The third entry in this perfectly charming series set in contemporary Mumbai, a world rich with colour and incident.

The plot? A spoiled brat of a Bollywood star is kidnapped, and the stops are pulled out to get him back, to save the blockbuster movie he is starring in, to satisfy his doting mother, to avert a massive insurance payout. There is only one man for the job in all of India, of course.

Chief Inspector Chopra (Ret.), enemy of all crime, and his sidekick, Ganesha, the little elephant, get the call. Everyone knows about police dogs, well Ganesha is a police elephant!

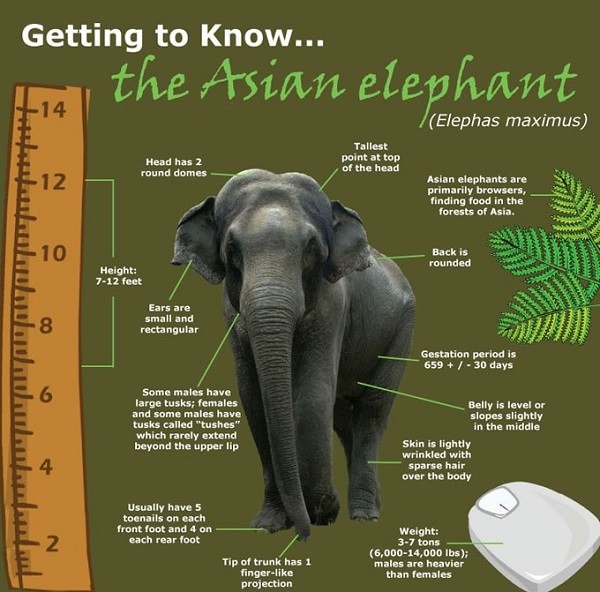

The Asian elephant.

The Asian elephant.

In Bollywood, nothing is as it seems, and Chopra swims through many blue herrings to end up back where it all started. Reality is even more unlikely than the cinema!

Along the way there is much to’ing and fro’ing in Mumbai and a cast of many. Holy days upset the schedule, and Ganesha finds the vital clue and also saves Chopra’s life again. Once more Ganesha proves to be no ordinary elephant.

Meanwhile, Chopra’s trusty assistant settles his own case among the lowest of the low in the Indian caste system, the eunuchs, and learns some things about himself in so doing.

The lowest of the low.

The lowest of the low.

In addition, Poppy, Chopra’s wife, rises to the occasion by staging a daring jailbreak, aided by the ever reliable Ganesha, and the chef’s number two curry! Poppy runs a restaurant and she recruits the chef for the heist. Chopra refuses to take money from friends, so when he needs help, they turn out in force.

Poppy, earlier, made an alliance with the officer who replaced Chopra at the nick, a very belligerent woman, but once she is on your side…. Get a flak jacket!

Then …… That is a spoiler. Delete that.

It works out in the end, though Chopra’s nemesis Deputy Commissioner Rao is not done yet. That is clear. This is a tale of redemption, and ends with Ganesha doing a star turn.

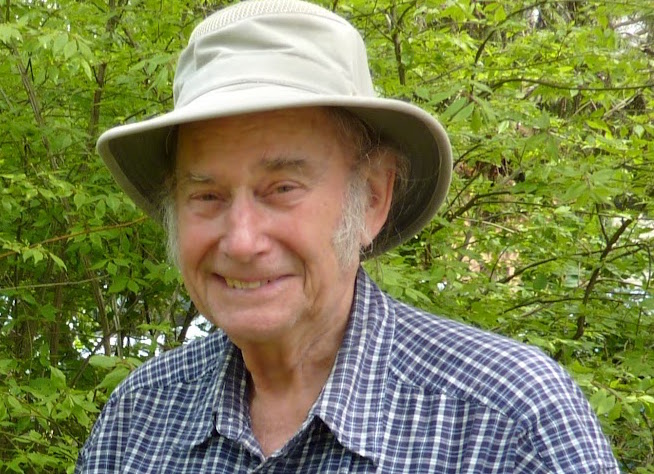

Vaseem Khan, away from the keyboard.

Vaseem Khan, away from the keyboard.

Category: Krimi

Dollmaker (1995) by J. Robert Janes

Inspector Hermann Kohler and Chief Inspector Jean-Louis St-Cyr, an odd couple of Occupied France, get no rest. No sooner have they nailed a culprit than a telegram arrives ordering them on an all night dash across blacked out France to another crime scene. This time it is Lorient near Saint-Nazaire. These two ports were the principle bases for German U-Boats from 1940 to 1944.

The fateful telegram came directly from Admiral Karl Dönitz, nicknamed the Lion for his mighty bellows, commander in chief of the U-Boat fleet. Dönitz became head of the government for about three weeks after the death of Adolf Hitler. The telegram was odd in that he ordered them to investigate the allegations against the Dollmaker, per the title.

It is literal, the chief suspect is a dollmaker, who is also a very successful, and still living, U-Boat commander. Toy-making was a major German business for a long time and grew especially during the Weimar period to earn export income, because there were so many restrictions of German industries and shortages of material, wooden and clay toys were made. This captain has discovered deposits of very fine clay around Lorient and dreams of reinvigorating the family business when on leave between voyages.

A very unpleasant shopkeeper has been murdered on a cold and wet winter night along a railway embankment. Left it situ, Kohler and St Cyr arrive to investigate to the great annoyance of the local gendarme commander.

The nearby stones of Carnac provide the brooding presence of eternity for the nocturnal wanderers during the long black-out nights of winter. There are thousands of stones, some to rival Stonehenge.

With the death of the shopkeeper a great deal of money also seems to be missing, the money the dollmaker raised, mostly from his crew, to invest in a dollmaking enterprise with the deceased shopkeeper. Strangely though, as Kohler and St Cyr note, no one seems now to be worried about the money.

The suspects are many. It is surprising how many people were out and about on the railway embankment at the time of the murder. There is the shopkeeper’s daughter, who was probably spying on him for her crippled mother. There is a woman married to a musician who has gone silent. She may have been looking for her husband who roams the stones at all hour to listen to their music in the wind or for a lovers’ tryst. Their daughter was probably also out there, either to spy on her hated step-mother or to find her father. Then there is that gendarme commander who seems to have left footprints in the oddest places. The U-Boat captain was certainly there and readily admits it while denying the murder. Members of the U-Boat crew may also have been on the lookout to safeguard their investment.

As usual, claims to the Resistance are made both by the Germans to explain away the murder and exonerate the captain and by suspects to hide their guilt. Kohler is indifferent to these claims and St Cyr positively bristles because he has heard this plaint often used to cloak evil. To add to the brew there is at least one Jew hiding in plain sight and a young boy may have stolen the money to bribe passage to England to join De Gaulle. Or he may be dead. The Jew has no chance. The fatalism is endemic.

Around and around Kohler and St Cyr go questioning everyone, being told repeatedly not to question anyone least the morale of the U-Boat crew be undermined or the Resistance revealed. They are threatened, harassed, misled, and lied to. All typical. The U-Boat campaign is interrupted on every clear night by RAF bombing attacks, one of which nearly kills St Cyr, while members of the Resistance are preoccupied with setting differences among themselves with weapons dropped by the British during the distractions of the bombing raids.

The submarine bunkers remain in tact despite the RAF bombings.

The submarine bunkers remain in tact despite the RAF bombings.

The well known fatality rate of U-Boats is sufficient to erode morale, and the Resistance is conspicuous by its absence in the tightly controlled area around the ports. Submarine connoisseurs will realise this is the area where ‘Das Boot’ opens.

Hardened kriminologist will have no trouble spotting the villain early on, but the interest in these stories is the trip, not the arrival. Lorient is a closed military zone rather like an island and its denizens know each other well, German and French. Kohler and St Cyr peel away the layers of lies, deceptions, half-truths to arrive at a conclusion or sorts. On the one hand it is a formulaic police procedure but on the other it is a study of humanity in such inhuman circumstances. The atmosphere that Janes draws is the chief interest to this reader.

Food is scarce, fuel nonexistent, warmth but a memory, tobacco beyond price, exhaustion general, rather than fear most people, German sailors or French civilians, are numb and weary. Yet the nightmare goes on and on.

The crew of the captain’s U-Boat have no desire to return to the depths, fearing they cannot beat the odds again, but if they must to back to sea, they certainly want the dollmaker at the helm and not a new officer, ergo he cannot go the slammer even if he killed the shopkeeper.

Before becoming a full-time writer, Janes taught high school mathematics.

‘Death of an Owl’ (2016) by Paul Torday

A tragedy might be a better genre for this novel. It turns on the accidental death of an owl on a lane in the English countryside. The vehicle that struck the owl had four occupants and their reactions to the death are the centre of the book.

There is the usual backstory about the two male principals in the car; they were acquainted in their university days. The women are accorded less space though one is developed into a formidable character who has a more clear insight that either of the men. Much of the early part of the book reminded me of ‘Brideshead.’

The tragedy is that the accident leads to the downfall of the putative leader of the British Conservative Party, poised to become Prime Minister. When a character’s demise is the result of his own personality, it is tragedy, and that applies here.

Though what we readers are to make of Andrew Landford never became clear to me, and maybe it was not clear to the author either. In word and deed, until Landford became desperate beyond reason, he never put a foot wrong, yet there are hints, mostly from his one-time girlfriend that he has a dark side, the reader only sees that at the brief minutes of the death of the owl. As we see him he is sincere, forward-looking, open-minded, and the best man for the job, a Tory Tony Blair.

The story is told by one of his campaign advisors who gets caught up in first in the cover up and then the exposure. It is well written and is credible about the political machinations at Westminster as far as this reader could tell. There are some very nice portraits of other characters in this strange world.

There are some creaks in the plotting. while much is made of the police investigation into the death of the owl, it being a member of a protected species, the two women in the car at the time of the accident are not interviewed by the police. That oversight would never happen in Midsomer!

When I hesitated about the genre for this novel, one of the reasons is because the owls have mystical presence throughout. But there is a crime and a police investigation, slipshod, though it is and so I put in the krimi class.

Finally, I found the denouement with the caretakers to be deus ex machina.

Paul Torday

Paul Torday

Perhaps the simple explanation for most of my quibbles is that the novel was unfinished at the author’s death and he did not complete it, that was done by another.

I read this book more than a month ago but time and tide have kept me from writing up my thoughts until now. I chose it because of the intriguing summary on Amazon and the reference to Minerva.

‘The Eloquent Scribe’ (2016) by T. Lee Harris.

The book is a police procedural set in Pharaoh’s Egypt. There are several krimis of this ilk but ‘The Eloquent Scribe’ has a twist in the tail, namely, that the odd couple of investigators includes a cat. It may sound contrived, well it is, but in this case it works.

Sitehuti is a junior scribe still learning his cartouches. A mishap precludes a senior scribe from attending to the dictation of a High Priest. Because he is a lazy sod, Sitehuti is sent in his place to get him off his backside. Reluctantly, he goes…into another world, one of riches, dazzling scents, blinding reflections from gold and silver and mirrored bronze, a stillness that is both solemn and eerie after the cacophony of the market place that Sitehuti is accustomed to hearing, and … cats. His sense are overwhelmed by the temple.

The scribe is seated in this group from a pyramid.

The scribe is seated in this group from a pyramid.

While the priests run the temple there is one very large, very leonine cat in attendance, one Nefer-Djenou-Bastet This sacred beast instantly takes a liking to Sitehuti, and this marks him out. It is an omen that sets tongues to wagging far and wide. Given this omen, Sitehutie becomes the scribe of choice for the highest of high priests in the innermost of inner sancta.

The Egyptian Mau cat.

The Egyptian Mau cat.

That name Nefer-Djenou-Bastet is a mouthful and it quickly become Neffi.

When a messenger bearing a most secret letter disappears along with the letter, who better to find him and the letter than a man-child favoured by the gods, well, by Neffi the chief cat of the temple of Bastet? Indeed.

Sitehuti is none to sure about any of this but it beats smearing cartouches, pounding shells into ink, or scraping papyri clean for reuse, so he sets out. Slowly it dawns on him that he might have been chosen for mundane rather than divine reasons, (1) because he is an outsider and perhaps this was an inside job — so who can he trust and (2) as a lowly junior scribe he is expendable despite the favour of Neffi for who knows how long that favour will last. What Neffi gives, Neffi can take away.

What a colourful world it is in Memphis, the one in Egypt not Tennessee, and Thebes, the one in Egypt not Greece. There are Nubians, Syrians, Hittites, Caldeans, Gauvians, Babylonians, Ethiopians, and even a Phoenician or two among the Egyptians. Dancing girls, jugglers, strong men, freakish dwarfs, bear baiters, snake charmers, and…. did I mention dancing girls? Sitehuti is a normal young man.

The other pharaonic krimis I have read were, by comparison, laboured with stilted speech which I guess was meant to reflect the formalities of the time and place and packed with equally stiff social conventions which again I guess was to reflect this ancient and foreign world. They also made tedious reading.

This novel is much more salty. There are nicknames, slang, greasy food, dusty roads, sour wine, and grumbling in the ranks, with an incipient tax payers revolt against those priests who keep collecting tribute in the name of gods but those gods who never seem to deliver for the common people. The result is a lively journey.

It is a police procedural in that Sitehuti goes hither and thither asking questions and looking around gathering information, impressions, and even physical evidence while Neffi guards his back clawing off more than one thug and generally putting an aura about Sitehuti, who while grateful for the help, is not sure he likes being so special that the dancing girls venerate him at a distance rather than coming closer!

T. Lee Harris and friend

T. Lee Harris and friend

This is the first is a series with several other novels and short stories. By the way I cannot connect the title to anything in the story.

Robert Ryan, ‘A Study in Murder’ (2015)

The third in the series that I have been gulping down, one after another, ‘A Study in Murder’ once again plunges the hapless Dr John Watson, late of 221B Baker Street, into the thick of a villainous plot. Mrs Gregson is there to throw a lifeline, and the decrepit Sherlock Holmes has resources of his own to apply. The redoubtable Sie Wölfe, Ilse Brandt, continues her savage rampage. Her bodycount must have reached double figures by the end of this page-turner.

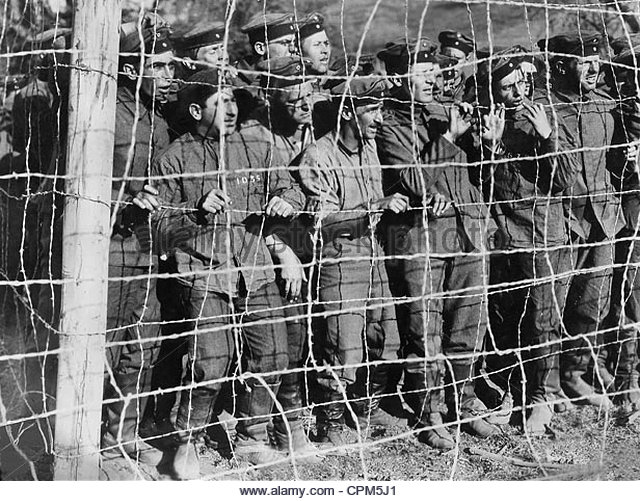

At the end of the previous volume, Watson was injured in the explosion of a tank along the Somme. He awakens to discover he has become a prisoner of war deep in the Harz Mountains. The lager is one that is hidden from the Red Cross and all manner of unsavoury things occur there. While the German regime is harsh, Watson comes to suspect the prisoners themselves are worse than the warders, English gentlemen though they may be.

The Harz Mountains

The Harz Mountains

How Watson, a geriatric, finds himself in such pickles is due to the ingenuity of the author who shows him no mercy.

Mrs (Georgina) Gregson contrives a fantastic plan to free Watson. Meanwhile, his life is made even worse by the machinations of an old enemy with a long memory who now works in German counter-intelligence. The plot is very thick. Gregson makes a tenuous alliance with Ilse, Mycroft Holmes, an MI5 man who lusts after her body, a music-hall magician, the pilot of a barrage balloon, and a cadaver. Yep. The dead can help, maybe that should have been the title here.

Holmes, they suppose, is too far gone to know or care what is happening. (Ha!)

In addition, another squad makes use of a German sniper to clinch the deal. There are many chefs in this kitchen, none with a recipe.

Meanwhile, the detective in Watson keeps following clues in the lager through cold, snow, drafts, coffins, tunnels, and hunger of the prison camp to discover…. Wheels within wheels within wheels.

POWs in world War I

POWs in world War I

For a man of his years, Watson has remarkable recuperative powers given all the stresses and strains the author deals out to him. He is struck with a rifle butt, hit over the head with timber, pushed down holes, punched in the gut, and shot, all while living on 1200 calories a day in winter, and he keeps on keeping on. What is his secret?

With each turn of the page the brew is deeper and darker, the mix is richer and more varied. There are so many incidents and characters that sometimes the book is hard to follow. It seems to be two (or more) novels plaited together.

To this reader loose ends remained, chiefly whether Captain Brevette did indeed make contact.

Ryan is a prolific writer and has turned out a nineteen novels, four in this Watson set, as listed in the Wikipedia entry. I hope he sticks with Watson for a while longer.

When I read these, the Watson that comes to my mind is that played by David Burke in the series featuring Jeremy Brett. Note that this series was split, and two actors played Watson. Burke played him as young and more physical than most do.

The quintessential Dr John H Watson of Baker Street is, of course, Nigel Bruce. His Watson is avuncular, warm, fun-loving, roly-poly, friendly as a puppy, dopey, stalwart, bluff, predictable, banal, talkative, superficial and he went a long way to restoring Watson to the Holmes cinematic canon. That is, earlier film adaptations of Holmes stories had diminished and sometimes omitted Watson. By the way the ‘H’ stands for Hamish.

Nigel Bruce

Nigel Bruce

Moreover, Bruce’s Watson also represented the perfect foil for the quintessential Sherlock Holmes, Basil Rathbone. This Holmes is mercurial, incisive, cloaked, impatient, spare even sour, mince, cryptic uncommunicative, mysterious, and razor sharp. They partnered in fourteen films, ending only when the executive producer died, leaving no one else to champion the franchise, which in truth was tiring. The directing and acting had remained pitch perfect, but the stories, despite the oeuvre available, had became hackneyed in the effort to give them contemporary settings in the 1940s.

Nigel Bruce was the second son of a baron. But he was stage-struck as a youth and foreswore the life of the landed gentry for the theatre. He was an infantry officer in the Great War and suffered eleven gunshot wounds at Cambrai (Northern France) in November 1917. Those wounds ended any later army career. By the way, British tanks were deployed in this battle but in dribs and drabs as mobile block houses, not as a strike force.

I met Basil Rathbone at a poetry reading and I was an undergraduate in 1966.

Robert Ryan, ‘The Sign of Fear’ (2016)

Once again Dr John Watson, a serving major in the Royal Army Medical Corps, is thrust, unwillingly, into action. This time the setting is London, a London that is under siege in 1917.

Everything is in short supply — food, medicine, clothes, manpower — as the U-Boat stranglehold tightens, cutting off supplies of everything.

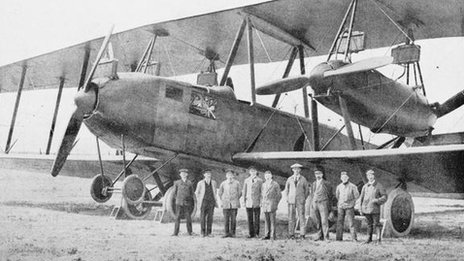

Moreover, the city is being bombed, first by Zeppelins, but when they proved too fragile and hard to handle, there was a technology leap to the long range bomber, Gothas and Giants. These aircraft operated from Belgium. They flew higher than the rudimentary anti-aircraft guns could reach, and higher than the Royal Flying Corps pursuit planes could climb, and so the bombers came day and night when the weather permitted.

The Zeppelin were so unreliable that at least one raid bombed Hull in the belief it was London. Consult a map to see the magnitude of the navigational error.

A Zeppelin over London.

A Zeppelin over London.

Meanwhile, the privations killed the weak and vulnerable, sapped the energy of all, and depressed many. The bombs were few by subsequent standards, but they terrified one and all and paralysed the populace far beyond their destructive power. Per Wikipedia there were eighty air raids and add to that the false alarms.

It was the world of war that H. G. Wells had imagined, waged by machine. This bombing experience goes a good way to explaining the focus on airpower in the inter-war period.

In such a brew there were rumours of still other weapons to come, like canisters to drop poison gas or diseases, like giant cannons to bombard England from the continent, like …. As always these wild speculations were promoted by the press.

Amid all of this hysteria, Dr Watson finds himself drawn into a terrible nexus. There are anti-conscription plotters, the incipient Irish Republican Army, and German spies and saboteurs, along with criminals, each hard and work and perhaps in some kind of alliance. Added to that are the machinations of MI5, as the counter-intelligence agency, which seems even more sinister, if polite and civil in person. The defence of the realm (DORA) seems to justify anything and everything.

Then it gets worse. All members of an important war committee go missing in one night! Watson, as his luck would have it, is the last person to have seen one of them…alive.

Once again Watson is battered and bruised, and barely able to walk, but walk he does: into another trap. He even takes to the air in more than one way.

Ryan’s evocation of 1917 London under siege is very well done, and much of it an eye-opener to this reader, leading me to consult many Wikipedia entries for a start I had always thought that the bombing in the Great War was a few explosives dropped by wandering Zeppelins. There was much more to it.

There are many loose ends in this title, as with the earlier ones. It is by no means clear to this reader that the plotters were working alone or in tandem, the death of Ilse Brandt is muddled, why was the captain arrested at the end, did Watson land safely or not… While the opening haste is explained at the end, it begs one principal question, why did that captain allow the nurse on board if he knew what was to happen, and if he did not, why was he culpable.

It ends abruptly as though time was called not because resolution had been achieved.

In 1917 with its own resources, including civilian morale, wearing down, despite the closure of the Eastern Front, the German war cabinet gambled on a throw of the dice to drive England to the table before the United States entered the war.* The conclusion had been reached in Berlin that the United States would sooner rather than later enter the war on the British side. To preempt that entrance, the decision was to do everything possible to drive Britain to terms, if not surrender. Seeing no way to break the stalemate on the Western Front, other fronts had to be enhanced: espionage, and the sea and the air.

The chief result of this decision was the official declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare. No ship would be safe, neutral, unarmed, far away, or bearing Red Cross markings, all would be targets. The calculus was that a denial of supplies would starve England into submission before the Yanks arrived.

This much can be found in most detailed histories of the conflict. As often is the case the direction of casual arrows is by no means clear, because the advent of explicit and authorised unrestricted submarine attacks is the very matter that prompted President Woodrow Wilson’s reluctant move to war and convinced and the even more reluctant Congress to concur. One could say that the German decision produced the very result it had been intended to avert.

What was new to me was the accompanying bombing campaign which was partly aimed at the shipping infrastructure on the docklands, but since the accuracy of the attacks was, well, there was no accuracy, and so the effective target was the city of London, though other ports like Southampton were also hit, sometimes by accident or mistake as Hull above.

In both submarines and bombers, the Germans had for a time technical superiority over the counter-measures.

One of about eighty Giant bombers that operated from Belgium against England.

One of about eighty Giant bombers that operated from Belgium against England.

England was the target of the bombers rather than France because the Berlin assessment was that aiding the French would not motivate public or political opinion in the United States, and if Britain could be subdued, France would follow, one way or another. Also France was much less dependent on shipping for food.

*The Eastern Front did close with the Communist coup d’état in Russia and the peace with the Soviet Union, but the turmoil there was great and continued, many, many German and Austrian troops remained engaged there in Poland, Finland, and Rumania, in particular, as warring elements battled for spoils.

‘Madrigal’ (1999) by J. Robert Janes

They are at it again, Inspector Hermann Kohler and Chief Inspector Jean-Louis St-Cyr, an odd couple of Occupied France, in another atmospheric outing.

These two are routinely dispatched where angels fear to tread, each with the scars to prove it.

It is a very cold winter in January 1943 and the screws are tightening.

While Kohler carries a card that says Gestapo on it, he is on the lowest rung of that feared and fearsome organisation in Kripo. The Gestapo has many other branches including the feared Sipo, Sicherheitspolizei, or security police which are much more important. Kripo is short for Kriminalpolizei and Gestapo is short for Geheime Staatspolizei, Kripo investigates crimes, period.

In a criminal world, we might say Kripo is devoted to civilian crimes, rape, murder, larceny, and other felonies.

State run genocide, slaughter, torture, slavery, systematic theft on a national scale, these are the norm in this world.

St.-Cyr outranks Kohler as a chief inspector of the Sûreté National from Paris. However, in the arrangement of the Occupation Kohler has charge of weapons and much else.

These two were thrown together in the first title in the series, which now runs to seventeen volumes. The first was ‘Mayhem’ (1992) and this is the tenth. They are now well acquainted.

The niceties of Occupied, Forbidden Zone, and Unoccupied — Vichy — France have collapsed with the Allied landings in North Africa. The pretence that Vichy was a sovereign neutral is exploded.

A young woman associated with a cathedral choir has been murdered and this duo, who have learned a lot about each other over their collaboration, is sent to clear it up.

As always there are wheels within wheels within wheels within wheels. While Kohler and St Cyr trust each other, they do not trust their superiors who send them here and there, sometimes in the hope that they will fail. They meet obstruction at every turn.

Anticipating an Allied invasion in southern France, the Wehrmacht has no use for outsiders while it prepares for an invasion. The local Vichy authorities want to run the show, if no other reason than to prove their loyalty to the regime and its sponsor, and they attribute the murder to terrorists of the resistance to justify further arrests to bump up their key performance indicators. Other branches of the Gestapo would be rid of these two busybodies but for the protection of the chief in Paris. Louis’s superior offers no protection whatever. Most of this obstruction is reflex, ‘Non’ is the easiest word.

But some, or all, of the obstruction in this case might be material. Who can say without investigation?

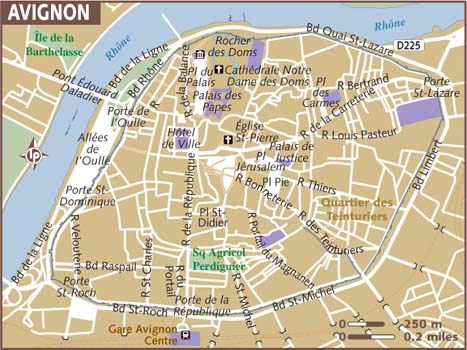

They are down south in Avignon where the winter Mistral seems to come straight from the Russian front. Between 1309 and 1377 Avignon was the centre of the Christian world because a succession of popes resided there, and it remained under the control of the Papacy as a papal state until 1791 long after the Holy See returned to Rome. Only the French Revolution made it French, again.

The line of the wall is visible in this contemporary map.

The line of the wall is visible in this contemporary map.

Added to the murder is the ambition of the sitting Bishop in Avignon to see the return of the Pope to Avignon. Crazy? Maybe, but it is a crazy world where genocide is normal and purse-snatching is a crime. With the slow collapse of Mussolini’s regime, perhaps the Pope might leave Rome or be evacuated by the Germans as a prize for ransom or some such. Is it a coincidence that the music master of the cathedral is an Italian from Nice? Before Napoleon, Nice was Nizza, an Italian city and it was claimed as such in 1940 by the Italian ally of Germany.

If the Pope leaves Rome where better to go than the Palais des Papes to drink Châteauneuf-du-Pape in Avignon.

Le Palais des Papes as it is today.

Le Palais des Papes as it is today.

The scandal of this murder in the cathedral could likely spoil this hope. Better to keep it all quiet.

Then as now Avignon is a world to itself, preserving to this day its medieval ramparts that cut off the ancient core of the city from the rest of the world. The cathedral sits at the very centre of this rock world. And within it the madrigal singers are a protected species who want no intrusions. Non!

Around and around Kohler and St Cyr go questioning everyone, being told repeatedly not to question anyone least the superficial tranquility be disturbed. Yet head office in Paris demands resolution. They are threatened, harassed, misled, and lied to. All typical.

Tranquility indeed, as the Milice scours the town for Jews, the Germans rake the hills for Maques, Vichy officials steal hidden food, the Churchmen flagellate themselves and each other, and the Nuns get up to their own worship. What a concoction this is.

It is a nice touch that in this crazy world, the sanest man they meet in Avignon is the German commandant.

Janes conveys the exhaustion, the dreariness, the hunger, the bitter cold of unheated rooms, the fatigue, the gnawing suspicion, the darkness of a world where the German vampire has sucked everything out of France and the French to fed the maw of the Russian Front. (And also Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, and more.)

As a prisoner of war St Cyr learned German. His wounds precluded further military service in 1939, as did Kohler’s wounds. He, too, had been a prisoner of war and learned French in captivity. Both in the Great War, the war to end all wars, World War I.

St Cyr’s wife and only child were killed by a booby trap; it might have been set by either the Maques or by the Milice. It may have been intended for him. Kohler’s two sons died on the Steppes. His wife long ago gave up life as a policeman’s frau.

Their only loyalty is to each other, and that has been forged in the pursuit of the guilty no matter who or what. They will find out who done it, no matter what. What happens then is up to higher powers at headquarters.

There are times when the reader must be patient. Dialogue marked with quotation marks is often preceded or succeeded by thoughts, and it is not always clear to this reader whose thoughts they are since only rarely does Janes honour the convention of adding ‘Kohler said’ or ‘St Cyr thought.’

Nor are these signposts always used when they speak to others, there are strings of dialogue without an indication of who is the speaker of which lines. Sometimes it is clear which voice is whose, but not always, and that is when the guesswork and errors set in. I write as a maker of guesses and the errors.

While quibbling over minutiae I add that the word choice is at times numbingly repetitive. People speak softly a lot and close doors softly. Softly, softly, softly. Get a thesaurus and try quietly, low, delicately, smoothly, tenderly, faintly, gradually, gently, and more.

Generally, the characters are distinguished in their manner of speech. That is an uncommon achievement. All hail.

J. Robert Janes

J. Robert Janes

Each title in the series is one word and I like the clarity and audacity of that, e.g., ‘Gypsy’ (1997), ‘Salamander’ I1994), or ‘Tapestry’ (2013). There is a complete list of his novels on Wikipedia.

‘The Dead can Wait’ (2014) by Robert Ryan

The second entry in the series featuring Dr John Watson, once of 221B Baker Street, and now serving in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) during World War I. Watson is over fifty but in the crisis the RAMC welcomes his service. Even older and more infirm, Homes is left to keeping bees on the South Downs.

Watson’s celebrity as Holmes’s amanuensis opens many doors for Watson, ironically, sometimes he would prefer that it did not. Winston Churchill is one of his admirers and he soon makes Watson a pawn in a deadly game. Churchill recruits Watson for a mission in the heart of darkest Norfolk to find out what is bedevilling a weapons development project located there. The title refers to the soldiers killed there in an inexplicable accident.

Churchill’s method of recruitment is coercive, both physically and morally. Special Branch muscles Watson and there are none too subtle threats made against the decrepit Holmes. When Churchill wants something, nothing is left to chance. ‘No’ is not an alternative.

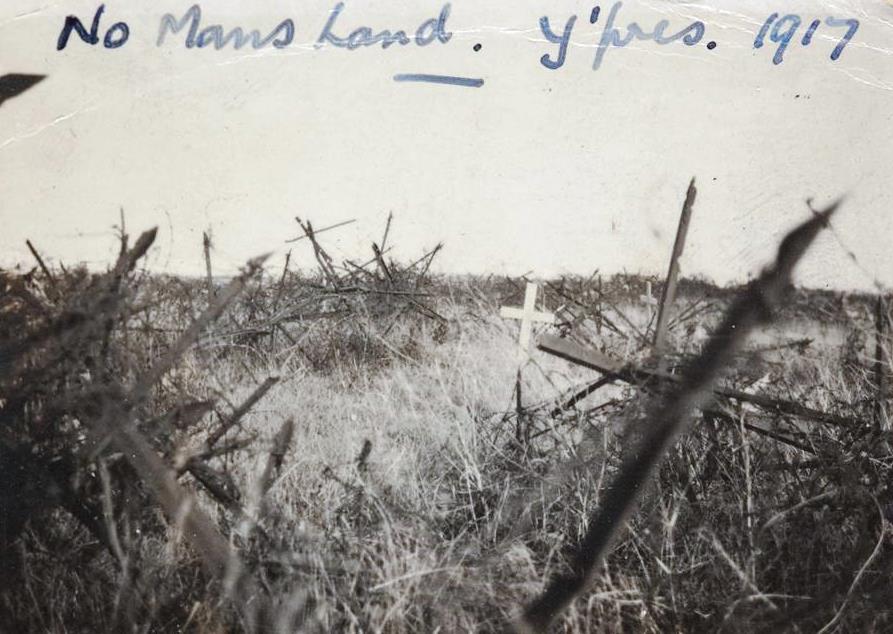

It is 1916 and trench warfare is a reality. The death tolls on the Western Front are astronomical. In the first title in the series Watson spent some time at Ypres, and knows all too well of the mud, the lice, the stench, the shelling, the rot, the dread, the pointless slaughter, the disease, the maimed, the gas…. While the physician within him wants no part of weapons, new or old, the man within wants the blood orgy to end. Reluctantly and with bad grace he agrees to investigate.

Dilbert could tell him the truth, incompetence, empire-building, blind corporate rhetoric, can-do mentality unchecked by reality, these all too often combine in a cocktail that doom all the most robust of projects. However, this is a krimi and villains there must be and they are aplenty.

To explain by a comparison, in the 1970s we now know that there were more police informers and double agents in the Front de libération du Québec than firebrand radicals, that most of the money the FLQ used for guns and explosives came through these agentsfrom the Sûreté du Québec, that that these provocateurs expressed the most enthusiasm for blood, and so on. Different sections of the Sûreté infiltrated and kept it secret from other sections so they worked at cross purposes. Much is the same here. There are so many spies in and around the weapons development project that they crowd out the technicians.

Watson does not have to play a lone hand. Mrs Gregson of the Volunteer Aid Detachment (VAD) whom he met in the first book, ‘Dead Man’s Land,’ is there with her flaming red hair, suffragette attitudes, and her extensive knowledge of motorcycles learned with her three brothers as a girl. She also knows how to defend herself thanks to those brothers. Most of the members of VAD worked as medics or nurses but did not have the formal qualifications of those professions. Mrs. Gregson, whose first name has not yet been revealed, drove ambulances in addition to clinical duties. She is a long way from the Edwardian norm for a lady of her social class. Smart, ambitions, opinionated, vocal, mechanical, uninhibited, and since she is a suffragette she is also a threat to the realm as men know it, altogether a tonic.

Watson and Gregson are united by the threat of DORA. When that name is spoken, a dark mist descends. There is no appeal from DORA. There is no higher authority than DORA. Once engaged DORA grinds all into dust.

DORA is a what, not a whom: the Defence of the Realm Act. When invoked this act enables search and seizure without warrant, incarceration without habeas corpus, no due process, or anything else. No test of rationality is applied. When Churchill invokes DORA… The likes of Watson and Gregson have no choice, or do they?

Against his will, Watson finds himself on the Western Front again and there is no safe place there.

Read the book to find out. As homework, consult Max Weber on bounded rationality.

I came across this passage from Primo Levi when looking for graphics. It is not referred to in this text but perhaps it should be.

It is true that Churchill was instrumental in the development of the tank, along with many other weapons and the Royal Flying Corps. As minister of munitions he sponsored a multitude of experiments to find the means to break the deadlock on the Western Front, keep Russia in the war, and defeat Germany. One such project involved ‘mobile water tanks for the Russian army.’ Hence the heavy gauge sheet metal, the welding, the reinforced plates, all were ostensibly for water tanks. That was the code name for project.

It is also true that Churchill spent months at Ypres in the trenches and went on more than one night reconnaissance across no man’s land to find German snipers and take prisoners. He knew trench warfare through his skin, nose, eyes, ears, and taste.

Robert Ryan has complete command of the period detail and the subject matter. Moreover, he breathes life into both the time and the place. When I compare this novel to a couple of others I have read recently by the celebrated authors, Umberto Eco (‘Número Zero’) and Yann Martel (‘The High Mountains of Portugal’), well, there is no comparison. Ryan’s book is full of life and colour whereas the two by these literary festival luminaries are dreary recitations that read like pastiches of Wikipedia entries.

Ryan’s novel also has a plot which distinguishes it from the novels of Eco and Martel named above.

There is a ‘but’ or two. The dish is too rich. There are so many side dishes, that the main course is lost at times when we delve into Zeppelin navigators, she-wolf training, rations for hostelries, Edwardian dental techniques, and so on. There is a very great of cutting back and forth which this reader never likes, still less when it is not signalled and there are so many ephemeral characters who are introduced, fleshed out, animated, and then dispatched. I plead for more economy and focus, though that always exposes the plot-holes all the more and there are a few here.

There are also a surprising number of typographical errors. The most jarring are the times when Watson things to himself about something and the text has it as ‘Holmes.’ For example, Watson picks up an object and thinks to himself, now ‘Holmes what the blazes is this doing here.’ Huh. No I do not think it is intentional to show the merging of the one, Watson, into the other ‘Holmes’ since it is not sustained. There are a few ‘form’ for ‘from’ and some errant prepositions.

My guess is that Ryan has spent a lot of thought and effort at imbibing the Edwardian Era, the Holmes Canon, the horrors of the Western Front, England in the war, and the war in general from armies to zeppelins and all the letters between. He wears the knowledge lightly, for there are no forced recitations of material, but rather he uses it deftly to enrich the action.

The Holmes Canon is a crowded field with all manner of — what should they be called — continuators? contributors? canonistas? There are those writers who simply re-animate Holmes and continue the stories. Some go to the young Holmes or to his mentor(s) or his brother Mycroft. Others with an orthogonal rotation, place other figures in the centre, like Mrs. Hudson, or who give Holmes a wife, the marvellous Mary Russell in Laurie B. King’s series, or the Baker Street irregulars. There are others that centre on Watson apart the series at hand. Even Professor Moriarty has been rehabilitated in the imagination of at least one author. Of those which I have read, some succeed in their own terms, like Graham More’s ‘The Sherlockian’ (2012), but more often than not they do not. Most try too hard to compensate with period detail, plot twists, or adolescent humour for the twin lack of insight and imagination. These are the canon fodder.

The outstanding example of failure is the BBC television series with Benedict Cumberbatch which started brilliantly in the first three episodes and, then, gradually descended into itself. The writers ran out of ideas and let the Computer Generated Images take over to milk the success of the first tranche. Being incomprehensible became its style without substance. Adolescent, indeed. Very successful it has been, I believe, but we lost interest long ago.

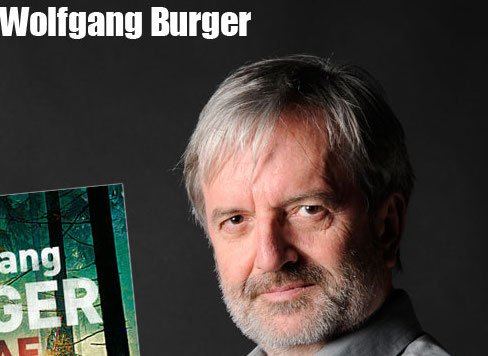

‘Heidelberg Requiem’ (2016) by Wolfgang Burger

This is the first title in a series of ‘gritty crime novels,’ as proclaimed the blurb on Amazon Kindle. Heidelberg, that is the city where Georg Hegel once held forth. No nerd could resist that.

The set up is this. The Chief Inspector Alexander Gerlach is moving to a new more senior position in Heidelberg from Karlsruhe on the Rhine with his two teenage daughters. The move is a promotion with an accompanying increase in pay, but more importantly it also leaves behind the sad memories of the death of the wife and mother in Karlsruhe.

The book opens with a reception in the town hall where the new Chief of Detectives is introduced to the community leaders and the local media with whom he will be working, meeting, lobbying, and interacting. Our hero has some qualms about the whole business for while he needs the money and wants a new start, he is aware that his experience and aptitude for the new job are ….. not outstanding.

No sooner does he enter the office the next day than the corpses start appearing. There follows some travelogue in the city, but it reads like a guidebook by the numbers without texture. Heidelberg could be Anywheresville. Red herrings are pursued and more than once our hero is sure he has his man. Only to be proven wrong. Mistakes do not deter him and he repeats them several times. When subordinates urge caution, he rebukes them.

The Police Commissioner is pretty cross with him, because the protagonist insists on doing the field work himself rather than assigning and supervising others. Indeed.

The Police Commissioner is right. The job is to manage, organise, and lead, not peer through keyholes but peer through them he does. The Commissioner is also right in a second way. This protagonist is naive beyond credibility. He takes everything at face value.

When a drug user acts guilty, that’s it; he’s guilty; bang him up. When a woman throws herself at him, he accepts it as his due. When his daughters say they will be home by 10 pm, he is satisfied.

It does not occur to him that the drug user has much to be guilty of apart from the murder(s). That the woman is up to something. That his daughters say that to get him off the telephone, not as a commitment.

His conduct of office violates most ethic codes. He uses uniformed police in patrol cars to ferry his daughters around. He has his secretary look after relations with the new school for the daughters when she is not fetching him coffee. He uses police resources to get himself settled in the new digs. In fact, his abuse of office, though small potatoes, mirrors that of one of the suspects who seems to be defrauding a charity by using its resources for his own entertainment.

His inattention to his thirteen year old twin girls is also hard to swallow. There are many scenes with them, yes. But more often then than not, he sends them on their way, forgets to pick them up, lets them stay out all hours…

The plot does tie up the loose ends, though it is mostly off-camera since the villain is not in sight for most of the book. His pursuit though takes the bulk of the book but most of it is not described. In fact, there is little policing in this police procedural. However, the invisible man was well done. The janitor is someone no one notices, either when he is there or when he is not. That was a nice touch.

The only interesting character is his disappointed rival for the job, who is clearly far more qualified, both as an investigator and as a manager. She did not get the job, as she says, because she is a woman; and that seems to be so. Having a Greek name is also a second strike against her.

The protagonist is indeed in well over his head. He got the job over more qualified candidates because the Commissioner’s wife insisted on his appointment because she liked the naiveté of his application! She thought it was so open, so natural, so…

Is this how senior appointments are made in Germany! Too silly to believe. Angela Merkel, get on to that!

‘Gritty,’ I hesitated when I quoted that word at the outset. When a thriller is trumpeted as ‘gritty’ I usually pass, having found that this word often signals an anatomical detail of violence. Not so here. The only grit I noticed was the squalor of some of the drug users.

That Chief Inspector Gerlach misuses the resources of his public office for private needs does not seem to be noted. Still less the parallels it offers to the charity thefts. Nor is it clear that his off-again on-gain parenting is any concern to the Office of Child Protection, but it probably should be. Finally, there no resolution to his role as supervisor rather than keyhole snooper.

Now perhaps some of the oddities mentioned above will be smoothed over in subsequent titles, but I will likely never know.

‘Dead Man’s Land’ (2013) by Robert Ryan

Against the advice of his dear friend and mentor Sherlock Holmes, Dr John Watson volunteers for the British Army in 1915. Though he is over fifty, the Royal Medical Corps needs every qualified physician it can get, and he is soon in uniform and posted to Belgium.

That is the premiss.

Watson is assigned the task of teaching field surgeons a new technique of blood transfusion, and this mission takes him here and there near the front lines because it is there that blood transfusion can do the most good.

Amid the squalor, death, and destruction of trench warfare at Ypres, he notices a death that seems odd. At first the suspicion is that the new method of transfusion is to blame, but that conclusion is soon dispelled. Then there is another murder.

The army medics are so swamped and exhausted by the maimed, wounded, and dying that they have no time, energy, or wit left over for anything else. Moreover, they are assigned to one place. By contrast, Watson has some freedom of movement and some repose to think about what he has seen.

He starts to make inquiries and …. He forms a shaky alliance with an outspoken suffragette nurse’s aid, and bluffs his way here and there with his rank of major, with his fame at Holmes’s chronicler, and with his assured manner. His suffragette ally also plays some cards of her own and from their investigations a pattern begins to emerge.

Among the thousands and thousands of deaths that go through Clearing Station Five in the sector, five or six have not been the result of warfare. accident, or disease. They have been murdered. There is a murderer at work within the ranks!

Whatever for amid such a charnel house, Watson asks? Why bother when every man at the front will probably die soon enough? Yet the murderer pursues his victims even in extremis. What is the pattern and who might be next!

The set-up is a fresh take on the Holmes canon, and Holmes himself figures in the story with an apprentice. This Watson is persistent, insistent, and nobody’s fool but neither is he Holmes, as he realises.

But the Military Policemen are solely preoccupied with deserters and infiltrators and place no faith in the story he tells. He is after all a teller of stories, is he not? An over-active imagination set off by the shock of the front, they conclude. He is shown the door.

He will have to do it all himself.

There is an array of characters and a volume of detail about trench warfare. A counterpoint is offered in the role of German sniper who proves…. Winston Churchill is there in the trenches and gives Watson a hand.

Churchill at Ypres

Churchill at Ypres

Altogether a compelling story well told, though the gruesome reality of the Ypres salient was taxing to read. There is even some gallows humour.

Robert Ryan

Robert Ryan

This is part of series and I intend to read other titles in it.