GoodReads meta-data is 324 pages, rated 2.9 by 108 litizens.

Genre: Krimi

Verdict: Dan (Brown) started here.

The sleuth in change of the City of the Flower in the year of their lord 1300 is Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) is called to the site of a ruined ship in the marshes of the Arno with a manacled and dead crew. Is this a life boat from the Mary Celeste, or what? Turns out it is ‘or what.’

Florence is ruled by a small but typical committee — shutter! — whose members are Priors, and Dan is one of them. The others are busy with training seminars, bickering over trivialities, and writing this service onto their CVs while not raising a finger. See, it is a typical committee. Only Dan does any prioring work.

He finds on the ghost ship a strange clockwork, which he conceals, least some zealous churchman declare it devilish and destroy it. There is a lot of that around, i.e., churchmen declaring sliced bread the work of the devil, and devouring it least humble people be corrupted.

It seems the Catholic Church has never changed. It loudest exponents are the first to become corrupt to save the humble people from it. If that is too cryptic, think choir boys.

Dan noses around annoying everyone. Florence is full of travellers, many on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and others to AC Milan away games. They are united by Latin and soccer. Then the murders begin among a group of those travellers. The plot got so thick this reader could not stir it.

Meanwhile a charlatan, no relations to Heston, is gulling credulous Republicans with a new Crusade to build a wall. They throw money at him which he happily collects. When Prior Dan sets out to unmask this scoundrel he finds a deeper and darker plot that harks back to the War of Guelphs and Ghibellinis. This conflict was largely familial though various doctrinal and territorial claims were made to cloak the tribal battle for precedence.

Dan is much less inclined than his fellow committee Priors to accept supernatural explanations for everything and even less inclined to favour destroying anything unusual as the devil’s work. The author brings home the suffocating and hypocritical environment of the time and place very well. While Dan is pious he sees all as part of the divine plan and wants to understand it, not whack it with a sword.

The last great Holy Roman Emperor was Frederick II (1194–1250) of Sicily who was very much larger than life. He travelled widely in the constituents of the Empire and promoted alchemy, astronomy, astrology, and the other arts and sciences of the age. The pope denounced him as the anti-Christ for this support. Freddy also negotiated with Saracens about access to the Holy Lands, and that made him anathema to the Pope. ‘Negotiation, never! The sword, always!’ cried the Pope in the name of the Prince of Peace.

When the Papacy prevailed and Freddy died, it grew avaricious and bloated, and by Dan’s time it was an enemy of Florence, seeking always to extend its grip on the secular city through the sectarian cloisters that abound in the city. (When I spent a semester at the European Universities Institute in Florence I had an office in a one-time monastery. Pretty grim.)

After the Guelphs defeated the Ghibs in 1294, a battle in which Dan distinguished himself, they then split among themselves into Black Guelphs and White Guelphs. The losers of this interniacine conflict went to Ontario where it was a balmy -2 degrees Fahrenheit when I checked this minute. Again the conflict was familial and personal rather than theological or ideological, though inevitably the contestants sought allies on these latter grounds.

The to’ing and fro’ing and the manners and mōres of high medieval Florence are interesting but confusing to the neophyte like me. I never did quite figure out what the point of it all was but nonetheless I will try to SPOIL(ER) it for readers!

The plotters were trying to rekindle the Ghibs. The purpose of the take over was to reclaim Freddy’s mirrors which his court astronomer had made to observe the transmission of light. This was sacrilege because light was God’s creation, or something. So it all had to be done in secret, in the dark. Get it? Why all this had to be played out in Florence was lost on this reader. But the mirrors were the cargo of wrecked ship. Secrecy required the whole crew to be murdered. [Gulp.] UPS could have delivered without all that. Not sure about DHL.

Dotted throughout the text are passages from and references to Dan’s masterwork, the Comedy, which took the name Divine after his death. I have listened to most of it in an Audible book while dog walking years ago. I once met John Ciardi, the foremost English translator of Dan, in that memorable 8 am poetry class that seemed like a good idea for the first and last time at registration.

Giulio Leoni

Giulio Leoni

There a number of titles in this series and I read another one a long time ago. Like this one, I found that one intriguing but confusing. Don’t suppose I will rush to find another title, but if another crops up I would most likely add it to the Kindle.

Wikipedia tells us that Dan’s family was loyal to the Guelphs, a political alliance that supported the Papacy in opposition to the Ghibellines, who were backed by the Holy Roman Emperor. To pursue a political career the young Dan had to join a guild and the easiest entrance exam was pharmacy so he did that. It made some sense, because apothecaries in those days and for centuries to come also sold books, at first DIY book on diet and health, but others, too. That fits with bookish Dan.

Category: Krimi

‘A Man with One of those Faces’ (2016) by Caimh McDonnell

GoodReads meta-data is 362 pages, rated 4.1 by 2252 litizens.

Genre: Krimi

Verdict: Craic!

Slacker Paul ekes out a living in contemporary Dublin by doing six-hours of charity work a week. As long as he does this work a stipend from his late, fabulously wealthy aunt, who despised him, gives him a bare living. He was her only living relative. Her idea was that this stipend would get him started, at long last, on earning a living. She over-estimated her man, because his idea is to scrape along on that stipend. As a consumer he has learned how to make that stipend stretch to cover his very few needs. No bargain bin in Dublin escapes his notice. Most Op Shops are too upmarket for him.

Most of the gratis charity work is visiting inmates and patients at hospices and retirement (old folks) homes in and around Dublin. He has shopped around and found the best set-up, taking into account transport cost to and from, level of demands from clients, opportunities with female staff, and such. Paul is none too bright despite all his scheming. The staff at the institutions verify his work and he lets the elderly clients talk to him and he pretends to be whomever they say. He takes the chits to the lawyer managing the trust fund and gets the Euros. Simple. Too. To last.

Those patients that are assigned to him have no other visitors and are pretty confused about who any one is or where they are. He has one of those non-nondescript faces that they can project onto and he is a good listener.

Then one night, as he listens to a new client rattle on, the dying old man, Mr Brown, riddled with cancer beckons him closer to whisper weakly in his ear, or so he thinks. He moves the chair and leans forward and the old coot stabs Paul in the shoulder with a scissor blade he had secreted in the bed. What with all the tubes and wires on the old cuss the two of them get tangled and fall to the floor, killing the patient who was eighty if a day, and leaving Paul bleeding from the stab wound with additional bumps and bruises.

A routine police investigation soon discovers that the cancer-ridden client was not Mr Brown but rather Moriarty long since thought deceased in Montevideo. Whoa! Where has he been these last thirty years and what has he been doing? Who did he think Paul was that he wanted to stab him? None of this interests Paul, until….

It get worse when Paul barely escapes another much younger villain. His car is booby trapped. He is on the run! He blames the nurse who sent him to listen to Moriarty and she feels guilty enough to club together with him, because it seems someone is trying to kill her, too. Indeed anyone is a target who had anything to do with Moriarty at the hospice.

The pace is fast and furious. The throw-away lines are many. The Irish idioms are delightful. Much ground is covered in and around Dublin. Little is as it seems: The beautiful TV journalist is rancid. The upright police commissioner isn’t. The shifty cabinet minister is honest. The objectionable husband (never mind the details) is a wounded lion. The helpless shut-in is far from helpless. Even the dead are not what they seem.

Hurling figures in the story, as does Guiness so we know it is Irish.

The characters who pass in review include Bunny, the hurling coach who never bluffs, Dorothy who lied about the gun collection of her late husband, Detective Inspector Stewart who may be the last and only honest Gardià in All Ireland, pregnant lawyer Nora whose taser is illegal and all the more welcome for it, but nary a priest though the pews were near full.

Glad I read it on Kindle since I could look up the Irishisms as I went. It is the first of series of four or five titles by Caimh McDonnell.

I started the next one a few hours after finishing this one, and finished them all since I drafted this post. Craic!

‘Island of the Mad’ (2018) by Laurie King

The fifteenth in the series featuring Sherlock Holmes and his young wife Mary Russell.

This time the dynamic duo come to the aid of Mad Woman, whose madness is to be a lesbian and have a very unpleasant brother, who in addition to sexual harassment, rape, and theft, also wears a blackshirt when visiting Italy. What a package is this straw Marquess.

But the shenanigans give occasion for Mary Russell to break into Bethlehem Royal Hospital, better known as Bedlam. Thereafter the fashion show moves to Venice and the eponymous island, Poveglia.

There the twosome meet Elsa Maxwell (1893-1963) and Cole Porter (1891-1964) of Indiana. She was born in Keokuk Iowa (been there) during a theatrical performance, and pretty much thereafter never left the stage of her own making.

Maxwell in 1933

Maxwell in 1933

Professor Wiki describes her as a songwriter, gossip columnist, radio presenter, and professional hostess. Prof also credits her with engendering the treasure hunt and the scavenger hunt as party pastimes.

There is a nice study of Porter in these pages and his intense relationship with Linda, his wife.

The palazzo the Porters rented in Venice. Porter once hired the Ballet Russe to entertain at a party there.

The palazzo the Porters rented in Venice. Porter once hired the Ballet Russe to entertain at a party there.

There is very little sleuthing. Though much of the plot is hidden in plain sight, and that is a nice trick. Many of the things seen and done are taken figuratively, only later to realise they were literal. Though I never did figure out what the brother in the white coat was doing, or quite how Mussolini’s wife related to things. There is also some insight into how Bedlam worked. The research shows, but alas some of its presentation is laboured.

Much too much padding about the fashions and morēs of rich and infamous in corrupt and decadent Venice of 1925. Hmm.

Yet it is remarkable that Laurie King has sustained this series since 1994 through fifteen titles and one collection of short stories.

‘Murder Chez Proust’ aka ‘Meurte chez Tante Lèonie’ (1994) by Estelle Monbrun

GoodReads meta-data is 256 pages rated 3.0 by 27 litizens.

Verdict: Best for Proustians

A small conference of Proustians gathers at Illiers in Aunt Lèonie’s house now a museum dedicated to the sickly Marcel. The organisers include the unscrupulous Adeline whose speciality is blackmailing others with her own remembrances of things past. She brow beats her timid secretary who is also at the mercy of her PhD dissertation supervisor, a man combining all the worst features of a god-professor, one who smokes. To add to the spice, Adeline has both a lover, who really does love her, and a fiancee. Neither of whom see her faults, so readily apparent to others. In the case of these two men, love is not only blind, but deaf and dumb.

In addition to the locals, a party of American stereotypes has descended on the conference. Well, the French did invent the concept of ‘chauvinism.’

The plot thickens when Adeline is found dead in the house museum. Inspector Jean-Pierre Foucheroux is there to investigate along with his sergeant Leila Djemani. These two soon establish a long list of people with motives to harm Adeline, including all those mentioned above and more. In fact, just about anyone who ever met her.

There are some apposite Proust references, but never enough to satisfy a Proustian and too many for others. There is the usual bluster from witnesses, and the secretary is so timid it is hard to believe she is a Parisienne of thirty.

Foucheroux and Djemani (nicknamed Gimpy and Chipmunk by colleagues) make a good pair of sleuths, and I liked the context. But the pace is slowed by Foucheroux’s backstory, a matter of indifference and irritation to me. While the characterisations are largely cardboard, I did love the displays of scholarly pretension in several of them. That part rang true. God-professors, indeed.

Estelle Monbrun

Estelle Monbrun

The author is a teacher who has no doubt seen all of these characteristics on display more than once. She has several other titles of the same ilk.

As I was finishing this book, I thought it so-so. Then I read the author’s afterward, which I found charming, informative, and engaging. Maybe I will read another one. She being a serious literary scholar had no ambition to write a novel, until moving to St Louis and discovering the necessity raking leaves.

Huh?

She went at leaf raking with such conviction that it led to a herniated disk, and while lying abed contemplating her errors, lacking the concentration to bandy lit crit, she wrote this krimi. By placing it is chez Proust, by dotting it with Proust bons mots, by populating it with Proust enthusiasts, she hoped it might entice some readers to turn to the man himself. The pleasure in forming that ambition led her on to other writers, e.g., Collete, Montaigne, and more.

Moi, I never went at leaf raking with conviction, though I have certainly gone at it, marvelling at how many leaves a couple of trees drop. The last time I did this I had to stuff them into large orange bags because these were collected to later be opened and the leaves shredded and the bags re-used. Well that was the story. However the low bid contractor had taken the money and run, and the bags were all going — unopened — into land fill. But we rakers, until the story was blown, had the comfort of supposing the work of bag stuffing had an environmental benefit. Ha, ha, ha. OK but you try stuffing endless leaves into orange bags to see how much fun it is.

‘Below the Clock’ (1936) by J. V. Turner

Genre: Krimi

Goodreads meta-data is 282 pages, rated 3.64 by 11 litizens

Verdict: Lifeless is the kindest thing to be said.

When Amazon’s mechanical Turk suggested this title, I was tempted because of the context, namely Westminster. That a Chancellor of the Exchequer might die — murdered — at the dispatch box delivering a budget seemed a neat set-up. So I acquired and started to read it.

I did finish it but only by some quick thumb work on the Kindle to flick through the pages and pages in which nothing happens very slowly. It is consists nearly entirely of conversations, many belaboured to be clever, I guess, but succeed better at being irritating, annoying, and distracting. Nor were the characters either well defined nor distinguished one from another.

Finally, the protagonist is intended to be colourful, I guess, but succeeds in being petty and pompous. His ‘violently coloured’ and occasionally ‘virulently coloured’ handkerchief is much flourished. Aaargh. Note that this is the seventh in the series.

While there is much going back and forth, this reader never got any sense of the geography or ethnology of the House of Commons, its nooks and crannies or its denizens, though it must have them by the dozens.

Then there are the many typographical errors. It is hard to believe they were in the original edition when copy editors prepared books for publication. The mystery is how they crept in. Via OCR software is one possibility without the mediation of a copy editor.

J V Turner is a pseudonym for David Hume. Nor that David Hume.

J V Turner is a pseudonym for David Hume. Nor that David Hume.

I am sure that someone on GoodReads says it the best book ever published. Indeed among the eleven raters, there are two at 5.

‘The Flaxborough Crab’ (1969) and ‘Broomsticks over Flaxborough’ (1972) by Colin Watson.

Genre: Krimi

Goodreads meta-data is ‘The Flaxborough Crab’ is 176 pages, rated 3.98 by 110 litizens

‘Broomsticks over Flaxborough’ is 192 page, rated 3.95 by 103 litizens.

Verdict: No more.

I liked ‘The Flaxborough Crab’ for its mordant humour and sly exposition. A village doctor taking part in a clinical trial carefully prescribes a trial drug, and things get out of hand, or in hand. The drug has viagra side effects with the result that ….

Well, some of it is amusing. Some annoying, and some threatening. Despite the serious subject matter of sexual assault, not to mention murder, Watson manages to make it light hearted. No one is ever harmed because the codgers reacting to the drug are well past it try though they might. The palate darkens when the drug company intervenes to cover its error.

Especially amusing is the opening scene when a librarian deals with a would-be assailant by cracking his head against a tree. One to stop him and twice to get silly ideas out of what is left of his head.

After reading this guilty pleasure I tried ‘Broomsticks over Flaxborough.’ I found it less successful. It seemed padded with a parody of advertising speak that had nothing to do with either the place, the plot, or the principals yet on it went. The first few pages were amusing but the repetition soon put that paid.

Colin Watson (1920-1983)

Colin Watson (1920-1983)

Watson’s characters are well drawn, but given too little to do, and there is virtually no policing. Just stirring around waiting for the villains to blunder.

There are ten of other titles in the series, and I am uncertain if I will continue with them.

Four of the Flaxborough stories were adapted for a short-lived BBC television series in 1977 called ‘Murder Most English: A Flaxborough Chronicle.’ There were seven fifty-minute episodes with Anton Rodgers in the lead. They are amusing, though sometimes hard to follow, and leaden in pace. Later episodes are enlivened a bit by Miss Teatime. The production values were Filene’s Basement. However the acting was superb from one and all, including the ever reliable Moray Watson. It was a precursor of ‘Midsomer Murders’ in its picture of the quaint English village as a satanic pit.

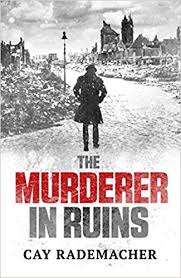

‘The Murderer in Ruins’ (2016 ) by Cay Rademacher

Genre: Krimi

GoodReads meta-data is 334 pages rated 3.9/5 by 539 litizens.

Verdict: Compelling.

January 1947, Hamburg Germany is city in ruins and a city of paradox. It is depopulated and overpopulated. Depopulated by the war, by the bombing, by the deprivations….tens of thousands died, many who could left. Overpopulated by Displaced Persons – millions of them roaming Europe at the time, camp internees, returning German POWs, German refugees from the East, Russian deserters, and more.

Because it was a major seaport on a major transport waterway, the Elbe, because most of the U-boats were built there, because it lay within range of the RAF, Hamburg was subjected to constant air attack for five plus years. From July 1943 the air raids were obliteration bombing aimed at the industrial and attendant working class areas of Hamburg. Because precision bombing was then, as now, largely a fiction for popular consumption, the bombs fell where they may.

What became the British Army of the Rhine occupies Hamburg and environs with an experienced colonial hand.

Then came the hard winter in which the story is set. Both the roads and railroads were badly damaged by bombing, and now the weather has rendered them useless. The trains cannot run. The roads are impassable. The Baltic winds drive the -25C temperature into the bone. It has been much too cold to snow for weeks. In this weather the Brits mostly stay indoors, near the heat. They have plenty of everything, and stealing from them is crucial to the blackmarket.

Much of the population is homeless, living in basement ruins, lean-tos, or cobbled together Nissan huts surplused by the Brits. Most are dressed in the rags, clothes they have had on since 1944. Most wear all their clothes at once for warmth, but also to keep others from stealing them.

In the last years every tree has been cut for fire wood. Coal is unknown. Medicine is beyond price. With the closure of transport for weeks, neither wood nor coal can be trucked in. Food is vanishing. Everyday people die in the street of starvation, malnutrition, exposure, disease and simply freeze to death.

Death in the streets. Starvation, malnutrition, and disease.

Death in the streets. Starvation, malnutrition, and disease.

The Third Man would find this all familiar territory.

DeNazification has gone full tilt. Expelling Naziis from the police, courts, law, hospitals and so on. Necessary but disruptive to the workings of the city. Expatriate Germans who got out are returning to this new world, but many are out of depth in this situation. False identity papers are a thriving black market. Since few paper records have survived the firestorms of the bombings, claiming identity is common.

Could things be any worse? This nightmare world is far more disturbing and disjointed than any dystopia conjured in the Sy Fy films treated on this blog. This environ and the city of Hamburg itself is the major actor in the novel.

Then it gets worse when a murder victim is found, naked and frozen into the surface in a bombed ruin. Then another, and another. Can it get any worse? Yes. The first victim was a young woman. The second an elderly man. The third a child. The fourth, an older woman. Each garrotted, a method much favoured by Naziis as degrading and economical.

Inspector Frank Stave with a stiff leg that kept him out of the Wehrmacht and much baggage is landed with the investigation, aided by a British liaison officer, and a new vice detective. His loyal office assistant does what she can. There are wheels within wheels in this circle.

The strength of the book is the context. The ice freezing on the windows of unheated bedrooms. The flapping of roof tiles in the Arctic gusts. The odors which penetrate even the sub-zero temperatures. The desolation of the streets. The exhaustion of the people. The flow of humanity in the Displaced Persons of every nation, race, and creed. Everyone is suspicious and fearful of everyone else pace Thomas Hobbes’s state of nature. The desperate efforts of Jews to get to Palestine. Ominous rumbling about what the malevolent god in the Kremlin might do next.

The author is no apologist for the Reich.

Cay Rademacher

Cay Rademacher

The Hunger Winter of 1946-1947 was bad all over Northern Europe, made worse by the destruction visited by the Naziis in Norway, Denmark, Poland, Netherlands, and France. As Stave muses, we brought this on ourselves and now we have to endure it.

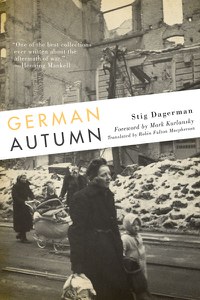

On the terrible conditions in Germany read Stig Dagerman’s ‘The German Autumn’ (1947), though when I read this years ago while travelling in Sweden I found it to be an apology for the Reich.

Back to the book in hand, in contrast to the environment, the characterisations are not particularly compelling, and as is usual there is far too much sympathy-jerking backstory for Stave. This volume is the first of a series and I will certainly try another.

I quibbled about some of the terminology. Those who informed on others were styled by several characters as ‘grasses’ a British term of the 1960s. Would a German have used that expression in 1947. There were other instances of the same sort that distracted this reader.

‘Thumbprint’ (1936) by Friedrich Glauser

Goodreads meta-data is 200 pages, over-rated 3.74 by 226 litizens.

Genre: krimi, police procedural.

Verdict: a curiosity of the place and time. A forced march to finish it.

Set in the Swiss alps in the early 1930s when radio was a novelty. A local is found dead. Was it suicide or murder? Everyone speaks Schweizerdeutsch in which ‘Chabis’ is an oath.

Not to be confused with Chablis.

Into this isolated mountain top community comes Detective Sergeant Studer from the distant Canton to find out which is which. He takes up residence and observes the locals. The bar owner. The nursery man and his staff. The family of the deceased. Creditors. Trees. Swains. Rivals. That is something like the Maigret approach but the hands of this cuckoo clock are heavier by far. As far as this reader can report no thumbprint figures in the story.

Masochists can find out more than they should know by reading the thirty reviews on GoodReads.

Friedrich Glauser (1896-1938) was diagnosed schizophrenic, addicted to morphine, dabbled with heroin, and was intoxicated when he could not get drugs. He spent most of his life in psychiatric wards, insane asylums, and prisons. That experience makes him well qualified, ahem, as well qualified, as most journalists, to comment on the human condition.

Friedrich Glauser (1896-1938) was diagnosed schizophrenic, addicted to morphine, dabbled with heroin, and was intoxicated when he could not get drugs. He spent most of his life in psychiatric wards, insane asylums, and prisons. That experience makes him well qualified, ahem, as well qualified, as most journalists, to comment on the human condition.

There are two or three other titles with Studer. They are unlikely to be disturbed by this reader.

‘The Miernik Dossier’ (1973) by Charles McCarry

GoodReads meta-data is 267 pages, rated by 3.87 by 1375 litizens.

Genre: thriller

Verdict: Unusual in the telling.

It is deep in the heart of the Cold War of 1959 and the Russkies have their eyes on East Africa. Spy and counter-spy vie to manipulate the natives. It centers around a group from a UN agency housed in Geneva which includes a Yankee doodle, a Polack, a Magyar, a Sudanese princeling, a MI6er, and others who embark on a drive from Geneva to Khartoum. Sure.

While the journey is as fantastic as anything Jules Verne conjured, the characterisations are nicely done. No one is quite whom they seem to be, and yet perhaps they are. Even at the end, it is not at all clear to this reader whether Miernik was a villain, though he certainly was a victim.

What is unusual is in the telling. It reads like a dossier that collects and combines testimony, written reports by observers, diary entries from protagonists, archival material about them, analysis by Langley desk jockeys, wiretap transcriptions, post hoc interviews, radio intercepts, case officer cables, opened mail, entries from the CIA Fact Book, field briefings, and such. While there is a master narrative with an arc, it is by no means told as a story. Though in its own way it is, and the story unfolds in these several different registers. The ending is open, but not empty.

Charles McCarry

Charles McCarry

This is the first title in a long series featuring Yankee Doodle, namely Paul Christopher. Alan Furst ranks it highly and that persuaded me to give it a try. Not sure, but inclined to try another.

‘Dead Lions’ (2013) by Mick Herron

Goodreads meta-data is 4.2/5 by 2745 litizens.

Genre: Thriller diller.

Verdict: The study in organisational pathologies continues.

We used to teach something call Org Theory which bore little relation to Org Practice. This book does. Anyone who works in a large organisation will recognise the pathologies exhibited by many of the characters.

The set-up? Two of the Slough House crew are seconded by James Webb, known as Spider, to provide purely nominal security for a visiting Russian tycoon. Why two slow horses for the job, oh, because there is flap on at the Park. Something about office furniture. As always there is never any paperwork to justify the assignment. No paper trail for the FOI rats to find.

Why did I find it credible that a mighty organisation like the Secret Squirrels of MI5 might grind to a halt while an argument with accountants about office furniture takes precedence. Goal displacement comes in many forms. Of course, the furniture is only a means. The end is for two ambitious opponents to fight for supremacy within the organisation. The battle ground? An Eames chair.

Both of the slows, Min and Louise, hope this assignment might restore them to the shining light of the Park, ending their tedious exile to the outer darkness of Slough House, which per the earlier review on this blog is neither in Slough nor a house.

Webb is counting on that motivation to preclude them asking too many questions about this verbal secondment. In meeting them directly he bypasses the supremo of Slough House, Lamb.

There are so many wheels within wheels that my head got in a spin. Rather try to unravel that I offer a few remarks. Nit picking perhaps.

One of the salutary lessons is how easy it is to be fooled if one wants to fooled. Webb’s bit on the bait after reading all about the Russian on the Russkie’s web site. He found there flattering portraits from the ‘Financial Times,’ interviews in ‘Der Spiegel,’ and testimonials from here and there. He looked no further. It was not until Tech Boy Rod cross-checked these excerpts on the Russian’s blog with the original sources that Webb learned, much too late, that they were fake news. There were no laudatory accounts on the pink pages of the ‘Financial Times’ nor in the Gothic script headlines of ‘Der Spiegel.’

What have teachers said since Odysseus returned? Check the original to see if there really was a horse.

Webb did not verify anything because he dearly loved the idea of doing a favour for major player in Russia, a favour that could be cashed later. Ergo, he saw what he wanted to see and nothing more. In his case a successful deal would lead to a promotion up the greasy org pole. Once promoted he would move on away from any fallout anyway.

That is the other lesson. Later when asked who set up the contact, Webb tried to make it sound like his initiative. It wasn’t but he wanted the credit for spotting the possibility of indebting this fellow. When finally he later reluctantly admits that the Russian contacted him first, the tale takes on a different light. It seems it was Webb who was being reeled in and not the Russkie.

The London sky line these days.

The London sky line these days.

Back to those nits, I found it hard to believe that Dickie would spot the hood quite that easily after all those years. Equally hard to believe was that Dickie did not wonder why it was so easy. Likewise that hood’s boss had lived quietly in England for nearly twenty years seemed a stretch, and in two different places. Even more so the villain’s faith in the dead lions, of whom in the end we learn nothing.

There a few more quibbles but that is what they are quibbles.

Less and less in writing is one legacy of Prime Minister Tony Blair, or so I have been told by a one-time inmate of Number Ten. In that administration, verbal communication became the order of the day to avoid written records. Freedom of Information applies only to what is in writing, after all.