Swiss Made (1968)

IMDb meta-data is a runtime of 45 minutes, rated 6.7 by 35 cinematizens.

Genre: Sy Fy. Species: Contact.

DNA: Swiss.

Verdict: Satire.

Tagline: McKinsey Management Rules!

The managers manage the Brain Centre World State which has everything and everyone under control in an alpine Eden. The few dissidents who remain are confined to picturesque care centres far away. Integrated citizens have a 1968 computer chip in their brains that link them individually to THE BRAIN CENTRE (TBC). (But not to each other.)

TBC plans and regulates everything from the food each person consumes, to the colour of clothes to wear on Tuesday, to the work to do today, to sexual partners, and more. This is the paradise of Florida small government where everything is controlled…by the will of all, or at least a majority. The border is closely guarded to keep out others because the boat is full.

Should an individual face a decision – take the train or the bus, have sex with that one or this one, turn left or right, buy new shoes, pat the dog, or go to church – there is a Brain Box on every corner with direct contact to TBC. No need to take personal responsibility for anything in this Super Nanny State, just push a button and ask for instructions.

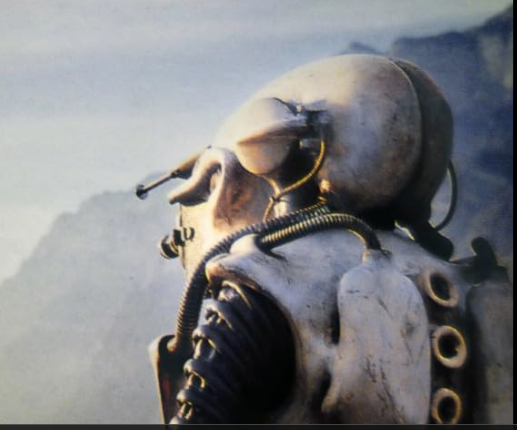

Into this world comes an alien in a life-support suit to interview people who explain to the alien’s fish-eye view the wonders of the TBC. Many do so, each with the undead monotone of a zombie as they mouth the words ‘democracy’ and ‘freedom’ without meaning, words without music. It is indeed a total state.

Fail to use a crosswalk, toss an apple core on the ground, think lustful thoughts, improperly sort the trash, and the omniscient TBC knows and files it away for your report with reprimands, corrections, and directions at the end of the week. It is worse than a private residential school or a nagging Fit-Bit wristwatch.

Citizens are advised by TBC to take soma regularly, and they do.

At the time it was a satire on the xenophobic Swiss fetish for order, but now it fits the omnivorous appetite of McKinsey management to control everything.