IMDb metadata: 1 hour and 46 minutes rated 4.9/10 from 5730 raters.

A big budget disaster movie from the era of big budget disaster movies. The clichés are all there: the solitary Chicken Little, the fetching femme, the stalwart buddy, the doubting Thomases, the extras to become victims, the special effects of falling bricks and rising waters. But it does have some twists that set it slightly apart.

The set up is this: A large object is on a collision course with Earth! Only James Bond, once again, can save the world. With half-hearted grousing he is summoned for reasons that never become clear since he does nothing thereafter but snipe at others. President Henry Fonda mouths lines. Trevor Howard has a few moments to impart some purpose.

The twist is that to destroy the Really Big Space Rock will take the combined effort of the USA and the USSR. Much mutual suspicion is exercised, but in the end the Soviets agree and trust the mission, controlling fourteen USSR nuclear warheads to one scientist and a translator, whom they send to New York City. Sure. That is the way the Kremlin worked in 1979. The Russians are coming.

The scientist is the redoubtable Brian Keith who does it well, and his translator is a very drawn Natalie Wood, who adds grace to anything.

The scientist is the redoubtable Brian Keith who does it well, and his translator is a very drawn Natalie Wood, who adds grace to anything.

The USAF in the person of Martin Landau opposes everything with childish temper tantrums. Salute that! Don’t blame Marty because he is written that way.

Together the Russkies and the Yankees blast the rock but shards still strike Earth giving us some nice disaster scenes. Yuk. Bond saves everyone.

By the time this one was made the disaster tire had no tread left on it. All the tropes are there but everyone from the scriptwriter to the extras seems bored by it. Karl Malden puts the most into his part, and Keith seems to enjoy the language barrier, but Bond and the ethereal Wood seem to be waiting for it to end. So did I.

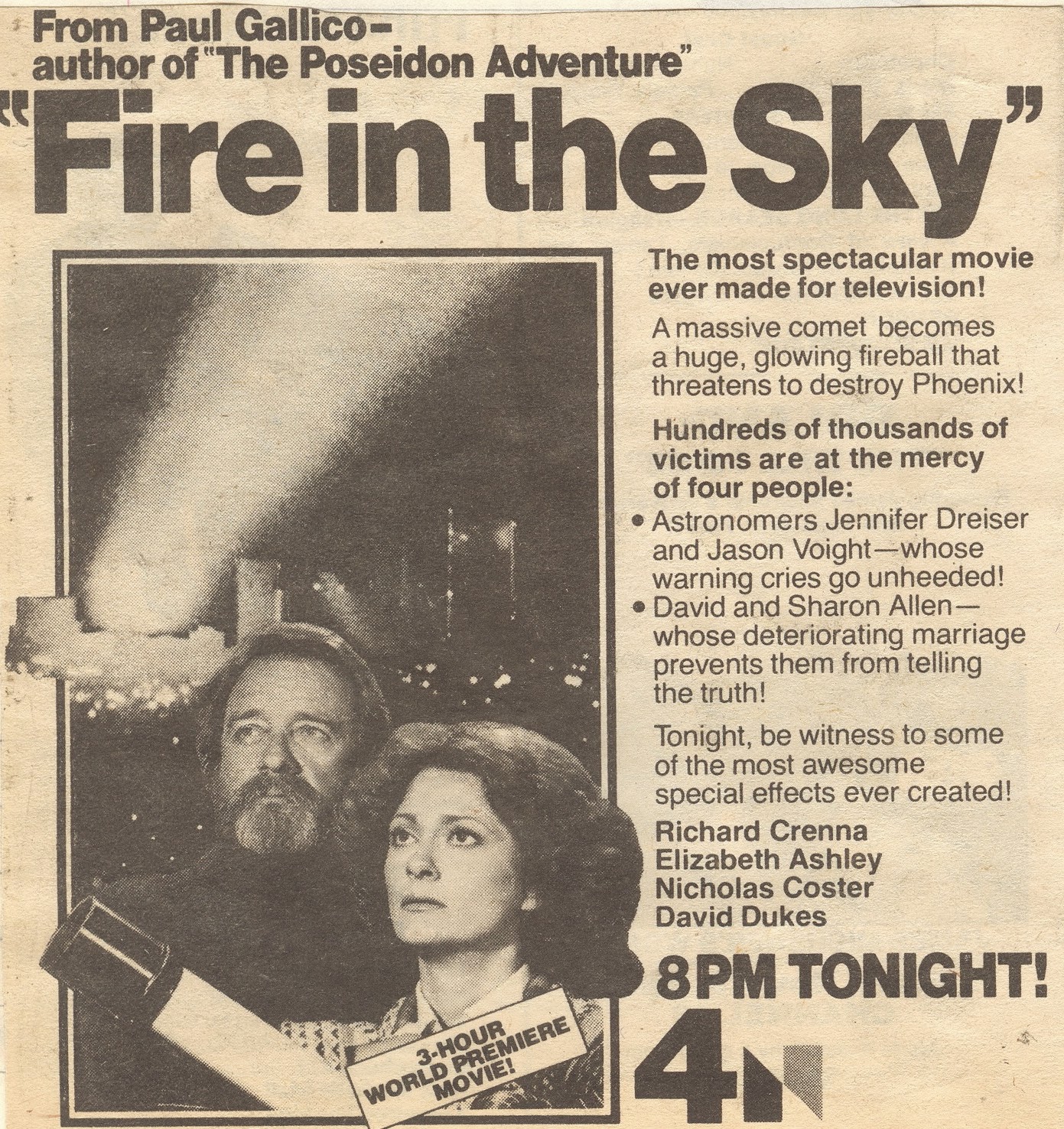

Richard Crenna in ‘A Fire in the Sky’ (1978), reviewed elsewhere on this blog, did the same part as Sean Connery in this film, and Crenna did it better – more energy, more intelligence, more conviction, and he had material that had some science and some compassion in it. This film seems to rest entirely on the big names in the cast, and they in turn go through the motions as quickly as possible.

The rockets in space was a neat idea and well presented for the toy model special effects used.

This block buster was delayed in production in the effort to improve it. Failed. The ‘New York Times’ reviewer, Jane Maslin, nailed it: slow, sludge, half-baked, boring. Those were her kindest remarks.

Category: Film Review

‘A Fire in the Sky’ (1978)

IMDb metadata: 180 minutes @ 6.6/10 from 333 raters

The scientists agree a meteor is headed for Phoenix! Whoops! The scientists do not agree! Is it a meteor or comet? Will it hit Earth or pass by? If it hits where? If it passes by, then how close? How big is it anyway? There is disagreement among the boffins on each and every point.

In a roomful of PhDs all the KPI career incentives reward disagreement, even at the end of the world. The bickering, logic chopping, semantics emerge to mask the egotism, opportunism, and careerism. Seminar normal.

The local political decision makers decide the financial disruption of an alert is too great. This decision is partly based on the belief a panic would ensue with loss of life, destruction of property, and worse, the arrival of Fox News. They are also sure that there they do not have the infrastructure of shelters or trained personnel to do anything constructive. No one wants to pay taxes for comet shelters.

Journalists, of course, know better and strive to tell all without regard to consequences! Situation normal. They tell all and panic ensues with the loss of life which in journalism logic is vindication.

In Arizona the gubernatorial response remains guarded and equivocal. After all only one scientist is doing Chicken Little. Why is he right and everyone else wrong? Because the script says so, that’s why!

Meanwhile, the USAF applies the usual foreign policy response: blow it up. But the rocket misses. Whoops! So much for that.

The script includes a lot of science, including a distinction between a comet, asteroid, and a meteor. Despite the summaries and reviews on the net, in fact, the political decision making is shown to be careful and sensible. At first the Air Force general is reluctant to go the expense of a missile launch on the say-so of one scientist, but in the end there is a pre-emptive rocket fired and it is a miss, a near miss, but a miss. But the screenplay also includes far too many sidebars that blur the focus. Merlin Olsen is a treat but out of place. Ditto the thwarted young lovers.

Andrew Duggan imparts dignity to the proceedings as President. Governor Dukes lays out the complexity of the social consequences. But Richard Crenna carries the film with integrity and conviction. Particularly striking was his effort to frighten the child as a way of showing the parents what the reality of the situation was likely to be. That was surprising and effective, and done with conviction. He learned a lot from ‘Our Miss Brooks.’

The direction is leaden but perhaps that is because the material was stretched to 180 minutes! Had it been halved the pace would have been better.

The 1970s fashions are much in evidence, aviator glasses, wide neckties, hirsute faces with flared trousers, altogether enough to put off any time traveller.

The original plan was to air it on television after the theatrical release of the big budget ‘Meteor’ (1979) to ride its publicity coat tails. (Its IMDb score is 4.9.) But with the big budget went big egos and that production languished and in fact ‘A Fire in the Sky’ went to air first. Best laid plans and all that.

‘Robinson Crusoe on Mars’ (1964)

IMDb metadata: run time 1 hour and 50 minutes rated at 6.6/10 from 5206 raters.

A tale of survival on the Red Planet told in a semi-documentary fashion.

Mars Gravity Probe 1 from the United States Air Force orbits Mars gathering data for subsequent surface missions: lights blink, levers click, wheels turn. The MGP1 has a crew of two and half. Half? There is Batman, Survivor, and … Monkey, part mascot and part scientific subject, but mostly comic relief. Ah huh.

Round and round they go in a low Mars orbit, until the script writer’s old friend, a meteor arrives to spoil the ride. They have to put the pedal to the metal to get out of the way. The budget cutters made sure the fuel was adequate with no reserve, so the MGP1 is now out of gas in a decaying orbit. Time to leave. They eject. Nice effects.

Batman cacks it on impact, but the monkey survives. Survivor also survives and the next forty-five minutes documents his determined efforts to find shelter, air, and water, which he does with the help of Scouting manual and the monkey. He records it all on his enormous iPhone for Watney in ‘The Martian’ (2015), reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

Mars is colourful and has all the survival-conveniences an astronaut could want. It reminded the fraternity brothers a lot of Arizona. It is also empty. Survivor hallucinates now and again. But he puts his training to good use. Blah, blah, blah.

Then company comes. Remember crossed telephone lines in rainy weather courtesy of Telecom? This movie gets crossed with ‘War of the Worlds’ (1953) and its Martian spaceships appear zipping and zapping. Well, it is their planet, after all.

Someone should have yelled ‘Cut!’ and sent them to the right studio. But no, they are part of this story, too, working overtime.

It all seemed random to me, but Survivor concludes they are ‘interplanetary spaceships’ (psst, we know better, they are Martians) mining ores from Mars using slave labour with wardrobe by Pharaoh.

Survivor lies low but an escaped slave tumbles into his arms. They flee and in time bond, helping and saving each other from the perils of the pursuit of the mining zipper zappers, stumbling around the set, and enduring the monkey’s scene stealing. Survivor is left no choice by the screenplay and he calls this man Friday.

The miners search for Friday with more zipping and zapping repeated ad nauseam. The two of them make it to the polar ice cap for some reason. Maybe the miners are afraid of the cold. Shirtless Survivor finds it cold. Geez. The clock ticks. How will it end? ‘Soon!’ cried the fraternity brothers. A rescue mission from Houston arrives to collect them. What will become of Gypo? Where are the zipper zappers? How will the rescuers land and take off? These are some of the known unknowns to ask Donald Rumsfeld about the next time I see him on a crosswalk in DC.

Daniel DeFoe’s novel ‘Robinson Crusoe’ (1719) had themes of colonialism, racism, humanism, equality, fraternity, and more. Living with the noble savage Friday, DeFoe’s Crusoe comes to re-evaluate the norms and conventions of his society, and in so doing he himself changed. All of these themes are washed out of this rendering, leaving a documentary of Hollywood survival. Survivor spends a lot of time shirtless, sunbathing on Mars, Friday looks like he left a pyramid building site, and those cut-outs from ‘War of the Worlds’ do not fit.

Taking the air on Mars.

Taking the air on Mars.

Survivor was Paul Mantee, an anonymous toiler in Telly-wood, cast precisely because he was unknown, and he stayed that way. This was his only starring role, and without a woman in sight, but, well, the monkey is called Mona. (Sniggering was heard from the fraternity brothers.) A cast of three and half is it. Batman has only two scenes, but the second, the dream sequences is very well done, with the blank face and dead eyes he anticipated his Batman.

In short, it lacks just about everything a feature film of the 1960s had to have, yet it runs for nearly two hours when the norm was 90 minutes for everything but a blockbuster with a giant cast of well known stars. I saw it on release, I seem to remember, but it left no impression. (Maybe it was date night.) Nor does it now.

‘Dumkirk’ (2017)

IMDb metadata: 1 Hour and 47 minutes. 8.1/10 @ 312,875 Opinionators

How could such a tired, clichėd, and disjointed movie be made of this event? That it ranks highly as shown above only indicates the audience. I put off watching it knowing I would find the historical inaccuracies a pain. Right again.

Why do the inaccuracies matter anyway? Isn’t it just a movie? Afraid not.

I have heard far too many people refer to movies for historical facts. None of the half a dozen reviews I read after watching it made any reference to historical reality. Yet many viewers, most viewers will take it just that way.

In short, both John Mills in ‘Dunkirk’ (1958) and Jean Paul Belmondo in ‘Week-end à Zuydcoote’ (1964) had better material and played it better.

What’s to like? It makes a short list.

It just starts. Bang. No information card. No voiceover. That makes it a fast and clean start. Good, let the ride begin.

The cinematography steals the show, especially in aerial scenes, and I am sucker for that. The best I have seen since ‘The Dark Blue World’ (2001) and before that ‘Piece of Cake’ (1988).

Some of the acting is up to the ‘Mrs Miniver’ (1942) standard, notably on the small boat, but most isn’t.

There is a high blood pressure soundtrack which too often competes with the screen. A mute button was needed for that. If the visceral reality is the point, then let’s hear that as the men did.

I also like that it is feature length and not an epic of endurance for the viewer!

What’s not to like is a longer list.

Overall we get nothing about the human side of it, the decision-making, Belgian, English, French, or German. Without that, it becomes a disaster movie where an uncontrollable force of nature erupts and a mix of individuals try to survive. It could have been played without a word of dialogue and that might have improved it.

This impression grows because we never see a German until a few shadows in the last scene. The unseen enemy becomes a malevolent storm, not other fallible human beings.

Likewise most of the characters are nameless ciphers. Though, curiously, some of the nameless are named in the credits. Confusing or confused? Pick one!

By default the movie also makes the evacuation seem disorganised but in fact the staff work to organise and plan was extensive and that is largely why it was as successful as it was. I have mentioned this is another post on this blog. The essential point is that it was ten, that is, 10 x, more successful than early estimates, most importantly including those made by the Germans.

Here are a few IS, that is, Irritating Specifics.

At the beginning, the five Brits amble down the street; they are too clean. They dawdle. There is no urgency. After at least five weeks in the field they are clean. Ah huh. They might have 2018 fashionably long hair after weeks in the field but they would also be unshaven and dirty with torn and soiled uniforms. This impression is not mitigated by a few close ups of dirty hands. Nor would they amble at this juncture. They dawdle for no other reason than to have the idyl broken by gun fire. Very staged and it is obvious.

The town of Dunkirk is shown tidy in the film when in fact it was rubble by the time the BEF got there. ‘BEF?’ That is, the British Expeditionary Force, as it was called.

The reality.

The reality.

Dunkirk was held to anchor the flank and it was devastated, a ruin, not a ghost town as presented here. This is an important point because the French did fight hard in the North, particularly around nearby Lille which was also flattened. The defence of Lille delayed the German advance in the North making the evacuation possible.

The mountain of sandbags is impressive and pointless. Who had the time to build it? And why bother? Manned by only three poilus, who are not even going to slow up a German patrol. Nor is it likely they would know about the evacuation. Master plans from London are seldom passed onto to isolated French riflemen like the uncredited Daniel Auteil. Moreover, more than 100,000 French were evacuated, some in French ships usually omitted from English telling of this story, though some of the ships we see in this film with British flags are French. Confusing, non?

Branagh does a lot of posing and takes off his hat for no other reason than the look. Who he is and what he is doing, apart from posing, is left to guesswork.

Why does the loaded hospital ship stay on the pier long after it is declared full? By the way it clearly was not full.

This ship is full, not.

This ship is full, not.

This ship is full.

This ship is full.

Indeed the crowd in this film was often sparse. Except for a few scenes there were not many extras. The whole cast might has well have been CGIs given how little humanity is allowed to them.

While on matters nautical the destroyers do not seem to have anti-aircraft Bofors guns but the I-class ships did and they were the ones there.

The men who take refuge on the beached Dutch trawler make a sitting target for a Stuka bomb attack. Surely they would have known that. Nor do they take the simple precaution of posting a sentry. Why someone getting off would plug the holes in the hull is anyone’s guess. Yes, I know stress does bend the mind, but it does not enlist sympathy.

The choreographed cheering looks just like that. The news does not travel down the line but erupts all at once, clearly on cue. Moreover, most men on the beach were hiding in the dunes out of sight to avoid being targets for air attack until ships were available so they would not have seen much.

Nor did Branah have to wait for the French as the Irishman says in closing, because after the first day Churchill, unseen in this telling, ordered first come first served and about 100,000 French and Belgians were lifted to continue the war.

The aerial choreography was grand but full of inaccuracies. The Messerschmidts did not have yellow nose cones to make them easy to identify. The Spitefire carried ammunition for one 20-second burst, or divisions thereof. To hit anything they had to close to one hundred yards or less so that the target filled the target ring. This Spitefire has nearly forty minutes of ammunition. Moreover, after all the early fuss about fuel, the last one has a bottomless tank. Nor does the Spitefire have the endless glide path shown. With the engine, weapons, and pilot in the front, it was front heavy.

Yes, the Tommies on the beach did decry the lack of air cover but surely they would not have said ‘airforce,’ but RAF. Was it a marketing decision to script it as ‘air force’ in case some viewers did not know what RAF is? The RAF did want to preserve assets for the next round until Churchill overrode it. The limitation was distance and also guessing when the Luftwaffe would be there to attack.

The Luftwaffe did not have to go out in the Channel to engage the RAF. Why do so? The RAF attacks were limited by range and were as unpredicable as the German ones, while the beaches and waters were full of big targets.

Unlikely Heinkels were much used there but applied elsewhere to the main German drive, contrary to the myth, was miles away toward Paris with many stationery targets like railway yards, bridges, etc. For Heinkels to hit a moving ship with a bomb is a script writer’s dream.

The Channel is too shallow for U Boats and Dunkirk was a resort town because of the shallow waters which kept the destroyers out to sea but made loading small boats easy. Shallow water made submarines easy to spot from the air.

Of course, a Heinkel might have been there, ditto a U Boat. The point is the film is pastiche of incidents with no coherent story line. Looks like someone did a lot of reading and picked out of context a diversity of incidents for their cinematographic potential and then strung them together, not to convey what happened but to hop from one tableau to another and back. The result is a series of incoherent images without rhyme or reason. There is neither plot nor character. And as noted a couple of times above, the direction is stiff.

Yet no doubt some viewers will conclude that they know the history now.

It is heartening to see that some user reviews on IMDB are negative, despite the average rating. Unlike the professional critics who carefully avoid ruffling any feathers. I pine for a Pauline Kael destruction of this nonsense.

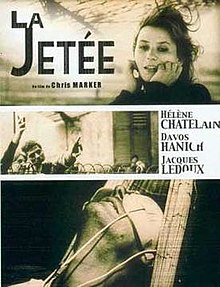

La Jetėe (1962)

IMDb metadata is 28 minutes of run time @ 8.2 from 23,848 raters.

A Sy Fy short that often appears on lists of great movies, and I can see why. It is arresting and mysterious.

It is after an atomic World War III and some think they have won but most have died. Survivors have dug into the Earth.

Paris is a burned cinder but deep down in the Châtelet metro station in the first arrondisement where six lines pass are the survivors. A lot of them. They have prisoners on whom they perform experiments.

One prisoner is selected and he prepares himself to meet a terrible fate with a mad and cruel scientist only to find a placid doctor who explains that they are trying to time travel either to the past to avert the catastrophe or to the future to get help. Some who have tried to travel through time have been driven nuts, others just died, not being strong enough for the emotional wrench and the mental effort.

The major prop is an eye mask with some wires inserted in it and a hypodermic. The rest is imagination!

The Man without a name submits and dreams or travels. No one is sure which it is. He, too, is unsure. The doctor is unsure. The viewer is unsure. the fraternity brothers dozed.

In the course of his backward travels he meets a woman to whom he tells his story and she listens, calm, attentive, interested. He keeps going back to her, though we learn nothing about her.

He also makes one forward trip and meets in a cloud of mist four individuals from the future with two franc coins stuck to their foreheads. They reject him but later relent and offer him personal sanctuary but they cannot help the others.

However by then he prefers the past with She who does not have a name.

In a dreamy sequence he goes to her at Orly aeroport on the observation deck, the pier, la jetėe of the title, and he is murdered by someone from the Châtelet metro station who is there with the other prop, the scary goggles optometrist use to calibrate lenses corrections.

He realises, as he dies, that he has seen this death, his own death, before. Huh. All very post-modern.

He dies. No one can escape fate is the moral, it seems.

There is an intermittent voiceover narrative that is laconic and cryptic. And all the film is still photographs, many striking ones of Paris in the spring and the gothic underground refuge evoking German expressionism. But all is done with a light hand.

At times in the silence, and there is a lot of that, there is a nearly inaudible whispering in German. Don’t know what to make of that. An echo from the past.

Mostly the palette is dark in that underground redoubt with many shadows in the black and white photography.

It has been reissued by Criterion and a poor quality print can be found on You Tube.

I have seen at least one repetition of that scene on la jetėe at Orly in a krimi with Alain Delon or Lino Ventura. Can’t pin it down. Orly was shiny, new, modern, and futuristic in 1962. Later it became shopworn and dilapitated, as when I made a pilgrim to it in 1980.

Marker was a photographer among other things and borrowed a video camera for one very short scene of a few minutes. Like others at the time nuclear war seemed inevitable to him.

He did other conventional documentary films, and what he called photoessays.

While he was a traveller to make the documentaries and friends with cinemaistas like Alain Renais, he shunned all publicity. No interviews.

Chris Marker

Chris Marker

Few photographs of himself. No official explanations of his work. Lived to 92. HIs last credit was in 2008.

‘The Martian’ (2015)

IMDb metadata: 2 hours and 24 minutes of life @ 8/10 from 597,255 zits

The most boring job at NASA in 2055? Monitoring the visual feeds from its Mars satellites. But someone does it and detects activity on Mars!

Backup a little for the set up. Ares I is NASA’s first crewed mission to land on Mars with four men and two women. They are at work on the Red Planet collecting samples. The combination of camera filters and sands with the desert in Jordan is well done in creating a Mars.

As they work, on cue a large and powerful sandstorm strikes before they can all get inside the ship. In the ensuing maelstrom, one of the crew, Watney, is struck by a flying rock and carried away into the murky darkness. Meanwhile, the rocket is so buffeted that it is in danger of tilting too far to the looney right for takeoff. It’s a do-or-die situation.

Commander, as she is called, pushed the button for blastoff, after suitable lip chewing. It is clear they could never find him in the storm and that the computer predictions of a catastrophic tilt are accurate. Willpower does not overcome the laws of physics, as it too often does in Hollywoodlandia. It is five against one to complete the mission.

Off they go on the six month return flight to Earth. What can go wrong?

Watney did not die. Through a combination of circumstances he survived the impact of the rock and the storm but he is now ‘Marooned’ (1969) on Maris. (Remember that one?)

Red Mars

Red Mars

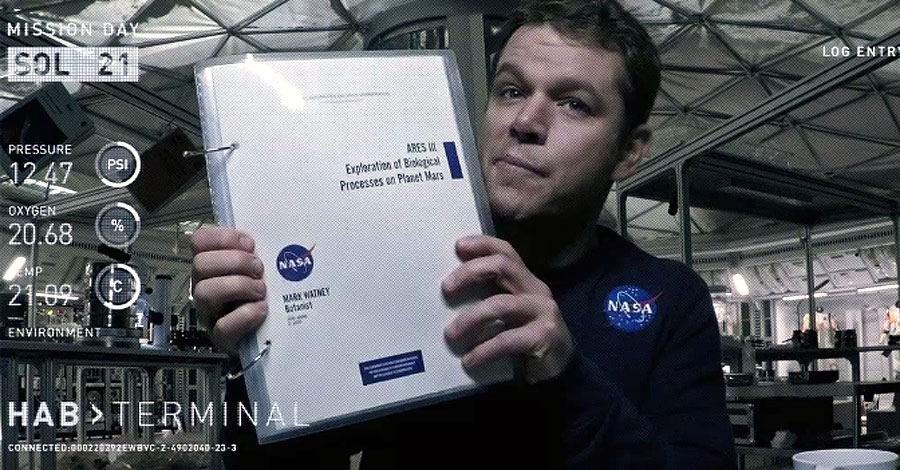

He becomes a ‘Robinson Crusoe on Mars’ (1964), remember that one, by first cleaning up his wounds and then setting about surviving with all the gear Ares I left behind.

Watney determines he will do science to survive. He uses his knowledge and sets about learning more as he goes. First air and water, then food. Then energy for the rovers and the Rube Goldberg mechanisms he engineers to meet his needs. It is not easy. Things go wrong. Mistakes are made, but he persists. Science is the way. Right down to burning a wooden cross left behind by a crewmate to make a fire. Banned in Alabama and Iran for that.

He survives by homework, not prayer.

He survives by homework, not prayer.

The storm destroyed communication so he cannot call home. Ares continues toward Earth. Watney does not know and does not ever seem to think the Mars satellites might spot him or his traces. He could have spelled SOS with the solar panels and saved us all a lot of time. On time see below. But his traces are spotted.

They watch his tracks as he manoeuvres solar panels and batteries. A lot of this. Too much.

NASA has thrown a lot of taxpayers money at Mars and left machines there from previous unmanned landings. Watney scavenges parts and material from the junk yard, including some communication devices.

Back at the ranch in Houston, Rubber Chin has to decide whether to tell the world Watney is alive and whether to tell the crew of Ares, some of whom are still chewing their lips. The decisions are complicated: nice scenes of hysterical journalists looking for a kill in a press conferences, and the political reactions related to funding some kind of rescue mission which may arrive too late anyway.

The two most interesting parts of that are the deux ex machina involvement of the Chinese space program in the planning and Richard Sharpe’s mutiny in leaking a hairbrained plan to the crew of Ares. By the rules of Hollywood, the hairbrained plan is the path of redemption which they must take.

Even more hairbrained schemes come into play to recover Watney. Glad wrap to the rescue. In ‘The Doomesday Machine’ (reviewed on this blog) it was aluminium foil.

Loved the emphasis on science and on teamwork and brainwork pace ‘Apollo 13’ (1995) to find solutions to one problem at a time. There are no histrionics. No he-man stuff and no resort to prayer to solve problems. Banned in another seven states and Syria.

Watney is well realised but not so Rubber Chin who has neither depth nor gravitas. Maybe I say that because in his efforts to look serious he reminds all too much of Al Gore whom I could never take seriously.

It is an ensemble piece and apart from these two, the screen time is distributed among the members of the group, many of whom are super nerds, as indicated by their ragged attire and evident poor personal hygiene. Keep those tired tropes coming!

Space flight, take off, link ups are marvellously presented, the gear has verisimilitude. No one smokes on Mars, unlike the 1950s visits to Mars by B-movie landers.

Again in contrast to that era, no big deal is made out of that the fact hat there are women on the crew or that the Commander is a woman. Even in the 1980s this was a theme screen writers had to use as a substitute for creativity.

Also mercifully absent were any magnified spiders much to the disappointment of the fraternity brothers.

Director Ridley Scott is the master of the medium.

Director Ridley Scott is the master of the medium.

It is an epic. — for the audience— to endure at two and half hours, and it could certainly have been cut to feature length. We don’t need to see everything when much of it is repeated in the video logs Watney makes and the ever present mini cams. Much of the footage seems to be there because we have it, not because the story needs it for the audience.

‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ (1951)

IMDb metadata: 1 Hour and 32 minutes. 7.8/10 from 68,694 discerning viewers.

‘Gort! Klaatu barada nikto.’ Repeat after me…… (and we pimpled youth did in case we ever ran into a Gort. We were ready!)

This was THE 1950s Sy Fy movie made with an A movie budget. Yet there was no creature in sight. But a very composed and dignified individual, Klaatu who made the mistake of trying to be rational in D.C. and got drilled for his trouble, twice over.

For the benighted, unenlightened ones, and included in this group all those who have seen the remake, the set up is this. One fine spring day a flying saucer finds a parking place on the Mall.

It is a sleek craft and there it is. Rush Limbaugh denies it exists. The Army tries to blow it up. Republicans vote to cut its appropriation. The media goes into a frenzy. Democrats try to mate with it, and the gawkers turn out in force to see blood. The circus is always in town in D.C. Scientists write papers on it to fatten the cvs. (Not the CVS drug stores.) Two days of tension follow until the alien emerges to proclaim peaceful intentions.

Obviously a Commie plot, so he is shot. Bang, problem solved, proclaims Rush.

Gort turns on his evil eye and atomises quite a few Red Shirts but then lapses inactive during an IOS update while Klaatu is carted off to a hospital.

When the alien comes around he is polite, correct, and rational. As such, no D.C. insider can understand him. ‘No, world leaders cannot be assembled to hear his message!’ Is the reply. ‘You are in our hands now,’ is the implication.

As if.

Klaatu commits an interstellar misdemeanour by stealing some perfectly fitting clothes and leaves the hospital. As usual the guards in this movie are always half-wits, relatives of the fraternity brothers.

Klaatu rents a room at Patrica Neal’s boarding house where he befriends her son Bob who becomes, unconsciously, his guide to the ways of humans. Cf. Carradine learning chess in ‘The Cosmic Man’ (1959). Seeing this refined, kindly stranger in the house, irritates Hugh Marlowe, Pat’s squeeze, she being a war widow. Hugh goes all passive-aggressive.

After a moving visit to the Lincoln Memorial, where Klaatu is impressed by the words of Abraham, Klaatu with Bob go to see Sam Einstein whom Klaatu helps with his arithmetic, and then reveals himself. He then arranges via Gort a selective but worldwide power blackout for thirty minutes starting at twelve noon Eastern Standard Time, just when he and Pat are alone in an elevator. He spills the beans to her, too. Now that he has started blurting it seems he cannot stop. The blackout was general but not complete in that aircraft in flight, hospitals, machinery supporting life continued to operate. We can hope it cut Rush off in mid diatribe.

Klaatu calls himself Carpenter. Get it? Smooth sailing to date, but Klaatu came out without his Amex card and he has to borrow bus fare from Bob in return for a pocketful of diamonds! Next thing you know, Hugh has sicced the army, police, navy, Rush Limbaugh, Girl Scouts, infielders, and the carrion of the media onto him. By the way, how did he pay the first weeks rent on the room in advance if he is busted?

Lock Martin wrapped in tin foil stands around, that is, Gort to the gormless.

The staging is simple and elegant almost documentary. Klaatu uses the flashlight on his iPhone one night to communicate with Gort. The interior of the ship is spare and yet intricate to the eye. Movement sensors turn light on and off, it seems. Mostly Klaatu listens and talks very politely, and correctly. With such good grammar and syntax, he must be an alien!

After Hugh has blown Klaatu’s cover, Klaatu and Pat scat, and in the ensuing chase the Rush posse kills Klaatu. Dead. So much for an alien taking a parking place on the Mall! That is a capital offence in the Capitol!

With his dying breath Klaatu sends Pat to Gort with that message. With the grit born of Kentucky coal country she does so, whereupon, as required by the film’s publicity department, Gort sweeps her up into his arms and carries her off to the spaceship, a helpless doll being carried by a creature was necessary for the advertising to communicate with the moronic members of the audience. That always works for the fraternity brothers. Gort then departs and recovers Klaatu’s body from the morgue by dissolving a wall and returns with it to the spaceship. There were only two guards, the third stooge, being absent, and Gort dissolved them, too.

We all know that left to her own devices Pat would not have gone all helpless and hurled herself onto a pile of folding chairs.

Neal’s face upon meeting the Twit in Chief.

Neal’s face upon meeting the Twit in Chief.

That was the doing of the writer and director. On her own she would gulped and got on with it without the histrionics.

Earlier Gort had incapacitated guards while two of them lounged with their backs to him, never alert, but now that Klaatu is dead, Gort is more extreme without Klaatu’s restraining hand, one infers.

While a stunned Pat watches, Gort lays Klaatu into an MRI which klatters and whistles him back to life. Resurrected. Get it.

Now robed in his shiny spaceman’s suit, Klaatu emerges from the ship with Pat, who scurries away, and Gort the Impacable. Note, the fraternity brothers cannot take a spaceman seriously unless in shiny pants. Klaatu’s turns to the assembled scientists Sam had gathered and some itchy fingered army types. Klaatu’s Address is this.

Blow yourselves up, if you wish. But the combination of rockets and atomic bombs makes Earth a threat to other planets. The League of Other Planets, LoOP, employs many Gorts to prevent such intrusions. Gort is merciless and all powerful. Cross him and he destroys the planet. Get it? No excuses. No extension. No sorry. No mercy.

Even pithier than Lincoln.

Off he goes: whooshka!

That message ignited ranks of successor films to explain why advanced aliens would bother with Terra.

Michael Rennie was cast precisely because he was unknown to Yankee audiences, so he would not trigger any residual expectations in viewers. He is austere and yet warm with the boy and so much more mysterious than the excitable and predictable Hugh. Though Hugh earned his Space Cadet stars in ‘The Earth versus the Flying Saucers’ (1956). Pat is a one-woman congregation who learns the lessons of peace and forebearance, or else, from the carpenter’s messenger, Get it?

Billy Gray is crucial to the presentation of character, but his part is not kid stuff. The is no ‘Tobor the Great’ with childish antics.

While the Army is portrayed as alert, organised, determined, and prepared, except for the sentries at the saucer who were careless, unbelievably stupid, and itchy fingered. The guards around the saucer are inattenive, how else could a giant in tin foil sneak up on them. The first response of the Army is to shoot. When the guards are alert it is to shoot. Slack in that only two grunts are left on guard, no more, and no officer to make decisions or with some phone numbers to duck responsibility.

Press hysteria in newspaper, radio, news reels, and television is there but in a minor key.

While Klaatu, as with every other alien visitor, wants to talk to the whole world, the Yankees will not hear of it. The conclave of scientists Sam gathers is international by the stereotypes of dress and appearance.

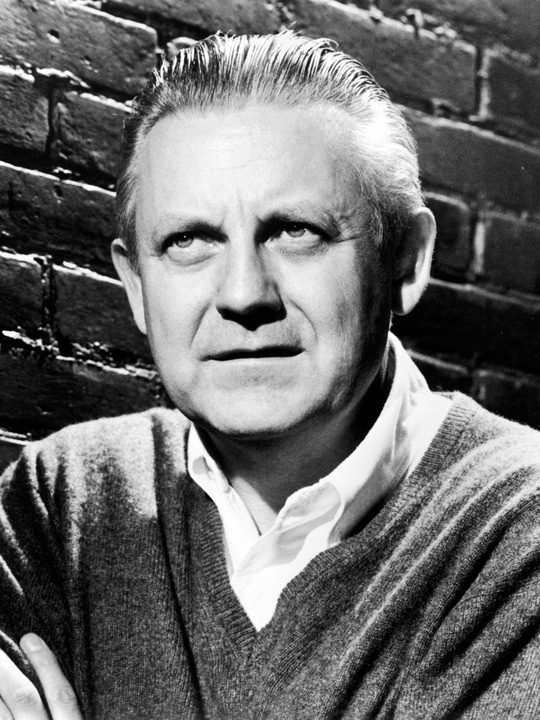

Robert Wise

Robert Wise

The director, Robert Wise made splendid films in many genres. His next Sy Fy was two decades later, ‘The Andromeda Strain’ (1971) and the first ‘Star Trek’ movie in 1979.

Pat reprised some of her role in a less dramatic account in ‘Stranger from Venus,’ reviewed elsewhere on this blog. To be enlightened find it.

The producer and director wanted to make a film about peace and cooperation during the Korean War and the evils of HUAC, a pre-Twit curse. To that end they rejected Spencer Tracy for the lead, thinking he would conjure up fatherly figures from his many other roles. They hired a brilliant musician for the score who cemented the theremin into Sy Fy. They risked offending Alabama with the temporary resurrection of Klaatu but put in a meaningless and distracting reference to ‘the almighty spirit’ to comfort the Alabamans who fear, rightly, that no one loves them. The producer insisted on employing the blacklisted Sam Einstein and not just for his electric hair. It would seven years before another producer would dare to employ him, such was the baleful influence of the junior Senator from Wisconsin whose name never crosses my keyboard. It took the decision and influence of the studio head, Daryl Zanuck to make all of the happen, and the risks for him were great but he ploughed ahead.

A second unit went to D.C. and filmed the Washington scenes, the actors worked in Hollywood and the editor brought them altogether in a seamless whole.

While it was stimulated by a Sy Fy story, the screenplay departs from and improves it immeasurably. It offers a more complex story with a larger cast of characters and a more fleshed out Klaatu. In this case the screenplay is superior to the story from which it is derived.

While channel surfing on a trip this popped up,and so I watched. Vaguely I had been putting it off until later, partly because it is not on You Tube and partly because I remember it very well,from previous viewings.

Disclosure statement. The reviewer has not seen ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ (2006) and has no wish to do so, because it will give priority to CGI over the simple story and will replace the detached calm of the original with a fevered attempt at action. So I assume. No doubt the time will come when curiosity will take me to it, but especially not immediately after seeing the original for fear of spoiling it with an unpleasant after taste.

‘Quatermass and the Pit’ (1958+)

IMDB metadata: 3 hours in six thirty-minute episodes, scored at 8.2 by 640 scorers. The plus sign (+) indicates it was shown in December 1958 and January 1959 on successive Friday nights.

Workers report finding human remains on a building site and a team of archeologists begin excavating the bones. Felix Leiter is a palaeontologist who leads the team and he needs publicity to delay the construction so that the remains can be carefully and fully removed in his own sweet time.

Meanwhile, Professor Quatermass is resisting attempts by the army to take over his missile experiments, but he is losing the ever so polite battle at the committee table.

Leiter calls a press conference and in the whirl runs into his old friend Prof Q. They compare troubles over brandy. The skulls are humanoid but not human. Are they the missing link, or that of the Twit in Chief?

Then the diggers come upon object, an object big enough and with the evident shape of a bomb, perhaps an unexploded bomb left over from the Little Blitz of V Rockets in1944. Down tools! In comes the UXB squad to do some more careful digging. Leiter fumes at being barred from his dig while the developer denounces the whole thing as a costly delay. By the end of the second episode anyone but a fool could see it is not a bomb, but Colonel Cardboard who has taken charge continues to insist, per the script, that it is German bomb. Unable to get his buddy James Bond, Leiter has called in Prof Q for moral support and together they do….research. This is not Indiana Jones country. This is thinking! Not punching.

They carbon date the remains and objects they find and they go to the library and archives to research the vicinity, Hob’s Lane. What do they find?

That the bones and skulls, though sort of humanoid, are five million years old. That makes them an odd fit for the chain of evolution as it was understood at the time outside Alabama, and for what it is worth, unlikely to be German. Not a single swastika was found. Moreover, they find that Hob’s Lane has a time-honoured reputation as a spooky place, with ghost stories going back to the Fourteenth Century and as recent as 1927 when the house adjacent to the building site was abandoned as unliveable because of…..’things.’ That got the attention of the fraternity brothers. ‘Things!’ They like things.

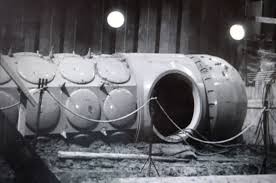

Meanwhile the Colonel has unearthed an object about the size and shape of a flying miniature submarine. There is much ill will between Colonel and Prof Q about what it is. They discover that it is not metal, as they know it. Nothing can penetrate it. Not an acetylene torch, not a diamond drill, not a split infinitive, not even the Twit in Chief’s ego. Colonel Cardboard’s solution is the soldier’s old friend, TNT. Prof Q goes all quivery and talks him out of it.

Finally, they find an open door on the other side of the gradually unearthed object and enter an empty vessel. The interior looks like a culvert, but the forward bulkhead is sealed off. Again they try to penetrate it with their penetrators. Then one after another a soldier and a safe cracker go spare while belabouring the bulkhead. Others will follow. Colonel is at a loss but cannot admit it. He puts it all down to a diet lacking moral fibre. Prof Q is turning his thoughts skyward. Leiter is counting his Loonies.

The unexploded bomb of Colonel Cardboard’s dreams.

The unexploded bomb of Colonel Cardboard’s dreams.

The bulkhead has pentagrams on it. Whoa! Is it time for the occult? Then, seemingly of its own accord, the bulkhead opens. Inside they find……gargoyles!

The ship was clearly divided into two parts, a large compartment for passengers — those humanoids — and the sealed bulkhead wherein were found three deceased gargoyles on loan from Quasimodo. Huh? Moreover after careful examination the craft itself has no mechanisms. One officer, not Colonel Cardboard, speculates that the ship itself must be a mechanism of some kind. What a brew!

Quatermass does what scientists do best, speculate. He fumbles slowly to this conclusion. The gargoyles came from Mars five million years ago before life was extinguished on Mars. What were they doing? They were scooping up some of our simian ancestors, taking them to Mars where the Martians altered the simians by some means (surgical or biological), and then returned them to Earth. This find was but one of many such missions to alter the population of Earth.The other missions were successful but this one was not. Why they went to this trouble is not clear. This Martian intervention explains the missing link in human evolution. God does indeed work in mysterious ways because Martian insects made us human beings. Does that writer have a sense of humour or what?

This program of genetic engineering by the gargoyles was observed through the millennia five million years ago, and they were remembered in images of devils, satan, and other creatures that were the reality on which the gargoyles were modelled. First superstition and then religion arose against the reality of Martian insects.

Prof with his favourite Martian.

Prof with his favourite Martian.

Meanwhile, Colonel Cardboard continues to yell about a German trick. Here the scriptwriter lets us down. Cardboard is so superficial it is impossible to take him seriously. But then the media begins to do what it does best, spread misinformation, panic, and hysteria. To hose it down, the Minister prefers the Colonel’s interpretation, and he makes sure he does not see for himself to keep his ability to deny reality in tact. That seems all to realistic.

Things go from stupid to disastrous when the minister decides, Colonel Cardboard being right, to hold a press conference on site and lay the whole story to rest as hoax. The energy of the crowd and the generators to power cameras, microphones, egos feeds the ship, which itself is some residual spectre, and things go flying.

Turns our Prof Q was right all along. It ends with his subsequent testimony laying out the story we have just seen.

It could not be made today. Bugs made humans. No God necessary.

There is much exposition across the episodes and each begins with a recapitulation of the story so far. It was re-made as ‘Five Million Years to Earth’ (1967). At feature length of 90 minutes this version compressed much with a faster pace.

It came from the fertile keyboard of Nigel Kneale, who has many noteworthy credits to his name, including the Quatermass franchise, ‘The Stone Tapes,’ and ‘The Year of the Sex Olympics.’

‘The Quatermass Xperiment’ (1955)

IMDB 1 Hour and 22 minutes @ 6.8/10 from 4295

On a mild autumn evening a young couple doing anatomical research in the long grass are disturbed by a rocket screaming overhead. It rattles the crockery and sets off the dog at a nearby farm. The eternal British Army Scotsman Gordon Jackson takes up arms to deal with the disturbance, but well none of his previous cinematic experiences has prepared him for rockets and it is his last scene above stairs. No, he doesn’t get zapped but calls in Professor Quatermass. Gordon went on to his next gig.

The QX was to send a three-man rocket into orbit and return it to Earth. While his rocket kit was home made, he has Lionel Jeffries from the Ministry ineffectually dogging his steps as he orders about everyone around with contradictory demands. Prof Q certainly likes being the boss!

After much dallying they pop the door and find one spaceman much the worse for wear. Where are the other two? Mysterious, indeed. Speculations follow.

Meanwhile, the Survivor, who gives a devastating performance, is rushed to a hospital for returned spacemen and guarded by a dolt. The spaceman’s wife decides a private hospital would be better but Prof Q wants to study the Survivor by bellowing at the nurses. Wife decides to spirit him away. This does not go well.

Now he is on the loose, wandering and wondering around. Some very nice scenes of his encounters. There is an inner struggle and the man is losing to the protoplasm. Oops, that is a spoiler!

As his humanity recedes, the protoplasm’s appetite increases. There goes the zoo. Gulp. At this point my imagination turned D.C. How long are zoo animals there safe from the GOP protoplasm?

The rest is a police procedural to track him, which has become an it, down. They do so in Westminster Cathdral. Well a mock up of it since they film company was denied access to the real thing. There they turn to the mad scientist’s old friend, electricity, to fry it. Success! Fried protoplasm is on the menu.

The intrusion into Westminister is cleverly done to juxtapose a bland high arts program on the building with this thriller. The former represents most BBC television at the time, fussy, erudite, recondite, arcane, dusty, in contrast to the whiz bang of Quatermass and his happy band of alien hunters.

Everyone is exhausted! Aghast! Relieved! Many sighs are heard. Wife is not consulted about any of this. Meanwhile, Professor Quatermass has learned his lesson and strides off to build a new protoplasm-proof rocket.

It seems this first rocket while in space passed through matter that entered the ship by magic and absorbed the crew. That is where the missing two went. Since this was a new cuisine, Proto proceeded slowly,and was only starting on the third when the ship under remote control from the ground crashed interrupting the anatomy lesson.

This story had aired in the BBC in 1953 in six parts to a great reception. That emboldened the entrepreneurs who would become Hammer Films to hire the author, Nigel Kneale, to re-write the story into a continuous film script, Kneale went on to write more Quatermass, so much it is hard to keep it straight. He also wrote one of the best things I have sever seen on the box, namely ‘The Stone Tapes’ (1972).

This film has the look of a quota quickie because the Yankee action man Brian Donleavy plays Prof Q, and does so with evident relish. Quota quickies are explained elsewhere on this blog. The essence is that they were cranked out to meet local content requirements but often had an American actor for marketing there. Most were as quickly forgotten, but not this one. It triggered more Quatermass films and encouraged Hammer Films down the genre path of Horror.

In 1955 an X-rating meant adults only, and Hammer accepted that readily by incorporating it in the title as was the case with some other films like ‘The Man from Planet X’ reviewed elsewhere on this blog. What children were then denied they can get today on video games.

‘Unearthly Stranger’ (1963)

IMDb metadata: 1 hour and 18 minutes, 6.6/10 @ 320 opinions

Funded from the tip jar at the tea room, the sets are bare, the effects ordinary, but the scene is well set and there is enough mystery to hold interest. Strangely, John Carradine is not in it.

It opens with a wide- and wild-eyed man in fear running down a dark and empty street. He looks back as if he is pursued. In a close up, John Neville is bathed in sweat. A paranoid atmosphere is established with a minimum of fuss. Neville ascends a circular staircase, working up more sweat, bursts into an office and starts a reel-to-reel tape recorder to tell the story in flashback.

Neville is a scientist in the Space Research Centre somewhere in Britain (where the streets are devoid of cars).

We learn in the flashback that he has just been promoted to the top job and that he has also just got married after a whirlwind romance in Switzerland. Is the conjunction of these two events a happy coincidence? Or has the script writer set it up? Guess!

The Space Research Centre consists of a receptionist, a large map of the moon on the wall, two offices, a chrome dome Philip Stone (who has been in everything), and Neville. His predecessor, whom we see ever so briefly, blew a brain gasket and died. Young, vigorous, and cheerful, yet he keeled over and the autopsy showed blood vessels shredded in his grey matter. Ouch.

Enter the rotund security officer,

Mother (as he was later to be in ‘The Avengers’), who tells Chrome Dome that a number of astro-scientists have blown brain gaskets in England, USA, and the USSR, though this latter report is suspect. Is looking at a large map of the moon the cause? What other explanation could there be, Erich?

Well, the fraternity brothers took a look at the wife. Ah ha! Turns out other brain-blown scientists also had new wives. Oh, ‘nocturnal over exertions may be the cause,’ they cried. Rotund does not even consider this obvious line of peeping.

Neville, eyes turned to the heavens, speculates that ‘they’ (hint) up there may not want us to get there.

However, attention now swings to Wife. It seems Neville knows nothing about her, ahem, apart from that, and it also seems, as he gradually realises, she took all the initiatives that led to the marriage. What he just assumed was his magnetism can be interpreted otherwise.

At times he seems to have suspicions of her, and at other times he is quick to defend her from Rotund’s insinuations. Neville is clearly in thrall to her. The fraternity brothers terminology is not suitable for a family blog like this.

But even the smitten Neville admits she has quirks. She sleeps with her eyes wide open all night. (Androids do this in other films.)

Okay. She has no pulse. Okay. (The fraternity brothers immediately spotted that as a trait of Venusians, per ‘Stranger from Venus’ [1954], reviewed elsewhere on this blog.) Moreover, she grabs a red hot casserole from the oven bare-handed with no ill effects. Later, the tears she cries burn her skin. What does all this add up to? See title above.

Aware of these oddities, Neville manages not to add them up. Nor does he connect the dots to his earlier speculations about what ‘they’ up there might not want. Thrall, indeed.

Wife gets misty at the sight of children. Hence the tears. Then when Neville cracks the formula for something crucial, who knows what, more tears come, because…. It is time to blow another brain gasket.

Spoiler.

She is indeed one of ‘they’ on a mission to stop the Space Research Centre from meeting its KPIs. In cinema-land few, if any other, aliens are women. What we get here is an alien who is conflicted, who has compassion, who has maternal instincts, as well as asbestos hands. This is a rarity in the Sy Fy genre. While some come in peace and do good works, no other alien to date falls in love and finds life on Earth good enough to stay. Wife does not want to hurt Neville, and she would like to have children.

Okay, okay. This is a pre-Liberated Woman who just wants to be a wife, homemaker, and mother, but in the context it is a volte-face. Of course, the fraternity brothers had a lot of questions, which are best omitted, about alien women.

When she wimps out of blowing up Neville’s brains, the receptionist steps in. Turns out for the last twelve years she has been erasing the blackboard every night, so that the scientists have had to start the formula over each day. This trick is called a Penelope among the Sisterhood. None of the big brain scientists have noticed this, not even the chrome dome boss.

However Chrome has figured how to overcome an alien. He grabs a sock from the laundry basket and the odour drives her to jump out of the window. Phew! Whew! Like Wife, she just vanishes. There today, gone today.

But there are plenty more aliens in the sea, since the last shot is of a group of women having a look. Gulp! Are they more of the Lunar Sisterhood? We’ll never know until the sequel.

No one smokes. Now that is odd in a piece from this period. No pipe fiddling. No cigars, No cigarettes.

Some reviewers call this an alien invasion film, but not so. there are aliens on Earth as agents of influence, but there is no invasion, nor a threat of one as long as the blackboard is kept clean over night. Brains are then safe.

The Cold War is there in the distrust of the Russkies, but the aliens are not a metaphor for them, or are they?