Another intricate krimi from this master, Ross Macdonald, he of California sunshine noir.

This is Macdonald’s take on the generation gap of the 1960s. Young Davy and even younger Sandy seem bound for mutually assured self-destruction while taking a few others with them.

Sebastian, Sandy’s father calls in Lew Archer to find them and return Sandy home. While Sebastian offers a good front, it does not take Archer long to realise there is no back to this front. Sebastian failed to make the transition from a promising young businessman to a successful one. Behind the trophy wife, model home, and new car Archer finds a loveless marriage, a silent house, and many unpaid bills, while Sebastian dances attendance on his wealthy boss, Stephen Hackett, in the hope of….something.

Then Hackett is kidnapped at gunpoint by none other than the two teenagers, Davy and Sandy. Unbelievable but true. Why?

It is a tangled skein and by the end I needed a genealogical chart because this one spans three generations. It is a cocktail of Macdonald’s themes, an unloved child, a misused child, illicit drugs, denied kinship, a surly subordinate, a very nice woman who knows too much, a venal older woman with a toy boy husband, and assorted police officers including a bent one.

The body count reaches Midsomer proportions while Archer develops, applies, tests, and rejects alternative hypotheses until at last one fits.

While the principle cast seems to consist of disparate people with nothing in common, in fact, on that family tree, they are entwined by marriage and murder, the latter seeming to be the stronger bond.

In addition to the rebels with a cause in the teenagers, Macdonald also adds some Cain and Abel. And as frequently the case in his novels, there is a black widow who has consumed two husbands.

Against the array of vipers and the lost teenagers, Archer meets some very solid citizens. Alma in the nursing home, a school guidance counsellor who goes beyond the call of duty, a security guard who keeps his word come what may, many others who lend a land, like truck driver who finds Archer on the highway, Al at the sandwich bar, and gas pump jockey with a calliper on his leg, each of whom reminds the reader of all the decent people out there.

The imagery at times transcends the story as when Archer admits to himself that he likes the work, late at night, driving from one place to another like an antigen connecting cells in the great body of Southern California.

Category: Krimi

‘Murder on the Trans-Siberian Express’ (2001 ) by Stuart Kaminsky.

This title reads like short stories woven together, one of which concerns the Trans-Siberian Express. Only half-way through the book does our protagonist get on the train. The details of the train and Siberia read like excerpts from Wikipedia.

Though it is presented as a police procedural with the three teams of detectives working separate cases, pace Ed McBain’s 87th precinct, the ominous villain on the train and the plot that leads to the train is more of the thriller. Credulity replaces credibility.

The three stories are told back to front in alternative chunks of prose, which this reader finds confusing and distracting.

Though Porfiry Petrovich Rostnikov is the central, continuing character in this series, endowed with an artificial leg to give him some distinction, I found him to be hallow. Tap, tap there is nothing inside. He is very polite, very patient, very clever…. he has a family…. our hero is motivated by justice but the boss is ambitious for political power and is more interested in accumulating files on those he can manipulate than banging up crims. So far, so carbon copy.

The three cases.

1. The subway stabber who is a nutter of no interest. This one is a procedural. Much plod and a trap that almost backfires.

2. The mysterious object on the train which turns out to be very little as far as I could tell. The thriller.

3. The kidnapping of the heavy metal musician whose kidnapping was arranged by his father to teach the prick a lesson. I identified with the father on this one.

The Trans-Siberian railroad in October 2016 when we crossed it.

The Trans-Siberian railroad in October 2016 when we crossed it.

This is one of dozens of titles by this author, and to this reader it has the same narrative structure of the one other one of his I tried to read. All done by the numbers. Yet the cover proclaims it to be a best seller and it was published by a reputable firm. Go figure.

Stuart Kaminsky

Stuart Kaminsky

There are some soppy comments on the blanket of white snow in Moscow. Anyone who have lived in a big city will realise snow is usually grey like the sky until it turns brown from the pollution and churned up by cars and pedistrians into brown sludge. There is nothing nice about it after thirty-six hours.

‘The Second Death of Goodluck Tinubu’ (2010) by Michael Stanley.

An exotic setting for this krimi in the heart of Africa. It opens in a tourist camp at the Okavango Delta, at the confluence of the Chobe and Linyanti Rivers where Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Botswana meet with Angola not far away.

The red dots are tourist camps on higher and drier ground.

The red dots are tourist camps on higher and drier ground.

The nearest town, for those consulting a map, is Kasane near Victoria Falls. The waters are replete with crocodiles, water snakes, and hippopotami.

‘Don’t fed the crocs. Keep your hands and feet in the boat!’

‘Don’t fed the crocs. Keep your hands and feet in the boat!’

There are many descriptions of sunsets and sunrises in workman-like prose. Our hero is Detective David Bengu, known as Kubu because of his resemblance of his manly figure to a hippopotamus.

It is a small tourist camp; one that is decidedly downmarket: Basic, no luxuries to attract high-paying guests. It represents the inheritance of the owner, and it is run by Dupie who has spent his life in the bush. The area is a swamp more than anything else and boats are essential and even more essential is someone who knows how to handle them in the rivers, the current with those crocodiles and hippos have to be avoided.

The dozen or so guests are a combination of Europeans and Africans, white and black, local and foreign. That is the norm in these camps, we are given to understand.

The abnormal is that one of the guests, an African black name Goodluck Tinubu, according to his driver’s license, is found dead in his tent one morning. He was very clearly murdered, his throat cut. The local plod from Kasane arrives and deploys the usual conventions of the police procedural.

No sooner do the police investigate the camp staff and the remaining guests than another of them is found dead, with his head smashed by our old friend, blunt instrument. Two murderers in quick succession within a few meters of each other is too much for the local plod and a call goes to distant Gaborone for help. The Number One Detective Agency is not available so our protagonist takes the case.

It gets worse when fingerprint identification shows that the the titular first victim died thirty years earlier during the Rhodesian War! This is his second death.

The conventions then go into overdrive. We learn Kubu’s backstory, his likes and dislikes, his capacity for beer, his vexed relationship with his boss, his family life… His constant preoccupation with food and drink to the exclusion of much else. In a word, boring. The only part of this backstory that I found amusing was the report of the schoolboy experiences with the game of cricket, and even that was a distracting digression.

Much more interesting are the legalities, political niceties, and social morēs of that part of the world. Though it is far away, South Africa looms large. While the Rhodesians War ended thirty years before, its baleful influence remains palpable. Many of the people we meet in the story were displaced first by the war or then later by the malignant regime that now rules, one set of chains having replaced another. Underlying all that recent history, the ancient tribal differences remain the bedrock of relations among the locals.

The camp is not owned but rather is a concession, one about to expire. The owner of the concession is not at sure she wants to retain it, and even if she did, she is not sure she has the means to do so.

Each of the guests is limned, revealing that each has a story related to this part of the world. The wars for independence and civil wars there left scars, physical and psychic on both the participants and their progeny. And no krimi is complete today without a reference to the drug trade with vast amounts of money that entrails.

The detail of the camp, the tourist trade, the relationship among the actors are all very well done. There is also some insights into the plight of Zimbabwe that remain with the reader. I would prefer much more of that and much less of Kubu’s diet.

The authors are a pair, who seem to work together seamlessly. Well done!

Michael Sears and Stanley Trollop

Michael Sears and Stanley Trollop

This is the second title in the series. In the way that publishers have of confusing the international market, this book has another title in the United States, ‘A Deadly Trade.’ A reference, no doubt, to alert readers to the drug trade. Strikes the sledge hammer of subtlety again.

I see there is a third and I will get to it one day. I find the exotic setting very interesting but Kubu himself is a bore. He is always far more interested in himself than anything else.

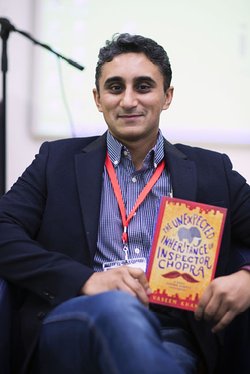

‘The Unexpected Inheritance of Inspector Chopra’ (2015) by Vaseem Khan

A charming krimi from Mumbai in India, full of colour and movement like the city itself. Inspector Ashwin Chopra has been forced to retire at fifty because of a heart attack. The upright Chopra has long tried single-handedly to rid India of crime and corruption. He is a man with a mission who has been side-lined! But for how long?

Coincidentally, Copra’s much loved uncle, a father figure, leaves him….a very young elephant! Huh? Chopra lives in a gated community on the fifteenth floor of a modern condominium. While there is plenty of storage in the basement, there is no room for an elephant, large or small, young or old. Still Copra must accept the elephant, Ganesha, named for the god, out of respect for his departed uncle.

Poppy, Chopra’s wife, is taken aback, nonplused, and…., but before she can lay down the law, the egregious Mrs Supramanium, a neighbour, barges in and demands removal of ‘that creature!’

That’s it! Under no circumstances will Poppy concur or agree with ‘that woman!’ The elephant stays! He is tethered in the courtyard, minded by the doorman as a temporary measure.

However, the elephant is depressed, head down, wobbly on his feet, saggy tail, trunk deflated, and — worst of all — will not eat. Chopra does not know what do, so he buys books and consults a zoo keeper and later a one-time circus trainer. Strangely, he does not turn to Dr Google.

Of course, the book-writing scholars disagree with each other since that is how careers are made, leaving him little wiser. These books by scientists are desiccated and abrupt without any practical information for the urban elephant owner. But he also finds a memoir by an Anglo-Indian woman who reared an elephant, more or less as a pet, and it does inform him on some practical points. That is a start. More importantly, it heartens him to make the effort.

Then there is the uncle’s letter entrusting the elephant to Chopra, which in part said ‘This is no ordinary elephant.’ Uncle was not one for exaggeration or superfluous remarks. Thus Chopra proceeds with care.

Into the mix comes a crime that Chopra, retired or not, cannot ignore. An innocent young boy has been murdered and no one cares, least of all the police at his old nick now with a new supervisor. In addition, a one-time nemesis reappears. The thread unwinds with some of the usual twist and turns, but then there is the elephant in the room. Literally in one instance.

While walking Ganesha to a veterinarian for yet another consultation, Chopra sees a lowlife who used to consort with the nemesis and the old impulses take over; off he goes on the trail with Ganesha in tow! Into the colossal glass-and-steel Mall of India he goes, brushing past security guards who suppose no elephants are allowed. Too little, too late are their efforts to impede entry. Then there is the escalator ride! What a tribute to German engineering. What a show for the shoppers!

A Cadbury chocolate bar gives Ganesha a powerful incentive to lumber along. When obstructed, Chopra declares Ganesha a police elephant. Police dog. Police elephant. Out of the way!

Ganesha lives up to the appellation more than once. In turn when the monsoon hits, Chopra rescues the tethered Ganesha from a torrent. They have bonded.

Along the way there is much elephant lore. Meanwhile, Poppy thwarts Mrs Supramanium, while coping with her crotchety mother who is not keen on either the elephant or the husband.

Vaseem Khan

Vaseem Khan

Quite a trip and also a fine arrival, leading to the next title in the series. Loved it.

At least some researchers into African elephants, much larger than Indian ones, have declared them free of Machiavellianism. All will be explained upon request.

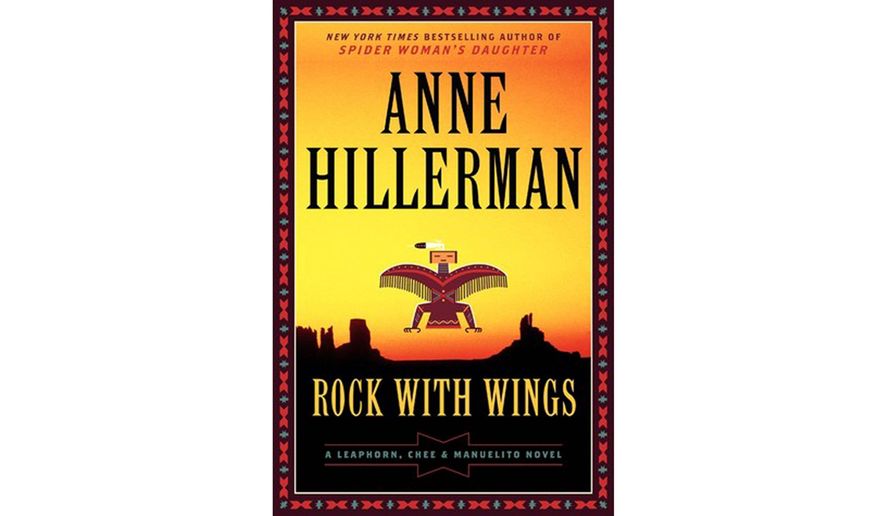

‘Rock with Wings’ (2016) by Anne Hillerman

Now that Bernie has moved to centre stage, this long running series has changed somewhat. In this outing, her husband Jim Chee goes to Monument Valley, while she minds the store in New Mexico. Whoopee! Monument Valley! A place like no other.

That made it must-reading for me, and indeed Hillerman does well in conjuring up that marvellous, unique, in this telling — mysterious, and, when the sun goes down, frightening place. The indian cosmology of those rocks added depth and complexity to the other-worldly visuals. The monuments were left behind by the creator gods to show the Navajo that they are not alone in the cosmos.

Ford Point in the foreground where the horse is. I have stood right there and looked for the stagecoach with John Wayne in it.

Ford Point in the foreground where the horse is. I have stood right there and looked for the stagecoach with John Wayne in it.

Jim meets several tourists and they are well drawn, the lost and exhausted Germans, the thrilled Norwegians, the awe stuck New Englanders. As always in Monument Valley, there is a film crew, whose producer has no interest in film and that explains a lot about movies these days. Although the resolution seemed too complicated.

I wondered in vain why the automatic assumption was that the grave was not real. No one moved one handful of sand to find out what lay beneath, if anything.

All the bases are touched from Elephant Feet, the Mittens, Standing Rock, Balance, Gould’s Trading Post, ‘Stage Coach,’ Ford Point… and each time I shouted out I’ve been there!

Ship Rock in New Mexico near where Bernie and Joe live and work.

Ship Rock in New Mexico near where Bernie and Joe live and work.

The mad Greenie was a nice touch. Anything to install those solar panels!

The explanation of the dirt boxes was weak after all the build-up. Though I liked the change of heart of the driver.

Anne Hillerman

Anne Hillerman

Bernie spends far too much time worrying, worrying about her frail and elderly mother, her wayward sister, and then meta-worrying about whether she is worrying too much or too little. Worry. Worry. Worry. Boring! There are pages and pages of it. She then turns to worrying about the absent Jim. Much worrying followed by meta-worrying. Is this Chick Lit? I don’t know, sheltered as I am from the genre. Does that makes this a cross over, Krimi-Chick Lit or Chick-Krimi Lit? Or is it Worry-lit?

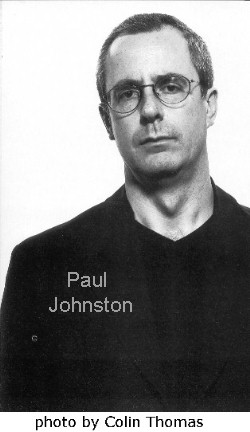

‘The Water of Death’ (2011) by Paul Johnston

Paul Johnston devised and wrote a krimi series set in a near-future Edinburgh, after the United Kingdom disintegrated into warring city-states following a singular concatenation of disasters, fiscal, climatic, and social. They ran out of money, the drugs and their lords took over, and climate change came with a vengeance. Ripped from today’s headlines, the cliché-writing publicist would say.

Not quite, because Johnston added a delightful twist. The independent, impoverished people of Edinburgh turned to the ages for salvation. Huh?

They established a Platonic society, ruled by philosopher-monarchs whose directives are executed by guardians, who in turn are aided by auxiliaries. There on the rock, in Edinburgh Castle, the philosophers meet and decree.

In the first generation they were idealists suckled on the book, ‘The Republic,’ but as new members joined and founders died, pragmatism became the order of the day. The reality combines Platonic forms with KGB surveillance.

The books are, however, not expositions of Plato, nor critiques, but rather krimis. The exposition comes out as parts of it are relevant to the narrative at hand.

The protagonist is Quintiliian Dalrymple, a demoted auxiliary, who is called in when needed as an investigator since he combines the training of an auxiliary with the freedom of a citizen, i.e., he does not wear a uniform that frightens other citizens. He has been needed eight times. I have read them all, and this is the last in my reading though not chronologically last. I missed it earlier. Demoted? Read on.

Edinburgh ekes out a living by selling gambling, drugs, alcohol, and prostitution to wealthy visiting Arabs and Asians. They seem to love those red heads. These treats are denied the locals but dished up to the the foreigners who come and pay.

Of course, no Scot can be denied whiskey so they have their version, but not the good stuff reserved for those who pay with hard currency rather than with worthless philosophical scrip. Yes, of course, there is black market. Among the Edinburghers sex is done on a rota as though physical exercise. The men and women live in barracks’s and have barracks names and numbers, not names. There is neither privacy nor intimacy. All of this is to reduce egotism, the intrusion of private family, and so on…..

Then some fiend puts poison in a tourist whisky bottle, which is stolen and drunk by a citizen, or so it seems. That is bad enough for morale, but if a tourist dies, Edinburgh will, too. When all else fails, Quint is called in to prevent such a catastrophe.

The unique set-up is spoiled by Quint’s constant churlishness, I am afraid. He has to make a smart-ass comment every time, on everything, and to everyone. Where does he get the energy from on the 2000 calories-a-day diet? His auditors in turn have to frown and scold him each time. He is adolescent in his desire to shock and offend as though he were a schoolboy. If this by-play, let us call it that, were cut from this title, it would reduce the book a lot. Really, Quint. Grow up! Quint also spends a lot of the reader’s time worrying about his sex life. That can be diverting in some writers but here it is a mantra repeated for its own sake, again, and again, to pad out the pages.

There is no compensation in the plot, which veers from one pillar to another post without much rhyme or reason, except insofar as it allows Quint to fire off more from his endless supply of bon(ring) mots.

The labor in maintaining a series must be very difficult and it shows in this book, where everything is laboured, laboured again, and then laboured once more anew. That it is a hot summer is said a hundred times. if it is said once. Got it.

The larger point is that Enlightenment (that is how the regime characterises itself) Edinburgh is as destitute as say Seoul in 1949. Point taken, but I doubt that anyone living in those dire circumstances spends as much time as Quint does whining about it. It takes all their time and energy to struggle on in such poverty. Somehow Quint has the luxury to take the time and energy constantly to complain, carp, and criticise. That it the writer’s conceit.

I see that there is another one out this year. Maybe, maybe not.

The Galton Case (1959) by Ross McDonald

This krimi could serve as an object lesson in a workshop on plotting a crime novel. Every word, every gesture, every line of dialogue, every character plays into the plot in the end.

I grew restive at some of the to-ing and fro-ing and dialogue, only to realise later that it all added up. It is such jewell that Jacques Barzun can only say of it ‘One of the best Lew Archer stories.’ Yes it is and that is saying a lot.

It combines the ingredients to be found in most of his krimis. A wayward child of privilege, an emotional void, a lonely woman who clutches at a phantom, an unbalanced beauty, a too-good to be true husband, an impulsive doctor, along with some lowlifes from Lost Wages and some small town cops trying to do right with meagre resources.

Is the beautiful wife really unbalanced? Does the other lonely woman sense something beyond the paperwork? Is the husband long-suffering or something else? Read the book to find out.

There are also some scenes in Mcdonald’s native Canada, in Ontario, as Archer digs deep into the past of the missing man and the found boy. (It makes sense in the story.)

The problem with reading about Archer is that it sets an impossible standard for any other writers. Not only are the plots perfect, but the prose is crystalline.

Albeit there were some false notes, as when Archer plays the smart-aleck with the local plod on first-meeting. It is out of character for the Lew Archer I have known all these years, and it seems contrived. Was McDonald experimenting?

Pretty Boy Paul Newman played Archer in two films, but as per Hollywood logic the name was changed to Lew Harper to follow Newman’s ‘H’ movies, Hud and Hombre. Thus ensuring few Mcdonald readers saw it. First invest money in buying the property and then dilute it. No doubt the executive who did that gave himself a big bonus. Genius.

The Newman films were about ten years apart: ‘The Moving Target’ and ‘The Drowning Pool.’ Each is fine with some superb performances from the whole cast.

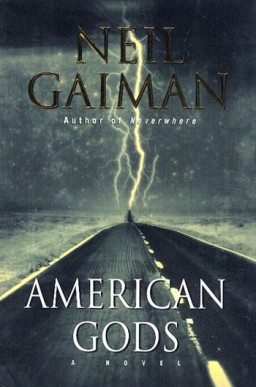

American Gods (2001) by Neil Gaiman

An innovative novel that has mystery in it. An oddball nicknamed Shadow is released from prison and bumps into a strange man who offers him a job as a gofer; with no other prospects Shadow agrees, and slowly finds the man even odder than he first thought.

The genre is mixed, combing fantasy, krimi, satire, mystery, and horror, to paraphrase one of the many laudatory reviews. Others describe it as masterpiece of innovative fiction. Ho hum. It seems to have been written for jaded reviewers and awards panel members, not for readers in search of diversion, enlightenment, engagement, and pleasure. It is indeed very well written and the author is a story teller at heart. that much is clear.

To this reader it suffers from the complaint of much self-consciously modern, genre-bending literature in that it tries too hard to be different. We have multiple perspectives, most of which are unreliable, combined with non sequitur narrative lines that fizzle out, intercut with stories from times past with no discernible connection to the foreground story of Shadow.

Spoiler alert. The thesis is that the gods are among us, and that is cleverly done. There is rough division between the old gods and the new gods. The old ones are two kinds: native, e.g., Indian, and immigrant. The waves of immigrants to North America in the 18th, 19th, and 20th Centuries brought their gods with them in their minds and hearts – which vivify the gods. But life and times changed for the Indians and for immigrants and the Old Gods have worn down, no longer worshipped, no longer the object of sacrifice, no longer venerated, or embodied in effigies as tokens, no longer…. Without worship and offerings, the powers of the Old Gods diminish. Now these gods are reduced to driving taxi cabs (for generations) in one case), repairing refrigerators, living in self-imposed exile isolated in the north woods for near eternity. Yet most of them still hold on and out. Though some want to make the best of their reduced circumstances and have no wish to reclaim their former powers, others cannot endure a forever of cab driving or repairing refrigerators and propose a war with the new gods. Clever that.

Rising are the new gods, and this is the satire. They are media, represented by the Barbie Doll who reads the weather on every local television channel in the world. This one struck a chord of recognition in me. Another new god to be placated is television and the scenes involving ‘I Love Lucy’ gave me a cackle. If only!

The New Gods are moving decisively to eradicate the Old Gods, who have squabbled among themselves for centuries, and now find it hard to put aside these old enmities to pull together in defence. Shadow is drawn into this no (hu)man’s land between these two forces, and his gradual realisation of it, reaction to it, and acceptance of it, are very well handled. All in all, this clash of the gods makes as much sense as reality does, and this is before Trump Donald became president.

The end of the final negotiations between the old gods and the upstart new gods occur in a place I know well: the geographic centre of the continental forty-eight states. And where is that class?

Lebanon, Kansas.

It is very well described in these pages on a wintery night, long after the tourist season has finished, in a dilapidated motel nearby with swirling wind coming off the Great Plans carrying the scent of petrichor combined with the portent of much worse to come. It is brooding, and though vast, somehow confined. The author really makes it seem more like a gothic haunted house rather than the wide open and flat space of northern Kansas.

Reader, ‘petrichor?’ Look it up (in a big dictionary).

I know Lebanon KS from several visits and because it loomed large in my adolescent cosmology because it is only a few miles dues south of Hastings near the Platte.

The Old Gods are Norse, and mythological like an embodiment of Easter (but not Santa Claus).

The mix is too rich. Many story lines are started and few are finished. I grew weary of thumbing pages on the Kindle when the digressions set it. No doubt my loss but I like following a path, not stumbling through the underbrush in a zig-zags. This sort of reading reminds of defences against U-Boats, treating the reader as an adversary to be fooled, tricked, and deluded: Modernism is thy name.

In my reading, albeit incomplete and superficial, there is no divinity from the great religions, like Jesus, Allah, Buddha, or such. And no reference to Shinto.

There are however long sections on coin tricks, which Shadow learnt in prison to pass the time. Perhaps the emphasis on this skill is explained somewhere later but my Kindle flipping speed passed it by.

Neil Gaiman

Neil Gaiman

Talking to a friend a few weeks ago, he said he had read and liked it. It seemed an odd choice for him and later when thinking about starting another book, I turned on the Kindle and decided to try it as a change of pace. Not to my taste.

‘Vita Brevis’ (2016) by Ruth Downie

The further adventures of Ruso, medical officer late of the 20th Legion, and his British wife Tilla, and their adopted daughter Mara.

A turn of fortune brought them to the capital of the world, Rome. Tilla resisted leaving Britannia, but needs must and off they went.

She found Rome even more awful than she expected and her expectations were very bad. For his part, once there, Ruso cannot quite remember why it seemed a good idea to go to Rome. Tilla heroically resists saying ‘I told you so’ for as long as she can. Not long that.

The disorder, noise, smells, expense, rudeness, violence, are just some of the vita Romana. Little has changed since then, to be sure.

The patron who sponsored their migration, luring Ruso away from his army sinecure, where he had long since worn out his welcome, is likewise not sure now that it was a good idea. There seems to be nothing for Ruso to do, and Rome is full of doctors, snake-oil salesmen and, for that matter, saleswomen, faith healers.

However when Doctor Kleitos is called away to the country, Ruso is nominated by his patron as the locum. Excellent, thinks Ruso, because the quarters will get them out of the overpriced hovel they are renting and the surgery will generate some sesterices.

Odd though that Kleitos seems to have taken everything not bolted down, tables, chairs, crockery, and all his medical records for a temporary leave. Even odder that a dead body is delivered to the front door in barrel.

Thus does the plot thicken.

Ruso is so wonderfully vague and easily distracted, so painfully well meaning and imperceptive, technically adept at medicine and foolishly brave that he charms the reader. TIlla is so determined, impetuous, and resourceful it makes the reader wonder how the Romans ever conquered her tribe.

She sings Mara to sleep with British songs of triumph, while Ruso worries about the dosh he does not have, and puzzles over the fool’s errands his patron dishes up. What is going on? Then there is that dead body….. It has nothing to do with them but it has put a curse on the medical practice, compromised the patron, and generally gummed up the works. Like it or not, they are going to have to figure it out.

Apart from the historical setting the most amusing elements in these novels is the by-play between Ruso and Tilla, man and wife. At one point, amid the confusion, she agrees with him, calls him wise, and meekly defers to him on some point. He puffs up and as he leaves, he starts wondering if she is ill. What else could explain this submission.

Ruso has his own moments. When an accident causes injuries on a building site there is the competent legion doctor performing triage, applying tourniquets, snapping dislocated bones back into place while the dust is still flying. When quiet returns so does the self-doubt, regret, and weakness that dog his steps.

Tilla may be small and foreign, but she has learned to survive, as some heavies come to extort money discover to their regret. As she seems to drop to her knees to beg mercy, she is achieves the angle of attack!

Ruth Downie

Ruth Downie

This is the latest in a long running series. The learning is worn lightly but there is a mountain of historical research in each book that is made intelligible to the reader. It must difficult to maintain the momentum and to reiterate the freshness and vitality of the two principals each time, but so far, so excellent.

The author starts with a blank screen and the silent expectations of readers. The days and months pass and finally there is a plot, a story, and a manuscript. Then the real work begins of whacking it into a novel.

After all that work, one reviewer on Good Reads has this to say:

‘A non-offensive and not super engaging story about the Medicus and his family in Rome. It was a fine time passing book, but not one I would recommend.’

I would give that remark one star (*) and say it is lazy, inept, and self-indulgent. To sum it up in English: ‘An inoffensive story that did not engage my attention but I did read it.’ This reader’s recommendation is something I can live without.

‘Skeletons in the Closet’ (2011) by Jennifer Hart.

This is the first title in series ‘The Misadventures of the Laundry Hag.’

Maggie Phillips, a Georgia peach transplanted to Taxachusetts, is a domestic engineer to her retired Navy-man husband and two growing boys. Neal, the Husband was a SEAL, and knows a thing or two. He works IT three twelve hours shifts a week, leaving him plenty of time to pitch in when Maggie needs help.

Boredom with the duties of domestic engineer and the need for more cash than the navy pension provides, these together lead Maggie into business of house cleaning for the rich and fatuous around Boston. There she finds a closet…..

They moved to Boston because Neal’s parents practice law there: His father with patrician indifference and his mother with furious determination. When these two invite themselves, and their own guests, to Thanksgiving dinner with Neal and Maggie, the pressure cooker goes on. The parental guests are important clients of the mother-in-law and she demands that all be perfect. The father-in-law just likes to watch the mayhem.

It is a nice set up and despite the context, mercifully free of catalogue descriptions of all clothes and furnishings except where they figure in the plot or distinguish a character. There is plenty of repartee, and some of it is clever.

Jennifer Hart

Jennifer Hart

Maybe the mix is too rich with the wayward brother bobbing up and the boys; schoolwork. Yes, life is like that but fiction needs focus.

I listened to it in an Audible production. The accents sounded authentic to me.