The Best krimi I read in 2019 was Dark Winter (2002) by William Dietrich

The citation reads ‘What an incredible setting at the edge of space. I discussed this krimi in an earlier post on this block. Have a look.

The Best krimi I read in 2019 was Dark Winter (2002) by William Dietrich

The citation reads ‘What an incredible setting at the edge of space. I discussed this krimi in an earlier post on this block. Have a look.

Book of the Year

The book [drum roll] is Laurent Binet, The Seventh Function of Language (2015).

The citation reads ‘Who would have thought such delightful libel could be published.’ I discussed this book in an earlier post on this blog. Get clicking’ for more info.

Stay tuned as other awards will follow on this site.

Robin Bailes, The Vengeance of the Invisible Man (2019)

Good Reads meta-data is pages 236 rated 0.0 by 0 litizens. (Lazy sods!)

Genre: krimi, academic

Verdict: Whoa! I did not see that coming.

Recovering from her Mummy’s Quest (2018) adventures in Egypt, Amelia has been digging in Romania. Romania! Yes, Rumania in the Carpathian mountains. Seems there are pictographs there, too, for her to interpret. In anticipation of Christmas she has returned to Cambridge and her sister, the high powered Zit who talks a mile-a-minute while running hither and yon. She is loud, full tilt, and one-dimensional, contrast to the shintrovert Amelia.*

Zit’s publishing firm is bringing out a work of fiction – Memoirs of an Invisible Man. In short order, the question becomes ‘Is it non-fiction?’ because strange things start to happen. The author does not show up at the book launch, but the books go flying through the air. Sales follow. There are several other public displays of the invisibility – a pair of empty trousers dance through Christmas shoppers, and so on. Nothing that would be noticed on King Street in Newtown.

The sensation hungry media adds to the fire garnishing invisibility with hyperbole. Sales continue to soar. Zit loves the sales but cannot communicate with the author, still less set KPIs. All of this intrigues Amelia, who read the manuscript and found it poignant, even moving, whereas, compliant with her McKinsey training all Zit sees only £’s.

In a parallel track professors two in Cambridge fastness have been strangled in locked rooms. Were they victims of collegial animosity. Well, as a matter of fact….. [But that would be telling].

Plod Harrigan applies the acids of questions, shoe leather, and patience to crack the case much to the fury of his superior who wants RESULTS! NOW! Bullying subordinates is certainly a chapter in the McKinsey Management Manual these days. Nonetheless, as he nears retirement Harrigan keeps on keeping on, despite the badgering, er hmm, management of his superior. Loved Harrigan’s musings about his last words, and pleased he did not need them.

Meanwhile, Amelia connects the dots between the murders and the invisible man. Seems obvious, and yet there are surprises to come. Believe me: I was surprised. Of course, they are connected but not in the way I expected.

A victim of her own curiosity, Amelia gets in the way and has a brush with the invisible one that frightens her into contacting Universal (see The Mummy Quest, reviewed elsewhere on the blog, for an explanation). She expected [sigh] the suave, dashing, handsome Boris to come to her rescue. Instead, thanks to the duty roster, she gets the short, unsympathetic, and dowdy Elsa who saves her neck more than once with a willingness to believe the unbelievable and a resourcefulness honed from previous encounters with the unbelievable.

In the midst of all this Amelia meets a man who does take her seriously and she him, but fitting courtship into a schedule dominated by the unbelievable is difficult. This romance is charming, but it does slow the action.

There are references to the formidable Maggie at the start and finish, but I was disappointed she did not put in an appearance. She just about stole the show in Egypt. The crystal ball suggests that she will figure in the next title in the series that will take us to Nosferatu country.

There are many great lines in what is essentially a screenplay. Elsa says that in her experience the dividing line between the living and the dead is a grey area. There are more where that came from. Read on.

Razor-tongued Robin Bailes (host of My Dark Corner of this Sick World to be found on You Tube) cannot be stopped, and in this one he comprehensively outsmarted this jaded reader with the double-barrelled plot. It brings together many threads from the cinematic suite of invisible man films discussed elsewhere on this blog. This is the third book in Bailes’s series, and the best for my AUD $4.95 on Kindle. Very clever. Chapeux!

*Shintrovert is a shy introvert, a term coined by Jessica Pan in Sorry I am late, I didn’t want to come (2017) discussed elsewhere on this blog. Do try to keep up.

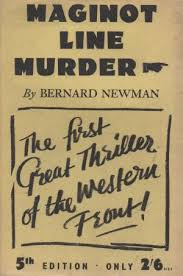

Maginot Line Murder (1939) by Bernard Newman

GoodReads meta-data is 219 pages, rated 0/5 by 0.

Genre: krimi

Verdict: Talky

Multi-lingual Brit secret service agent Bernhard Newman is rambling through the Vosges Mountains on his honeymoon, when….. Because of his experience in ferreting out German spies, Papa Pontivy, head of the French Deuxième Bureau, asks for his help. In the inner sanctum of a fort on the Maginot Line a dead body has been found. That is bad. Here is what is worse. The deadman is unidentified. Worse. Worst: he was shot dead but no one heard anything. Oh, and the corpse was naked and disfigured, to prevent identification it seems. How is it that no one noticed all of this in the claustrophobic confines of the underground fort?

How did a stranger penetrate the many defences of a Maginot Line redoubt? Sacré bleu! How did he do so in secret? How did someone else kill him without leaving a trace? All good questions.

After a tour of the fortifications Newman goes about his honeymoon business….ahem. And Papa Pontivy takes over. He disregards evidence and relies on his numerous instincts. Gallic though he may be he does not practice the Cartesian method, which in general is to accept nothing as true until verified beyond doubt, to divide the problem into its smallest components, to take each component in turn, to start with the easiest and (re)solve it and then on to the next. To make enumeration complete and reviews general so that nothing is omitted. Pops does none of this.

Thereafter the novel violates most rules of fiction. It divides the action and the narrative voice. Newman leaves. Pontivy takes over insisting on his instinct, which by the way make no sense but reference to his instinct is constantly repeated to the point where I agree with one of the characters who says to him, ‘I am tired of hearing about your instinct!’ Amen, brother! He then goes to Brittany which his instincts tell him is the key to the Line. He does not bother to look at a map, but relies on the writer to prove him right.

This instinct that he cannot stop talking about when Newman says a Captain seems to have recognised him (Newman). That sets Pontivy off but it is not his perception at all but Newman’s. And even that makes no sense since the Captain certainly recognised him since he had earlier encountered him in the woods and marched Newman in to explain himself. One rule for writing fiction is, I know, write fast and do not read what is written. This author applied that rule to the hilt. I kept going because of the few details about the Maginot Line, but as a krimi it is tedious.

Bernard Newman (1897-1968) was a prolific author. He had been a liaison officer with French forces during World War I. After this war he travelled widely in Europe on a bicycle. He was in France in May 1940 and saw for himself the onset of the German invasion. He often made himself the protagonist in his novels as above.

His oeuvre includes travelogues, spy stories, science fiction, and journalism. His The Blue Ants (1952) described a nuclear war between Russia and China set in 1970. There are nearly a hundred titles in all listed in the Wikipedia entry. Some have been re-issued in a Kindle format. Probably not for me.

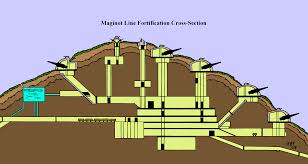

Confession. As a boy the encyclopaedia we had at home featured an extensive entry on the Maginot Line which fascinated me. Later I appreciated the political and social aspects of this engineering feat, and that added an informed layer of interest. André Maginot had served in the trenches at Verdun in World War I and he marched with veterans at the consecration of the tomb of the unknown solider in the Arc de Triomphe after the war. He entered politics to prevent another blood bath, and when he was invited to join a cabinet he wanted Defence so he could build that wall that later bore his name, though it was never officially named.

There were two major military reactions to the bloody stalemate of trench warfare in World War I. One was to turn to mobility in tanks, trucks, motorcycles, and air planes. Proponents of mobility included Winston Churchill and Charles de Gaulle, both of whom had also been in the trenches, and also Erwin Rommel who had practiced mobility on the Italian front in World War I. But Churchill and de Gaulle were marginalised in the post-war politics.

The second response was to build impregnable trenches under nine feet of steel and concrete which itself was under tons of earth. Maginot was one who responded in that way, but more importantly so was Phillip Pétain, the defender of Verdun, and his word was law on military matters because of the sacrifices at Verdun, birthplace of Jean d’Arc. This was an effort to learn lessons taught in blood.

Most of the lore about the Maginot Line is mistaken, like most lore. It did not continue along the Belgian border because the Belgians vigorously objected to that, and claimed that their neutrality would be respected, and if not, then their own Albert Line would suffice. In either case no unnamed (German) invader would threaten France through Belgium. When came the test, the Albert Line was breached in a few hours – it had been built by the lowest bidder, a German firm that turned over all the plans to the Wehrmacht. That may sound dumb. So does contracting with Chinese-owned firms for defence computers but we do that right in the wide brown land. Nonetheless, Maginot was determined to continue the Line to the coast, but he ran out of money and because of the Depression he ran out of political support. One of the reasons the Germans attacked when they did, was to strike before the Line reached the coast. Where it was tested in the South, it proved impervious to Italian attacks.

The Maginot Line was built:

In the polarised whirlwind of the Third Republic, the French general staff forgot its own strategy and spread men and material along the Line so that there was no concentration and in a crisis none would be possible. Consequently, the Line was fully manned, leaving no troops in reserve for such a counter-attack.

I read this novel years ago in the Fisher Library copy. It has not improved with age.

Not to be confused with Double crime sur la ligne Maginot (1937), a film that depicts a love triangle among officers in the Line and offers so many images of the formidable Line and hundreds of troops that it must have been made with the cooperation of the army, perhaps as propaganda to show how great the Line was. In the event, German agents were the villains. There is a version of it on You Tube, and it is dead boring.

William Dietrich, Getting Back (2000)

Good Reads meta-data is 370 pages rated 3.70/5.00 by 199 litizens

Genre: Sy Fy

Verdict: Mad Max réchauffé.

In the near future all the world’s problems have been solved by United Corporations which has a place for everyone and everyone is in place. Life goes on according to McKinsey management über alles. Each person is a good employee and a good consumer and that makes the world of twelve billion go around. But for Dyson it is boring, boring, boring, boring. It is as tirelessly and tiresomely predictable as the ideological squibs from News Corporation’s hacks. (Is that possible?)

The world is neat, clean, orderly, a kind of benevolent Big Brother society without the personal touch of Big Bro. Dyson is lazy at work, makes asinine remarks, and generally acts like an adolescent. He made me think of that midget, old what’s his name, Tim, or Tom, or Gone. He comes into contact with mysterious, glamorous Raven who tells him there is an alternative – Australia!

But wait Australia is a dead continent, thanks to the ScoMo Virus thirty years before. It is one big exclusion zone, now all but eliminated from the only source of human consciousness, Wikipedia.

Much of the middle of the book is how Dyson got there which I will spare readers. The point is that Australia has returned to its history and become a dumping ground for recidivists (look it up) criminals who are called morally impaired. (I tried not to take any of this personally.) See the reference to Mad Max above. Also dumped there are malcontents, misfits, and the likes of Dyson who are high-maintenance, squeaky, unproductive wheels. There is a twist to that at the end that seemed irrelevant to this reader.

The bulk of the book is survival in the Outback, surviving the morally impaired, surviving the relentless climate and distances, surviving Channel Ten testosterone broadcasts, and using the Australian salute. There are a few natives who, against the odds, and unknown to United Corporations, have survived the ScoMo Virus, becoming white aboriginals. A nice touch that. The smarty pants do not heed the advice of these oddities because it is vague and spooky. They should have.

True love conquers all, and in the end Raven saves Dyson and they start a new life. [Cue violins.] This is all ground he covered again (and better) in The Murder of Adam and Eve (2014).

Dietrich goes to the ends of the earth for his fiction, others have been set in the remotest Africa, Arctic, and the Antarctic, and while there are no acknowledgements in the Kindle edition I read, it is likely that he spent time in the Outback to write this tale.

I wonder if he came across any of Arthur Upfield’s Outback krimis? Shoulda.

Goodreads meta-data is 360 pages, rated 3.4 by 104 litizens.

Genre: chick phil

Verdict: More Voltaire!

Harassed, transplanted mother of three and aspiring novelist caught in a maelstrom of home renovations in an alpine village where school girl French is no match for the Vaudois accent is going spare while husband and father commutes long distances and works longer hours in Geneva saving the world for a Red Cross agency. She is close to breaking when….

Then one Saturday morning in mid-catastrophe of sick children, kaput hot water heater, overnight blizzard, absent husband, an oddly dressed chap appears in the house and who speaks a stilted English and reassures her all is well. She finds that strangely comforting until she realises he is not the doctor in fancy dress come to see her children and that no one else can see him. So it begins.

Misses is well schooled in Topper films and The Ghost and Mrs Muir and knows what not to do – no blurting, no blabbing. Disconcerting though the apparition is, he translates the Vaudois patois into English for her, much to the shock of some of the workmen lounging around the house on the pretext of repairing something. That jolt pleases her no end and she cuts the apparition slack.

Thereafter her visible invisible man is ever present, and he wastes no time in letting her know he is V O L T A I R E and is SHOCKED to learn that she has never read a one of his innumerable works and countless words. Pas un mot! Incroyable! To placate him she sits him down at the PC to read his Wikipedia entry which he begins to edit. They have bonded into the odd couple in this journey.

The author wisely does not try to explain everything in the interest of keeping up the momentum. Where did de V come from? Why is he there? How does she keep from blurting out his presence? How is it that his ectoplasm can strike letters on the keyboard but nothing else, and why does it react so strongly to the smell of coffee? De V adjusts quickly to some things like Wikipedia and he is flummoxed by others like doors. Though the author cannot forbear a tedious backstory. Too bad. That certainly brings the momentum to a halt.

Indeed at halfway through the backstories of the author – boring! – supplants V. That is a fatal error. Her backstories of drunken and lecherous journalists are as dull as the ideological prose such hacks regurgitate everyday. If I wanted to keep up with such twits I could read the Australian newspaper, if it could be delivered to my remote fastness.

Although I did find arresting her story of the effort of an African president, while being interviewed, to rape her as he denounced humanitarian imperialism. She had wanted to question him about the murder of international aid workers in his country. Then she understood why he only granted exclusive interviews to women. Something the hacks had figured out long ago, but did not bother to pass along. Such is the sport. Fortunately the president was a smoker and a heavy ashtray came to hand.

‘Humanitarian imperialism,’ a quick check with Professor Google confirms, is much denounced by PhDs. More than thirty thousand hits on books, articles, symposia, and op-eds from the learned. Nothing surfaced about either rape or murder as the antidote to this scourge.

Back to Vaudois, also amusing was the temerity of the newcomers to question Swiss Rail when a minor accident occurs at the local train station. The incomers raise the question of procedure in rail safety, and a stunned silence follows. No one questions Swiss Federal Railways (SFR, SBB, CFF, FFS, or VFS) by any of its many names. To do so is worse than swearing in church. Gasp!

Once an American tourist opened a window on stuffy street car in Zurich and the whole coach load of chattering passengers who had been fanning themselves fell into an astonished silence, shocked that anyone would take such a liberty without seeking written permission from the Federal Council.

GoodReads meta-data is 383 pages and it is rated 4.06 by 1246 litizens.

Genre: Chick Non-fic

Verdict: A cackle! Then a bore.

Executive Summary: Dedicated introvert bites the bagel and tries to live as an extrovert for one year. Disasters follow.

Long Summary: Self-diagnosed Shintrovert* (shy + introvert) goes all out to be a self-confident extrovert and talk to anyone and everyone on the street, on the bus, in the supermarket, in London. London! That was bound to fail. Luckily she was not charged with numerous violations of civil code of mutual indifference that rules Britannia.

The phrase in the title ‘Sorry I’m late, I didn’t want to come’ is her main social gambit. Maybe that explains a few things right there. She seeks professional help from a variety of consultants, while using friend apps. Do such things exist? Yes, they do. Both the consultants and the apps are real.

The social media apps match isolated loners with other isolated loners, although neither of them admits to it, with a view to a meeting. Some of these meetings consist of awkward silences, others are trips to a film where nothing can be said. Progress on extroversion scale: 0.

The consultants are varied, one teaches her to be charismatic by smiling, nodding, and offering a firm handshake. Was that Hitler’s method? Gandhi’s? Now we know. Others heckle her to thicken the social skin. Both get paid. Another listens to her talk and then gets paid. [No comment.]

She also reads the abstracts of social psychology journals to lard footnotes through the pages. Cargo cult: If is is in print, then it must be true, right? Check out Pox News for the latest on that.

I did keep flicking the pages but it got so-o-o-o repetitive. It is like far too many clever pieces published in the New Yorker magazine that are then puffed up into a book. Emphasis on puff. At sixty pages it was an amusing ride, at 383 (!) it was as tedious as a continuous family get together for Thanksgiving that lasted a year (with no survivors.) It went on and on for no other reason than to go on and on than to tear pages off the calendar.

Alright already, I know that many readers take it seriously as a psychological self-help guide, but you don’t have to be sick to laugh out loud, and I did. As usual the legion of GoodReads reviews are therapy for the writers and uninformative for the reader. Par for that course.

*Shouldn’t that then be ‘shy-introvert?’Autocorrect objects to both versions so nothing to choose there.

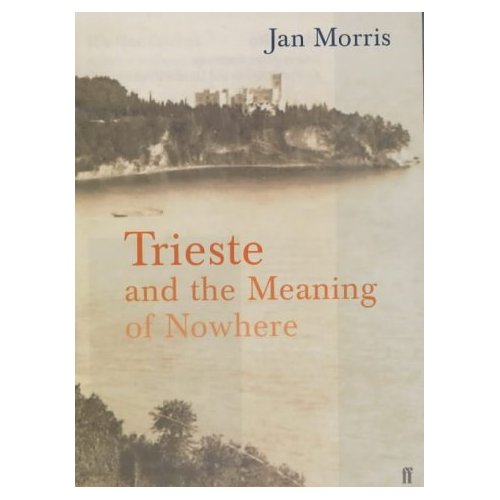

GoodReads meta-data is 208 pages, rated 3.98 by 116 litizens.

Genre: Travel

Verdict: languid and insightful.

Morris first set eyes on Trieste in 1946 as a soldier in the British Army, then near to fifty years later Morris returned.

When Trieste had been in the Austro-Hungarian Empire for nearly a century it was the port of Venice at a time when the Hapsburgs, at the height of their powers, developed maritime ambitions in the Adriatic. To link it to the capital, all-weather roads and railways were built over the mountains while the harbour was dredged, and made modern. Vienna was the seat of a vast empire and home of a royal house that had once extended from the Carpathian mountains to the Pacific Coast of Mexico. It was rivalled only to London and Paris as a world capital at its peak, and Trieste was its nautical doorway for those years.

Trieste only became Italian by dint of others, and like its neighbour, Venice, it has never felt itself to be Italian, but rather a world of its own with its own language, mōres, and manners. And that is what it was in 1946 when a callow Morris arrived with the 2nd New Zealand Division, to a Free City under the aegis of the United Nations, while national borders were resolved in the jig-saw puzzle of the post-war Balkans. Both Italy and Yugoslavia advanced claims for it, both for the same reason: as a buffer against the other, i.e., neither wanted it for itself. While those tensions played out the city was divided and occupied as Vienna was for a time. In Trieste it was Kiwis on one side and Jugs on the other for a time in an uneasy fait accompli.

Berlin was divided and occupied and so important no one would yield a centimetre thereby spawning a vast culture of art and literature about that long-divided city. Vienna was divided and occupied for a time and Graham Greene immortalised it in ‘The Third Man.’ Trieste was divided and occupied and no one noticed, not even many Triestinos.

Today Trieste is in if not of Italy, but the city lies within a few kilometres from the successors of Yugoslavia, Slovenia and Croatia, once the hinterlands of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As the guns of August unlimbered in 1914, it was through the port of Trieste that the remains of the slain Archduke passed on the way to Vienna.

But to revert, at the end of World War I Italy got title to Trieste as a spoil of war for being on the winning side after the blood bath at nearby Caporetto with the result that the city lost its raison d’état for it was then shorn of its hinterland and the capital it had been developed to serve, namely Vienna. No longer glowing in the reflected glory of Viennese art, culture, literature, music, power, or commerce, Trieste fell into the torpor of a melancholy lassitude where it was content to remain far from any beaten path.

Proof of its irrelevance is that it was all but untouched in World War II, not being important enough for anyone to bomb it to smithereens, and when Italy changed sides in August 1943 neither partisans nor fascists bothered much with Trieste, since it had offered no material, strategic, or symbolic advantage. Ergo there was no rush to get there and fight over it. However it bears scars of that war in another way, as the locale of a Nazi charnel house at San Sabba.

In the parade of names of Triestinos only Italo Svevo meant anything to me and that was very little, as the author of ‘The Conscience of Zeno.’ By the way ‘Italo Svevo’ is a pseudonym for Aron Schmitz.

Marie-Henri Beyle (Stendhal) served as French Consul there. While his most famous novel is Le Rouge and le Noir, for my money far more interesting is the one set in Italy, namely La Chartreuse de Parme. Though he preferred cosmopolitan Milano to the backwater of Trieste.

James Joyce spent much time there pencilling his incomprehensible Ulysses, which Morris by-passes ever so delicately.

Illy coffee stems from here where the family remains. We have been loyal imbibers of Illy for many a year in its red, blue, and pink banners.

Much of the book is Morris musing on life, and it is so well done that I, curmudgeon first class that I am, have no complaints. Indeed I hope to read more of Morris’s books in due course for sheer pleasure of the effortless prose.

Effortless to read, but no doubt it takes quite an effort to achieve that.

There is a story of an aspiring young writer visiting Anatole France, famed for his elegant yet simple prose in many novels. The ingenue was shown into the master’s study where France was at work surrounded by a mass of pages, doodles, crumpled-up balls of paper, pages of cross-out done with such vigour as to tear the paper, and more discarded pages overflowing the bin. Seeing the eyes of the would-be acolyte noting the mess, France said, ‘this writing, it is not so easy as it looks when it is done.’

We spent four nights in Trieste in 2019 and enjoyed it. I noticed several posters called for a Free State of Trieste.

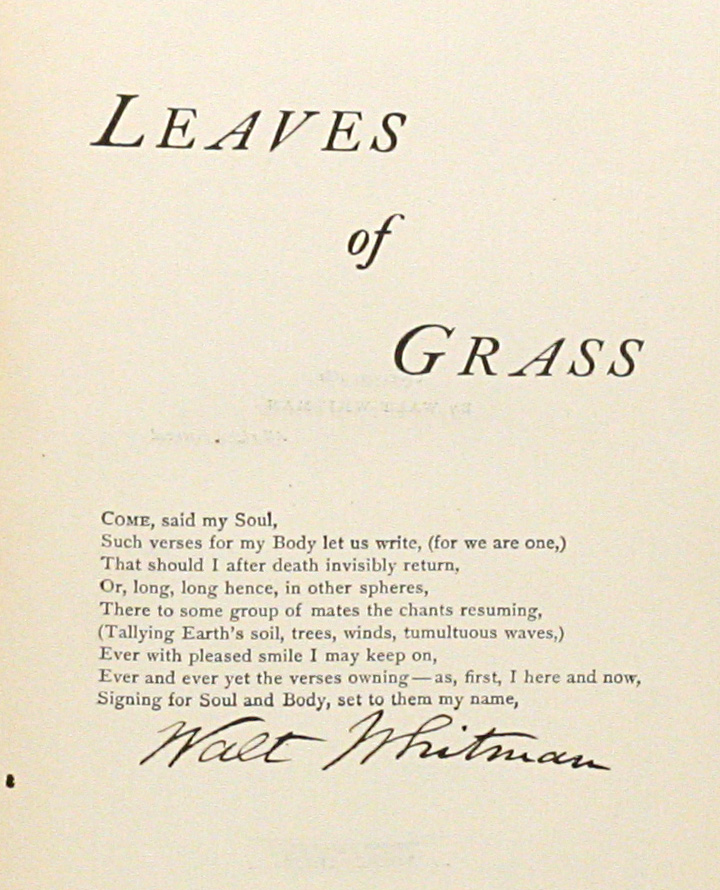

Good Reads meta-data is 624 pages, rated 4.1 by 81,342 litizens.

Genre: Poetry

Verdict: Exhilarating!

To say that Whitman’s poetry is exhilarating is just a start. It zips, it dips, it soars, it flies, it ponders, it races in a cascade of verse. About 400 poems are combined in this book, which began as a collection of twelve, and became his life’s work as he revised, edited, amended, and augmented it.

It also departed from the conventions of poetry in its celebration of the immediate, material world and the human body in contrast to the mannered abstraction that prevailed at the time. The verse is blank, by the way, and rhymes are few and far between, and that also made it odd. For its time it was also explicit about sex, and implicit about homosexuality.

No one in the literary establishment would touch it in 1855, as a consequence he printed it himself in the 95-page first edition. (One sold in 2014 for $US 305,000.)

The narrative voice is without a doubt Whitman himself (and sometimes that is explicit in the verse) as he surveys man, woman, child, beast, and nature. He sees himself in all the others and they in himself. When he sings of himself he includes one and all, slave and free, male and female, living and dead, victorious and vanquished, owner and drudge, lilac and rose, dog and cat, vegetable and mineral, high and low, black, white and red, yellow and black, urban and rural, owner and labourer, prostitute and lady, believer and atheist. The tone is ever affirmative, though the later entries, forty years after the first edition, and after his years as an ambulance driver in the Civil War, and after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, shade into melancholia. One of his duties as a driver was carting and burying amputated limbs.

It was denounced from the pulpit, banned in Boston, and burned as obscene. That free publicity increased sales. When reviewers tore into his work, he published these reviews in the following editions of ‘Leaves of Grass.‘ At one point a thousand copies were sold a week for months on end. New printings were invariably new editions as he included more poems and more hostile reviews, and they sold out in a day.

By 1919 it had become a part of the American literary canon though quite how that came about it is a mystery in the vigorously contested Wikipedia entry. Who championed it passes in silence in this wordy but vague entry. But more than one reader puts Whitman in the pantheon with Shakespeare and Dante. Well, this reader does.

These days PhDs earn tenure by finding fault with the poems, with Whitman, with the air he breathed. There are a few sips of this bile in the Wikipedia entry. Confident this reader is that Whitman’s verse will outlive all the spite and spittle of these pygmies.

Quoting lines and passages do not do it justice. It was meant to heard and I listened to it in Audible edition that is superb. Robin Field’s voice is not distracting, the diction follows the cadence of the prose, and brims with energy, as it should.

Below is a list of some of the individual poems:

By Blue Ontario’s Shore,

O Captain! My Captain!

Dalliance with Eagles,

Faces,

From Pent-Up Aching Rivers,

I Sing the Body Electric,

Native Moments,

The Open Road,

The Sleepers,

Song got Myself,

Spontaneous Me,

Song of the Open Road,

To a Common Prostitute,

The Untold Want, and

A Woman Waits for Me.

During World War II it was one of fifty books distributed freely to members of the US Armed Forces and auxiliaries as exemplars of Americana. What would be distributed today? Surely not books, but videos to reflect one hundred and fifty years of free public education in which literacy has declined. Perhaps it would be episodes of ‘Say Yes to the Dress?’ Or a collection of garbled tweets from a twit.

Whitman was fired from his day job by his boss who read a few pages and found it filthy. The grass of the title by the way is in the hand of a child which the narrator says is the handkerchief of the Lord.

Some of the entries on Good Reads reach a new low of self-indulgence, even for that forum, when a one-star rater admits to not reading such filth. Others offer anagrams of the title that reflect their scatological personality. Fatuous as these entries are the authors took the time and trouble to post them. As usual most of the comments are about the commenter and not the alleged subject.

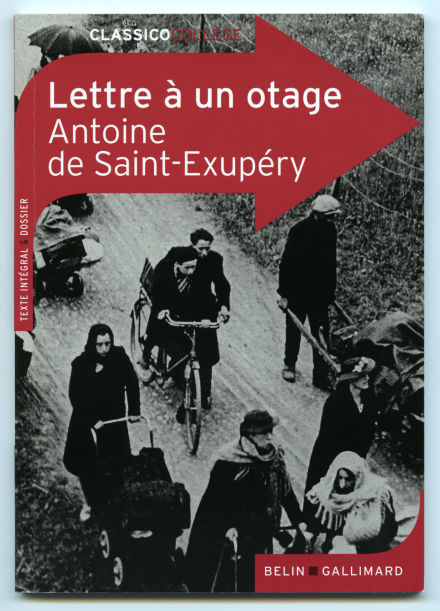

Goodreads meta-data is 39 pages, rated 3.93 by 594 litizens.

Genre: Musing.

Verdict: A period piece.

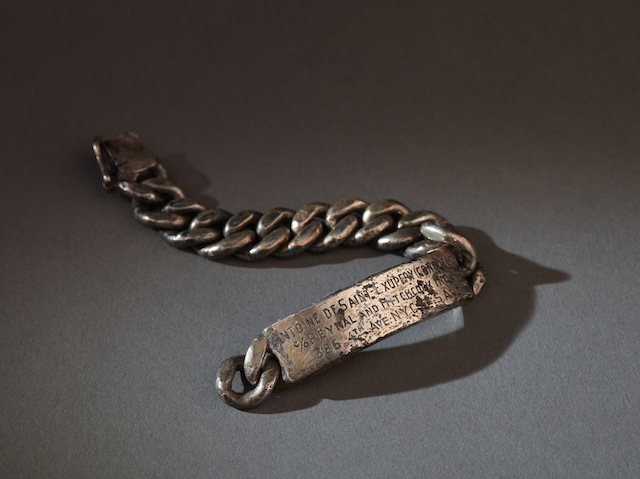

Though it celebrates the grit of his comrades in facing the Nazi juggernaut of 1940, the pamphlet was banned in Vichy France because it was dedicated to St Ex’s very good friend and the captain whom he admired, Léon Werth, a Jew. St Ex got out but Werth did not. It takes the form of an extended letter, musing on life that does go on. Ironically St Ex did not survive the war but Werth did. Slight though it may be, St Ex has as always an uncanny knack for finding the le mot just each and every time, some lyrical, and some mournful.

The first draft was to be the preface to Werth’s novel, Trente-trois Jours, about the Defeat and the flight of refugees. But when Werth went into hiding in the Jura, and St Ex escaped to Lisbon where he revised it into a more general reflection on time and place and recast Werth a symbol of all of France.

That is why the Vichy authorities banned it. Treating a Jew as French was bad. Explicitly admiring this Jew for his patriotism was worse. But making him a symbol of FRANCE was intolerable.

As always with St Ex the sky is there, and so is the sand of the Sahara.

Yet even here idiocy is to be found. One reviewer on Amazon says that St Ex ‘fought valiantly to keep France from becoming Socialist at the hands of Charles De Gaulle, and it probably cost him his life.’ Yep. Was that a Tweet from the Twit in Chief? There is no point in trying correct this nonsense, best just to savour it.