Francis Bacon (1561-1626) has many claims to fame, but this book is mainly and obsessively concerned with one of his claims to infamy as a betrayer of Robert Devereux, Second Earl of Essex, a favourite of Queen Elizabeth who overreached himself. Essex was patron to Bacon’s client. It is a study of the formation and transmission of Bacon’s reputation with periodic rehabilitations and denunciations.

Insofar as the book is a study of Bacon’s reputation, there are comparisons to Niccolò Machiavelli. Like Machiavelli’s contemporary Thomas More, Bacon was both a scholar and a politician, as was Machiavelli. For all three of these men the ease with which erroneous assertions become fact by repetition is remarkable and once realised causes me to wonder what else in received option is equally erroneous.

To blacken Bacon’s name takes only a few words. To rebut and refute that assertion takes many pages to detail context, to infer intention, to shift testimony of eye-witnesses and so on. Believe me, Nieves Mathews is just the woman for the job of filling pages, though she complains more than once that she has too few pages to do the material justice. I took these asides to be references to the publisher’s insistence that the book end … sometime. She complains that Ignatius Donnelly’s book on Francis Bacon was too short to do justice to the subject. Too short at 900+ pages! See what I mean?

Essex is well known to anyone with even a slight knowledge of Queen Elizabeth. He was an attractive young man who captured the Queen’s interest and held it, despite some appalling behaviour. His indiscipline combined with hubris of considerable proportions such that he put himself forward for all manner of things, and he got some of them. He was promoted several levels above his competence. Thus was he sent to Ireland as the head of an army to quell the fractious Irish. For most of that campaign, at great expense to the public purse, he disported, drank Ireland dry, left no wench go unmolested, wrote piteous letters to the Queen lying about his noble efforts on her behalf, and knighted seventy (70) of his drinking buddies. That escapade alone, and it was not unique, gave his enemies ammunition for a lifetime.

Bacon counselled moderation to this wastrel with a patience that bespeaks the lack of alternatives. Bacon was Essex’s man and he did his best to help him. Of course, Essex knew no bounds and when his plot against the Queen foundered Bacon was safely clear of the fallout. Like many others in politics, Essex contended that his plot of seize the Queen was to protect her from others with sinister designs on her. Perhaps because even the dim Essex realised Bacon would not play, Essex made no effort to involve him in the plot. Or, more likely, Essex regarded Bacon as unimportant. None of the copious correspondence produced as evidence against Essex named Bacon as conspirator. Nonetheless he was guilty by association in the minds of many then and since.

The story is not as clear-cut as summarised above. There have since been apologists and historians who see in Essex a victim of other forces. In that light, Bacon figures as a false friend who either betrayed Essex by revealing the plot, did too little to stop Essex’s mad scheme, or did too little to reconcile the Queen him. For the Essex-apologists Bacon’s treason to Essex is proven by fact that Bacon survived the drama and Essex did not.

Bacon’s reputation as a savant and public servant was sound for two hundred years until Baron Macaulay (1800-1859), wrote a hundred page essay on him, while resident in Calcutta during his tenure on the Indian Supreme Court. That got my attention because this same Macauley made a valiant attempt at about the same time to rescue Machiavelli’s reputation.

Back-and-forth through these 592 pages Mathews refutes every word Macaulay wrote and some he thought of writing but did not and still others he might have written. It is as thorough as a very expensive legal brief and just about as interesting to read. She is not one to summarise evidence when it can be paraphrased in full over pages and pages.

Macaulay started an anti-Bacon trend which she details from sources I never heard of but then I did not know his reputation had ever been blackened. She quotes letters to editors from literary magazines in 1891 to prove the point. Did I say ‘obsessive’ above? I did. It is. The thoroughness is that a PhD dissertation but it is not that, as I discovered when I tried to find out more about the author. For that see below.

Every card has been played against Bacon, she says, including the speculation that he was homosexual. My, my another comparison to Machiavelli who was accused of this practice by some plotting his downfall.

She also has a chapter on Bacon’s reputation in France, Germany, and Italy. No stone is left unturned. Among these enlightened Continental people he has long been recognised as a savant without equal.

‘I know of no other Renaissance writer who is so regularly vilified,’ said Brian Vickers (qv., p. 406). Brian should get out more. Try Machiavelli.

I did love her description of a Penguin edition of Bacon’s ‘Essays’ as aimed at discouraging students from ever reading them with the many derogatory things said of the man and his work in the editor’s preface. There is a student’s guide to Plato that is similar. Its editor, an Oxbridge don of high repute, is so plainly bored with Plato that he ends up making him boring. Penguin editions are cheap and available, but they are not always the best.

Overall this book is combative, sometimes polemical, but the subject matter saves it. Bacon was an interesting man and so were his times. Though it remains a mystery to me why Yale University Press published it. There are many mysteries out there, Scully. Another is the gentle review in the ‘American Historical Review,’ which went so far as to praise the writing style. Sometimes one suspects that reviews have not read all the way through a book.

Bacon’s claims to our attention are many. Along with several others he has been granted title to the plays and poems to which William Shakespeare put his name. Others have credited him with writing most of the works attributed to Michel de Montaigne, and still others say he wrote ‘Don Quixote’ in his spare time. True. He held two major public offices in the turbulent world of the Tudor and then Stuart courts: Attorney-General and Chancellor of the Exchequer. In addition, he served in parliament for many years. He articulated the scientific method, or at least, empiricism as a foundation for science, including particularly experimentation. His personal private secretary for some time was Thomas Hobbes, that giant of political theory. His personal physician was William Harvey. He knew a lot of big brains. Moreover, Bacon’s 40-page book the ‘New Atlantis,’ gave rise to cult of the Rosicrucians. However, some readers will be disappointed to know that he has nothing to do with the food of the same name.

The Child Bride gave me this book for Christmas some years ago. I tried to read it then and found it hard going. Feeling guilty after leaving it to ripen on shelf, when my eye fell on it recently I took it up to try again. Hard going. It is a specialist monograph based one extensive research into the time and place written without concession to an avocational reader (me), and the prose is leaden. Still it did get me thinking about Francis Bacon.

The author’s full name is Nieves Hayat de Madariaga Archibald, Mrs. Mathews (1917–2003). This from the Wikipedia stub: ‘She was also deeply influenced by the works of Immanuel Velikovsky. In her earlier years, 1956, she wrote a crime novel, ‘She Died Without Light’. She was inspired to do the Bacon book by Chandra Mohan Jain (1931-1990), also known as Acharya Rajneesh from the 1960s onwards, as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh.’ Her guru told her to do it. If Velikovsky is unknown, my advice, is to leave it that way.

Category: Book Review

‘A Robert Penn Warren Reader’ (1988).

The volume offers a selection of this prolific writer’s oeuvre, poems, essays, plays, short stories, excerpts from his novels, forwards and prefaces he wrote for the books of others.

Warren (1905-1989) wrote one of the best novels ever, especially for political junkies, ‘All the King’s Men’ (1947); three or more times butchered by Hollywood, it remains evergreen despite the assaults by the Tinsel Town pigmies.

The opening of that novel strikes an hypnotic chord in which the rest of the story unfolds. Marvellous.

Most of the items in this collection were composed between 1940 and 1965. He was Poet Laureate at the Library of Congress in the 1970s and his greatest fame lies in that world, poetry, amply vindicated by the poems included in this volume, each a small study of nature or humanity.

Like many others of the South his greatest challenge was the obvious one of slavery past and racism present. As an undergraduate he defended segregation, as did his professors and peers at Vanderbilt University, including that other remarkable Southern poet, Allen Tate, but Warren grew out of it and quickly, unlike Tate. Warren’s short monograph ‘Segregation’ (1956), included between these covers in its entirety, offers his personal bildungsroman along with penetrating insights into the manifold evils segregation spawned. Though this account lacks the hellfire and brimstone of his comrade William Faulkner’s many denunciations of the racism, being more cerebral and measured, yet it strikes hard, sure, and deep. His reference to the remark attributed to a Southern plantation wife says it all, but so succinctly and so swiftly that I had to read it twice to get it. ‘Mr. Lincoln freed me of slavery and I thank him for it.’ (Either you get it or you don’t.)

Among the pleasures in this volume is a short but layered appreciation of the nineteen novels of William Faulkner. Faulkner’s many failures and weaknesses, on Warren’s telling, were essential to Faulkner’s astonishing successes and strengths. The man was whole and so is his work, and that is how we must take it.

The same themes run through his commissioned monograph ‘The Legacy of the Civil War’ (1961), included here. There is too much in it to summarise but to this reader the most striking passage is when Warren asks readers to imagine Robert E. Lee shaking hands and congratulating the strutting Southern governors of the 1950s and 1960s barring children from schools, encouraging baying crowds of Bible-grasping gorgons to shout abuse at girl scouts, licensing hissing mobs to burn churches, sanctioning lynch parties, ignoring rape and pillage for sport, and praising masked men hiding in the dark.

A close examination of pictures from the March on Washington in 1963 will show Warren there on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial come to give his own thanks.

He received three Pulitzer Prizes for his work, living most of his latter years in New England, no longer welcome in his homeland, and it shows in the poetry.

In a classroom at Yale University where he taught for years.

In a classroom at Yale University where he taught for years.

The wonders of nature and humanity remain many and varied, but the sense of loss and disconnection is but palpable.

A callow undergraduate, I heard him recite some of his poems and the memory has since remained bright. There are some short excerpts on You_Tube.

Miguel de Unamuno, ‘Abel Sanchez’ and other stories.

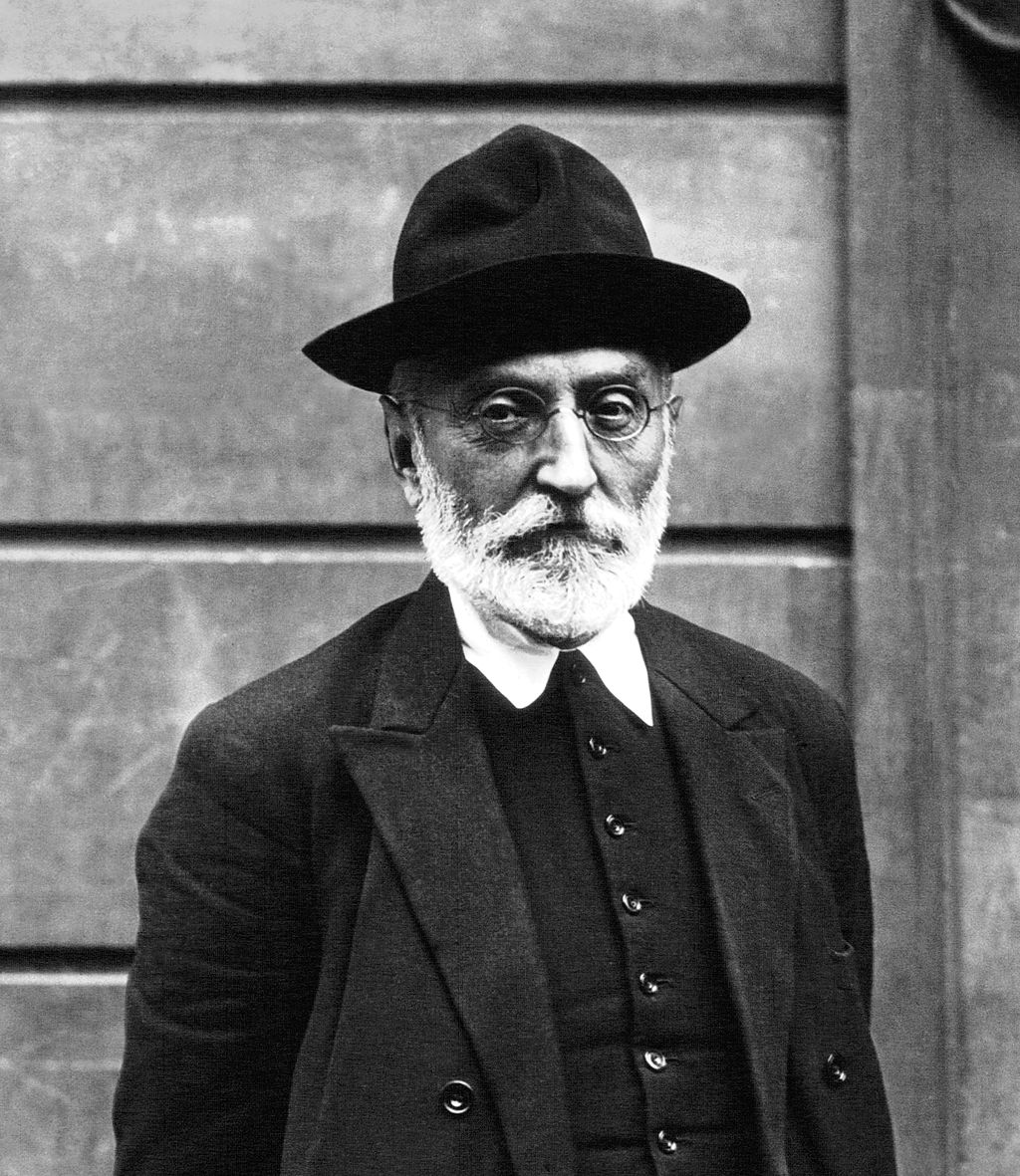

Listening to John Stuart Mill’s autobiography reminded me of a story by Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936), a pioneer in existentialist fiction and philosophy in Spain. That name by the way is Basque and though ‘Unamuno’ clearly means ‘one world’ it is not from any known language. In this as in other ways, he was one of a kind. He wrote fiction, poetry, drama, and essays.

Miguel Unamuno in 1925.

Miguel Unamuno in 1925.

When Mill talks about losing faith in unified and theoretical solutions to human problems, it echoes Unamuno’s story ‘Saint Emmanuel the Good, Martyr’ of the eponymous priest who loses his faith in God and yet continues to minister with continued dedication to ease the lives of his parishioners. It is a very moving story of self-sacrifice, told in a slow and subdued manner over sixty (60) pages. The scene in the confessional when he, the priest, confesses to the young penitent Angelica his loss of faith is remarkable. Readers will long remember Don Emmanuel and his daily struggle to act as though life has meaning.

The second story is ‘The Madness of Doctor Montarco’ which is social criticism, and daring for the time and place. Montarco is a fine physician and as a pastime he writes and publishes in newspapers and magazines ever more farfetched stories which we might label as fantasy or science fiction. His patients begin to doubt his ability and reliability because of these stories, despite the evident fact, attested to by other doctors, that he is treating them very, very well. The patients lose confidence in him and desert his practice, and as this happens the stories he writes become ever more bizarre and disturbing to readers, until he finally enters an asylum to live out his remaining days a confused and broken man. It is a story about the fate of those who do not conform to the narrow channels of the Catholic and conservative society of Spain which rejects this re-born Don Quixote. This is a twenty (20) pages story.

The title story is a short novel of 176 pages, ‘Abel Sanchez’ in which Unamuno tells anew the tale of Cain and Abel in contemporary Spain circa 1930. It is a marvellous study of the jealously, envy, and madness of Don Joaquín (Cain), another doctor, who hates his best friend Abel Sanchez for all his apparently easy success in life and love, and Joaquin plots his downfall. I read the first sixty (60) pages in a gulp. Abel is a painter whose work acquires much recognition and financial success and leads to his marriage to Joaquín’s cousin, Helena who had earlier refused Joaquin’s proposal. He, the man of science, who saves lives is shadowed by this frivolous artist and trumped by him at every turn. Yet such is Unamuno’s artistry that Joaquín is largely a sympathetic character, as are Abel and Helena. That is the tragedy, there are no villains here and yet there is destined to be a collision.

By the way all three of these works were put on the Index Librorium Prohibitorum, forbidden to Catholics.

The tattered copy I read was an undergraduate text from my college days for which I paid $1.25 in 1967. I have read and re-read it several times since.

The dictatorship of Primo de Rivera exiled Unamuno to the Canary Islands from when he escaped to live just across the border in France. HIs writings were considered incendiary, including the works of fiction above. He returned when the Popular Front government took office in 1936, though one can hardly describe him as a liberal, a socialist, a communist, or an anarchist. He was a staunch Catholic but one who could see the reality behind the curtain. In any event when the Civil War came he denounced it very publicly from the lectern in Salamanca where he was rector of the university with members of the junta sitting in the audience and on the stage while he spoke. It must have been electrifying to see this hunched and weary old man challenge the Goliaths in their gold braided uniforms and sidearms. He was nearly lynched on the spot.

Passing through an angry mob of Nationalists.

Passing through an angry mob of Nationalists.

He died a few weeks later. Federico Garcia Lorca was murdered even earlier that year, he being another genius of Spanish letters. There are now monuments to both of these writers, but none to the men who killed them.

‘A reformer of the world’

Reading Nicholas Capaldi’s biography put me in mind of John Stuart Mill’s ‘Autobiography’ and I found I had it on Audible already, so the rest was easy, well not quite. See below.

Although his voice was a clarion for social equality and personal responsibility, generations of students have since been taught to despise him as a progenitor of evil liberalism. Sounds odd I know but since the 1970s jaded intellectuals have made careers biting the hand – liberalism – that feds them, having insufficient imagination to do anything creative themselves. When these pygmies are long gone, John Stuart Mill’s books will still be read; that will be the judgement of history.

Mill started to write the ‘Autobiography’ when he a nervous breakdown early in life and then went back to it later. In addition, Harriet Taylor had a hand in editing it. Many PhDs have been earned trying to figure out when Mill wrote portions of it, and what Taylor took out or put in. The Audible version I listened spared me this detail.

The early chapters are a description of the childhood of this prodigy with an emphasis on his father’s method of educating him. It is exhausting to listen to the account, the more so knowing, as he must surely have himself known in retrospect, that most of it was meaningless. Prodigious, yes, but not lasting or meaningful. He may have read in Greek Plato’s ‘Apology’ at five years of age, but he did not understand it. So, too, with much else in this force-fed education, which was all work and no play everyday for years on end.

One unintended consequence of this gruelling education was that Mill was a Galaxy-class nerd. He grew up in a hothouse that he seldom left until he was a late teenager when he went out of the house to go to the East India Company where he worked for his father. He was in his father’s shadow for much of his life everyday, socially, intellectually, morally. It is painfully apparent to an auditor of the ‘Autobiography’ that Mill had no friends. He had peers; he had colleagues; he had associates; he had debaters and opponents. But he had no friends, which he as much as says more than once. Part of the reason for that is that he had no interests but the unforgiving logical analysis of important matters learned from and constantly reinforced by his father. This is not the person to sit next to at dinner. He could debate the great issues of the day but he could not make small talk, or show any interest in pictures of a seat-mate’s children. A cold fish, I would guess. Ready to beat you to death in argument and inept in passing the butter. That he never played any boyish games meant he had zero physical dexterity, hence the comment about the butter.

Chapter Five (5) is superb. In it Mill reflects on his many and varied experiences, and knocks off some bon mots as only he could. He paraphrases Thomas Hobbes’s remark that ‘When reason is against a man, he retaliates by being against reason’ which made me think of all those deniers (climate change, Catholic Church pedophilia, Holocaust, etc.). I listened to this while walking the dog, pushing pedals at the gym, or taking the train, so I could not take notes or mark-up the text.

HIs conclusion in this chapter is that political theory is best confined to a few principles which would allow inferences to be drawn in particular circumstances, rather than trying to lay down a set of single ideal institutions. Like Miguel Unamuno’s story about Don Emmanuel, Mill lost faith in a singularly unified theory and recognised the inescapable influence of context. (Unamuno’s story made an impression upon me, Don Emmanuel is a village priest who loses faith in god. Read it.) Under the influence of Alexis de Tocqueville, Mill wanted the deductions to be based on facts, hence I referred to inferences above.

John Stuart Mill, London, The Embankment

John Stuart Mill, London, The Embankment

Likewise, Mill concluded that perfect political institutions were of no value in themselves. The underlying social order was decisive. The most perfect political institutions would be hollow shells unless the society valued and embraced them for their purposes. To make a comparison, the church may be full, but do they really believe? Did they act like Christians everyday, or only for a couple of hours on Sunday?

Mill once fancied himself ‘a reformer of the world,’ but during his depression, he asked himself this question: If all the material and moral ideals he espoused were realised in the world, would he then be happy? No, he answered. He concluded that happiness if not an end in itself, but rather a by-product of purposeful activity. Both trip and arrival are important.

There are some odd things about the ‘Autobiography’ to be sure. Mill never mentions his mother though there are many, many references to his father who died when Mill was thirty (30). It would seem his father had those nine (9) children all by himself. James Mill was a formidable fellow but he was no hermaphrodite. While there are only a few early references to Mill’s work for the East India Company. Yet Mill specialists have some strange stories about his habits at work.

This review affords an opportunity to correct some errors I made in the review of Capaldi’s biography. It was not Bentham that introduced Mill to poetry. Several peers led him to poetry. I also said he was called a Mechanical Man, not quite, but rather a Manufactured Man by some who found the analytical engine of his mind artificial and inhuman.

I found this Audible reading to be unsympathetic. It sounded almost mechanical, phrases of equal length and inflection followed one another without regard to the content. Perhaps that is partly a fault of Mill’s writing style, which is replete with dependent, relative, and embedded clauses with asides and comparisons which makes it precise but it has no flow.

Not quite easy I said, because Audible kept dropping out, asking me to log in again, resetting the book mark, and so on. None of that is easy when using the iPhone while dog walking. No doubt I brought this on myself, somehow. But it was annoying, and a lesser man might have quit.

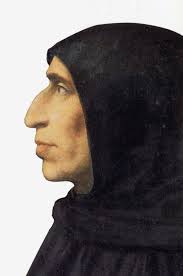

‘The Life of Girolamo Savonarola’ (1952) by Robert Ridolfi

Savonarola (1452-1498) was a critical figure in the history of the city of Firenze (Italia). Born to a comfortable family he learned Latin as preparation for a career in law or medicine. But a dream when he was twenty (20) convinced him to renounce the world and take orders in a Dominican monastery. His sleep then, as throughout his life, was troubled, perhaps by ulcers, speculates Ridolfi. In this troubled sleep he feared for his immortal soul because, well, he was a young man and his thoughts often turned to young women.

Giro never did anything by halves. He left home at night leaving a letter behind and entered the Church never to leave. Thereafter he had little contact with his parents or siblings. Then his apocalyptic thoughts turned from himself to all mankind.

Though well educated he had a thick accent from his region, Ferrara, north east of Bologna. This marked him as an outsider wherever he went. He was holier than thou and was sent from place to place by his Order (Dominican) trying to find a place where he fitted in, did something useful, and was content. He had few chances to preach but when he did the message was repentance. He was assigned to a monastery in Fiesole just outside Florence. This building is now part of the European Universities Institute where I spent a semester once upon a time.

With his Ferreranese accent, his gloomy message, and his blunt manners he did not fit into Florentine society at the birth of Renaissance where the emphasis fell on elaborate manners, rich clothing, refined tastes in religious art, sensual music, and optimism about the future at the time of Lorenzo il Magnifico (a conventional honorific that was descriptive in this case). After a brief residence, Giro was sent away on other duties, but he later returned. In the meanwhile he had an epiphany, being called by God to scourge the world of sin, he said. A big job for one humble monk but he shouldered it. He began to preach with a newfound confidence, speaking slowly and in simple phrases, though always in Latin, he denounced arbitrary taxes that deprived humble people of the means of honouring god by giving alms. He denounced those who lavished money on useless trinkets, i.e., fine clothes, paintings, sculptures, etc. in the city where Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo were hard at work, and Filippo Brunelleschi had made that great dome.

Statue of Savonarola in full flight, Ferrara.

Statue of Savonarola in full flight, Ferrara.

His populist message found a constituency and his sermons attracted ever more auditors. Lorenzo tried to get him re-assigned elsewhere but the letter was lost in the Italian postal service where millions have followed them. (I got my letter of appointment to EUI about ten months after I returned from my tenure there. Thank goodness for faxes in those days). Larry then tried hiring some competition, and brought in some other, more showy, and acceptable preachers to no avail. He also tried to coax Giro into a more reasonable approach by asking a few local intellectuals to befriend him, which they did and both were won over by Giro’s sincerity and intellect. Hmm. He finally tried money but Giro gave it to charity. Then, considering it all small potatoes anyway, Lorenzo ceded the field.

In Milan Il Moro had invited the French King Charles VIII to support his rule, and Charles found Italy congenial. There was no match for the French army and King Charles, like some many other later tourists, found the shopping excellent. His army would appear, and whole towns and cities would surrender everything to him, gold altar pieces, oil paintings, rich silks, musical instruments, tapestries, fur coats, chests of gold, and a good number of women. He shipped home tons of boodle to stock up the Louvre.

Spain had a matrimonial alliance with Naples and soon enough these two incipient nation-states fought out their war in Italy over the next generation. The micro Italian city-states made shifting alliances with each other and France or Spain as seemed opportune. Venice watched with one hand on the sword, while the Pope in Rome schemed and plotted in hyperdrive. Cesare Borgia supported by his father, the Pope, seized his opportunity to create a kingdom in Romagna. Think of Afghanistan today, that is the picture.

When Charles appeared near Florence, Piero de Medici who had succeeded Lorenzo set a record in the speed of his surrender thus forever sacrificing the support of Florentines who, being traders, expected him at least to bargain. Charles was not at all sure that Piero could deliver the goods, and bided his time. Then the Signoria sent a delegation of four to plead with the king to spare the city. Because of his perfect Christianity, Savonarola was one of the four. He found common ground with Charles by appealing to his Christianity and Charles spared the city. Giro was hailed as a hero. It is more complicated than that but it seemed to everyone that Giro had saved the day.

Giro had also had visions and predicted the future a few times, and enough happened to make the predictions credible. His direct line to God seemed very real. No wonder then that on occasion his sermons would attract 15,000 people. He was a celebrity by word of mouth. Crowds would gather to watch him walk between buildings, hoping that by proximity some of his divine grace would come to them.

During a calm period, the elders of Florence asked his advice (remember that direct line to the divine) on government. He suggested a process of generating and evaluating alternatives that results in three constituent bodies. What is impressive is that he suggested a process and did not simply say do this or that.

He also counselled moderation and clemency when hot heads wanted to exact vengeance on the followers of the Medici. His many enemies, including Medici loyalists, tried to trick him into making more prophecies but he proved astute in not biting. His oracular statements were few, making them all the more mysterious and remarkable. His fame spread throughout Italy. A Venetian ambassador was instructed particularly to observe and report on his activities.

Savonarola seems to have established some kind of relation to King Charles VIII of France during the latter’s several Italian campaigns, which Giro used to protect Florence. This elevated his status still more, but not with the Mediceans (though King Charles was reserving his options by tolerating the current Medici pretender in his entourage).

Factions in Florence rejected Savonarola’s castigations and threats of damnation and petitioned Pope Alexander VI (Borgia) to reassign, recall, criticise, and finally excommunicate him. The Pope went through the motions at first but did not follow through, until…. King Charles threatened Rome again, then the Pope tried to coerce Florence into joining the Venetian League against France and if it did, then he would tolerate Savonarola. If it did not, he would excommunicate him. This see-sawed for a while and further divided opinion Florence.

The executive of the Florentine government was elected every two months, and it oscillated both as to the emphasis placed on Savonarola and its support for him. In June the executive petitioned the Pope to recall Giro, and two months later another, new executive proposed his sainthood. Back and forth it went.

Meanwhile, Savonarola – becoming more extreme and apocalyptic – challenged believers to sacrifice their most precious belongings at Lent, not just forgo their use (say by draping statues or turning paintings to the wall which had sufficed previously). This happened in two successive Lents. The second time the pyre of goods (silk clothes, paintings, statuary, musical instruments, sheet music, books, manuscripts, etc) was so impressive than the Venetian ambassador offered 20,000 gold ducats for it, but Savonarola refused. That is an enormous sum. He must have been biding for the city of Venice because no individual had that many gold ducats. Earlier Giro might have taken the dosh to succour the poor, widows, orphans, cripples, the sick, but he had become more and more obsessed with symbols in the mystified world he inhabited.

His sermons also become more hellfire and brimstone, and he became much more agitated, voluble, and loud when he preached and began to pound the banister on the pulpit in castigating his congregation. In the streets there were clashes between his supporters and opponents resulting in injury and death. When King Charles VIII lost a couple of battles, Giro’s big brother friend no longer intimidated his local opponents.

The Pope’s efforts to discipline Giro got nowhere, but he wanted Florence, perhaps the richest city in Italy at the time, on his side and against the French. The last card was to threaten to excommunicate all of Florence. While many Florentines individually might have agreed with Giro that the Pope, being irredeemably corrupt, had no divine mandate to do this and laughed it off personally, it also meant an interdict on Florence so that no Christian would trade and do business with it. That is, it threatened the livelihood of the city and the fortunes of those who thrived on trade and business, which was most of them. That was serious!

Savonarola was also increasing erratic, even rejecting as evil sinners those who tried to help or protect him.

The Pope finally took more enegetic action, but the Signoria beat him to it. Savonarola was arrested and tried as a heretic, tortured repeatedly over several weeks, until brought to a point where he would confess anything, which he did. He was then hanged and burned in a public spectacle in the Piazza della Signora, where we many tourists have admired the replica of Michelangelo’s David. In all likelihood Niccolò Machiavelli, about 28 at the time, saw this. He has a few words to say about unarmed prophets later in ‘Il Principe.’

Giro published a lot of his sermons, and his acolytes acted as amanuenses at times and wrote his words down. To true believers he was a saint in all but name, and they spread his fame. Visitors to Florence looked at the art work and at Giro. He was also a prodigious letter writer and many remain.

Martin Luther was at it up north during this time, and he is the obvious comparison. Giro was less interested in denouncing the corruption of the Papacy than in saving souls by abnegation. He was also less egotistical than Luther, at least as portrayed in Erik Erikson’s biography ‘Young Man Luther’ (1958).

There is no doubt that Ridolfi’s sentiments lies with Savonarola. He smooths over some of Giro’s behaviour which I have read about in other studies of the time and place, e.g., he minimizes the bonfires of the vanities at Lent. Giro really whipped believers up to do this, and he encouraged them to break into public buildings and private houses and steal valuables to be burned, and no matter how much was burned it was no enough.

These days Giro is known to many tweeners as a character in Assassin’s Creed. To find out more about that, ask any 12-year old boy.

This English translation is minus the footnotes, though the text makes many references to sources and archives, these cannot be traced with this edition.

Michel Basilières. ‘A Free Man’ (2015)

In which Skid tells the story of his life, or a part thereof, to our nameless narrator who is trying to finish his second, long over due, novel, i.e., Basilières’s alter ego. Though a work of fiction it has some of the layout of nonfiction. There is a preface, and the text has footnotes that supplement the dialogue. The setting is contemporary Toronto.

Skid’s efforts are hindered by a Lem, a shape-shifting monkey from three hundred (300) years in the future. Yep! Lem tries to convince Skid that he is needed in the future. To do that Lem pops up at very inopportune times. Lem does that, pops up.

In the Preface our deuce Basilières makes it clear that he has laboured under expectations for a second novel since his marvellous first one (‘Black Bird’ in 2004), and that he had given up but would pass along this story from his friend Skid. Skid works in a bookstore and lusts after the female employees and customers, but being a terminally inept nerd he gets no further.

It sounds rather like Basilières himself, who works in a Toronto bookstore….

When a writer, or anyone else for that matter, speaks of the expectations – demands – of customers I am reminded of that Stephen King story ‘Misery’ about the writer trapped by a fan and chained to typewriter to produce more stories, and getting whacked by a baseball bat if the stories are not up to standard! Whack!

Michel Basilières

Michel Basilières

Some authors are one book authors, I have heard, and perhaps that applies here. Sympathise as I do for the angry and demanding god Expectations, the novel bears no relation to the exhilarating Black Bird. I am turning the pages through it in honour of that first novel. Let’s hope, however, that getting A Free Man out might stimulate Basilières to stick to the keyboard, and try again.

Jules Romains, ‘Men of Goodwill,’ volume 1: ‘The Sixth of October’ and ‘Quinette’s Crime.’

Jules Romains, ‘Men of Goodwill’ is the longest novel ever, running to twenty-seven (27) titles. Yes, 27! They have all but disappeared. Few libraries have the whole set, and finding a set to purchase was a long chase for me. They appeared in an English translation in the 1930s. Each volume contains two novels, apart from the last.

In this, volume 1, there are two novels: ‘The Sixth of October’ and ‘Quinette’s Crime.’

Romains’s description at the start of Paris awakening, stirring, moving on a working day is wonderful. He was a believer in some kind of collective consciousness in crowds and he sees this in patterns, recurrences, and actions and reactions on streets, in the Metro, on buses, in employees clocking in, bicycle riders at a traffic light, trucks backing into loading docks at les Grand Magazins.

Monsieur Quinette spontaneously hides a murderer and involves himself in the crime for no other reason than boredom, and because he is, he thinks, so much smarter than anyone else. He misleads the police, extracts the dosh, but finds Leheuday, the murderer, a thug and a loose cannon. He decides to off Leheuday, nick the dosh, and perhaps take Leheuday’s rather dim girlfriend, while leading the police on a merry dance. Deciding is slow work and his last scenes with Leheuday are interminable. But in the end, bang, bang, and he is dead.

It takes Quinette both volumes to shoot Leheudey who murdered an old women in the opening pages. In another of the several threads started in these opening volumes, the students Jallez and Jerphanion meet and they continue through the remaining volumes I think.

Jalllez and Jerphanion become friends, and the Minister of State Gurau discovers a plot against him. He is another who thinks he is smarter than those around him.

The street scenes are well described. The interior monologues of Quinette and Gurau are well done but they go on too long.

Jules Romains, who broadcast for De Gaulle from New York.

Jules Romains, who broadcast for De Gaulle from New York.

The whole 27 volumes together comprise an encyclopaedia of Parisienne life — the high and the low. It reads rather like an encyclopdia, earnest, accurate, detailed, and bloodless. Still the characters are differentiated in manner and speech as part of the ethnography of types and the descriptions of Paris are cinemagraphic.

Alan Furst, ‘Red Gold’ (1999)

An espionage thriller from a master story teller who conjures an atmosphere of melancholy from a few lines. Most of the story takes place in grey drizzle with characters who get by on 1500 calories a day, wearing paper thin coats in the unheated rooms of Occupied France in early 1942. They are Jews, bystanders, communists, socialists, citizens, refuges, unionists, journalists who get caught up in each others’ schemes, some petty, some heroic.

The fear, the deprivations bring out the best and worst in people. Pretty Victorine in the travel agency sucks the Jews dry and then turns them in the Gestapo. A gendarme leaves the back door open while he goes to sharpen his pencil and the suspected resistant walks out.

The communists of FTP trust no one, certainly not each other. Students do half-baked, stupid things and get killed. These martyrs inspire others to do more stupid things, and so it goes. German reprisals grow in scale and scope. Life is the one, the only thing that is cheap and readily available.

Grim.

The prose is laconic and spare. In this oppressed world no one has the time for long winded perorations, or for second thoughts. There is no food and hardly any clothing to describe. It meets the Elmore Leonard test. If it is there, then it is important. What is not there is unimportant.

I have read a few of his titles before, but I do find them so melancholic and so grim that there is little pleasure In reading them. It is clear that nothing good is going to happen. And nothing good does.

‘Why Homer matters’ (2014) by Adam Nicholson.

The answer to the title question is in the Iliad:

‘The gods did this and spun the destruction of people

For the sake of the singing of men hereafter.’

Read on for an explanation.

I saw this title on an Amazon recommendation and bought it. My reaction is mixed. I learned something from it, to be sure, and I was reminded of other matters I had forgotten and that is all too the good. I will review some of that before turning to the vinegar in the mix.

The chapters on dating Homer and the Iliad reviewed the debates and evidence I had heard before as an undergraduate but also added a lot to it. Of course there are two issues in dating, one is the composition and the other is the event described in the Iliad. What was new to me here was both ancient and modern. The ancient part were excerpts from other ancient sources who commented on these two dates. The modern was the archeological finds that had not been ratified when I read the Iliad in college, one of which puts Homer himself a thousand years earlier than the received opinion of the 1960s! That reopens the question of the date of war he reported. Was it contemporary or many hundreds of years earlier still?

Then there is the recurrent question of Homer himself. Was he one person at a point in time, or was he several, each commenting on that big Asian land war, or several over time. Or was he the personification of a tradition of epic tales about a single war (or several wars, or a fictional war) in the way a Pop Music could be personified from fragmentary evidence so that a future archeologist might ask where Mr. Pop Music was born, how he managed to be so prolific….

The questions of dating and identity explain the differences between the Iliad with its rigourous hexameters and the varied measures in the Oyssesy, the obvious errors, the gaps, and the repetitions. One sample suffices, in the Iliad a named warrior is killed, his death detailed. Then a few score lines later he is back in battle! Homer nods, was the tag line.

The author does answer the title question although I am not sure he realises it when he quotes the lines above from the Iliad:

‘The gods did this and spun the destruction of people

For the sake of the singing of men hereafter.’

To explain, the gods led the men into this war to create events worthy of an epic poem of the magnitude and grandeur of the Iliad. Wars there were many, cattle raids, clan vendettas, boundary disputes over grazing land, pirate raids to rape and pillage in a day or two, involving this tribe, that village, a Kingdom here or there. But the scope of the Iliad adds all of those up and doubles it. Greeks from Ithaca on the Adriatic Sea to the Peloponnese, to Euboea in the Aegean Sea come together in a massive expedition. Jason had one ship and became legend. Here were a hundred ships to make an epic. None of these men would have been remembered but for the war, well, not quite, but for the poet who afterwards made the war and them memorable.

Art is life and the purpose of life is art. That is what we learn from Homer. Without art to capture, articulate, crystalize, preserve, and communicate life we are sheep in the field who leave nothing behind but dung and bones. When the flesh is gone, the poetry remains. That is Homer’s deepest meaning.

It is part of the genius of the Iliad is that it incorporates dissent, when the most enduringly famous warrior, the man at the centre of the Iliad, Achilles says he regrets it all. Famed as a warrior, slayer of men, many men, raper of women, many women, this same Achilles loved Briseis, loved Patroclus even more, weeps in the arms of Priam. This man of men is also a lover and loser. Fated, he knows. A preternatural warrior and an immature human being.

There were some omissions from the book, the foremost is some greater explanation of the origins of the texts we have. Does the Penguin Iliad trace back to…a complete Greek text on Egyptian papyrus? Is it the same original text that underlay Mathew Arnold’s Iliad two hundred years ago? When and how did Homer come to medieval Europe? Was he a travelling companion of Plato and Aristotle when Lorenzo Medici commissioned Latin translation from Greek masterworks then known in Europe only by references in extent Roman works. Plato and Aristotle we know did not exist in complete Greek texts but rather in Arabic translations that had survived and then a thousand years later were back translated into New Testament Greek. Without a doubt there were errors in translation. What was Homer’s path?

There is too much ME in the book. No doubt this personal element is an asset to some readers but not to this one. Knowing that the author thought of a passage from the Iliad when climbing the steps at…adds nothing and takes attention from the subject. There is a lot of this. Some has a thin justification in that he went to some of the places in Homer’s books, but even so, who cares these millennia later. He is no Homer. Moreover, he did not go to the obvious place, Troy and makes no comment on it. By the way, reopening the dates as mentioned above might mean Heinrich Schliemann was right about which layer at the site was the Homeric one!

I also found the comparisons to other Bronze Age people a long bow, and likewise the comparison of the Greeks at Troy to twentieth Century gang behaviour tenuous and tendentious. It filled the pages which I went over lightly, very without learning anything.

Adam Nicolson

Adam Nicolson

Many of the Bronze Age comparisons do not apply to the cosmopolitan, urban, artistically rich Trojans, and Nicholoson says that and then ignores it at other times. He generalises about Homer as though the Trojans were not there. Yet one of the beauties of the Iliad is that the poet does not take sides. Priam is majestic; Hector is noble; Andromache is stoic. These are the losers, the Asians. In contrast Agammenon is grasping; Achilles petulant; and Odyseuss is lazy. These are the winning Greeks, and no PhD has ever disputed that Homer was Greek and on the Greek side in some sense.

Stylistic irritations include direct address ‘you’ which I find distracting, a faux familiarity, and informal where the rigour of formality is the best support for exposition. There also seem to be some liberties taken or are they simple prejudices as when he gratuitously refers to ‘the sterilities of Oakland California’ on p. 74. There a few of these, shall we say, Bill Brysonisms: snide and superfluous remarks.

There are extensive notes but I rather think they were selected for fit not after analysis. There follows a long bibliography. I thank the author for both since I suppose it took a fight with the publisher to include these extras. That said, I judge them to be window dressing, not substance.

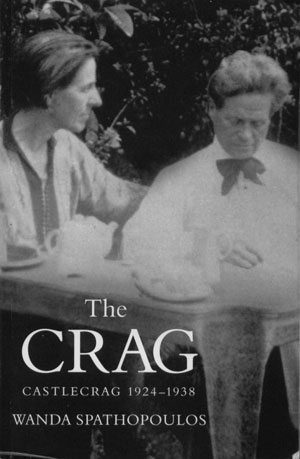

‘The Crag’ by Wendy Spathopoulos (2007).

The ‘Crag’ is Castlecrag on Middle Harbour, Sydney, a jewel hidden in plain sight on a peninsula, there are no through roads and so no passing traffic. Thus it is not known to many locals, despite its rich, even unique, history.

It has two distinctions. First, it is one of the last places in metropolitan Sydney that Aboriginals lived in their traditional way into the 1920s. There is photograph evidence of that in the Mitchell Library archives on Macquarie Street. Second, it was home to Walter Burly Griffin and Marion Mahoney Griffin, who created Canberra, the national capital, for more than a decade. This latter is the focus of the book under review.

The location, planning, and building of Canberra was a very large and lucrative political football, which was kicked and pulled in all directions. The main point relevant here is that there was an international design competition to plan Canberra, and the entry chosen by the selection committee had been submitted by Walter Burley Griffin of Chicago who worked with Frank Lloyd Wright, as did Griffin’s wife Marion. Walter and Marion migrated to Australia to contribute to the building of Canberra, setting up headquarters in Melbourne in Chinatown.

In short order a kick of the political football tossed Walter and Marion off the project, though the overall conception remained theirs, as did the eponymous lake when it was finally built (does one built a lake?) in 1961, fifty years later.

They had established an architectural practice in Melbourne and occasionally visited Sydney to meet clients. At some point they saw the wilds of Castlecrag and decided to move there. They set up a business to develop the Crag in accordance with their own planning and architectural principles, designing and building houses, parks, an amphitheatre, an incinerator, and a hospital.

In 1926 when Canberra was declared open for business in a grand ceremony, the Griffins were not invited. That will sound familiar to many who have toiled in large organisations with neither corporate memory nor simple courtesy but replete with strategic plans and a branding campaign…..

Wendy Spathopoulos summarizes the story above, but concentrates on the Crag years, which she witnessed as a child. She writes very well, strikes a balanced tone, and offers the results of library research, archival burrowing, interviews, and personal recollections. It is a mixture, to be sure, but she pulls it together well. Stories of colourful characters, and none were more colourful than Marion Mahoney, are mixed with the dreary struggle to get planning approval to build a house with the kitchen at the front near the street, and not at the back. Yes, Ripley, the Willoughby Council fought this to the end. Kitchens have always gone in that back and in the back they should remain. However, there was no legal grounds for this imperative and in the end, the Griffins prevailed.

By the way, they put the kitchen at the front so that deliveries from the street could be done easily; think of those times you have carried groceries through the house to the kitchen, and the point is made. In addition, putting the kitchen at the front meant the wife, inevitably at the time, had ready access to the street for child minding, for seeing neighbours, for reducing the social isolation of the wife at home.

The Griffins’ principles of design emphasised integration into the natural environment, per Lloyd Wight, and maximum functionality of space, including the roofs, which were flat for use in drying clothes, and as a patio. This also threw the Willoughby Council into hysterics, to judge by the minutes of meetings quoted in this book. Flat roofs were … unheard of, safety risks, a health risk, the work of Satan. But again there was no legal basis for the reaction and with persistence it yielded, but it shows that nearly every step was uphill.

It was all uphill in another sense, too, because Castlecrag is a ridge line with steep slopes on both sides down to Middle Harbour, and that pushed up building costs, though it kept down land prices. But by following the contour of the land, the Griffins tried to keep the cost of road building down, but once again Willoughby Council objected. Roads had to be straight, even if nature was not. Take it as read that Willoughby Council objected at each and every step to each and every thing.

The houses were small so as to be affordable, two bedrooms, with small rooms to economise on heating and lighting costs, with many large widows and serving ports to ease the work of the wife in the kitchen and walk through fireplaces that could heat two rooms. Yes, the Council objected to most of these design elements as well.

Marion Mahoney was larger than life and a dedicated amateur thespian. Hence the amphitheatre for the neighbourhood productions she orchestrated. She involved the local children in preparing the sets, props, costumes, and performing in some of the works where suitable. She and Walter knew many artists from Melbourne, some from Chicago and met more in Sydney. The players were amateurs but the productions were not amateurish. Marion designed and built the sets, as well as the costumes and props. The plays she produced included:

A Midsummer night’s dream – Shakespeare

Iphigenia in Tauris – Euripides

Prometheus bound – Aeschylus

The Green snake – Goethe

Oedipus Coloneus – Sophocles

In keeping with their commitment to the integrity of the environment, the Griffins spent a lot of time on storm water re-use — yup, another bone of contention, sanitation, and sewage. He designed his own sewer pipes because he found the Council standard inadequate. Guess what?

Spathopoulos describes both the Griffins as energetic, optimistic, and vital. The resistance of the Willoughby Council presented an opportunity to educate its members in design principles, building techniques, the value of social interaction, the integrity of nature, and so on. Thick skinned indeed these two paragons. However, banks were altogether harder since they did not hold public hearings. Banks? Yes, the banks were unwilling to lend money to buy such oddities as the houses the Griffins designed and built.

Walter also devised his own construction techniques and manufactured the building blocks to do it. Once again resistance was futile, if exhausting. He did not only design and plan, he also built and often pitched in on the manual labor. Marion was a keen gardner throughout the area, always native plants. Super-Greens avant le mot, they never uprooted a tree to build a house but planned the houses around the existing trees. Guess how the Council reacted to that.

Walter and Marion were keen connoisseurs of the many varieties of eucalyptus trees, and would have loved the novel ‘Eucalyptus’ (1999) by Murray Bail, I know I did; it is reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Walter taught the local children to identify the varieties of the gum tree with their Latin names.

While artists, some university people, a doctor or two bought Griffins houses in Castlecrag, they were few, and then the Great Depression came. King O’Malley, that giant of Canberra politics, remained a lifelong supporter and friend, bought a house as an investment. So did two Chinese the Griffins had gotten to know in Melbourne. Miles Franklin, the writer, was a frequent visitor but could not generate the finance to buy, and no bank would lend to a woman in those days. (Indeed about every 15 years there is a review into banking in Australia that discovers it is still true that banks are very reluctant to lend to women.)

Despite some trials, the Griffins prospered in Castlecrag, ever active and creative. They were active in the Theosophical Society and later the Anthroposophical Society, both forms of occult spiritualism which were in vogue at the time. There were one or two trips back to the States. He went to India on a commission and found much work there, and Marion joined him for a time. He died there and she returned to Castlecrag for a while.

Utopian theory and practice led me to planned cities, and I tried for years to interest a student in a thesis on that subject. Brasilia, New Delhi, Washington, Canberra, they offer plenty of choice. Hence I have read about Canberra and Griffins and saw in them a dotted line back to William Morris and one thread in utopia.

I put a visit to Castlecrag on the To Do list, and one day its number came up. There is a guided tour offered by the local residents association, on which I commented in an earlier post, and off we went. At that time I came across this title, but found it was unavailable and not in the University library. I put it on my Amazon Wish List and one day I noticed it was available and acquired it. It runs to 400 pages and has many photographs included. Too bad it is not more widely and easily available.

The book is unpretentious, straightforward, and lets story speak for itself, but I found the author’s decision to intersperse chapters about a visit to Greece distracting without adding to story of Castlecrag.

Your tax dollars work, published with an Arts Council grant.