My project on presidents of the United States extends to some also rans, and this is the first one I have read about. Others on the also ran list include Henry Clay, Harold Stassen, George Wallace, and Eugene Debs. A varied lot. I also have my eye on Jefferson Davis, an American president who was not a president of the United States, like Sam Houston. I also include the last Hawaiian monarch for the future.

Category: Book Review

Mr. President Fillmore

Millard Fillmore: Biography of a President by Robert Rayback (1992). Recommended.

The Thirteenth President. Another succeeding vice-president who did not win an election, like John Tyler before him and Gerry Ford after.

Famous for: Maynard G. Krebs referred to him as Fillard Millmore to the repeated and visible annoyance of Mr. Promfritt, and he was also mentioned in ‘What’s up, Tiger Lily (1966)?‘ Students of Cultural Studies will grok these references; others will turn to Wikipedia.

Though Fillmore was anti-slavery he was intimidated by the magnitude of freeing seven million slaves and hoped for a gradual method and so did nothing. In an effort to maintain its North-South axis to make it a national party, the Whig party in 1848 capitalized on Zachary Taylor’s fame as a successful General from that era’s invasion of Mexico. Taylor was a Louisiana slaveholder. To balance the geography and the position on slavery, Fillmore agreed to join the ticket as a New Yorker who was anti-slavery but not an abolitionist.

Taylor treated Fillmore as every vice-president was treated. Ignored him entirely. Then Taylor took ill after a year and four months in office and died. Overnight Fillmore became president.

He had served in the New York state legislature, he had served three separate terms in the House of Representatives in Washington D.C., and he had been comptroller (chief financial officer) of the state of New York. He brought to the Presidency long experience of finance which he was good at, patience at working with committees, and a national outlook born of his long association with the Erie Canal and commerce along the shores of the Great Lakes.

The burning issue of the age was the existence, perpetuation, extension, or extinction of slavery, and its evil twin the tariff, which the South felt taxed it for public improvements in the North. The admission of new territories and states in the West was the kindling for these issues. Why? The addition of new senators would disrupt the balance of power in that body.

Fillmore supported, defended, and executed the Compromise of 1850 as a way to reduce the flames of insurrection, civil war, rebellion, invasion, riot, and the like. That meant enforcing the draconian fugitive slave law. Just as no state can decide which laws to obey and which to ignore, neither could a citizen, let alone the first magistrate, decide which laws to obey and which to ignore, despite his personal feelings, he reasoned.

As president he promoted industry, innovation, commerce, and business in the hope that national prosperity would lessen the heat in the extremities of the body politic. He encouraged trade with China and Japan and supported a railroad and then a canal across Central America to speed trade with the Orient. He warned first the French and then the British off Hawaii.

The aspirins of commerce did reduce some of the fever pitch but the effects soon dissipated. In 1852 one of the architects of the Compromise of 1850 proposed scrapping it, namely that Little Giant from Illinois Stephen Douglas. Go figure! All the old grievances and animosities re-emerged as if preserved in amber with every details in place. Nothing forgotten; nothing forgiven.

Should Fillmore seek the Whig nomination for another term in 1852? He dithered like a Libra though he was born a decisive, if lazy, Sagittarius. In the end Winfield Scott was the Whig nominee and was trounced by the Democrat Franklin Pierce.

Fillmore went into retirement in Buffalo, but his wife died within a month of leaving Washington DC and his only child, a daughter, a few months later. Thus at a loss he travelled through Europe and Asia, and flirted with re-entry politics.

By 1856 the Whig party was moribund and Fillmore joined the American Party, the political front of the Know-Nothing Movement [think Tea Party] and the rabid anti-Catholicism which was a reaction to the tidal waves of immigration occurring in East coast cities like Boston, Philadelphia, Hartford, Brooklyn, New Bedford, Providence, Trenton, Baltimore, Wilmington, Charleston, New York, and more. It was also anti-black. His vice-presidential running mate was Andrew Jackson Donelson, a nephew of Andrew Jackson. Fillmore evidently thought he could tame these nut cases [think John McCain] and discovered he could not [ditto John McCain]. He came a distant third to James Buchanan and John Frémont. His vote made no difference to the outcome.

That ended his political career. He made another European trip and was much feted as a former president, crossing paths with The Little Magician, Martin van Buren, who was in Europe. Fillmore returned to Buffalo and in time re-married and became a man for local good works. He was on every committee for a hospital, a school, an orphanage, a library, a bridge, a hard road, a railway crossing, a sewer line, a pier on the Erie Canal, and the University of Buffalo where he served as Chancellor raising funds for many years. Many of these committees met in his home and he was the real and titular chairman of many. How many ex-presidents have done as much tangible good, I dare not ask.

Though he disliked Republicans for happily embracing a Northern only party (Lincoln got not a single electoral vote in the South and no popular votes beyond Maryland and Kentucky) which he feared would, as it did, lead to civil war. Once the civil war came he organized a home guard of the superannuated and paid for its uniforms. There were recurrent rumours from the outset of the Civil War that Great Britain would intervene from Canada to revenge itself on the United States and so this guard was as much a message to British officials in Canada as to Confederates.

At war’s end, he advocated moderation toward the defeated South but his voice was no longer heard.

Despite those wits Woody Allen and Maynard G. Krebs, Fillmore did a great deal of good first by holding the union together in peace for his term, and then materially in his home town of Buffalo. His name is found on many schools, hospitals, bridges, and the like. A honour that has so far escaped Mr. Krebs. Of Mr. Allen, I (prefer to) know not.

The book is well documented. When an assertion is made there is a reference to a source. The first hundred pages or so are pretty dreary as it traces his origins and early life, but the prose sharpens as his political career unfolds. The last third of the book offers some well judged observations and striking turns of the phrase.

It is part of series but does not read like a completed template the way the presidential biographies read in the series edited by Arthur Schlesinger, Junior. Rayback was professor of history at Syracuse University when the book was published.

James McClure, The Artful Egg (1984)

Recommended for Krimieologists.

A rattling story that reaches top speed by page two.

The irascible, clumsy, crude Inspector Trompe Kramer sets off in all directions at once with Sergeant Mickey Zondi in tow to find out who killed the Republic of South Africa’s most famous resident, dissident novelist, loosely based on Nadine Godimer I suppose. There is a passing reference to André Brink for good measure.

The manners and morés of apartheid society are there, and Kramer and Zondi comply just enough to get by. There is never any moralizing about it, though the English liberals who surround the novelist have plenty to say.

There are marvelous moments as when Kramer, who has never read a book, discusses Shakespeare’s Hamlet with an English-speaking professor of English, who delights in all of Kramer’s stupid remarks as deep insights into the Bard. The reader is not quite sure which one is the clown. Nice. Kramer’s grasp of English is schoolboy standard.

There are some nice moments with both Zondi and Kramer realize the polite, shy, and reserved Vicki is more than she seems. It is just a flicker at first, and neither of them dwells on it. Nice.

As usual in this series the typical Boer police officer is portrayed as several levels below a Mack Sennett Keystone Kop. But given that it is slapstick some of it is hilarious.

The society is rigidly structured by race in everything. There is virtually no interaction between the Boer white majority and the English white minority. Kramer speaks English but not as well as his mission-educate Bantu sergeant Zondi.

I found the subplot involving the Indian postman a tiresome distraction when I realized it was not contributing anything to the plot but is evidently supposed to be comic relief. Had I been the editor I would have cut it after the letter is delivered in Chapter One.

Barry Maitland, The Marx Sisters (1994).

Recommended for krimieologists.

This title is the first in a continuing series featuring Chief Inspector David Brock and Sergeant Kathy Kolla. It is assured and has a light touch though the subject is murder.

The sisters are indeed distant relatives of Eleanor Marx (wife of Karl) and that figures in the plot in several ways.

There are many blue herrings, as Hercule Poirot says when the English idiom fails him, from a son eager for an inheritance, a developer who wants to build a giant building, an angry neighbor. Perhaps the dominant character is a place, Jerusalem Lane where the sisters live. It is marvelously invoked, though my London A to Z does not list it, more’s the pity.

The police make mistakes and pursue some of those blue herrings. Even the inscrutable Brock sometimes blunders. Fallibility appeals to me.

There is a delicious portrait of a solipsistic and unscrupulous scholar who reminded me of some I have known.

This first volume in the series is mercifully free of Kolla’s endless capacity for self-pity that I find distasteful in the latter volumes, though the seeds are there. Too often Kolla’s main interest is Kolla. No doubt some readers find her incessant self-doubts and uncertainties attractive but they are too narcissistic for this reader.

For more information go to:

http://www.barrymaitland.com/index.html

Personal note. Like many others, when I first used the Reading Room at the British Museum I sat in the seat Karl Marx habitually used.

James Benn, Death’s Door (2012)

I enjoyed the portrayal and factions, bureaucratic turf wars, national animosities, divisions within divisions within the micro-state of Vatican City, only made sovereign by the Lateran Treaty with Italy (Mussolini) in 1929. The Vatican police force is divided into three, the neutral, the fascist, and the anti-fascist. The Swiss Guards have real uniforms and weapons. The Vatican police and Vatican’s Swiss Guards are two separate groups and not friends. Most of the Swiss are Sweizcher Deutsch who look down on the Italians in the police. The police are called gendarmes for some reason. Our hero interacts with the gendarmes inside the Vatican, while the Swiss Guards patrol the line of demarcation.

The book offers an explanation of Pope Pius XII’s quiescence in 1943 anyway. By then there were 5000 Jews, downed Allied airmen, anti-fascist Italians, salted away in Vatican City and in Vatican properties (part the Vatican’s sovereign soil by the Treaty) elsewhere in Rome. The Pope’s vast summer palace in the hills outside Rome was home to another 15,000 refugees. Silence might be the best way to avoid interesting the Germans in them.

Moreover, with Mussolini reduced to a puppet up North and only the most extreme Italian fascist left in Rome along with the occupying Germans, there was the danger that the Germans might decide to take the Pope north for his own safety on the pretext of Allied bombing, exposing not only the refugees in the Vatican but also its many treasures and destroying its studied neutrality. A low profile might be best so as not to give a pretext. Hmm, but if the Germans had a mind to do that, a pretext could be conjured as it was many times before.

Also liked the tension on the white painted line of demarcation in the square in front of the Vatican that still marks off the sovereignty of the Vatican, but in these days it was patrolled by the Swiss Guards on one side and the German army on the other. I liked the geography of the buildings and gardens in the Vatican, including the Vatican radio.

The evils of the Gestapo and SS were old news. Our intrepid hero was cardboard as were most of the other characters. Though there were a variety of characters and they did differ, I admit. I liked the way some of them reacted to being trapped in the gilded cage of the Vatican when the war cut them off, like the American diplomat who disappeared into the brandy bottle.

Some interesting characters appeared but not enough was made of the artful scrounger, the butler John May, Detective Cipriano of the Vatican police, or Abe the pilot lock-picker.

Not sure what to make of the good German, Remke and his team. Doomed, of course. The Italian OVRA sadist was a drooling stereotype as was the evil Croatian bishop.

The villain was hard to credit.

Billy tried too hard to be a reverse snob. Most of his wisecracks were tired sixty years ago. As is usually the case his backstory was simply a distracting filler.

Many of the events take place in the German College in the Vatican but no ever connects this with the Germans outside and there seem to be no Germans in the Vatican. No German cardinal or archbishops or bishop.

Nothing about the Italian day workers who come to work every day.

The prose is workmanlike.

The Billy Boyle books each have different setting so that is goodbye to the Vatican. But I will try searching for Vatican krimies.

Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and The War Years (1925).

There are scores of Lincoln biographies. I have long been dimly aware of a multi-volume biography of Abraham Lincoln by that poet of the Great Plains, Carl Sandburg, but eight volumes was much more than I wanted. In the oral version from Audible it runs to 44 hours. However I did notice that there was a one volume abridgement. That then was the obvious choice. A biography of the most famous son of Illinois by the most renown poet of Illinois.

All the well known stories are there and I shall not retail them.

New to me

Length and variety of his militia service

Travel down the river to New Orleans

Early and unequivocal objection to slavery on moral grounds in public statement occasioned by pursuit of runaways slaves into illinois

His gradual drift into politics because government could build bridges, dig drains, etc that this small community could never do. Local improvements, they were called at the time.

Saw Zachery Taylor and William Henry Harrison who both later became president.

By 1837 Lincoln opposed slavery on moral grounds, but accepted it in the South because of the Constitution.

As a mediator he learned from his father’s example of dealing with eight children of a blended family in a one-room cabin. Defuse the situation and illustrate with humor

He spoke up on local improvements and because he had learned to read and write, others who could not do either turned to him to prepare petitions.

He became a state representative as Whig, worked hard at committees, reports, speeches

He saw and served in some run away slave case in Illinois.

He was a one-term congressman as a Whig, campaigned for other Whigs in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Kentucky.

Lincoln voted several times for the Wilmot Provision to prevent slavery in new territories and states.

In his notebooks Lincoln puzzled over the morality, constitutionality, legality of slavery in whole and in part for years.

He concluded it was immoral since 1837, only indirectly constitutional in the States that had it a when the constitution was agreed, but fugitive slave act was legal, made by congress.

So he wanted to stop spread of slavery to other or new states, stop slave trade bringing in new slaves, but not for ending it since it was legal and partly constitutional in South Carolina and its ilk and since there was no way to cope with one million slaves in seven states who would be made free overnight and impossible to work out how to do it gradually, So on practical grounds there was no solution. Abolitionists seemed to have no plan for what to do if slavery were abolished, rather like all the Greens today who scream immediate action without a thought for consequences. He would have preferred to keep the Missouri compromise but it lapsed with the Compromise of 1850 which was a hodgepodge of deals and concessions much too delicately balanced to last.

Anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic Know Nothing Party arose (reminds me of Tea Party!)

Lincoln supported immigrants to vote, to get citizenship quickly and they voted for him.

The number of immigrants at the period is enormous 12,000 a month in Chicago, not all stayed there but went on to Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska.

When the Free Soil Party morphed into Republicans at Ripon Wisconsin (an event no longer celebrated on the Republican National Committee website, such is the pernicious influence of the ideologues) Lincoln had no baggage as an old time Whig, he was from the West and fresh and energetic, and he wanted the presidential nomination in 1860.

He seemed to like being at the centre of things in Illinois legislature and got the ambition.

In a four-way race he won the electoral vote on the popular vote in the larger, northern states. The Southern states started seceding from the Union long before he took the oath of office in March 1961.

Lincoln the president was slow, thoughtful, pragmatic, thick-skinned, patient, mindful of his limitations and those of others. Not to be stampeded by cabinet, nor by generals, nor by the press.

Scurrilous animosity of many in the House and the Senate is hard to credit but it is palpable, and only occasionally silenced. Even Lincoln’s re-election did not shut them up. Th calumny heaped on him by Senate Republicans, war democrats, peace democrats, abolitionists, to say nothing of the Confederates beggers belief.

The restraint in the Emancipation Proclamation was to try to prise the three border states and Delaware away from the Confederacy by not confiscating property of slave holders in those states.

He found slavery objectionable not because of the equality of blacks, but for the debasement it brought to the master. More and more though he did realize that blacks were not only sentient but more. Frederick Douglas and other blacks he met lead him along this path, as did they blacks in the Union army, about 200,000 of them by 1865.

Lincoln’s 10% plan. Those states partly occupied by Union army in 1862 and 1863 like Florida, Louisiana. If petitioned by 10% of males citizens computed against 1860 census he proposed that these state be permitted to form a loyal Union government and to rejoin the Union. For example, Louisiana would have a rebel government in Shreveport and a Union government in New Orleans.

Congress would not agree for a variety of reasons: for some the states which seceded had committed suicide and were no longer states at all, for some these states should be treated as conquered territory under military occupation, for some this plan was a sneaky Lincoln way to get more Republican voters first to get re-nominated instead of Chase and then to get more electoral votes in the general election, for some the were constitutional and legal technicalities that would take ages to be resolved through courts. Were now free blacks to sign these petitions? The House and the Senate would not seat representatives or senators from these ersatz states for all of these reasons and more. This was a mistake, Lincoln thought, because it made fighting on the only choice for some who might otherwise lead a reconciliation. The war between executive and legislature never ends, and there are few truces.

Later in the war Lincoln also tried to set up local governments in East Tennessee that had always been loyal so to protect the loyalists from revenge of losing Confederates. Again congress resisted on analogous grounds.

Lincoln toyed with offering to buy slaves remaining in Deep South to end the war. He claimed it would be no more expensive in money than continuing the war and it would save lives and the destruction of property.

Lincoln ignored distinction of church and state several times a national days of prayer.

Scores and scores of personal petitions to Lincoln and he heard and read just about all of them, and often conceded the exception they asked. That bothered me because I have always resisted making exception for the one in front of me because (1) there many equally placed who were not in front of me for whom I was going to do nothing and (2) I did not want to encourage others to present their petitions to me. My thought was that if here is a reason to make an exception it should be written into the rules. Sandburg does nothing to analyze or assess Lincoln’s response to these petitions.

The endless flood of office seekers even in the dark days of 1864 would be enough to slay a lesser man.

Of all the wonderful remarks Lincoln made, these two say it all.

1. ‘My policy is to have no policy’ (p. 239). An oft repeated remark. Imagine saying it today.

Lincoln was not an ideologue. His goal was to preserve the Union and on Monday that might mean X and on Friday it might be doing -X. If an analogy serves considers a sail boat. To make harbour amid winds and tides sometimes a captain must oversteer to port and at other times oversteer to starboard. These is no inconsistency in these variations, though every immature journalist will declare that there is, having face no bigger challenge than finding a parking place at work.

2. ‘Mr. Moorhead [a very young know-it-all], haven’t you lived long enough to know that two men may honestly differ about a question and both be right (p 660)?’

This remarks explains why he was not an ideologue as per the first remark.

In these 800 pages there is no poetry, and very few examples of Sandburg’s capacity to elevate the mundane to majesty with the sheer energy radiating from the page in his poetry. He also lapses into the present tense in depicting the assassination.

There are too many chapters which list events that do nothing to develop Lincoln, the man, or Lincoln the President.

After the early years the book is about Lincoln the president. No much about the man, relationship to wife or children. Was he religious, I cannot tell? Nothing about attending church and only show him once or twice consulting the Bible, but instead relying on his folksy stories, though the moral of many of these stories could have illustrated from the Bible.

It has no sources or bibliography. Opening preface eschews footnotes.

Barbara Tuchman, The Guns of August (1963)

Highly recommended.

The second Tuchman book I have read. This by legend is the one Jack Kennedy read and it scared him when he thought about nuclear weapons.

One of Tuchman’s major themes is that a plan carefully made in detail and extensively supported takes on a life’s of its own. If a small shove engages the plan, then it takes a super-human effort to divert it, stop it. (When President Kennedy abruptly gets up from the table and walks out of the room while the Air Force generals are arguing for bombing Cuba in the film ‘Thirteen Days’ that is one example of the effort to resist a plan in the face of enormous pressure.) In 1914 the Germans had the most extensive and detailed plan for war of all time and so were the most bound by it. It specified the train cars platoons would ride it and at what place and time they would, dismount from Mobilization Day (or M40) plus 40 in Paris. Once the plan was initiated everyone knew what to do and set about doing it. Belgian resistance which had been set at 0 in the plan broke down the schedule and traffic jams resulted. The perfect plan contained an erroneous assumption. But that dislocation simply made it more imperative to get back on schedule, not to think twice about the plan. The General Staff set to work around the clock to re-route trains, to re-supply units, to to find alternative roads, to shift rolling stock, and so on.

Another general theme is the difficulty of getting anyone to obey orders. French, German, Russian, and English generals refused orders, stalled, deliberately misunderstood, or willfully rendered themselves incommunicado. Even when the superior officer came and delivered the order face-to-face in person the response was sometimes tomorrow, not just yet, or no. At times it was impossible to replace this general so he stayed in command and did not move. The Prussian General Francois waited and stalled and stalled until he was ready to move on his terms. The Prussian Von Kluck ignored his order and improvised in the hope of a magnificent coup and blundered.

In the same vein, she stresses the general confusion of war. The German Chief of Staff had little idea of what the situation with his own armies was, let alone where the French or English were and in what force. Ditto for corps and division commanders.

Another theme is the logistic of moving regiments, divisions, corps, and armies. The staff work was crucial. To move 70,000 armed men with artillery and other equipment takes a very great deal of detail and direction, a timetable for movement, an allocation of roads or railroad cars, fodder and food along the way, and much more. It all makes Sydney’s Town Hall Station at peak hour seem organized.

The tangled web of secret treaties, each with its conditions and conditionals, made it difficult for anyone to predict what would happen. And even where there was a simple and clear treaty inevitably it was made by someone else a few years ago and the question of the will of the current incumbents to live up to it arose.

The disobedience gave scope for individuals to make a difference. Her study by the way is all at the command level, generals and up, not grunts.

Of personalities, the Kaisar seems a loose cannon who wanted to show the world Germany was a great power. The French general Joffre made many mistakes, none of which he ever admitted, but was a rock of calm and optimism. French, the English commander, lost his nerve not even a personal visit from Kitchner could stiffen him.

The contradictory character of orders plays into the disobedience. A general is ordered to attack but cautioned not to expose his flank. A general is ordered to be aggressive but not to risk defeat. Which part takes priority, aggression or risk avoidance?

Galiani seems to have been the man for the hour at the Marne. His idea of a long meeting was 15 minutes, all else was action. He was a general without an army for the most of the time but that only slowed him down, it did not stop him. The taxi cabs were but one of his initiatives.

King Albert of Belgium was ready to fight from the first and did not relent when the Germans started shooting civilian hostages. Even a German effort to buy him off for an enormous sum was rejected.

The Russians fulfilled their French alliance by attacking long before they were ready and that led to be a major defeat from which they never recovered, but it did draw off two German army corps from the invasion of Frances and that helped weaken the German advance in the West. There are many ifs and might have beens.

Even the most bellicose commanders, when the order to attack came, hesitated, trimmed, temporized.

She has many masterful turns of the phrase. Impressive research and synthesis from original sources. The scope is everything that happened in August 1914, well literally from the July assassination to the started of the Battle of the Marne in mid-September.

The tactical of manuals of the Russian army placed little emphasis on shells for either rifles or cannons, but instead stressed sabres and bayonets. The German manual told attackers to run 20 seconds then fall down while the enemy fired every 20 seconds. After they have fired get up and run again. But the fire rate was 8 seconds as it turned out.

Though most of the weapons, artillery and machine guns, that dominated World War I were used by the Japanese against the Russia in Asia, and dutifully reported by the European military attachés who observed the Russo-Japanese War, virtually nothing of that made its way into the manuals, the ministers of war, or generals.

Personal rivalries and antagonisms between generals often spoiled plans.

The capacity of politicians to dither in the hope that the crisis would dissipate of its own accord in England and France is worth reading. Even with the Germans 40 miles from Paris no democratically elected office holder would permit General Galini to demolish building to create firing lines. Instead they argued over who would pay compensation to the owners and questioned the necessity of destroying bridges to impede the German advance. Galini wanted to mine all the bridges over the Seine and delegations of historians opposed him. There was very little singular focus even with the Barbarians at the gates.

Speaking of barbarism, the German atrocities in Belgium did occur and they were systematic.

The Zimmerman Telegram

Barbara Tuchman, The Zimmerman Telegram (1958). Recommended.

It is far fetched and yet true story of how the Kaiser’s Germany tried off-and-on to encourage animosity between Japan and the USA, between Mexico and the USA and then an alliance between Japan and Mexico against the USA, or between the Japan, Mexico, and Germany against the USA to keep the USA out of European affairs, especially in the years for American neutrality in WWI. The various schemes were launched independently by several German agents and government departments promoted a Japan-Mexico alliance funded in part by Germany to keep the USA locked into North America. It included either a Japanese invasion or inflitration through Baja California. The prize offered to the Japanese would be the Philippines and Hawaii and to Mexico the return of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. If Mexico could be won over it might stop the flow of Tampico oil for USA navy and might offer naval basis to U-boats along with the oil.

In World War I Japan had allied itself with the England and France, but once it had occupied the German possessions — Guam, Samoa, and the Marshall Islands — in the Pacific it had no further interest in the war. Germany was willing to give those up for Japan to dabble in Mexico. There was even at one time mention briefly of a formal military alliance of Germany, Japan, and Mexico.

The Japanese encouraged the approaches to see what was on offer, but never seemed to be seriously considering it. But simply being receptive was disturbing intelligence in Washington. The real value of Japan to the Western European alliance was that it secured Russia’s Asian border so it could concentrate its armies in Poland and not have to hold back some to guard against a Japanese attack and replay of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904. Accordingly, to the Western Allies the goal was to neutralize Japan one way or another. Anything that jeopardized that neutrality was dangerous. Hence the German efforts to do just that.

At the time Mexico was a cauldron of vying war lords throughout this period: Villa, Huerta, Carranza, and others. Each willing to promise anything to get arms and gold, each hating El Norte. (Well that just about sums up a great of Mexican history to today.)

President Woodrow Wilson is presented as an inflexible idealist who could not shape his manner, means, or message to the circumstances. He worked from elevated first principles for all times and all places, and so not suitable for any particular time or place. His invasion(s) of Mexico was for its own good! He found it very frustrating that Mexicans did not realize that and acquiesce. His goal was regime change! History is repetitive. He was quite upset that Mexicans resisted and united against his invasions.

Colonel House features largely in this story as one who enjoyed playing the game that he often lost sight of what it as all for. Because he enjoyed wire pulling so much, he overestimated his own influence.

Wilson ignored the reports and advice of diplomats because he knew they did not imbibe his goals of world peace and were concerned only with American interests, including business interest in Mexico and with Germany. Instead he relied on House who never said anything Wilson might not want to hear.

Robert Lansing came early to the conclusion that war with Germany was inevitable. He was reading the diplomatic reports and realized Germany would never compromise to make peace.

The most astounding thing was that Colonel House convinced Wilson to let the German embassy in Washington DC use State Department cables, during US neutrality, to communicate with Berlin and for the German foreign office to reply by the same means ostensibly to consider peace terms but in fact it was to avoid British intelligence surveillance in communicating to Mexico from Washington DC. The Secretary of State, Lansing, to his credit resisted and demanded a written order from Wilson each of the many times over weeks, because it violated neutrality.

Even after the Zimmerman Telegram was revealed the Germans kept using it this American channel. It seems never to have occurred to any German that the code had been broken somewhere. They tried to trace the leak and the English tried to conceal it. Zimmerman, by the way, was the German foreign minister.

The Zimmerman Telegram was timed to coincide with the launch unrestricted submarine warfare with the up of an uprising in Mexico and the prospect of a Japanese attack on The Philippines, or Hawaii, or even California to paralyze the USA. The German General staff estimated Britain could only hold out six months with unrestricted submarine attacked. If the USA was pinned down for a time, it might be long enough to compel a British surrender. Without Britain, France would, the Germans supposed, fall over.

The declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare depended on having 200 U-boats operational to go to unrestricted warfare to cover the sea approaches to Britain. When that number was reached, the declaration was made.

The British had broken the code and since the German sent that Telegram three times, such was their confidence in the impenetrability of the code, once via the neutral Swedish diplomatic route which the Swedes offered to Germany throughout the war in violation of their own neutrality, via radio from Berlin, and by Telegram to Washington D.C., they got it. The British wanted to conceal the fact that they had cracked the code so that the German would keep using it. So they had to figure out a way to reveal the message to the USA in such a way to prove its authenticity but not so much as to reveal how the USA came to have it. That is a convoluted story best read.

Yet there is more. The authenticity was denied by American pacifists like Robert LaFollette. The Senate was set to block. Then Zimmerman in Berlin called a press conference. The opening question came from a pro-German American journalist who said ‘Of course,you are going to deny it….’ But no, Zimmerman said, ‘I can’t deny it because it is true.‘ End game! Then he proceeded to split hairs about whether the putative alliance was to apply before or after the USA entered the war. Too late, the admission undercut the deniers in the USA.

Let’s count the blunders there. Zimmerman did not need to have a press conference. If there was one, he could have sent someone else. If he went, he could have stalled, temporized, or prevaricated since time was the essence. Remarkably he continued in office.

When the telegram was revealed, the fact that it had been transmitted unknowingly by the State Department was omitted.

Tuchman argues that the German were determined to win the war because to settle or lose would mean a revolt that would lead to a regime change and Kaiser would be gone. They were right…

The book has many marvelous turns of the phrase, and enough skulduggery for several Le Carré novels. Spies and counter spies tripping over each other.

A few quibbles. A lot of guesses are passed off as fact, e.g., ‘when he read the telegram, his heartbeat faster..’ ‘When the Kaiser again ….., he felt his grasp on reality slipping away.’ How can she possibly know the inner mind of all these characters. Of course, it adds a human touch to offer these comments and makes it read like a novel, but …. it is sheer speculation. She could have said ‘he might have felt his grasping reality’ or ‘his must have beat faster’ but these subjunctive constructions reveal the description as hypothesis not as fact. Just in case she was paraphrasing a source I checked the notes three or four times and found nothing to support the text.

She also more than once reifies a nation, ‘Germany reacted.., rather than which Germans or ‘the State Department was embarrassed when..,’ rather who was embarrassed.

She underestimates William Jennings Bryan and disparages him as though she had recently seen the play ‘Inherit the Wind‘ (1955). He was certainly the most well travelled man in Wilson’s cabinet and he read German and his wife spoke French on their travels. I have no doubt that he would have blunted the pervasive and pernicious influence of Colonel House in the State Department.

She makes no mention of that superstar journalist of the day H L Mencken who was pro-German. Yet he made enough noise for six others.

I was keen to read this as a precursor to her great book The Guns of August (1962), and also because I found that the Zimmerman Telegram was hardly mentioned in the biography of President Wilson I read, yet I recalled it to be of great importance.

If Woodrow Wilson had lost the 1916 election

Hypotheticals are often very entertaining, and sometimes, though rarely, informative.

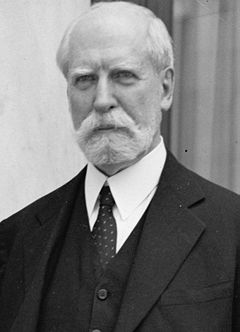

Woodrow Wilson concluded in October 1916 that he would lose his bid for re-election in November against Charles Evans Hughes, the Republican nominee. As a constitutional specialist Wilson had always deplored the hiatus between the early November election and the inauguration of the new president in March of the following year. During that three month period — the lame duck period — the incumbent had no legitimate authority though the formal powers remain.

Charles Evans Hughes

In 1916 the lame duck would be no laughing matter with submarine warfare a weekly occurrence off the Atlantic coast of the United States and Europe burning in an endless war on a gigantic scale while Japan sharpened swords in the Far East and eyed Mexico. In that situation Wilson had no wish to exercise the formal powers shorn of a popular mandate. Moreover, he thought the people’s choice should take on the responsibility immediately.

He made a secret plan to accomplish that end while staying within the Constitution. Here is how he proposed to do it. As soon as it was official that Hughes had won, he would dismiss the Secretary of State, Robert Lansing. Wilson would then appoint Hughes to be Secretary of State. While Congress is not sitting the President can make acting cabinet appointments like this as a temporary expedient until Congress reconvenes. Once Hughes accepted the appointment, Wilson would ask his obliging and unambitious Vice-President Thomas Marshall to resign. Without a doubt Marshall would have readily complied. (Lansing would have almost certainly resisted but he served at Wilson’s pleasure and at the end of the day would have had no choice but to stand aside, willing or unwilling.)

With the way then clear, Wilson would himself resign, and by the existing line of presidential succession the baton would pass, absent a Vice-President, to the Secretary of State, Charles Evans Hughes who would also be President-Elect. Wilson’s supposed that this could be done within three days or even less once the election results were known. Hughes had only to travel from New York to Washington and say ‘Yes.’ Of course, Wilson hoped against hope to win, so he put the plan which he had typed himself in a desk drawer and waited.

On election day the result was close, and in 1916 reporting results was slow and sometimes uncertain since journalists sometimes jumped the gun. (No comment.)

It seemed by late evening on the East coast that Hughes had won. Hughes went to bed believing he had been elected President of the United States. But he woke up to find that California had voted for Wilson and the left coast was enough to keep Wilson in office. The secret plan went into the locked filing cabinet of history. Would a president today think so hard about the best interests of the country and be prepared to concede to an opponent to serve that interest?

In 1933 the XXth Amendment to the United States Constitution reduced the gap between the election and inauguration from early November to January and re-routed the Presidential succession, after the Vice-President, through the presiding officers of the House of Representatives and the Senate before going to the Secretary of State.

There are two competing principals. The first is that a successor should be someone aligned with the president and au fait with current developments in the executive, hence the Secretary of State as the most important cabinet office should be third in line. That principal applied until 1933, despite Secretary of State Alexander Haig’s remark when President Reagan was shot in 1981.

The second principal is that the successor should be an elected official with broad responsibilities, hence the presiding officers of the legislatures. While not members of the executive, they are engaged with the daily processes of government.

Eight of 44 presidents have died in office. In each case the successor was the VIce-President.

By the way, Hughes had a long and varied career in public service: Governor of New York, Associate Justice of the US Supreme Court, Secretary of State, Justice on the International Court of Justice, and Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court.

Ben Oxlade, Death in Brunswick

Recommended for the Melbournoisie out there. But they have all probably read it. Not a krimie, worse luck.

A two-hour diversion into the drug addled mind of ole whashisname, Cookie, Carl the cook, or is that Charles. Sometimes not even he is sure.

Cruel but insightful and amusing caricatures of the feminist wife, the Irish mother, the Greek club owner…..and Carl himself.

His movie review fits most of the trash on the wide screen today: deafening, gory, brain deadening, blinding… Get the result same from a finger in a power outlet!

‘They went into the theatre. it was a maelstrom of noise. The film had started….. The screen was awash with meaningless images and the soundtrack was a … frightening roar…. Creatures from his worst alcoholic nightmare, groped and slithered across the screen.’ That’s entertainment! That describes ‘Star Trek: Into the Darkness’ very well.

Quite fitting that Shane Mahoney wrote the intro. They have the same ink in their veins. Though Mahoney’s effort to compare this book to Thomas Mann’s ‘Death in Venice’ falls flat.

A google search does not return any other novels from Oxlade. A one book writer and even that book is now overshadowed by the movie in the publisher’s blurb on the back of the book has more enthusiasm for the film than the book.