GoodReads meta-data is 489 pages, rated 3.3 by 43 litizens

Genre: Non-Fiction

Verdict: Journalism.

N.B. I listened to it in an Audible reading. On that more later.

‘The Nobel Prize.’ Words that command respect far and wide. There are many prizes in many fields, then there is the Nobel Prize. Its origin and history is as interesting as its many recipients. More than 700 Nobel Prizes have been awarded since 1901.

Father Nobel was a Russian tinker, mechanic, and inventor who moved west, first to Finland, and then to Sweden. He took the name ‘Nobel’ in reference to the village in Russia from which he came. Father moved around a lot and experimented with explosives, which made him unpopular with many a landlord.

Alfred (1833 -1896) learned technical skills from his father, and he also learned the relevance of different jurisdictions for patents and copyrights. His two brothers went back to Russia and made enormous fortunes in oil. They were styled the Russian Rockefellers until the Reds came.

Alfred followed in his father’s footsteps literally and figuratively. He experimented with explosives and he traveled to and fro in Western Europe. He was polyglot from an early age, starting with Swedish and Russian, and later French and English.

His breakthrough was to control nitroglycerin which had been developed a generation before but had proven too volatile to be used. By trial and [kaboom] error he learned to soak it into a substance like sawdust and pack it into sticks. There followed the detonator.

He was careful to copyright and patent everything in every jurisdiction. He set up factories to produce his wares which far exceeded gunpowder in both explosive power and the capacity to be controlled in small doses. Typically he worked with local partners and was often content with the return from the intellectual property and a minority interest of 25-40%. He left management to these others.

Without TNT, let’s call it for short, the Suez Canal, the Brenner Pass, the Panama Canal, the great excavations for city subways might not have been possible. Nor would mining have unleashed copper, iron, and minerals as readily.

A given quantity of TNT had twenty times the explosive power of a like amount of gunpowder and it was also quickly converted into a weapon of war, and even in his lifetime Nobel was denounced as a merchant of death. That bothered and bedevilled him.

Nobel moved around, though he spent most of his time in France and seldom returned to Sweden after nine years of age. He never married and there is little hint of romance, sex, or marriage. He had a touch of the gloomy manner of a Swedish stereotype and became preoccupied with his will at a relatively young age.

In the last three drafts of his will he proposed prizes to recognize, honour, and reward those who had recently benefited idealistically humanity. Each of those adjectives became the subject of interpretation He added and subtracted prizes over the drafts.

The Peace Prize came late and is attributed to the influence of a woman friend. The terms ‘Peace’ came into being later. He referred to it as a prize to someone who done the most to avert and eliminate war.

The will named executors whom he had not consulted and who barely knew him. They were surprised and bewildered by the task. The will made no allowance for the expenses necessary to set up and establish the prizes funded by the interest from the bequest. Moreover, the will was disputed.

Distant relatives — cousins, nieces, nephews — all challenged the will. Nobel had written his will out in a letter without consulting a lawyer and so it was vague and devoid of legal formalities which encouraged challenges.

In addition, the sum of money was so great that the Academie Française argued that Nobel was French by residence and that the bequest should be established in France to be managed by …. [go on guess].

Only when the Swedish government intervened did the matter resolve itself, some five years after Nobel’s death. Even so there was little support for the wherewithal to create a permanent organisation and the Swedish government only slowly funded that. However, by insuring that the huge Nobel fortune was invested mainly in Sweden, stimulated the government to pay the upkeep for an office, heating for the rooms, postal charges, salaries for clerks and hotel bills for experts to make selections.

Nobel had also left instructions, albeit vague, about how the money was to be invested to produce an income for the prizes, and this, too, was challenged. The sum was so great that its investment in Sweden did much to boast Sweden into industrial competition with Germany, England, and France, despite being so much smaller. Those famous Swedish industrial names were in some part seeded by Nobel funds, i.e., Asko, Bophors, Electrolux, Ericsson, Kockums, Saab, Skanska, Volvo, and others.

Managing such a fund also gave the Bank of Sweden an international profile and experience that contributed later to its role in administering the Marshall Plan, which in turn gave Sweden a disproportionate role in post World War II diplomacy; an example is Dag Hammarskjold, a one time employee of that bank and administrator in the Marshall Plan. A biography of Hammarskjold is discussed elsewhere on this blog.

The impact of the Nobel Prize on Sweden was manifold. varied, and enduring. It also put Swedish scientists in the main stream of current research, and served as an entree into world scientific establishments. While scientists in comparable countries like Norway, Spain, or Italy were ignored, the Swedes were feted, and still are.

However the author is more interested in muckraking over the choice of recipients than in these long term financial, economic, social, and political dimensions.

The first substantial chapter concerns the literature prize. This was close to Nobel’s heart for he wrote plays and poetry in English and was an avaricious reader in several languages. The author points out some of the second-rate recipients of the Nobel Prize for Literature, especially in the early years when the process was inchoate, and that giants overlooked.

But the author makes no argument that these greats could have been selected. ‘Should have,’ yes. But ‘could have?’ There is only one prize a year, and even eliminating the second-raters, there would not be enough prizes for all the those omissions recited by the author. Indeed much of the book is lists of names that seems like a telephone book when listening.

While once I made it a point to read something by Nobelist in literature, no more. To this casual observer of late the Nobel Prize in Literature invariably goes to writers I have never heard of and do not want to do so. No doubt that attitude condemns me in the eyes of some. But criteria that are implicit in some the author’s fulminating are extent and durability. And I suspect many of the recipients in the last generation will not pass either test despite the lustre of the Nobel Prize.

The author also criticises the Nobel for not comprehensively covering all the literatures in all the languages in the world. This tirade is carried on and on. This auditor began to think even unpublished works would have to be canvassed to satisfy the divine criterion the author applied.

Perhaps the world’s greatest poet, composed poems on pages, which were then kept under a rock and never read by another, let alone published. The author seems to think that omitting such works undermines the prestige of the Nobel.

I blandly used the term ‘second-raters’ above to move the discussion along but reading the comments on novels on Good Reads leads me to conclude that any ostensible second-rater would have many ardent defenders. On Good Reads I have seen some of the most inane and pathetic novels stoutly defended by self-appointed champions, some of whom can spell.

Nobel specified that the Peace Prize be given by the Norwegian parliament in the recently independent Norway. This, too, was contested. Swedes had (still have but are less vocal about it) a low opinion of those truculent Norwegians, and regarded Oslo as the Nordic equivalent of a banana republic. Efforts were made to rescind that provision but international pressure and the distractions of the rest of the bequest preoccupied the Swedes and they let the Norwegians off the hook.

The author blandly assumes that identifying great works in the sciences is easier than in literature. He repeats that comment at the end of the book but when reviewing the science prizes he notes the faked results, cronyism, blinding ambition, citation clubs, organised national efforts to corral a prize. He notes the unintended consequences of science Nobel awards in distorting research agendas, either to get a Nobel or to follow in the wake of one. On this point I wished for more.

The author certainly makes clear that Nobel Prizes have became a major industry in Stockholm. It involves many committees, institutions, institutes, translators, evaluators, nominators, assessors, advisors, diplomats, clerks, managers, administrators, tech heads, and more. The activity is continuous and involves, offices, telephones, email, computer systems, a massive archive to be made digital, postage, travel, hotels, and more. All of this is done in absolute secrecy and so there is no way to estimate the cost in a year.

Secrecy is the order of the day for Nobels and it has been kept surprisingly well. I say surprisingly because leaks are the order of most days anywhere else. I would have liked some consideration given to why the rule of secrecy has been so successful there, when it is so seldom successful say for cabinet meetings, corporate boards, and examiner’s committees. For these latter meetings the secret results are usually broadcast before the written record is completed. Casual visitors to most Western European capital cities will be told state secrets within hours. The business pages spill the beans on secret corporate board meetings every Friday it seems.

I heard nothing about the origin of the Economics prize though the author spends some time in disparaging its recipients. As a layman, it seems he knows the worth of the work involved. He would not have ventured such remarks about physiology, I suspect. By the way, when I was Associate Dean in the Faculty of Economics I received a nominating form each year. I did not do so. But that fact indicates the massive mailing done.

Likewise I missed the chapter on the Peace Prize. Ergo I can give free rein to my spleen that Al Gore got one for being an insider and Barack Obama who got one for not being George Bush. Maybe he should not get another for not being President Tiny.

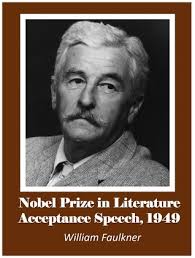

After years of Nobel Watching (think Kremlin Watching) the Nobel Foundation released the archives for the first fifty years. The author has great fun trolling through those for example of idiocy which can be found. While he acknowledges the daring on the part of the Nobel officials, say in making an award to William Faulkner in 1949 when his books were out of print and he was dismissed by such arbiters of opinion as the ‘New York Times’ as a village idiot. He does not go into the details of such selections but concentrates on omissions, like that of Joseph Conrad. Yes, Conrad was a great writer equal to any Nobel Prize winner, I agree.

However to get back to the view from my high horse, I also find that the author makes few, very few references to the acceptance speeches. Yet some of these in literature are even more remarkable than the works that secured the Prize. Faulkner’s ‘De Profundis’ is diamond bright.

Many questioned John Steinbeck’s stature, yet his acceptance speech burns with celestial fire. That the citation written by the Committee that selected him includes some inanities hardly diminishes Steinbeck’s work, though the author makes a meal of them. My point is not that an acceptance speech justifies post hoc an award, but rather than the acceptance speeches are part of the whole process of the Nobel and have a place in its history.

Many questions remain. How many people does the Nobel Foundation employ, full or part time? What role does the Swedish diplomatic corps play in facilitating the process? These remain known unknowns. How has the process changed with chaining technology? What kind of lobbying for prizes goes on? No single work could comprehend the whole, and perhaps there are others that have considered these questions waiting for me.

Above I noted that I had not heard this or that. Listening to it while walking or at the gym means some things get by me, and perhaps that in handling the device there are skips. This is hard to check without a table to contents with chapter titles.

The reading was staccato and grew ever more irritating. The prose was continuous but the reader imposed a staccato rhythm to it that made it sound like a breathless reporter from the rooftop. That made me reluctant at times to continue. No doubt on the Audible web site, there will be fans who loved that Hemingway drill delivery. Not me.

Category: Book Review

‘Archangel’ (1998) by Robert Harris

Good Reads meta-data is 432 pages rated 3.8 from 7906 litizens.

Genre: Fiction

Verdict: Meticulous and engrossing.

Soviet historian Robert Kelso delivers a keynote address at a conference in Moscow circa 1996. He is jaded; he is cynical; he is bored; he is a high diver. He graduated from the best universities and published well-reviewed books and then….. He went from a promising young man to a bitter middle aged one. Still the conference sponsor paid his way to Moscow and put him up in a posh hotel to make snide remarks about the work of others, so there he is.

Then a blast from the past knocks on his hotel room door. Not his past but the P A S T. Papu was one of the lowly guards when Stalin died and he says there was this notebook. In return for all the alcohol in the hotel room mini-bar Papu tells Kelso the notebook was buried in the grounds so explosive was its contents. After his middle-aged bladder takes Kelso to the toilet he returns to find Papu gone.

In the haze of a hangover the next morning, Kelso sees in this story an opportunity to jump start his stalled career. He will find Stalin’s testament, translate it, interpret it, publish it and return to the fast track of the main game.

There are a couple of problems to deal with. First is finding Papu. Second is funding anything since his personal credit cards are maxed. Third, he is not good at keeping things to himself.

Still Papu could almost be followed by his body odour. Meanwhile, Kelso tries to verify aspects of his story with some library and archival research which he used to be good at, which he used to enjoy, which he still knows how to do. But merely by consulting the sources, he leaves a trail were anyone watching, and in Russia there is always someone watching.

He crosses paths with a dedicated Old Stalinist who scares him. Indeed this Stalinist seems to have his own army. He is purposeful, organised, efficient, and surrounded by dedicated followers.

Then a journalist enters the equation. Talk about loose lips. This guy cannot shut up. Soon every one is after that testament. Even the vodka-soaked President in the Kremlin, Boris, wants it, and sends a hapless secret policemen after it in competition with the Stalinist, the historian, the journalist, and who knows who else. It is not a secret well kept.

The trail leads north to the title city, and in the forests primeval there Kelso and the others find much more than they bargained for. It was a testament alright, but not the kind most of them had anticipated. Let’s just say it harks back to an earlier, passing remark about Trokhym Denysovych Lysenko.

I liked the portrayal of the ever so polite academic backbiting at the conference for its realism. The characterisations of all the players were superb from the law student daughter to the crazed Stalinist and the dutiful secret policeman who discovers that the water is far too deep even for him, and most of all the bullies from Special Operations (code for Death Squad). I also liked the archival and library work. Strange, no?

I also liked the idea that the Stalinist was the puppet master using the avaricious journalist, Kelso, and others for his own ends from the get-go.

But I am not sure what to make of the implicit ending. Would a Marakov really settle things?

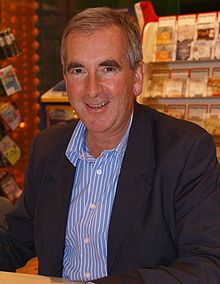

Robert Harris has a long list of splendid novels based on historical incidents.

I am pretty sure I read this at the time of publication but none of it came back while it read on the Kindle.

‘An Officer and a Spy’ (2014) by Robert Harris

Good Reads meta-data is 429 pages, rated 4.2 by 17,737 litizens.

Genre: Novel

Verdict: An incredible story well told.

This is a novel about the l’affaire Dreyfus of 1894 in which the blameless Alfred Dreyfus (1859–1935) spent five years in solitary confinement on Devil’s Island in a prison built especially for him. His punishment took many additional forms. Were that not enough he spent another five years in a mainland prison.

His crime was to be Jewish. The accusation was that he had given military secrets to the Hun. It was but a generation since the humiliating French defeat in the War of 1870 by Prussia and the Hun was detested.

That detestation was crucial because Dreyfus’s second crime was to be from Alsace. When Alsace was ceded to Prussia at the end of the war, the population had to choose. Stay and be German, or be French and evacuate. His family chose to be French and left Alsace. In the convolutions that followed this choice was taken as evidence that he was a sleeper agent of some sort.

His third crime was to be well off, and not dependent on his army income as a captain. This made fellow officers envy him, ready and willing to be believe the worst of him to explain why he had money and they did not.

The fourth and most significant crime was to refuse to confess to something he did not do to shield the honour of the army. Its incompetence and stupidity certainly needed shielding.

It began with a scrap of paper purloined from the German embassy in Paris. It had been torn into bits and when it was pieced together the inference from it was that it referred to the passing of French General Staff secrets to the Germans.

Two questions arouse immediately. First, who could have done this deed. The second was who would do this. It could have been done only by an officer with access to the General Staff files. It would be done by a Jew. Dreyfus met both criteria. Guilty! (At times it was also alleged that as an Alsatian of German descent he was loyal to Germany. That second order point was used to explain his motivation since no money seems to have changed hand, and he did not need it. But Jews betray because it is in their blood.)

Once he had been identified no further investigation occurred. Rather all energy went into convicting and punishing him. A very great deal of expense went into his punishment by creating a prison for him alone on the otherwise uninhabited Devil’s Island near Cayenne.

Later a French counter-intelligence officer stumbled on a loose end and began to tug on it. The wagons went into a circle and the cover-up became more and more extensive and intense. An effort was made to send this officer, who just would not let it go, on a suicide mission in North Africa, but his local commander stalled that. The officer’s determination was painted as an effort to discredit the army, not to see justice done to Dreyfus, or, by the way, to apprehend the real villain who was still at large and still selling.

All in all it makes Watergate seem like a student prank.

The organisational pathologies of the army bureaucracy are mercilessly dissected in these pages. While senior officers plotted against each other for promotion, they united against outsiders who might disturb the playing field on which they schemed against each other.

There was no big bang to clear Dreyfus but a numbing series of re-trials, appeals, inquiries, and more that gradually eroded the conspiracy of the cover-up. The conspirators had to prop up the lies for ten years in both military, civil, legal, and popular arenas and in so doing they made mistakes. It is hard keeping a tissue of lies straight. The truth began to leak out, drop by drop.

But a quick spin around web sites indicates that there are today plenty contemporary nut jobs, when they take time off from denying the Holocaust, who proclaim Dreyfus’s guilt. President Tiny would doubtless declare them good people.

It is implied in these pages that at least two weak links in the cover-up were murdered as cut-outs. Certainly many involved with the matter died prematurely. Others went into voluntary exile. One lawyer for Dreyfus was shot on the way to the court and the presiding judge refused a recess to allow the defence to reorganise. A great many junior officers were suborned into lies and calumny to protect their superiors.

Only in 1906 was Dreyfus exonerated and restored to rank. Likewise the counter-intelligence officer who himself had been imprisoned was restored to rank and promoted. Both served in the Great War, 1914-1918.

I never did fathom who was responsible for the two murders. The shooting of the lawyer was perhaps a self-appointed fanatic. Although, maybe not.

Nor did I ever did fathom the behaviour of the real wannabe spy, the dissolute and brazen Ferdinand Esterhazy.

Finally, I could not quite understand how so many junior officers were suborned into the cover up with nary a leak. Suborning I get but without a leak? That part I don’t.

I do not doubt that these things happened but the novel sheds no light on them.

In keeping with the whole sad spectacle most of the original evidence has since disappeared, says the Wikipedia entry. That word ‘disappeared’ would be a euphemism for the word ‘destroyed.’ There is no longer any bottom to touch.

While I am picking nits the novel is written in the first person singular in the present tense, and I almost stopped reading it on page five because of that. Only my experience with reading and valuing previous novels by Robert Harris kept me at it, though on every page I regretted that choice on his part. For readers who do not know what the first person singular in the present tense means I recommend tuning into Channel 7Mate where the question will never arise.

I had wanted to read a biography of Dreyfus sometime ago and came up with Jean-Denis Bredin’s ‘The Affair: The Case of Alfred Dreyfus’ (1983) by a French historian so I tried that. Mistake. It started in the middle with the writing test that Dreyfus was tricked into doing. I could never get a foothold on what was going on so I stopped.

‘Murder at Wrigley Field’ (1997) by Troy Soos

GoodReads meta-data is 304 pages, rated 3.79 by 309 litizens.

Genre: krimi

Verdict: George Will would approve.

It is July 1917 and since April the United States has thrown itself into the War to End all Wars. Ten thousand men — doughboys — a day were entering the Western Front. By November 1918 more than four million American men were under arms. Behind them was an unprecedented mobilisation in industry, agriculture, railroads, and shipping. Women joined the work force and blacks moved north to work in war industries. The great Muscle Shoals development began (and it later morphed into the Tennessee Valley Authority). And there was more.

Part of the more was a patriotic anti-Germanism that made it dangerous to be called Schmidt, Eisenhower, Kresbach, Diffenbaker, or anything else that some fool might think was German. Lutheran churches were burned by self-appointed patriots and police had blind eyes. Cities like Baltimore that had more Germans than anything else were patrolled by the army. Even H. L. Mecken had to adopt a low(er) profile. Newspapers were censored. Labour leaders who criticised exploitative armaments manufacturers were imprisoned without trial. Hysteria was in the air along with kerosene. Kayser rolls were off the menu.

Our hero, Chicago Cubs second baseman, Mickey Rawlings lives on double plays, drag bunts, run and hits, choke-ups, tag-ups, inside slides, pick-offs, stolen bases, balks, sac flies, inside the park homers, and barely notices any of this until…….! Then his infield teammate and double play partner, shortstop, Ed Kaiser is murdered. For a time it seems he was killed because of that name, and that seemed plausible in the time and place, but no, there was more to it.

The more emerges as Mickey, reluctantly, becomes involved in the labyrinth of wartime Chicago between home games and road trips. It starts when he delivers condolences to Kaiser’s family and begins to realise how pervasive and pernicious the anti-German feeling is. One thing leads to another and he is warned off, which, per the conventions of the genre, stimulates his competitive desire to find out more.

Profiteers, opportunists, corrupt officials, naive churchmen, jaded journalists, vigilantes, plank thick coppers, all put in an appearance. Though Charles Wrigley’s name is much mentioned, he never appears on the page.

Physics teacher Soos.

Physics teacher Soos.

This entry is the third in a series of kimis set in the world of baseball. There are a couple of these series and I have been curious but reluctant to try them I did sample another one a long time ago that started in Fenway Park and lapsed almost immediately in cliché so that I did not get past chapter two. This one has more life in it, and just enough baseball to offer background. Mickey mixes with many historic figures of the era like Shoeless Joe Jackson, who forgot his spikes once and never lived it down, Burleigh Grimes, Fred Merkle, and their ilk.

‘Selling Hitler: The Extraordinary Story of the Con Job of the Century–The Faking of the Hitler “Diaries” (1987) by Robert Harris.

GoodReads meta-data is 402 pages, rated 3.9 by 827 raters.

Genre: Non-fiction

Verdict: Could not put it down.

The book reads like one of Harris’s historical novels with a cast of characters and skulduggery galore, but it is too incredible to be fiction. Only reality could combine such colossal stupidity, egotistical incompetence, and venomous hypocrisy. In short, it seems like a typical episode of Fox News.

The basics, for those born yesterday, are these. In 1983 there came to light the personal diaries kept for thirty years by one Adolf Hitler. Look him up. It was a sensation and a flock of carrion eaters landed on it to exploit the find.

It all started with an inveterate liar and forger who had eked out a living selling Nazi relics on the black market, since trade in such things was illegal in West Germany. When he could not get the real thing he learned to make replicas. His clients did not seem to notice, or mind if they did notice, so he kept at it. Since trading and possessing such items was illegal the clients did not seek expert opinion or dare to compare notes. Forger also discovered that the objects that commanded the highest prices were those connected personally to Hitler.

He followed the marks, and forged Hitler signatures, early letters, and paintings, a lot of paintings, hundreds. When asked he always said he got the goods from a contact in East Germany, whose name he had to protect because there the penalty for trading in Nazi relics in the DDR was capital.

One day a lowly reporter from the Stern magazine came along. He was a Nazi obsessive, and he bought a few items. Note, though Stern was at the time aligned with the Socialist Party, this reporter was a dreamy fantasist way down the pecking order.

He kept buying from Forger, no questions asked. Then Forger, on the look out for new ways to add value to his small business, broached the prospect of diaries. This was perfect for Fantasist. He tried to interest the editors of Stern in buying the diaries but they rejected them as preposterous and irrelevant. There were many previous examples of forged material from that era, and to their minds this was another pathetic example of that. They knew Fantastist for what he was and left it at that.

Fantastist did not give up easily. In time he by-passed the editors and made contact with the management of Stern. Stern was owned by a holding company which in turn was a subsidiary of the leviathan Bertelsmann corporation. Fantastist convinced Herr Decisivie, the chairman of the board, that this was the scoop of the century. To make it a scoop everything had to be kept secret. So Decisive consulted no one and gave Fantastist a blank cheque to get the diaries: No questions asked.

Fantastist went back to Forger and created a demand for diaries. Forger set to work at his usual standard. He bought ruled A4 school books and used the public records of Hitler’s day-to-day activities to add jottings in Gothic script as diary entries. Over two years he produced 50,000 words spread over fifty A4 booklets. Fantastist spent the blank cheque on them, though he skimmed off as much as 75% for himself of millions. (When Forger later learned of this surtax he readily spilled beans on Fantastist.)

At Stern secrecy remained the watchword. To get some verification very limited graphology tests were done but they were so constrained as to prove nothing, or everything to those who wanted to believe. The Fantastist believed. Herr Decisive was sure of this own genius.

Negotiations with international buyers like News Limited in the UK and Newsweek in the USA brought more people into the secret and doubts were expressed, but dismissed by Fantastist and Decisive as petty jealousies. Decisive had no interest in disproof.

Then Decisive ordered the Stern editors, who had to this point known nothing about this matter, to prepare a special issue. They objected, asking for checks to be made (which would perforce reveal the secret), but were overruled. The international buyers wanted verification but were stalled. They, too, were blinded by the scoop and did not press the matter. At each stage everyone seems to have assumed someone else had verified the diaries. Or so they said in hindsight.

Even as the presses rolled out 75,000 copies of a special, large issue of Stern, a press conference announced the find to the world. It was a fiasco. Faced with a roomful of skeptical journalists some of whom brought along historians from all over the world, the house of cards collapsed. Hugh Trevor-Roper who had authenticated the diaries made a fool of himself, and spent years afterward trying to rewrite this history at least to his own satisfaction. The utterly cynical David Irving played both sides against his bank overdraft and won the lottery that night.

News Limited and Newsweek sold unprecedented numbers of their publications and counted that a commercial success, even while switching to reporting on the hoax that they had generated.

In West Germany there was a police investigation that laid it all bare, sending the little fry: Forger and Fantastist to the slammer – they were held for a time in the same prison specially built for members of the murdering Red Army Faction.

Stern, the Sunday Times, and Newsweek had to show that they took it seriously and scapegoats had to be sacrificed to maintain public confidence in the integrity of the mastheads. [Pause to smell the hypocrisy.]

In each case management, circling the wagons, agreed the scapegoats had to come from down the food chain. Where better than the editors who at each publication had resisted the story until ordered by management to run it. Yet they were the ones fired. ‘They had not resisted enough,’ declared management!

Herr Decisive went on to become the CEO of Dornier Aircraft Corporation. Never ride in a Dornier product is one conclusion to reach from this story. Rupert Murdoch who gave the order to the editor of Sunday Times of London to publish it, over the editor’s objections, was only too happy to fire the editor and blame him for everything while basking in his own genius for the brief circulation increase. The longterm damage to the integrity of journalism bothered no one.

Not even Scott Adams in Dilbert could have concocted a better example of McKinsey management. Credit flows up the corporate chain, and blame flows down.

Harris’s telling is absolutely deadpan. The story is so unbelievable it does not need embellishment.

‘The Fly and the Fly-Bottle’ (1961) by Ved Mehta

Good Reads meta-data is 269 pages rated 3.9 by 16 litizens.

Genre: Non-fiction.

Verdict: A golden oldie.

A charming memoir of meetings with the lions of the British academic establishment at a time when the BBC gave them air time, parliamentarians asked them for audiences, and newspapers welcomed their words. The charm is in Mehta and not his interlocutors.

The subtitle is ‘Encounters with British Intellectuals,’ however all but two of his respondents were ensconced in academia. Few seemed troubled by teaching duties.

The book divides, more or less, into two parts. The first is a series of interviews with British philosophers like A. J. Ayer, Peter Strawson, and their ilk. The second is a parallel series of interviews with British historians, like Arnold Toynbee, A. J. P. Taylor, and the egregious Hugh Trevor-Roper (who went from strength to strength on ever so little), though he is rivalled by E.H. Carr for hubris.

It was indeed a small world since three-quarters of the beasts were in the Oxford zoo, with the remainder, bar a couple, in its Cambridge annex. Small, yes, and all the more venomous for it. The back-biting, the undermining swim beneath surface of the scathing public reviews of each others’ works and days. The pages of ‘Encounter,’ the ‘Listener,’ and the ‘Times’ positively bristled with their poisoned barbs.

It was all so monumentally unimportant that today it is all but forgotten, and a good thing, too. Yet the Platonic dialogues that they despised are still studied.

I loved the story of Hughie writing a long and venomous review of one of Taylor’s books and publishing it with much fanfare in ‘Encounter,’ and then sitting back in the expectation of a rejoinder from Taylor that he could reply to in another vituperative essay in ‘Encounter.’ Taylor did not bother to reply. What a deflation that much have been, like not making Richard Nixon’s Enemies List, despite all efforts!

Among the philosophers the major issue of interest to the laity is the conundrum of free will versus determinism, or in social sciencese: structure versus agency. Among the historians the parallel divide is between meaningful and accidental events.

Amid the nonsense and petty bickering made out to be something much more, there are many telling shafts. I liked historian Herbert Butterfield’s conviction that in teaching history (and political science) one is teaching future officials, diplomats, traders, tariff managers, entrepreneurs, bureaucrats, and so one must equip them to respond to the challenges they will face outside the classroom. Predictably when he uttered this view of academic responsibility in a public lecture he called down the wraith of the gowned gods upon his head who went on about their art for their art’s sake. As if. Few were troubled by teaching duties since they had very few.

Mehta’s ever so oblique and sly digs at his prestigious prey are desiccated. While much of their posturing is, well, posturing, it is well to remember that R. M. Hare’s arid ‘The Language of Morals’ (1951) was drafted while he was in a Japanese Prisoner of War camp in Malaya. However, few of his contemporaries can lay claim to such courageous conviction.

The title is one of the bon mots Ludwig Wittgenstein tossed off, namely, that the task of philosophy was to lead the fly (us) out of the fly bottle (?). Every remark by this sage is totemic to acolytes, so there are many disputed interpretations of this aside, which Ludi no doubt forgot as soon as he said it.

Here is a sampler of the dross and the ore.

Richard Hare dismissed Continental philosophy holus-bolus opining that philosophy can only be taught by the tutorial method (51). Since that method was only used at Oxford and Cambridge it followed only graduates of those universities can be philosophers. He seemed to accept that conclusion when Mehta put it back to him. Since it has only been used there for a short time, there were no philosophers before that. Got it? Ergo Plato, Hegel, Sartre, Schlick, Rawls, and so on are not philosophers.

Wittgenstein thought of himself as a living philosophical problem (82). Amen. Wittgenstein thought only of himself full stop.

J. L. Austin’s linguistic philosophy spread throughout the dominions and America, but not in England because Austin admitted too students from those places (85) [not on its merits], said one don in a huff. It is certainly true that it dominated the curriculum in my undergraduate and graduate education.

Mehta asked E. H. Carr to name historians he admired. ‘None’ was his reply (133). Well, one might suppose there was one, ‘E. H. Carr’ by name.

Taylor wrote, with prescience, of a world where emotions have replaced reason and hysteria has become meritorious (177). He foretold Fox News and President Tiny.

Another bon mot from Taylor: Perfection is always sterile (184). That might be the motto of utopia.

This traipsing through the groves comes to an abrupt stop. But then how could it end. Mehta adds a page and half at the end, drawing no conclusions. These essays were commissioned by the New Yorker and do not quite make a book. What Mehta does not tell the reader is that he became blind in India at four years old. There are a dozen or so of his titles on Amazon.

I read this on paper in the Forgotten Books reprint as picture above. That edition is not recommended because of missing text and omitted pages. I think I may have read some of it in graduate school as relief from analytic and linguistic philosophy.

By coincidence I started to read Robert Harris’s ‘Selling Hitler: The Story of the Hitler Diaries’ where Hugh Trevor-Roper again figures. Egregious to the last. The excuses are many and the facts are immutable.

‘Memento Mori’ (2018) by Ruth Downie

Good Reads meta-data is 432 pages, rated 4.2 by 430 litizens.

Verdict: All hail.

Gaius Petreuis Ruso, Roman legionnaire retired, and his wife Tilla, tribal Britain, are at it again. No, not that. They uproot themselves from the farm in the North of Britain, where Ruso is trying to fit in with the Britains, though he draws the line at tree hugging and singing to carrots, when his old army buddy sends for help. Ruso is only too glad to have an excuse to leave the farm.

Tilla, as usual surprises him, by declaring that she will go along, too, with their infant daughter, nursemaid, hapless slave Eisco, and the exhausted messenger Albanus. This troupe sets off down river, over hill, pass dale, and through mud, through more mud — this is after all England — to arrive at Bath, well it must be but it is not named in the book. Instead of the heroic mercy dash Ruso had imagined, it is a slow plod.

Someone has murdered Serena, buddy Valens’s estranged wife, and he is about to be tried for the crime. He says he is innocent, but Valens has had so little experience in the telling the truth that Ruso is not quite sure whether to believe him. Serena’s father demands justice, and he has lots of large friends who also once served in the legions to back up his call. By the time Ruso and company arrive, Valens is pretty well convicted.

But Ruso never knows when to quit and he asks questions to find that the local priests at the baths squirm this way and that. A trial they do not want. Too public. Too open. But why are they so worried? What are they hiding? How can they hide anything when bathing?

As usual those who know do not say, and those who do not know will not shut up. Sounds like a committee of PhDs at it.

Ruso stumbles around irritating everyone, and exhausting himself. Tilla adds her efforts with little success. There is a large cast of red herrings for each of them to consider. During the consideration we learn a lot about life in Roman Britain, and how holy baths work, including some water engineering. Too bad the British lost the knowledge of bathing when the Romans left.

This is the eighth title in the series and it maintains the standard of excellence. Ruso is so ordinary and Tilla tries so hard. Together they are charming and refreshing compared to the leads in many historical krimis.

‘Astrophysics for People in a Hurry’ (2017) by Neil Tyson.

Good Reads meta-data is 224 pages, rated 4.1 by 58201 litizens.

Verdict: all trip, no arrival. Life’s like that.

An edifying zip around the universe and back. It consists of a series of essays originally published in popular magazines tied together. It works well. The exposition is direct and simple with everyday imagery. I particularly liked the picture of two meltingly hot marshmallows colliding at near light speed. SPLAT, and there we have another star system.

Having no background in the subject, and I would not count the physics I did in college and neither would my teachers, Messers Throckmorton and Bonar, but then I may remember them better than they remember me.* I could not assimilate much of it with no framework or vocabulary in mind.

The single most important thing I can retain from the book is the continuity of matter in the universe. Start dust takes many forms but there is nothing new under any sun.

Tyson finds this continuity and the scale of the universe(s) exhilarating while other might find it intimidating or belittling. He communicates the wonder of it all very well, as do the pictures from the Hubble telescope as above.

The chapters are short, the technical jargon is absent, the explanations are concrete. For a few minutes the reader understands quarks (without Richard Benjamin), pulsars, Big Bangs, black holes, quantum mechanics, string theory, and the carbon in a hamburger. Beat that. But easy come, easy go.

The man can turn a phrase, as in:

‘The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it.’ A truth that anti-vaxxers, flat earthers, climate change deniers, and others will rediscover in time.

There are more than 7000 reviews on Good Reads. Have a look there. Does Tyson keep a scrapbook of such reviews? Do it, Neil!

I was not in a hurry but a short book was the order of the day.

When a conclave of science deniers gets together, Tyson can sometimes be found across the street in another hotel at a podium daring them to bring out their dead arguments. That’s how I came across him the first time, in just such a situation in Baltimore. Some mob of anti-science flat earthers were in one hotel and he pitched up across the street in another to spruik science at them.

Yes, I know he calls himself Neil de Grasse Tyson, but I generally only allow two names to a customer.

* [Censored.]

‘The Invasion from Mars, a Study in the Psychology of Panic’ (1940) by Hadley Cantril.

Like millions of others, Hadley Cantril tuned into CBS radio and listened to the Mercury Theatre of the Air’s ‘War of the Worlds’ on Halloween 1938. The next morning he was surprised to read of the panic that the broadcast had precipitated.

He went to work to analyse this natural experiment. There must be quite a backstory about how he pulled it together so quickly but he did. He started the Princeton Radio Research Project with this initial study.

Because of the reaction on the night, others were also mobilised, and Cantril identified them and cooperated. Because of the public reaction the CBS had committed Roper and Gallup to do surveys. In addition, at least one government agency also did a study. To this mix, Cantril added about 150 interviews with listeners, and a national mail survey of about 1000. He also mailed a questionnaire to the managers of radio station to ask about local reaction. From this combination of data, the book offers some quantitative analysis leavened with case studies.

Cantril’s hope was to explain why the panic occurred. (Many a PhD since has disputed the definition of panic.)

That is, why did some people react in panic to the broadcast, while others did not. What distinguished the former from the latter. He tried demographic explanations, i.e., gender, age, education, social status. He tried geographic explanations. Were those closest to the fictitious New Jersey site more likely to flee their homes? He also looked for psychological factors in the readiness to believe.

The analysis is detailed but the exposition is clear. He found several types who were ready to believe the worst. It was this ‘readiness to believe’ that interested him as a psychologist.

For this reader the social and political contexts have much purchase. After the Spanish Flu epidemic, after the Great Depression, after the Dust Bowl, after the Munich crisis of the previous month, the times were apocalyptic. Bulletins on the radio, newsreels at movies, newspapers, all speculated on a new and terrible war with ever more incredible weapons. They were full of Nazi air armadas, the Italian use of poison gas in Ethiopia, and Japanese atrocities in China. What next?

With all this background someone who tuned into this broadcast and heard of strange weapons and poison gas in New Jersey might fill in the rest.

And all of those who were disturbed by the broadcast were invariably those who missed the introduction and also missed the station break in the middle. They either tuned in late or were not listening to the introduction. By the station break they were already alarmed and again missed it or misunderstood its comforting normality. These listeners received more than was transmitted.

For Cantril the most interesting group were those who tuned in late and heard of the catastrophe and did not panic, but rather did reality checks and concluded there was nothing to fear. They checked by reading the newspaper radio listings, by looking out the window, by going next door to speak to a neighbour, by telephoning the fire service, and so on. Of course, some who spoke to others in person or on the telephone found them in a panic and that contagion had an effect.

But then again, was an invasion of New Jersey anymore far fetched than a Japanese attack on Hawaii, which already in the planning in Tokyo to be followed by balloons released at sea to drift over the northwestern states and explode. Might not the meteor have been a disguised German missile? What became the V-rockets were already a gleam in the eye of some.

Older, more educated, and higher socio-economic status individuals were associated with reality checking but not decisively so. Some older, educated, and wealthy people were millenarians who believed it was god’s judgment on the evil ways of New Jersey. Well I did have a disastrous stay in a hotel — a Hilton at that — in New Jersey once, proving the unexpected happens there.

By the way, Cantril said reality checking was widespread among people who had ‘survived advanced schooling’ (location 1753 on the Kindle edition). Loved the phrasing.

Aside, a few listeners were Sy Fyians and they had no trouble either in recognising the genre or even the specific title. Reading does broaden the mind.

Later Cantril worked for the Nelson Rockefeller’s Office of Inter-America Affairs to gauge public opinion in Latin America during the early years of World War II and to combat Nazi propaganda there. He also conducted a small, clandestine project interviewing Vichy officials in Morocco in 1942. The conclusions of that latter study influenced Allied tactics in Operation Torch.

‘Stowaway to Mars’ (1936) by John Wyndham.

It has also been published as ‘Planet Plane’ and ‘The Space Machine’ under the name John Beynon.

Genre: Sy Fy

GoodReads meta-data is 189 pages rated 3.23 by 525 litizens.

Verdict: What a relief, it has punctuation.

In far distant 1981 there have been Moon orbits but no landings. Why bother, there is nothing there but moon rocks. George Soros has put up millions as a prize for the first flight to and from Mars. Some have tried and failed. Pundits are sure spaceflight is impossible, and publish their opinions as facts on Faux News where Soros is likened to satan since both words start with ’S.’ It was ever thus.

Dale Curtance of the Boeing family builds a rocket in his backyard to win the prize. He is motivated by glory since he already has enough money to build as many rockets as he would like.

Dale is every director’s leading man, fearless, chiseled chin, handsome, genial, sexist, and quick with a shooting iron. He assembles a crew. There is an ageing doctor, an annoying journalist, a navigator who has never been out in space before, and an engineer who is permanently angry, and a stowaway they soon learn. What a carefully picked crew! The doctor will study the flora and fauna. The journalist will keep a factual log. (Fiction to be sure.) The navigator does nothing. The engineer sulks. Dale is fully occupied with chin maintenance. Then the Gloria Mundi blasts off for three-month trip to Mars where they will land and from which they hope to return.

The stowaway is Joan who has come to help. Help? How? By translating Martian. Huh? It seems is a six-legged machine showed up at her father’s farm and she learned Martian from it. Well, so she asserts since no else but Joan and Dad saw the contraption. Those two were sure it was not of this world. That it was intelligent. That….. It did not communicate and yet it did. So goes the circle. Then it vaporised itself. (If only Faux News would do that.) They were convinced it is/was an ambassador from Mars. Having studied the markings on the machine, Joan now feels qualified to translate from Martian. She qualifies for President Tiny’s cabinet with that grasp of facts.

The 1930s sexism is piled on without remorse. Joan is belittled, assaulted, patronised, insulted, and still expected to clean the coffee cups. In fact, this oppression is so detailed, a reader might begin to suspect Wyndham of irony. Or is that too long a reach? Hmmm. See below.

Mid-flight there is a seminar on the relationship between man and machine, and that is man, not woman. It is superficial, vague, and unfocussed enough to be one of those panel discussions on the ABC. They never once refer to the spaceship in which they ride as a machine. Indeed, there is no reason for them to blast off if this is all they have to talk about. Though it becomes relevant, sorta when they get to Mars.

Mars is almost entirely populated by AI machines because the human-like Martians are dying off. There is a declining birth rate, no doubt due to Hillary Clinton, and ever lower resistance to disease, thanks to the anti-vaxxers among them. The remaining Martians see the continuation of the machines as the natural order of evolution and accept it. One tries to explain this attitude to an Earthling, who goes all Luddite and chews an Opal card. This is the most interesting part of the book, but Wyndham had not yet hit his stride and it is talky, talky, and talky. In it, however, Joan is proven right about much for which earlier she was ridiculed by the blokes. That is why I wondered if there was irony in the way the misogyny was laid on. (Albeit there are loose ends, i.e., I never did figure out who sent the machine to Joan’s farm.)

John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris

was the son of a barrister. After trying a number of careers, including farming, lawyering, and advertising, he started writing short stories in 1925. This book was fifteen years before ‘Day of the Triffads’ (1951) and nearly twenty years before ‘The Midwich Cuckoos’ (1957), which became the film ‘The Village of the Damned’ (1960). In these he certainly hit his stride. Each is unique and unforgettable.