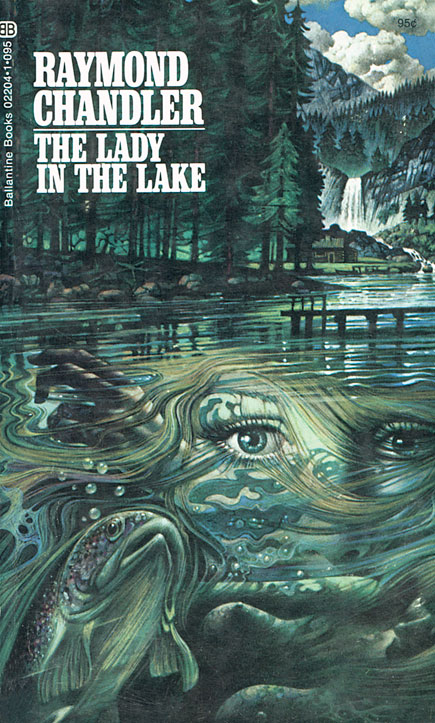

I came across Jacques Barzun’s ‘Catalogue of Crime’ (1989) and spent several evenings flipping through it, reading the 50-100 word reviews, each a model of composition, trenchant, clear, and definitive. I searched for reviews praising unfamiliar writers to broaden my horizons, but also came across golden oldies like Raymond Chandler. Of Chandler’s ‘The Lady in the Lake,’ Barzun wrote…..

‘The exposition of the situation and character is done with remarkable pace and skill, even for Chandler. This superb tale moves through a maze of puzzles and disclosures to its perfect conclusion. Marlowe makes a greater use of physical clues and ratiocination in this exploit than in any other. It is Chandler’s masterpiece.’

High praise indeed, the more so considering the source. If you don’t know Jack, it is time you did. Try Wikipedia for a start.

After reading the ‘Black-Eyed Blonde,’ reviewed elsewhere on this blog, I recalled this praise and decided to re-new acquaintance with it. I tried to find it as an audio book while travelling, but that did not work out, and that, too, is explained in another post. When I got back to the Ack-Comedy, while shelving the 18 kilograms of travel reading I came across the very book: ‘The Lady in the Lake’ in a 1971 printing from Canada which I must have purchased for .95 cents in graduate school penury. The back cover is long gone and the front cover is torn, but all the pages are still there with all the words.

Wow! What a trip. What an arrival. I was pretty sure I remembered the plot, and who done it, but even so there were twists and turns that surprised me. In fact, at one point toward the end I began to doubt my recollection. It did not seem to be developing as I remembered…. But then it did, after another turn and twist or two.

And what a cast of characters: Almore, the needle doctor; the icy Miss Fromsett; laconic Jim Patton who saves Marlowe’s bacon; Lavary, the oily lady’s man one time too many; huffing and puffing Kingsley; and Lieutenant Degarmo, who, in the end, was a cop; demoralized Captain Webber; malevolent Mildred; the hollowed out Graysons; the illusive Mrs Fallbrook; Bill Chess, the crippled war veteran; and more.

The strength of this title is that cast of characters. As in a Frank Capra movie, all the supporting actors are given their due. Each gets camera time; none is reduced to plot device, not even the very dim Bay City patrolmen. No two sound alike. The voices are all distinct. Although there are descriptive passages, they are largely just that without the sardonic metaphors, similes, and comparisons that Chandler could do like no one else.

I stress that ‘no two sounded alike’ because in more than one krimie an ostensibly diverse set of characters all use the same speech mannerisms, idioms, and syntax. When this happens the characters blend and I suspect that the author is unaware that these are distinctive mannerisms, idioms, and syntax. I refrain from mentioning the names of offenders. It is on par with those very tired clichės about ‘climbing’ into bed. The last bed I climbed into was a upper bunk bed on a sleepover as a child. No bed since then has needed climbing either into or out of. Yes, this is another pet peeve.

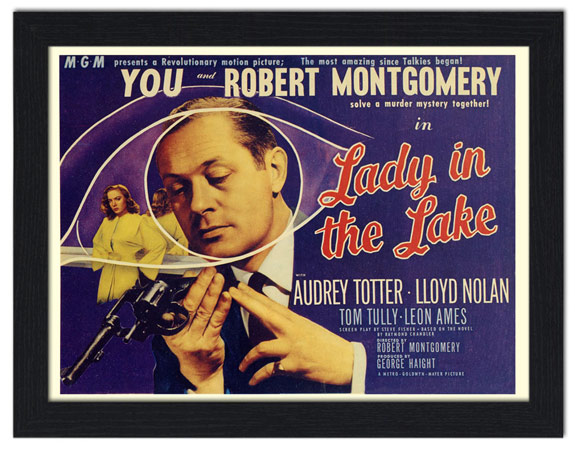

There is a 1947 film, starring Robert Montgomery as Marlowe. It takes far too many liberties with the novel, but evidently with Chandler’s approval.

There is a 1947 film, starring Robert Montgomery as Marlowe. It takes far too many liberties with the novel, but evidently with Chandler’s approval.

Back to the ‘The Lady in the Lake,’ I have to admit that there were some dead spots. The most significant is the motivation of Mildred in the first murder of Mrs. Florence Almore. I never did quite get that. Moreover, it made no sense to me that Talley was there at the time to steal the shoe. But once done that set the ball rolling. There were a few passages that fell flat and some references that went over my head, e.g., ‘cheese glasses’ (p. 30), as in drinking glasses; ‘This is dum if I know whether I could or not’ (p.61); ‘those moustaches that get stuck under your fingernail’ (p. 187); and, the decor was ‘ashes of roses’ (p. 192). What colour is that? Cheese glasses? A moustache under a fingernail? Dum? You lost me, Ray.

Author: Michael W Jackson

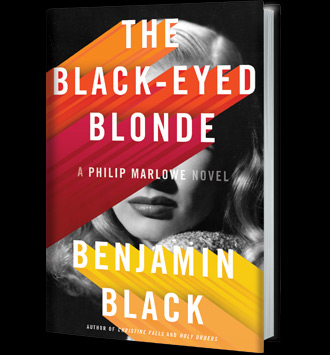

Benjamin Black, ‘The Black-eyed Blonde’ (2014)

Good Reads meta-data is 304 pages, rated 3.51 by 3,483 litizens.

Genre: Krimi: Species: Sunshine Noir.

Verdict: Brilliant, in a word. * * * * More, please!

Never thought I would say that a Chandler imitator bettered the master, but here it is. This is Philip Marlowe in the California sunshine of 1947 and he is in top form! This novel might as well be a lost manuscript of Chandler’s come to light, such a ring of the master does it have.

Every page crackles with sharp asides, deadpan dialogue, and show stopping imagery. Here is a sampler.

‘The telephone on the desk has the air of something that knows it is being watched.’

‘I was about to use my special deep-toned, you-can-trust-me, I’m-a-private-detective voice’ but she didn’t wait for it.

‘…there was someone else, and now I knew who it was. I’d known for some time, I suppose, but you can know something and at the same time, not know it. It’s one of the things that help us put up with our lot life…’

‘That’s a possibility I’d rather not have entertained. But once you think a thing, it stays thought.’

He had such an easy charm ‘you’d find yourself inquiring if he was all right and saying you hoped he hadn’t strained his wrist by having to keep that heavy-looking gun trained on you…’

‘The mist clung to my face like a wet scarf.’

‘My eyes felt like they had been lightly roasted in front of an open fire.’

‘I saw him walking down the street the other day and he didn’t look dead at all.’

‘I’m the hired help, but you’re talking to me like someone you’ve known all your life, or someone you’d like to know for the rest it. What gives?’

‘I stand at the window a lot contemplating the world and its ways.’

‘I don’t know your name,’ I said. ‘No you don’t…do you,’ she replied.

‘I was thinking about this and that, this being Clare Cavendish, and that being Clare Cavendish too.’

‘Of course I’d come. I would have gone to her if she had been calling from the dark side of the moon.’ [Amen!]

In context, each of these passages hits the mark! Marlowe smokes too much, drinks too much, pays too little attention to money, and hangs on like a bulldog. It just does not add up, so he keeps going until it does, add up.

The ride includes a coshing or two, a pistol whipping, rape, torture, four murders, and a suicide. Though most of the mayhem occurs off camera, Midsomer’s got nothing on this body count.

The femme fatale is very femme and very fatale, spy beautiful, as Chandler wrote of another of her kind. But also, at times, blushing and shy. Marlowe has a hard time squaring that circle. At the end, so does the reader.

Her mother steals the show at one point, she a self-made woman in the perfume business and mother of this Aphrodite is not at all what Marlowe expected when summoned. No airs, no graces, no manners, and no nonsense!

Though Marlowe is unaccountably slow witted about finding the missing man’s sister. In fact she finds him. He asked doormen, gardeners, and drivers about the missing man but not the sister. Go figure. Maybe it is a ploy; play hard to get she’ll come to you.

The gimlet was a give away to the cognoscenti.

Benjamin Black (John Banville)

Benjamin Black (John Banville)

Not at all sure why anything would be called Liberace in 1947. The man took that name in 1950 and was by no means well known at the time. The casual reference to a Rolex watch jarred in 1947, long before it became a status symbol for the idle rich. Marlowe is surprisingly incurious about the femme fatale’s brother. Ditto a reference to Air Canada flying direct LA to Toronto, Wikipedia says Trans-Canada Airlines took the name Air Canada only in 1965. That part was easy to check. More than 2,000 miles for a 1947 aircraft. OK the date is not specified.

By the way that title has been used before with a different meaning.

L.R. Wright, ‘The Suspect’ (1985)

A Canadian krimie from the Sunshine coast of British Columbia on the eastern shore of the Strait of Georgia and just northwest of Vancouver, though populous and favoured by tourists, it can only be reached by ferry. Ergo it is somewhat remote.

Because of the mild climate, it is also favoured by retirees. In this story two brothers-in-law figure, both in their 80s. After a lifetime of putting up with each other, one kills the other. Ah, all those family Thanksgivings and Christmases are enough to drive anyone to extremes. Though here the palette is darker still. The deed is done.

The perpetrator prepares to face the police, but when the Mounties come to get their man, they ignore this frail old man in favour of suspicious types who may have been seen around. That is a nice set up. Once he has been passed over, the perpetrator decides to let it be. He does not blurt out the confession he had rehearsed but goes coy and vague. That of course, in time, makes the Mountie, Karl Alberg, who sticks with the case, suspicious.

Alberg finds the time to romance the local librarian, Cassandra, but neither of them seems very good at romance. The villain is a library user and their paths cross.

Along the way we find out more about the Mountie, who never wears the uniform, and the librarian, and Gibsons, the town. There is much gardening, I suppose because it rains so much there, as in Rain City, Vancouver.

I am not whether this is part of series. Nothing is said on the cover.

L. R. Wright

L. R. Wright

L.R. Wright has a number of titles, and perhaps I will try another.

Julian Barnes, ‘The Porcupine’ (1992)

The novel offers an account post-Communist show trial in the heart of darkest Eastern Europe told as a test of wills between the defendant, the 35-year dictator, and the prosecutor, a professor of law, who got the assignment because no one else wanted it; too many skeletons in that closest. They spar in interviews and also in the courtroom.

During the tumult of the Change, when the Red regime fell, most records were destroyed and few records were kept in the first place. Should evidence of the dictator’s undoubted crimes be fabricated, or will the new regime settle for convictions for pilfering office supplies? Enter Fox News which I am sure could puff up a few office supplies to an unprecedented national disgrace with its distinctive combination of hysteria and ignorance.

I gave the game away when I referred to this as a ‘show trial’ for while the new regime wants to break with the past, needs must. The prosecutor has a crisis of conscience. True believers remain and perhaps the old regime will return.

The deposed tyrant is no fool and he gives as good as he gets in his confrontations both in interviews and in court. A decisive result is necessary.

It all becomes didactic. Argument and counter argument, and not much recognisable human feeling in any of it. There is a kind of utopian element in the ambition to create society anew, to build a new and better society, but it is not developed in this short book.

Julian Barnes

Julian Barnes

I read It in 1993 but retained no memory and when I happened to see it on the shelf I tossed it in the pile to take to Hastings in 2015.

Raymond Chandler, ‘The Killer in the Rain’ an Audible Book read by Elliot Gould.

While travelling I went looking for Chandler’s ‘The Lady in the Lake’ on Audible to test Jacques Barzun contention that it is the best of Chandler’s many good novels, but all I could find was a cut down dramatised version. I did listen to that and it had the essence of the plot but not enough of the prose. I also noticed ‘The Killer in the Rain’ and took it, too. This was a reading not an enactment.

‘The Killer in the Rain’ is a collection of early short stories by Chandler which, in this version, includes:

‘Killer in the Rain’

‘Goldfish’

‘Finger Man’

‘The Curtain’

Having read the complete Chandler oeuvre, I have read these stories but have not thought of them for years. Time to re-new our acquaintance.

Two things emerged. First, I heard characters, incidents, events, situations that Chandler re-worked later in his novels. It was interesting to realise that good as the stories were, they were improved when he re-worked them into the novels. Though there also people and events in the stories that did not make it to the novels, some pretty arresting ones, especially those goldfish and the small woman with the big gun.

Second, Elliot Gould was all wrong for this assignment. He just does not sound like California. He lacks the laconic sunshine in his voice of, say, Dick Powell, Robert Montgomery, James Garner, or Powers Boothe, all of whom have had a turn at Marlowe. Yes, I know Humphrey Bogart was also a New Yorker but he did not sound it the way Gould does. Now perhaps it is because I know who Gould is that I say that. But while I am saying it I will add that he sounds like a New Yorker.

His diction is perfect; he does well in distinguishing the voices of all the characters, yet I quibble.

There is more, perhaps I was also distracted because I know why he got the assignment. He played Marlow in a Robert Altman film ‘The Long Goodbye’ in 1973 derived from Chandler’s novel of the same name. And that is my point, because that film was a parody of Marlowe. Its expressed purpose was to show how inept and unsuited such a figure as Marlowe was in the real word of crime and corruption.

To return to my theme. Gould’s claim to the job is that he was the anti-Marlowe. That niggled me, too. That made two strikes against it. I cringed at his New York voice and I just knew he had no sympathy for the character he was projecting. Had he any sympathy he would never have done the Altman film!

There are dozens of alternatives to listen to on my iPhone but I stuck out ‘The Killer in the Rain’ to the end. Why? Chandler’s prose.

Raymond Chandler

Raymond Chandler

That man could turn a phrase, spin a metaphor, bite off a line, all in the warm California sunshine he could present a very dark, very black world.

The bad news is that Gould is the reader for most of the Chandler titles on Audible.

I discovered Audible Books with my first smartphone, a Samsung, and liked the idea. At that time I walked the honourable dog several mornings a week and sometimes in the afternoon, too. Kate and I were both working and we took turns. When on dog walking duty I listened to talking books.

I was familiar with talking books on CDs and had listened to many on drives in the States, including much Marcel Proust. Those titles were all books that had been produced for voice. With Audible I also discovered books that were only Voice Books, just as there are books that are only Electronic books, v-books and e-books. The first v-book I heard was a freebie from Audible, that must have been the business model to lure in customers, about letters to Sherlock Holmes’s address. It was a nice idea for a set up. I joined Audible and continue to subscribe.

‘King’ (2013) by Allan Levine

When he retired William Lyon Mackenzie King held the record for the longest serving prime minister in the English-speaking world, exceeding the record then held by Robert Walpole, in all 21 years. To put that in perspective, note that Australia’s Robert Menzies had 18 years and Franklin Roosevelt 13, and Churchill 11. In addition, King was the leader of the Liberal Party for a total of 28 years. I expect he still does hold the record for longest serving party leader, too.

William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King

Roosevelt had a charm even over the radio and daring ideas, Churchill could wake the dead with his rhetoric and was willing to try almost anything, while Menzies exuded confidence and calm. King had none of these assets. He was short, round, and pudgy. He had no love for meet-and-greets. He spoke in a high squeaky voice that sounded worse on radio than in person though it sounded bad then. He invariably read his speeches word-for-word badly. He had no electoral coattails to make backbenchers beholden to him.

Then why did he succeed? The short answer was said in an obituary ‘He divided us least.’

The legends of King are many, and most have to do with inaction: he never let his left hand know what his left hand was doing, he never did by halves what could be done by quarters and he never did at all what did not have to be done. Like a duck holding place against a tide, he paddled furiously below the surface while doing nothing up top. That image is from Churchill in another context but it fits King perfectly.

It is said that he had all cabinet ministers sign undated letters of resignation as a condition of being named to cabinet and that he kept those in his pocket in parliament during debates or question time occasionally bringing one or all out onto the desk as though about to date a resignation and by this means stimulating his colleagues to fervour. This book does not mention this last story and rather emphasises the care he generally took in stroking the egos of those around him in his earlier years, but it is also clear that he changed over the years, and grew ever more determined to hang on. Still he had plenty of wiles, like calling an election in the speech from the throne! Students of parliamentary procedure will realise how startling that would be.

In his youth, before the concept existed, he became an experienced and successful labor-management mediator in some pretty difficult circumstances. His approach was to get the parties talking, sometimes about trivial things, like where to meet, the shape of the table, and the like, to get them into direct dialogue about something, anything concrete. All the while he would present the factual context and try to get them to agree to the description of the situation. In this effort he was deferential, polite, patient, and had an iron butt to see the job out no matter what.

He was headhunted into politics when a PhD student in economics at Harvard. He entered parliament and became Canada’s first minister of labor in one swoop. His mentor was Wilfred Laurier of the $5 bill made famous in tribute to Mr Spock in 2015.

In office he championed social welfare measures but never tried to push ahead, always waiting for the community to accept such measures as child bonuses, pensions, and so on. His touch in these judgements was sure though there is no telling how or why he had it, since he seldom left Ottawa and when he did, he avoided voters as much as possible. In the few campaign rallies where he spoke he entered by a backdoor, read his leaden speech, and left. With experience he became a more accomplished speaker but never in the same league as his contemporaries, Churchill and Roosevelt. Canadians could hear both the latter often, and King did not try to compete with them.

His reluctance to push ahead irritated many who urged prompt action to use the votes he had in parliament, but King never hurried. Never. The votes in parliament were necessary but what was sufficient was the mood of the country, and divided Canada has many moods, all at once. For example, to some child bonuses were paying Catholic Québécois to procreate.

Divisions! Plenty of those. The prairie provinces are alienated from Ottawa. Not to be outdone the left coast of British Columbia is even more alienated. The impoverished Atlantic provinces are home to the forgotten people. Prince Edward Island cannot be found on some maps of Canada. Quebec is a world unto itself outside Montréal. Labrador and the Northwest Territory are on the dark side of the moon. Ontario owns most of the country. Federal elections were won and lost in the Ottawa River valley, i.e., Ontario and Quebec.

King became leader when he was the rising man, and also at a time when the Liberals seemed certain to lose and none of the other likely candidates wanted the job. He got it, and he kept it.

Many winners are born lucky in their opponents, and King certainly was. The Conservatives found one way after another to alienate vast sections of the electorate, usually by preferring Ontario’s interest to the exclusion of the rest of the country, and making no effort in Quebec which was ceded to the Liberals. In effect, the Liberals were the only national party (sound familiar?) in Canada for much of this period, getting votes and seats in every part of the country. There were elections in the only Conservative seats were from Ontario with a very light sprinkling from nearby Manitoba.

Having observed Laurier, King determined to keep Quebec Liberal at all costs. He did this by finding a loyal lieutenant, first Ernest Lapoint and then Laurier St. Laurent (who later succeeded him as leader and prime minister), to concentrate on Quebec. King pretty much gave them a free hand. He seldom went there, spoke no French, and viewed Catholicism with suspicion.

Over the years there many remarkable events, among the most outstanding were these.

First, the Bynge Affair. As the incumbent prime minister he was at loggerheads with the Governor-General after an election produced no majority. The Liberals lost a substantial number of seats and the Conservatives won many new seats but neither had a majority. The convention would have been that King resign and step back and let the Conservatives form a government, but he hung on for weeks and argued the point with Governor-General Bynge ad nauseum. He finally did resign and the Conservatives tried and failed and a new election followed where King secured a thin majority. Why he protracted the matter is hard to fathom and the author can only say that he was a selfish man, hardly a satisfactory explanation, since King was smart enough to know what he was doing, but what was he doing? King had predicted that the Conservatives would fail, indeed he told that to the Governor-General as a reason why he should stay in office, but he would not back his judgement until pinned to the wall.

Second, King advocated a Canadian foreign and defence policy so did not agree to accept all British decisions or recommendations. Unlike Australia’s Robert Menzies, he did not participate in the Empire War Cabinet in World War II. Instead he said Canadian decisions will be made in Canada by Canadians in the interest of Canada, spending very little time in London, again unlike Menzies. This line outraged the Canadian Britophils, especially in British Columbia which has long lived up to the first part of its name, but it soothed Québécois. It did not satisfy anyone but it did not completely alienate anyone either.

Third, though he advocated unemployment relief in principle, when the Great Depression hit he was unprepared for the magnitude, and he did not warm to John Maynard Keynes’s approach to government budget deficits. Moreover, he was rude and crude publicly in his reaction to protests. No man of the people was he. Moreover, he refused to let the federal government cooperate with the provincial governments held by Conservatives, a sorry example of vindictiveness replacing compassion. Not one dollar to those provinces which hath sinned against Mackenzie King! He lost the next election and found opposition dead boring, leaving the running to others. In a way this loss was lucky for King and for the Liberals because it left the Conservatives in office in the teeth of the Great Depression, and so left them to carry the opprobrium for not combatting it.

Four, there is no doubt his crucible was World War II and conscription. In World War I Canada had poured men into the Western Front, and had taken a perverse pride in the lists of dead. The drain on manpower was incredible, and Laurier slowly and reluctantly accepted conscription. While English Canada was ready for it, Quebec was not.

A brief aside, Québécois speak French but have no love for France. Like the Boers of South Africa who speak a Dutch, they feel they were abandoned by their country of origin, traded away at a conference table. At times Québécois think of themselves as Normans abandoned by Parisiennes.

Laurier legislated conscription in 1917 before the USA entered the war and it led to riots in Montrėal and produced few Québécois soldiers but much ill will. King wanted no repeat of that. His line, which pleased neither the zealots for Britain, nor the Québécois was no conscription unless necessary and conscription only if necessary. It had no ring to it. But if it did not please either camp, neither did it fatally alienate either camp.

In 1944 the Canadian army wanted men to replace its battle losses, including 2,000 at Dieppe which is barely mentioned in this book. But after the middle of 1944 the outcome of the war was inevitable and King would not budge, despite the pressures brought to bear from generals, Liberal backbenchers and ministers, the press, the opposition, and the British and American allies, he held firm. One argument for more troops was that a greater commitment would give Canada a larger role in the peace that followed, say at the United Nations. King had no interest in such aggrandisement. The price was too high. Conscription in July 1944 when the war was all but won in Europe, and Canada had little interest in the Pacific War, would have produced a rupture with Quebec, and would have jeopardised the Liberal lock on it.

While he held off those who wanted more troops he was calm up top, furiously paddling down below.

Five, in the post-war period when a Soviet defector revealed a spy ring in Ottawa, King smothered it, at least compared to the way similar revelations in the United States and Australia were fanned into flames. Those implicated were pursued but he did not try to exploit it with the electorate though that was urged on him by many associates. As always he preferred the minimum, not the Aristotelian mean, the absolute minimum.

In his personal habits he was notoriously frugal and recorded, in the best Scots tradition, every penny he spent. This personal frugality carried over into a reluctance to spend government money. Even for cherished projects like unemployment relief in the Depression.

He never married though many women were courted in his early life, none quite made the grade. There is no mistaking his loneliness in his mature and later years, though our author is insensitive to it. That he was a bachelor was an oddity, for then as now, the norm is that the democratic leader to be a normal, married man, façade though it may be. The exceptions are few and none with King’s endurance.

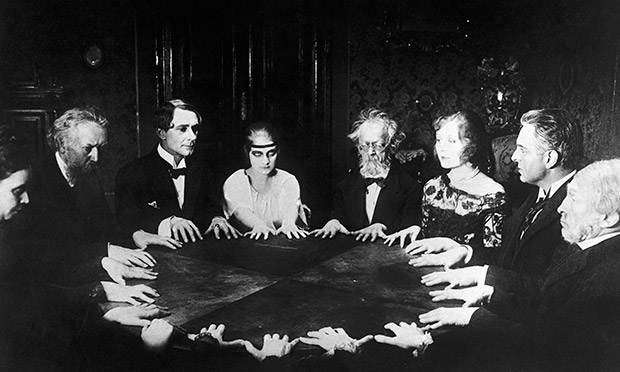

Stranger still was King’s life long obsession with spiritualism. The author has many derogatory things to say on this subject and only grudgingly notes that spiritualism had a following among many educated and intelligent people at the turn of the twentieth century. King attended sėances, consulted fortune tellers, had tea leaves read, and so on, all this meticulously recorded in a diary he kept all of his life, writing 5, 10, 15 pages a night in long hand which he had typed and filed each morning, leaving behind a houseful of boxes and binders of this diary.

Yes, Prime Minister!

Yes, Prime Minister!

He never seems to have read a book or listened to the radio for amusement or relaxation. His only relief from duty, apart from his love of dogs, was this diary. His only companion was a dog, three Irish setters, one after another.

Even more unusual is his near childlike belief in an enchanted world where a cloud formation foretold events, or a draft that blew a paper to the floor was a sign. Everything that happens, and I mean everything, from leaf drops, to birds in the sky, they were all communications of meaning which he recorded in his diary, linking the cloud shape to his decision to appoint X to this or that post. He confided these enchantments to his diary and did not tell X he got the job because of a cloud looked like him!

King combined this spiritualism with a Christian duty to serve mankind. The book is silent on his church-going habits and how he squared what he heard in church with his spiritualism. By the way the focal, but not exclusive, point of his spiritualism was his mother, giving the pop psychologists much fun. Our author has no feel for religion in one’s life and treats it as a hobby, one that is less amusing than the spiritualism.

As he aged King became a tired old man who took out his aches and pains, and loneliness, on his staff. He worked many to the bone, and some to death, and seldom thanked any of them. There is megalomania in all that. It is always about King. When a subordinate dies at his post doing his bidding, King’s first reaction is irritation that the chap let him down.

His name needs explanation: William Lyon Mackenzie King was the maternal grandson of William Lyon Mackenzie, himself a formidable figure in Canadian history and politics. It was his mother’s father’s example that led him into public life, and it was an inspiration he acknowledged now and again over the years in stressing his sense of duty. The author has hard time playing this with a straight bat. There are enough cheap shots in this book to please Bill Bryson.

The book has had many accolades. This reader will not join the chorus. I found the writing sloppy, the organisation repetitive, the analysis of King’s political successes and accomplishments just greater than 0. Instead there much sneering at the spiritualism, again and again, meanwhile accepting events as inevitable rather than examining the dynamic that brought them about. While the author notes King’s enormous capacity for delusion, he accepts most of the factual assertions in King’s voluminous diaries, seldom seeking confirmation from another source. Contrast this approach to Robert Caro’s Herculean double-checking in his biography of Lyndon Johnson. Most of King’s delusions stemmed from the enchanted world he inhabited, which often made him seem to be central figure. If Churchill wrote him a letter about some routine matter that was conclusive proof that Churchill admired, respected, and was influenced by him.

Allan Levine

Allan Levine

Explanatory note. Above I have referred to Québécois and not French Canadians. Many French Canadians live outside Quebec and they seldom identify with it and its causes.

Helene Tursten, ‘The Fire Dancer’ (2005)

A Swedish krimie in a series featuring the insightful Inspector Irene Huss. These are police procedurals of a high order. This is the second Huss novel I have read. Evidence is compiled and interpreted, witnesses are questioned repeatedly, and finally Huss sees something in it. The locale is well realised, as are the manners and morēs of contemporary Sweden in Göteborg, along with the weather.

This story revolves around arson and spans 15 years. Huss makes several mistakes but admits it and continues. She has grit, that is for sure. The Fire Dance of the title is very nicely done and makes sense.

Huss, when not pursing murderers, copes with two teenage daughters who are fast outgrowing her influence. Her husband works as many nights as she does and that makes things difficult, despite the abundant good will of all parties. He is a chef in a restaurant.

That is the molasses, and here is the vinegar.

There are far too many distractions, most of which do not develop either plot or character. There are repeated descriptions of rooms and clothes that contribute zero to the story. Yet in contrast, Angelika, a principal character, is left practically a cartoon figure there to be stupid, vain, and just get in the way, not a human being at all, but an annoying plot device.

In reality police work on many cases at once, true, but in this novel there is a second plot that occupies a quarter of the book and contributes nothing to the main story line. Art must reflect life, yes, but it need not repeat it word-for-word.

If the superfluous description were substantially reduced and the secondary plot truncated to an aside the book would shed 100 pages, and increase the likelihood that a reader will finish it. When an author spends so much space on descriptions and the secondary plot, readers begin to think that they somehow will play into the resolution. That is the contract between krimie writers and krimie readers: If it is there, then it is relevant in the end. Not so here. This contract goes double for procedurals which this title certainly is.

Huss’s home life is well handled but there is just too much of it. The husband’s collapse seems contrived and is wholly irrelevant. Yes, I know, life is like that, but this book is not life, it is art.

Finally, I just did not get the motivation of the villain. It did not register, just voilà, he did it. Why?

I felt very early that Huss jumped to the conclusion without any evidence that the victim had been held prisoner, when, especially given how strange the victim was, she just might have gone off on her own. Of course that is what happened but it seemed like Huss had read the book and knew the future! Equally, the initial description of the victim as icy and remote does not payoff. It is there, it seems significant, it is well written, and, it is irrelevant.

‘Red House on the Niobrara’ (2013) by Alan Wilkinson

The book is a day-by-day account of six months spent in the middle of nowhere on the banks of the Niobrara River in the Sandhill country of Nebraska. Nothing happens…but life. The roof leaks, winter hangs on too long, the grass needs mowing, the grasshoppers devour the kitchen garden, shopping trips to Chadron are iffy in the old wreck he drives…. Modest, matter of fact, impossibly romantic, hyper-realistic at times, and every word a labor of love.

This book is one man’s tribute to a woman he never met, she being Mari Sandoz (1896-1966). If you do not know Mari Sandoz, perhaps now is the time to make her acquaintance.

She was a writer and her titles include: ‘Old Jules,’ ‘Cheyenne Autumn,’ ‘They were the Sioux,’ ‘The Story Catcher,’ and ‘Sandhills Sundays.’ She was a lifelong proponent of the rights of the native American Indian, long before it was a fashion for celebrities to take up photo op causes. Wilkinson aims to write a book about her.

Wilkinson’s reasoning, Mr Spock, is that to write about Sandoz he would understand her better for knowing the environs that formed her, namely the Nebraska Sandhills.

Though the book takes the form of diary entries and is very chatty, it is at the same time more formal than many books I have read. (I suppressed a comparison here on the grounds that these reviews are always positive.) By ‘formal,’ in this case, I mean careful to give a full exposition so that the reader can understand.

Alan has visited parts of the United States many times but Nebraska is it, first Willa Cather and then Mari Sandoz. He has even been to Hastings and is proud of it! This is a man who knows quality.

Much as I enjoyed reading the book I was surprised he did not mention James G Niehardt who is surely the poet laureate of the Niobrara. Or did I blink and miss it? Nor does he say anything about the Indians that so dominated Sandoz’s imagination, but some are still around there. Though he went to Chadron several times he did not go on another hour to Alliance to see Carhenge! That is hard to believe. But then Carhenge is hard to believe, but I have seen it with my own four eyes.

Wilkinson says he does not like Sandoz’s novels but I have good memories of her ‘Cheyenne Autumn’ and ‘The Story Catcher.’ Memories which for the moment I will leave undisturbed.

Alan Wilkinson

Alan Wilkinson

Donna Leon, ‘By its Cover’ (2014)

Commissario Guido Brunetti remains in top form. Age has not wearied Donna Leon. The prose is crisp, the place evoked, the people differentiated, the ear for dialogue is pitch perfect, including that all important element of many conversations — what is not said.

This adventure takes Brunetti into the world of rare books when thefts from a specialist library come to light. To understand better this strange new world he seeks advice from friends of friends and others among the many strata and castes of contemporary Venice. Though the impact of tourism is mentioned Leon does not, in this book, dwell on it, perhaps remembering that those tourist dollars keep Venice afloat on its lagoon, much more so that any support from the government in distant Rome.

Brunetti’s home life is evident but treated with a light and sure touch. Though we learn about some of his meals, the pitiless descriptions that populate some, many tiresome krimies is avoided. Likewise she seldom if ever describes clothing or even people. The exceptions to this lack of description are well judged to bring out a person’s character, not an automatic gurgitation to fill space that is so common in lesser works.

Once again, as often the case, Signorina Elettra finds out anything and everything about others, and gives nothing away about herself. Her private networks are more extensive and efficient than the police files. In addition, her hobby seems to be computer hacking. Some receptionist, she.

That is the molasses, now for a touch of vinegar. The book suffers from the Foyle Syndrome, though not so pronounced as in some of her other titles in the series. The Foyle Syndrome? It is so named for Christopher Foyle of the eponymous television series. Over the years the lazy script writers for Foyle relied on plots in which Foyle alone is virtuous, unsullied, uncompromised, the only, the last just man in a completely corrupt world. Regular as commercials on television and just as repetitive, Foyle would show in each episode that his superiors and associates were all villains themselves, along with the target villain. His superiors and associates lied, cheated, stole, blackmailed, murdered as much as the target villains. Whew!

Lacking in imagination, the writers evidently could think of no other way to emphasise Foyle than to contrast his white purity with the black hearts of ALL those around him. One day, no doubt the writers will turn on Sam, his loyal driver, and reveal…. Well, something bad.

I stopped watching Foyle, as I do not find saints quite as interesting to watch as the scriptwriters find it easy to write them. Foyle’s sermons at the end were just too much. Agatha Christie novels are much more subtle than this.

There is a touch of this syndrome in all of Leon’s books, but it does not distract here. Comments on the general greed, corruption, and incompetence of Italy and Italians are matter of fact, like comments on the weather. The proximate embodiments of all that are his superior Patta and Patta’s attack dog, Lieutenant Scarpa. These two are ciphers at best, more plot devices to inject some tension into the proceedings.

Donna Leon

Donna Leon

‘Casablanca’ (1942)

Reading about Vichy France reminded me of this film, so I watched it again.

Love the film, but not the many historical inaccuracies in it, though it is easy to forgive them, still we should not forget them. Here are a few.

1.There were Germans in Morocco to monitor the neutrality of the Vichy Administration, but none were permitted to wear uniforms.

2.The Germans dressed in mufti and were confined to poor hotels in Rabat, not Casablanca.

3.The Germans were permitted out and about only when escorted by many French soldiers, almost as though they were prisoners. Had they travelled to Casablanca, they would have had a large French military escort.

4.The French governor of Morocco in Rabat, General Auguste Noguès, had in 1940 advocated continuing the war from North Africa, and he made as many difficulties as possible for the Germans in Morocco, while following the letter of his orders to cooperate. There were complaints by the Germans, but the matter was too low a priority for pressure to be exerted.

5.Ergo there would have been no singing in nightclubs.

6.No questioning of travellers.

7.No truckloads of German soldiers.

8.That immutable letter of transit is wrong, too. De Gaulle’s signature would have landed the bearer in the slammer. Pėtain’s signature perhaps.

9.There was little if any unity among the anti-Nazis within a single country let alone internationally as depicted in the film. No Norwegian would not flash the cross of Lorraine to anyone let alone a Czech.

10. There was a sizeable language barrier between Norwegians, Bulgarians, Czechs, French.

The deep ambiguity of the situation is certainly true and Casablanca was perhaps, I do not know, a magnet for refuges.

Hitler’s only interest in the French Empire was to keep it and its colonial army, warships at anchor, and other military, financial, and natural resources from the Allies. Germany did not have the troops or the access to the four corners of the globe directly to do this, but if the paper-mâché regime at Vichy could effect those exclusions, it was worth the comic opera pretence that it was independent.

There is another ambiguity, too, that of the Roosevelt’s enduring effort to maintain diplomatic relations with Vichy, first when both it and the USA were neutral, and when the USA entered the war he tried hard to maintain diplomatic relations with the still neutral Vichy. Ergo there may well have been an American consul in Casablanca.

FDR also undermined de Gaulle for years, even after the invasion of North Africa, when much to the chagrin of some advisors to FDR, the French troops there responded to de Gaulle, and not the puppet they had put up instead.

These ambiguities muddle the clean lines of the story from the first shooting in front of the poster of Pėtain’s to the bottle of Vichy water at the end, but they explain how confused and confusing the situation was for those individuals.

It is unlikely that the screenwriters had this detailed knowledge. And finally, who cares! It is entertainment not a history lesson.