Honolulu in 1934 is the setting. The British Museum lends a rare Hawaiian painting to the Bishop Museum and a curator accompanies it, himself part Samoan. There he meets a feisty woman reporter and they team-up.

Why?

Because the painting is stolen from the Bishop Museum during the gala reception on New Year’s Eve. But wait! There is more. The very unpleasant and unpopular director of the museum has been murdered.

Are the two crime connected? Apparently not, yet the coincidence is unlikely.

And later a third, historic crime comes to light which is related to the stolen portrait.

There is some to’ing and fro’ing in pre-war Honolulu and Waikiki along Ala Moana, the Pink Palace, and Lei’Ahi (Diamond Head to Haoles).

In the small world of 1934 Honolulu nearly all of the persons of interest are taking part in an amateur play and the curator and his gal-pal are, too. Just by chance the curator, in his spare time, is the playwright.

The time is right but there is no Charlie Chan in sight. Nor is there any mention of the sizeable military population at Pearl Ridge, Pearl Town, and Pearl Harbor. For the cognoscenti, Doris Duke began to build Shangri-la in 1936.

The dialog distinguishes the characters and the comments on the tropical flora and fauna are measured, enough to evoke but not so much as to labor. However, the pace is slow and the family’s relations are hard for this reader to grasp. But there is much description for its own sake, neither deepening the context nor integrated with the plot, i.e., clothes, room furnishings, store fronts, and food. As a result the pace is s l o w.

There is a satisfying array of suspects and much back-and-forth. Every scene is wordy. The author is a playwright and there is much, too much, dialogue from ordering coffee to the weather. I was hoping for more of the Bishop Museum, but despite its importance in the plot there was little compared to all the other description. Too bad, Bishop is one of our favourite places while on Oahu.

While philately provides a material incentive for a villain there is little about why the stamps in question are so valuable, compared to the many descriptions of decor. Note, a philatelist does not cut stamps off envelopes. Too crude.

Victoria Nalani Kneubuhl

Victoria Nalani Kneubuhl

First in a series but not sure I want to press on.

I have been stockpiling Hawaiian krimis since our last visit in 2010. There are many set in Hawaii and my collection is modest.

Category: Krimi

‘Remember the Scorpion’ (2015) by Isaac Goldemberg

A police procedural set in Lima, the one in Peru, in 1970. The protagonist smokes opium and snorts cocaine amid the rubble left by an earthquake. Somewhere the Peruvian socccor team is winning and that alleviates a little of the pain of the destruction for some.

Detective Captain Simòn Weiss is Jewish and makes sure everyone knows it, accompanied by a half-Japanese Lieutenant Kato, like the Green Hornet’s off-sider.

The narcotic haze lifts a little and there are two murders. One isa Japanese crucified on a pool table. The other is the faked suicide of a Jew.

Many shades of World War II haunt Lima. Jews fleeing Naziism found their way to Peru, and after 1945 so did some Nazis fleeing nemesis. Then there are some Japanese war criminals hiding among the local Japanese community, some of whom were deported to camps Stateside, it says in these pages, during WWII. Whew! This plot is thick.

Weiss spends a lot of time worrying about his love life, his mother, his step-father, his mystical dreams about a scorpion, his long-term girlfriend, until he is swept off his feet by a pretty face who promptly dumps him. He is as smitten as the heroine in any bodice ripper at the sight of manly pecs.

Meanwhile, he and Kato tote up a multicultural body count of villains, Japanese and German, and Peruvian or two for good measure.

In part the story is high romance as Weiss meets the girl of his dreams. Remember the opium?

There is no policing to speak of. Everyone knows everyone else and the coppers follow their noses to blast the villains. The formulaic confrontation with kowtowing superiors are only half-hearted.

After slaying the dragons and losing the damsel, Weiss rides off into the sunset leaving Kato to take the credit. That would seem to mean that there will be no future adventures of gunslinger Weiss. West from Peru is a wet ride.

That the hanged man somehow managed to slip a note into the ceiling beam to identify his murders might seem a little far fetched to some.

That Weiss thinks mainly about himself might bore some readers.

That there is little about either Peru in general or Lima particular may disappoint some readers. Though some of the references like to the military school with its yellow walls reminded me of a Mario Vargas Llosa novel, ‘The Time of the Hero.’ Llosa is The Peruvian writer, despite his longtime residence in London, to me. I also read his ‘War at the End of the World’ and found the descriptions of Gaugin’s painting in ‘The Way to Paradise’ to be more compelling than any other of his work I read.

Isaac Goldemberg

Isaac Goldemberg

The book has a forward in which a friend lauds the genius of the author and an afterward lauding the genius of the translator. Never a good sign when someone else has to try to convince the reader to read the book.

I first encountered this book with its exotic locale in a bookstore in Helsinki Finland in September 2016 and it was only later that I read it on the Kindle.

‘Pel and the Perfect Partner’ (1999) Juliet Hebden

The adventures of Chief Inspector Pel of the many names continue.

Pel goes missing between home and office. Madame Pel, used to his erratic hours, patiently waits, while at the office the ever loyal Darcy is so preoccupied with his love life, for this Lothario is madly in love with a woman who is out of reach geographically and perhaps socially, that he cannot think of anything else, so he does not notice Pel’s absence for several hours.

Then Madame Pel telephones Darcy and the alarm bells rings. Pel has a long list of enemies, krims he has banged up, and the worst is feared. Meanwhile all leave is cancelled, Sergeant Misset whinges on cue, and no stone is left unturned. Until….

In a strange phone call Pel tells Madame Pel to instruct Darcy to stop the search.

Odder still.

Two days later Pel reappears none the worse for wear with a strange story to tell. The gist of it is that an old nemesis wants Pel to find his missing granddaughter and in return the nemesis will go quietly.

It takes Pel far too long to find the girl whom he keeps tripping over without recognition but there are compensations in the old, garlic eating baron who is much quicker on the uptake than his dithering manner suggests, in de Troq’s capacity nearly to read Pel’s mind in a crisis, and in the balanced portrayal of the gung-ho special team brought from Paris. Nice for once to find a fictional police officer who is a person not a stereotype.

While the situations in these books are stereotypical, the handling of them is not. The baron has ability that belies his appearance. The head of the SWAT from Paris listens to reason and has no desire to go in shooting if it can possibly be avoided. In a TV cop show these two would be reduced to cardboard.

Much to Pel’s surprise it all works out, for he the eternal pessimist expected the worst, and his nemesis even keeps his word, which Pel did not expect. But not quite in the way he was supposed to do. Yes, he surrendered but he did not give up.

Cannot figure it out? Read the book.

Juliet Hebden

Juliet Hebden

This was my reading on QF3 Sydney to Honolulu in March 2017.

Umberto Eco, Número Zero (2015)

I was intrigued by the cover that referred to the escape of Mussolini. Francis Deakin in ‘The Brutal Friendship,’ a study of the relationship of Mussolini and Hitler, made him seem, in part, an Italian patriot. What would Eco make of him, I wondered. The blurb emphasised the thriller of Mussolini’s escape.

But….it takes forever to get to Mussolini, a quarter to the book or more, and then that part disappears.

This is the conceit. A nameless millionaire wants to start a newspaper. He hires a team of surplus journalists to do a proof of concept. They are to prepare dummy, uncirculated editions for a year. These specimens will be used to solicit other investors. Who knows, maybe that is the usual practice. None of the team, all writers and editors, know anything about the business side of publishing.

But some of the team are cynical enough to suppose that the dirt they put into the dummy editions might be used for blackmail.

There follows page after page about the media, its evils and manipulation. This lecture is relieved only by a travelogue through the streets of Milan. Oh hum. Not what it says on the back cover. Not why I bought it.

Then one of the journalists comes up with the story of a body double for Mussolini who was substituted for the real man. This is a discovery that is unrelated to the foregoing. It just pops out.

For this reader the book I bought starts there. Knowing nothing about these final days of the Fascist Regime, I found it a plausible speculation. The nub is this. While Mussolini’s face was known to millions through ubiquitous photographs, films, statues, postage stamps, coins, and more, few ever saw him up close in the flesh for more than a second or two apart from the inner circle.

Now add that he had a body double to foil assassinations and to do the boring duty of watching parades. This man might have a considerable resemblance and been at it so long that he came to think of himself as a Mussolini. He would be known to the inner circle.

Add the wear and tear of the last months and years, weight loss, ulcers, narrow escapes, worry, stress and Mussolini’s physical appearance and mental balance would have been altered as well as that of his doppelgänger.

Finally much confusion as the last Fascists flee from the Italian partisans, hoping either to surrender to the Allies, but then they did not go south where the Allies were, or to make it north either to Switzerland or Germany.

Why escape? One, to save his life and perhaps to fight again another day. If Mussolini survived perhaps he could help others in the inner circle and their families. Perhaps a living Mussolini could negotiate for Italy. Perhaps a living Mussolini could be used against the prospect of a communist insurrection in Italy. Once the speculation starts, it has no end. All of this is interesting but there is very little of it, and it is only just that, speculation. None of it is fleshed out.

Much more interesting than another media diatribe or a streetscape of a corner of Milan. Though there are more lectures on the corruption of the media sprinkled throughout. Oh hum.

The Mussolini part disappears from the last third of the book in favour of more recitation of media evils and Italian corruption. Old news not particularly well told. Along the way are some obligatory sex scenes which the author is very poor at rendering. Must have been included to please an editor.

The Número Zero of the title has nothing to do with Mussolini, but is the first edition of the mock newspaper.

In sum: a major disappointment.

I once drove Signor Eco across the Harbour Bridge when he visited Sydney.

‘The High Mountains of Portugal’ (2013) by Yann Martel

Having been reading about Portugal, I tried this title.

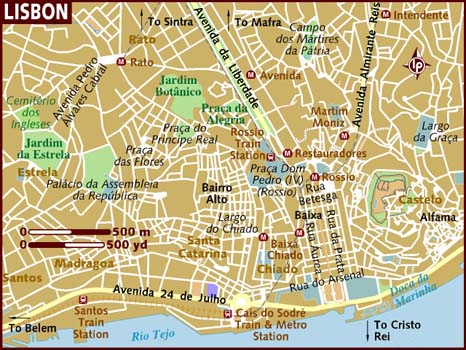

It opens with a nice walk through 1903 Lisbon. I followed some of it on Google maps.

However this book is SO contrived. Our protagonist walks through the city backward, yes like a defensive safety or like Ginger Rodgers! He is sad and in mourning and expresses it in this way and has been doing this for a year or more. Oh hum. Thus making others responsible for not colliding with him. How egotistical. Out of my way! Coming through, backward! Yes I know walking backward can be a form of contrition but there is none of the spiritual depth of that implied in these pages, where it reads like what it is, a gimmick.

The backward walker reaches his rich uncle’s house and uncle is a lively character who wants to move with the times, in particular with the automobile. Many pages are consumed as the uncle tries to explain to the protagonist how to drive. He makes no effort to learn but some how does manage to do it. Backward, indeed.

He then drives off to the high mountains on a quest. To find an altar piece carved in Angola and which is in a little out-of-the-way church there. He read about the altar piece in a priest’s diary from the 16th century, which no one else has read, it having been buried in an uncatalogued box in the national archives, and then traced it through shipping, archival, and ecclesiastical records. That part was interesting but sped through.

Nothing compelling here. He manages to drive the car through villages to the amazement of locals and the boredom of this reader. It is a short book so I will flip more, but…

I did keep flipping. It is three stories connected only by the author’s assertion that they connect. After the motorist who does find the altar piece, which portrays Jesus on the cross as an ape. Better if it were an African slave after the harrowing descriptions of that.

Then a doctor and his wife in 1938 without any reference to the Salazar regime or the wider world that I noted in my FF, Fast Flipping.

Then in the 1980s a Canadian senator who retires there. Odd that. The author does seem to know anything about the Canadian Senate which is largely ceremonial. While the senator’s ancestors were Portuguese he hasn’t the language but moves there anyway in retirement with his recently acquired pet ape. Yep! The first scene of recognition with Odo, the ape, is very good, but then it is repeated with dogs, with birds, Odo can relate to anything.

Once again it seems to me that all this creativity is to impress other writers, awards panel members, and jaded reviewers and not to entertain, educate, or stimulate readers. Moreover, most of it seems to have been researched in manuals and reads like it, the car, the mountains, the apes; it reads like digests from Wikipedia interspersed with some dialogue and a few quite good scenes.

Even more depressing than reading the book is reading the high praise heaped on it by professional reviewers.

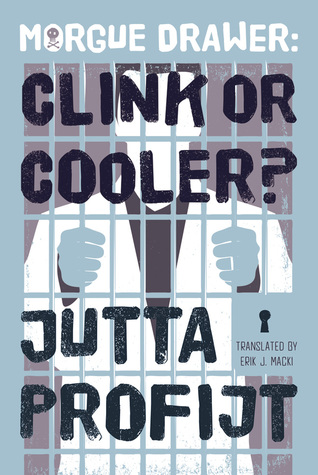

Morgue Drawer Four: Clink or Cooler? (2013) by Jutta Profijt

Pascha the unwanted ghost is still about, annoying the only human that he can contact, Dr Martin; the Goose, as Pascha calls him. Martin has taken extreme measures to control, if not rid himself, of this apparition by installing all manner of electronic gear in his home, offering feeble explanations to his long suffering girl friend about why he has an electronic net over the bed. Martin goes to endless lengths to conceal the fact that he is haunted by Pascha, though his one and only friend Gregor knows. Gregor is a man who can keep a secret.

Gregor is Herr Detective Inspector Kreidler whom Pascha rather grudgingly admires. Gregor is an action man and that appeals to Pascha, the one time car thief.

But then then two police officers appear with a warrant and arrest Gregor, who lapses into an uncharacteristic passivity. Pascha is outraged and is determined to spring him.

He needs Martin for that but Martin is completely preoccupied with his girlfriend who is pregnant. Martin spends hours supervising her, arranging her diet, instructing her in exercises, telling her when and how to sleep, to rest by sitting such-and-such a posture. Martin is a health fanatic and this he imposes on her, well, he tries to do so but Brigit has a mind of own and the appetite of more than two. She may eat as he asserts when he is there but when he is not let the chocolate cookies, fruit bars, potato chips, anything and everything roll.

The only way Pascha can mobilize Martin is by claiming to be in contact with the soon to be born child. A lie but Pascha is a much-practised liar.

For her part Brigit is bored by Martin’s Regime and she wants to help Gregor, not sit quietly inn a dark room listening to soporific music eating lettuce leaves for six more months. (By the way, this sounds pretty much Martin’s idea of heaven.)

Martin, of course, does too but not at the expense of leaving Brigit’s side. He ends up towed along in her wake.

Loved the deal Brigit makes with the sleazy night club owner. How will she explain it later to Martin?

This title is fifth in the series. What a hoot they are. Keep it up Jutta!

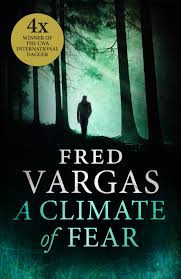

‘A Climate of Fear’ (2016) by Fred Vargas

This is the ninth title in the tales of Commissar Adamsberg, the vague, unkempt, inquisitive detective, played in a film adaptation superbly by Juan Garcia.

Juan Garcia as Adamsberg.

Juan Garcia as Adamsberg.

There are also television episodes that have all-star guests like Charlotte Rampling. In the following picture from the television production we have Adamsberg, Danglard, and Retancourt.

The characters are varied and amusing; the dialogue is human and humane; the situations stretch from the mundane to …. Iceland and back.

How does she do it, Fred Vargas, one time professor, now full time writer? Well, I hope she is at it full time because it is a big world and more of it needs Adamsberg, Danglard, and company to resolve its mysteries.

The setup in this title? An elderly woman is found dead in her bath with slashed wrists. She had terminal cancer and the gendarmes call it suicide, and following procedure they photograph the scene and present it to the station chief to sign off and close the file. Bored, he reads the file and looks at the pictures.

Odd that symbol drawn in lipstick on the side of basin.

He calls Danglard, Adamsberg’s number two, famed in the small world of plod for his vast knowledge, retentive memory, and capacity to solve puzzles. Danglard has to see it for himself in situ, and being bored, Adamsberg rides along with Danglard for an outing. The symbol baffles even Danglard and once baffled he cannot quit. Adamsberg is indifferent as they return to their desks.

Then, by chance, a woman comes to the front counter of the nick to make report, but she finds the cop shop all rather distressing and turns to leave, her mission unspoken, but Danglard passes through the lobby and he, of unfailing courtesy, addresses her with great civility. She responds to his politesse, and in short order she reports…. It ties in with the ostensible suicide.

Now Adamsberg reads the file and the plot thickens. Terminally ill or not, why would such a formidable woman lay down fully clothed, hair done, perfumed, nails polished in the tub full of water and cut her wrists? Why would a woman described as determined and self-sufficient, give way? Why is there no suicide note? Why did she struggle in her Zimmer Frame to mail a letter that afternoon?

It all does not add up to zero. There is something more to do it and it meets the eye in the symbol that even Danglard cannot decode.

As ever there are tensions among the officers, numbering about twenty, in this unit. Adamsberg’s loyal number two is Danglard, and there are others who also suspend disbelief in order to be loyal to him, too. It takes suspension because he does go off on tangents, and some do not work, but others do. The tangents come from his intuition which he seldom can explain. Adamsberg is not articulate or learned.

Against this are the positivists in the squad who want facts, finger prints, DNA samples, eye-witnesses before making a move. The metaphysical cloud shovelers who follow Adamsberg are tested in this title, and even Danglard wavers. That phrase ‘cloud shovelers’ was hung on Adamsberg and his deputy in Quebec in an earlier title, but it sticks.

Characterisations are one of Vargas’s strong points. She differentiates her characters and gives them each space, in the way Frank Capra gave character actors camera time, believing it enriches the story, rather than detracting from the protagonist. It sure does. (There days most of the diminishing breed of character actors could be, and sometimes are, replaced by CGI. [Computer Generated Images, Mortimer!])

In this tale there is a thuggish stable man with a police record, who dotes on his horses while imposing discipline on them with whistles and words of kindness that abash both Danglard and Adamsberg. There is a retired nurse who dithers, but is incisive when it counts. There is a spoiled and petulant young man of twenty who has depths none anticipated. Then there are the history re-enactors, some of whom are even odder than Adamsberg.

Most of all there are the regulars, starting with Adamsberg wearing clothes that looked slept-in and probably were, again. Danglard who will never be promoted because he is an alcoholic, a single parent with a brood that takes up a lot of time and energy, and a walking encyclopaedia as far as colleagues can tell. There are many others on the team, like the Amazon Retancourt, who are all watched over the in the office from atop the photocopier by Snowball who figured decisively in one of the earlier tales.

In this title the plot is, as always, complicated, convoluted, and obscure. Yet when it is nailed, it all hangs together. Of course, it is far fetched and some of the touches of the bizarre are, well, bizarre, and probably unnecessary but they have become the decoration on Vargas stories. The bizarre touches, the boar, the mysterious island, are well judged, if distractions.

Fred Vargas

Fred Vargas

Frédérique Audoin-Rouzeau (1957-), archaeologist by day and krimiest by night. At the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and then the Institut Pasteur she specialises in epidemiology, particularly the Black Death in Europe. Her authoritative study is ‘Les chemins de la peste’ (2003). Some dinner table conversation there I expect.

‘An Invasive Species’ (2015) by J. J. Salkeld

A new locale, a new investigator, a new approach for this jaded reader of police procedurals.

The protagonist, Owen Irvine, was once in policing and then spent a decade investigating social benefits fraud for the local council in Cumbria.

His past in policing is murky, and no doubt more of his backstory will emerge. Ho, hum. Backstories do not a front story make.

Tracing penny-ante fraudsters is not much fun for Owen but there are challenges. Mostly though his prey are single mothers trying to squeeze a few more quid from the system for their kiddies, or so they say despite the new car in front, the satellite dish on the roof, and the ashtray full of St Tropez cigarette stubs on the table.

Owen is numb, having heard all the lamebrain excuses before, each told as if unique.

Not only does the council squeeze the pounds it pays to claimants, it also squeezes those it pays to the investigators, and the chopping block has Owen’s name on it. While his record is the best, it is too good, because he has banged up more than one relative of a councillor. In this and several other ways, the plot is leaden.

Then he meets one fraudulent claimant who is different. It is another woman, but one without excuses to offer, who seems educated, and smart, and who admits her crime, and yet …. she was desperate enough to pull a stupid stroke for a few hundred quid.

Owen breaks his own rule and asks why? He has never had to ask before. Always before he is told an avalanche of reasons he does not want to hear, because he is only serving the injunction, not making the decision. This one, Clare, tells him reluctantly a story about a man who deceived her, took advantage of her, and drained her bank account.

He passes the story onto a comrade in arms at his old nick, and, by the legerdemain of crime fiction another similar case arises, and the chase is on. Well sort of.

There a reality check in this book. Time is budgeted and for a crime without violence, for a crime where there is no evidence of a crime apart from the drained bank accounts, the time allocated is half a day. Imagine what a Star Trek film would be like if there were a Star Fleet budget. No more warp engines, Captain, we are out of dilithium crystals and do not have the gold-pressed latinum to pay for more until the end of the space-year.

Ah but the recently sacked Owen, who is more or less financially independent (because he owns his home, has a vegetable patch, a trout stream, an eternal Land Rover, and few needs), has plenty of experience in finding people who do not want to be found and time on his hands.

That is the set up. A pretty good one, if only it had been told with some élan or wit.

This reader felt the boxes being ticked. Perhaps that is inevitable in the first title of the series. Owen’s backstory is forced into the foreground. To do so makes it very wordy and slow. Though Owen is supposed to be laconic and reserved, but he talks about himself incessantly to get that backstory out. To enhance Owen he is made a victim in the dismissal by the council and by implication in his earlier dismissal from the plod. A poor put-upon hero, yet again, martyr to his virtue. All of this background interferes with any interest in the foreground. The time and place are described but they take a distant second place, and that is a shame, because the regional setting is what I found attractive at the outset.

Among the compensations are some lively scenes. The puzzling interview with Clare is one. Another is with a fraudster who seems to have done it just for fun and enjoys discussing it with Owen. Then there is the police officer who is uninterested in the information Owen passes on. They have a pissing contest, as they say on Channel 7Mate. Predictable but well done.

Regrettably, but perhaps inevitably in this kind of context, all the characters sound alike, use the same speech mannerisms, idioms, and vocabulary. All the police officers sound alike, even the educated Asian woman. Indeed, Clare is only distinctive voice in the early going, and that is a plot device, to be sure, and a good one, but it emphasises how monotonic the rest are, including Owen.

J. J. Salkeld, a very industrious writer to judge from the array of titles on Amazon. Strength to his arm.

J. J. Salkeld, a very industrious writer to judge from the array of titles on Amazon. Strength to his arm.

It is the first in a lengthy series and perhaps things come together. Time will tell, if I get back to it. I found it easy to put aside.

‘Schrödinger’s Gat’ (2013) by Robert Kroese

A noir krimi with quantum physics!

I selected it for the Kindle because I smiled at the title on the cover. Wait! There is more. It is a krimi based on quantum physics. Yep! (It also represented light relief from reading Nietzsche.)

Huh?

That is how our protagonist reacts. ‘Huh?’ He is Paul, one very depressed loser in San Francisco whose path crosses that of Tali, who saves his life but she runs away when he tries to thank her.

A chartered loser, he is used to people avoiding him, but not quite like this. He pursues her, and, without breaking stride, she promises to explain all, but first he has to grasp some quantum physics.

Huh? Well, all right.

But before she can explain much, she first has to do a few things, and, well, seeing is believing, and Paul sees enough to … believe, a little. She arranges to met him for a further explanation but she is a no-show.

Huh? (Paul has a small vocabulary.)

What is a fellow to do but Google it; he reads up on quantum physics, advising readers in direct address to skip that part of the book. I should have, but I didn’t. Had I, that would have been in total about three-quarters of the book. Of course the cat comes up.

During this ersatz research he comes across the name of a Stanford scientist, the summaries of whose work on websites sound like Tali’s interrupted exposition. While the scientist seemed to have had a fine career strewn with publications and accolades until a few years ago when he, too, seems to have disappeared. Huh. (See!)

But even a loser can use the telephone book and Paul finds a street address that might be that of the professor. Hey, presto!

Well, that’s a lead. What would Philip Marlow do? Doh! He would go see the professor.

It is a mile-a-minute, except for the asides on matters quantum physics, and is it droll. dry as dust. Regrettably the asides on QP increase, and go on and on. The mile-a-minute stretch like a Salvador Dali watch.

Oh, and the cat. Did I mention the cat? Well, there is neither a cat nor a gat. Which word I always assumed was derived from Gattling gun, the rapid fire weapon developed in the Nineteenth Century, precursor to the machine gun. Another weapon so deadly that its inventor thought it would end war.

The set-up sounds better than it reads. It takes a quarter of the book to get the characters lined up around all the lectures on QP. There is so much preliminary fussing that it reminded of those dreadful Sunday lunches where the fussing over nothing is continuous so that the food does not appear until 4 pm by which everyone has had too much alcohol and a headache either from the drink or lack of food.

Then Paul inadvertently, if you can believe it, drops a homemade bomb into the fountain at a shopping mall and it kills a great many people. The cops arrest him and in his cell he reads Kant on metaphysics and shares it with the reader. Which is harder to swallow the bomb at the mall or Kant in the clangour? What is worse is reading it.

By this stage three-quarters of book has elapsed without any further sighting of Tali, and no explanation of events that this reader can follow. Where is that damn gat? Where is Schrödinger? Or even the cat?

Eventually this mass murderer is sprung on bail. What! Fire that DA and get one keeps capital criminals in the slammer.

There is a final confrontation of sorts but mostly it is like one of those post-modern conference presentations where the words flow but the meaning does not. The characters talk each other to death, or something. Hard to tell through my glazed eyes. Since this is San Francisco there is an ever handy earthquake to settle matters.

There is a long afterword with more QP. Enough, already!

Robert Kroese, who has many other titles on Amazon.

Robert Kroese, who has many other titles on Amazon.

Following the afterword is a biography in which we read that the author wrote his first novel in second grade. Is this it?

I did make it to the end, but only with quick thumb work flipping the pages with very little reading and less pleasure.

‘A Small Death in Lisbon’ (2002) by Robert Wilson

I break my rule and write about a book I disliked, doing so in part to crystallise what it is that I did not like about, and why I tried so hard to read it.

I tried to read this book years ago, and was recently moved to try again since my interest in Portugal was kindled again a few months ago by reading about the Carnation Revolution of 1974 but my efforts to find Portuguese novels that I might like have failed.

Yes, I have read some by that Nobel Prize winner, José Saramago, but found them desiccated, didactic, and dull. In short, lifeless. They told me nothing about Portugal or any Portuguese.

Reviews of lists of Portuguese novels on websites did not help either where even the krimis were described by the deadly term ‘surreal’ that is code for incomprehensible and self-indulgent which some mistake for creativity. On such lists I found ‘Ballad of Dog’s Beach’ by José Cardoso Pires which I read and reviewed elsewhere on this blog. It did not inspire me to choose another title from such lists. As an indicator of nonsense the term ‘surreal’ is as reliable as the label ‘post-modern.’

Robert Wilson is routinely accorded the accolade of a best selling author on the covers of his many novels from major publishers. All hail. The reviews in credible sources are respectful, if not enthusiastic. Knowing that I know nothing, I tried again.

It has a split story line, then and now with some in-between, and the reader, I guess, is supposed to be puzzled about how they come together. Me, I just assumed some hocus-pocus would bring them together. I cannot abide this approach to story-telling because it puts responsibility on the reader to make sense of what is written. This joke is not for this folk.

The respectful reviewers say it offers a travelogue of Lisbon and that is what enticed me to read the book both times. So on I went, screen-by-screen on the Kindle. My dentist does not approve, all that gnashing, grittimg, and grinding of my teeth which will undo his good work. With the iron discipline for which I am famed, I quit — again — at 61%, according to the Kindle.

Here is what I found as I made my way to that 61%.

We have Klaus Felsen a German businessman forced to go to Portugal in 1941 to buy rare industrial metals for the Nazi regime and to try to prevent the British from getting them, too. It seems he is the only man for the job since he speaks Portuguese, learned from a few weeks with a Brazilian woman. Ah huh. Fluent no doubt. It is February 1941, and there is one reference to the Eastern Front, though there was not one until 22 June 1941. The hindsight is all to evident throughout.

Sometime in the 1990s we have world weary inspector Zé Coelho, who mouths gratuitous criticisms of the society he serves, and despises those who cooperated with the late and unlamented Salazar regime, a group that would have included most of the country. He wears his alienation on his sleeve. Everyone he meets is awful. Especially those with money. So it goes. When figures in police procedurals engage in this kind of cheap cynicism, my supposition is that the reader is to take it as social criticism. Ever the rebel, I take is as cheap cynicism.

There is a lot of coming and going in Lisbon of the 1990s, and I liked that. I used a Google map to follow some of it on the iPad. That kept me going as long as I did.

The book also features much sex. Both of the protagonists, Felsen and Coelho, are irresistible to every woman they pass. There is enough detail to satisfy a gynaecologist.

Felsen, the good German, also goes in for murder and torture, and these deeds are also lovingly described from anatomy textbooks: wires to the genitals of the helpless victim. No electricity, just wires. The thugs, these he kills with rocks.

Time passes in the back story from 1941 and Felsen remained in Portugal when the war ended. He gets even with all his enemies, in part, because of the love of Eva. Who? [Sound of violins over the screams of his victims,]

The Portuguese peasants Felsen enslaves to his smuggling operation are described in bestial terms that must give some armchair readers a frisson. Me, I thought how simple-minded such characterisation is. For a dose of reality read the nature poems of John Clare (1793–1864) a day-labouring peasant just like those in this story. If people do not live in cities and read books, they cannot be as fully human as … the author, the reader, the editor. Thugs live and work on Bond Street, too, and even in some universities, I am told.

The preoccupations with sex and money can be readily interpreted in two ways. The first is ‘give them what they want.’ If it sells, write it. Here we may see the hand of the publisher pushing the author along. The other is the projection of the author’s own fantasies onto his characters. Pick one.

There are no compensations in the prose. Much of it is workmanlike and gets us from A to A1. However, there is far too much that is overwritten. ‘Overwritten?’ one might ask. ‘What does that mean?’ Here are a few examples;

‘her knees looked tired’

‘an in articulate shriek’ from a closing door

‘an enclosed man’ who was waiting in the alley

his ‘breath was cigar streaked’

she rose on ‘strong legs’

the ‘walls drank in the evening light’

the school girls began an ‘elephantine dancing’

There are many, many more examples of this overwrought and meaningless prose. I just stopped highlighting them on the Kindle. Each time, this slow wit, had to read the sentence twice in the forlorn hope that there was a point to the prolix prose. Nope.

When I gave up I did take a look at the comments on GoodReads and was once again confirmed in the conclusion that it is pointless using that as a reference. The narcissism (look it up. Mortimer) of many comments allows me quickly to skip most entries, and the others read like support of relatives.

Nota Bene. We watched two episodes of the ‘Falcone’ krimi television series derived from another series by this same Robert Wilson set in Seville and found them gratuitously anatomical in the violence for no other reason than to get a restricted rating to make naive viewers think they were getting something hot. While we liked the travelogue of Seville, it was not enough to put up with the plucked eyeballs and roasted human flesh. The effort to shock is so adolescent.

I hesitated a long term before publishing this, but decided to get it out the door. Reading the imbecilic reviews on GoodReads stimulated me to add my two cents.

****

What I would like would be a krimi set in 1974 as the Carnation Revolution unfolded and in the heady-ing and confusing days that followed, catapulting Field Marshall Antonio de Spinola to the head of a committee of national salvation and driving the eternal Salazar regime into exile.

Perhaps such a book exists but I have not yet located it. The dictatorship in the person of President Marcello Caetano refused to abdicate to the upstart captains who led the uprising, and insisted on entrusting the government to a high ranking officer who, of course, had also to be acceptable to the upstarts. There was only one candidate, Spinola, whose public and private criticisms of the regime were known even if uttered sotto voce and published abroad. He did not want the job, the captains did not choose him, and Caetano did not want to concede, but the hour called the man.

Enter Spinola, pulled from one side and pushed from another. The captains wanted a quick result before their tissue thin conspiracy unravelled so they accepted Spinola as the only senior figure they could tolerate. He took on the thankless task as a last service to the country. No biography of him is available in English, or I would turn to that.

If a prospective writer wants the job, here are a few tips.

Make it linear. Have a protagonist who is not the centre of attention but a prism of others.

Also please emphasise Lisbon as a character in the story, not just a backdrop, its hills, it redolent history, the balcony flowers, the worn steps, its narrow streets, the ubiquitous churches, the funicular, the prayer apses on the twisted streets, the allure of the Azores, the stifling shroud of an ancient Catholicism, and the repression that hung over everything, the secret police, mysterious disappearances, political prisoners, the nearby Spanish border and the sclerosis-ridden dictator still crouched behind it, and the exiles in Brazil broadcasting back to Portugal.

Remember also that there were Portuguese military officers, serving and retired, in 1974 who had been volunteers in the Spanish Blue Division with the Nazis at Leningrad, including Spinola himself. Most of all, remember the three colonial wars Portugal was engaged in at the time in which Spinola alone had secured victories and made peace. Add the pirate attack by Portuguese exiles on the cruise liner the Santa Maria a few years earlier. In the larger environment there is the Cold War and the developing European Union. Rich pickings.

In the foreground perhaps the tension might spring from bringing together an odd couple, say an enemy of the regime with a defender, and each discovers something of value in the other. The stiff devout old guard police investigator who had done military service in Africa teamed with a youthful critic, maybe a journalist. The journalist discovers the police officer is serious and just what he seems to be, simple and honest, not a perverted pederast hypocrite. The officer discovers the journalist is a patriot who wants to elevate Portugal not a slavering communist set on destroying the country and raping nuns.

There are plenty of incidents to choose from, even before the radio music signalling the rebellion, and then later the military counter-coup, the subsequent communist effort to seize power as Lenin did in October 1917, the democratic descent into confusion. All this was in the cities, while in the countryside life continued to follow the rhythm of nature. Or did it? Maybe not on the Spanish border. Maybe not on secluded coastlines where small boats might land unobserved, perhaps from Brazil.

Add to this the reaction of Big Brother in Spain. Franco was still a factor, catatonic though he was.

I have watched some of ‘Capitães de Abril’ (2000) on You Tube without the benefit of English subtitles. Earnest, this I could see, but lacking in tension to this distant viewer.