Blood on the Snow: The Killing of Olof Palme (2005) by Jan Bondeson.

GoodReads meta-data is 233 pages, rated 3.60 by 62 litizens.

Genre: Non-Fiction

Verdict: [Not what I was looking for and not much else.]

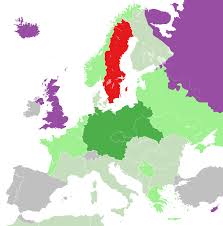

On 28 February 1986 Olof Palme (1927-1986), long-serving Prime Minister of Sweden was shot dead on the street in Stockholm at about 11:20 pm when he was walking home from a movie. Who dun it remains a mystery and with that why it was done. Into these voids much speculation has flowed.

Hedge: this is my only source though I did cast an eye over the entry for Palme on Wikipedia in the original search for a biography as explained below. Of course I remember him from the times as a lightening rod for many good causes and some not so good.

The author describes early police reaction as Keystone Kops: the panic line (+ 000, or 911) went unanswered, and the first person to call in the incident hung up before it was answered. When another caller got an answer, the officer taking call did not believe anyone would be shot on the street and regarded the call as a hoax. Only when two officers in a patrol car passing-by saw a small crowd gathering and stopped did police action, of a sort, start. Again their first reaction was that it was joke of some kind, nor did they recognise the fallen Prime Minister or his accompanying wife who, covered in his blood, stood stunned. These two hapless traffic cops seem to have had no training in management either crowds or crime scenes, and it got more chaotic as more officers and medics arrived.

The author describes all this in pitiless detail and more of the like was to follow, as no one seemed to have been in or taken charge of the investigation. Even when the realisation dawned that it was a shooting murder and then that the victim was the incumbent Prime Minister, the major crime or murder squads with their experienced detectives, forensic specialists, and equipment were not mobilised. Instead there was a stampede by senior police administrators for the glory of the case before world media, and the grandstanding started the very next day. Yes, there were press conferences, but no there was no management of the investigation. Indeed, in general one of the major faults the author finds is that the investigation was handled by administrators who themselves had no police experience.

The mass of witness statements collected, eventually, were contradictory and confused as any experienced officer (or reader of krimis) would expect, and the author narrates these on end, but never puts them in any discernible explanatory or analytical framework that I could fathom. The result is a confusing mass of detail with no contours which perhaps mimics the police approach.

The initial response of the grandstanders was to round up the usual suspects (druggies, pushers, violent criminals) and fit one of them to some of the eye witness descriptions (take your pick) of those around the time and place. When that failed the first grandstanders were pushed aside by the another lot who next went for foreigners (immigrants, refugees, or spies [Russian, American, South African, Iranian, Iraqi, Swedish, or in combination]). There followed a conspiracy theory focussed on a Bofors contract with India, implicating Indians, and a host of international arms traders. Then the police officers themselves became suspects as a way to explain the incompetence. There being no end to stupidity as we have seen in D.C., another school of thought was that his own immediate family murdered him, i.e., his wife and his son(s) either collectively or individually. Finally, well probably not ‘finally,’ there is also the belief that he arranged his own death as either suicide, or by cleverly swapping someone else so he could take off to a life of ease in one of the sunny but poor African countries he was always banging on about.

No doubt somewhere both Hillary Clinton and aliens have also been blamed. Check Pox News.

In each case vast time and money with attendant media irresponsibility went into the exercise to come up with nothing and the decades dragged by.

Because of the glory to be had in the case, the first officials to direct the investigation were managers who per the McKinsey testament had themselves no policing experience to influence, i.e., taint, their management activities. It is an article of faith in the Church of McKinsey, supported by faith alone and no evidence, that managers should not be contaminated with experience of what they manage. While that seems normal these days, and explains much incompetence, they must not have watched any krimis on TV either because they omitted the most basic procedures, like securing the crime scene, avoiding witness contamination, systematic finger printing, cross-referencing files, identikit pictures, and so on. (All these things were eventually done piecemeal after the fact.) These omissions were compounded by the desire to manage the investigation without assigning experienced homicide detectives in preference to officers personally dependent on and so loyal to the managers, including officers seconded from regional offices unfamiliar with Stockholm who were free of local prejudices, yes, but also unaware of the most basic geography of the city. The litany of blunders is Trump-like.

When the investigation proved intractable and the quotient of glory available evaporated these managers abandoned the project leaving no one in charge. Anyone who has worked in a large organisation has seen some or all of these behaviours by the McKinsey bots in our midst: The rush for CV glory; when things go wrong the flashing blame bat that strikes subordinates, the hasty departure before the trumpeted change fails, and so on. ‘Fail and Move up’ is surely a chapter title in the McKinsey manual.

If all one knows of Sweden is what we read in these pages, the real question is how such an unpopular, reviled, and despised man ever got to be PM. There are long roll calls of vitriol about Palme. It remains that the party he led won election after election, and when it lost it was by a hair. That electoral popularity might explain why he was feared by some, but this angle is not explored in these pages.

In these pages following the great tradition of blaming the victim much responsibility for everything is implicitly applied to Lisbet Palme, his wife, who was walking with him at the time of the murder. She went into hysteria and shock – who would not – but this obvious fact seemed to have escaped the notice of the on-site police officers (when they arrived) who said she was inconsistent and uncooperative. And in this case and all others that followed, cheque-book journalism ensured everything said under the veil of secrecy was broadcast within twenty-four hours.

After getting off on that note, she thereafter was reticent with the police – again who would not. Because the investigation was disorganised with even junior officers competing for glory, she was questioned repeatedly by different officers. In one notable instance four different sets of officers tried to interview her on the same day. And no they did not share their findings with each other, and in some cases no notes were taken in the name of secrecy, opening the door to wild speculation. It might be that she soon concluded the police were using her as a dupe – who would not – and she became ever less cooperative.

It is also pretty clear that some members of the Pox media did not want a resolution, but a continued melodrama with which to castigate authority. This is another angle omitted in this text. Rather like the 1970s murder of Australian journalists in East Timor which is periodically revived to boast circulation and hits, not to resolve the incident.

I wonder if any police investigation subjected to the same intense and enduring examination would prove to be similar? Mistakes are made, and concealed. Short cuts are taken and hidden. Officers are unfamiliar with or contemptuous of protocols. Equipment does not work. Analyst cannot use the expensive systems they have. And so on. I wondered that at the time of Chamberlain Trial(s). I did ask a judge of my acquaintance about this but he fobbed me off.

I also wondered what all those Swedes were doing on the sidewalks at near midnight in Stockholm on a cold winter night. There seemed to be many people dawdling about. Is that typical in sub-zero weather? Are those Nordics that tough?

For film buffs try Death of Pilgrim (2013), a four-part series, for a gripping account of one of the (many) subsequent investigations into the original investigations.

While mentally in the Nordic world I went looking for a biography of Palme but after reading the Kindle sample of the only one on that source I decided against it – breathless, sensation-seeking, and superficial journalism it seemed to me – and opted for the above title, though I did not like its sample any better – it read like a failed thriller script – but it came from Cornell University Press and that bespoke quality, a rigorous editorial process that would prize order, facts, dispassion, and analysis. And the blurb on the Amazon Kindle entry said this book would lay to rest the innumerable conspiracy theories. That seemed promising. So I had hoped when I pressed on. As if!