Roberto Calasso, The Art of the Publisher (2015).

GoodReads meta-data is 148 pages rated 3.78 by 608 litizens.

Genre: Memoir.

DNA: Bibliomania.

Verdict: Engaging.

Tagline: Indophile.

Roberto Calasso is himself a story teller with many books to his credit, however he is also a publisher of books by others. Between these covers he has collected essays reflecting on his long career as a publisher, a vocation that combines a circus ringmaster with a bazaar stall holder on his telling. After an apprenticeship in other publishing houses, in the 1960s he started Adelphi to bring to Italy high quality works the big publishers, for reasons of their own, were not translating or publishing, e.g., George Simenon’s novels, apart from the Maigret titles.

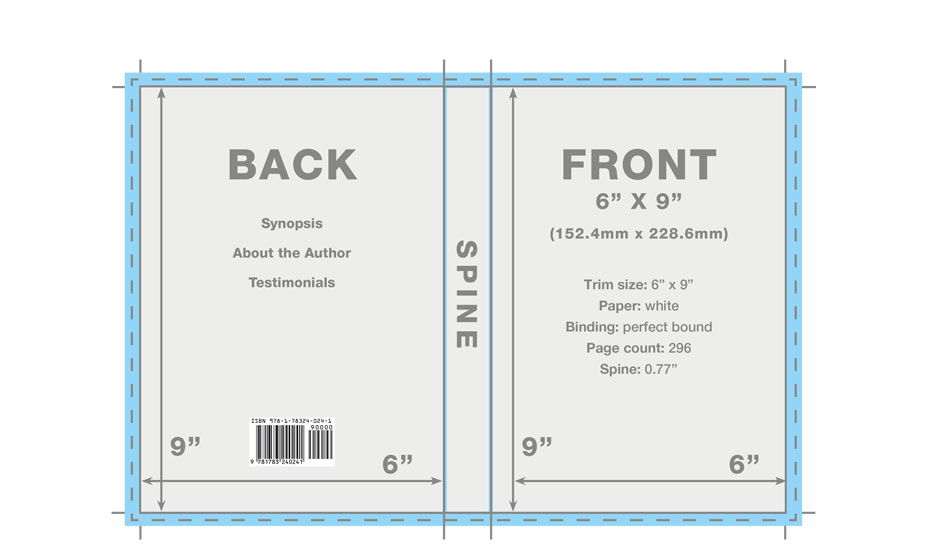

To establish Adelphi press, Calasso strove to make an Adelphi book whole, by that he means making every aspect of each book from the cover, to the blurb, to the advertising, the front and back flaps, the paper on which it was printed, the font, the spine to be all of a piece with the words of the book itself.

He also broke with a long tradition in Italian publishing, he says, of treating readers as children. Before Adelphi, foreign books in translation for Italian readers always had a forward explaining the book to readers. Adelphi omitted such condescending expositions. Indeed, in one case when translators admitted they could not render a certain German writer into serviceable Italian, he published the book in its original German in the Adelphi collection for the Italian market. Was that the incomprehensible Heidegger?

Few readers like me spare a thought to publishers, but perhaps we should especially in this age of transition from analogue on paper to digital in pixels. He dissects one passionate defence of digital books in a series of brilliant strokes. The expositor went on and on about how digital books mean we read together as a community because we can know who else is reading this book, how far they have gotten, and the very passages which they have underlined and the annotations they have entered. This approach undermines the very essence of reading, per Calasso, namely a silent and solitary communion between author and reader, not among readers, not with crowd noise, alone and yet in company. Amen, Brother Roberto. Willa Cather said the meaning of a book is a chemical suspension in the air between reader and page. John Williams in Stoner (2006) has a moving passage on this communion at the end of this neglected masterpiece.

Digression warning: Speaking of underlining or highlighting texts, as a student I bought used textbooks. The crush and confusion of the beginning of semester in the bookstore taught me how to select quickly from the used copies. One that had many passages underlined in the first chapter or two, was a prospect. The more underlining in those chapters the better, because it meant the underliner had no idea what was important, using a net when a line was needed. Invariably in later chapters there was no underlining because the over-underliner (I couldn’t resist that) had dropped the course and sold back the book. Every time I applied this algorithm, it worked: a heavily marked up first chapter meant clean pages to come. Detour is complete.

Does a reader of William Faulkner’s Sound and Fury really want to see what everyone else, or even a selection of them, have underlined while reading this demanding but memorable story? Does it add anything to our relationship to the bewildered Benjy?

Moreover, I harbour the suspicion that in the whole world every line of every book has been underlined by someone, and so…. Yes, what is the point? Good question, Mortimer.

In Calasso’s essays there is much insider talk of Italian authors, editors, publishers, translators that would mean more to someone versed in Italian Twentieth Century literature than it does to me. But Calasso has some perfect turns of the phrase to hold even my jaded attention.

The tagline ‘Indophile’ above comes from his repeated references to Indian mystics, the Hindu vedas, which did not make much headway for me. It comes across as faint echo of tie-dying, dope smoking, incense burning Westerners who went to India to find the perfect curry.