Recommended.

The versatile novelist Ron Hansen strikes again. One change of pace after another from his ‘Mariette in Ectasy’ (1992) to ‘Isn’t it Romantic’ (2004), the first a study religious devotion in a turn of the century convent and the second a contemporary screwball comedy and this, an examination of the BEAST seen through the eyes of one of his very few relatives, a niece, the daughter of his half-sister.

It concentrates on the period between late 1919 and early 1930 and is based on biographical details spun by the novelist’s creative imagination into a tale of obsession, confusion, and demonic egotism. Hitler is almost human on occasion, but often playing a role to elicit the response he wanted from individuals at this early stage of his career: Pandering to some, bullying others, reasoning with a few, briefly avuncular.

I have never read anything about or by this the most famous man of the twentieth century, Adolph Hitler, so it was all new to me. The messianic self-confidence from the early 1920s that he WAS Germany (‘Du bist Deutschland,’ as Rudolph Hess always said), punctuated by lapses into exhaustion and doubt (human weakness) followed by a resurgence of manical energy charged with certainty.

The fulcrum of the novel is the niece Angela ‘Geli’ Raubal’s seduction by his aura, the prestige, and material wealth he increasing commanded with his periodic moods of sexual attraction to her and then revulsion from her. She became a canary in a gilded cage. Spoiled and then abused by turns, and at crucial moments lacking the will to break away when that might still have been possible.

Geli

This tension opens a window on Hitler, the man, through these crucial years. Hitler had at the start an iron self-control in public, and volcanic temper tantrums in private, but as his successes piled up, the line between public and private decayed for he discovered that he could get away with anything in public and still be hailed a genius. The temper tantrums were unleashed in his tirades.

Hansen gives us Rudolph Hess, Jospeh Göbbles, Hermann Göring, and others, all mesmerised by Hitler’s charismatic personality. ‘Charisma’ is a tried and trite word these days, and I try never to use it, yet there is no doubt it applied here. Hess and the others simply melt in Hitler’s presence, losing their wills and personalities.

The same applies to the thousands in the audiences of his harangues, though at a greater distance, they too are also compelled, lifted out of themselves by his exhortations. Hansen shows all of this, disgusting as it is, to be genuine, authentic. There is no cynical or instrumental calculation to explain their adherence, obedience, and the ensuing terrible deeds.

Long before he became Chancellor this man Hitler had a power over people that was tangible though invisible. There is the mystery at the core that continues to fascinate. After the explanations of time and circumstances are exhausted there is still that element left that defies conventional, rational explanation.

Yes, there were aristocrats, financiers, and industrial barons who thought they could manipulate this rabble rouser to combat the menace of communism, and then discard him, but they, too, as they drew nearer to him soon enough submitted to his will. Scenes in which Hitler seems almost deliberately to turn on his magnetic gaze — think Superman engaging his X-Ray vision — and bring to heel a millionaire, a full general, an heiress, a professor, a titan of industry, each his intellectual, organisational, or social superior yet all bowing down to this corporal without an education, with a grating Austrian accent, with a crude manner, spouting vitriol is …. astounding. There can be no other explanation but that word ‘charisma.’ The novel is a case study of that C Factor. (‘Charisma,’ for those who have not been paying attention.)

In David Fraser’s ‘Knight’s Cross: the Life of Erwin Rommel’ (1994, p. 433) there is an occasion when the war in July 1943 is going badly and Rommel, who had doubts about its conduct which as a good soldier he stifled, is scheduled to go to Berlin. This trip he welcomes because, he said, he would warm himself by the Füher’s radiance and gain re-newed confidence. It is a wistful, school-boy-with-a-crush kind of remark made by a decent, mature man who knew better and yet even he could not help himself. Rommel, like so many others, near or far, was hopelessly and helplessly in love with one Adolph Hitler.

There are many memorable scenes and events. Perhaps the best, for this reader, is the description of one of Hitler’s early speeches in an beer hall with an unruly crowd. Hitler is tight as a spring beforehand, nervous, angry, best avoided. He takes ten pages to the rostrum microphone in the hall, while the noisy crowd continues to drink beer and talk. ( We later learn that on each page is a bullet point in 10-15 words or so as a cue.) He begins…(after a few minutes the beer drinkers grow silent). The tirade mounts… (the beer drinkers lean forward to hang on every word). He continues … (the beer drinkers shout approval and applaud and he waves his hand and they fall silent like puppets on a string, this long before anyone even knew his name). HIs sermon becomes ever more explicit about what the problem is, what is to be done about it, concluding that Hitler alone sees the problem clearly and is willing to act on it with the merciless violence necessary to destroy the evils within Germany.

One crowd awaiting its master’s voice

He rants for more than two hours. The reaction is spontaneous and tumultuous. The beer drinkers rush to sign up for the Nazi Party. This is early in his career, there is nothing coerced about the response as would be the case later. He has jolted a nerve shared by members of this crowd – the western nations are eating Germany and Germans alive through their despicable agents the Jews, Jews and Communist are one and the same, wicked oriental cannibals, and the crowd’s response is galvanic. BANG! The poor, the uneducated, the impoverished veterans, dispossessed craftsmen, angry layabouts, the day labourers, the unemployed, the ignorant, these are the meek and they are being disinherited of their earth. For these, his is the voice. Hear it! Heed it! Obey it! (Christopher Isherwood says in this ‘Berlin Stories’ [1945] he went to a Nazi rally in 1938 and heard Hitler speak. Amid the shouting and frenzy he heard a familiar voice and turned to spot the speaker, only to realize it was he himself shouting his approval, even though he did not approve.)

After his speech Hitler is whisked away to a car out of sight. Sprawled on the back seat, he is drenched in sweat, reeking of vile emanations, exhausted, pale, his gaze unfocussed, twitching in throes, his clothes in disarray as if he clawed at himself. This description reminded me of Biblical accounts of John the Baptist channeling God’s will. It nearly killed John, but do it he must. Hitler, also, seems to be a messenger for something larger than himself. The agitator is himself agitated, as Harold Lasswell said all those years ago in ‘Psychopathology and Politics’ (1930).

Many were resistent to Hitler’s appeal like Geli herself who laughed in his face more than once.

Surprising to this reader was the cunning with which at times Hitler carefully tailored his message in the 1930 election so as not frighten voters. I had not credited him with that kind of calculation. But by that time, like the racism that infests contemporary American politics, it was so well embedded that it need not be said for it was communicated by signs and whispers. The red star of communism was also the Star of David. To attack communism was implicitly to attack Jews even if they were not mentioned.

Ron Hansen

False notes, there are a few. The most striking to me was the way Emile at the end seemed not to be bothered by Geli’s death.

Minor missteps? I wondered about the reference to a crossword puzzle in 1927 when the first crossword appeared in the ‘London Times’ in 1930, and the crossword being an Anglo-American invention it would have taken time to migrate to Germany. There is also a reference to a zinfandel-coloured carpet. I stopped at this, because the zinfandel grape skin is black and the use of it as a wine grape is American. (Yes, I know it has a long history and has been used in Croatia for centuries as a blender, but I doubt a German in 1927 would reach that far for a colour.) I also found jarring the reference to Kaiser rolls and Ferragamo shoes. The Kaiser roll is Austrian and may be named for a baker, not The Kaiser, and more generally called Vienna rolls. Salvatore Ferragamo started making shoes in Florence in 1927 and went bust in 1933, to be reopened in the 1950s, leaving me unsure that Geli could buy such shoes in a shop in Munich in 1930.

One contrast to Hitler of these pages is his contemporary Charles De Gaulle who also felt himself to be the saviour of his country and as a result grew a kingsized sense of his own importance, and yet he seems modest, even self-effacing in comparison. I read Jean LeCouture’s three-volume biography of Le Grand Charles years ago. De Gaulle did not use up people and then murder them when it was convenient as Hitler often did, like Ernst Röhm and perhaps Geli, among many others.

Category: Book Review

The Death of a Joyce Scholar (1989) by Bartholomew Gill

Dublin Chief Inspector Peter McGarr of An Garda Síochána (Guardians of the Peace) features in a series of krimies set in contemporary Ireland. They are rich in local detail and meticulously plotted with a variety of characters from lowlifes to highlifes. At times the inner compulsion to finish a job sees McGarr venture into Northern Ireland during The Troubles.

This installment in the series rests on James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses.’ Say no more. I had to read it. A scholar from Trinity College who lectures in the thriving business of Bloom’s Day is murdered. The suspects include academic rivals, jealous lesbians, a much put upon wife, a street gang, and … well that is enough.

While members of his team interview and re-interview these prospects, and walk over the Bloom’s Day tour time and again retracing both Leopold Bloom’s and Stephen Dedalus’s footsteps along with the victim’s, McGarr sits in the warm June sun in the garden at home on his annual leave reading ‘Ulysses’ in search of a context for all these people and their interactions, connections, meetings, conflicts, and associations. No Dubliner can admit to not having read ‘Ulysses’ so McGarr says he is re-reading it.

It is a clever premise and it is well executed.

The French Revolutionary Calendar (190)

22 Germinal 221

Nothing reminds us of the essential irrationality of the world than, there before our eyes everyday, the calendar.

Consider the numbers: the moon’s cycle is 29.53049 days which does not yield a nice set of months. Helios is no better. The earth orbit of Sol is 365.242199 days which yields 12.36827 months. These calculations were done by ancient civilizations around the world. Some of which had enough sense to stop there. The others formed committees.

(The hole gets deeper, if we ask what ‘a day’ is. And why, oh why, the seven day week? Let’s not go there, just now.)

The Julian calendar is one compromise, amusingly portrayed in John Maddox Robert’s novel ‘The Year of Confusion’ (2010) when Caesar tired of the squabbles among the expert committee he assembled to solve this problem. As always the defining feature of an expert committee is disagreement. After exhausting the treasure and patience of Caesar, the committee produced in 46 BCE a calendar that differed from the prevailing calendar by 0.0024 of a day! The committee did have enough sense among its cantankerous members to flatter its patron with that month ‘July.’

Pope Gregory repeated the exercise in the 16th Century with the result that the months range from 28 to 31 days, and inserted every fourth year a catch-up with Leap Year. No mathematical perfection there to please the Pythagorean in our souls.

‘Pope’ did I say ‘Pope?’ Yes, the Catholic Church owned that new calendar and completely colonized it with Saints’ days, feast and fast days, and more.

When the French Revolution ushered in the Age of Reason in 1793 it was as much a revolt against the Catholic Church as the Ancien Régime. All those saints’ and fast days had to go, and they went! They were rooted out right down to the calendar itself. The year of the Revolution was Year Zero, and that was 190 years ago and April is Germinal.

Another committee was formed….. It produced violent disagreements and incomprehensible technical disputes that led some of its member to the guillotine. How else to get a consensus but with a sharp edge? So the chair of many an expert committee has asked. Iain Pears’s charming Jonathan Argyll stumbles, as always, on just such a deranged committee chair in ‘The Titian Committee’ (1999), and though committee members are murdered one-by-one, the remainder are no closer to agreement. So true. Discordant unto death which in Latin, sort of, is ‘discordat usque ad mortem.’

The French Revolutionary Calendar made the irrational world, briefly, rational with decree after decree. The day, the week, the month, and the year, all had to change. And change they did (remember that sharp edge for those who clung to the forbidden, corrupt past).

As long as the earth spins, the irrationality remains despite what a committee in Paris does. The only solution is …. Yes, more committees. In the long outfall of the French Revolution, another French committee — inspired by the success of the platinum metre — tried again in the middle of the Nineteenth Century, but it soon fell apart and one member, the irrepressible August Comte, proceeded on his own with the Positivist Calendar with months named after Moses, Homer, Aristotle, Archimedes, Descartes, Fredrick the Great, Dante, … and Bichat. Bichat? [I don’t know.] Each week also got a name, e.g., Socrates, Confucius, Mohammed… So did every single day!

The Russian revolutionaries made their own calendar with the result that their own October Revolution retrospectively moved to November! It does get confusing when time is relative. Vide Einstein.

There came another committee at the League of Nations, which produced the International Fixed Calendar, dividing the year into thirteen months, each of 28 days with an extra day at the end. Not heard of it? Few have. It died with the League to be buried alongside that other bold effort at rationality, Esperanto.

The next effort to control time was when Adolf Hitler decreed that all of Nazi subjugated Europe keep Berlin time regardless of sun or moon. Megalomaniacs all.

By the way, the French Revolutionary Calendar is essentially a blank calendar template in which nothing ever changes, as per that phrase. The more things change, the more they remain the same.

The March of Folly (1984) by Barbara Tuchman

Having read three of Tuchman’s other books with relish, I moved on to this one. This book seems to this reader to be — superbly written, true to say — a glib festival of hindsight, with some self-indulgence thrown in.

It is certainly true that governments, the focus in these pages, persist in failed polices, at times with an irrational fervor. It was said of Phillip II of Spain that ‘no experience of the failure of his policy could shake his belief in its essential excellence’ and it could be said of many others, too. (The same is also true of the corporate world, too, but that is another matter.)

That painful, self-destructive persistence takes some explanation. But it is not to be had here.

First is the indulgence: She, the doyenne of (at least) popular history, starts with the Trojan acceptance unquestioned of that wooden horse. Hey, that is the Iliad, which is fiction at best and myth at least! People do foolish things in novels and plays as plot devices. A false note at the start is not a good start.

There follow flawless accounts from the vantage of Olympian hindsight of the popes generating the Reformation, of England precipitating the American Revolution, and the United States trying to destroy itself in Vietnam. Each is certainly a remarkable example of political failure, each replete with fascinating personalities and stories which she tells far better than most; likewise much of it has been well told many times before. Another telling adds what?

The method is to identify the critics and naysayers, whom history proved right, starting with Cassandra. The naysayers show that there was doubt and that there was an alternative that was eschewed as time and effort instead went into the mistake approach, which she calls policy, a term to which we shall return below. Therein lies the rub.

There are always, I repeat, always naysayers. That they existed proves nothing. That fate in perfect hindsight vindicates some of them is no help. The naysayers are very often wrong. How can one discern the true negatives among all those negatives?

Look around, anything you see, a building or an institution, a custom or a practice had its naysayers. There is a Newton’s Law in society: for every action there is a reaction, though not aways equal, and not always opposite. One day cricket, oral vaccines, art deco buildings, trams, credit cards, women wearing pants, all of these had loud, heated, persistent naysayers, and some of them still do, by the way. The book about the March of Naysayers would fill every library shelf in the world. The file would be too big for Kindle.

So what? If everything stopped because someone feared the worst, nothing would happen.

These pages offer no way to distinguish a naysayer worth listening to from one not worth listening to. Remember that Cassandra had been against everything all her life. Like that boy who cried wolf, she had spent her credibility long ago, that is part of the joke that Homer has, the one time she was right was of paramount importance, but everyone was way past hearing her.

The very word ‘policy’ is part of the problem here. In the 1970s political parties discovered this term and began to use it to distinguish themselves. They no longer had programs, practices, procedures, or even promises, let alone principles, they had policies. Of course, no one has ever been quite sure what ‘policy’ means as distinct from all those other ‘p’ words, but it does at least mean consistency. These policies have been painted in ideological and partisan colours. Once the opposition has embraced a policy, its opponents can no longer touch that policy. Thus is the political world divided.

The media has fixed onto that consistency and first tirelessly demands that a policy be stated, and then attacks the stater for any deviation from it. It is win-win for the media. Though political parties started this game they are now reaping the whirlwind.

Pity the politician who offers no policies. Yes, I know Margaret Thatcher scorned the word but she practiced what she did not preach under the heading of principle which in her case was ‘policy’ sans le mot.

Never mind that the world is a wild beast, that circumstances change, that reality testing often returns negative results, that the same response does not always fit all cases.

The standard is consistency.

It is as though, we should demand that medical doctors prescribe the same therapy for each patient, regardless of medical history, circumstances, prognosis, capacity, etc., rather than try to tailor the therapy to the individual.

Policy, that is, consistency, is itself sometimes itself the problem. Yet the demand is always for more policy, another policy.

If all this seems inchoate and abstract, turn to the example of Franklin Roosevelt who never tied his hands with either policies or principles but willingly tried this-and-that to find something that might work. Like Abraham Lincoln, Roosevelt had a goal and he steered toward that, though not always in a straight line, which meant going left sometimes and right other times. One imagines the meal a smirking ABC journalist, or a shouting Fox …. [journalist] would make of that today.

By the way, the best book on American involvement in Vietnam remains Neil Sheehan, A Bright and Shining Lie (1989). J. Paul Vann was Thucydides in this war, and when he died, Sheehan became his amanuensis.

Empires of the Dead by David Crane (2013)

This is a study of how one Fabian Ware created the funereal symbols we now associate with World War I and subsequent wars. The subtitle is ‘How one man’s vision led to the creation of WWI’s war graves.’

A reference to ‘war graves’ brings to mind green grass and ranks of white head stones to many of us. A reference to symbols evokes the solemn statuary say in Martin Place, or the dawn ritual of Gallipoli. Each of these and more trace back to Fabian Ware’s Herculean efforts.

Before World War I and Ware’s many efforts, British war dead were left were they fell, unidentified except by their absence at the next roll call, and buried in mass pits or burned with whatever fuel was at hand. The families of wealthy officers might (try to) retrieve the body or have a memorial erected at the site. That was it. And as Britain went so went the Empire.

World War I changed that. The industrial scale of the slaughter, even in the early days of 1914 made the war dead a visible, national issue. Scale tells the story. At Waterloo Wellington’s army had 3,500 causalities. One day at Mons 1914 the British Expeditionary Force had 35,000 causalities. These men were volunteers, but later it would conscripts usually organized geographically. One result was that the eligible manhood of whole villages and towns were destroyed in a battle, say at the hellhole of Ypres, whole cities.

Ware went to France in the earliest days of the conflict as a volunteer ambulance driver. He was a good organizer and soon commanded ever more ambulances and crews. Having been a student in France he spoke the language and loved all things French, apart from the Catholicism. He saw the way the British dead were ignored, and dealt with only as a health hazard or nuisance, and he went to work with a fury.

The metal dog tag, identity disk, was one result of his efforts, along with others. Tommys originally had a cloth name tag on the inside nape of the shirt. In heaps of mangled and rotting dead bodies no one wanted to wade in and cut those out, and most would have impossible to read. Given the staggering number of dead, the British authorities preferred to list the dead as missing to reduce the impact on public opinion. This conspiracy of silence outraged Fare and an outraged Fare was cold, methodical, utterly charming to win over allies, scrupulously rational in argument, and equipped with a mind-numbing array of facts and figures all heated by an evangelical zeal.

Like Thomas Edison and other aliens, Ware needed little sleep working all day driving the ambulance and all night compiling his arguments. In time he shifted his work from ambulances to identifying the dead, and marking and recording the sites where they lay buried.

There was much resistance to this effort but he pressed on and made allies as well as enemies. It is important to note that he was doing this often amid shot and shell. He gathered around him a dedicated team whom he taught, at night after an exhausting and terrifying day’s work, to speak enough French to ask locals about ‘Morts Anglais?’

His work transformed into the Imperial War Graves Commission, and again with a perseverance, tenacity, and wit beyond mere mortal he convinced the Empire dominions of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and India to leave it all to him.

He tried to control everything from the grass to the statuary that arose after the war. Tireless is the only word for it. Megalomania is another.

He convinced the French government early in 1915 to cede the land English soldiers were buried in to England! Imagine that. (See the note at the end for further explanation.) After the war that led to the consolidation (i.e., digging up thousands of graves and transporting the remains) into large necropolises like that vast expanse at Ypres. Every step was dogged by opposition, religious, familial, national, bureaucratic, political, institutional, church, racial, personal and Ware overcame them all. He anticipated much of this and was sensitive to religious and racial matters in handling the dead that seems enlightened by today’s standards.

In time most of this work was at a desk in London, but he would occasionally put down his pen at 6 pm in London and take the overnight boat-train to France for inspections. He descended on his field teams and more than once took a shovel himself. The men who worked for him hated these inspections for he was a strict taskmaster, but admired his commitment to the cause.

Like Steve Jobs he sweated the small stuff as well as the large.

What was that ‘cause’ any way? World War I, he thought, as did many others, was the last war and even more important it was an Empire war that united all the British peoples, all those naive volunteers, all those conscripts, all those lads from the Dominions, together they were everyman. Most had no wealthy families to care for them in death, and, as a Christian, death and those mortal remains had a sanctity that had to be respected. Moreover, the enormity of the death would discourage future wars, if only that enormity were brought home, he thought.

Death is a democrat; it takes all just as we are. Ware was an egalitarian at this level. He prevented many wealthy families from retrieving their beloved dead in contradiction to his vision of a single nation from all walks of life and parts of the world united in death. Imagine the outrage that caused. Only 10% of the one million British and Empire dead were identified, i.e., 100,000 but the families of many of those wanted their — son, brother, husband, nephew — to be singled out as an exception and some were willing to campaign for it and to pay for it. Thousands of letters to the Times denounced Ware in every way. Aristocrats petitioned the Palace and lambasted successive prime ministers. There questions in the House! Ware tried to explain his reasoning in response but the abstractions of equality or the vague promise that mass, majestic, silent cemeteries would stay the sword next time meant nothing to the bereaved here and now. The budget cutters in parliament snipped away as did Treasury. A perfect storm! How did he come through it all?

There is more to the story that is best read. And remember the Imperial War Graves stretched from Mesopotamia to East Africa to Gallipoli to Palestine to Greece to Italy and to the Western Front.

It is another of those cases that shows what a single person with intelligence and will — a Gulliver among the Lilliputians — can accomplish pretty much singlehanded, at the start, even in the face of vast bureaucracies (the Army, the Public Works Office, Treasury) that have other important priorities and in the face of an orchestrated and angry public reaction.

The story is much more powerful than the telling. The book is hard going. Many sentences I had to read twice to get the point. Obscure, elliptic, cryptic, inverted, recessive, these words come to mind in describing the prose.

Note. Ceding the land for cemeteries meant it cost nothing, but much more important it made the very land, say, at Étaples forever British even more permanent than an embassy.

In 1940 when the German army occupied Étaples it thus occupied British territory as much as the Channel Islands. The British flag flies there by right, not by courtesy. That is a gesture as thoughtlessly magnanimous as Winston Churchill’s in 1940 offering to surrender British sovereignty to France by combining the countries as one to continue the war. Another story there.

Ron Hansen, Isn’t it Romantic? (2003)

Recommended for fun

Take two late twenty-something French cosmopolitans, she Helen of Troy beautiful, he devastatingly handsome, on the outs and plonk them down in Seldom (Pop. 398), Nebraska and see what happens. That is the hypothesis of this short novel.

If Seldomites are surprised to see, first, Natalie walking down the dusty road with a roller bag, and then half-a-day later the wild-eyed Pierre burst out of a bus that had no business being there, they did not show it. Owen continued curating his shrine to BIG RED FOOTBALL, Carlo continued to think of nothing and no one but Iona who has ignored him (with some difficulty in this very small town) for years, Mrs. Christensen continued to experiment with jello and kool-aid, but Dick Tupper did notice Natalie, did he ever, and Iona did notice Pierre!

Natalie understands most English said to her full-face, using dictionary words, in proper constructions, and slowly without idioms. Not a common occurrence in Seldom. As a result, ….

Pierre gets about one word in twenty, which is enough when Owen… Well, read the book to find out.

Seldom, it turns out, has a few surprises of its own to offer. (I now know how CarHenge came about. If you don’t know CarHenge, maybe you should inform yourself by visiting: http://carhenge.com)

The setting is in the Sandhills where nature remains hard at work.

The result is charming, unexpected, delightful, and finally what you always knew would happen but not quite like that. Think of those screwball film comedies — It Happened One Night, Bringing Up Baby, My Favorite Wife, You Can’t Take It With You — from the 1930s and that is the right planet.

Steven Saylor, Raiders of the Nile (2014).

By my count this is volume fourteen (14) in Saylor’s Rome Sub Rosa series. In addition he has written two other novels set in Rome. He knows a lot about ancient Rome in the time of Julius Caesar. Though some of the novels are located outside Rome, in Egypt, in Lebanon, in Crete, in Cyprus, in Greece. They all feature the adventures of Gordianus, and some times members of his family, too. Gordianus is a working stiff whose odd jobs for those who can pay come to focus on finding things lost or stolen, or finding out things, like who stole them and why. He becomes known as Gordianus the Finder, because he good at finding those things.

A successful case of finding for Cicero lead to ever more work for wealthy clients. The result is ancient history. The Rome Sub Rosa series has gone on so long and been so successful that Saylor has now gone back to Gordianus’s beginnings. In this book Gordianus is a twenty-one year old pitched up in Alexandria on the Egyptian coast that being the best place to be to avoid conscription into the legions fighting each other in some kind of Roman civil war. No sooner does he relax to enjoy the easy life of Mediterranean sun than ….

Thus the adventure begins. Saylor tells a good story and packs it with interesting and highly individual characters. The leader of the Raiders is particularly well drawn, but there is a also a witch, and more than a few villains of different stripes. Then there is the decayed and decaying court of King Ptolemy IX (?). As always Gordianus is influenced a lot by his first friend.

Thus the adventure begins. Saylor tells a good story and packs it with interesting and highly individual characters. The leader of the Raiders is particularly well drawn, but there is a also a witch, and more than a few villains of different stripes. Then there is the decayed and decaying court of King Ptolemy IX (?). As always Gordianus is influenced a lot by his first friend.

At times the descriptions seemed padded and the tensions piled too high for fear of revealing how contrived, thin, and far-fetched the plot is. Having said that, I read it straight through in a couple of evenings.

Those new to the series might best start near at the beginning with Roman Blood (1991).

There are several other series of krimies set in Ancient Rome. The other one I have followed closely and like a lot is much more light hearted. That is John Maddox Roberts, SPQR (1991) and following. I have read fifteen (15) of them recounting the misadventures of Decius, who does not take things as seriously as Gordianus does. These two series are set in exactly the same time, and each has novels that feature Cicero, Caesar, Catiline, Crassus, Cleopatra, Mark Antony, Brutus, and their contemporaries. Reading them side-by-side is interesting both for the contrast in approaches and efforts to characterize these famous ones.

I stressed the individuality of the characters above because I have read too many krimies, including some set in ancient Rome, in which all the characters have the same speech mannerism, the same gestures, the same walks, etc. They seem to sound and look a lot alike. Not so for Saylor, or for Roberts either.

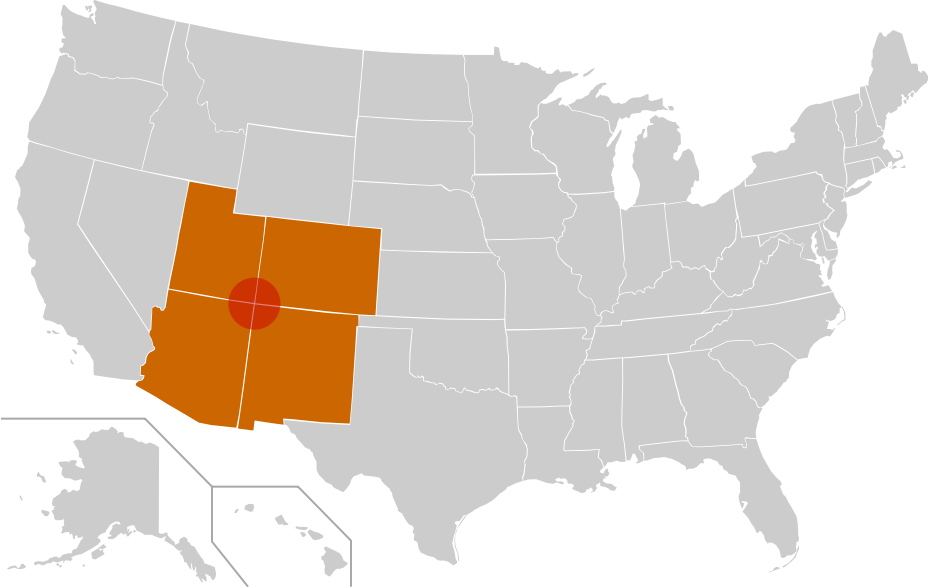

Anne Hillerman, Spider Woman’s Daughter (2013)

Recommended for all Hillerman fans and other krimie readers.

Tony Hillerman wrote twenty-five or more krimies set in Navajo country in the Southwest of the United States, more specifically in the Four Corners where Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah meet.

His protagonists were first Joe Leaphorn, then as he aged, he was joined by the younger Jim Chee. Leaphorn believed in science and reason in land of mystique and mystery, where rocks have names, and spirits inhabit shadows, or so it is said. Chee, though younger, finds much of value in the old ways of the Navajo, wind-walking, spirit-talking, and more. In each book the place is powerful presence, sometimes brooding, sometimes menacing, sometimes benign, and at other time indifferent.

His protagonists were first Joe Leaphorn, then as he aged, he was joined by the younger Jim Chee. Leaphorn believed in science and reason in land of mystique and mystery, where rocks have names, and spirits inhabit shadows, or so it is said. Chee, though younger, finds much of value in the old ways of the Navajo, wind-walking, spirit-talking, and more. In each book the place is powerful presence, sometimes brooding, sometimes menacing, sometimes benign, and at other time indifferent.

The Old Ways of the Navajo may be gone but they are not forgotten by the legion of archeologists and anthropologists who overrun the countryside. Moreover, there is a market for the rugs, for the pots, and even for the oral history of the Navajo. Then there are other indians, occasionally old enemies.

Into this milieu Anne Hillerman has stepped. Tony died and she sat down at the keyboard and three year later produced her first Leaphorn-Chee book.

It is a fine addition to the canon. Leaphorn and Chee remain as ever, and Bernie Manuelito, who was Chee’s girlfriend and now his wife moves more to centre stage. Like Joe and Jim, she is a member of the Navajo Tribal Police.

It is a fine addition to the canon. Leaphorn and Chee remain as ever, and Bernie Manuelito, who was Chee’s girlfriend and now his wife moves more to centre stage. Like Joe and Jim, she is a member of the Navajo Tribal Police.

As always there are many policing jurisdictions, to confuse this reader, but refreshingly for once the FBI agents are not treated as drooling idiots. The story opens with a shooting that baffles one and all. The false leads and blue herrings are many. It always comes back to those Navajo artifacts, it seems.

Readers who have followed Leaphorn and Chee all these years are advised to take this one on its own merits. There is plenty to keep a reader engaged.

We drove to Monument Valley a few years ago and along the way saw some of the Four Corners, like no other place for the scale and remoteness, and the geology.

Milan Kundera, ‘The Unbearable Lightness of Being’ (1984)

In anticipation of a trip to Prague, I read some Czech literature, starting with this one.

Milan Kundera

I liked the proposition that life is light, and knowing that causes anguish. ‘Lightness’ means that life is produced by chance, accident, coincidence, mistakes, and so on. It all could just as well be otherwise. There is nothing profound, fated about what happens. Our individual lives are nothing much and we might as well enjoy what we have since there is nothing deeper to it, no world-historical meaning, no kismet, no divine plan. Just living and breathing, as Karenin, the dog, does. Lightness = liberation.

Only when Tomas and Tereza shed all their past lives and move to the country where the high point of the day is a walk in the woods with Karenin do they find happiness together. Though by then they are both so worn and defeated, she by weightiness and he by lightness, that they are barely aware of it.

But knowing that life, that one’s own life, is trivial and insignificant can disturb some. In reaction they search for weight, for meaning, in political action, in religious conviction, in martyrdom, in intellectual snobbery, in technical argot that excludes others, and so on.

There is much food for thought here. Moreover, sprinkled throughout the book are ruminations on the consequences of the Prague Spring of 1968, the subsequent Russian intervention, and the reactionary Czechoslovak regime that followed. Tomas and Tereza flee and then return, and that seems a kind of fate and the consequences are certainly heavy. Life may be light but the weight, like gravity, is always there. It cares not whether one denies it.

Tomas falls from social grace, from a skilled and valued surgeon, to a general practitioner, to a pharmacist, to a window cleaner, to market gardener. Evidently Czechoslovakia had so much educated talent it could afford to train its window cleaners to be surgeons.

Tereza’s fall is lateral, from budding photographer who documented the Prague Spring and then the Russian intervention to tell the world of the hopes of the former and the crimes of the latter, only later to realize her pictures meant to celebrate Czechoslovak courage and fortitude were used by the Secret Police to identify victims. She tried to be heavy in taking the photographs and discovered the law of unintended consequences took over. It is the one law we all obey.

I cannot say I enjoyed reading the book. Though the substance as adumbrated above is compelling, the storyline seems, more often than not, an adolescent idea of life with Tomas and his parade of willing women who never seem to want anything from him but an hour of sex which is completely light in that it never has any consequences. An endless supply of them seems to await only his nod. That is the major key in the novel, and that no doubt explains why the film was made, an excuse for a parade of sex. That project would appeal to the boys with arrested development who dominate the film industry.

That and the side tracks with Franz and Sabina, and some pontifical interpolated pages detract from the momentum of the novel.

Equally, the fractured timeline that moves back and forth on itself is metaphysical but not motivational to the reader.

It is indeed a modern novel with its broken and curled timeline, its unreliable narrators (Tomas and Tereza, among others), its inconsistencies, its multiple points of view, and its abrupt shifts of place, as well as time.

Tried to read it before and lost interest in one of the sidetracks. The film passed in front of my eyes on a long flight once.

Robert Sheckley, The Status Civilization (1960)

I read a lot of science fiction, and I certainly read novels by Sheckley though I have no recollection of reading this one. The title that chimes with me is ‘Journey Beyond Tomorrow.’ Though the cover reproduced below is familiar.

I saw a copy of ‘The Status Civilization’ last month, in of all places, The Museum of Democracy in Canberra. In the once parliamentary library in the Museum there were a number of utopian and dystopian novels. (I thought them out of place in absence of any books on the subject of the Museum – democracy.)

The name Sheckley meant something to me so I put the Dogs of Amazon to work in tracking down a copy. A lot of 1950s science fiction is now being reprinted so we can re-visit them and I got a copy and read it in a day. It is slight book of little more than one hundred pages.

It posits a world consistent with Thomas Hobbes’s state of nature with some shadowy political institutions. The motif is familiar, Philip Dick, ‘Clans of the Alphane Moon;’ Mack Reynolds, ‘Equality;’ John Carpenter, ‘Escape from New York;’ and more.

The plot twist at the end was mildly amusing but quite inconsistent with all that had gone before, making the whole broken-backed. The point was how easy it is to misperceive a distant reality, and maybe that made more sense at the height of the Cold War than it does now.

Still it was a tonic compared to James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses!’

Details at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Status_Civilization