On the bridge of the starship Enterprise all eyes bored into the captain, who was locked in the most difficult negotiations of his career in space. Once again the Enterprise had found new life. The bald captain, determined to establish peaceful relations with it, bent all efforts to the task. Everything was on the table. At that very moment he had agreed to decommission all vacuum cleaners in the Alpha Quadrant! Why? Because the dust mites he was bargaining with had demanded it. That point conceded, the captain took a break and ordered a cup of tea from the wall, ‘Earl Grey, hot.’

Peter Singer belongs on the Enterprise. Members of its crew treat microbes with respect and eat energy, not matter. They have eradicated poverty by converting energy into matter in replicators from whence the tea came. This is the world Peter Singer wants.

For more click on the linked file:

Download file

Category: Book Review

‘Pictures from an Institution’ (1954) by Randall Jarrell (1914-1965)

Good Reads meta-data is 286 pages, rated 3.59 by 393 litizens.

Genre: Novel set in the academy, so an academic novel

Verdict: Malice aforethought.

A series of picture post cards of the people and their activities in a progressive women’s college in the uplands. Benton College is populated by administrators, professors, spouses, children, and even some students who in the conscientious and self-conscious spirit of the times improve each other. All are observed by Gertrude, a neurotic and vitriolic New York City novelist, spending a semester as writer in residence (while collecting material for her next unsuccessful sarcastic study of the human condition), while she herself is observed by the narrator.

There is no plot and nothing happens as the academic year passes from the faculty reception in the fall and yet I kept reading. The incidents and types are so familiar, from the earnest college President who spends all his time raising money with a beneficent smile, encouraging everyone to call him by his first name, Dwight. Then there is his South African-born Boer wife who seem his antithesis: dislikes anyone and everyone and communicates that by looks, silences, and now and then word.

Some professors have attained their high position because no one has ever understood anything they have said, such is the thickness of the Viennese accents. Others are such relentless do-gooders that it surpasses belief. All peaked at the PhD which left them depleted and fit only for this backwater in the eyes of the aforementioned novelist. Well, one had published a review in ‘Dial’ in 1929.

Then there are the obligatory dinner parties among faculty members who revile each other but affect bonhomie to grease the wheels of life. No sooner have the guests arrived than everyone wishes they could leave but they cannot. There is no ‘Who is afraid of Virginia Wolfe’ drama, only a well rehearsed dance of words that pass the time slowly.

The haughty novelist is a stand-in for Mary McCarthy who had published ‘The Groves of Academe’ (1952) after being a writer in residence at Sarah Lawrence College. I have read it long ago without recollection.

What follows are some examples of Jarrell’s prose filleting. Since she is the centre of attention, we start with Gertrude:

She would have come from Paradise and complained to God that the apple wasn’t a Winesap at all. Page 9

For her mankind existed to be put in its place. Page 13

She looked at me the way you’d look at a chessman if it made its own move. Page 36

“That beige snake,” “that—that soulless woman,” as her two last best friends had called her. Page 74

Her mien was one of impatient astonishment at the stupidity of the world. Page 95

Malice lived in Gertrude as though in nutrient broth. Page 133

The Viennese music teacher’s speech’ was a pilgrimage toward some lingua franca of the far future.’ Page 13.

But he is given many bons mots, e.g., ‘De devil soldt me his soul.’ Page 136. Said to explain the ease with which he composed tunes for all occasions.

Benton College and its progressive education gets the knife, too.

While the faculty members indulged the students to the Nth degree, there was one allowance they never under any circumstances made—that the students might be right about something, and they wrong. Page 81

Education, to them (the teachers), was a psychiatric process. Page 82

The faculty at Benton longed for men to be discovered on the moon, so that they could show that they weren’t prejudiced towards moon men. Page 104

To get an A the student had to believe what her professors believed. They had to make up their own minds, true, but only when their own minds matched those of the professors were they educated. If they thought they had made up their own minds and it diverged from the Benton way, then they were in for more more study conferences, more careful and patient understanding, more mutual improvement, until that Day of Grace came. Page 105-6.

These stabs and others are brilliant, however, there is much dross as the book goes on and on and on. I did flick Kindle pages to the end, a tribute to dedication.

Jarrell made a name as a poet and a critic, and was famed for his barbed aperçus such are on display above. ‘Display’ is the right word because this a demonstration more than a novel. It demonstrates his many talents to make a cloud of words out of nothing at all. In this way it is rather like the pastiche of a middling Woody Allen film. There is much verbiage signifying nothing; it ends on page 236 because he stopped typing, not because of any conclusion. His poetry is spare and terse, but not this garrulous prose.

Jarrell’s most famous poem is the five-line ‘The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner.’ Jarrell had served in the Army Air Corps during World War II. Many of his poems concerns army life and the fears and hopes of draftees, like ‘Eighth Air Force,’ ‘Gunner,’ ‘Mail Call,’ ‘Hope,’ ‘Losses,’ and more. He himself had volunteered. He survived the war to be killed in a car accident crossing the street.

‘Flight to Arras’ (1942)

‘Pilote de guerre’ (1942), translated as ’Flight to Arras’ (1942) by Antoine de Saint Exupéry

Good Reads meta-data is 168 pages, rated 3.9 by 1852 litizens.

Genre: Non-Fiction

Verdict: ‘Like glasses of water thrown onto a raging forrest fire,’ that is St X’s description of the futile and pointless actions of his Reconnaissance Group II/33 in May and June 1940 when half of the planes (seventeen in all) and crew (more than fifty men) were sacrificed in meaningless and often fatal efforts to stem the blaze that erupted from the impassable Ardenne.

Somehow St X and the other half of Group II/33 survived. He flew at least six combat missions at five hundred feet, well within range of small arms fire, to say nothing of anti-aircraft cannons. There is a remarkable description of a plane surrounded by a basilica of light with yellow candle flames rising to meet it. It is, of course, caught in search lights and the tracers of gunfire assail it.

He flew a Bloch 174. The navigator, photographer sat in the glass nose cone, while the pilot and the rear-facing gunner sat in the upper glass bubble.

He flew a Bloch 174. The navigator, photographer sat in the glass nose cone, while the pilot and the rear-facing gunner sat in the upper glass bubble.

The book is replete with his descriptions of flight, musings on life, and observations on death which he found a constant companion. He also emphasis the dutiful way in which members of his Group II/33 went about the business with neither histrionics, panegyrics, excuses, or delays. When it was one’s turn to fly, one flew, no matter how suicidal it seemed and sometimes was. St X took his turn and his chances along with the the others. It compares in the desiccated tone to Marc Bloch’s ‘Strange Defeat’ (1944).

As he sits in the cockpit warming the engines, he muses on his childhood bicycle rides through oak forests which he likens to clouds. As always his prose is elegant and elegiac. Then comes the harrowing moment in flight when the rudder will not respond and the tricks to free it do not work as the Messerschmitt 109s approach. Then at the last minute the Germans diverted to a better target.

That straight forward account of courage and grace under withering fire found a ready audience, and though the book was banned in Vichy France and worse in Occupied France, clandestine copies circulated widely. It was banned not because it portrayed the war against the Occupier so much as because in it St X praised a Jew who led by example, noted the thanked the dedicated communists in the ground crew who overcame impossible problems, and complained about the generals who orchestrated the chaos from a safe distance many of whom later found a billet with Vichy.

He wrote it, while in the States to explain, to justify the French after the Defeat by showing that many Frenchmen did their best in an impossible situation, leaving almost 100,000 of them dead. (Leaving aside of course the fact that the impossible situation had been made by a good many Frenchmen over several years, a lot more than just a few generals brewed the soup, and that St X himself never had any interest in the broader society until it impinged on him in Group II/33.

St X rejoined II/33 in Corsica in 1944 from when he flew into legend, perhaps landing on Asteroid 325 also known as Asteroid B-612.

‘Mr Campion’s War’ (2018) by Mike Ripley

Good Reads meta-data is 256 pages, rated 4.0 by 40 litizens.

Genre: krimi

Verdict: Albert, shut up!

While Albert Campion never shuts up, he says very little, and he has never said word one about what he did during the War 1939-1945. He talks and talks, sometimes even in English, but there is little sense in it. Rather it is adolescent wit, word games, bon mots, Latin tags, fragments of misremembered poetry, and so on. To say he is loquacious is just the beginning.

In these pages he is full flight on his seventieth birthday in the Dorchester Hotel on Park Lane in London surrounded by admirers and acolytes, well, family and acquaintances whose tolerance is high. They all know each other, having endured Albert in different configurations over the years. There is Plod from the Yard, too. Lugg the man mountain and bounded retainer is also there to be make a nuisance of himself, and he does.

But among all these Britishers there are, there in England, in 1970, there are….foreigners. They are the Spanish Vidals, mother and daughter, a glacial French woman, a wall flower Frenchman who is quickly forgotten, and an avuncular German, and among them the talk turns to the War. Have these foreigners come all this way to wish Albert a happy birthday? Well, maybe… ‘Ha!’ That’s a laugh. They have come for their foreigner purposes. Or have they?

We have a parallel progression. Albert spills his tale from 1942 in every second chapter, while in the next the guests at the party mix and (mis)match. It takes a scorecard to keep track of everyone at the party, and it turns out that most of them are blue herrings, but not all. The two stories merge when the very large, very sharp knife for cutting the cake disappears, only to reappear in the German.

Quibbles I have a few. No one seems to take much notice of the disappearance of the very sharp knife early in the piece. C’mon, haven’t they read any krimis? This the beginning of an opportunistic crime for sure. Course if they had investigated the case of the missing knife, the story would have ended with that.

Nor does anyone seem much interested in the German once he has been stabbed.

Supernumerary Lugg ambles about being rude and crude, and that’s it. He serves no purpose. His speciality it seems is serving no purpose, but he (dis)attracts a lot of the reader’s attention.

Because the three foreign women have different, married names in 1970 than those in the 1942 telling this reader was never quite who was what and why. Ripley does not emphasise them because he is holding them for the denouement, that much I could see, but still…. Nonetheless I felt cheated.

As usual I found Campion all too much like one of my college roommates who loved the sound of his own voice twenty-four hours at a time. Does Campion ever breathe one might ask, such is the lava flow of words. And it is that bright young thing sort of tosh favoured in the 1920s by insouciant young men who had a right to such absurd irreverence, having survived the trenches. Albert has no such warrant.

What I liked was the representation of life in Vichy France around Mentone and Nice where the story started, though the scene shifted all too soon to Marseille and that big city is like other big cities, whereas Mentone and Nice are different, as much Italian as French with the Alps on one side and the sea on the other. (Plus I have been to both Mentone and Nice.)

The insularity of the British of a certain age and outlook is also nicely done. Well, overdone, but still, shades of Captain Hastings, it is tasty.

The plot about the book-keeper stuck me as farfetched but that is what fiction is.

Nothing competes with J. Robert Janes accounts of life under Vichy in his numerous books, but the key one in this context is ‘Flykiller’ (2002).

Many Krimiologist will remember Margery Allingham well. She penned about twenty novels featuring the supercilious and verbose Albert Campion, who seemingly never got to the point but did somehow. These were set mostly between the Wars, as used to be said. (Readers who do not know which wars are invited at this point to click away, and stay …. away.) As with Agatha Christie and others, her character — the annoying but somehow tolerable Albert Campion — has outlived her. By the legerdemain of a literary executor, since Allingham’s death, he has had further adventures written by Phillip Carter (Allingham’s widower) and he in turn brought the talented Mr Ripley into the fold. This is the fifth title from the Ripley keyboard. The novel is well written and has a nice premise in Vichy. But Campion can be taken only in small doses. Might try one of Ripley’s other krimis. Did so. No sale.

Allingham also wrote ‘The Oaken Heart‘ (1941) when a German invasion was expected any day on the Essex coast and she and her neighbours would be on the front line.

Here she is at home about that time.

Here she is at home about that time.

That will be on my reading list.

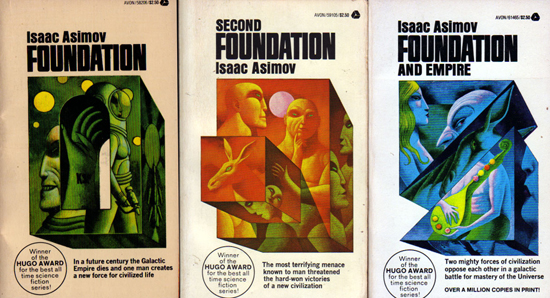

‘The Foundation Trilogy’ (Audible) by Isaac Asimov

Asimov began publishing the stories that comprise this work in 1942, leading to the original three volumes: ‘Foundation’ (1951), ‘Foundation and Empire’ (1952), and ‘Second Foundation’ (1953). Each has about 250 pages. In this rendering they are Readers-Digest condensed and dramatised with a cast of superb players including Maurice Denham, Julian Glover, Dinsdale Landon, Angela Pleasence, and Prunella Scales. It was broadcast on the BBC in 1973.

All in all it is well done. Indeed I was sorry when we got (back) to Star’s End.

It all begins with Professor Dr Hari Seldon on planet Trantor doing macro-mathematical modelling. Using the vast body of data accumulated over the thousands of years of the Empire, he devised a way to predict the future – psychohistory. There in his study, meeting his KPIs, engaging in 360-degree reviews, refereeing papers, submitting to peer review, attending training courses, being tutored for the latest management fad, sitting on selection, tenure, and promotion committees, figuring out how to log into Publons, making endless applications for ever smaller grants, mindful always to keep his door open when female students enter no matter how confidential the discussion may be, complying with Occupational Health and Safety standards in the work place for the data assistants, writing a stream of letters of recommendation for colleagues re-applying for the jobs they have been doing well for years, meeting the fathomless demands of the Ethics Office, he foresees catastrophe.

No one wants to hear bad news, least of all Mahogany Row at Streeling University where Hari ekes out his days as above. For his trouble he dies at his desk, with a funding application incomplete. He failed to meet the last KPI.

Wait! Seldon had long given up on the authorities, educational, political, and religious, and made his own plans. The catastrophe was certain and unavoidable, the Empire would fall into corruption and a period of barbarism — promoted by Pox News and led by President Tiny — would follow. The knowledge of climate change, vaccines, idiocy eradication, and more, that would be lost in a few hundred years would take many thousands to develop anew. It stays dark a long time in a Dark Age, leaving aside, far aside, the scholarly quibbles about the definition of ‘Dark.’

While the collapse was certain, the period of subsequent barbarism might be abridged, and this abridgement became Hari’s purpose, one well concealed since it did not meet his KPIs which were focussed exclusively on next year’s grant round. He created sub rosa a Foundation on the mud heap of Terminus with the purpose of creating a Galactic Encyclopaedia that codified existing knowledge so that when the Empire collapsed there would be the technical and intellectual resources to begin re-building civilisation at a faster rate than otherwise would have been the case. Or maybe not.

He worked out the Seldon Plan (see the entry in Wikipedia) according to which the knowledge within the Encyclopaedia would be put to work. In projecting the future, Hari realised that there would be crises which would be turning points in the tree diagram when the felt tip whiteboard marker he was using run dry. These were Seldon Crises while he looked for another felt tip. He left time capsules with instruction to deal with five of these.

Sure enough, the Empire collapsed, imperial over-reach and too much McKinsey mis-management. Chaos, anarchy, confusion, all the hallmarks of a Republican administration appeared. In dark times one ray of hope was the rumour of the Foundation. Some want to destroy it so that the GOP can reign supreme on the way to Hell. Others look to it for salvation on the way to Heaven.

The Foundation used its store of technical knowledge to conceal itself, defend itself, and to assert itself to restore order. But was the Foundation immune to the idiocy that destroyed the Empire. Did Seldon foresee that, too.

Rumours circulate that there is Sequel Foundation; Second Foundation to give its prosaic name.

This vaporous Second Foundation is located at Star’s End, or is that Stars’ End, or even Stars End? Tricky. And what does it have, if not technical knowledge? Cookie recipes?

The master narrative is free will versus determinism. The Seldon Plan maps the future, but for that map to become reality individuals have to act. Can idiographic events derail the nomothetic path that Seldon laid out? Huh? Well, can unpredictable events upset the plan? The Seldon Plan operates at the highest level of social abstraction of whole worlds and interstellar cultures, not single events, like a jealous husband slaying the emperor, or the mutant Mule arising. Or President Tiny making sense for once. (Still waiting for that last one.)

The future is a script with many blank pages, said the Brazilian political scientist Robert Unger, making so much more sense in one line than Anthony Giddens made in a dozen books on the same subject, or was that one book re-utterated eleven times.

Hence most of Hari’s holographic time capsules are pep talks about doing the job.

If Asimov had heard McKinsey speak he would be made the most of it. Much can be said in it and nothing said at all at the same time. See any Dilbert cartoon for illustrations.

Asimov in the 1940s before the sideburns took over.

Asimov in the 1940s before the sideburns took over.

The story has the strengths and weakness of any Asimov fiction. The sweep of events and action are fine, the science is sound, but the characterisations are cardboard, despite the efforts of the actors. They have no inner being.

Liberties were taken to cut the 756 pages of three books combined into seven hours of broadcast. These abridgements have infuriated some who have commented on the Audible page. The compensation, which escaped most of these leg biters, is the acting. Though that, too, is derided by some who must have been in dental chairs when they listened.

There is one thing we all agree on —‘It’s time for lunch,’ cried the fraternity brothers! — no. The transitions from one scene to another are far too loud, too long, too annoying, too distracting, too loud, and too loud, worse than commercials on television. For once I agree with something a whinger wrote on the Audible comments page. Circle this day on the calendar because it is not likely to happen again.

Stefan Zweig, ‘Chess Story’ (‘The Royal Game’) (1941)

Genre: Fiction, a novella

GoodReads meta-data is 104 pages, rated 4.3 by 47798 litizens

Verdict: Bleak

On a passenger ship from Europe the world chess Champion struts. After being offered a cash inducement, he agrees to play a group of passengers co-operating as a single opponent. They have nothing in common but an interest in the game and bragging rights about being beaten by the Champion. He treats them and the games they play with contempt.

Then one day in the game room for the daily humiliation, while they argue over a move, a passer-by makes a suggestion, and then another, and another. This Stranger seems to see far ahead in the game and a stalemate ensues. All are amazed, especially Champion, who however pretends to have let them draw when in fact after the Stranger’s intervention he had no way to win.

Observer questions Stranger and finds he was a victim of the Naziis who kept such sanity as he had by playing mental chess against himself for years of confinement.

Champion knows nothing but chess and is presented as some kind of idiot savant, while Stranger is an obsessive who is consuming himself. Neither is a recommendation for the game.

As is to be expected the novel starts with endgame, and moves back through opening and mid-game. There is a lot of K B-7 in it.

We saw a performance of his play ‘Beware of Pity’ and that together with our putative trip to Vienna led me to read this novella. Zweig was living in exile in Brazil when he wrote it and committed suicide shortly after this was published. Were the reviews that bad? Or was the Viennese fetish for suicide in the gene pool.

I am not inclined to seek out more Zweig. Too bleak for this good time boy.

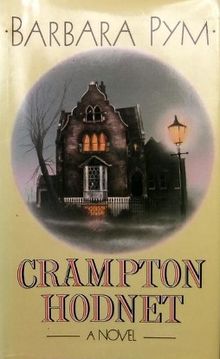

Barbara Pym, ‘Crampton Hodnet’ (1940)

Genre: fiction

Goodreads meta-data is 216 pages rated 4.01 by 1542 litizens.

Verdict: Nothing happens and it is fascinating.

In North Oxford Miss Doggett rules the house with an iron fist in an iron glove. Her paid, but not very much, companion Miss Morrow observes life with a quiet inner smile, having learned well how to steer around Miss Doggett who does not pay her to smile.

Miss Doggett invites the new bachelor curate to lodge with them, and makes a fuss over him, expecting in return to be fussed over, too, but no. Strangely he finds the enigmatic, grey, mousy Miss Morrow of more interest. Quietly infuriated, Doggett casts around for the means to bring the curate to his senses, dimly aware that Morrow is the problem. While amused by the curate’s attention, Morrow wisely knows it will go nowhere, which it does, slowly.

Meanwhile Francis Cleveland, an irascible scholar at Randolph College in mighty Oxford University contemplates an affair with one of his students who looks at him adoringly when he recites poetry. She is flattered by his attention, until she realises his intentions! Such thoughts provide yet another in a long list of excuses for Cleveland not to do any work, and he doesn’t. In the great tradition of the English novel, including C.P. Snow, Oxbridge dons do nothing and do it very pompously. Bring on the Research Quality Framework!

There are comings and goings involving these two pairs of near-paramours, and the gossip that sightings of them kindle takes fire. Miss Doggett is there with kerosine to make sure that rectitude is rectified.

In one of the standard tropes of the era, several of the characters go off to Paris and return, chastened, once more to their routines. The curate finds a more fitting object of his desire. It is low key but so very human and humane in its delineation of character.

Pym wrote the manuscript very early in her career and it seems to have got shelved by the events of World War II and remained unpublished until 1985.

While the GoodReads rating is, for once, something that chimes with me, the summary is mistaken.

Paul Thomas, ‘Fallout’ (2014)

Genre: krimi

Goodreads meta-data 272 pages, rated 3.7 by 80 litizens.

Verdict: The satire has become sanctimonious.

Maori detective Tito Ihaka is assigned a cold case by the Commissioner, who is nearing retirement and would like this one cleared up because it was the Commissioner’s first murder case many years ago and he failed to resolve it. Now he puts the impossible and impossible to stop Ihaka on the impossible case. Done right that would be enough material for the novel.

However, we have a parallel development when Ihaka learns that his father’s death years ago, attributed to a heart attack, may have been murder.

There is indeed a parallel of sorts. Ihaka finds the nouveau riche involved in the cold case a tiresome set of villains and he finds the ardent trade unionists involved in his father’s death a tiresome set of villains. I agreed on both counts: tiresome.

All the usual clichés are present, an obstructive superior, a dysfunctional home life, lying witnesses, bossy civilians, duplicitous politicians…. Nary a breath of fresh air is to be found among these clichés.

It seems, like Christopher Foyle, Ihaka is the only just man.

Paul Thomas

Paul Thomas

I have read the first three titles in this series chronicling the investigations of Tito Ihaka in New Zealand, and I found the early titles to be whip-smart without the preaching in these pages: ‘Old School Tie’ (1994), ‘Inside Dope’ (1995), and ‘Guerrilla Season’ (1996). But in this one — written long after the previous title in the series — Thomas seems to be engaging in some social criticism about the nouveau riche or something, and nearly every page consists of backstories. The result is that movement, action, scene, development are absent. It was like reading the notes for a novel, but not the novel itself.

Robert Harris, ‘Cicero Trilogy: Imperium (2006), Lustrum (2009), and Dictator (2015).’

Genre: fiction, biography

GoodReads meta-data is, in the order listed above, 496, 452, and 544 pages, totalling 1,492 pages, the trilogy as a whole is rated 4.6 by 308 litizens. Each of the separate titles has an entry on GoodReads, as well, with a separate rating for detail hunters.

Verdict: Robert Harris is a genius at such historical fiction.

‘What nation has ever erected a statue to a man because he was rich?’ Sorry Clive Palmer but there it is.

‘A home without books is a body without a soul.’

For reasons only known to the high priests of publishing, the separate novels have different titles in the USA and UK editions to confuse librarians, readers, and buyers. Beware.

The three titles of this trilogy offer the reader an eye witness to the long fallout of the Roman Republic as experienced by Tiro, slave to Cicero. The author’s premise is that long after the events, Tiro wrote down what he saw and heard, making use of the extensive notes he had taken along the way, as well as his prodigious memory. The result is a biography of Cicero in all but name. Well, I read it that way.

Tiro was Cicero’s confidential secretary and they were seldom apart in waking hours for forty years. Cicero had a mania for detail and wherever he went, Tiro was there to take notes of everything said by Cicero and others. These notes were possible because Tiro had devised a shorthand notation that allowed him to keep pace with even the most garrulous speakers. Tiro is credited with the ampersand ‘&’, the abbreviations etc, NB, i.e., e.g., and much more. Xenophon had some primitive version of shorthand nearly four centuries earlier but none of it survives. He used it for notes on his campaigns.

Tiro’s written records were a novelty and it often gave Cicero an edge against his numerous opponents, rivals, and fellow travellers. Tiro’s perspective allows the author some distance from the subject, while making clear Cicero’s towering achievements, his errors, foibles, and lapses are there to see.

Cicero was a wordsmith and much of the novel takes the form of dialogue and even speeches, yet it is so well judged that it does not seem wordy, nor does the pace slow, despite the verbiage.

Other intellectuals like Thomas More, Niccòlo Machiavelli, Alexis de Tocqueville, John Stuart Mill, and Max Weber, all had political careers, but none of theirs was anything like Cicero’s. A country bumpkin, he rose steadily with ambition and ability in the Roman Republic. HIs rise is the more remarkable for his disinterest in the sword and his lack of money, normally the keys to success. What he had in plenty was words with which he often found a high ground unseen by others quick to the sword or awash in money.

His legions were his words, and by them he rose and survived, often against the odds, and occasionally cut down his enemies. If he finally lost to the sword at sixty-two he mused that having lost the past and the present, his words might still win the future: the judgement of history. In that he was right. We know him, his words, and his fame but those of few of his many enemies.

He also became a household name then and now, sort of. Great oratory, like great poetry or music, is a distillation of emotion into an exact form. But to convince other he himself had to be convinced, and part of the story here is how he convinced himself of this course or action and that, sometimes in contradiction to one to the other.

He was neither a demagogue nor a patrician, but at times allied with each. At times one faction used him and at other times he used that faction. He steered toward the best interest of Roman, and that chiefly was stability without civil war and with civic freedom. His incessant search for a compromise brings to mind another orator, Henry Clay. In his flexility in trimming to steer to the distant shore of peace he likewise brings to mind another Kentuckian, Abraham Lincoln. Cicero had few principles but he had a goal that determined his method.

Seeking stability meant making strange bedfellows, and changing them from time to time. Patronage, when he had it, was used to divide and confuse enemies, not to reward friends, and later that tactic cost him friends.

He lacked the consistency so loved by the simple-minded of journalism. The straight line is seldom the shortest way between the here-and-now and peace in the world of politics.

He revelled in the political world: ‘Politics is history on the wing! What other sphere of human activity calls forth all that is most noble in men’s souls, and all that is most base?’ Hmm, well most major sports now fit that bill but….

The best analogy for statesmanship in Cicero’s opinion is ‘navigation – now you use the oars and now you sail, now you run before a wind and now you tack into it, now you catch a tide and now you ride it out. ‘Just as the purpose of a pilot is to ensure a smooth passage for his ship, and of a doctor to make his patient healthy, so the statesman’s objective must be the happiness of his country. One merely adapts to circumstances as they arise.’ Navigating politics takes years of skill and study, not some manual written by a deep thinker.

Into the mix of the Roman Republic came a lightning bolt named Julies Caesar wearing the mask of a wastrel while scheming for an even bigger prize than Cicero ever imagined. And the rest is history….

Cicero succeeded beyond his wildest dreams but his cursus honorum to success left many discarded allies, out-distanced rivals, and bred in the bone enemies, and with success Cicero changed, became complacent, over confident, and even, surprisingly for this restless man, lazy. Meanwhile, his enemies accumulated. In semi-retirement he was no longer a player but he was a symbol that those enemies, some of them patricians and others plebeians, could use to arouse followers, the discarded allies and the beaten rivals.

Then the final rupture came and he came back into a no-win situation where this wily old fox was outwitted by a gangling teenager called Octavian.

Among the vast cast of characters there is the anti-Cicero, namely Cato, who lived like a pauper, despite his great wealth, and embodied his uncompromising Stoic philosophy. When he learned that Caesar would arrive the next day he did as he advised others to do: he bathed, dined, read philosophy, and then fell on his sword to commit suicide. N.B. Cato did not bathe often and seldom ate more a few olives.

The history is well known and Harris takes some liberties with it to make a coherent story seen from Tiro’s point of view by occasionally back-filling. In lesser hands these occasions would have seemed intrusive and didactic but not so here. There is also some fiction in this work of fiction.

A patient reader finds many rewards in the descriptions of the time and place, and in Cicero’s insights into the world of Roman politics. Here is a sample of Cicero’s perspective on Roman democracy, such as it was. ‘You can always spot a fool, for he is the man who will tell you he knows who is going to win an election — an election is a living thing – you might almost say, the most vigorously alive thing there is – with thousands upon thousands of brains and limbs and eyes and thoughts and desires, and it will wriggle and turn and run off in directions no one ever predicted.’ And that living zoological aspect of elections is what Cicero found so fascinating. He added that elections in the end were ’perhaps one of the things that killed the republic: it gorged itself to death on votes.’

Or consider his remarks on history: ‘To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always a child. For what is the worth of human life, unless it is woven into the life of our ancestors by the records of history?’

Those readers who know these Romans and these times through Shakespeare and the many derivations from the Bard, will find a harder and darker reality in these pages. Shakespeare, too, took liberties for his purposes, because he was not writing history. That is fine, the problem is some naive readers take it that way, as the same naive viewers take a film like ‘Dunkirk’ (2016) to be history when it certainly is not.

It is one of ironies of fate that most of Cicero’s many books are lost, destroyed in the debacle of the fall of the Roman Republic and then the divisions and destruction of the Roman Empire. While Plato’s works, five hundred years earlier, survived, having been widely disseminated before the collapse of the Greek world.

I have never managed to read more than a few pages of Cicero. I found him a high context writer and I did not have the context. I have looking for the copies I have on the shelf, and maybe…. My favourite Roman from this period is Decius Caecillus Metellus the Younger, who does not appear in Harris’s pages, but in the pages of the escapists series of krimis by John Maddox Roberts.

‘The Singing Masons’ (1950) by Francis Vivian and ‘Beekeeper ‘(1999) by J. Robert Janes

‘The Singing Masons’ (1950) by Francis Vivian

GoodReads meta-dat is 226 pages, rated 4.25 by 4 litizens

‘Beekeeper ‘(1999) by J. Robert Janes

GoodReads meta-data is 305 pages, rated 3.96 by 28 litizens

Verdict: Beeology galore.

In ‘The Singing Masons’ the local playboy is found at the bottom of a well. Scotland Yard dispatches Inspector Knollis to the small town of Cleverly to get to the bottom of things. (Groan.) He does.

Nobody has a good word to say about the deceased, not his fiancee, not colleagues at work, not his many conquests, not his landlord, not his cousin, not anyone. Moreover, as investigation continues it seems Playboy was up to some shenanigans of his own, burning down the property of a romantic rival, and planning to murder his fiancee as soon as they were married so he could inherit and move on. Like a good stereotype, there was no end to his perfidy.

The manners and mores are rural England of the 1950s. I expected my crush Flavia to show up at any moment on her bicycle Gladys and sort things out with her chemicals. No such luck.

This is a puzzle krimi in the manner of the Queen of Crime, Agatha Christie. All the information is there for the reader to detect the villain and in due course, after repeated, and I mean repeated, interrogations the plod do detect the villain, who was obvious from page one to hardened krimiologists.

I chose to start with this, the sixth, volume in the Knollis series because I have been reading about bees in several books discussed elsewhere on this blog. There is much lore about bees, and in the end the bees are well integrated into the story throughout and decisive in the plot.

While in the literary apiary I also re-read Janes’s ‘Beekeeper.’ This is the eleventh in his series. He sustains the an atmosphere like few others. It is winter in Occupied Paris, January 1943. There is no fuel for heating. No energy for lighting. Little food. The Occupier is everywhere.

A beekeeper is found poisoned and St Cyr and Kohler, that odd couple, are assigned the case. It is dark and tangled world of black market, rapacious Naziis, rivalries among rapacious Naziis, bitter priests who have been displaced by the Occupier, the shadowy resistance, and the sheer struggle to survive.

The fact at the bottom of the mystery is that one of the evils of Naziism was the wholesale destruction of beekeeping in Russia. In rear areas, apiaries were systematically looted with the hives piled on railway cars and send to Paris, where there was a thriving market for beeswax candles (since no electricity was available any longer, and moreover churches had to have beeswaax candles). Thousands and thousands of hives, and in them came a bee virus that began to infect French bees.

The beekeeper had found this out and was about to tell all. Is that why he was poisoned? Or was it because his wife hated him for rejecting her son by another marriage? Or was it the animus of childhood friends whom he had blackmailed for years? Or the local priest who might suppose the flock would be more stable without this volatile man around? Or did the alienated step-son do it? Or was it a supremo of the black market? Or the German importing the hives? Or…. Or was the poison intended for someone else entirely?

I admit at the end I was not quite sure what the answer was, but the trip, as always in these stories was engrossing..