Harry Martinson, Aniara (1956).

Genre: Sy Fy: Species: Epic poem; subspecies: Blank verse.

Good Reads meta-data is 157 pages, rated 3.85 by 3001 citizen’s.

DNA: Sweden.

Verdict: 47.

Tagline: Helvetet är andra människor. (Hell is other people.)

The basis for an opera, and four films. Whew! Awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1974 for being the second most important book published in Swedish. Double whew! The only Nobel Prize for SyFy, apart from those in economics.

What’s the story then?

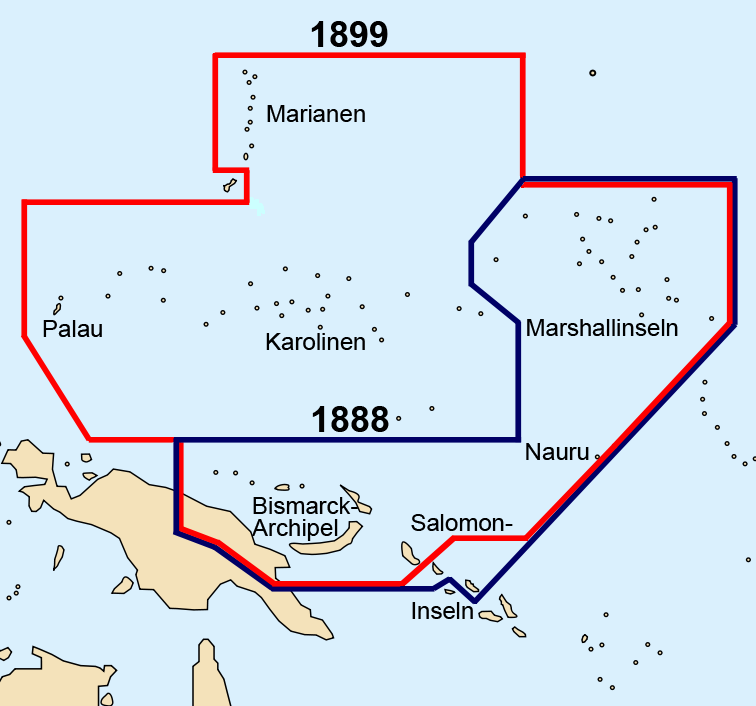

Aniara, a routine shuttle carrying 8,000 people, lifts off for Mars from a despoiled Earth. (‘I told you so,’ said Greta, again.) It is a three-week flight aboard this Volvo ferry with its casino, IKEA shopping mall, theatres, and such mod cons with 2000 rooms each with an en suite bathroom(?). Millions have taken this ride before. But hardly has this one left Earth orbit for the jaunt when the unimaginative writer’s friend, a meteor shower, strikes. The contractor who built Aniara did not anticipate such an occurrence and the ship is damaged. Like the mighty Bismarck, the Aniara’s rudder is mangled and the craft cannot be steered. Instead it is thrown well off course toward the light-centuries distant Lyra constellation.

Pippi Longstocking, Max von Sydow’s knight, Inspector Beck and other Swedish stereotypes are on board. The crew attempts repairs to no avail, and there is no emergency road service from Volvo for Aniara. These 8000 are condemned to live out their lives, as are their descendants, within this metallic shell on the way to Lyra where they will never arrive (because the ship itself will wither en route into a Marie Celeste hulk). What meaning is there in this existential crisis? See above.

(Was this the basis for StarLost in 1973. Hope not. But it is a trope in a lot of SyFy before and after 1956.)

In addition to all the other short term diversions the ferry has Mima with its minder. What is Mima? Mima is an AI as conceived in 1956. It is referred to in the same casual I might refer to my iMac, and so I can only guess what it is. Mima is there to inform, entertain, educate, and pacify passengers during the short trip to Mars. It has a repository of tapes, both video and audio, but it also receives and intercepts transmissions from the ether, including from Earth. Intended to function mostly as a diversion for three weeks at a time, when left on continuously for the years of this journey it becomes increasingly self-conscious, and it is aware of the situation. It is sentient enough to realise the hopeless situation even as it itself wears out, those flash drives and circuit boards don’t last forever, and sentient enough to feel dread of the darkness to come. The minder became the central character in the two film versions I have seen.

So for the first few months or even years Mima keeps up a happy face, but like Grock the clown it grows melancholy as it ages and becomes decrepit. The CDs wear out from repeated spins. It receives incomprehensible transmissions, perhaps from alien beings. It loses contact with dying Earth long before all that.

(Note to self: turn off iMac before it becomes sentient.)

Mima mirrors the hopes of the passengers and as this robot loses hope, so do they, or vice versa. On board the population re-enacts much of the stupidity of life on Earth. There is wasteful use of resources that are not infinite on Aniara. Salvation cults come and go. Orange demigods strut and fret. First there is unlimited orgy followed by celibacy. Human sacrifice was a short-lived fad. (Get it?) Through it all Aniara drifts on.

While we learn much of Mima’s moods, the passengers keep eating and drinking. Those supplies seem infinite for this three week crossing which has stretched to more than twenty years within a few pages.

It is partly a take on a common Cold War setting of mixed group of survivors of a nuclear war, having to deal with each other. e.g., Five (1951), Day the World Ended (1955), On the Beach (1959), This is not a Test (1962), The Earth Dies Screaming (1964) and many more. This trope has since been done to death and well past that in the Post-Apocalyptic genre that has exploded in recent times. But in this case none of the passengers are distinctive personalities.