An American Saga: Juan Trippe and his Pan Am Empire (1980) by Robert Daley.

Goodreads meta-data is 529 pages rated 4.38 by 106 litizens.

Genre: Biography +

Verdict: Chapeaux!

If ever someone was born to do business it was Juan Trippe (1899-1981) who made Pan American Airways the colossus of the sky it was for two generations. Before coming to that story first a word about the name. The Trippe family emigrated from England to Maryland in 1660 which at the time was a safe haven for Roman Catholics. He was called ‘Juan’ in honour of an aunt by marriage named ‘Juanita’ who came from Venezuela. At gatherings of the clan, she was the presiding matriarch. He was whitebread through and through, and not hispanic, though it is often implied that he was, the more so because of Pan Am’s later domination of Latin American skies when it was the semi-official flag carrier of the United States in foreign air. This misperception was cultivated at times to win favours south of the border.

As a teenager he was sky-struck, as was the likes of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in France. The lad Trippe went to an exhibition of stunt flying on Long Island (circa 1912) with his father and thereafter never had another interest. Even girls came a distant second to the siren’s song of the air. (His libido is completely absent from this telling though he did marry in 1929 and sired four children.) At Yale University he day-dreamed of flying and when the Great War loomed he was quick to volunteer, lying about his age, and choosing the US Navy because it offered recruits fast entry into its flying service. Some of the things he liked about the Navy that stayed with him included the order, hierarchy, discipline, and the uniforms. Unlike, St-Ex, Trippe was a good pilot and made full use of his training. (Sidebar: As much as St-Ex loved flying and wrote lyrically about it, he was a lousy pilot. See my earlier post about a biography on this writer and soldier.) However, the war ended and so did Trippe’s flying. He was but eighteen at the time and he set about to make a living by flying.

From the myriad of details the author has assembled several characteristics of Trippe emerge. He made mistakes, and he learned from them. He was in a hurry to get to the future, often running before he could walk. He seldom dwelt on mistakes, defeats, or failures, but quickly moved on. He saw opportunities long before others. He was an unflappable negotiator and in the longer run that was his strongest asset; he just did not quit. (In this way he calls to mind Barbara Castle.) He was unfailingly soft spoken and polite, even when being verbally assailed by angry competitors who grew frustrated at his persistence. His touch at hiring subordinates was good, and once in place he delegated a great deal of authority to them.

Zipping through the stratosphere thrilled him, but he was even more enamoured of spreadsheets and ratio of fuel costs to pounds of payload. After 1918, hundreds of other military-trained pilots liked flying and tried to make a living from it by barnstorming tours, stunt flying, circus acts, joy rides, and more, in contrast he went at it as business competing with trains and ships for freight, not fun. When he talked to someone it was about miles per gallon or turn-around time on loading. He carried a notebook which he filled it repeatedly with all he learned.

When he did fly, he spent much of the air time mapping the ground below for features a pilot might need to know from flat pastures, to rock outcrops, to nearest towns. The man had application. This is in contrast to St Ex who once airborne often seemed to pass into a reverie with the skygod and sometimes overshot the destination, had not unlocked a control, failed to make a turn, ran out of fuel against a headwind because he did not notice either the wind or the gauge.

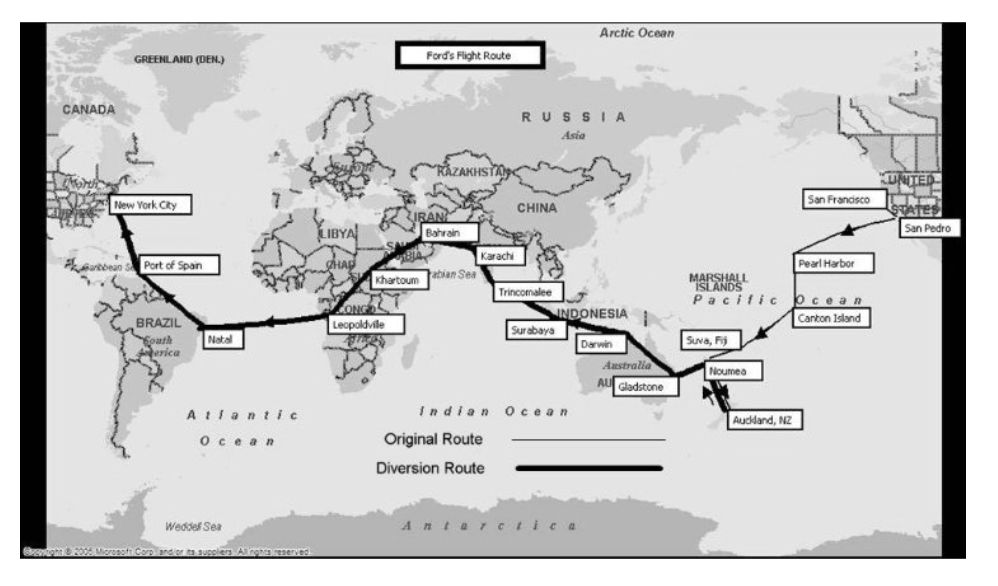

Trippe also spent much time in the New York City public library studying atlases, maps, sea charts, annals of shipping companies, meteorological texts, and more as he – long before anyone else – pictured aircraft flying passengers across the Atlantic and then the Pacific Oceans. Neither Wake nor Canton Islands showed on atlases in 1929 but Trippe found them mentioned in the handwritten logs of merchant sailors from Nineteenth Century sailing ships and US Navy archives, and in due course they became Pan Am way stations across the Pacific. (As first coal and then oil powered ships, replacing sails, these uninhabited islands had been by passed and forgotten.)

Trippe must have had moments of doubt and despair, but these did not make it into this book.

When in 1919 he bid for a US Postal Service contract and won the route from Miami to Havana (which at the time was a portal to all of the South America) he had no airplanes, no staff, no landing fields, no agreement with the Cuban authorities to land. But once he had the contract with nine months lead time, he got everything together. Almost.

He spend a lot of money preparing an airfield in Key West. When he finally went there to see for himself, well, no matter how much construction was done, the continual high water table engulfed the flat landing strip and as the deadline neared the aircraft engine exploded due to poor quality fuel. With days to go, Terpsichore paid him a visit. To hell with landing strips, to hell with wheeled aircraft, he found a battered seaplane (such as he had trained on in the Navy) and hired it to fly it and a twenty-pound bag of mail to Havana, where it landed on the water, needing no permissions. From that moment of invention came Pan Am’s clippers in the next decade.

Very soon he spent all of his time at a desk (often on the telephone) in New York City and seldom flew after age twenty-nine. For years he looked younger than he was, and at times when wooing investors hired an actor as a frontman to win their confidence in maturity.

Trippe was always worked ahead of the competition, and also his own investors as well as the boards of directors, and that often led to conflicts, some of which he lost, and walked away to continue elsewhere. There were other innovators in aviation, of course, but he often led the way with designing aircraft to carry cargo, to carry passengers, to carry cargo and passengers in pressurised cabins with meal service, ever more powerful engines, non-stop flights, with jet passenger planes, and jumbos, and so. Then there was the hierarchy of rank, the naval uniforms, and other amenities to make flying seem easy and normal and, most of all, safe. Putting women in the cabin crew was part of that psychological of safety.

He usually shunned the limelight, unlike many celebrity CEOs. When his companies, planes, or personnel made the news by establishing new firsts in civil aviation, others took the press interviews, not Trippe, who by then was knee-deep in a new project. Journalists who inquired of him were likely to be directed to someone else. The people he wanted to impress were bankers and financiers who would invest in his next dream, and they were not going to swayed by laudatory newspaper stories with clichéd headlines. The people he wanted to talk to were engineers, designers, and technicians. By the same token the entry in Wikipedia is sparse for an individual who had such large footprint.

Yet he understood the allure of celebrity and established and traded on a relationship with the most famous aviator of the day – Charles Lindberg. Lindy was awash with opportunities but what Trippe offered was more flying in ever newer airplanes over unexplored routes and this combination appealed to the adventurer Lindberg who flew airplanes conspicuously marked Pan Am where no one had done so before, boldy going. Such markings were another Trippe innovation. Where Lindy went the newsreels followed. (They came to a parting of the ways later when Lindberg became an apologist for Hitler. That is another sad story in its own right.)

Alarm bells rang at the State Department in Foggy Bottom when in the 1920s a German consortium set up an airline in Columbia. While the business was perfectly legal and operated through a local company in Bogotá, a German controlled airline in the Western Hemisphere touched the Monroe Doctrine nerve. After all, an airline had the potential to be an enemy air force in a future war, and one based close to the Panama Canal was a strategic threat of the first rank. Diplomatic pressure on Columbia was applied and that slowed development but did not stop it. In this context, Trippe was encouraged by the State Department to extend his ambitions southward, and that suited him fine. Pan Am was developing into a semi-official state airline that carried the flag even as France, Germany, and Great Britain were themselves developing state-owned airlines.

That status was compounded later by the Post Office Department, in letting contracts for foreign airmail, ruled that a single carrier was the most efficient and effective means, and not a series of competing airlines using different schedules, sites, standards, and so on. That single preferred carrier was…Pan Am. Yes, when not nailed to his desk in a two-room office in New York City, he was in Washington nearly every week lobbying with his spreadsheets and honeyed-tongue. He more of less wrote the Post Office ruling.

Later his exclusive and exclusionary business practices were challenged by rival airlines in both courts and Congress. He won those arguments on the grounds that he had an ‘achieved, natural monopoly,’ that is, a monopoly achieved by pioneering. Any rival ought not to profit from Pan Am’s investments, say, by using its facilities, data, or routes. The monopoly was not the result of shady financial practices but rather of bold innovation, risk-taking with its own money, and the pioneering efforts of its flyers.

While in each case the conclusion was close run and carefully worded, nonetheless the result was that Pan American Airways was a state airline in all but name. Yet it was not subject to direct control by the government that authorised it, unlike Imperial Airways in Great Britain which flew where and when the His Majesty’s government directed.

To be sure this status had benefits but it also had burdens. In 1940 Pan Am was pressured by the State Department into building more than twenty airports in Central and Latin America to a military standard in case a threat to the Western Hemisphere came from the Bulge of Africa. At the time it seemed possible that Germany would occupy the French colonies of Morocco and Senegal with the cooperation of the collaborationist Vichy regime, and then use the French and Dutch West Indies islands as forward basis to operate against the Panama Canal with the help of the many Germans resident in Columbia. Later Pan Am was again coerced into organising a series of way stations in Africa between Monrovia and Cairo to allow for air cargo en route to the British in Egypt. Much later its Latin American installations were integrated into the US Space program for tracking and weather reports. N. B. In all these cases it was Pan Am, not the State Department, that negotiated with the host governments. Because of that it was sometimes referred as the Air State Department.

Backing up to 1929, still not yet thirty years old, he had commissioned the first purpose-built airliner. conceiving of it as an astral equivalent of a luxury ocean liner. The nautical theme chimed in with the flying boat’s milieu, and it was systematically applied in both design and furnishings. As regular freight and then passenger service was established in the Pacific the new Boeings were called clippers to evoke the sailing ships that had plied that ocean blue.

Note on terminology. Land planes use wheels. Sea planes use pontoons which are filled with fuel. Amphibians have both. Ski planes have…skis. Catapult planes had a brief fashion but later were confined to military use. Flying boats like the clippers use the hull for landing, no pontoons. By the way, making the clippers amphibious was not possible for technical reasons mainly because of the weight, especially on take-off with a full load of fuel, but also on landing. They were beasts. To equip them with struts on the wheels and enough wheels to distribute the weight would add even more weight and degrade the aerodynamic qualities of the craft.

There are many other examples of his approach to management which would not get him an MBA from the McKinsey School. Noteworthy is his delegation of authority, disinterest in micro-management, long term view, premium on safety, patience, resilience, modesty, and more. He did anticipate McKinsey in his insistence that everything, and I mean everything, be documented for future reference. He was willing to gamble but he wanted to learn from mistakes, not repeat them. He valued these qualities in subordinates, too, and funded projects that took years to complete without a demur.

In 1939 there was a management coup d’état on Fifth Avenue in the Chrysler Building where it was now headquartered (before constructing its own building [the lobby of which I once entered]). A decade before Trippe had selected all the directors who were personal friends and some distant relations, but as the need for capital increased the Board of directors included more bankers and lawyers who owed him no loyalty. Though Pan Am was gargantuan as airlines of the time went, it was losing a lot more than money than it was making. It had more 50,000 miles of routes through 47 countries with 125 planes, 145 ground stations worked by 5000 employees around the world. The only gap in its route was between Hong Kong and Léopoldville (Belgian Congo) which was left to Britain’s Imperial Airways and France’s Aéropostale. That made it larger than the US Army Air Force at the time, let alone every other incipient airline. However, only the Latin American mail routes were regular enough to make pesos. In the vast Pacific service was irregular. Worse, crashes there were a few. Over the Atlantic Pan Am had ambition and had invested very heavily in preparation for flights but there was none in the offing. Trippe had made Pan Am and now it in its board of directors unmade him.

That interregnum lasted eight months, during which Trippe was moved sideways and a new CEO installed who liked having his picture taken, but everyone, including the new CEO, soon realised he did not know much about Pan Am and nothing about running an international business or an airline and he quit. With little fanfare Trippe, not yet forty years old, returned to the big office. During the months of exile he had attended meetings and sat silent for the whole time watching (and waiting).

There is a fascinating sidebar about China National Air (CNA) which Trippe had bought years before to provide a base in China when Pan Am finally got across the Pacific. When Japan invaded China in 1937 CNA was caught in the crossfire, and Trippe, wanting no part of this war, pulled everyone out, but some employees would not leave and tried to maintain service of a sort. Trippe thought this madness and fired them, but kept paying their life insurance policies (for their families) and kept them on the list for bonuses. Ergo he could truthfully say that Pan Am had divested itself of CNA, while allowing benefits to accrue to the wildcat airmen. That remainder was motivated by a love and respect for China and the Chinese, and in time found a protector in Madame Chiang. In the perilous years of the war in China, that airline became a lifeline flying over the Hump (look it up). Like Trippe himself, these employees also identified nearly completely with the airline they had built up and could not bear to dismember it. We might conclude that he saw something of himself in these few dedicated individuals. Later they were returned to the fold and credited with seniority for those lost years and back pay for the bonuses that had accrued. This is one of many instances where he demonstrated loyalty to employees quite foreign to the cosmology of McKinsey Management in which the cogs are interchangeable, a fact lightly disguised with a rhetorical lip service about the importance of ‘our people’ whoever they are.

By the middle of the 1940s it was clear that lobbying Congress and departments of state was a full-time job and Trippe put a woman in charge of Pan Am’s Washington D.C. office who became a Vice President of the company. She was often underestimated by politicians and officials she dealt with and proved invaluable to Trippe is sizing up one situation after another. The journalists of the day ignored her completely with the same unerring judgement so common today. She steered Pan Am through some very rocky patches and Trippe came to rely on her completely when he went to Washington.

By 1947 Trippe saw that the future of passenger aviation was the jet engine and for that to be profitable it had to take customers away from ships and trains. The way to do that was to offer speed. That meant non-stop flights to London, Rome, Paris with a hundred or more paying customers. Those who manufactured engines and built airplanes told him in great detail that it was impossible to do that, and he persisted. He often seemed not to hear these negatives and just pressed on. Finally, he gambled big on jet engines by buying them for airplanes that did not exist, and then convinced Boeing (after Martin, Douglas, and Lockheed declined) to design and build a jetliner round them, the Boeing 707. A knowledgable observer has opined that the 707 broke the tyranny of distance in Australia.

He followed his usual practice of divide and conquer with the airplane and engine manufacturers and drove hard for the development of the first Boeing 707 but soon moved on to the Boeing 747 and the jumbo jet, which still rule the skis in other forms. All of that cost millions and millions but on he drove until one day in 1968 when he quit. Yes, cold turkey. He announced his resignation at a board meeting in the evening, cleared his office the next morning. It was a thunder bolt both in Pan Am and in the business in general. He had typed all the necessary documents himself, so not even his personal, private secretary of twenty years knew until he told her the following morning.

One innovation Trip rejected, despite considerable pressure, was the SST or Concorde as it became. The US Air Force wanted a supersonic transport, and a commercial interest from Pan Am would help to stimulate development, but Trippe did not like anything about it. To reach the speeds it did it could carry only a few passengers and the noise it made would turn airports into uninhabited zones. We saw one of these beasts take to the air while we were trudging, suitcase ladened, across a rental-car parking lot at Heathrow, and it was L O U D! It also spewed black exhaust.

He became emeritus but never uttered another word beyond pleasantries in the office, in board meetings and in conferences, and he eschewed most invitations to speak here and there. In retirement he made it a point to preserve the history of Pan Am with a foundation that created, devised, maintained, and ran a corporate archive which this author mined.

As a national, flag-carrying airline in all but law, Pan American Airways was in the odd position of having no domestic routes to feed into its international flights. While Trippe’s lobbying had long allowed it to monopolise foreign travel, that very success united the domestic airlines against it and they prevailed with Civil Aviation Board in excluding Pan Am from domestic routes. One could fly from Sydney to LAX on Pan Am, as I did, and then from New York City to London on Pan Am, but not from LAX to New York. In time as other carriers muscled into the international market that monopoly disappeared, leaving Pan Am suspended in the ether with no domestic business, despite much lobbying. Ultimately that imbalance was fatal.

That was bad — worse was to come with the oil shock, and soon the empire that at its peak employed 40,000 people with more than a hundred long haul aircraft in the air every day, grudgingly conceded to be the industry leader, crumbled. With five years of his resignation, the Pan Am of old started to disintegrate, selling off assets, discharging employees at the top and bottom, all the while the new management paid executive bonuses of a magnitude Trippe had never done.

One of Pan Am’s many safety precautions was that each member of the crew had to be triple qualified. Think of a football coach’s depth chart. Each crewman had to qualify for three different jobs, for example, the radio operator was also qualified to pilot and navigate. And so on for each one. Ergo there was triple back-up on each crew. Qualification was done through third parties certified by the government. In addition, on long haul flights there were two of everything: two navigators, two co-pilots, two pilots, two radio operators, and two engineers so they could work twelve-hour shifts. Each of these ten would have two other qualifications.

We don’t find out much about Trippe the man in these pages. Was that name a burden as a boy? How did he court the woman who married him, and what kind of home-life did they have, if any. There were children but was he a father to him, taking them to air shows as his father took him? Did he have any interest beyond the company? Collect stamps? Dig in the garden? Did he always keep his libido in check? When he lobbied officials or politicians, did he start from first principles, appeals to patriotism, establish personal relations, belittle rivals, or offer incentives? He had always been secretive and solitary and those qualities increased with advancing age as he became some of a recluse in his corner office.

The book certainly does explain Pan Am’s semi-official status, but with its emphasis on the accomplishments of flight and the technical achievements to make that happen, apart from the management spill, I never did understand where the money that Trippe spent so freely came from, especially in the earlier days. Yes, there were investors, but who were they, especially through the years of the Great Depression? What kind of return did they expect or get?

Pan Am was always parsimonious in management costs. Trippe paid himself well below the industry standards for CEOs and so, too, everyone else employed by Pan Am from Vice-Presidents to cabin attendants. Some of the VPs he recruited were surprised to be taking a pay cut to join Pan Am. Ditto pilots. His unstated principal was that the experience of working at Pan Am was a bonus in itself. Certainly for those in technical fields Pan Am offered opportunities no other airline matched. For crew the allure of international travel was there. For all there was the glory and glamour of Pan Am. It seems a case of an individual who came to belief his own advertising. Still it worked as long as Trippe was there, but when he quit the looking glass broke and very soon pilots, mechanics, caterers, and cabin staff, they all went to strike for industry standard salaries. In response the new executive team dismissed personnel and sold off assets to pay for their own bonuses. Ah, the pure, sweet air of McKinsey management.

The book is based almost entirely on original sources, interspersed with newspaper accounts from the day. There is a detailed appendix explaining the research that went into the book, and it is impressive. Much of it was in interviews with the principals in the 1970s and rich as that lode is, one might worry about memory especially since few of these individuals kept diaries at the time. Nonetheless, the groundwork is assiduous and everything was double and triple checked, including a visit to Wake Island! Chapeux!

* * *

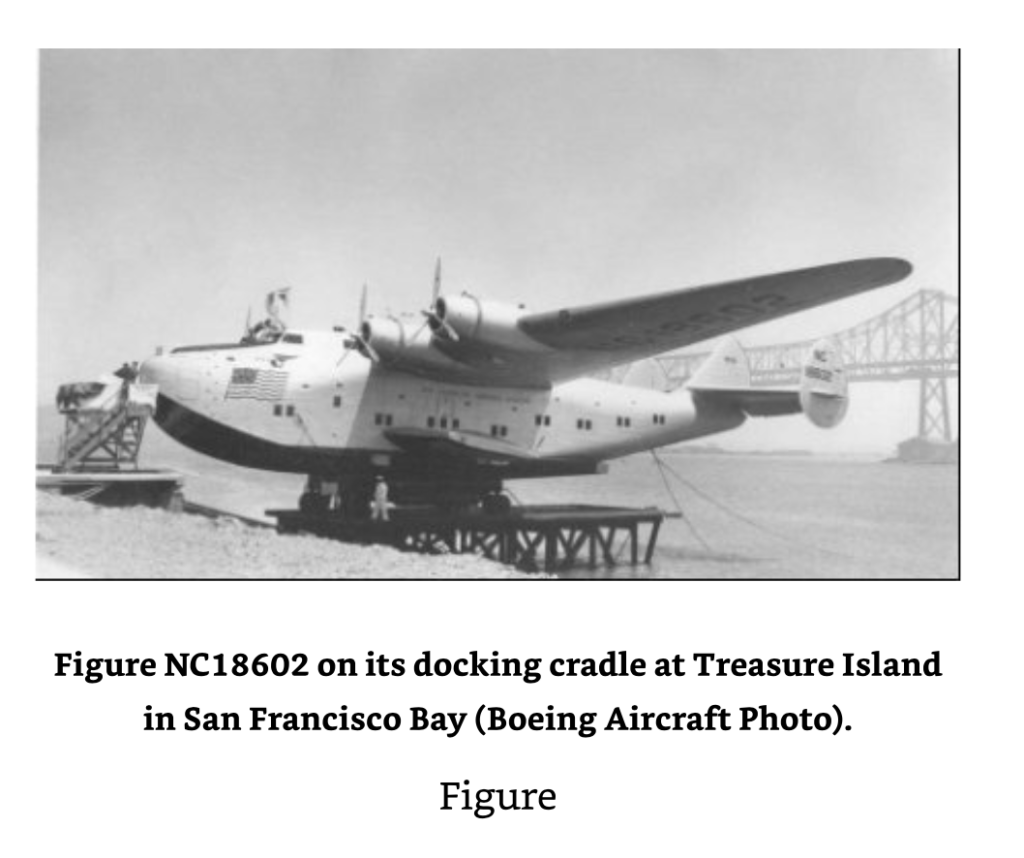

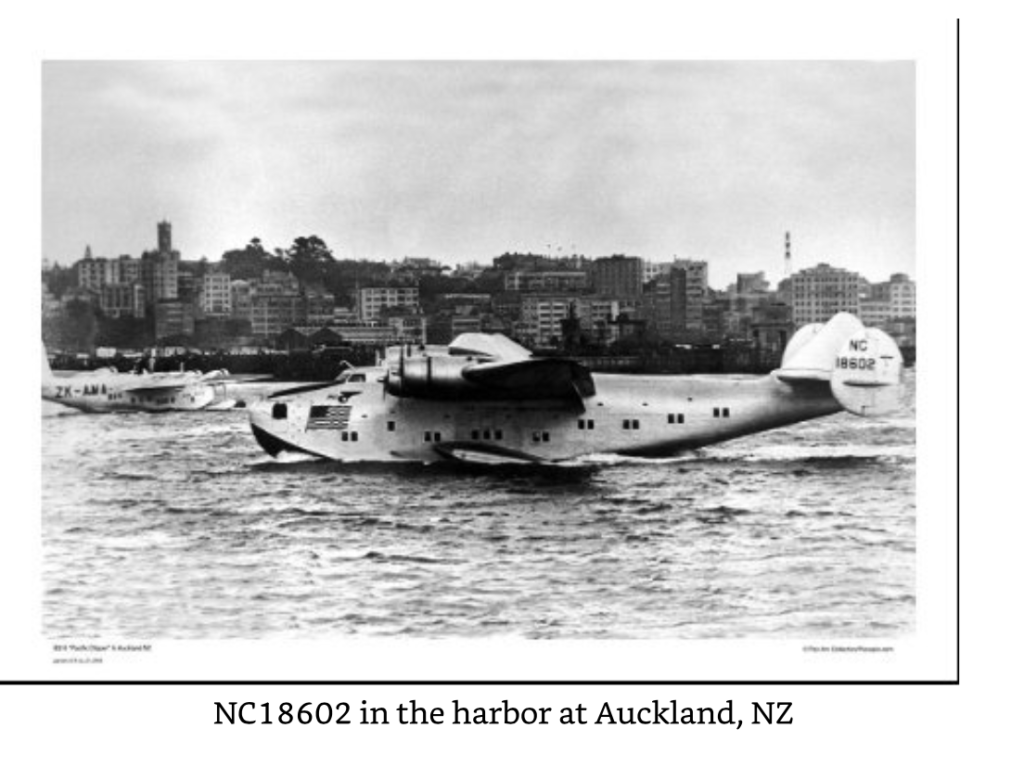

Pan American Airlines was a world unto itself for generations only coming to earth with a thud in the 1980s. Seeing references to it in reading, film, broadcast, and at the air museum at Pearl Harbor, I have wondered about its origin and development. An ember of that vague interest sparked recently when I read about an unintentional round the world flight in 1941 after Pearl Harbor (discussed in another post). I went looking for a corporate history and eventually came to this title. Having now seen in this book the development of flight up to 1941 I appreciate even better what a remarkable feat that 1941 circumnavigation was. That Boeing model had only come into use in late 1939 and had a litany of teething problems.

Though there are many books on Pan Am, few matched my interest. Many concerned famous incidents involving Pan Am machines or personnel. A good few picked over the bones of the final corporate demise. Even more prolific were books about fashions in dress or, ahem, undress. Did Mortimer in the back row mutter ‘Cheap sensationalism’? Yes, there seemed to be a lot of that. In sorting through this material Juan Trippe’s name kept coming up and the tidbits harvested clearly indicated that at least for some long time Pan Am, gargantuan though it was, was a one-man band. How could that be, I wondered? As much publicity as that celebrity CEO of General Electric (GE) Jack Welch got, his influence on the company was never emphasised. GE was a behemoth before Jack and remained that after him. Not so Pan Am. It seemed Pan Am = Trippe and Trippe = Pan Am. He made Pan Am and it did not outlast him nor did he it.

I flew on Pan Am once near its end in 1979 across the wide Pacific crammed into Economy on a flight when smoking was common. The cabin crew had been trained by Houdini and disappeared before one’s eyes. It was the same from New York City to Paris. Overall it was a ghastly experience. The only benefit after the safe arrival was that I now get to say that I once flew on Pan American Airways.

![The Long Way Home (2d ed) (2010 [1998]) by Ed Dover](https://theory-practice.sydney.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/9780615214726.jpg)