Sherlock Holmes has taken many forms over the centuries, none more compelling and engaging than in this eye-popper.

George C. Scott, at the height of his considerable powers, is Justin Playfair who had been an attorney of note and then a judge of discerning insight, striving always for justice in large and in small things. Striving always and never yielding, but the years passed and world seemed no more just and then his wife died. Lost of her compass, Justin shut himself away in the family mansion, for Justin has many dollars, and became….a reborn Sherlock Holmes, complete with period costume, laboratory, and (a poor) Brit accent. He secrets himself away in the house for months at a time in a waiting game with Professor Moriarty, who else, the nemesis.

Justin’s brother needs money and a lot of it soon to pay off a mobster, and sets in motion the wheels to have Justin committed to a mental asylum so that he, the brother, can take control of the dosh. He finds a compliant doctor who will sign anything for a dollar, and then needs a second expert’s signature. Enter none other than Dr Mildred Watson, played by that star of the Hollywood firmament, Joanne Woodward, a frumpy single woman with broken fingernails and an irritating manner.

Yes, Holmes has his Watson, at last! What follows is movie magic when movies still had magic.

Playfair as Holmes is a force of nature and intellect (‘I never guess!’). When she introduces herself as Dr Watson, Scott’s eyes pop off the screen; even on a DVD on a small television, he is electric.

Of course, he’s nuts, she can see that, but…. well, it takes time to be sure. He meets her, he because he wants a Watson, she because she wants a diagnosis that can be published to enhance her career. Both get more.

Scott’s march down the hall of the mental hospital is a delight to behold. Force of nature, indeed! (No spoiler. But Scott was a Marine for four years and it shows.) It gets better when, with his deductive powers, he diagnosis one of Watson’s patients far better than she has been able to do, working by the book.

It turns out someone is now out to get Scott, to settle the wayward brother’s debts, and the game is afoot.

The search for clues leads to a telephone exchange where a scene with a caller and an operator stayed in my mind for near fifty years. That is some credit to all the players, writers, and directors. When the operator turned, I knew what to expect. It was silent comment on enslavement of us all to the machine that is society, which Michel Foucault would recognize.

There is much more, but best of all is a scene and speech. which over the ensuing many years I have sometimes quoted and often recalled.

Seeking respite from the pursuing villains, Scott takes Watson to a theatre, an old broken down movie house; as they climb the stairs, she, querulous, asks ‘Why here?’ ‘Why … because they only show westerns here,’ says Scott as though naming the self-evident.

‘Huh!‘ is the learned doctor’s reply. Patiently, as to a slow-witted child, he explains why westerns are the ultimate expression of morality. It goes something like this: ‘If you look closely at Westerns you can see principles, the possibility of justice; you can see individuals who move their own lives, bringing them to the ends they deserve.’ There are no masses, no bureaucracies, no excuses. (Bring on Randolph Scott! I cried.)

There are false notes to be sure. Jack Gilford is wasted. The episode with the garden elves is pointless. The scenes of sidling are silly and without purpose. The plot is full of holes. If it is blackmail, no one seems to care. The march of acolytes at the end is fun but pointless, and the final descent in the end still seems…. confusing., incomplete, a let down. Writers sometimes just cannot figure out what to do at the end, maybe because they do not want it to end. I know, in this case, I did not either. A great trip with no arrival like ‘L’année dernière à Marienbad’ (1961).

It is a tribute to many hands that Joanne Woodward, that belle from Georgia by way of LSU in Baton Rouge, could be turned into this dowdy woman, she who melted the screen fours years later in ‘The Drowning Pool’ with that molasses accent and honey blond beauty. Here she looks exhausted and cranky or cranky and exhausted with a big city accent, and shambles around like a lame department store window mannequin. She has many other credits, of course, and I mention a few for the sheer pleasure of calling them to mind: ‘The Long Hot Summer’ (1958), ‘The Sound and the Fury’ (1959), ‘The Fugitive Kind’ (1960), ‘Paris Blues’ (1961), ‘A Fine Madness’ (1966), ‘Rachel, Rachel’ (1968), ‘Winning’ (1969), ‘The Effect of Gamma Rays’ (1972), the list goes on.

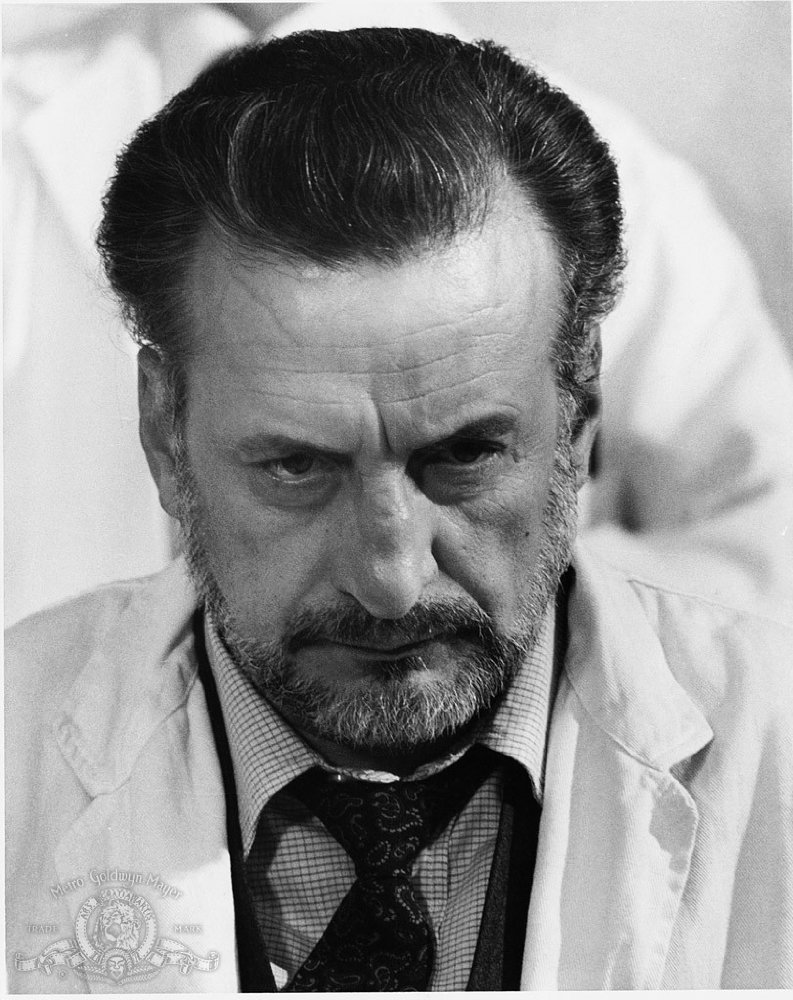

Scott, he too from the South — Virginia, was never better, and that is high praise. Among his remarkable performances was the prosecuting attorney in ‘Anatomy of a Murder’ (1959) who was so smart that he outsmarted himself, ‘The Hustler” (1961) as an avaricious agent, one of many crazed generals in ‘Dr Strangelove’ (1964), before taking the world by storm in ‘Patton’ (1970). He also did a noteworthy television series ‘East Side, West Side’ (1963-1964) as a social worker in the bowels of New York City. He had the reputation for professional intensity that sometimes put off other actors. Once he was in-character, he stayed there for the duration. Though not trained as a method actor, he out-methoded most of them.

That intensity shows in another role.

That intensity shows in another role.

The IMDB entry is sketchy with only first names for the characters, and not all of them. It has a rating of 7.0 which is respectable but not high enough.

I saw ‘They Might be Giants’ on the wide screen in Edmonton Alberta Canada when a callow graduate student and a night at the movies was a major financial commitment. It was memorable and I have checked many times in the following decades to see it again. No luck. Then a few weeks ago I happened to check again and lo, there it was on the Amazon site. I ordered it and when it arrived, I ripped it open and watched it, a rare treat that has withstood the test of time.

Category: Film Review

‘A Night at the Opera’ (1935)

It was a morning on the Sydney Opera House Quay at the Dendy Cinema Theatre where Jim Kitay and I went to see the antics of the Marx Brothers, Julius, Leonard, and Arthur, and so on. Neither Karl, Milton, nor Herbert are in this one.

It is feature length at 93 minutes, cut from the original release of 98 minutes, and it is a big production, i.e., a large cast, and some set-pieces worthy of Busby Berkeley. Old troupers like Margaret Dumont and Sig Ruman liven things up. The screen play is by that stalwart of the typewriter, George Kaufman. It is scored at 8.1 on the IMDB. That is impressive.

Among the outstanding scenes are the crowded stateroom on the steamship and the aerial acrobatics in the theatre. There is also a good deal of ‘Il Trovatore’ sung by Kitty Carlisle and Allan Jones. Ms Carlisle continued to sing well into her 90s, says the fount Wikipedia.

Otis B. Driftwood, now there is name with which to conjure, reminds me of some scholars I have known. Always on the prowl for easy takings and completely irresponsible.

These things are best seen on the wide screen without distractions, but if that is not an option, turn the lights down and cue it up on the idiot box. These idiots always have something to offer.

‘Willa Cather: The Road is All’ (90 minutes) (2005)

While marvelling once again at Willa Cather’s life and work in Red Cloud recently, we acquired this video as an aide-memoir. It is as wonderful as the woman herself. There is a very intelligent narration delivered with grace by David Strathairn, punctuated with interviews from critics and scholars.

While most of the talking head spouted the professional cant, a few seemed to be so emotionally attuned to Cather that they spoke in plain English with a catch in the voice. Those are the capital ‘R’ readers to this reader.

The sayers of cant are the sayers of cant, and their careers will flourish as they impress each other, but they have nothing to say to a reader.

Someone who hesitates to speak, who pauses to think, who slowly finds the right words within, and then says them slowly in simple declarative sentences without the blot of jargon, these people I want to hear. The video had several of these Readers.

More important are the readings from passages of her novels through her life as she explored new themes and ideas, but always returned to Red Cloud for inspiration from her formative observations and interpretations.

How a fourteen year old girl could fathom death, as she did, and revert to it more than once, is one of things that makes me think that Willa Cather and her kind are aliens, come to earth to teach us about ourselves.

That she resigned as the most highly paid and influential editor of the most successful magazine, ‘McClure’s’ in New York City, this girl-woman from Red Cloud, because the magazine kept her from writing is quite a story in itself. Be glad she did.

Led by that man of limited ability and unlimited ego, Ernest Hemingway, she is often disparaged by the literati. So be it. Theirs is the loss. Let them sup on the cant.

Her books earned many favourable reviews and a Pulitzer Prize, but more important, millions of Readers.

This film is more explicit about the lesbian relationship(s) than anything at the Cather Center, but leaves open the question of which her friendship with two other women was erotic. (Figure it out, Mr Spock.) All done with a respectful tact. Ergo not done by journalists.

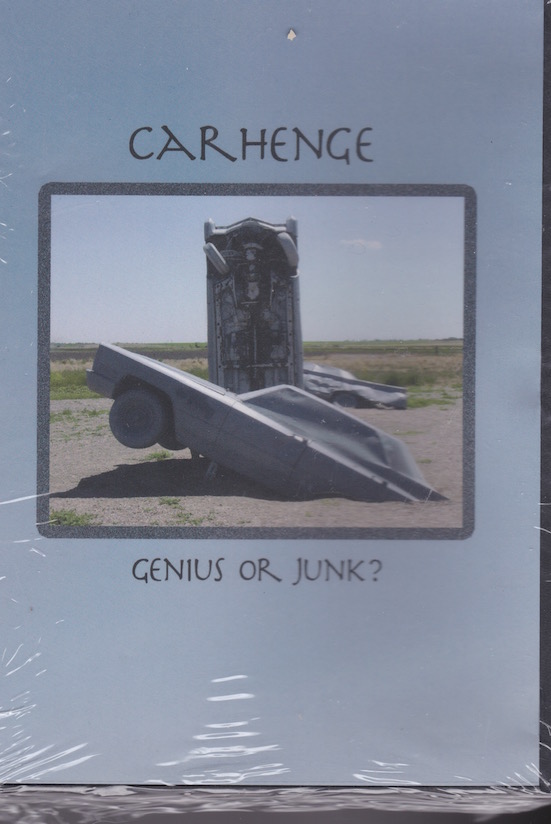

CarHenge: Genius or Junk? (30 minutes, DVD) (2005)

Welcome to Alliance Nebraska, population 8,519, home of CARHENGE.

Carhenge? Just what it sounds like, Mr Spock. It is Stonehenge with cars.

We have seen Carhenge with our very own eyes, and long to see it again!

Alliance and its sister city Chadron (population 5,767), which is about an hour by car due North, were way stations for French explorers and trappers who followed the Platte River. Practice French pronunciation on each: Alliance, Chadron, and Platte, and voila!

This video is an account of the origin, creation, and development of Carhenge, featuring the founder, Jim Reinders, who discovered his home was not his castle even on the Sandhills. There are interviews with townspeople who reacted to Carhenge. Some for it and others against.

I particularly loved the interview with the mayor whose determination to ensure that it is someone else’s problem appealed to me. The first solution was to move the city boundary line a few feet so that Carhenge no longer fell within the zoning laws of Alliance, which laws in turn had to comply with state standards, which have to comply with Federal standards (to qualify for grants and funds, say emergency relief in crisis). So the boundary was moved. Other issues followed about parking, about toilets…..

Some residents objected to this gloried car wreckers yard, as they saw it, as the emblem of the modest little burg. While others saw it, I think, it was hard to tell, as public art to which one must bow. Others heard to slide of credit cards as tourists left I-80 to give it the once over.

Then there were the hoons who vandalised it.

Patiently Mr. Reindeers and his family responded to each assault, verbal, legal, or destructive, and Carhenge has outlasted its critics and despoilers for more than a decade, evolving in the process.

Having read, Jim Work’s krimi ‘A Title to Murder’ which parallels Cargenge to Stonehenge as it figures in Thomas Hardy’s ‘Tess of the Dubervilles,’ I was reminded of Carhenge, and ordered the DVD.

I would like to see the real thing again on my occasional visits to Hastings on the Platte, but it would a major expedition for Alliance is five hours by car. It closer to Denver.

‘Letters to Pastor Jaakob’ (2009)

A little gem from Finland. A blind Lutheran priest takes on as an assistant a paroled murderer, Leila. Father Jaakob has a reputation as an intercessory, I.e., he prays for people and offers advice to those who write to him. While no time period is given it looks like the 1950s. He lives in a forest near a church on a lake. Nature dominates the time and the day.

His only contact with the outside world is the post and the postman. The pastor has long since given up preaching because of blindness, and he lives for those letters.

Leila is angry at the world and makes no effort to cooperate though she is glad to be out of the slammer. She is neither particularly bright nor attractive, and expects people to dislike her. They oblige in the person of the postman.

At first she thinks either the priest is shamming or is a fool. In time she comes to respect, if not share, his faith in a meaningful world. Or so I surmise because the dialogue is like much from Finland, practical and not introspective. And there is little of it. Much is told by the camera.

She also realises that he needs her if he is to live – she reads the letters to him and he needs those letters, just as the writers need him. And she also learns she owes not only her freedom to him, but more, too. No spoiler. His previous letter-reader left for the city to take care of grandchildren.

For some reason never explained the letters dry up and that brings the needs of each to the forefront. Earlier she destroyed some of the letters and perhaps his consequent failure to respond to those, discouraged others from writing. It is not clear, nor need it be. Little of life is that, clear.

In fewer than eighty minute there is more about life in this film than the latest CGI-infected three hour Hollywood brain-buster.

Klaus Hãro, the director.

Klaus Hãro, the director.

It earned place on my list of Finnish movies along with

Leningrad Cowboys (1994)

The Man without a Past (2002)

Vares (2004)

The House of Branching Love (2009)

Rare Exports (2010)

Midsummer night’s tango (2013)

Top marks must go to ‘Rare Exports.’

‘Attack on the Block’ (2011)

This time the aliens try South London instead of East London, and find the locals even tougher!

What’s to like?

The gradually revealed social order amid the outward chaos of the streets, alleys, trash, and detritus of squalid urban life. The additional revelation that for most of the boys in the gang, there is a home to go to but the streets are more exciting.

The mix of races and ages. Mugging passers-by is acceptable to the code but not dealing drugs to brothers.

The foul mouthed swearing is for the streets, not when safe indoors among friends. The swearing and cursing is part of the role of the street-tough.

The implicit social criticism. First the bullies and thugs, then the police, then the drugs, then the guns, all sent to destroy the black migrants of south London.

Then come the aliens. No point in calling the police because they will blame everything on the street toughs and lock them up, leaving the aliens to destroy everyone else. When confronted with the pistol-totting drug lord, the police prefer to arrest the street boys. So much easier. No, the boys from the Block have to look after their own, so they arm up and take on the aliens.

The dope growing nerd, Nick Frost, and his nephew prove to be surprising helpful in the denouement. Some basic sciences goes a long way in this script.

When the newly-moved in nurse tries to explain to the police, who arrive in the end after the street toughs have destroyed the aliens, that the boys saved her and everyone else, the police conclude she has been traumatised by assault, threats, and perhaps rape, Stockholm Syndrome, one officer mutters, while arresting the boys.

The leader of the gang is, by the way, Moses (who led his people to the promised land).

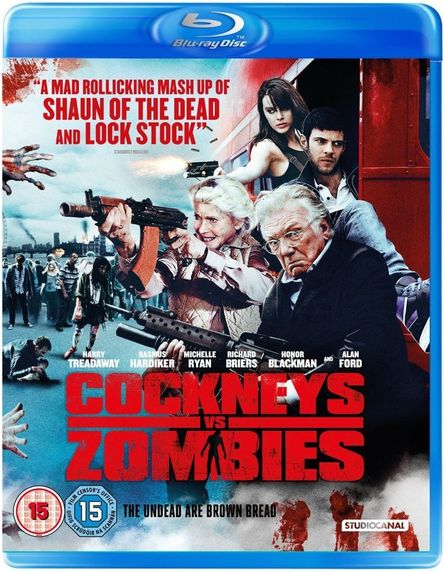

‘Cockneys vs Zombies’ (2012)

From SBS-2 a foul-mouthed slaughter-fest featuring the geriatrics at a nursing home who take on THE ZOMBIES.

I gave it a three and a half snorts rating (four is tops) as I guffawed my way through it.

The nursing home is threatened by a new residential development for the Yuppies who have discovered how handy and cheap East London is. Two grandsons of one of the geriatrics swing into action to come up with the dosh to help out. Their solution is to rob a bank. They assemble a team. This is no A-Team, and includes a klutz, a psycho, an absent minded type, and a cousin who does have some nous. While the lads are busy robbing the bank, the zombies rise and demolish most of the East End.

When the team emerges from the bank, all is devastation. ‘Wh ‘append?, they ask? They are all pretty clueless. But the zombies soon make themselves known. Yes, the have a lot of money now, but who cares! Off they go to save granddad, sure that he will have survived the onslaught, taking along a couple of superfluous hostages who now do not want to be let loose.

What to do? Stay on mission and rescue Granddad.

It is a wild ride and perhaps not best viewed around meal time.

The nursing home includes many familiar faces from Brit cop shows hamming it up, among them Richard Briers who tapes an Uzi to his Zimmer frame, Honor Blackman who knows how to handle a gun, Alan Ford who for years played characters on ‘The Bill’ and similar programs listed in the credits as First Thug, Second Villain, Dudley ‘Tinker’ Sutton whose wheel chair becomes a tank of sorts, and Tony Selby who uses his wooden leg to beat one zombie into pulp.

These seniors have survived Dunkirk, the Blitz, Hitler and World War II, cancer, fifteen years of rationing, the Beatles, divorce, porridge (that is jail time), bell-bottomed trousers, colonial wars, Thatcher, and other catastrophes, a few zombies will not lay them low.

The discerning viewer detects a certain satire here. The Zombies taking over East London surely represent those Yuppies who are driving out the respectable and toiling masses. But then the working class is not spared either, shown to be idle and criminal in the McGuire family.

That it rates a measly 5.9/10 from 14,386 votes on the Internet Movies DataBase confirms a lot about the people to do those ratings, none of it good. There are sixty-eight reviews and I do not recommend reading any of them but I do recommend watching it, though I fear some knowledge of Brit cops shows, personnel, and conventions, will add some seasoning denied those without this background knowledge.

‘Spear’ a film by the Bangarra Dance Company.

Our last Sydney Festival gig was this film. Through images and dance it conveys the ambiguity of being an aboriginal in contemporary Australia. Note it is not a narrative.

Unlike some of the annual breast beating about Aboriginal Australia that usually occurs on Australia Day and then is quickly filed away, this film is direct without either villains or victims, although there are some cringe-making moments.

A young man undergoes an initiation ritual. Into what? Is he affirming his aboriginal heritage or leaving it behind? Should he do one or the other? What is the past in Arnhem Land? What is the future in Redfern? There is some symbolism interspersed with some very literal and brutal honesty.

Some of the emotions are expressed through dance, somr through symbolic figures. and once and while in words. Mostly it is introspective with some aboriginal language, music, and bird calls. It is spare.

The boy witnesses much and is left to make his own choices, day-by-day.

There was much that I did not get, like the upside down man, but the movement, the intensity, the creativity, they were more than compensation. There is some film on You Tube for samples.

We have seen some of Bangarra’s other productions and found them compelling. Ditto this.

‘Decision at Sundown’ (1957)

Here I am again with another Randolph Scott western movie. This time he plays against type, though it took this viewer a while to realise that. The certainties of the western genre are used as a foil to go further and to go deeper.

Bart Allison (Randolph Scott), is slowly revealed to be a crazed obsessive who stubbornly persists in his destructive ways against all evidence and reason.

Moreover, it is also against genre since westerns invariable take place before a background of wide open spaces. Not so here, where nearly all the action is confined to one cramped interior.

But wait, there is more! It is also against type in the portrayal of the villain, Tate Kimbrough (John Carroll). He certainly seems to have the town under his thumb, but he seems to have accomplished that with some greasy charm, a wad of dosh, and veiled threats, nothing more. As it turns out, the villain is not guilty of the heinous crime, Allison supposes, but Allison will not hear the truth nor accept that exculpation, not even from his best friend, Sam, played by the ever-charming Noah Beery, Jr.

Only later does Allison seem, at least for a few seconds, to realise his colossal folly, but even then he persists in his mad quest for vengeance. This is one of Randolph Scott’s darkest role, made all the darker by the expectations audience bring to his films.

The counter point to Allison’s moral disintegration is the gradual moral reintegration of the town’s people to throw off the yoke of Tate Kimbrough. Shades of ‘High Noon’ (1952), though the threat there was far more visceral and immediate.

The town doctor is a one-man Greek chorus who comments on the folly around him without getting involved in it himself.

In the end there is mano-a-mano shoot-out in the great tradition of the western, but this one has a surprise result. The last line of the film from the doctor says it all. See the film to find out about both the surprise ending and the last line.

The cast is full of familiar faces from 1950s television from the sheriff to the bartender, the barber, the banker, and more.

It offers lessons for film makers any time. In less than 80-minutes we have an ensemble cast, vivid scenery, much debate, some soul searching by both Kimbrough and Allison, violent death, and true love.

There are plot holes here. In the first scene, why is Scott in the stage coach, and why is it necessary for him to stop it with threats to meet his partner? Why could he not get a horse and ride to the meeting? Or why could he not arrange for the stage driver to stop at the locale he wanted, and just get off? Perhaps his threats to stop the stage are meant to indicate just how unreasonable he is to become later.

In the town of Sundown, how did Tate Kimbrough establish his hold? What about him led the decent and upstanding Lucy (Karen Steele) to want to marry him? (There is no affinity between them in a few scenes they share.)

‘Buchanan Rides Alone’ (1957)

Randolph Scott rides onto the screen with the confidence of a man who has emerged victorious in a previous fifty westerns, relaxed and confident. That slow and easy smile is knowing.

Tom Buchanan (Randolph Scott) is returning to West Texas to settle down, having made enough money in Mexico to buy a ranch. He re-enters the United States at the town of Argy. Big mistake. The town is owned by the Argy family, each member of which is more corrupt than the other.

Although the Argys are all stinkers, individually and collectively, they do not amount to much, and it is a foregone conclusion that Buchanan will best them.

Amid this venal bunch, there is Abe Carbo (Craig Stevens, before his ‘Peter Gunn’ days) who advises the Argy patriarch. Carbo seems to have some sense of honour that is not for sale, and becomes a neutral arbiter in the moral equation. Why the Argys tolerate him is a mystery.

The Argys steal Brennan’s swag while trying to lynch him and then to ransom a Mexican boy whom he befriended. The plot is disjointed with too much repetition and too little tension. The Argys have no honour among themselves and fall to bickering, first over Brennan’s stake, and then the Mexican ransom even before they get it. They end up killing each other. The body count rivals some of the riper episodes of ‘Midsomer Murders.’

Buchanan will ride on, alone, while Carbo will take over in Argy for the better.

The screen play has the Elmore Leonard touch in the dialogue, but not in the story line. There is a nice performance by L. Q. Jones as Pecos Bill. Did Craig Stevens ever play a heavy? That reassuring baritone of his is hard to imagine as menacing. The Internet Movie Data Base entry refers to him as a ‘light leading man.’ There I learned that he did dentistry at KU before the acting bug bit him. Sci-Fi fans may remember that he alone saved us from ‘The Deadly Mantis’ in 1957.

Unlike many of Scott’s other westerns there is no damsel in distress for him to rescue.