A unique journalist this, as Poland’s one and only foreign correspondent for many years he covered the world of Poland’s allies in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. His extended essay ‘The Emperor’ (1989) on the reign of Haile Selassie in Ethiopian is nonpareil.

The insights, the wit, and desiccated humour all stay with the reader long after. Though much of it is fiction larded with a great deal of speculation it makes sense in a way the description of facts and furnishings does not.

The essays in his ‘Travels with Herodotus’ (2002) are likewise memorable. This volume is much more thematic than the compilations of his journalism in other titles. The focus here is on history and the recording thereof.

When ‘The Soccer War’ came to light among the book boxes at home I put it aside to peruse, and peruse I did. (We are still unpacking after last year’s move.)

Most of the places and events in these essays are unknown to me. I never heard of them at the time, or if I did, the memory faded at day’s end. But Kapuściński went where Poland supported insurgents, governments, or had economic interest in the nooks and crannies of the Cold War. He travelled, as he remarks elsewhere, Polish-class. [Use the imagination.]

The Soccer War was a three-month armed conflict between El Salvador (the Switzerland of Central America) and Honduras, then a brother-in-arms with Poland in the Socialist International. Though the animosities and tensions between the two countries were many and deeply rooted, the war exploded when the two played soccer for a place in the World Cup in July 1969. These two midgets were deadly serious, and several thousand people died, and tens of thousands more were displaced. In the aftermath social services collapsed in both countries and many more died of disease and untreated illnesses.

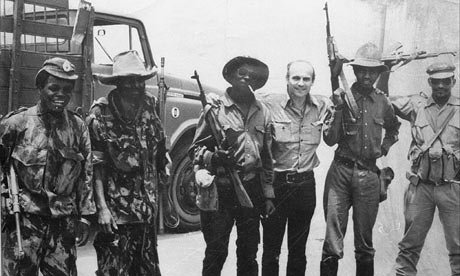

Kapuscinski with some comrades.

Kapuscinski with some comrades.

Kapuściński happened to be there and became an eye-witness, though he hardly saw anything, try as he might. Think of Fabrice at Waterloo in Stendhal’s ‘The Charterhouse of Parma’ (1839). Add jungles, swamps, and a language barrier.

Category: Book Review

‘The Readers of Broken Wheel recommend’ (2016) by Katarina Bivald.

Chick Lit and I want more of it!

A delightful account of the culture clash between a single Swedish tourist who comes to Broken Wheel, Iowa, population 640 and declining. Sara is her name, and though she is classroom fluent in English the Iowa accents and idioms do not readily translate.

The good citizens of Broken Wheel are delighted to find a tourist in their dwindling midst. Sara left Sweden because there was nothing there for her, and she is pleased to be warmly welcomed.

Sara, however is nonplused, because her pen-pal and prospective host for the stay in Broken Wheel, Amy, is nowhere to be seen. She and Amy have been corresponding about books and life for a long time. The absent Amy has left instructions that Sara should stay in her house and make use of her books. She does.

Caroline runs the town by the force of personality. Formal positions mean nothing, and in the end that pays off, but not before this pillar of rectitude learns herself of sin first hand. Wow!

Jenn chronicles it all in her newsletter, blog, and private diary. Grace observes with disdain, a shot gun at the ready. The Grace women are always armed.

George stays off the drink one day after another, that is, until his long lost daughter returns, and then leaves again. The second loss is too much for George.

Andy and Chris pull the beer at the tavern, and the six hundred residents accept this gay couple without a word.

Cornfields play a part, too, because after all it is Iowa; there are a lot of cornfields, but none as scary as the one in the first episode of ‘Star Trek: Enterprise.’

Spot the Klingon.

Spot the Klingon.

Then there is handsome Tom who cannot help noticing the new face in Broken Wheel. He is too handsome for her, and she is too smart for him, but, well, in books anything can happen, right Mr Darcy?

Then Gavin the regional representative of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service appears. Gavin hated his old job in the USCIS because he had to arrest and deport hard working, god-fearing, polite, resigned, clean, and illegal Mexicans who never complained about how badly they were treated.

His remit is now Europeans, and Sweden is in Europe, right? Europeans, these he is ready and willing to arrest and deport for the slightest infraction of visa rules. If only…

Gavin descends on Broken Wheel with the full might of Federal government at his disposal, and finds that he is overmatched against Caroline.

Katarina Bivald

Katarina Bivald

To give the devil its due, I noticed this comment on Good Reads

‘This book was absolute rubbish. 394 pages of stupid observations written in a clumsy and somewhat childish language combined with unbelievable characters.’

A salutary reminder of why I do not bother with Good Reads.

‘Lanterne Rouge’ (2013 ) by Max Leonard

Lanterne Rouge? Yes, it can be the red light on the last car in railway train, in the dark there to let yardmen, roustabouts, and switchers know that is the final car. It can indicate a doctor’s late night surgery in some countries, and…., well, you know. (I only know from movies.)

In this case, none of the above!

The Lanterne Rouge is the last rider to finish the Tour de France, and Max Leonard, himself a cyclist, wondered how those losers felt about being last.

I am glad he did, because their lives, races, and attitudes are varied, intriguing, and represent much of the Tour de France at its best and at its worst. Moreover, Leonard has a light touch with self-deprecating humour, as he rides them down.

Perhaps the most important point made is that to finish last in the Tour de France is not losing!

Counter-intuitive, but true all the same.

When one Spanish rider was asked by a boneheaded journalist, is there any other kind, how he felt about finishing last, this was his reply: ‘One hundred and ninety-eight riders from the cream of world cycling started the Tour and I finished (stress, finished) at 120.’

Explanation: Seventy-eight others did not finish, but he did. To do so he had to make the time cutoff each day to stay in the race, not easy that, period. He coped with mechanical breakdowns and stayed in the race. He managed injuries from falls and stayed in the race. All the while he performed his role on the team, carrying water bottles for others and pacing the sprinter. He climbed the mountains in the Pyrenees and the Alps, endured the individual and team time trials, pedalled the long flats, and coped with the weather. Hard. Hard. Hard.

It is a theme that recurs. Finishing is itself a triumph, over the elements, over the odds, and over one’s own weakness, capped by a roll down the Champs Elysee with family and friends on the sidelines among the 100,000 spectators and millions more on television!

Sometimes it is a triumph over injury, as one Lanterne Rouge rode the last eight days in a neck brace, others with enough stitches to bring tears to one’s eyes. All of them overcame the inner voice that urged them to quit on the slope of L’Alpe d’Huez, half-way through a 60-kilometer time trial, while riding last through a parallel rain storm off the Atlantic, or on a hairpin-turn descent. For many it was the dream of lifetime fulfilled to ride in the Tour and to finish. Period.

Further proof, be it needed, is in the person of Jack Durand, who finished last and yet stood on the winner’s podium on the Champs Elysee! Huh? He was awarded the medal for the Most Competitive Rider.

Through the three weeks of the Tour he led one attack after another, on climbs, in the flat, against the wind, through tunnels, often alone. On some days he led the field for a 50 kilometres. Some of breakaways produced a gap of 12 minutes. Some days he pedalled quietly in the peloton. He was unpredictable and explosive. His post mortem was this: ‘Everyday I ride to win. Against such champions as gathered for this race, I have to beat them mentally with breakaways.’ Indeed he did win a stage in that tour.

Then there is Phillipe Gaumont who became a (barely) riding chemistry laboratory. He surrendered to Dr Alchemy, and rode on Belgian Pot, a concoction of cocaine, blood stimulants, and anything else lying around the laboratory. As he slowed down, he took more needles, the syringes taped to his ankles inside his socks. The effect was curvilinear, at first he was stronger, then he plateaued, and then he slowed, as he slowed, he shot up ever more drugs in the hope of regaining speed, but instead that slowed him down even more and he could barely finish. Thereafter he broke down, and shortly thereafter told all in a memoir. He died at 44, surely the chemical soup hastened the end.

Max Leonard

Max Leonard

These stories illustrate the material. In its one hundred editions, there has always been a Lanterne Rouge, and there are more of their stories in the book. There are many ways to be a lantern rouge in life and it does not mean being a loser. There is a moral in there somewhere.

Why context counts. Edward T. Hall, ‘Beyond Culture’ (1976)

The distinction between High and Low Context is a valuable tool. It can be applied at many levels to social interactions. I fastened on to this distinction because it explains much about the writings of Niccolò Machiavelli. He was a high context writer. That is one reason why I bristle when I see his themes applied to … well almost anything since his death.

To illustrate in broad, within a nuclear family speech is often cryptic, because both speaker and auditor are entwined in the same context which itself communicates much through the accumulation of experience.

When Kate says, ‘It’s Thursday,’ I know she means it is time to put the wheeled bins of recycling and rubbish on the street to be emptied early on Friday morning. She does have to say, ‘It is time to wheel out of the garage the red-lidded and yellow-lidded bins, one at a time, because it is tight squeeze past the car, to the front of the house near the curb facing backward for the mechanical arm to lift onto the bracket on the truck…..’ Her shorthand is very clear to me, but has been incomprehensible to house guests.

Some years ago we prepared a manual for house-sitters who move in while we travel, and in writing and illustrating that manual we assumed low context, and explained and spelled everything out from the location of spare light bulbs, to the vagaries of Wi-Fi, to the operation of the garage door, the use of Netflix, the way the lock works on the back gate, to the nights when the bins have to go out, and so on and on. The manual will soon be a multi-volume work because, lacking context, it is explicit and detailed about everything.

For those still not convinced that context matters, consider the array of remoters that lie around the tele, video, and music devices at home. Their use and interaction has been learned by users, but is far from obvious to a neophyte. While I can operate our system, barely, there is no chance I can do so with someone else’s without guidance, instruction, or a manual.

More generally, in the state of Nebraska everyone is a Huskers football fan, most volunteers, some conscripted, and every Sunday with friends and family, and every Monday with colleagues, there is a postmortem of each Saturday’s game in the season. It may start with a remark like, ‘Thomson has got one powerful arm.’ The auditor is assumed to know whom Thomson is, what the reference is to, perhaps a sixty yard Hail Mary touchdown pass in the waning moments of the game, and more. Nebraskans will forgive outsiders for not knowing all of this context, but for one of their own not to know, worse, not to care, is beyond the pale.

This distinction between high and low context explains a lot about the natives described in Colin Turnbull’s ‘The Forest People’ (1961), one of the most fascinating books I have ever read. But when I read it, I did have this tool in mind. This is a book some may remember from the ‘Power’ course in days of yore. Time to read it again.

I see the same distinction between assumed context in philosophers. Some wrote for a wide audience and spelt out first principles, like Plato or John Locke. Others wrote for a known and limited audience and were cryptic like Georg Hegel writing text notes for his students. Others wrote for and to themselves, like Niccolò Machiavelli. Hegel and Machiavelli, in particular, are high context writers, while Locke and Plato are low context.

The chapter on this distinction is about ten pages long, and is to be found in the middle of this book. For me it is the most valuable part.

Much of the rest is punctuated with Hall’s asides on his personal experiences, his previous research projects, and even hearsay. Some may find these touches humane and interesting but this reader found them self-indulgent and padded. Hall is an anthropologist.

Edward T. Hall in 1966

Edward T. Hall in 1966

Irony is never far away is it, Mr Spock? The author is a sensitive canary to the vibrations of all manner of cultures, remember those personal experiences, but he writes only of ‘man’ and ‘men.’ Even in 1976 that would have caught the eye.

William Dietrich, The Trojan Icon (2015)

This is the eighth outing for Ethan Gage that energetic Eighteenth Century rogue. While I have enjoyed most of the books in the series, once again I had the feeling that the the wind is leaving Ethan’s sails. This title is much slower and more serious than its predecessors. Ethan does not sparkle. He worries a lot. The word ‘again’ refers to ‘The Emerald Storm’ (2012) which seemed more a forced march than a romp.

![]()

Moreover, the narrative is divided between Ethan and Astiza, his wife, and she is even more serious than Ethan has become because she worries about their son Horus (Harry) who also has some chapters, consisting chiefly of him worrying about his mother. There is a lot of worrying. These three worry enough to be Op-Ed writers, that professional worrying class.

The technique of alternating chapters with the voices of Ethan, Astiza, and Horus slows the pace a lot. And it is distracting. Especially Horus, the eight year old whose range is, well, that of an eight year old.

On the other hand there are vivid characterisations of the many individuals and the places that Ethan meets and traverses but once again it was too much, St. Petersburg and the Russian court, Poland and a revanchist noble, Istanbul and the the harem in the Topkapi. Indigestion, I cried. All of this name and place dropping is not a substitute for élan, spirit, movement, and fun.

Yet for all the movement there is none of the pace that I have so enjoyed in some of his earlier titles in this series. In these pages the movement is punctuated by long periods of rest and relaxation. and, of course, worry.

One character drops out of the story half any through, namely the Russian prince, whom I keep expecting to re-appear, as others do in this novel and have in the others in the series, else why have him in the first place. Answer: a plot device.

It is peopled with some truly malign villains, von Bonin and Count Dalca. Neither one is a quitter, that is for sure.

The eight Ethan Gage novels.

1 Napoleon’s Pyramids (2007)

2 The Rosetta Key (2008)

3 The Dakota Cipher (2009)

4 The Barbary Pirates (2010)

5 The Emerald Storm (2012)

6 The Barbed Crown (2013)

7 The Three Emperors (2014)

8 The Trojan Icon (2015)

I found ‘The Emerald Storm,’ despite its exotic setting, to be forced as I found this title to be. I read this one on the Kindle. I do hope the author consults Alfred E. Neuman before he writes the next one follows Neuman’s timeless advice ‘What, me worry?’

Barbara Pym, ‘An Academic Question’ (1976)

Another gentle comedy of manners set among the red bricks of an English provincial university. Our heroine is Caroline, Caro, and her husband Alan Grimstone, who is a lecturer in anthropology at the aforementioned university. The social manners and morēs are very 1950s, though the time is the 1960s. The women are wives and the wives are housewives. Only widows and eccentrics are permitted to be exceptions.

Caro has little to do. Even less than some other faculty wives, because Alan does his own typing, in part, because he is secretive about his research. He is in competition with Professor Crispin Maynard who is head of his department in a narrow field of study, or so Alan thinks. The professor is more concerned with his grandchildren and dogs than with off-prints.

To fill in her days Caro reads to inmates at a nursing home, to call it by its right name, and one of them the Reverend Stillingfleet spent many years in Africa where he wrote notes about the natives’ manners and morēs. By using Caro’s reading as cover, Alan snitches one of Stillingfleet’s notebooks. It contains valuable data which he immediately incorporates into a journal article manuscript, the argument of which undermines the professor’s own work in the field.

Alan does offer the professor the opportunity to read the draft manuscript, but what with grandchildren and dogs, he declines. The clouds gather.

While Alan and Caro are still in possession of the notebook, Stillingfleet dies. Returning the notebook nows seems impossible so Caro keeps it, and Alan acts as if he does not know that, though of course he does.

Alan submits the manuscript and, voilà, it is accepted. If only it was ever that fast and easy!

He goes to London to correct the proofs to speed the process even more.

Caro moons around, wondering what to do with herself. She does not want a part-time job at the university library, which Alan thinks suitable, because she does not like the people in the library. She considers work in a jumble shop, but Alan does not find that suitable. This is a time and place when women often were introduced as ‘Mrs. Alan Grimstone,’ without even their own given name being, well, given.

She wonders if Alan is unfaithful to her, since he is often out at nocturnal seminars, and those trips to London to correct the proofs do go on. There are temptations in Iris, Inga, and Cressida.

She has some friends but they get on with their own business. Coco, Kitty, and Dolly, each seems to have a better grip on reality than Caro and they do buck her up from time to time. But well, Coco is a man who is apparently asexual, and with his mother, Kitty, together mentally they still live on the Caribbean island surrounded by servants as they were when Kitty’s late husband was governor, and so they are not entirely reliable. There is ever so faint an indication that Coco is homosexual. Dolly, who is Kitty’s down to earth sister, is the most practical person in the book, but she is rather obsessed by the life, loves, and deaths of the hedgehogs that inhabit her rambling garden. Any personal confidences shared with her inevitably are compared to the doings of the hedgehogs, which Caro finds rather…..

Alan admits a dalliance in London with Cressida, and expects their life to continue as before. He is man of his time and place, he cannot make tea, make a bed, prepare toast, etc. After retreating to stay with her mother and then sister a few nights, Caro returns to Alan and nothing more is said of the dalliance. Stiff upper lips and all that.

Alan’s paper is published, Maynard writes a rebuttal. Stillingfleet’s manuscript is lost to an accidental fire in the library to which he gave his papers, but the war of words between Alan and Maynard goes on in the pages of the journal, while they invite each other to tea at home and talk of the seasons. All very civilized.

Along the way, Alan asks Caro to do some typing for him, and she greets this as bridge between them. She will now be permitted to help him and take an interest in his work. He means it that way, and she takes it that way. I took it as satire.

Caro returns to the nursing home to read to others, and finds another elderly person with a trunk of papers….

There is a reference to Miss Clovis from Pym’s earlier novel, Less than Angels (1955). Some incidents seemed to set up for development in later novels, but this was her last.

Barbara Pym at the typewriter.

Barbara Pym at the typewriter.

The telling probably deadens it but in the reading it is light and breezy, and any members of a university or college department will recognise the types, the ambitions, the moans and groans of a nine-hour a week work-load, the quiet desperation of some women to breath in the manners and morēs of the time and place, the restive students….

Väinö Linna, ‘Under the North Star’ (1959)

One of the classic sagas of Finnish literature detailing life in a village in the period 1884-1907 as a microcosm of Finnish history of the period, which I read as homework for our planned short visit to Helsinki in September 2016.

It is earnest and documentary in style. We start with Jussi who works hard as the handy man at the parish manse and in his spare time drains a swamp, and with the verbal agreement of the vicar farms it.

All readers know, as Jussi suspects, that the verbal agreement will be insufficient when tested.

Much of the book is like this. It sets up situations that any reader can see unfolding.

The message is clear, the underclass always takes it on the chin, and the underclass is always Finnish, and even if the overclass is, in the village of Pentti’s Corners anyway, Finnish they hold the position because of Russian suzerainty of the Grand Duchy of Finland.

The language politics pervades all. The old vicar preaches in Russian and consoles the bereaved in Finnish. The local newspaper is in Russian. Finns are seldom permitted to speak Finnish.

Legal questions, like Jussi’s informal tenancy, are adjudicated by Russian law, not Finnish practice. Nor even by the rules of John Locke, i.e., ownership going to those who mix their labor with the land, which in this case would by Jussi.

A young vicar replaces the old and in time the pressure on his young family is resolved by encroaching on Jussi’s farm. The vicar’s wife is the source of this pressure, and she is a cardboard cutout for this role.

Indeed, none of the characters are rounded. Jussi is nearly a robot, who works all day and all night. Though he is credited with the vision to realize the swamp could be drained and farmed, that seems to be limit of his imagination, and that limit is enough for the plot. A little too pat, I thought.

Likewise, the other characters stereotypes from many other such stories, the talented and handsome workman who prefers to lay around scheming his next seduction, the vodka soaked doctor, the fiery tailor who speaks a garbled version of proto-Marxism from Georgi Plekhanov about the masses, the timid newspaper publisher who dares not print a word of Finnish for fear of losing the licence to publish.

The Japanese defeat the Russians in the Far East, and though not a word is said of it by any official source, and not a word published about it, still everyone in this remote village knows it. Yes, I know about rumour mills, but really, most of the unschooled people in the village Linna has conceived would have no idea of the Far East or Japan.

There is also political unrest in Helsinki, including an assassination. While this is closer to home, it is still an alien world to the villagers, whose major worry is retaliation from the Russians. Rational as that is, it also seems a long bow for these rough, uneducated villagers to see cause and effect in this way with the goings on in distant Helsinki where none of them, and no one they know, has ever set foot.

The tailor Halme agitates and the vicar counsels patience. Those locals who are aware of some of the wider world suppose that if the czar only knew how badly the Finns were treated, then he would change things. This is the old Russian folk maximum, perpetuated by every czar. The bad comes from corrupt ministers around the czar, that insulation that kept the Romanovs in business for the last hundred years. (Spell checker note: ‘czar’ is a difficult word to get through the spellchecker. It would prefer tsar so I stubbornly persisted with czar.

When Russia revoked its commitment to a Finnish Constitution, there was a reaction in Helsinki and nationalists adopted some proto-Marxist rhetoric to organised resistance. Some of the youths who resisted were exiled and made it to Queensland in northern Australia, as chronicled in the novel of Craig Cormack ’Kurikka’s Dreaming’ (2000). Russia itself was undergoing severe strains at this time, too.

Marx was right and Plekhanov was wrong, by the way, and the villagers do not arise to seize their the fruits of their labor. Although Jussi’s son Akseli becomes a convert to socialism and that makes him a marked man. While there is no general strike, but there are plenty of strikes here and there. The natives are indeed restless and Halme continues, making suits for the squires, while agitating for a mix of nationalism and socialism, one does not dare say national-socialism any more.

There are divisions among the Finns who are united by nationalism and divided by ideology. Numerous variations are traced in debates, speeches, rallies, and confusion.

The first time the people of the village see a Russian, he comes to nail up a notice filled with threats. Not a public relations master stroke. This followed shortly thereafter by evictions enforced by mounted police who are Finns but labeled Cossacks. It is a common motif that overwhelming force will shock and awe the restive into submission, and it never works, leading to ever more force, as it does in these pages.

Though I found the novel stiff and wooden, it is also true that the author knows the way of life of the people he depicts better, say, than the social realist writers in the United States covering the same period. I have in mind Theodore Dreiser, Frank Norris, and Sinclair Lewis. There is in Linna’s pages none of the condescension that Dreiser, Norris, and Lewis unwittingly reveal while representing the downtrodden. While loud in denouncing the oppressor such writers have no empathy with the oppressed. Their reaction is intellectual, learned from the pages of books. Linna’s voice is much more authentic than any of these three.

There is no redemption for the novel in the descriptions of that north star or nature and the place: these are mechanical. I found only one playful mention of Swedish, albeit I was turning the pages very fast, but ethnic Swedes remain to this day, an exclusive caste in Finnish society, as evinced by the Finnish literature written in Swedish.

Väinö Linna

Väinö Linna

I glanced at the many laudatory reviews on Good Reads and found nothing in them to give me pause. This is volume one of a trilogy and I think I will leave volumes two and three to all those accoladers on Good Reads. Serves them right!

Madeline Miller, ‘The Song of Achilles’ (2013)

This is the story of the boy Achilles and lifelong companion and true love Patroclus from their first meeting when both were eight, told from the point of view of Patroclus and set in a mysterious world. It is ‘mysterious’ because the gods are ever-present. Max Weber said the Enlightenment had gradually ‘demystified (Entzauberung) the world,’ that is, taken the mystery out of the world through rationality and science. Well, this novel is firmly set in a world that has not been demystified. The author handles both the gods and the men and women and the goddess, if that has to be said, quite well, and also their interactions. The prose is gorgeous and the conceptions of the principals is engaging.

I made the remark about goddesses because anyone familiar with the mythology knows that Thetis, the divine mother of Achilles, was one formidable goddess. Even the the king of the gods, Zeus, had been known to steer clear of her.

Patroclus is a foundling who pitches up at the home of Achilles’s mortal father, who takes in boys as future warriors. In a world ruled by the sword this is a wise precaution.

We visited the site of Troy in October 2015.

We visited the site of Troy in October 2015.

The view of the Trojan plain.

The view of the Trojan plain.

The descriptions of Achilles from boy to man are, well, Homeric, it has to be said. He is beautiful, he is graceful, he is simple in manner for there is no need for him to prove himself to himself or to anyone else, his senses are preternatural… he may work all day with sword and spear in practice and yet never seems to sweat. The abrasion of his hands on sword haft never raises a callous, and so on. Truly he is favoured by the gods.

The more so when Thetis appears, as she does, now and again and when least expected. The first time she appears to Patroclus, of whom she disapproves as unworthy to be a companion of the god-born Achilles is marvellously realised. (Ditto the last time.) The boy is walking along a mountain path when he realises all has gone quiet. The cicadas have stopped. The birds have left the sky. Even the leaves on the trees are still. The grass itself seems tense in expectation. And then…there she is, a combination of incredible beauty and searing hatred. To look at her burns his eyeballs, when she looks at him, his skin burns. Not a goddess to cross.

Though Thetis hides Achilles to spare him from the Trojan War, the wily Odysseus finds him. That is another story and it is partly re-told here afresh. She hid him among a large group of girls in female attire. Suspecting that Achilles was among these girls, Odysseus threw down a sword before them and the hand that snatched it up with blinding speed, that was the hand of Achilles. He was born to hold that sword, a reflex to grab it. The story is dressed up a little here but stays entirely faithful to the legends. Odysseus used some good old fashioned leg work to find the place where Thetis had secreted her darling boy before he got close enough to drop the sword.

There are some soft spots in the story. It is never clear to me why Achilles took up Patroclus. Achilles is asked this very question a couple of times and answers each time, but none made sense to this reader.

I also found it hard to reconcile this mild mannered Achilles with the butcher he became at Troy. Though the novel does deftly lay the groundwork to explain his double reaction at Troy, first to the loss of the girl Briseis to Agamemnon and then Hector’s murder of Patroclus. Though, strangely, regarding Briseis the author does not quote what Achilles says in the ‘Iliad,’ ‘I love her.’

Yes, Achilles knows the doom that hangs over him, and in time Patroclus learns it, too. But there is a shred of hope even amid these Western Front trenches at Troy, for the prophecy says that as long as Hector, the Trojan champion lives, so shall Achilles, i.e., Achilles will only die after Hector. Since Hector seems indomitable, Patroclus has hope that Achilles will survive, somehow. Patroclus is not a deep thinker.

Achilles faces his destiny and wades into the mayhem at Troy slaying this one and that by the dozen. He moves at five times the speed of even the most athletic opponents. Patroclus, never much a hand at athletics or warfare, stays clear of the fighting and becomes a healer, and there is much to heal. This I do not remember from the ‘Iliad.’ But the author made a choice for reasons of plot and character. So be it.

More than once ethical and moral matters rise to the surface, and are discussed by characters. The writer manages to do this without anachronism, not imputing to these men and women our Enlightenment ethos, nor condemning them for lacking it. Quite an achievement, this. Those that have not read the ‘Iliad’ do not realise how philosophical is that poem of force.

But fate is fate, and bad leads to worse.

Madeline Miller is a high school teacher.

Madeline Miller is a high school teacher.

The novelist clearly shows that, to a degree, even within the ambit of the prophecy, Achilles is the author of his own fate. That is an achievement. Chapeaux!

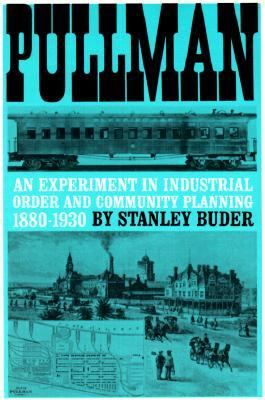

Stanley Buder,’ Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning, 1880-1930’ (1967).

When doing homework for our trip to Chicago I came across reference to Pullman railway cars, a fascinating business model in itself. Those references also mentioned George Pullman’s artificial community, the eponymous Pullman. It was time to find out more.

Pullman made a fortune from the railway cars that bore his name from 1867-1968.

George Pullman.

George Pullman.

As railroads were rebuilt after the Civil War and extended coast-to-coast, Pullman built ever more of them and had to expand the manufacturing capacity. Because in his business model the staff of the cars was also contracted with the cars (of which he always retained ownership), he also had to recruit and train staff to maintain the Pullman standard. To do so, he bought more than 4,000 acres south of Chicago and set up a new factory and built a town around it.

To recruit first class mechanics (the term that applied to all skilled workers in his factory), to ease the commute of workers who lived in Chicago, and to satisfy his philanthropic self-image he built a community for his workers called Pullman, after the factory, not after him personally in the first instance. It would offer all the necessities and conveniences of town life from clean water, sanitation, paved streets, schools, libraries, theatres, and so on, all laid down in a plan and built before the first inhabitant moved in. There were would be no demon rum, no gambling, no prostitution and related vices.

The dwellings were varied in size and the occupants rented them from the Pullman Company at a rate calculated to return 6% on the investment of building and maintaining the community, that being the return the Pullman Company realised on its other investments. This return was important because Pullman wished to prove to other robber barons that such social investment was profitable. The author found that it never did quite make 6%, more like 4.5%, something that the Pullman Company kept secret.

Pullman employees had first priority for the housing, but some others also rented there though not many because there was nothing there but the Pullman factory in the early days. The homes were subject to occasional inspections to identify maintenance needs and to insure that the occupants were taking care of them. At first the rent was extracted from salaries before they were paid, but a court struck that down in a class action. Nonetheless when paid, Pullman employees could not leave the pay desk without paying the rent.

What’s so good about utopia? The town of Pullman offered peace and quiet, recreation for families (parks, theatres), libraries and schools, sanitation, clean water, fuel, and the like, all laid on. It was run by a business manager because it was unincorporated. Ergo the residents had no say whatever in what happened. Moreover, their residential tenure depended on the Pullman Company. Furthermore, they could never buy a home there. By the way, the community included a covered market but Pullman did not have a company store, but rented space in the market to providers.

It is a kind utopian thought experiment. One can have all these good things of life in return for giving up democracy.

George Pullman was no friend of democracy, having observed at first hand its practice in the 1850s and 1860s in Chicago where one corrupt political party replaced the other by turns with mayors and councillors each more venal than the other. The corruption at city hall, ensconced by the democratic process, was matched by the drunkenness, robbery, assaults, prostitutions, and drug-taking on the streets. One neighbourhood of two thousand residents had forty bars and fifteen brothels, and more. Ruthless landlords built tenements and extracted maximum rents for rat-infested hovels. Despite the taxes collected, the streets were mud baths with plentiful horse droppings. Schools and libraries were private with stiff fees. But here was vigorous democracy as the parties battled each other in the race to the spoils. The corruption included wholesale vote rigging. Some things have never changed in Chicago. There has always been a high turnout of voters there, especially among the dead who do not care for whom their vote is cast.

To most residents of Pullman and to the journalists and philanthropists who visited the town, it was superior. ‘To most’ but not all, because some railway workers wanted to extend the union to Pullman workers to secure higher wages and to increase the security of tenure in the homes they rented. There were occasions when workers who did not meet the Pullman Company standard of punctuality, sobriety, and good work were evicted from their homes overnight. In least one case the activities of a worker’s wife caused eviction. (Use you imagination to figure it out, Sherlock.)

George Pullman reacted to these union stirrings as a personal affront to his benign paternalism. There would be no negotiation; not an inch would be given. Cometh the fall.

The railroads were the site of much of the early struggle for unions, often led by the redoubtable Eugene V. Debs. I have discussed a biography of Debs elsewhere on this blog.

At the same time the ever-expanding city of Chicago, doubling in population every ten years, was encroaching on once distant Pullman. In time Chicago incorporated Pullman into Cook County though leaving the domination of the Company largely intact for another decade.

The collision course was laid in. The Pullman Company paid high(er) wages to attract and keep good workers as well providing all of the amenities of Pullman town for them and their families. But it was a business and when competition undercut the Pullman Company it unilaterally reduced wages while leaving the rents at the established level to get that 6% return on investment. When demand was high it expected unpaid overtime out of corporate loyalty. When the bottom fell out of the demand, the Company laid off workers and if they could no longer pay the rent, then they were evicted. The union movement found increasing interest from Pullman workers. By the way, Pullman did retain employees and sell cars at a loss at times before laying off staff. But the layoffs came.

The very kind of workers that the Pullman Company wanted, these were those most likely to chaff at the control of their lives and fates in Pullman Village. They were safe, sane, sober family men who would aspire to home ownership, who would want an education for their children and taken an interest in it, who would want a social life for the housewives, who would want family entertainment, who would want and expect job security. But George Pullman would never relinquish control of anything he owned, not one iota.

The result was the Pullman Strike that went from bad to worse. While the workers offered negotiation, the Pullman Company quickly resorted to force, and was shocked to find resistance. It spiralled out of control amid much posturing. Debs called every calamity a victory. George Pullman affected wounded pride. President Grover Cleveland sent in 12,000 Federal troops, three for every striker. (President Cleveland currently ranks in my book as the worst incumbent.)

The overkill of the corporate and political oppression galvanised public opinion against the Pullman Company. Religious leaders, newspaper editorialists, and even Chicago businessmen blamed the Company, not the strikers. George Pullman found himself ostracised among the business elite and that made him more stubborn. It became a test of wills, one he lost.

In the long aftermath, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that the Pullman Company must divest itself of the town. The annual Labor Day holiday in the first week of September was one of the concessions to the union movement from this strike.

Stanley Buder.

Stanley Buder.

After a hiatus, the Pullman Company survived but was never the same again.

Nothing is said about race, but many members of the over-the-rail staff of Pullman were black. There is much else in the book about the business practices of Pullman which I found of interest. For that, read the book.

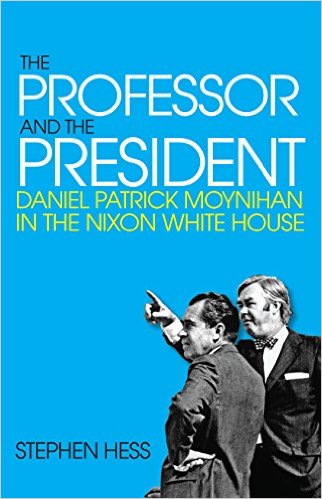

Stephen Hess, ‘The Professor and President’ (2015)

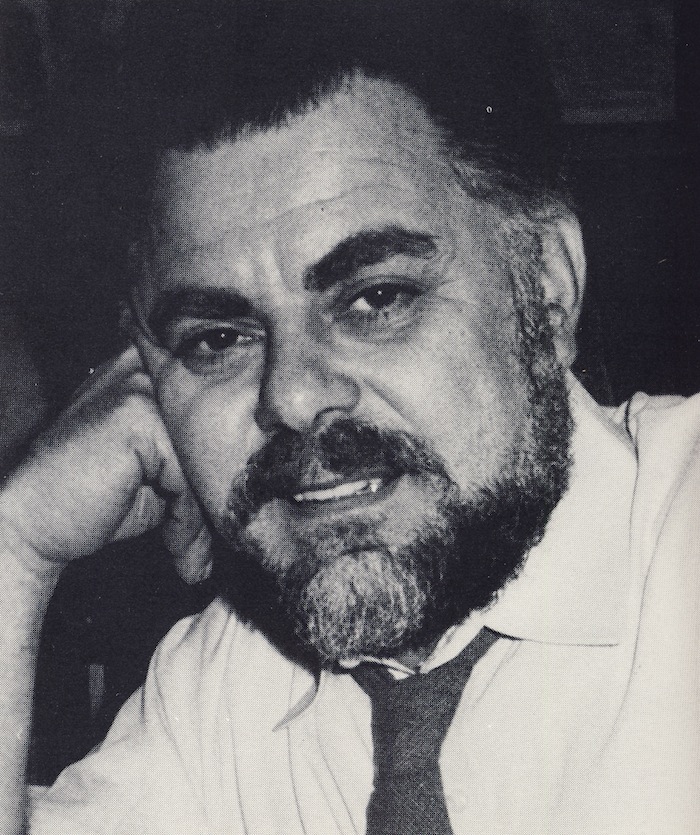

A memoir of sorts from the two years in 1969 and 1970 when Daniel P. Moynihan, with Hess as his deputy, served as President Richard Nixon’s chief advisor on domestic policy.

It was the odd couple: the president was a social conservative who courted to the right wing of his party to get the nomination and then moved further right to win the election joined with a high profile exponent of liberalism in American politics. Nixon ran to the right in 1968 first to secure the nomination from much more liberal Republicans like Charles Percy and that Hamlet of the Hudson Nelson Rockefeller. Then Nixon ran even further toward the right to undercut segregationist George Wallace’s independent campaign among those red of neck. Each time the message was simple and clear: law and order, cut welfare to zero, wind back the clock on affirmative action, stop integration by ending funding for its support, stack the Supreme Court with non-entities who would deny government intervention to support minorities…. That was rhetoric. It has a strangely contemporary ring to it, does it not?

In office the reality was this. Nixon wanted peace and quiet in the United States and he personally wanted peace and quiet in the White House. He was willing to buy domestic peace and quiet. Moreover, Democrats controlled both houses of Congress and seemed secure in continuing that. Nixon saw no reason to rile up Congress on domestic matters that he, Nixon, did not care about, nor to stir up the population by eliminating programs that had popular support. None of this could be done overtly for fear of alienating his electoral constituency which he would need again in four years. It was time for some legerdemain.

Enter Pat Moynihan. His credentials as a liberal in American politics were unassailable. He had worked for President Kennedy. He had advocated the cause of minorities. He supported all manner of social programs. His intellect was bright and he was a wordsmith, and he had other credentials, too, as a Professor at Harvard University. Robert F. Kennedy was dead, but Moynihan was his living spirit still flesh. Moynihan embodied from the bow tie on the Eastern Liberal Establishment that Nixon hated privately almost to distraction.

But it would placate Congress and confuse and perhaps divide his critics if he keep Moynihan close, and so Nixon appointed him as the chief domestic political advisor with cabinet rank. It was a masterstroke that won much breathing space for the new Nixon administration.

At the outset it seemed that Nixon’s administration would be dominated by two Ivy League professors, since his chief foreign policy advisor, appointed earlier, was Henry Kissinger, another Harvard professor, head of the National Security Council with cabinet rank. Remember that Kissinger had entered public affairs with Nelson Rockefeller, the most liberal of the Ripon Republicans (a phrase no longer used by the Grand Old Party). Are these two twin and each a deuce philosopher-king?

One of the interesting observation in the book under review is the comparison of the communities in the White House for domestic and foreign policy. While foreign policy is the preserve of the President, per the Constitution, and only two agencies figure in it, though they are the great and good Departments of State and Defense. In fact, with the appointment of Kissinger and the elevation of the position of Director of the National Security Council to cabinet rank, Nixon enlarged the foreign policy circle. It was still, however, a small circle. All the principals could sit around one small table, and a single strong personality could dominate the group, in this case Kissinger, even though he did not have the powerful Department of State and Defense at his back, he had the intellect and cunning to out manoeuvre them to influence Nixon. But that is another story.

In contrast the domestic policy community is vast and ill defined, but it starts with every other cabinet member, fifty state governors, and expands from there.

Moynihan saw an opportunity to dominate the domestic policy community with his own intellect. It would be a contest on two levels. The first was to get Nixon’s attention to domestic policy and the second was to displace his principle domestic policy rival, the economist Arthur Burns. The first step was simple and easy and had continuing implications. It comes down to real estate.

Thousands of people work in the White House and it has long since burst at the seams. Nineteenth Century broom closets have been converted to offices, hallways reduced in size to enlarge offices to shoe horn in more people, doubling and tripling up is the norm. The alternative was the Executive Office Building nearby. Moynihan opted to squeeze into a White House broom closet a few steps from the Oval Office, while Burns chose an opulent suite of rooms in the Executive Office Building. That was very nearly end of story. Game, set, and match to Moynihan. He was at hand instantly, and he made use of that.

In a way that says it all. The imperceptive Burns probably never quite realised it was a competition, and conveniently excluded himself. He further reduced his own influence by his ponderous class room manner. He could not participate in discussions ad lib. He could not debate submissions and never got to the point, if ever he had one, in less than forty-five minutes. If asked for comment in a meeting he would go away and write a lecture to deliver a week later. It was no contest. Nixon, in fact, began to interrupt Burns to ask for the conclusion, and then simply stopped inviting him to meetings. Moynihan excelled at debate and was always ready with an idea.

Getting Nixon’s attention was harder. The Cold War was very cold; the Vietnam War was very hot. The Middle East was on fire. Other trouble-spots vied for attention by more outrageous events.

But domestic policy could not be neglected. There were racial tensions and riots. Moreover, many Johnson programs were coming due for renewal and Moynihan was a genius at using these calendared deadlines to create some domestic policy for Nixon. He conceded some of the Great Society program to the dustbins, re-badged others, and merged many to serve up a diverse and responsive domestic policy. More importantly, he couched it all in terms Nixon could recognise and accept. That is, Moynihan played to the President, whose own background was one of hard times during the Depression. For two years the magic tape held.

Nixon came to like Moynihan who addressed him as an intelligent and well-meaning man, and did not act either the sycophant or supplicant. Sometimes Moynihan addressed complicated arguments to Nixon, in a rain of memoranda, on the assumption that Nixon would read and understand. These memoranda were often short, always witty, and usually tuned to the day’s headlines. Nixon liked being treated as an intellectual equal by this star from the Harvard firmament, just as the star liked being asked to advise on all manner of things, many beyond his remit.

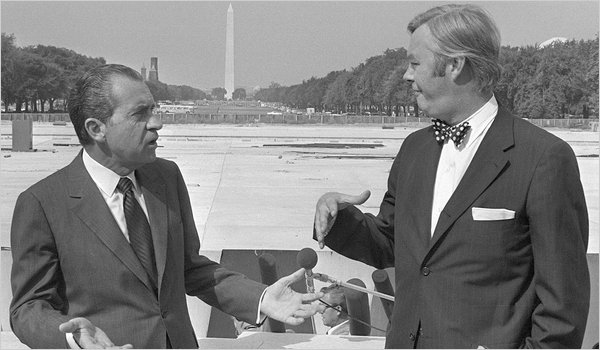

The odd couple.

The odd couple.

It did not last because when all is said and done, well, Nixon was Nixon. He was unable and unwilling to ply Congress on domestic policy. By that I mean, Nixon was not someone who would court the support of anyone, still less in a policy arena in which he had no interest. Part of his dedication to foreign policy was because it was essentially the President’s chess game. He played the lone hand. At that he excelled.

To promote any domestic policy requires a president to woo, court, explain, cajole, coax, trade favours, entertain, persuade, the chairs of sub-committees, the chairs of committees, the party elders, the lobbyists, the press, individual Senators, faction leaders formal and informal, state governors, certain Representatives, and so on and on and on. This kind of endless dance was what Lyndon Johnson did better than anyone before or since, seldom idle and never alone when he could press his case on someone.

Nixon thought this kind of politicking without end led to compromises and bad policy, or so he said, but the truth is deeper. He just could not do this person-to-person persuading even if it was scripted and controlled. We can all speculate on why. Here is my take. Because of his background of penury he was too proud to ask others for help. To do so would be admission of weakness, and the weak are reluctant to admit it. There is also in Nixon a personal shyness that is another result of his upbringing that kept him in the family. That is my pop psychologising. (Yes, I know LBJ’s background was even more penurious and he had no trouble in seeking help.)

After the first few months of his presidency Nixon sharply reduced the time he spent in cabinet meetings, and made himself less and less available for appointments with anyone. Bob Haldeman who kept Nixon’s appointment diary noted that the President said and said often ‘I want to be alone.’ Yes, I thought of Greta, too, as I am sure did Hess, but he passed it in silence.

Nixon had to be alone with those yellow legal pads to think. When Nixon was thus isolated, as he preferred, Moynihan was a few steps away and would be summoned to be a one-man sounding board, who would speak freely in the privacy of the tête-à-tête.

Like Senator William Fulbright, Moynihan had made a Faustian bargain. He joined Nixon’s band on the pledge of loyalty and that he would not speak of the Vietnam War which was the biggest and hottest ticket for the incoming president. Moynihan kept his part of the bargain.

It lasted for two years and then Moynihan returned to Harvard. He paid a price for his association with Nixon and gradually went on to a political career in the Senate, taking the seat once held by Robert Kennedy.

The price was a loss of status among his Harvard peers for his dalliance with Tricky Dick. He never quite re-entered the Harvard Square club. Indeed, his association with the Nixon White House also damned him to many anti-Vietnam War protestors. The one chance I had to hear Moynihan speak, at a political science conference, he was shouted down, quite comprehensively, by such protestors.

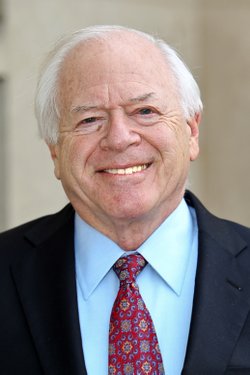

Stephen Hess has many other books, and I will certainly read more.

Stephen Hess.

Stephen Hess.

He is even handed, and lets the facts do most of the talking. He does, however, present most of this book in the present tense and I found that distracting, and I always find it annoying after I have been distracted.