A journalistic account of the Amber Room, once of the Catherine Palace near St Petersburg in Russia. It is indeed journalistic, disjointed, breathless, unfocussed, self-centred, inaccurate, and clumsy. One reader’s opinion.

The Amber Room was an Eighth Wonder of the World in its day. Wondrous, indeed it is.

First, what is amber? It is the resin dripped from the trees in the primordial forests that flourished where the Baltic Sea is now. In time it is fossilised into a soft stone, let us say for the sake of illustration. That was millions of years ago. The smell in a pine forest is carried by the resin excreted by the trees. In sustained hot weather it drips from the trees. The drips pile on top of each other in clumps like small stalagmites. With rain and then climate change these clumps on the forest floor were washed into the rivers and thence into the emerging and enlarging Baltic Sea where tidal action drives it into pockets along the shore. Most clumps are the size of a golf ball or smaller, which are too heavy to float on top and too light to sink to the bottom and stay there.

Red amber.

Red amber.

Amber has been valued as jewellery since human habitation in the region. In time artisans learned how to work it, by carving and polishing and then later using heat to shape it, then to dye it with vegetable extracts, wine, or honey. Most prized became clear pieces in which an insect was trapped by the sticking, dripping resin. These were talismen for pre-historic Nordic peoples. We saw some spectacular examples of such jewels in our Baltic sojourn in 2016.

One of the prizes of the Baltic Coast of Prussia was amber. There is a superb krimi which is set among the women who harvested amber for the Hanseatic market in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, Michael Gregorio, ‘A Visible Darkness: A Mystery’ (2011), one in a series based on a judicial officer, Hanno Stiffeniis. Very atmospheric and detailed.

In the Prussian court of the Seventeenth Century there occurred a rivalry among architects, artists, decorators, and artisans for the favour of a new queen, Charlotte, later of Charlottenburg Palace. One competitor who was being displaced by younger rivals, knowing the King’s reluctance to part with a pfenning devised a project based on using what was already in storehouses, tons of amber in those clumps. There followed a technological leap from small items of jewellery to panels twelve feet high and three or four feet wide.

At the time an ounce of amber was more than ten times the value of an ounce of pure gold. It was more rare and precious than gold by a factor of ten. It had been stockpiled because the cost of the jewels limited the market. No other Baltic country had such riches of amber on its shores, thanks to the peculiarities of tidal action, location of ancient forest, etc. The idea of using what was sitting in the basement appealed to the king, and the project started to create an amber room, i.e., a room panelled in amber. Extraordinary as it was it did not find favour and the panels, once made, went back to the storeroom.

In 1701 Prussia and Russia were allies against the Swedish juggernaut, and to seal the deal the Prussian king wanted to entrench himself with Peter the Great, Tsar of all the Russians. Peter had a fondness for amber, and ‘Voilà!’ There was the answer, a gift like no other to someone who would appreciate it. The amber panels were packed up and dispatched to St Petersburg. Peter was overwhelmed but there was a war on and the panels stayed in boxes.

The Tsarinas who succeeded Great Peter did have the panels mounted to create a room but moved it several times. It is fragile when extended to the size of panels and there must have been breakage but no details were recorded. Then the German Tsarina, who had grown up with amber jewellery, came to the throne and she made what became known as the Amber Room in the eponymous Catherine (the Great) Palace, a summer residence outside St Petersburg. Walls were lined with gold and silver leaf foil and the amber placed over it interspersed with mirrors. In flickering candle light, with bejewelled courtiers moving about the very walls themselves would seem also to teem with life.

There it stayed, surviving the revolutions and upheavals until 1942 when the advance of German armies targeted Leningrad, as the city had become. The order went out to all Soviet cultural institutions west of the Ural Mountains to pack up everything and ship it east. So much easier said than done. None of the curators had experience in moving whole collections and everything necessary for the task was in short supply, from timber for packing cases, to men to load them, to railway cars to transport them.

In the Catherine Palace the Amber Room was the obvious priority, the problem was how to dismantle it without destroying it, and then how to ship it over roads and rails under aerial attack. Heating in the Palace over the years had made the amber brittle, even more fragile as early efforts indicated. If cracked, some pieces simply disintegrated into dust. In the end the responsible curators could not square this circle and to the sound of German artillery decided to hide the Amber Room with its tons of amber by papering over the walls and painting the floor and in another adjacent room they tried to make it look like wall panels had been removed from it. Nice try.

As the Wehrmacht advanced there followed in its train the treasure hunters, special units commissioned by Hermann Göring to loot treasures and send them back to the Reich. The Amber Room was at the top of the list for these units approaching Leningrad.

The Germans occupied the Catherine Palace area quickly and the Amber Room disappeared as the siege of Leningrad began.

From this point onward information is fragmentary, partial, hearsay, distorted, self-serving, false, and incomplete. In the crisis of war and battle records were not always kept in detail and many such records as were made became collateral damage in the German advance and then three years later in the Russian advance. The Red Army was followed by its own treasure hounds to reclaim looted goods and to loot more as reparations. At the top of their list was…. The Amber Room.

The records that do exist show that the German treasure hunters found the room quickly and dismantled it in thirty-six hours! That is hard to credit. There is no record of how much damage was done in that haste. The German records show that the trove and much else from the east was shipped to Königsberg, the historic capital of Prussia where it was placed in the Castle Museum. This city is so far east it is now in Russia, Kaliningrad, once home to Soviet boomers.

In January 1945 the Russians were coming and the RAF was bombing Königsberg to block the harbour, destroy the railroad yards, cut roads, and then to destroy the town itself. Half the Castle was destroyed either by RAF bombs or Red Army artillery. A few weeks later, after the Soviets had taken over the rest of it was burned either by accident or design. On one of these occasions the amber of the Amber Room went with it.

Königsberg Castle in 1945.

Königsberg Castle in 1945.

Everything after the initial receipt at Königsberg is vexed, contradictory, inconsistent, undocumented, rife with conspiracy theories, and lost. Despite the many years the authors spent on the trail, they found nothing because there was nothing to find. This fact is disguised by the pitiless details that are heaped up in the book as though altitude yielded enlightenment. The authors, seemingly fluent in both Russian and German went here, there, and everywhere in Russia and Germany to track down survivors and records. The ensuing discussions were fruitless and the records scant, Instead we have endless detail of the number of stairs climbed, the knocks on the door, the shuffling feet heard inside, the second knock, the forms filled out in archives, the colour and feel of empty file folders, the cigarettes smoked by interviewees, the aroma of the tea offered, the mercenary attitude of Russian museum staff, the apologetic demeanour of German curators, and on and on. A traveller across a desert may describe in detail a mirage, but it remains a mirage, and these two travellers have described in detail the illusions they chased…to no avail. It is all trip with no arrival.

My impatience with the journalistic style together with the dawning realisation that there was no story to tell, led me to reading only every other page and then later every other chapter. I did not miss anything. This was a technique I learned in graduate school to cope with the impossible reading assignments, though with that reading I did miss a lot. Though even with this stream-lined approach it was still heavy going.

Having heard many stories of our Russian travels, a friend lent me this book. He said it was overlong. What a subtle understatement. As to substance it is indeed overlong, as to content it is short. Fully three-quarters of it is puff. By the way the giant equestrian statue near the Arsenal in St Petersburg mentioned early in the book is of Peter the Great, not Catherine the Great. Nor is Saxony south-east of Königsberg on map. Perhaps a new prescription for contact lens is in order.

Catherine Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy

Catherine Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy

Yes the book has a lot to say about the rivalries among curators, the terrible political infighting, the disastrous wars, the personalities involved, but such subjects are treated in many far better books by historians, biographers, and novelists than this effort. It is described as a best seller, but what is not so described today.

For an orderly and succinct exposition of the Amber Room turn to Wikipedia. A replica was completed in the 1990s and we saw it on our tour of the Catherine Palace. It is indeed a wonder though lacking in the mystique of the original.

Category: Book Review

‘The Book Smugglers of Timbuktu’ (2017) by Charlie English.

The word ‘Timbuktu’ entered vernacular English in 1863 as the most distant place imaginable, according to the OED. It has had many spellings over the years but the one used here is the standard in Wikipedia. Most who have heard the word take it to be mythical, but in fact it can be found on a map, in the sub-Sahara West African nation of Mali.

Timbuktu gained some recognition among the Nerd Empire in the late 1990s for the collection of medieval and even ancient manuscripts gathered there, and more when these treasures were threatened by fundamentalists whom god had told to destroy all. Not all the nut cases are in D.C.

A building in Timbuktu.

A building in Timbuktu.

The airport at Timbuktu

The airport at Timbuktu

This book combines the Nineteenth Century story of Europeans exploring the interior of Africa to find this very place with the Twenty-First Century story of saving its aforementioned records from the flames.

The quest for this African El Dorado began in the mid-Victorian period when intrepid chaps in Britain were looking for new adventures. Africa, the dark continent, beckoned. It was called the ‘dark continent’ and ‘darkest Africa’ not because of the colour of the skin of the natives but because it was unknown, in the dark. There was plenty of racism but this term was not an instance of it at the outset. Later, yes, certainly. say as it was used in the 1950s in Disney cartoons.

In part the book traces the efforts of the African Association in London to explore, map, and study Africa, partly directed by the affable Joseph Banks, who as a young man had accompanied James Cook on his voyage to Australia, and after whom Bankstown is named, along with flora. The method this private organization took was to recruit a series of intrepid men and send them off one-at-a-time. Off they went and mostly disappeared into darkest Africa, never to be seen or heard again. Disease, dehydration, animals, sand, stupidity, accidents, villains got them one after another. Inevitably, a Société d’Afrique in Paris got into the game so that the rivalry between England and France was played out on the way to Timbuktu. Then came the Germans looking for that fabled place in the sun.

On the other hand is the story of the threat posed by fundamentalists, which is told in the choppy and breathless manner that distinguishes contemporary journalism. It is a sandstorm of names and places that mean nothing to this reader, and at no point is there an orderly exposition of what the manuscripts, papers, and documents are, how they came to be in Timbuktu, and who had formal responsibility for them. Nor is there anything more than the repeated assertion that they are valuable to justify the importance assigned to them. In the telling, it sometimes seems this town on the sand just by chance was home to a number of private collectors who had somehow gathered the written material and at other times there are references to libraries, catalogues, steel boxes, and UNESCO grants. Later there are few references that indicate that Timbuktu became a centre for learning in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, but by then I was so lost it did not help.

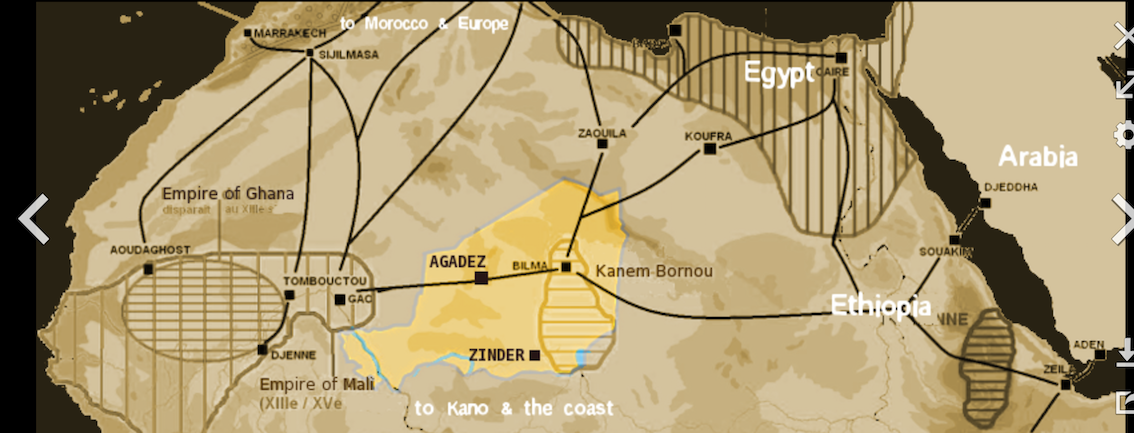

This map below from Wikipedia shows when and why Timbuktu (Tomboctou) was an important crossroads that benefitted from proximity to the mighty Niger River, from which proximity it also suffered when the river flooded. The lines are trade routes used at various times.

That combination of two stories is both an asset and a liability. It is an asset because it makes clear the importance of Timbuktu and its holdings and a liability because the author has a lot more to say about the latter story than the former and so it is unbalanced.

Trashed books in Timbuktu

Trashed books in Timbuktu

While the telling is repetitive and confusing at times, the subject is so important that I tried to persevere through all the confusion that the author reproduces.

There is a shower of proper names, descriptions of men with guns, the arrival of trucks, comings and goings as though this is a thriller. Well it is a mystery to this reader. One that remains unresolved.

Charlie English

Charlie English

I supposed the author was a journalist from the disjointed style, the disregard for readers, and the indifference to exposition, and then I checked. Sure enough. He and this book get a lot of space on the ‘Guardian’ web site. Make up your own mind. I have. With perseverance I made it about halfway through before deciding I would learn more reading Wikipedia. No doubt Good Reads is replete with fulsome comments. No doubt the dust jacket of the hardcover proclaims it a best seller. No doubt.

Jan Morris (1926+) née John Morris, ‘Venice’ (1960), Third Edition (1996).

A charming, enthusiastic, and altogether delicious memoir of life in Venice in the 1950s. It has an intimacy born of residence which goes into the details of everyday life, like rubbish removal, and the weekly shopping by dingy. Indeed, it includes many asides on the perils and joys of keeping a small boat for just such mundane purposes, and the surprising array of regulations and taxes that a humble, leaking rowboat attracts, watertight or not.

The Venice of the 1950s is gone, but Morris is confident that as long as there are Venetians there will be a Venice. The gene pool is strong, deep, resourceful, and clever enough to withstand the tides and times, Morris opines in the 1996 introduction to the reprint of the book, originally published in 1960.

The approach is almost ethnographic, as an anthropologist living amongst a tribe in the African savannah, he observes, notes, compares, enumerates, and ponders the meaning of what he sees, but with much more affable affinity than a Cambridge don in khaki kit roughing it for a few months in the jungle on the way to promotion. Morris spoke enough Italian to get to know the regulars he met, and enough to talk his way into some places not usually open to nosey beaks. He combines with those assets a keen eye and a tireless pursuit of detail that would satisfy John Ruskin. To these he adds a bonhomie that is hard to resist. Well, why resist it at all?

A quiet day at San Marco.

A quiet day at San Marco.

Day by day over the months Morris weaves together many asides on the history that brought Venice to the current point; these accounts often take the form of lists. That might sound boring, but it is not. Consider the following example as one of many instances.

Here is Morris’s dictation while standing on the tiny balcony of the flat there was:

‘To the left is the palace where Richard Wagner wrote the second act of ‘Tristan,’ and just beyond is the terrace from which Napoleon Bonaparte once watched a regatta. Near it is the house where Robert Browning died, that Pope Clement lived in it, the Emperor Francis II also stayed in it, and Max Beerbohm wrote about it. Across the way at that point is the home of the Doge Cristolo Moro, sometimes claimed to be the original of Othello, and to the right is a palace once owned by a family so rich that it is still called the Palace of the Money Chests. At the corner is the little red house of the poet D’Annunzio wrote ‘Notturno’ there. At the Convent next door Pope Alexander lived in exile from Rome. King Don Carlos of Spain once owned the next house along. La Donna of ‘La Donna è Mobile’ lived nearby. Away to the right, is a palace where one of Byron’s paramours suicided.’

All of this lies within one learned glance.

That is both a comment on how compact is the core of Venice, and also, and more importantly, a comment on what a magnet it has been for the great and good and the not so great and the not so good over the centuries. Yes, Adolf Hitler met Benito Mussolini there in 1934.

Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini

Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini

Followed shortly by Indiana Jones.

Morris goes on to enumerate and describe the many watercraft to be seen in the lagoon from towering cruise ships to garbage scows, to vaporetti and gondoli, and in many cases goes into the etymology of the terms in part to show the polyglot past of Venice with its Arabic, Islamic, Roman, Teutonic, and Byzantine influences, turning the catalogue into a history lesson, spiced by Morris’s own experiences in dealing with many of the craft as either a passing boatman, or as a passenger.

Venice conjures the gondola and Morris gives it due respect. Totemic though it is of Venice, there is no clear explanation of its origins, purpose, or use. Why does it have three notches in the bow? Why is it propelled by a pole and not an oar? Why is it painted black? While the number in the water has decreased by many factors, it remains in demand … by tourists. Morris offers a charming account of both past uses of the gondola and the occasions when contemporary Venetians make use of this clichéd but inevitable device.

Like others who have written of Venice, Morris sees in it a deeply ingrained commercial imperative to make a living out of trade. Having no natural resources, Venetian has always been a broker bringing products to a buyer at a premium. The commodities that Venice can make a profit trading have diminished and disappeared, that is, all but one. The one commodity that Venice retains a monopoly on is itself, and so it trades on itself and does that to a T for Tourism.

Jan Morris.

Jan Morris.

Upon completing the book, I am not sure what to make of it. To read it is to envy the author’s mastery of the exposition. This writer could make a recitation of a telephone book interesting, and indeed, did so in these pages. In some ways it is a memoir of a world now gone. As Morris found even while living in Venice human intervention changed the face of Venice time after time with causeways, channel dredging, factory building, and more, and also the lagoon itself makes changes, eroding what were once residential islands into little more than hillocks of sand.

But the more Venice changes the more it remains exactly the same! Grasping and enchanting, mercenary and magnanimous, seedy and edifying, grotesque and elegant, universal and unique, quite unlike any place else.

‘Venice: Pure City’ (2009) by Peter Ackroyd

The book is an elegant and languid meditation on the city of Venice, the one in Italy not the one in California. It tells the story of Venice through thematic chapters rather than a sequential history. The chapters run ten to twelve pages, easily digestible in a sitting, and the segues from one to another and within each are smooth as the surface of a pond on a still day. Without a doubt the man can write. The book is replete with watery images, metaphors, comparisons, similes, and tropes. I felt moist reading it at times.

A sample of the chapters includes; Origins, Trade, Refuge, Stones, Chronicles, Secrets,…..

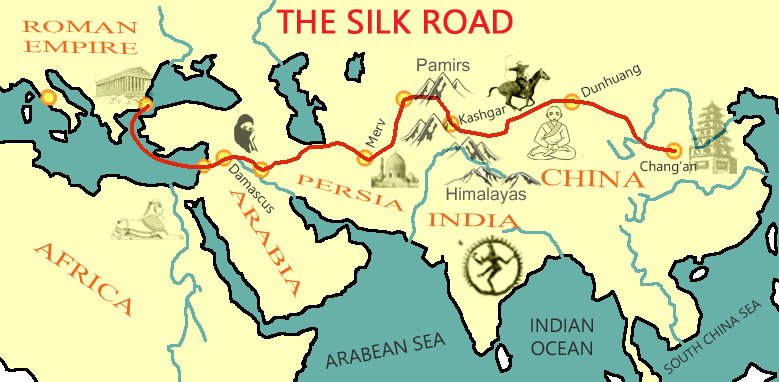

Leaving aside a myriad of details, the heart of Venice was and is trade. It made itself an entrepôt for more than a thousand years. Having no wealthy terra firma, having no mineral riches, having no vast population, it lived by wit, barter and trade. It became the European end of the Silk Road. The merchants Shylock funded sailed into the Black Sea and along the Levant coast to bring back to Venice the luxuries of the East and sold them in trade fairs in Venice. The first Venetian carnivals were commercial expositions.

During its long ascendancy, when violent change was the norm in other polities, precipitated from within by ambitions or ideologies or from without by invasion, Venice remained stable. The city lived with the constant threat alta aqua, which made Venetians pull together, however much they grumbled, like no others at the time. Until Napoleon in 1804 joined it to the Italian kingdom he created for his brother it had stood apart from one and from all. Having no choice Venice reluctantly and slowly became a part of Italy. Earlier when Niccolò Machiavelli rhapsodised of a future Donna Italia he did not include Venice in it, and in this he was not alone seeing it as an enemy of Italy, not a part of it.

In Venice the commercial imperative reduced everything to a contract, and copious records were kept which miraculously survived despite many catastrophes natural and human that often destroy the past. Ackroyd has immersed himself in the dry and dusty ledgers when not walking the campi and picked out some very apposite instances for the reader.

Venetians were traders for whom the sea was the highway. They bought cheap and sold dear and on the margin prospered. Though the merchants were private businesses, their activities were supported, encouraged, promoted, and taxed by the commune as a whole. To specify, the ships were built and owned by the commune and rented to merchants complete with crews. There is a parallel here to George Pullman and his famous railway cars, which are treated in another review on this blog.

Because of the historical and ever-present threat of the water the communal spirt ran deep, and lasted longer even in the age of Enlightenment individualism. In Venice the whole comes before the one. Else everyone drowns. The comparisons to Amsterdam are many.

Like many others he is impressed by the Venetian drive for order and regulation, the more so in the face of repeated Venetian corruption, extortion, embezzlement, and fraud. Shylock was the least of the problem for most merchants of Venice. Ackroyd is absolutely deadpan in the chapter called ‘Merchants of Venice’ in which he does not mention William Shakespeare and his Venetian play. If he did, I blinked. Earlier he does mention Venice’s most famous literary tourist, Gustav von Aschenbach from Thomas Mann’s mediation on life and death … in Venice.

Everything was put down on paper, moreover, everything was kept totally secret. There is the paradox, everything was recorded, included the energetic informing on each other that kept the authorities busy processing, but nothing was said. Ackroyd cites some remarkable examples of the ability of Venetians to keep secrets. They make all those Stasi agents in the Deutsche Demokratische Republic (DDR) look like blabbermouths. There are many, and to this reader, surprising comparisons to be made between the DDR and Venice in matters of secrecy, security, and surveillance and the high cost of such social control.

In the case of Venice the campi — the residential squares — made surveillance unavoidable even for those few who were not interested in spying on their neighbours, and easy for the great many others who were interested. One result is the hidden doors of many houses, so placed to avoid prying eyes. Another result was the mask and cape.

Yes, there is a ‘but’ coming. The book is all trip and no arrival. Though each theme is treated clearly and simply, this reader lost impetus. Without a sequence of events the reader has no characters upon whom to focus or chain of events to follow. Of course, the author’s choice to do that puts all the focus on the city of Venice and Ackroyd’s considerable powers of persuasion, and it kept me reading.

‘Doge’ is a dialect corruption of ‘duke’ and they come and go but none move the story on. Doges were invariably elevated at an advanced age, say seventy-two, and some then continued for another twenty years. There was an unbroken line of one hundred and twenty doges until Napoleon brought the Enlightenment on the bayonets of his army. The regime, in the terms of comparative politics, was authoritarian, oligarchic, patriarchal, and gerontocratic. That is for those who suppose labels are explanations. Napoleon, extracting a huge tribute from Venice, had the Golden Book of the Doges publicly burned. It was the genealogical register of the ducal families, the clan that sired the succession of doges, and its destruction completed the rupture with the past.

Venice was a republic; it did not have hereditary monarchs, though successful and powerful families strove for dynastic succession, and it did not have a feudal past in which a few owned the land and the landlord owned most people. The social strata were thus not the hard sediment they became elsewhere, but they hardened over the millennia. No gondolier ever became doge and no scion of the Golden Book ever poled a gondola.

Its foundation, existence, continuation, wealth, and stability depended on trade over the seas, and that trade required a great many skilled artisans to build, maintain, and repair the ships that were rented to merchants. The importance of these skilled craftsmen gave them more leverage in Venice than in many other comparable places. It is easier for the workmen at a single shipyard, the Arsenal, together to make their displeasure known than for an equal number of peasants scattered over vast estates to do so. See Gdansk in Poland for further confirmation.

The pages of the Golden Book represented about four percent of the population and the mercantile strata added another six percent, leaving the ninety percent out of the political, social, and financial elite. Those of the Golden Book tried hard to marry only within its own small ranks, and the merchants married their own kind when not trying to marry up. The total population in its prosperous times numbered about 100,000, more than it does today,

As with cities like Florence in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, the government of Venice was complicated and convoluted, by design, not by accident. When problems arouse a committee to act on it would be created and it would inevitably perpetuate itself in the first law of administration — goal displacement — revealed in 1957 by Philip Selznick in ‘Leadership in Administration.‘ There grew an encrustation of such committees with vague and overlapping remits, that never seemed to lapse. They often worked in ignorance of each other even when they had overlapping membership the law of secrecy applied. While laws were written, they were never codified and seldom promulgated and enforced only when necessary. It sounds very much like a university Department’s approach to self-government in the days when that was tolerated.

This open texture might seem to offer many opportunities for citizens to play one committee off against another, as is commonplace today in organisations, but not so in Venice, because the existence of most of these committees was secret, so secret that other committees with exactly the same terms would be created anew, and all of their activities were secret, too, including from each other.

Of course, there was no written constitution that spelled out anything. Some of that may remind a reader of working in a large organisation without an organisation chart, and no reporting. Yet everything is recorded. Ahem, see the passing remark above about a university department.

In a way, though prima facie more formal with its archive, it reminded me of the rule by talk in Colin Turnbull’s ‘The Forest People’ (1961) where every instance is treated as unique and talk, talk, talk until the antagonists prefer to give way than talk anymore, like those self-governing co-operatives in the 1970s where everything was done at all-staff meetings that went on, and on, and those who persisted eventually got their way. It was self-management by verbal attrition. Compared to this, McKinsey management looks better.

The Venetian mask a perfect metaphor for the pure city. It is ‘pure’ by the way because it had for most of its history no hinterland with apologies to Padua. It was all city and nothing else. While Florence had a rich agricultural land in its domain, where the Medici family raised beef cattle that still grace the plates of Italian cuisine, Venice had only itself and the lagoon.

In Venice care was taken to be sure that the archivist was either blind or illiterate so he could not read the files, unlike Connie in the John Le Carré Cold War novels. The files might be sequestered but Connie knew what was in them despite the sealing wax. The files might be altered but Connie forgot nothing. Corporate memory resided in one sodden pensioner.

That passing mention of Padua reminded me that Venice has another connection with Machiavelli. Cardinal Reginald Pole who broke with Henry VIII spent an exile in Padua where he became aware of Machiavelli’s ‘The Prince’ and wrote a condemnation of it, though it is doubtful he read it. Since King Henry’s confident Thomas Cromwell had earlier spent time in Italy, Pole supposed that he learned his sins from Machiavelli. Association is poor proof of cause and effect, but this tenuous thread is woven into Hilary Mantel’s Tudor novels.

Today Venice remains a city of trade, and its trade is with tourists who come to it as if the whole city is a continuous exposition. Venice remains an entrepôt and the product it mow sells is itself. The tourist Venice, the Venice a tourist sees is Venice, he concludes.

While Ackroyd’s impressionistic tour refers to the mysteries and crimes of Venice the dedicated krimi reader turns to Donna Leon for detail.

Peter Ackroyd from the dust jacket.

Peter Ackroyd from the dust jacket.

This book is all trip and no arrival. It meanders here and there and Ackroyd is a superb cicerone.

“The Invisible Gorilla: And Other Ways Our Intuition Deceives Us‘ (2010) by Charles Chabris and Daniel Simons

This book is a popular presentation of some serious studies in the psychology of perception and memory. It shows how counter-intuitive reality can be. It also overstates its case and enforces a technical vocabulary where it adds little or nothing to the general reader, who seems to be the target audience.

The video that made the authors famous and which explains the title can be found on You Tube. It is a psychology experiment in which observers are instructed to count the number passes a basketball team makes, and while the observers count, a gorilla walks across the court. Well, a student wearing a full-body gorilla suit, since the research grant did not run to capturing and training a complaint gorilla.

Imposible to miss!

Hmm, missed by about 50% of all subjects through repeated iterations and variations.

We can indeed miss things in front of our very eyes, and do so nearly every day. So I say from personal experience. Because we miss them, we suppose they were not there, but they were.

The explanations are many, and in these pages become increasingly, and needlessly, complex, no doubt to justify the grants that produced the fame and book contract(s). My cynicism is showing.

We see most readily what we are looking for. Indeed we often can only see something if we are looking for it, and in concentrating on that, we miss much else. Whoops! But then concentration is supposed to do that, focus.

In parallel we are less likely to see what we are not looking for, and the even less likely to see it, the more out of place it is. This latter is counter-intuitive. But that gorilla is an example. It is completely out of place and, consequently, invisible (to half the watchers). Another player, a coach, a referee, a cheerleader wandering onto the floor might have been spotted more often for the fit the context.

To reiterate. something extremely odd can be the most easily missed. See, counter-intuitive, because one would think the oddest things would stand out, but they do not always do so. Sometimes, yes, but often times no.

Add to this perception blur-memory and the plots thickens. If it is not perceived in the first place but is just a blur, memory cements over it, and it never happened.

The authors demonstrate these failings, which seem very plausible in my own personal experience, with a combination of laboratory experiments and case records of automobile accidents, flight simulator video evidence (nearly enough to put me off flying), conflicting eye witness testimony, and trial records. The range and variety of this empirical evidence is impressive.

One of the governing points is that our contextual expectations shape perception and also memory. We do not expect to see a gorilla while a basketball team practices passes.

There is also cognitive load, which the authors do not give any attention, but they do note that when the task assigned to observers is made more difficult, gorillas sightings decrease. For example, to ask observers to count separately air versus floor passes makes the gorilla all but invisible to everyone. The more complex the assignment, the more concentration it takes, the less attention remains to detect the unexpected.

There is another example of cognitive overload in these pages. Drivers who follow the GPS oral directions despite the obvious mistake it is making. They ignore flashing lights, barriers across the road, and drive off collapsed bridges, over the culverts of incomplete roads, and on to rail way tracks because the computer voice told them to do so. I would like to think I would not do this, but…. I have found GPS directions mistaken when roadworks blocked the recommended routes and had the wit to stop on those occasions. Who knows what the future will bring?

Of course, magicians and other illusionists have long exploited misdirection, distractions, sleights of hand, and lighting to make audiences see what the magician wants its members to see and not what is in fact happening before their very eyes. The authors have not yet referred to this domain in my incomplete progress through this book. Though the illusionists do not publish in ranked journals and apply for National Science Foundation grants, hide behind polysyllabic jargon, nor make mountains out of molehills as scholars must, so they may get short shrift in these pages.

There are many more ingenious experiments to justify research grants. If magicians are neglected so too is the simple fact of concentration. If I am concentrating on counting passes maybe I should not see the gorilla. Perhaps the observers who see the gorilla made mistakes about the pass count. Nothing is said about the accuracy of the observations, but if I were paying pass-counters that is what I would want them to do, count, not notice gorillas. Many of the examples given involve witnesses who are not concentrating. A student passes people on the street, and one says ‘Hello.’ Five minutes later the student cannot describe this person. Well, so what? If that student had been told the description would be on the final exam, it would have been remembered.

Two passengers in a moving car see an assailant pull a bike rider to the ground. Interviewed by police thirty minutes later and they give different description of the assailant. Again, so what? They were not concentrating on the scene. It was a blur.

Of course, the authors’ point, is in part, that such witnesses each individually think they do have an accurate description even when one, if not both, of them must be wrong. It is this confidence that is the underlying problem, and the authors nail that. It is the this also confidence that presents many problems. Agreed, but I am not sure this book has narrowed that down any.

Though in doing so, it seems like overkill. The messages seems to be that no one is ever right in the first place and subsequent memory further erodes. To give up would seem to be the best response to such a hopeless situation.

I thought of these two when reading about memory in this book.

I thought of these two when reading about memory in this book.

Hmm, well I just watched an American football game and there the players with enormous concentration remembering intricate plays from a manual of fifty or more, in a deafening stadium, driving rain, with hard hitting opponents, carrying injuries, and growing tired toward the end of the season and the end of the game. Memory does work better when one concentrates.

The authors offer some amusing anecdotes to illustrate the fragility of memory but to this reader that is all they are: anecdotes. Men often appropriate each other’s stories as their own in the retelling and when challenged about it, get very defensive. (I have even seen women do this.) What is going on in such cases is not primarily a false memory but a stupid lie followed by a masculine refusal to admit it. No National Science Foundation grant is required to explain this everyday event.

More disturbing are airline pilots in simulators who are so absorbed in reading gauges that they do not notice the tanker-truck on the runway.

A tendency in this book is to name a ….a what? … a syndrome, and then move on to another ingenious experiment. The missed gorilla and the missed tanker truck are treated as instances of the same tendency and yet they differ so much in context and consequence as to be different in kind.

Moreover, to this lay reader (I thought about say layman to see if it would arose a comment about gender but I forgot) that the nominalism is not very informative. By nominalism, I mean naming a pattern of (mis)perception – e.g, inattention to change, and suppose we now understand how it works. We do not; what we have, often in these pages, is a description with a label.

Charles Chabris

Charles Chabris

Daniel Simon

Daniel Simon

While I am airing my nits, I find the book replete with name dropping of colleagues and of universities. Perhaps some editor encouraged that to make it more personal and less austere and scientific for a general reader but it makes it read too much like a letter to mom identifying all of the fraternity brothers and sorority sisters. It is all of a piece with the me-ism of the selfie.

Warning! cynicism overload.

The 100 Greatest novels?

We spent several hours, day and night, discussing Robert McCrum’s list of ‘The 100 best novels written in English’ from the ‘Guardian.’

Google will produce several associated lists but the one I mean is found at

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/aug/17/the-100-best-novels-written-in-english-the-full-list

The list is the product of two years of ‘careful consideration.’ The introduction refers to the list as the ‘greatest’ novels.

The work must be a novel and written in English. When we went through the list we also supposed there was an additional element, every author only has one novel listed. They are listed in chronological order.

Yes, one can quibble over the definition of a novel, or even perhaps written in English (see the impenetrables below); entertaining perhaps, but hardly productive. And then there is that word ‘great’ constrained by the number one hundred. What does make a novel great? On there a few words at the end.

We read the list and discussed what we knew about each writer, or took note of writers that were unknown to us, consulting Professor Wikipedia at times for more information.

The list begins with ‘The Pilgrim’s Progress’ (1678) – a ‘story of a man in search of truth told with clarity and beauty,’ says McCrum. Much as we like Geoffrey Chaucer’s ‘The Canterbury Tales’ (1386), a novel they are not.

Robinson Crusoe, Lemuel Gulliver, Tristram Shandy, Tom Jones, Clarissa, Emma, and Dr Frankenstein get their dues.

The first krimi is Wilkie Collins’s ‘The Moonstone’ (1868). Though Edgar Allan Poe is there with his one spooky novel, along with Arthur Conan Doyle, Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler follow, but not the uncrowned king of noir, Ross Macdonald. Tsk. Tsk.

We loved the description of George Elliot’s ‘Middlemarch’ (1872) as ‘a cathedral of words.’

Benjamin Disraeli is there, before he became British prime minister, but also Jerome K. Jerome. Who?

There were others that struck no bell with me:

George Gissing, ‘New Grub Street’ (1891)

Fredrick Rolfe,’ Hadrian the Seventh’ (1904)

Max Beerbohm, ‘Zuleika Dobson’ (1911)

Sylvia Warner, ‘Lolly Willowes’ (1926)

Henry Green, ‘Party Going’ (1939)

Elizabeth Bowen, ‘The Heat of the Day’ (1948)

Elizabeth Taylor, ‘Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont’ (1971)

Marilynne Robinson, ‘Housekeeping’ (1981)

Penelope Fitzgerald, ‘The Beginning of Spring’ (1988)

Joseph Conrad’s ‘The Heart of Darkness’ (1899) made the cut. But is it a novel or a long short story? Quibble. Quibble. The trouble with quibbles.

Also on the list is the impenetrable prose of Theodore Dreiser of whom is it is said ‘he was no stylist.’ Indeed. Speaking of the impenetrable, there is Ford Maddox Ford, ‘The Good Soldier’ (1915) and James Joyce, ‘Ulysses’ (1922).

While there were many famous titles, I was not sure all were great novels. There was John Buchan’s ‘The Thirty-Nine Steps’ (1915) which is a rattling good story, but is it a great novel? It may be the cornerstone of the espionage genre that followed, but is that enough to merit inclusion when Agatha Christie is omitted?

It will take a lot more than assertion to convince me that Ernest Hemingway wrote a great novel. The title is ‘The Sun Also Rises’ (1926). Oh hum. I also wondered about John Dos Pasos, ‘Nineteen-Nineteen’ (1932) and ‘At Swim-Two-Birds’ (1939) by Flan O’Connor and — most of all — H. G. Wells with ‘The History of Mr Polly’ (1910). For Wells I might have swallowed one of science fiction titles like ‘The Time Machine,’ ‘The Invisible Man,’ or ‘The War of the Worlds’ but not this trite and self-indulgent disguised autobiography.

While the demigod William Faulkner is there, the novel cited is not his most astounding. ‘As I Lay Dying’ is the one, but his most hypnotic novel is ‘Absalom! Absalom!’ (1936). The novel he thought was his best was ‘The Sound and the Fury’ (1929). By ‘best’ Faulkner meant the most painfully true.

One book authors are here like Harper Lee.

Carson McCullers who is in another, higher league than Harper Lee is not, nor is William Styron.

Two towering English writers are also conspicuous by their absence: Barbara Pym, ‘Excellent Women’ (1952) and Antony Powell, ‘A Dance to the Music of Time’ (1951-1975). Also absent is John Galsworthy, ‘The Forsyth Saga.’

The list ends with a number of contemporary writers, most of whom leave me cold, e,g., Martin Amis, John McGarhan, Don DeLillo, and Peter Carey. More oh hum from me.

In addition to the expatriate Peter Carey, Australia is represented on the list by the egregious Patrick White. Absent is the luminous David Malouf; when will the Nobel Committee wise up?

David Malouf

David Malouf

There is a Canadian writer, or two, but not the profound Gabrielle Roy, a bank clerk by day and a communicate with eternity by night. To this day she is listed on the Amazon Canada web site as Roy Gabrielle, despite many corrections offered by we readers!

Whoops, Roy did not write in English.

Nor does Willa Cather make the list, and the list is poorer for it.

Robert McCrum

Robert McCrum

Coda

The pleasure of an exercise like this is that it makes one stop and think, first about the old friends on the list, also about the titles and authors one knows of but has not read. It also introduces new authors and other titles for the reader. Each is welcome.

But most of all it makes one think about the criterion: great.

Is a great novel one that influences other writers?

One that wins readers across generations and cultures?

Is it one that creates an enduring world with its words?

Is it one that leaves an indelible impression of the mind of a reader?

A great novel is one that does such things because there are many, even several, ways to be great.

‘City of Fortune: How Venice won and lost a naval empire’ (2011) by Roger Crowley

Now and again I have had the urge to go to Venice, but never have. To scratch that itch I decided to read a history of the damp republic.

A fishing village on the lagoon is first mentioned in extant chronicles at about 800 A.D. Venice was not a Roman settlement, unlike nearly every other city in Italy today. The mud flats in the lagoon were home to fisher folk who were left alone by others because there was nothing there worth having or worth stealing.

From this embryo grew a mighty city that dominated much of its world for three centuries.

The constant threat of the sea, aqua alta, meant everyone in Venice had to cooperate against nature. That common and constant threat produced a tight social order that put an absolute premium on planning, discipline, and initiative, and most important of all on social cooperation both horizontal and vertical. The commune took precedence over the individual and orders were obeyed.

This is my reading of it because the book is mainly focused on the wars of conquest and decline that led to the empire and then its collapse.

While most European cities between 1200 and 1500 developed an increasingly elaborate hierarchy based on blood, money, and religion, by contrast Venice remained largely undifferentiated with a very flat social hierarchy. That proved a bedrock beneath the water. In this way it seems to me that Venice is comparable to that other muddy republic that lived off trade and battled the sea, Amsterdam. See Geert Mak, ‘Amsterdam’ (2001).

The people of the lagoon had almost no terra firma. That was a benefit since it meant no passing war lord wanted to wade out into the mud to conquer it. It was also a weakness since it meant Venice had to live off trade because there was no vegetable patch. It had to be the broker to live.

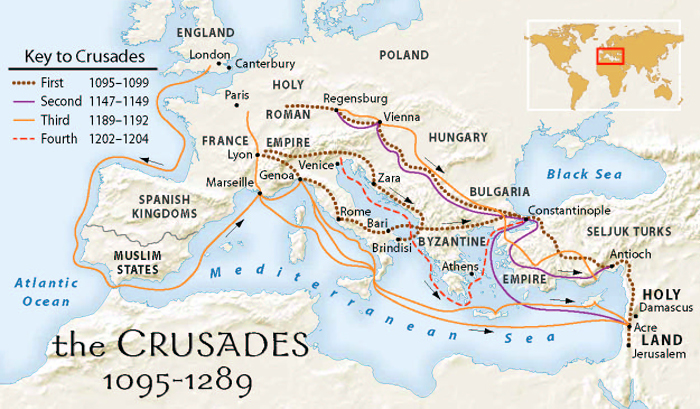

Its conversion from a diet of fish to one of gold began with the Fourth Crusade in 1200 which occupies the first one hundred pages of this book. It is a story for the ages.

The crusades were religious, the aim being to wrest the Holy Land from the infidel, and all those who participated in the effort would be blessed in the Christian heaven for eternity. Sounds like a Holy war because it was.

The first three crusades had limited successes and unlimited failures. They left behind Christian enclaves in the Middle East. Of course, the largest Christian community in the Middle East, as we call it today, were the Greek orthodox Christians in Constantinople. The author refers to that city of the Bosphorus by that name, though at the time it called itself New Rome.

The endless religious schisms in the preceding millennium had divided the Christian world into these poles: the Universal Church in Rome and the Greek Orthodox Church in New Rome. The twain did not meet. At each pole there were further divisions: Two fingers versus three fingers, is one example. (Either one gets it or one does not.)

The Byzantine Empire in New Rome had participated in the earlier crusades, but not as fervently as Popes in Rome thought it should have done. This was another source of friction in the Christian world.

When Saracen leaders in Syria began to squeeze the pimples of the Christian enclaves in Lebanon, the Roman Pope called for a Fourth Crusade to rescue them and to conquer the Holy Land once and for all.

Whereas the earlier crusades had been more or less spontaneous movements of mobs of Christians from Europe to the Holy Land by any and all means, motivated as much by the selfish desire to save their individual souls as to cleanse the Holy Land of Islam in a rag-tag mob of inexperienced, impoverished, undisciplined and diseased hordes who were often unarmed, this crusade was different. The Pope made an effort to organise the Fourth Crusade. by commissioning a number of nobles to lead and manage it.

The plan called for thirty thousand crusaders to be raised, equipped, provisioned, supplied, organised, and assembled in Venice, from whence Venetian ships would transport them to Tyre, Sidon, Beirut, and other ports along the coast of the Middle East. This crusader army would be commanded by Christian lords, barons, and knights from the lands of France, Germany, Italy, and Poland, by and large, though others joined the cause.

An advance party went to Venice to prepare the way. There its members discovered that the Venetians expected to be paid in coin for shipping these souls to the desert. Long and difficult negotiations followed. While Venice had dabbled in sea trade for its living, this project was a hundred times larger than anything previously undertaken. To transport thirty thousand men in a single fleet, along with their arms, equipment, and food, was such a difference in degree from previous trade expedition as to be a difference in kind. Furthermore, a knight must have his steed, and some five thousand horses with grooms, squires, tack, fodder, and more had to be shipped at the same time. Hundreds of ships would be required and thousands of crewmen not he oars and sails.

The Crusaders agreed, reluctantly, to pay 100,000 silver marks, a vast sum equivalent to billions today. The details were many and each was a line-item in the contract, a copy of which remains in the Venetian state archives. Then the Venetians took a year to build the ships, and — once built — agreed on a twelve-month shipping contract to start on a certain day when the crusader army was to embark.

The Venetian Doge, chair of the city council, we might say, though an elderly man over ninety at the time, was keen on the project, and eventually sold it, with all its considerable risks, to the council and in turn to the citizenry. It meant that for a year in Venice all other activities ceased and every citizen of Venice worked on the crusader ships and all that they needed. This focus was enforced by the commune. All of this before a single silver mark had been paid.

The Arsenal became a scene of frenetic activity as ships were produced, logs were imported from Russia along with sail cloth from the England and rope from Estonia. Resources were sucked in and had to be paid for as the work went on and on.

Murphy’s Law applied. Only about a third of the projected number of crusaders arrived in Venice at the appointed day when the meter on the shipping contract started ticking.

The Venetians wanted to be paid, having outlaid nearly all of the treasury to built the crusader fleet and contract the crews, but the crusaders wanted to renegotiate the contract. When the crusaders arrived Venice was more or less broke. But the crusaders did not want to pay for thirty thousand when only twelve thousand had arrived.

Months went by and more crusaders straggled in while others gave up and left. The crusaders camped on mud flats in the lagoon where disease found them. Food was in short supply for everyone. Sanitation is best left in silence.

In the end the Venetians agreed to become participants in a joint venture rather than merely contractors for shipping, this being the only hope of securing a financial return on the massive investment the city had made in the project. They sailed.

It was not plain sailing and they diverted to Byzantium in the New Rome of Constantinople. While the Byzantines welcomed assistance against their Islamic neighbours, they were not keen on an army of thousands of ill-disciplined and increasingly desperate men camped on the foreshore, and still less interested in joining in the crusade. They had had an uneasy but durable modus vivendi with their Islamic neighbours for some time.

Many recriminations followed. Though the Pope had strictly forbade conflict among the Christians on the pain of excommunication, ultimately the Christian Fourth Crusaders attacked and sacked Christian Constantinople. The justification of this Christian on Christian war was as convoluted and tortured as that of a political candidate.

The Fourth Crusade crippled the Byzantine Empire, though it limped on for three more centuries.

Out of the pillage of Constantinople the Venetians got their 100,000 silver marks and another 150,000 for their trouble. While the other pillagers took the money and ran, the Venetians dutifully took the dosh home to Venice, along with much else from Constantinople to enrich Venice. Many of the treasures seen in Venice today, including the four lions on St Mark’s Square, were stolen from Christian Constantinople.

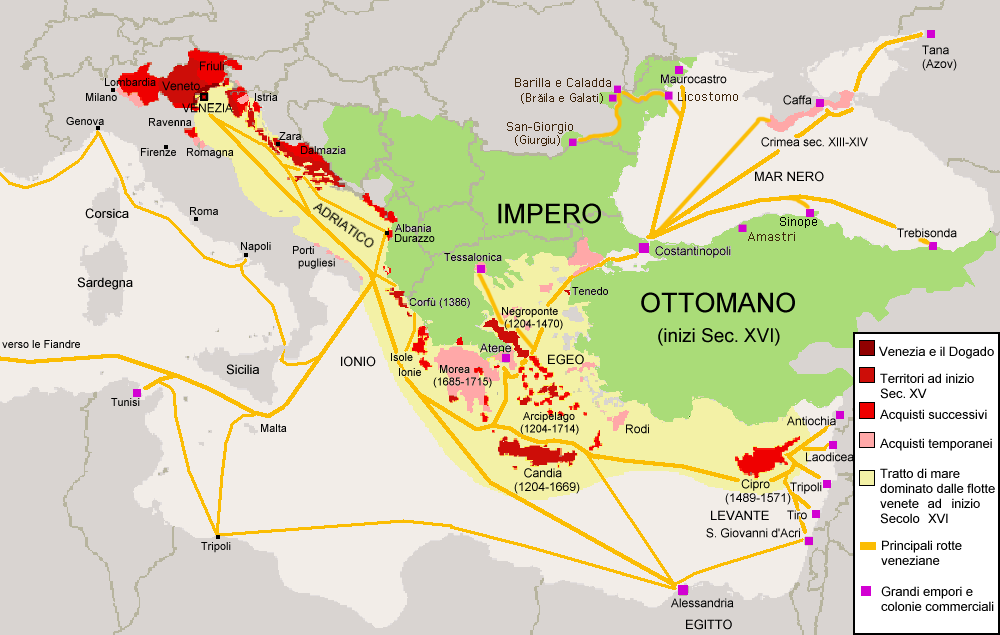

Venice was now the Lion of St Mark, and ruled the waves of the Eastern Mediterranean for the next three hundred years. It had bloody trade wars with rivals, mainly Genoa for a century, but it prevailed partly because of its social cohesion. It established itself on the shores of the Adriatic, Aegean, Azoz, Black, Cretan, Ionian, Levantine, and Marmara Seas.

They established and controlled sea ports, harbours, straits, estuaries, and anchorages, but they did not conquer territory or enslave populations, except on Crete. This empire was a string of settlements along shores under the flag of St Mark dotted along the Adriatic Sea into the Mediterranean Sea and eastward and north into the Black Sea. They never ventured Westward and apart from Venice itself had no settlements on the Italian coast. Nor did they risk the Red Sea to the south.

The red on the map indicates Venice’s empire of the sea.

The red on the map indicates Venice’s empire of the sea.

Venetian citizenship was closed. Venetians were forbidden to marry outside the civic list. Those Venetians who staffed, managed, and ran the empire’s outposts were strictly regulated, as two chapters of the book detail, but the real regulation was social and not legal.

Even while the Christian and Islamic worlds were at war, the Venetians happily traded with both, to the point of ferrying an Ottoman army from Asia to Europe to attack Christian peoples. In so doing the Venetians made a tremendous profit and an enduring reputation for mercenary mercantilism. Shakespeare is downwind of that.

The Silk Road brought exotic luxury goods from the Far East to the Lebanese coast and later to the Black Sea coast, and it is from these goods that Venice made astronomical profits in the high-end market.

Eventually, the Ottomans began to conquer Venetian territories on the Black Sea coast, on the coasts of the Middle East, in Greece, on Crete, in Albania…. Then Venice proclaimed itself the shield of the Christian world and called for a fifth crusade to protect it. Too little, too late.

Used and abused for generations by Venice, other Christians enjoyed the spectacle of Venice supping on its just desserts. In the end Venice bought off the Ottoman but in so doing ceded most of its empire and by 1511 was just another minor city-state as the nation-states of France and Spain became European superpowers. While on a map it retained some marine territories, this was by Ottoman indulgence.

The social cohesion of Venice had disintegrated. In this telling there is no way to know which came first, the social erosion or the defeat. Which precipitated which? There is no doubt that the social discipline failed against the relentless Ottoman abrasions. Individuals enriched themselves first and secreted the money away, sometimes in other cities, like Amsterdam. Other refused to serve the commune and immigrated. While there had always been a few such deviant cases in the past, but in the Fifteenth Century they became the norm.

What finally killed Venice was not Ottoman cannons though they wounded it. Technological innovation delivered the coup de grace. When the Portuguese navigator Vasco di Gama sailed around the Cape of Good Hope to open a direct route to India, Venice’s role as an entrepôt for the Far East, e.g., spices and silk, died within a few years.

Much of the book is devoted to the many Venetian wars with Genoa and the Ottomans and the details of who killed whom in the most creative and diabolical ways. If I want blood-and-gore I can watch the television news where man’s inhumanity to man is on show every night as journalists try to shock without informing us.

The book is well written and impressively researched but did not have the insights into the social, political, ethical, religious, and financial organisation of Venice that I had sought. Many other city-states traded but somehow Venice surpassed them. How it managed, that is what makes me curious.

Roger Crowley

Roger Crowley

Still the book lives up to its title and I can have no complaint.

A few years ago I read Garry Wills’s ‘Venice, Lion City: The Religion of Empire’ (2001). It, too, left me unsatisfied. Wills has shag carpet prose, luxurious to feel, but the book is a litany of one description of an astounding work of art, much of it devotional, after another with little or nothing about their origins and social context. This was a disappointment from an author for whom I had the highest expectations.

My prime source on Venice remains the krimis of Donna Leon and Michael Dibdin.

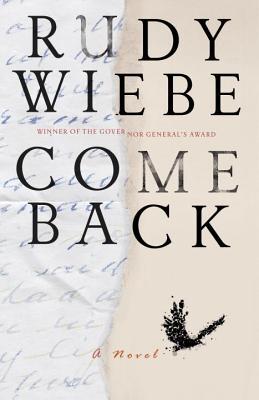

Rudy Wiebe, ‘Come back’ (2013)

This epistolary novel is a meditation on grief and mourning. It is low key, told in fragments and the more powerful for this episodic manner of exposition. At age twenty-five a man commited suicide and his father is thereafter haunted by this death.

Most of the story is told backwards as the father remembers his immediate efforts to understand the suicide by reading and re-reading every word his son left in letters, in noteboooks, in grad school assignments, anything else he can find.

This quest is sometimes played out before a chorus of one, Owl, his Cree, coffee-drinking friend.

It is set in Edmonton Alberta and the characters are Mennonites, very serious and spiritual people, from the vast prairies.

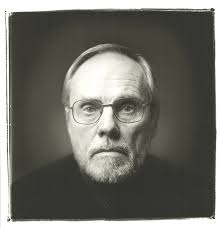

Rudy Wiebe

Rudy Wiebe

I used to see Wiebe on campus in grad school, and read one of his earlier novels at that time, ‘Peace shall destroy many.’ It was memorable. Much of this novel seems near the bone, almost autobiographical.

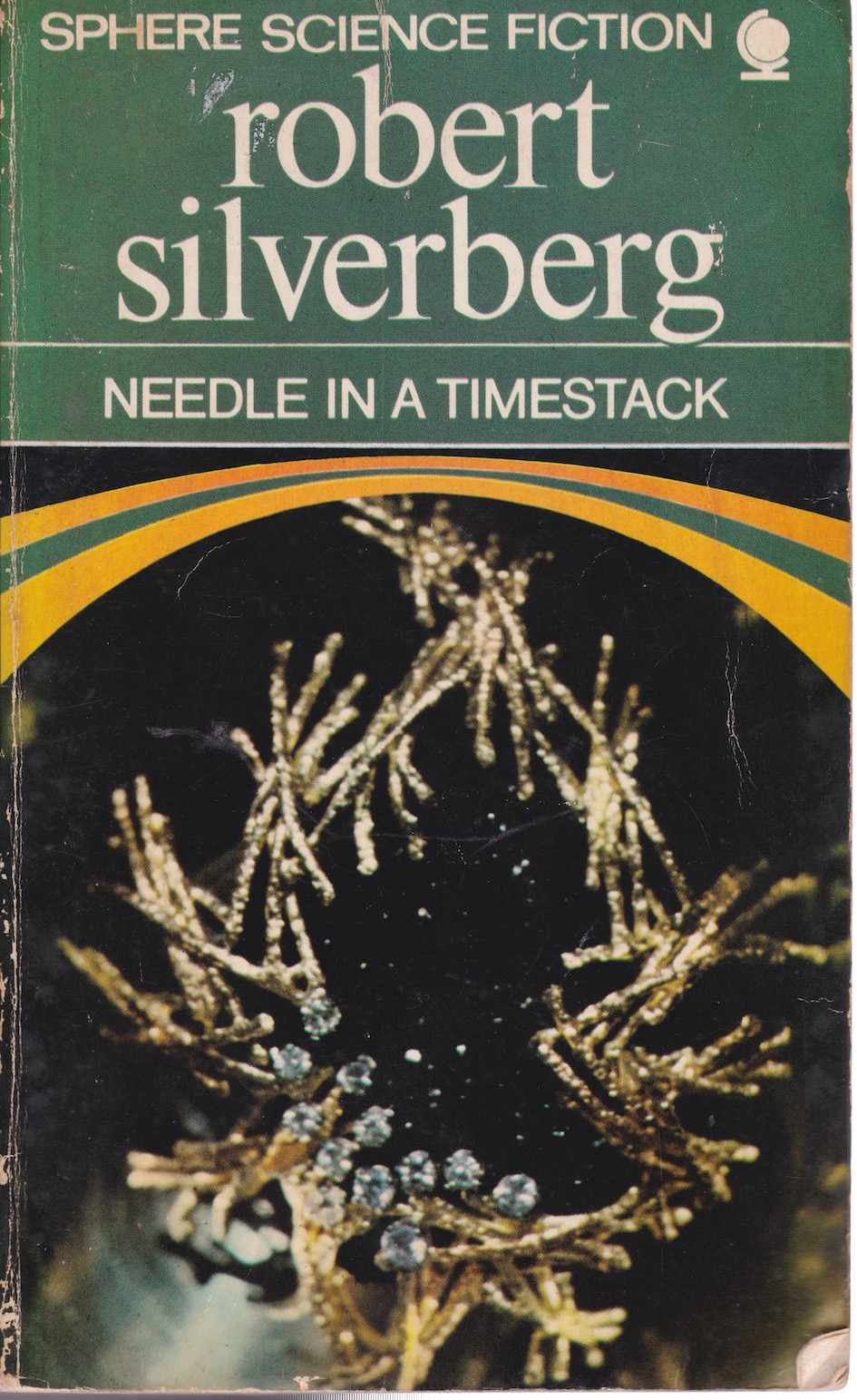

‘Needle in a Time Stack’ (1966) by Robert Silverberg

This title is a collection of science fiction short stories by one of the well-known names in the genre at its peak. In 1966, fifty years ago, a gallon of regular gasoline in the USA was 0.31 cents. Cars had tail fins. Japan was where the junk came from. Vietnam was seldom in the news. The Cold War was very cold. China was …. nearly invisible. Hollywood ruled the silver screen. Air travel was the preserve of the very rich.

Robert Silverberg’s (1935 -) stories feature automatic doors, mobile phones, automatic autos (self-driving cars), surgery that does not cut the skin, video watches, as well as the a menageries of aliens. But mostly the stories are how people think, act, and react. The gadgets are there as props and furniture, as are the aliens.

Best of all, given that in 1966 ‘I Love Lucy’ was the top-rated television show, was his anticipation of reality television with its fetish for the pain and humiliation of others. Equally amusing was the tyrannical robot diet enforcer in ‘The Iron Chancellor.’ Yes, the allusion is to Otto von Bismarck who is here combined with a diabolical Jenny Craig.

The most thought-provoking was ‘The Invisible Man,’ a rift, of course, on the H. G. Wells story but with some social and psychological insight which Wells never had.

The stories are all about 15-20 printed pages. Irony features heavily in them. Think if Rod Serling’s ‘The Twilight Zone.’

A character, usually the narrative voice, is confounded at his own game. The con man is conned. The exploitive television producer is exploited. The lord is abased before a serf. The expert on alien life forms is disgusted to meet one. The firm bureaucrat is dealt with firmly by another. There are quite a few role-reversals.

Most of us like to see the mighty eat some crow. The more so when the mighty are unworthy.

As adventuresome and imaginative as these stories are, a contemporary reader they swim in the manners and morēs of 1966. There is nothing about racism. Not even the stories involving alien beings seem to reflect on race relations.

Alike absent are women. Occasionally there is a secretary in an outer office, or budding young girls who long to be married, or a frazzled housewife, but none is an agent, an actor, These are men’s worlds. The linguist has a wife but her role is to pack his bag when he goes to meet the aliens. The doppelgänger meets several young women whose only aspiration is marriage. The dieting husband has a wife who also needs to diet, but she is but a chorus to his tenor.

Sometimes the balance of the stories fails. There is a considerable lead up to wispy, poof denouement.

The prose is fluent and confident. I re-read a couple of Philip K. Dick novels a few years ago and remember finding it hard going. Not so with these pages.

Most collections of short stories take the title from one of the stories, usually the longest or the one placed first. That is not the case here. The title stands apart.

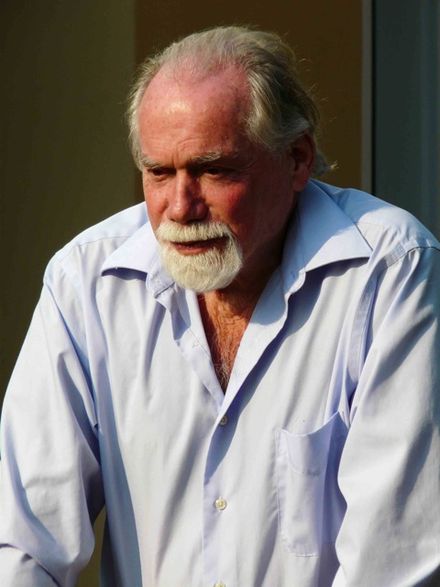

Robert Silverberg

Robert Silverberg

This copy emerged from a box in our recent move. Kathlyn McNeil bought it for 0.80 cents Australian in 1966. In those days the back cover had prices of Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, South Africa, and East Africa. Its pages have yellowed but the paperback spine remains bound.

Ryszard Kapuscinski, ‘The Soccer War’ (1986)

A unique journalist this, as Poland’s one and only foreign correspondent for many years he covered the world of Poland’s allies in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. His extended essay ‘The Emperor’ (1989) on the reign of Haile Selassie in Ethiopian is nonpareil.

The insights, the wit, and desiccated humour all stay with the reader long after. Though much of it is fiction larded with a great deal of speculation it makes sense in a way the description of facts and furnishings does not.

The essays in his ‘Travels with Herodotus’ (2002) are likewise memorable. This volume is much more thematic than the compilations of his journalism in other titles. The focus here is on history and the recording thereof.

When ‘The Soccer War’ came to light among the book boxes at home I put it aside to peruse, and peruse I did. (We are still unpacking after last year’s move.)

Most of the places and events in these essays are unknown to me. I never heard of them at the time, or if I did, the memory faded at day’s end. But Kapuściński went where Poland supported insurgents, governments, or had economic interest in the nooks and crannies of the Cold War. He travelled, as he remarks elsewhere, Polish-class. [Use the imagination.]

The Soccer War was a three-month armed conflict between El Salvador (the Switzerland of Central America) and Honduras, then a brother-in-arms with Poland in the Socialist International. Though the animosities and tensions between the two countries were many and deeply rooted, the war exploded when the two played soccer for a place in the World Cup in July 1969. These two midgets were deadly serious, and several thousand people died, and tens of thousands more were displaced. In the aftermath social services collapsed in both countries and many more died of disease and untreated illnesses.

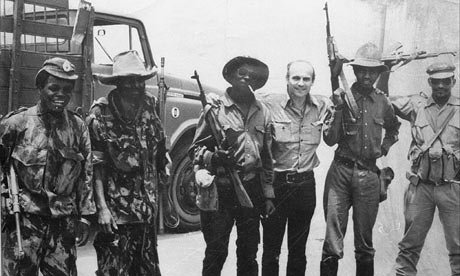

Kapuscinski with some comrades.

Kapuscinski with some comrades.

Kapuściński happened to be there and became an eye-witness, though he hardly saw anything, try as he might. Think of Fabrice at Waterloo in Stendhal’s ‘The Charterhouse of Parma’ (1839). Add jungles, swamps, and a language barrier.