The Salamander is an arsonist in Occupied Lyons in 1943. A fire in a cinema immolated nearly two hundred patrons on a freezing winter’s night.

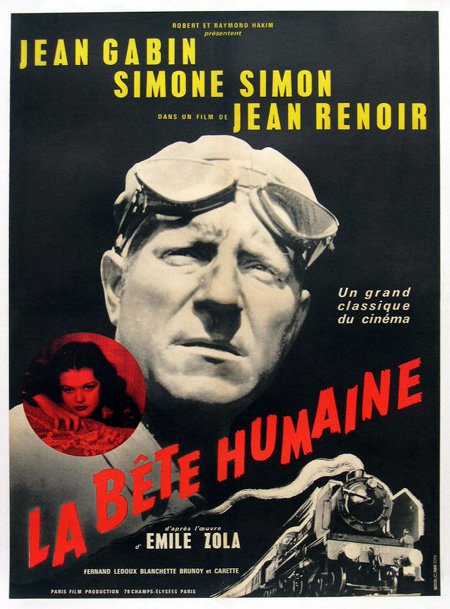

Screening was ‘La Bête Humaine’ (1938) from the novel by Émile Zola and realised by Jean Renoir. Many of the victims of the fire were railway workers and their families.

The central characters in the celluloid story were railway workers led by the peerless Jean Gabin before his face was scarred by German shrapnel in 1943 in North Africa. Many rail lines converge on Lyons, giving it a large resident population of the chemin de fer.

The freezing weather, absence of materials and expertise, and infighting among the responsibles in the civic administration combine to preclude any forensic investigation. There is a very great deal of duck and cover. Then by chance a German fire chief just happens to show up and throws his weight around, seemingly determined in all but word to misdirect and confuse. Yet he must be there for a reason.

The Nazi commandant is one Klaus Barbie, young, educated, debonair, sophisticated, handsome, bilingual, and blood thirsty, a soft-spoken vampire.

Called the Butcher of Lyons for good reason.

Called the Butcher of Lyons for good reason.

Was the fire an act of the Résistance that somehow went wrong, or internecine conflict among factions of the Résistance? Either is possible. Was it Klaus Barbie’s way of attacking the Résistance? This is certainly within the bounds of possibility. And if he did, he might prefer not to publicise it, just to trade on the doubt. Or is a murderous arsonist at large threatening one and all?

A large gathering of hundreds of nasty Nazis is scheduled for Lyons very soon, and to allow for the histrionics of their conclave it will be convened in a huge, old opera house full of dry timber, a catacomb of rooms, with a maze of gantries and catwalks that have never been mapped, side entrances, underground loading docks, concealed exits for divas to elude adoring fans, and other mysteries. In short, an arsonist’s delight and a nightmare to police.

Barbie will not delay the meeting of the coven. To do so would damage his prestige and be an admission that he cannot control Lyons. Uh huh. Is that because the first fire was his and he feels safe, or is it just arrogance? Not even his superiors in Paris are sure and so they send St Cyr and Kohler in case there is a firebug at work. Of course, if a Nazi barbecue occurred the retaliation is unthinkable and that knowledge motivates St Cyr and Kohler to superhuman efforts, and writer Janes spares them nothing.

Kohler is a good German but not a good Nazi. St Cyr is a good cop and patriot, but crime is crime.

There are the usual plot twists. In this outing St Cyr seems unstable, accusing nearly everyone he mets of the crimes. Kohler, for once, has cut back on benzedrine and is calm by comparison, though he is caught with pants down and survives.

There is a great deal of description that goes beyond setting the scene. This is an early entry in the series and the writing is uneven. But the portrayal of Barbie is ambitious and measured. Mad and bad, yes, but controlled and calculating, too, and well aware of the fact that his own superiors could cut his throat at anytime for reasons of their own. As always the stifling and exhausting atmosphere of the Occupation is the principal character.

But the greatest fault is the presentation on the Kindle. The text is continuous even when it cuts back and for the between Kohler and St Cyr. Kohler is in one part of the city creeping through cellars looking for phosphorous and St Cyr is at a hotel checking on guests and luggage. When the scene changes from one paragraph to another there is no signpost of any kind, no blank line, no asterisk, no signal in the text. Ergo I was taxed to re-read many paragraphs when I realised it had switched from one to another. The publisher bears responsibility for this needless levy on my time and patience. Tsk, tsk, and tsk.

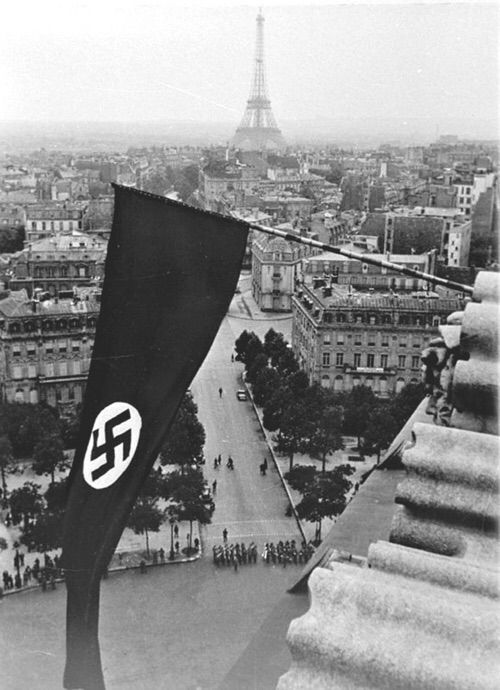

When reading Marc Bloch’s memoir ‘Strange Defeat’ (1940) for the first time years ago, I had a conversation with a very intelligent philosopher who found my curiosity about Occupied France odd. His line was that the defeat in 1940 was the cleansing failure of a corrupt capitalist regime. And after all, as Bloch notes, life went on the day after pretty much as always, hence Bloch’s title. I did protest to this intellect that changes came, but these, I was told, I had got our of proportion. Ah but I continued to protest, Bloch himself joined the Résistance and was captured, tortured, and killed by the Nazis. This fact was a mere bagatelle to my interlocutor. Bloch brought it on himself that was his line. Really nothing had changed from one day to the next with the change of the flag. That philosopher ascended to the professorship confident in his judgement. All very like those academic apologists for Pol Pot, Mao, and all the other mass murders.

St Cyr and Kohler know what this great intellect did not, does not, know, reality comes through the skin.

Category: Krimi

‘Gypsy’ (1999) by J. Robert Janes

It is Occupied Paris 1943, and a series of robberies demand the attention of the luckless duo of Louis St Cyr and Hermann Kohler. The robberies are bold, vast, and deft. But this is no mere thief because fatal booby traps have been left behind to discourage police investigation. Stealing millions of francs from a metro safe is of little consequence, but the theft of industrial diamonds bound for the Reich’s war machine is a red alarm, and our exhausted heroes are called in. Much has been said about them in earlier posts and will not be repeated here.

As usual no one will tell the the truth. As usual there are threats. As usual there are misleading clues. What is unusual is the audacity of the crimes, even high ranking Nazis in occupied Paris are been relieved of valuables they had just stolen from Jews! Audacious also in that three crimes were perpetrated in one night alone! Worse the booby traps have claimed victims, a chamber maid come to clean a room, a flic who opened a door, and a bomb disposal squad whose members should have known better. The villain also tries to eliminate St Cyr and Kohler; this a joker who plays for keeps.

The perpetrator, it emerges, is called The Gypsy, because part of his childhood was spent with some Romani people. Though he himself is tall, Aryan in appearance with the blond hair, and piercing blue eyes of a film star combined with multilingual charm and confidence. The irony is that his appearance and the Nazi uniform he wears, supplied by his would-be control, put him above suspension. His gypsy heritage ostensibly explains his preternatural skills as a thief.

Spoiler alert.

If I have grasped the plot, the Gypsy was in the slammer when the Nazis occupied Oslo. Then some bright Nazi spark had the idea of using him to infiltrate a Resistance network in France by inserting him as though he were an English agent. The connection would be made through a one-time girlfriend. What can go wrong? In return for exposing the Resistance network the Gypsy would be allowed to keep any loot he collected and sent on to Spain. (As if.) The members of the Resistance group he reveals would of course be tortured and murdered. The assumption was that the loot would come from the French, not Nazis themselves. So much for assumptions.

Once released, equipped, briefed, financed, and in France, however, the Gypsy pursues his own agenda. He slips his watchers, he manipulates the girlfriend into the frame and disappears. Then the robberies occur in rapid succession.

Now I may have gotten muddled because Janes’s elliptic style shows no mercy to slow wits. There is never a summation at the end in the Agatha Christie manner. But it seems the Gypsy had an earlier career of theft in Berlin where he stole from Nazis with great success until the Norwegians nabbed him. So far so good.

Meanwhile, the bright Nazi spark who loosened the Gypsy now tries to blame the crime wave onto (1) the Resistance and/or (2) St Cyr and Kohler. To that end this Nazi takes hostages, beats witnesses, and generally shrieks at one and all. If he cannot shift the blame, the axe will fall on him, no metaphor intended. Again I follow.

But what I do not follow is this. The Resistance network targeted was inactive, inert, and consisted of three well-meaning women who had done nothing and were never likely to do so. Nor did they have contact with others in the Resistance. They hardly seem a high profile target for such a far fetched and elaborate effort. That part I do not get.

Nor does the denouement make much sense to this reader. That these three women contrive and execute such a plan once the Gypsy shows himself is beyond my suspension of disbelief. That they nearly spontaneously concocted and implemented the plan is just not credible. They managed to out manoeuvre the Gypsy, the Nazis and the allied goons, and our heroes. If they were able to do that, well, why did they not do more for the Resistance?

Nor did I ever fathom what the Gypsy’s agenda was, apart form thieving for its own sake. He is simply a plot device in this outing and denied personality apart from one brief scene in the Metro.

On the other hand, the siege of the hideout is marvellously told as is the evocation of Paris in 1943 when a Nazi victory seemed on the horizon.

As usual our heroes are full of angst! But as usual the reader knows they will somehow square the circle. These two will survive to the next volume in this long running series.

‘The Accordionist’ (2017) by Fred Vargas

The German has long since retired from the Ministry of the Interior where he was am off-budget fixer. That is, he was a trouble-shooter who dealt mainly with criminal matters. If a baffling case was raising media hysteria, the German would be despatched to see what he could do to put a blanket on the fire.

Born Ludwig in Alsace, his few friends know him as Louis but his mother always called him Ludwig and he thinks of himself that way. In retirement he retains his network of contacts socially but they, too, are retiring. A man without family, a man without friends, a man without anything but a vocation – investigation – coupled with persistence and ingenuity, that is the German. Retirement offers him little reason to get up in the morning. He passes the time as a translator, currently working on a biography of the Iron Chancellor, which regrettably does not play into the story, as I had hoped.

Then an old friend, Marthe, brings him a problem. Her simple-minded ward seems to be embroiled in two murders. There is backstory of how he became her ward and then they later drifted apart. The ward was hired over the telephone to deliver pot plants to two women, each of whom was soon thereafter murdered with his finger prints on the door, on some furniture, on the pot plant….

While Ludwig is not convinced the dolt is innocent he owes Marthe a lot, which is not specified, and he is obliged to act on the assumption of dolt innocence. Hmmm. He trades on his past as an agent of the Ministry and first digs into the simple-minded youth’s past. There are ambiguities and gaps but by and large the lad seems within his mental limits an honest toiler, first as a gardener, but one who needs a lot of supervision, and as a busker with an accordion. That latter vocation supplies the title but again it does not play into the story.

The ward was set up to take the fall, as per the krimi manual. Yes, but why him? Is it all being done to get at this young man, or is it by chance that he was selected to serve as a scape goat, along with the murder victims. What could one so simple have done to earn such multiple, mortal enmity?

Following a parallel train of thought Ludwig ponders the two victims, who seem to have no mutual connection as far as he can determine from his police contacts.

He has the assistance of The Three Evangelists who recur in Vargas’s krimis, Mark, Luke, and Mathew. These three perennial graduate students share a house with the uncle of one, himself a retired plod. The three students are men and are students of history, one prehistorian, one a medievalist, the other who speaks only in the language of World War I trench warfare with which he is obsessed.

As the pages turn, each of them adds interpretations, facts, and insights into the mystery. Van Doosler, the uncle upstairs, does the cooking when he feels up to it but is otherwise aloof. Tant pis. I had rather hoped he would figure in the story as more than window dressing.

Fred Vargas, whose books have been purged from ideologically pure women’s libraries because of the name Fred. Amusing, n’est pas?

Fred Vargas, whose books have been purged from ideologically pure women’s libraries because of the name Fred. Amusing, n’est pas?

The title in translation places the focus on the simpleton, but the French is ‘Quand sort la recluse’ which refers to Ludwig stirring, I assume. He certainly is the core of the story. While I gulped it down, as always with a Vargas krimi, I felt it was underdone.

‘The Late Scholar’ (2013) by Jill Paton Walsh

It had to happen sooner or later. Lord Peter Wimsey has become the Duke of Denver, upon the death of his older brother Gerald. That dukes are higher than lords is news to me.

With the title Duke comes ducal responsibilities, most of which were new to Peter Wimsey. There are vexatious relatives, disputatious tenants, ravenous charities, clogged drains in the strangest places, a crumbling pile that is crumble still, elderly retainers to retain, so that when he is called to Oxford, off he goes! What a relief!

When he was but a lord, to him the relatives were polite, the tenants deferential, the charities distant, the drains unknown, the ancestral pile was for holidays, and the retainers retained. As duke, it all changed.

Called to Oxford? One of the Duke of Denver’s entailments is to be The Visitor to a not very distinguished college at Oxford. While every other Oxford college Visitor is a royal of one magnitude of another, this college has the Duke of Denver. Investigation in the muniments room of the aforementioned crumbling pile reveals that generations ago a Duke of Denver handed over some dosh to replace a roof or two at the college and in return for that largesse the title The Visitor was bestowed upon him for his lifetime, but in a subsequent change of the college constitution the limitations ‘his lifetime’ was omitted, perhaps by error.

Well, no matter, an escape to Oxford is most welcome for the poetry quoting, incunabula collecting, Saxon speaking Wimsey. It is a return to lost youth for this old soldier.

Peter is now married to Harriet (née Vane) and it seems to be after World War II and in the early 1950s. The stately home is crumbling in part because of a fire caused by an errant German bomb and taxation is vexing.

Together they descend on the college to find themselves in the middle of an acrimonious and bitter conflict among the twenty of so fellows of the college over the status of a tenth century book in its library. The conflict is so vitriolic that no one speaks of it! Immediately I found this scenario easy to believe.

These scholars seem to do little else but plot one against another, while seldom is heard a discouraging word from their lips. Backstabbing, undermining, poisonous rumours, slanderous gossip, attribution of venal motives, all communicated by innuendo and sotto voce, these are the weapons of choice. Meanwhile, at high table meals the weather is much discussed. This is brutal realism at its best.

Even the engineers and economists among the brethren have taken sides over this book. On the one hand, the goal is to sell the book to raise money for yet another roof and on the other hand is the over-our-dead-bodies group! Yep, prophecy there.

Each fellow votes in a time honoured, and otherwise incomprehensible, arcane ritual and each poll results in a tie. After three such votes, some of the parties invoke the right to summon The Visitor to adjudicate. Enter the Duke!

While the vote remained tied in those three rounds, the constituency shrank. The senior most fellow, the Warden, went missing and another died falling down stairs. Two others had unlikely accidents, which while damaging, were not fatal, but which precluded participation in the voting ritual. In the best tradition of krimis the ritual does not admit of absentee or proxy voting. Is someone mowing down the voters? Are there two mowers, one on each side of the question, the keepers and the sellers? Are there only two sides to the issue?

Before any Solomonic adjudication can occur there must be sleuthing to find out what is going on.

Harriet takes no convincing to join in, and engages her own distaff Oxford network, and the ever reliable Bunter mines the college servants with his usual dexterity.

Nothing is what it seems to be.

As in C.P. Snow’s Cambridge novels, all of which I have read [Groan!], the scholars do little scholarship but make an enormous fuss over the rituals and prerogatives that fall to them, like passing the port. It is all too credible.

Dorothy Sayers created Wimsey in the 1920s.

While Ian Carmichael brought him to life on the small screen in the 1970s.

Ian Carmichael as Peter Wimsey

Ian Carmichael as Peter Wimsey

Bunter was an older man, and he and Wimsey had been through trench warfare in Flanders together and had survived, thereafter bonded for life, and with a considerable amount of unspoken communication.

Despite the dreadful experience of Flanders, Wimsey (and for that matter, Bunter, too) remains Edwardian in manner and morēs. Wimsey is an enthusiastic and effete dilettante, who quotes obscure poems in dead languages and playwrights unknown all the day long while playing the piano and sporting a monocle. His private collection of incunabula is the envy of museums. His flow of witty banter is without end and without purpose. Noel Coward could not have bettered him as a caricature.

Bunter unfailingly addresses him by his title and always stands in his presence. Always and always. Bunter out butlers even that fellow James Stevens in ‘Remains of the Day’ (1989).

Harriet, mindful of her own modest origins, tries after a fashion to loosen them both up, with little success. Nor does she seem aware of the changing times of the 1950s.

The unalloyed Edwardians Wimsey and Bunter are an odd couple in world of a Labour government and many new social attitudes. Still that is part of the fun.

Like Sherlock Holmes and more recently Hercule Poirot, Wimsey has his re-animators. This is the fourth title by Paton and I have liked it enough to read another. Though I did find it wordy, but Peter is like that. There is much talk, often about nothing much, and too little detection. It must be struggle to be arch and witty when talking about staircases and fence posts, but Wimsey is made to do it. Poor fellow.

Jill Paton Walsh

Jill Paton Walsh

He even indulges in the future subjunctive interrogative at times, such is his mastery of all things Fowler. (Mortimer, skip it. It would take too long to explain.)

Even in the sleepy village I know well, the absence of the senior scholar for three months would be noticed and some effort made to figure how what happened to the missing savant lest the key performance indicators be spoiled.

‘The Treasure of Saint Lazare’ (2014) by John Pearce

Our hero, Eddie Grant, he of the chiseled jaw, martial arts belts, multi-lingual talents, and accomplished lady killer …. [Is there nothing beyond him?]

The set up is this. Ed (I refuse to call a grown man with such a cv as above Eddie) is the son of World War II veteran whose assignment in 1944-1946 was tracking down art looted by Nazis. His father died earlier, in suspicious circumstances that Ed mentions but apparently was not motivated to do anything about at the time. Then the father’s assistant from the wartime assignment dies, again in suspicious circumstances. This assistant left a letter to Ed’s father, not knowing he had predeceased him, and asked that his executor deliver it by hand.

Since the dad is dead the messenger, a daughter, delivers it to Ed. She is of course a beautiful woman who falls under Ed’s spell, taking her place in the queue.

It just so happens that Ed has many contacts in the worlds of policing and art, and these he now mobilises. Why he did not mobilise them when his father died is unknown. Even more mysterious is why he did not mobilise them when his wife and child were murdered after his father’s mysterious death. All of this death is supposed to awaken sympathy I suppose but it just makes Ed seem a jinx and jerk. Four dead before he goes into action.

Then the big black Mercedes limousine appears bearing — as it must — Germans.

So much for subtlety. The plot is by the numbers and the characterisation are connect the dots.

I quit at about 25% on the Kindle. I was reading topic sentences only and flipping on; it was time to move on.

At the start there is much too much backstory forced into the opening pages so that we may appreciate Ed, followed later by extensive and pointless descriptions of hairstyles. clothing, drinks, furnishings, cars, and so on and on. This later I guess is the Paris part. If this superfluous detail were cut to the standard say of Georges Simenon the text would reduce by more than two-thirds. Good grief. Amid all the bland descriptions there is very little story. With John Stuart Mill, I suppose that we know a person by deeds not by the recitation of a backstory. What do I care about the backstory until there is a front story?

Nor is it possible to warm to Ed for whom everything seems to come easily though he moans and groans about it.

This is described as ‘a novel of Paris’ and I wanted to test that proposition. There is much Paris in the early going and I consulted by Michelin map, but then we head off to Orlando in Florida and…. I supposed it gets back to Paris but without me. The Florida trip seems mostly to be an occasion for more pointless description.

After re-reading all of Iain Pears krimis with Jonathan Argyll and Flavia di Stefano chasing lost paintings the reference to a lost Raphael was intriguing, but this treatment is not arresting for this reader.

I had a look at the comments on Good Reads to see what I was missing. I looked at the effusive ones, further confirmation that this source is not credible.

John Pearce

John Pearce

Speaking of sources without credibility, one of the local rags has a weekend feature called something like ‘Books that made me’ in which minor celebrities, well I guess they are but they are unknown to me, list and comment, briefly, on five books that had a formative impact of their being. Nice idea, but the execution is kindergarten.

These celebrities seem not to do much reading and certainly not of, say, a novel of consequence or a historical study of insight. Instead we have excited drivel over self-help manuals, diet plans, children’s books – see I said kindergarten – and Mills and Boon stories, Alice’s adventures. In some cases it is pretty clear it was a stretch for the subject to think of five books. When one of these pieces refers to ‘Death in Venice,’ ‘Swann’s Way,’ ‘Absalom, Absalom,’ ‘The Iliad,’ ‘Crime and Punishment,’ ‘Hotel Baltimore’ and their kind, let me know.

Arnaldur Indridason, ‘The Shadow District’ (2017)

A krimi set in wartime Reykjavik Iceland in 1944. The island is awash with soldiers and sailors of the Allied forces: Brits, Canadians, French, and mostly Americans. Harbours are dredged, piers built, fuel tanks dug into hillsides, pipelines laid, barracks built everywhere, landing fields levelled, hangers erected, roads paved, concrete bunkers made, ammunition dumps created, and on and on, from 1940. There has been more money spent on the island in those five years than in the previous five hundred years.

With so much money comes loose morals, it would seem, despite the language barriers. While Icelandic men are not off at the war, they are off on construction jobs all over the island, leaving wives, sisters, cousins, and daughters to their own (de)vices.

The setting and the set-up are good. On the plus side is some detail about the impact of this intrusion on Iceland, and not just the sex, but also on nationalism, though that is merely mentioned and not in any way developed. The weather is there, too, but it does not figure in the story, as it did in ‘Trapped.’ There is also a little more about Iceland legends, the hidden people, but again it is a sidebar that is not cemented into the plot.

The execution is not equal to the set-up. First, the story is split between then in 1944 and now in 2000, say. This is a technique I cannot abide because it makes the reader responsible for integration. Second much of both stories, the then and the now, is padding, e.g,

‘I walked up the the three plank steps to the door. I took off my left glove and knocked on the door, and waited, while I put the glove back on. I heard faint sounds insider but the door did not open.

I took my glove off again and knocked on the door again. I put the glove on and waited. And waited.

The door opened. I introduced myself and asked to come in for a word. She said, no. I asked gain very politely. she said no and turned away. I asked once more for a word inside. She said alright.’

Snappy, uh? He then asks her what she saw. She says she saw nothing. He asks her three times and three times she says she saw nothing. Bold, he asks a fourth time, again no result. He leaves, descending the plank steps.

That took about five pages for nothing. He then repeats most of this verbatim to his partner over the next two pages.

While this book is slow, it is not detailed, but rather superficial. Two examples suffice. (1) The Icelandic nationalism is mentioned more than once but never articulated. (2) While there are many soldiers around there is never anything about their role in the war effort or how Icelanders feel about being occupied. Is this war their war? They are, after all, eddas or not, Danes by blood and the German heel is on Denmark, yet that is never even referred to as an issue in the story.

The text, perhaps thanks to the translator, is replete with banalities. If there was a clichéd way to say something, that was the way it was said.

Arnaldur Indridason

Arnaldur Indridason

This is one industrious writer who has three series, the one that includes this title is Reykjavik during World War II, including ‘Silence of the Grave’ (2007), which was adequate, and another series that follows the investigators of Inspector Erlendur, e.g., ‘Jar City’ (2007) which I liked a lot for its meticulous attention to detail, especially in thinking things through. Erlendur as I recall does a lot of thinking. In contrast is the author’s third series ‘Reykjavik Thrillers.’ On the strength of Erlendur I read his ‘Operation Napoleon’ (2012) and regretted it and did not bother to finish it. The list of his titles on Amazon translated into English is long,

While my recollection of Erlendur is strong enough for me to try another, from now on I will pass on the other two serieses.

‘Death of Delos’ (2017) by Gary Corby

Love this series of krimis set in the Athens of Pericles. Nico and Diotima set sail for Delos for she has been chosen to represent her temple at a ceremony on Delos. Indeed it seems the goddess Artemis has chosen her, for her name was picked twice out of an urn. Twice?

The first time her name emerged on a pottery shard from an urn it was rejected and replaced. Why? Because it is not suitable for her to go, being so heavily pregnant. Huh? It is forbidden by Zeus for anyone to die or to be born on the sacred island of Delos. Why did Zeus lay down this law? Because the island was the birth place of Apollo and Artemis, the golden twins, and there shall be no further births there, and a death would desecrate the place.

But when her name came our once again, after a great deal of urn shaking, the priestesses recognised the divine will and off she went, taking husband Nico in tow. All in all a two week jaunt to the Greek islands in high summer seemed like a good idea to escape the heat, humidity, dust, and pressures of Athens, and while Diotima is pregnant there is plenty of time because the ceremony on Delos is but one day and then they can move on to Mykonos for a vacation, and perhaps even the birth of the next generation. What can go wrong?

Ah huh.

While they sail in a gold encrusted ship with a polyglot crew devoted to such ceremonial voyages it is, strangely, accompanied by a fleet of fifty, count ‘em, Athenian navy triremes in war paint, i.e., black.

Delos is marked by the red star.

Delos is marked by the red star.

Just before sailing the hapless Nico was summoned to the great man’s presence and given the word. The great man is Pericles who has made Nico his catspaw for discreet work here and there, often involving the detection of whodunit. Nico can hardly say ‘No!’ to the first man of Athens, as much as he would like to do so, especially this time.

Pericles tells Nico that he — Pericles — will be coming along in those warships, because even then Athens was outspending its Euros and needed some more readies. Readers of ancient history know this sad story, and in Thucydides’s ‘History of the Peloponnesian War’ it stands as an early sign of Athenian corruption. The Athenians have come to steal the treasury of the Delian League (147 members) kept on the sacred island, held in trust by the highest of high priests and priestesses of Apollo and Artemis. The Athenians come armed and ready to take it, if it is not given by the religious guardians. Though what a few hundred clerics and another few hundreds shepherds could do in the face of an onslaught of Athenian marines is not much.

But will the marines risk their immortal souls at the order of Pericles to seize the treasure? He would rather not find out, and so — as always — he tried to talk the highest of the high priests out of the treasure. Pericles is at his glib best and has a smooth and convincing reply to every protest, he thinks. While the formally designated highest most high priest wavers in the face of Pericles’s sophistry, one old curmudgeon does not. Gero is his name and he knows right from wrong whatever Squid Head says, as the irreverent called Pericles for the elongated shape of his head. (Being sensitive to this indication of his alien origin, Pericles almost always wore some kind of hat.)

A standoff ensues. It is for such occasions that Pericles has a confidential agent at hand, one Nico. Gulp! Diotima is firmly on the side of the gods on this one, and she and Nico have words, while he fusses around her with fans and water to keep her and her passenger comfortable.

There were once twelve of these lions protecting the temple.

There were once twelve of these lions protecting the temple.

These are charming stories, this being the seventh, in a series that remains fresh and vivid. Corby continues to mine the historical record for frying pans and fires into to which to sauté Nico and Diotima so that readers can watch them squirm, and squirm they do. While Pericles appoints Nico to suborn Gero, the Highest Priest appoints Diotima to see that no suborning occurs! Well, not quite but close enough.

The plot gets thicker when Gero is found dead with a sacrificial knife in his heart! Whodunit, indeed? A thorough investigation of the treasures and treasuries on Delos reveals….. [Think Enron, think Lehman Bros, think…]

Hardened readers of police procedurals know what is coming next, and it does.

Gary Corby

Gary Corby

I ordered this for the Kindle before it was published and awaited its appearance, then one night after finishing a heavy-duty krimi it appeared in my Kindle Library as if by magic. It was a magic powered by American Express and Amazon in combination. I was delighted and devoured the first chapter that night, despite the alarm set for 6 a.m. the next morning to welcome the builders come to rip out the kitchen and rebuild a Star Trek galley complete with replicator. Power tools at 7 a.m. get the day off to a good start.

All is revealed about the Delian League on Wikipedia. When Pericles came calling in 451 BC the heavy handed Athenian treatment of the League had made it into the Athenian Empire. Previously independent member states like Naxos and Thasos had been coerced, and the tax levy was set to fund the building program on the Acropolis, not to intimidate the Persians. That Pericles might prefer an empire to a committee meeting of 147 members does make a lot of sense.

‘On the Bone’ (2016) by Barbara Nadel

Inspector Cetin Ikmen and his team are back at it once more in the bazaar of Istanbul, awash with Syrian refugees and militant Islamic zealots under the watchful eyes of the security services.

A perfectly unremarkable and pleasant young man staggers to his death on the steps of a church, the victims of a heart attack. Case closed. Wait! Not quite, the routine autopsy accorded such an unexpected death produces a disturbing result.

Istanbul in full swing.

Istanbul in full swing.

Back and forth across Istanbul go Ikmen’s minions and the man himself. Getting nowhere, Ikmen, reluctantly recruits, a one-time criminal computer hacker to find wanna be cannibals on the dark web, fearing that he is giving matches to an arsonist.

Did the dead man knowingly and willingly eat human flesh? If so when, where, and how? If not knowingly or not willingly, what happened? In either case his dead body is itself a crime scene, and this causes the first difficulty because a good muslim is to be buried before the sun goes down. But in the circumstances no higher authority wants to rule on the technicality of what is a crime scene. Instead low level functionaries are left to their own devices.

Ah, how that reminds some of life in large, complex organisations full of self-styled leaders at the top who stay there, in part, by not leading. Does Max Weber cover this somewhere?

Ikmen’s efforts to get one of his superiors to declare the cadaver a crime scene bring out the worst in everyone. They go through the stages of bureaucratic grief when confronted with a career-threatening problem: first, denial. The pathologist must be wrong. But no, the tests are conclusive. Second, anger. Why bring this to me! It is someone else’s responsibility. Go away! But it is your problem as per the organisational chart. Third, bargaining. Let’s find a middle way. Keep the stomach and contents and release the rest of the body, but say nothing. Fourth, depression. One higher authority takes sick leave to avoid further involvement. Only Ikmen accepts the reality and the responsibility that comes with it, because he has no other choice. After all the human flesh consumed came from a victim, and he has to identify that victim and ascertain what happened.

Minor plots go swirling by. On street corners congregate idle young men who dream of martyrdom for Allah. Syrian refugees who cannot speak Turkish struggle to survive out of trash cans. Churches are bombed. Jewish cemeteries vandalised. Russian tourists are buying up property. Public works projects have stopped in mid-stride with the vicissitudes of the regime.

In distant Ankara members of the government seem more preoccupied with in-fighting than with governing. Another verity.

All the further testing done to discredit the finding of human flesh throws up another clue. The flesh has the genetic markers of a very rare disease that almost exclusively afflicts Jews. If the victim was Jewish the narrows the field of inquiry but strews it with social landmines when Ikmen has to seek out Jews. Is he insulting Turks by asking if they are Jewish or have Jewish ancestors? Is his a witch hunt for Jews on behalf of the regime? In the volatile world of contemporary Istanbul who wants to admit to being Jewish if it is an option not to do so.

Barbara Nadel

Barbara Nadel

While I found reading this novel uncomfortable, the ISIS martyrs in the making, the cannibalism, the clash of the Russian mafia with the local rivals, and all the innocents caught in the several crossfires, there is no doubting the author’s skill in putting it all together. The greater is the admiration when one realises this is the eighteenth Ikmen krimi. What an achievement to keep such a long running series fresh. Chapeaux!

When I entered this title onto the software I use to catalogue books the program fetched the metadata and the author came out as Brian Nadel! Wrong!

‘The Road to Ithaca’ (2017) by Ben Pastor.

Martin Bora is a police officer now in the Wehrmacht, assigned to the German embassy in Moscow in 1940 from whence he is dispatched to Crete on the whim of a superior to fetch some Cretan wine. The early scenes in Moscow are interesting period pieces as the allies of convenience dance around each other.

Equally fine are the descriptions of the heat and light in Crete, after the chilly gloom of Moscow. While the weather is different, the social atmosphere in Crete under German occupation is as tense as that in Moscow.

The simple errand of finding the wine and escorting it back balloons out as readers knew it would.

The Germans have only just secured the island.

The German airborne invasion.

The German airborne invasion.

The Greeks have surrendered and the British have once again been driven into the sea, but there are still many British soldiers at large in the hills and dales, and some Cretan armed resistance has begun. It is much more dangerous than Moscow.

In the midst of this volatile situation a British prisoner claims a war crime has occurred and produces photographic evidence of the murder of a household of civilians. Hmm. Best to investigate this ourselves is the German conclusion, and do so before the International Red Cross takes an interest. It would have been a refreshing change from the stereotypes, if one of the Wehrmacht generals wanted the truth to root out indiscipline among his men. Instead it seems one of the victims was an acquaintance of the egregious Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945) and the quickens the pace.

But with Crete largely subdued and the demands of the next offensive now in train, combat troops and field officers are being transferred and reassigned in rapid succession. Ergo the only Wehrmacht officer of sufficient rank with relevant experience who is not subject to a movement order is …Martin Bora.

It is a good set-up. Bora does what all good plods do and interviews the accuser and at the end of one of their discussions when they have sparred is a nice touch. Both are highly educated men and Bora speaks perfect English so has no translator, though there are guards present and many other prisoners milling about. The Brit decides to reveal a secret to Bore to help in the investigation but swears him to secrecy. Then just to make sure the word does not leak out he switches to Latin to provide the clue. Bravo.

Bora meets a local police officer who is resigned to German hegemony and an American archaeologist, a woman, becomes his unwilling guide. Both of these characters are rounded individuals.

To find an eye witness to the events shown in the photographs in the battered camera, Bora takes to mountains of the interior to find a British soldier who allegedly fled that way. In the course of this trek the descriptions of the flora and fauna, the heat and the light are excellent but they become repetitive and thereby frayed.

It is a long way from the tourist resorts now on the coasts.

It is a long way from the tourist resorts now on the coasts.

Less palatable to this reader is Bora’s incessant need to feel sorry for himself, and bore the reader with his back story. How a solider who went through Poland and then France can be so inward looking is the mystery here. This is no Odysseus!

That he and the woman guide are at odds is well done, and unusual in this genre when the femme is usually either a fatale or a conquest. This one is not very femme though she does try to be fatale.

Bora’s meetings with those who have fled to the mountains and those who live there are uneven. The Catalonians he finds there are a cardboard plot device, period. Ditto the distant maidens in the field. Hardly more credible are the Cretan guerrilla band members. More convincing is another archeologist whom Bora finds at a dig in the mountains. Major Busch, Bora’s immediate superior, is also credible.

That Bora begins to think he is on an Homeric odyssey just seems silly. Likewise the resolution of the plot coiling back on itself is so far fetched it would take Apollo astronauts to bring it home. It is not what Aristotle would call a coherent plot.

By the way, the description on the Amazon web site, from which I acquired this book, errs on two counts. It is a not Red Cross representative who is murdered. Nor is Bora sent to investigate the murder, rather he is there when an investigation is needed and he is put to work.

Ben Pastor

Ben Pastor

This title is part of series. Ben Pastor is a woman, one who writes about soldiers, she proclaims on her website.

‘The Man from Berlin’ (2013) by Luke McCallin

Captain Gregor Reinhardt continues to struggle with his conscience in this entry to a police procedural series set in the German Wehrmacht in 1943. He is Abwehr officer, that is, Wehrmacht intelligence service, whose usual task is interrogating prisoners of war. He talks to them rather than beating them, and his makes him odd, but he gets enough results to be insulated from critics, though they circle. A successful detective in Berlin he entered the army to escape the thugs that the new regime of 1935 promoted, and its racial approach to identifying villains. Some escape.

He is in Sarajevo going about his business, trying to focus on the main things and ignore…. [much].

But he is despondent and depressed, his wife has died and he is estranged from his only son who has become a super Nazi. Is life worth living in this Dantesque universe, he might have asked, for he is learned, but he did not.

Then he is assigned a case to investigate and the old policing instincts are aroused, and he has a purpose each day. He meets the usual obstacles and obfuscations readers expect though they are heightened in this Balkan inferno. He presses on, though there are doubts. He meets some truly despicable people, including one of the late victims, a beautiful young woman film-maker who enjoyed torturing Jewish women in front of their children before filming their murders by her Ustaše comrades. If the supply of Jews was low, she would turn to Serbs for such fun.

The book offers a socio-politico topography of war time Yugoslavia, the Chetniks, the Red Partisans, the Ustaše, the Croat Army, the Italian occupation force, and the German, within whose ranks are many deep divides. Only the Italians seem to be civilised and they are a minor player. These groups make shifting formal and informal alliances. In the brew come some British advisors so the plot thickens.

It is a murder that Reinhardt must investigate. One of the victims was the woman film maker and that would be left to the civil police in the puppet state of Croatia, but also murdered a few steps from her was a German army lieutenant. It becomes a joint investigation with the Croat police for whom all acts of villainy, apart from their own, are done by Jews, Gypsies, Serbs, or Reds. Ergo find the nearest Jew and that is the culprit.

This plot is very thick and it just gets thicker. There is much about the city of Sarajevo, its Ottoman and Austrian pasts, its troubled present, and its byways. The divides among the Germans are many and varied. Their are personal animosities, unit competitions, status consciousness to an insane degree, service rivalries, venal as well as moral corruption and incompetence, and the usual assortment of thugs and bullies assembled by krimi writers, most of them wearing uniforms in this instance.

The comeuppance of the primary bully was a delight. (Where do I get one of those Reinhardt specials?) There is also a captivating portrait of a German general with something of Erwin Rommel in him, a war lover. He is in a word, charismatic. Even the jaded and cynical Reinhardt feels the urge to follow where this man leads but tries to resist it, and then realises all is not as it seems. The blue herrings are piled up and neither of the short-priced favourites was the perpetrator. That is enough of a spoiler.

The story Reinhardt tells of one of his famous cases in Berlin is nicely done. He tells the story but suppresses much of the truth, which will sound familiar to anyone who has worked in a large organisation, the backsliding, the backstabbing, the blinding incompetence, the stubborn resistance to the obvious, the incapacity to act in a coordinated fashion. The usual. Then add to that the racial elements and the brew goes from noxious to toxic.

This is the third novel I have read of late featuring such a military police office. Perhaps inspired long ago by ‘The Night of the Generals.’ That is not counting Bernie Gunther whose career I have not followed.