to do unto other authors as he wished other editors to do unto to him.

In time he published stories by James Joyce, Sherwood Anderson, Scott Fitzgerald, Willa Cather, Theodore Dreiser, Edmund Wilson, Ernest Hemingway, Sinclair Lewis, Eugene O’Neill (plays in this case) and still more, when no one else would. He also pushed a young Alfred Knopf into publishing.

Perhaps his most lasting personal contribution was ‘The American Language’ which he prepared while staying his pen during the Great War. He was in part inspired to defend Americanese against the British, and their American sycophants, and so it was in part his private war against England in support of Germany. The other inspiration was the black slang he heard in the streets, the saloon talk of polyglot Baltimore, and frontier language of the west which he mostly knew through the works of one of his most beloved writers, Mark Twain. He likened Americanese to a new species of animal, living by its own rules in a new environment, quickly growing away from its origins (Britain). This was a hobby project but when it was published it obtained instant commercial and critical success, though he offended the self-appointed guardians of the King’s English stationed in the United States, and a war of words about words ensued.

HL doing what he did best, editing,

HL doing what he did best, editing,

These guardians should have known better than to take on this master of polemic, venom, and invective. The more so because he had researched the material for many years before assembling it. Ergo, he had it down pat, and he shoved it down the throats of the guardians who assailed him. In time this grew to be a three-volume work, as he tinkered with it for the rest of his life.

The Scopes Monkey trial is well known, and he was the conductor of the orchestra there. He recruited Clarence Darrow for the defence and blackmailed his paper into paying Darrow’s considerable fee.

He fought Prohibition in every way, from brewing his own beer to the pages of the newspapers far and wide and insulted, mocked every dry clergyman, condemned whole swaths of the nation for supporting such idiocy and just would not shut up. This fight gave him an even greater national profile, since many intellectuals, with secure private supplies from bootleggers, did not fight the good fight on this one.

More battles followed. One of his magazines was ‘Banned in Boston’ as was much else at the time, and he let it go, but when the Bostonians started bragging about caging the Beast of Baltimore, what was a man to do, but fight back? He went to Boston Common and sold copies of the offending magazine himself where he was arrested. At the police station he regaled his incarcerators with stories from his days as the police roundsman in Baltimore, while his lawyer did the heavy lifting. The scorecard read: Mencken 1 – Boston Banners – 0. The judge, who had been handpicked by the Banners, found for Mencken, free speech and all that.

When the good citizens of a Maryland Eastern Shore town lynched a negro, dragged from a hospital bed, Mencken fired his heaviest artillery. These great men proved everything he had ever thought about the scum of the earth. Did he go hard! Wallop! When commercial and physical threats against the newspaper and his person rolled in, he redoubled his invective. Crosses were dutifully burned. Dead animals left on his doorstep. All the tricks that are still in the Tea Party playbook were used. Nothing stopped him. He just kept at it until the villains went on to other, softer targets. Remember what I said earlier about the baseball bat and the shotgun.

Alas, Manchester includes none of Mencken nonpareil coverage of presidential nominating conventions and elections. He loved the circus, and democracy offered the biggest and best one for free. He was present at the hung convention in 1924 and must have had a lot to say about that. By the time he covered his last presidential convention in 1948, he was a bigger celebrity than most of the candidates. Journalist crowded around to interview him, while hapless candidates milled around the auditorium talking to each other.

He was an iconoclast who attacked hot air, bunkum, lies, pomposity, pretention, vain-glory, stupidity, ignorance at every turn, and if one attack was good three or four were better. Indeed, his modus operandi became so well known that one well-meaning friend asked him if there was anything he did believe in, and the result was the Sage’s creed.

Manchester offers no summing up of Mencken’s life, legacy, or impact. My own is this. Puncturing balloons is great fun, and there are plenty of hot air balloons around to puncture, and most of them have so little self-knowledge that they do not know that they are full of hot air. In this, as in so much else though, one has to know when to quit, and Mencken did not. He was like a Groucho Marx who just keeps rabbiting on ridiculing all about him, and with age Mencken became far less discerning in the targets he selected. Neither the Great Depression nor the rise of Adolf Hitler could he take seriously and so his star waned. Just as William Jennings Bryan clung to old verities, in his age so did Mencken.

William Manchester

William Manchester

Moreover, Mencken was not wholly negative. He loved baseball his whole life and never said a bad word about it, not even during the Black Sox scandal. He had a blind eye there. Manchester barely mentions the sport but one reason Mencken went to New York City as often as he did was to see Yankee games.

When I visited Baltimore for a conference, I spent far too much time conferring, and did not make it to the Mencken Room, which is only grudgingly open now and again. Likewise I did not do an Edgar Alan Poe homage such was my professional fervour, long since outgrown. I did make it to an Orioles game though! I did go over the submarine in the harbour, and I did see Fort McHenry from the water with a boatload of sozzled conferees.

The second-hand copy Amazon produced is marked up, doing the same myself with most books I read, I sometimes wonder about the marker. Is this someone I would get along with? I try to see some pattern in the mark-up. The marks in this book seem to be analysis of Manchester’s style, his choice of voice — third person past, the mix of description and anecdote, the passive versus active voice. I wonder if the writer was an author. The copperplate penmanship suggests a woman but I have been fooled on that before.

Speaking of marked up texts, as an undergraduate, I had developed a method for selecting used textbooks that worked perfectly.

First I only looked at copies that were highlighted in yellow. Why? Read on and be enlightened. Second I concentrated on those yellow highlighted copies that were densely marked in the opening chapters. Yes, there is a method to this. And remember I was buying in a crowded bookstore with many other students getting books for the semester, so there was physical and social pressure to get on with it.

Ah, the method? I discovered by the end of the freshman year texts that were marked in yellow were used by dolts more interested in the yellow marker than any meaning the text might impart. The yellow highlighter was a novelty in those days and only a few students used them, and they used them, it seemed, more as a status symbol than anything else. Why do I say that? Because the highlighting stopped within a chapter or two. Either the reader dropped the course, give up to failure, or relied on copying the work of others. Law One was: A text highlighted in yellow was likely to be clean after a few chapters.

As a corollary to this law, I also noticed that the more densely marked the first chapter was, the sooner the marking stopped. Someone who highlighted every line on page one, had no idea what was important and what was not. Such an indiscriminate marker was destined, know it or not, to drop even sooner than the average Yellow-Head, as I called them to myself. Law Two was: the more frequent the yellow in Chapter One the sooner the highlighting would stop, leaving the remainder of the text untouched.

A few times a friend expressed surprise to see me pick a book that was heavily marked in the opening pages, but I gave a spurious reason, about that marking saving me the work of doing it myself, rather than reveal the two laws above! These I kept to myself until now.

Mencken’s Creed for those too lazy to look it up for themselves. It is sometimes edited to suit the quoter.

I believe that religion, generally speaking, has been a curse to mankind – that its modest and greatly overestimated services on the ethical side have been more than overcome by the damage it has done to clear and honest thinking.

I believe that no discovery of fact, however trivial, can be wholly useless to the race, and that no trumpeting of falsehood, however virtuous in intent, can be anything but vicious.

I believe that all government is evil, in that all government must necessarily make war upon liberty and the democratic form is as bad as any of the other forms.

I believe that the evidence for immortality is no better than the evidence of witches, and deserves no more respect.

I believe in the complete freedom of thought and speech alike for the humblest man and the mightiest, and in the utmost freedom of conduct that is consistent with living in organized society.

I believe in the capacity of man to conquer his world, and to find out what it is made of, and how it is run.

I believe in the reality of progress.

I – But the whole thing, after all, may be put very simply. I believe that it is better to tell the truth than to lie. I believe that it is better to be free than to be a slave. And I believe that it is better to know than be ignorant.

‘Jeremy Bentham on Spanish America’ (1980) by Miriam Williford

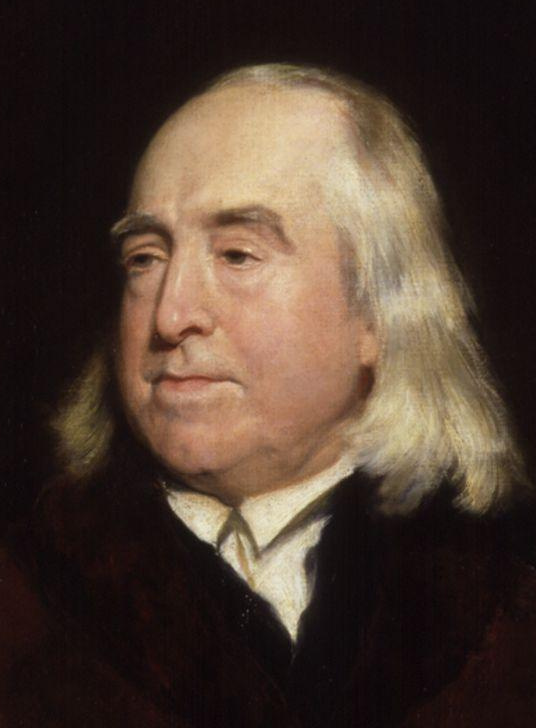

Reading about John Stuart Mill brought to mind Mr Utilitarianism Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), and I remembered that I had acquired a copy of this book years ago as relevant to utopia, though many might suggest one criterion of utopia would be the absence of insufferable bores like JB, as he referred to himself. While not a biography, the book does convey much of Bentham’s personality and habits.

The subtitle explains the remit of the monograph, ‘An Account of his Letters and Proposals for the New World.’

JB proselytised far and wide in England. He started out in law but when his parents’ deaths left him well off he became a full-time know-it-all. He wrote one tract after another, many are legal in orientation, and sent them off to one and all to influence opinion and incite action. He eschewed running for parliament on the ground that the duties thereof would distract from his broader and deeper influence. He ranged over many subject and topics, ignorance being no bar. Altogether a public intellectual!

Then he hit on the idea of the panopticon and devoted himself nearly exclusively to that for years, and sunk a lot of his own money into it. It started out as a model prison but as he honed the idea it became a more general social model. It is all in the name ‘pan’ = ‘all’ and ‘opticon’ = ‘seeing.’ All-seeing, a building made of glass so that everyone could see what each person is doing at all times. Little Brothers and Sisters are always watching! The social discipline born of this exposure would put us all on our best behaviour all the time. Michel Foucault has some things to say about this that are worth reading.

Disaffected by the failure of the Great British to embrace his panopticon, JB turned his gaze to the wider world, and there he saw Spanish America. This was a greenfield site in his mind. New societies were aborning there, and if they started off on the right foot, they would grow into perfect little Benthamic societies. He would be only too glad to tell them about that right foot.

God’s gift to humanity, Jeremy Bentham

God’s gift to humanity, Jeremy Bentham

Cue, another prodigious letter-writing campaign, and more tracts. Since he paid for the publication of his tracts they were not edited, and seldom reviewed. That may explain why most of them are so excruciating bad. Neither self-criticism nor second-thoughts featured in his personality. His contemporaries can be grateful that for every tract published he wrote two others that had to await posthumous publication in his collected works now safely confined to research library shelves for the terms of their natural lives.

The circumstances were a bit tricky, as reality can be. While Spain still claimed and asserted suzerainty over Spanish America, and these claims and assertions were largely respected by European powers, the Spanish Americans were rebelling against rule from Spain, imposed locally by appointees whose main goal was to enrich themselves with the least possible effort. San Martín, Símon Bolívar, and others were in revolt. These niceties did not bother JB, he wrote to Madrid, to Spanish colonial governors, and to the rebels offering his services as a lawgiver. Solon, reborn! Have laws, will travel.

In doing so he promoted his own considerable expertise as evinced by his numerous tracts, which he usually enclosed with his letters, and he cited testimonials from heads of states (who had never heard of him), savants (who regarded him as a crackpot), and religious leaders (who rejected him as an atheist).

Never one to stand on ceremony, while he was wooing the Madrid government to let him dictate to its restive colonies, he managed to find time to offer 400 pages of criticisms of the Madrid government, its constitution, its acts…. What a pompous prat, one might think.

More seriously, he suggested that his complete ignorance of local circumstances, and existing manners and morēs (or knowledge of Spanish) ideally suited him for the job, leaving him dispassionate, detached, unfettered, and rational. In short, he claims some of the qualities that Plato ascribed to Philosopher-Kings, though he never cites Plato, or anyone else for that matter. It is JB all the way, unalloyed.

He did make plans to travel to Mexico at one time, and then at another Venezuela but neither eventuated. Nonetheless, he continued his barrage of letters and tracts.

Imagine now a besieged Spanish governor in Peru with insurgents at the door, nearly all communication to the interior cut by Indians, receiving a letter…from Bentham running to 25 pages about whether the legal code should be written in italics or not. Bentham often seized on such trivial details and spent pages and pages on them, while the castle burned down. He had neither practical sense nor political nous. Though, surprisingly enough, some of his correspondents did take him seriously like Símon Bolívar, giving me cause to doubt SB’s wisdom. (Maybe I should read a biography of SB.)

Williford charts all this deadpan, resisting all but a few asides on the evident megalomania. This is an excellent, short monograph that shows a considerable volume of research, effectively marshalled to say what needs to be said with little fuss. Perhaps it started as PhD but if so the published version escaped the PhD-to-book syndrome – overkill.

I could not find a picture of the author.

I confess that I have a marked up copy of Bentham’s ‘Fragment on Government’ which I had to read in a graduate seminar, and I cannot remember one thing about it, except the relief at never having to look at it again.

In pursuit of John Stuart Mill I have also recently read Eric Stokes, ‘The English Utilitarians and India’ (1989) which I chose not to review, finding it so densely detailed that only a specialist in British colonialism in India could fathom it. I certainly could not, though I found informative the distinctions Stokes made among the Whig, Liberal, and Utilitarian approach to India. For the Whigs government itself is the enemy. For the Liberals education solves all problems when mixed with time. For Utilitarians there is no substitute for telling people what to do, how to do it, when to do it, and, if time permits, why to do it.

By the way, when Bentham’s parents’ estate was divided between the two sons, his brother took his half of the dosh and moved to the south of France to pursue the life of a sybarite. Who can say which was the greater service to later generations?

‘Something Bitter on the Princes’ Islands’ (2008) by Lawrence Goodman

‘An Istanbul Mystery’ says the subtitle, the fourth in a series, but the only one readily available to me.

A nice set-up with the young girl exploring the island while the dog takes charge. There is a mystery in a cave and an array of characters, Cousin Evangeline and Uncle Orville added to the mayhem. The séance was a laugh. The running joke about the talking dog was deft. The plaintiff ney lessons were part of the local color.

It is amusing, and the children are fun, and the final denouement surprised me.

On the other hand the French diplomat was not even cardboard, and after he was inflicted upon the reader, he was then dropped. Likewise the two French police officers, who were portrayed more kindly, were introduced and then dropped.

Laurence Goodman, from the back cover

Laurence Goodman, from the back cover

Having said that, I am not motivated to seek out the other titles in the series.

‘Departures’ (2008)

Thanks to the miracle of SBS Television we went to Japan last night and got back in time to go to bed, watching ‘Departures,’ a life-affirming film with cello music about death. Slow, meticulous, and accessible with some travelogue, the story of young Daigo Kobayashi’s transition from mediocre cello player to encoffiner is related, and the effects of the move on those around him, starting with his loyal, but taxed wife.

‘Encoffiner’ is one word Noah Webster did not get. In this case it means laying out of dead person to be placed into a coffin. This is a task performed before the undertaker disposes of the body. ‘Task,’ no, not the right word. Ritual is the word, a performance before the deceased’s family. It is done with the decorum, grace, and precision of the best of Japanese culture, but achieving that takes time and practice, and sometimes the difficulty is compounded by the emotions which the death has unleashed in the family. All of this, and more, is carefully documented as Daigo, reluctantly, enters this world.

He is broke, in debt far beyond Mika’s, his wife, wildest guess: celli are expensive. The ready money NK Agents offers is too tempting to refuse.

His initial revulsion at both the physical and social aspect of the work is gradually overcome when he realises slowly that the ceremony is of great solace to many families. In time he finds solace of his own in the task. Though it does take a longtime to close the loops and there is more repetition than I liked. Robert Ebert reviewed it in 2009 and gave it four stars out of four and wrote his usual perceptive comments with some comparisons to other films.

Yojiro Takita, the director with the Oscar for best Foreign Picture.

Yojiro Takita, the director with the Oscar for best Foreign Picture.

We could have watched Computer Generated Images slug it out on 7MATE but we preferred something about life and people, not comic strip nonsense made by prepubescent boys for prepubescent boys, or is that the other way around. Or we could have been hectored by an ABC journalist firmly brandishing one end, usually the wrong end, of a stick. So many choices.

I record a selection of SBS free-to-air movies based on David Stratton’s comments in ‘TV Week.’ I use his comments and not his ratings, which I find too high, though he has recently changed the method and I am still trying to gauge his new approach of categorising rather than numbering.

‘Mittsommernachtstango’ (2013)

This is a feature film from Finland, the land of low-key but often very interesting and accessible movies.

Genre? Mockumentary, I guess. It is told deadpan. A Finn writes to a tango club in Buenos Aires, claiming that the tango originated in Finland, and supplies a long and detailed history of its evolution in the far north of the far north. While the Argentines laugh it off, it is, well, curious, and what, after all, is Finland like that these people would make such a stupid claim.

Three of them club together — a guitar player, a singer, and a dancer — to head north to the land of midnight sun, endless forests that all look alike, wrong turns, language barriers, a dead battery, and reindeer on the road.

They find something they never found in Buenos Aires, peace-and-quiet, and also people who have plenty of time for them to get past that language barrier and they learn some things about themselves, Finland, and even the tango, as they finally admit. The explanation of why Finnish men like the tango is perfect.

Completely unpretentious, no plot twists, plenty of travelogue, first in Buenos Aires and then Lapland. That deity of film criticism Roger Ebert would certainly give it all thumbs up, and so do I.

Fiction? Well not quite. See Wikipedia for an entry on the Finnish tango, and be enlightened.

I read a charming review of this Finnish film about a year ago, and determined to have a look at it. I tried to get it on iTunes but failed. It could not be sold into the Australian market. I even tried to fool iTunes by logging in while in the States to no avail. Though it was available for purchase, I could not purchase it. Frustrating. Yet another chance to develop my patience. (Yes, I know about VPN, but my needs are few.)

I thought that by June 2015 it would surely be available. I was assuming it would be screened at the Sydney Film Festival, since it seemed perfect for that, and then have a commercial release and we could see it on the wide screen. I checked with a Film Festivalian of my acquaintance, who said no, it was not on the program. Rats!

I tried again to locate it for purchase and lo and behold I found a vendor and ordered it toute suite! It promptly arrived and we gave it a spin.

‘The Tin Flute’ (1945) by Gabrielle Roy (1909-1983).

A novel of life among destitute Canadiens in Montréal of the Great Depression. Yet a book that brims with life, and ends with optimism.

The description of the snow driven before the wind as a dancer pursued by a cracking whip was marvellous, graphic, exciting, and accurate. Then there was the house party and the young and inexperienced Florentine measures herself against her rivals, parents, and beau. Her combination of defensive quips and throbbing hormones is certainly right. Emanuel’s unwilling love for Florentine and her gradual response, each with inner doubts, provides the unity of the story.

Gabrielle Roy is the novelist of a Montréal now gone, the Montréal of Maurice Duplessis, and even the egregious Jean Drapeau, long before Le révolution tranquil. The working class French of 1940 stay of their side of Rue St Laurence in a quietude that is born with a stubborn resignation. The Church offers spiritual comfort in a world where there are few material comforts after a decade of the Great Depression.

That endurance is personified in Rose-Anna Lacasse, the mother of a starving clan of ten, soon to be eleven, children with her earnest but eight-year unemployed husband Azarius. All of them go to bed hungry and get up hungry. The children dress in rags and share shoes. Yet they all persevere.

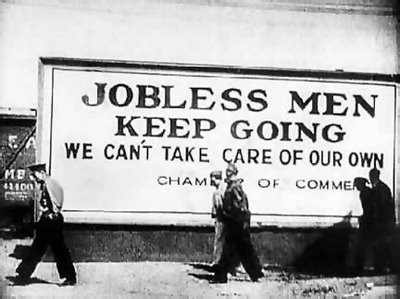

A sign in Montréal in 1939.

A sign in Montréal in 1939.

Roy enters into the lives of her characters, or maybe it is the other way around, they have entered into her life and she chronicles their determination, dignity, forbearance, and humiliations in a world they did not make, but in which theirs is to make the best of if that they can. The inner monologues of her cast of characters are compelling. Confused, determined, troubled, hesitant, defeated, defiant they may be inside, but outside each tries to maintain a façade. Rose-Anna is calm; Azarius is cheerful; Emanuel is self-contained; Florentine is scornful….

To a politically-minded person they are victims of an oppressive social order that could be changed. To Roy they are God’s children, each one precious, individual, and whole just as they are.

The novel, written by a Manitoba school teacher, provides a companion piece to The Canadian novel, ‘The Two Solitudes’ written at nearly the same time by a Nova Scotia school teacher. But the books differ. McLennan’s ‘Two Solitudes’ implies a political agenda and it looks to a changed and perhaps better future. Roy accepts eternal reality as the mystery of life in which we must trust in God and ourselves. That might sound passé, even retrograde, to some but in her hands it is a message of salvation.

By the way, in McLennan’s novel conscription into the Canadian army is feared by Canadiens, but in Roy’s novel three of the central Québecois characters voluntarily enlist, and a fourth throws himself into a war industry. The army represents a job, an income, after nearly a decade without either. (Yes, I know some of them ended their lives at Dièppe in 1942.)

Moreover, when I compare this book to so many contemporary prize-wining novels that I try, and fail, to read, I realise she has the one essential of a novelist, that so many published novelists lack, a story to tell about people. To which she adds a sympathy, an empathy for others that transcends the facile judgements that reviewers love.

I have read her ‘Alexandre Chenevert’ (1951) and ‘Where Nests the Waterhen’ (1955) and found much pleasure and occasion to reflect in each. There is a very informative biography of her on the Canadian Dictionary of Biography online web site. She wrote constantly and kept every word she wrote including letters sent (and received). The Amazon Canada web site has shown her for more than a year as ‘Roy Gabrielle,’ despite many complaints, mine among them. The Mechanical Turk has fallen asleep, it seems. I see in this mixup the fate of those with two first names, but others find a darker purpose to capture her work for the masculine!

Gabrielle Roy

Gabrielle Roy

The original title was ‘Bonheur d’occasion’ which is an idiom meaning, at its most basic, ‘Best wishes.’ The title ‘The Tin Flute’ refers to one incident in the novel. It was filmed in 1983, turning this compassionate study of grace under pressure into melodramatic drivel suitable for a mid-day movie.

‘Oscar Underwood: A Political Biography’ (1980) by Evans Johnson

Oscar Underwood (1862-1929) was contemporary and sometime rival of Woodrow Wilson, William Jennings Bryan, and Eugene Debs.

Born in Alabama during the Civil War, Underwood’s childhood was during Reconstruction when the South was occupied and pillaged to pay reparations for the war. In particular the Republican Party descended on the South to insure it would never cause trouble again by manipulating laws and voters. This baleful episode was ending when Underwood came of age, but its legacy continued (e.g., in those Confederate flags on state capitol domes).

Patrician by birth, he was a man of his time and place. He thought women should be pregnant or in the kitchen or both. Negroes were beasts of burden best kept under strict control. Southern Europeans were failed human beings. Organised labor was anathema. In his political career, to be described shortly, he was parochial, only what was good for Alabama was important.

Why read about such an obscure figure? I am glad you asked that question, Mr. Spock! (1) He was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in the famous hung convention of 1924 and (2) he was one of the ‘Profiles in Courage’ (1957) television series for his confrontation with the Ku Klux Klan. The little I knew of these events made them seem odd for an Alabaman of his time and place. (3) Having just read about the egregious Alabaman George Wallace, I wondered about his fellow Alabaman. Now is the time to find out more.

Underwood ran for Congress and represented the Ninth District (Birmingham) just as the Republican ascendancy was ending. He joined with many others to purge electoral rolls of blacks and to keep them off thereafter. He developed a lock on the Democratic Party nomination as the Republican Party died in the South.

He toadied up to the Speaker of House of Representative Champ Clark who had presidential ambitions. Clark rewarded him with the chair of the House Ways and Means Committee. At the time this was a minor post, but Underwood made it into an important one with some creative thinking, hard work, and unfailingly politeness. Underwood became indispensable to the business of the House. He was ever present, always ready to do what needed to be done, even if strictly speaking someone else was supposed to do it, no job too big, no job too small. He also proved to be adroit in stroking the many egos that needed to be stroked.

His main interest in Washington was tariffs affecting his constituency, and he laboured over the tariff schedules as though they were holy writ. He had always loved facts and figures and this subject played to that strength of this born accountant. The tariff was a major national issue and he became the master of the detail of tariff schedules, the impact of item #116 on Schedule B in Part 1.21 paragraph 2.0 on his constituency, and he soon schooled others in this detail, too, as it applied to their own constituencies.

The Ways and Means Committee, then as now, manages the business of the House of Representatives, and Underwood used this as an instrument to impose party discipline. In fact, in hindsight it seems that he had more success in securing party discipline than at any other time in the history of the House. Only when there was a two-thirds majority vote from Democrats in the Party Room, would he bring a matter to the floor of the House for a vote, but then he expected 100% compliance from Democrats on the floor of the House. Dissenters soon found strange delays in office cleaning, faulty telephone lines, etc. Nothing terribly subtle about it but then there was nothing personal in it either.

In time he grew bored. Holding the Birmingham seat was foreordained; he had party discipline to a fine art. He now contracted that virus so common in Washington, Potomac Fever. He became to think of himself as a statesman, and became a little less parochial, and he began to think another Southerner might one day soon be elected president. That Southern might as well be Oscar Underwood as anyone else. He was right, it was time for a Southerner: Woodrow Wilson.

In the 1912 Democratic Convention Underwood was one of the nominees, positioned to be a compromise candidate if the front runners, Clark and Wilson failed. Wilson prevailed, and he sounded Underwood out for the Vice-Presidential nomination, but Underwood declined. I am not at all sure how serious that sounding was, because even the naif Wilson must have realised two sons of the South on the Democratic ticket would be one too many.

Wilson’s victory was a Democrat landslide and the House majority became gigantic. Underwood used all the tactics, techniques, and tricks he had learned to discipline the mob of newbies that entered the House, each determined to right all wrongs, and change everything for the better. By that time he was an old hand at managing such upstarts. They soon discovered just how unimportant a Congressman is when there is a 100-vote majority. The object lessons were quick and decisive. Outspokenly independent Democrats had no office space, no secretarial assistance, the postage franking certificate was lost…. His handshake was firm, his smile warm, his determination to lead was Birmingham steel.

While Underwood personally had no time for the amateur newcomer Wilson, he sailed with the wind in Wilson’s canvas. And besides Wilson was far preferable to Bryan, in part because Underwood must have supposed he could manipulate Wilson, though the author is silent on that possibility. Wilson’s preoccupations with the high road and his absolute belief in the separation of powers meant that he left Underwood to run the House, and run it he did.

The first item of business was the tariff, and in the new Congress no hotel vouchers were issued, no office-space was assigned and no committee posts allocated, until the tariff schedules Underwood had devised over the preceding years had been passed. He really did hold them to ransom. Pass my tariff bill (it was an omnibus bill with 57 parts to make it harder to be amended, split, or qualified with riders) or else a new Congressman may never have had an office to sit in let alone a committee seat to brag about back home. Likewise he managed the floor debate with an iron hand. Debate was permitted but not one word off the topic was tolerated, nor were any extensions of time to debate granted. A speaker who wandered off topic would be handed a note from Underwood asking him to yield.

While the small Republican minority squawked, many of them enjoyed the spectacle of new Democratic Congressmen learning the Washington game the hard way. If Underwood’s touch seems heavy, it was light compared to that applied by the previous Republican rule when debate was often not allowed.

Underwood was both a social conservative and also a fiscal conservative, yet he steered Wilson’s progressive legislation through the House of Representatives. Politics makes strange bedfellows they say.

Like many other Southerners, to Underwood the Federal government was the enemy, and he constantly voted against appropriations for any and everything, unless the money was to be spent in Birmingham. He was one of the majority who voted to cut defence spending, public health spending, education spending, funding for scientific research, staffing for foreign missions, and so on and on. The only Federal dollars he voted to spend were those bound for northern Alabama. When, however, Potomac Fever gripped him he did try to broaden his outlook, though his heart was not in it.

With Wilson in the White House, and the House proving ever harder to control, Underwood decided to move up. He secured the Democratic nomination for an Alabama Senate seat. He fought off a challenger in the Democratic primary and easily won the election. The challenge was based on what was the central issue of national politics for some years — prohibition.

After twenty years in the House of Representatives with many accolades, Underwood entered the Senate as the newest of the new boys, and found an altogether different atmosphere. The Senate was a club whose members indulged each other. There was no urgency. Underwood who had insisted on party unity and discipline in the House became himself a dissident voice in the Senate, often speaking against Democratic measures, though at the end of the day he usually voted for them, a ploy that remains common today. Speak one-way and vote the other in the effort to please both camps. Thereafter he would often then vote against the appropriation of funds for measures he had earlier voted for. Another ploy that is time-honoured.

However Underwood did not enjoy the pleasures of the iconoclast for long and soon began managing bills in the Senate and by the beginning of his second term, he was Democrat leader in the Senate. The foreign crises with Mexico and Germany did not interest him much but he went through the motions that his ambitions required. He supported Wilson in the Great War (making sure plenty of contracts went to Birmingham) and then the Treaty of Versailles but without conspicuous energy or wit.

He had been nominated for the Presidential place in the 1912 Democratic Party convention which Wilson won. Had Wilson stepped aside in 1916, and there were such rumours, he would certainly have tried for it. In 1920, well the time was not right. He was up for re-election to the Senate and Alabama state law prohibited anyone from being a candidate for two offices in the same election. He preferred to secure six more years in Washington by contesting the Senate primary and election with an eye on 1924. He campaigned for the Democratic Cox-Roosevelt (F. D.) ticket nationally though it was a lost cause from the start.

At last we come to the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan was rooted in the South and had been rejuvenated by, of all things, the prohibition movement. It was violently prohibitionist, as it was violently racist, violently anti-Catholic, xenophobic, anti-union, misogynist, anti-intellectual…..

Underwood position on prohibition was local-option. Let each community decide for itself. That satisfied neither the Wets nor the Drys. Though Underwood was flexible and pragmatic on most issues that did not effect the material well-being of his constituents, he did stick on a few, and prohibition was one of those.

Strange right there. Alabama was prohibition heartland, leaving aside home-brew, and the Klan had been founded there. (I thought about including some Klan pictures, and there are plenty to be had, but they were all so vile, I did not.)

Perhaps it was his patrician outlook or the insulation of so many years in Washington D.C. that made him insensitive to this populist cause, but he would brook no compromise on this issue, though his entire legislative career was based on knowing the time to compromise. Moreover, when he launched his bid for the Democratic nomination he went to Texas, where the official headquarters of the Klan was located, to do it, and denounced the Klan in a speech in Houston: ‘It was a secret society that took the law into its own hands.’ The battle began. There were two other leading candidates, William McAdoo and Al Smith. McAdoo was ultra-Dry and Smith, as he used to say, was all-Wet. The Klan supported McAdoo and reviled the Catholic Smith as Satan with smile.

Again Underwood’s strategy was to be the compromise candidate if McAdoo and Smith stymied each other. He did not make the Klan the sole issue but he did repeat it many times in speeches in the north-east, mid-west, and the south. The 1924 nominating convention was in New York City and the Klan timed its national conclave to coincide with it across the river in New Jersey to show its force. Underwood introduced an explicitly anti-Klan plank into the Democratic platform, which was defeated. The gloves were off. The convention was marked by fistfights in the hall, clashes of marchers for and against the Klan in the streets, arrests of delegates, a spectacle that H. L Mencken adored. Underwood’s confrontation with the Klan, won him support from the north and west but eroded his southern homeland. This convention lasted three weeks and went to 102 ballots! As the wits said, ‘We have to make a decision, or move to a cheaper hotel!’ The nominee was John Davis….

That was high-tide for Underwood who returned to the Senate, and quickly lost interest in most things. His health had never been good, and now aged sixty-seven it got worse. He retired and spent the time dictating memoirs.

Apart from the strategic reasons of gaining a national profile in his confrontation with the Klan, I cannot understand from these pages why he did it. If it was a national profile he wanted, there were plenty of other issues to pursue that would have been less risky to his southern base, e.g., the tariff, railways, immigration, taxation, and so on.

In a fine concluding chapter the author sums up Underwood as a man of moderate ability who mastered the arcane rules of the House of Representatives and then the Senate in succession and led both, the first man to do that since Henry Clay, and the last one to do it. The author gives Underwood no moral credit for his conflict with the Klan, interpreting it purely as an electoral strategy, but that just seems too simple to this reader. If anything, it effectively made it impossible for him to be the compromise candidate between McAdoo and Smith, since it assured vehement opposition from the Drys, with and without hoods. If that was the aim, it was misguided from the start, this from a man who always counted the votes twice before they were cast. To get the necessary two-thirds of votes to win, Underwood would had to have some of McAdoo’s votes, and they should have been available to him as McAdoo was also a Southerner from neighbouring Georgia. The author does do a calculation that shows if Underwood had kept his Southern base of Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Arkansas, and South Carolina he would have had a chance.

The book is an account of his political career, much of it paraphrased from the Congressional Record. [Cue, sound of dust settling.] In some passages we get a day-by-day account of the Underwood’s committee hearings, floor speeches, and roll call votes. It was a PhD dissertation and it shows in the mind-numbing and pointless detail. None of this reveals the inner man.

I could not find a picture of the author.

I learned virtually nothing about Underwood’s childhood and how that might have shaped him for later life, like the legacy of the Civil War on this child or his boyhood experiences with blacks.

Oscar Underwood was not related to the New Jersey Underwoods who made typewriters. Nor is he related to Frank Underwood. [Get it?]

‘A reformer of the world’

Reading Nicholas Capaldi’s biography of John Stuart Mill put me in mind of Mill’s ‘Autobiography’ and I found I had it on Audible already, so the rest was easy, well not quite. See below for some comments on using the Audible app.

Although his voice was a clarion for social equality and personal responsibility, generations of students have since been taught to despise John Stuart Mill as a progenitor of evil liberalism.

Sounds odd I know, but since the 1960s jaded intellectuals have made careers biting the hand – liberalism – that feeds them, having insufficient imagination to do anything creative themselves. When these pygmies are long gone, John Stuart Mill’s books will still be read; that will be the judgement of history. It is little wonder that the feeding hand has gradually lost enthusiasm for subsidising intellectuals.

Mill started to write the ‘Autobiography’ when he had a nervous breakdown early in life and then went back to it later. In addition, Harriet Taylor had a hand in editing it. Many PhDs have been earned trying to figure out when Mill wrote portions of it, and what Taylor took out or put in. The Audible version I listened spared me this Pin-HeadeD detail.

The early chapters are a description of the childhood of this prodigy with an emphasis on his father’s method of educating him. It is exhausting to listen to the account, the more so knowing, as he must surely have himself known in retrospect, that most of it was meaningless. Prodigious, yes, but neither lasting or meaningful. He may have read in Greek Plato’s ‘Apology’ at five years of age, but he did not understand it. So, too, with much else in this force-fed education, which was all work and no play everyday for years on end.

James Mill

James Mill

One unintended consequence of this gruelling education was that Mill was THE hyper-nerd. He grew up in a hot house that he seldom left until he was a late teenager when he went out of the house to go to work at the East India Company where he toiled for his father.

East India House

East India House

He was in his father’s shadow for much of his life everyday, socially, intellectually, and morally. It is painfully apparent to an auditor of the ‘Autobiography’ that Mill had no friends. He had peers; he had colleagues; he had associates; he had debaters and opponents. But he had no friends, which he as much as says more than once, though he uses the term ‘friend,’ it usually means someone he knew, and nothing more intimate. He had no interests but the unforgiving logical analysis of important matters learned from and constantly reinforced by his father. This is not the person to sit next to at dinner. He could debate the great issues of the day but he could not make small talk, or show any interest in pictures of a seat-mate’s children. A cold fish, I would guess. Ready to beat you to death in argument and inept in passing the butter, because he never played any boyhood games meant he had zero physical dexterity, something he himself notes twice in the ‘Autobiography.’

Chapter Five (5) is superb. In it Mill reflects on his many and varied experiences, and knocks off some bon mots as only he could. He paraphrases Thomas Hobbes’s remark that ‘When reason is against a man, he retaliates by being against reason’ which made me think of all those deniers (climate change, Catholic Church pedophilia, Holocaust, Greek debt, etc.). I listened to this while walking the dog, pushing pedals at the gym, or taking the train, so I could not take notes or mark-up the text.

HIs conclusion in this chapter is that political theory is best confined to a few principles which would allow inferences to be drawn in particular circumstances, rather than trying to lay down a single ideal institutions. Mill lost faith in a singularly unified theory and recognised the inescapable influence of context. Under the influence of Alexis de Tocqueville, Mill wanted the deductions to be based on facts, hence I referred above to inferences and not deductions.

Likewise, Mill concluded that perfect political institutions were of no value in themselves. The underlying social order was decisive. The most perfect political institutions would be hollow shells unless the society valued and embraced them for their purposes. To make a comparison, the church may be full, but do they really believe and act like Christians everyday in every way?

Mill once fancied himself ‘a reformer of the world,’ but during his depression, he asked himself this question: If all the material and moral ideals he espoused were realised in the world, would he then be happy? No, he answered. He concluded that happiness if not an end in itself, but rather a by-product of purposeful activity. Both trip and arrival are important.

In Chapter Six (6) Mill refers to Mr. Warren and the villages he set up. It was a passing reference but I want to see it in the printed text when the copy I ordered arrives. I found a reference to Warren and his villages in a history of anarchism. Mill’s praise for Warren villages is odd, since Mill knew nothing about them, not even if they existed. So much for Tocqueville’s influence.

Later in Chapter Seven (7) he refers to the Hare-Clarke voting system as the salvation of representative government over several pages. I have passed these passages on to Anthony Green. Likewise there is also in this chapter a reference to multiple votes for the educated, rather than the propertied, and I must get that and send it to Glyn Davis who once asked me about my comment, somewhere, on Mill and multiple votes. In the ‘Autobiography’ Mill says he proposed multiple votes in a submission; I have since tracked it down and will pass it on in due course.

There are some odd things about the ‘Autobiography’ to be sure. Mill never mentions his mother though there are many, many references to his father who died when Mill was thirty (30). It would seem his father had those nine (9) children all by himself. James Mill was a formidable fellow but he was no hermaphrodite. While there are only a few early references to Mill’s work for the East India Company. Yet Mill specialists have some strange stories about his habits at work.

This review affords an opportunity to correct some errors I made in the review of Capaldi’s biography. It was not Bentham that introduced Mill to poetry. Several peers led him to poetry. I also said he was called a Mechanical Man, not quite, but rather a Manufactured Man by some who found the analytical engine of his mind artificial and inhuman.

I found this Audible reading to be unsympathetic. It sounded almost mechanical, phrases of equal length and inflection followed one another without regard to the content. Perhaps that is partly a fault of Mill’s writing style, which is replete with dependent, relative, and embedded clauses with asides and comparisons which makes it precise but it does not flow.

Not quite easy I said, because Audible kept dropping out, asking me to log in again, resetting the book mark, and so on. None of that is easy when using the iPhone while dog walking. No doubt I brought this on myself, somehow. But it was annoying, and a lesser man might have quit.