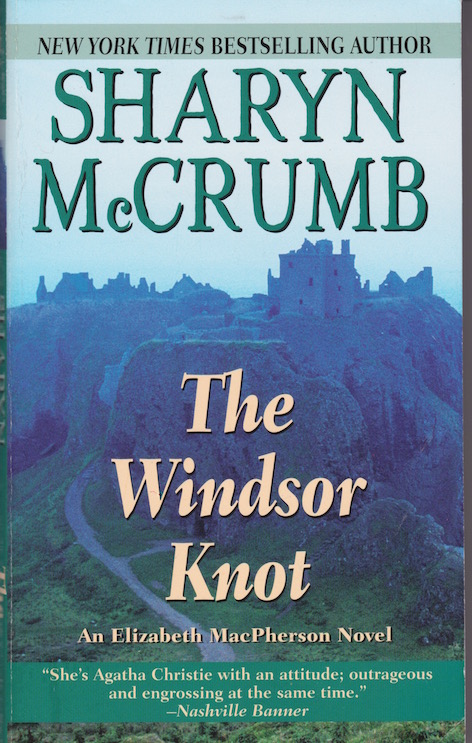

This title is a krimi set in contemporary rural Georgia in the borderlands with South Carolina and Florida in a small town whose chief denizens are the Chandler family. Belay those stereotypes!

The Chandler sons are an actor of great ambition and little talent, and a physicist who is proud member of the nerd fraternity. Captain Grandfather spend forty years at sea in the navy. Aunt Amanda, had she been available, would surely have repulsed General Sherman at Atlanta with her wit, skill, forceful personality, and the endless supply of contacts in the right places.

Returning to this fold is niece Elizabeth MacPherson, a forensic anthropologist, to be married in the ancestral home. Her unreconstructed hippie parents continue to smoke dope in Hawaii, trusting all arrangements to the Chandlers in residence.

Her beau is a Scots marine biologist; they pass the time with discussions of decomposition rates of flesh.

The plot thickens when local Emmett Martin dies…for a second time. I will say no more to spoil the plot. Suffice it to say it is clever, rIght down to the Biblical nomenclature.

McCrumb is a dab hand at delineating a cast of characters as individuals from all those named above to the several sheriffs and deputies, the scientific colleagues of each of the principals, and the townspeople, including the whole-earth tree-hugging tofu-eating caterers for the wedding whom Amanda suborns into serving flesh. Even the Queen of England and a princess make an appearance!

Sharyn McCrumb

Sharyn McCrumb

This is the second in the series centring on Elizabeth MacPherson, and I will lay in the first. However not sure about continuing thereafter. With neither zombies nor bimbos, it does not reach the heights of the other books of hers I have read. Being a one-woman industry she also has several other lines of fiction.

Agatha Christie said the secret to finishing was to start. McCrumb got the message.

Category: Krimi

Jarkko Sipilla, ‘Cold Trail‘ (2007)

A krimi set in coldest, darkest Helsinki in February. It is part of a set of titles called ‘Ice Cold Crimes’ with a set of authors from Finland.

It is a police procedural with much about the to’ing and fro’ing of the members of the Homicide Squad, set into motion when a convicted murderer escapes from custody. Intersecting with this low key pursuit is a traffic accident in which Lieutenant Kari Takamäki’s son is slightly injured, and he cannot help but intervene in this routine matter. There are also glimpses into the private lives of a couple of other officers, but the focus is mainly on the fugitive and his past. That is all to the good for this reader.

There is quite a lot of Helsinki in it, the streets, squares, buildings, residential high rises, the weather along with the organisation of policing, intelligence, SWAT,etc. The touch is light but definitive.

While most of the team is out questioning the one-time associates of the fugitive, one officer is assigned the homework of reading through all the files on the murder that led to his conviction and sentencing. In time, she begins to wonder if Timo Repo, the fugitive, was guilty, unpleasant, yes, but guilty, not so sure. To say more would be a spoiler.

Suffice it to say that the plot is well done and it ties together all the pieces of the story nicely, while delivering a few well deserved lashes to the unscrupulous news media and the perfunctory way unpleasant people like Repo are treated by lawyers and judges once they lay hands on them.

The book cover with that soft toy rabbit and the bloody hand have nothing to do with the story, as far as I could tell, but I did read it in bed as I was falling asleep….

While reading it I compared it to the latter volumes in Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö’s Martin Beck series as they descended into hysteria, mistaking their own ever greater self-righteousness for social criticism. By contrast, this volume is much more straightforward. All to the good. The police officers do their best, and in some cases that is not much, but in others it is more than enough. At the end when the SWAT team is set to go in hard and fast, its members would much prefer not to have to go. Too many guns and too much shooting is not the best or only way, they above all, know this.

Jarkko Siplia

Jarkko Siplia

Sipila has at least three other titles and in time I will get to them.

Bourne Morris, ‘The Red Queen Run’ (2014)

This krimi is the first of three involving Professor Maureen ‘Red’ Solaris in a college’s school of journalism. The dean of the school has died in a fall down some stairs over the weekend, Did he stumble or was he pushed?

There are many tensions within the school. The Old Guard is mortally jealous of its ancient privileges and prerogatives which the dead dean was eroding in reorganisations. Disappointed and disaffected candidates for tenure seem to be bent on destruction. Meanwhile, among the students, blackmail might be the route to an A+ result. Then there are the sexual assaults, divorces, and alcoholism. All and all, it sounds like a typical department. The only things missing, I thought, were embezzlement and extortion.

In fact, I found it all so real that flipped the pages, it being too much like being back at work: The special pleading from junior faculty, the one-eyed demands from senior professors, the requests of students for yet more concessions. If I wanted that, I could go back to work. It all seemed plausible, but that did not make it any more diverting to read. The only unrealistic element was the consideration and support offered by the corporate management at the top of the college to the beleaguered acting dean.

Professor Solaris is designated acting dean, and becomes involved in the snail-like police investigation. She then confronts the many psychopaths among the faculty and sociopaths among the students. At some point, I said a plague on all their houses.

Flipping the pages was made easier by the rather self-centred telling. The author identifies completely with Red and it shows. Her thoughts are cherished. Her love life sends quivers through the pages. Her fastidious habits are detailed. Oh hum. To this reader all of this was self-indulgent padding that advanced neither character or plot.

Bourne Morris

Bourne Morris

Not rushing to try volumes two and three, I am afraid.

‘Zombies of the Gene Pool’ (1992) by Sharyn McCrumb.

After reading her ‘Bimbos of the Death Star’ it was only a matter of time until I got around to ‘Zombies of the Gene Pool.’ When my Amazon Wish List came true on Christmas the time was right. It is an amusing and diverting lark as literati Marion and engineer Jay combine forces once again to get to the bottom of a mystery.

When frail Professor Erik Giles asks Assistant Professor Marion Farley to accompany him to a private reunion the fun begins. Jay Mega goes along to ride shotgun.

It is a very special reunion of a select group who were nutcase sci-fi fans in the distant 1950s. In the ensuing forty years some have made it big in books, in movies, in life and others have remained adolescent into old age.

The lore of fandom and tales of conferences past, the parade of sci-fi names, this book has it all.

Then one of the reunionist dies and the plot thickens. The old tensions and rivalries in the merry band emerge perfectly preserved in the amber of time. Secrets, long held and forgotten by some, seep out. Not good. The death was murder. Who done it? That is the question, Mr Spock, and the duo get to work on it tout suite.

With the schizophrenic Mistral leading the pack, along with the semi-comatose Surn, and the one-man avalanche Woodard, the phlegmatic Angela, the absent Earlene, lawyer Jim, the author has assembled a mix of folks and stirred the pot. The plotting is simple but clever, the dialogue sharp, and the setting vivid. Would that I could say even one of those things about most books.

The major theme is the disjunction between the expectation of fans and the reality of writers.

Sharyn McCrumb, who has many more titles to her credit.

Sharyn McCrumb, who has many more titles to her credit.

There is one glitch: when the hotel manager thinks of the death as murder long before that has been established on page 175. He of all people would certainly has assumed that the old coot died of natural, old-coot causes.

The book has pace, place, and plot. Four stars.

Spoiler Alert! There are no zombies. There were not any bimbos either.

‘McGarr and Sienese Conspiracy’ (1977) by Bartholomew Gill

This is an early title in a long running series.

It is model of composition and structure, covering a vast amount of territory in few words.

A body is discovered in far Dingle at the southwest tip of Ireland, trussed, drugged, and shot in the head like an execution. McGarr travels from Dublin Castle to investigate. Only two days later, while the usual inquiries are underway, a second body is found in the same place, the police tape and seal having been ripped off to dump a second dead man, likewise trussed and shot.

McGarr takes this second murder as a personal affront.

The victims were both English and that takes McGarr to London. The prime suspects are involved in oil expiation off the Scots coast, both Italians with ENI, and that takes McGarr to Italy, and eventually to Siena.

The characterisations are vivid, the travelogue nicely done, and the dialogue credible.

To this reader there is too much of McGarr musing on the English and the Italians. Too much description of clothes and food in both places as well as Ireland. All padding which does little, if anything, to establish either place or character. Too much to’ing and fro’ing. And it is beyond credibility that police in England and Italy defer to McGarr like a demigod.

I would have much preferred more of Ireland. For Italy I can read plenty of Italian krimis which will be mercifully shorn of musing on Italians.

The denouement was pretty obvious and so contrived as to be boring. The involvement of Foster, the Jamaican, seems gratuitous. The helicopter flying woman is another red herring too far. Just by coincidence she flew nearly the same route on the same days with one of the same passengers, who seemed to be two places at once.

Bartholomew Gill

Bartholomew Gill

McGarr also muses about several women, and this, too. I found a distraction, all rather adolescent. One of these women, later in the book, is called not once but two or three times by the first name Graham. It is a typographical error, that being her husband’s name. Talk about distracting. I thought at first he had come back to life. A sentence that contains ‘she Graham’ should have alerted any proof reader.

‘Honeymoon to Nowhere’ (1965) by Akimitsu Takayi

A Japanese krimi set in Tokyo. It offers a window on the manners and mōres of Japan in the 1960s. The obedience to parents of marriage age women and also men is part of the plot as is corporate loyalty. There is some by-play between the investigating police office and the prosecutors that reveals their differing agendas.

A few of the stereotypes are punctured, because there is corporate disloyalty, resistance to parental wishes, tax avoidance and these features must have made the book unorthodox at the time.

The description on Amazon made me think it was a police procedural, but the first 40% (I read it as an e-book so I noticed the percentage) is about the girl, her betrothal, and marriage and then her husband is murdered the night of their wedding. Before we get to the murder we learn much of her life, previous boyfriends, the effort of her parents to steer her to a suitable match, the one boyfriend who will not let go, and the courtship of her husband. Oh hum.

Even with the dead body, there is far too little action for it to be procedural. Mostly the police officer and prosecutor sit around speculating on what might have happened without a shred of evidence to guide their thinking. When evidence kills one line of speculation, rather than pursue more evidence they retire to speculate more. Oh hum. Wordy.

The plot is well developed and wraps everything up, but I am not sure how many readers will persist. I did, and that is a tribute to the ingenuity of the plot, not to the action or to the vividness of the characters, whom I had trouble keeping straight.

Akimitsu Takagi

Akimitsu Takagi

The author has several other krimis in print.

‘Bellringer’ ( 2012 ) by J. Robert Janes

An intriguing set up for our very weary duo.

Before the war, the luxury spa hotels of Vittel hosted the wealthiest members of French and international society. Now, in the winter of 1943, two of these hotels hold British and American women, the former since 1939 and the later since December 1941. The prisoners had lived quietly, surviving on Red Cross aid packages, but now they are beginning to die.

One American woman died in a fall down an elevator shaft, and it was assumed to be an accident, then an unknown assailant stabbed another to death with a pitchfork in the stables. With the second death the commandant calls for help, and inspectors Jean-Louis St-Cyr of the Sûreté and Hermann Kohler of the Gestapo arrive. In the pockets of the second victim they find Cracker Jacks and Hershey bars — presumed to be bribes for the guards. St-Cyr and Kohler have to unravel a conspiracy that is at the heart of this odd arrangement.

Above is an edited version of the blurb on the Amazon web site which seemed to me to be both inaccurate and overblown. No Germans stormed into Vichy. The two groups of women are in separate hotels and that is part of the plot, and they have been incarcerated for different periods of time. Whatever the past of the hotels, there is no luxury to be found there. Nor does it make sense to call a hotel a camp. The garbled blurb is very like Janes’s prose. I have read many of the titles in this series but the prose is leaden.

Janes does a good job of distinguishing among the women. There are many different stories among them, and in fact, some of the inmates are French married to Brits or Yanks but with the wrong passports when their papers were inspected. Their individual hopes, aspirations, methods of dealing with the privations and boredom are well brought out, like clutching at occult straws. Confined and controlled for years, there are endless frictions, grievances, and complaints which, powerless to affect the casual agents, the Germans, they take out on each other. There are tensions between the two nationalities, and even more within each.

‘These papers are not in order!’

‘These papers are not in order!’

By the same token there are tensions among the German guards, who would rather be there than in Russia. The commandant who called in the investigators has been undermined and replaced by a subordinate who wants no investigation.

Most of the investigation falls on the American hotel, many of the occupants of which are students who were doing courses in France when the curtain fell.

The grey prose, the cryptic descriptions, the gnomic interpretations, the ambiguity of voices, they all combine to obscure the denouement. But then I read these for the atmosphere, not the arrival. Once again the pair prevail despite all the impediments.

‘Atmosphere’ I said. For example, the privations of the Occupation. Everyone is hungry, and have lived for so long on a poor diet that their senses are diminished, they have no stamina, and cannot concentrate. Nor are the German jailers much better off.

Michael Gilbert, ‘The Etruscan Net’ (1969).

‘A very smooth and entertaining tale of adventure and intrigue in Florence shortly after the great flood. Art objects form the centre of the crookedness, and the social and political entanglements are done with a sure hand, together with a few persuasive characters. The suspense is light.’ From ‘A Catalogue of Crime’, eds. Jacques Barzun and Wendell Taylor.

Occasionally I select a title recommended by Jack and Wendy and this was one. It was readily available in 2004 reprint. Everything in the comments above is true. Alas, it is also true that I tired of it about half-way through. My failing, no doubt.

I liked the characters, the retired British naval man whose instincts help navigate the troubled waters, the indifferent victim, the forthright housemaid, Mercurio the odd ball adoptee, they all livened up the pages. The method of implicating the victim with his car was new to me. I also read with interest the soupçon of Etruscan art mentioned, and wished for more. How the Etruscans related to ancient Romans is one of those recurrent questions when I read about either, the more so having once seen some Etruscan ruins and art while resident in Firenze at the European Universities Institute. I also know that Decius never trusted any Etruscan, real or imagined. alive or dead.

But the plot quickly descended into yet another rendition of the total corruption of Italian society, from the building janitor, who for a few lira will let the Mafia killers into the apartment, to the traffic warden who for a few lira will wheel clamp any car, to the tax collector who for a few lira will raid the office and impound books….. no questions asked. Our heroes are up against a total conspiracy of a kind to make Stalin envious.

Yet somehow our heroes do prevail but by then I was turning the pages so fast that the detail of how escaped me. There were several villains involved and perhaps they came into collision for there is no honour among thieves, I suppose.

Lawyer by day and writer by night,

Lawyer by day and writer by night,

The author is very accomplished and industrious for there are many other titles. I might try one of the series because I like continuing characters.

‘When the Bough Breaks’ (1985) by Jonathan Kellerman

The first in the series.

Alex Delaware is a psychologist who is gradually drawn into police work when a child abuser commits suicide in his office during the night. Delaware had been working with the victims of this perpetrator. That event jarred Delaware loose from his profession, his clients, his positions, his habits and much else. At the same time it also opened the door to helping the police with inquiries, in that quaint British expression.

In this case, a fellow psychologist has been murdered along with his girlfriend, and while Delaware did not know the man personally, there is a professional interest and then a police officer asks for his assistance in questioning a seven-year old child who is the only witness to event in an apartment complex in Los Angeles. ‘Questioning,’ as we learn, is not the right word, but rather finding out what the child, now very frightened, saw and then interpreting that. The child arouses his sympathies and he is hooked. If it sounds rather contrived, it is not in the reading.

I particularly liked his long interview with the curmudgeonly emeritus professor who enjoys dishing the dirt. If only…. The description of the rainstorm charged by lightning was very fine, though by then I was impatient to get to the point.

The killing of the dog was too much. Every woman Alex meets is attractive and attracted to him, but he manfully remains loyal to Robin. Tedious.

All of the pieces do fit together in the plot, though it is far-fetched, but then again maybe not. Reality is sometimes hard to believe, too.

There are thirty or so Alex Delaware krimies that I have never read, despite my taste for police procedurals. It came to mind when I recently heard a Garrison Keillor ‘The Writer’s Almanac’ podcast in which he mentioned Kellerman’s long road to publication. Ten years of typing away three hours a night in an unheated garage in New York and stacks of rejections before the first publication.

By the way, this is my third Kindle book reading.

‘Henry Wood Detective Agency’ (2013) by Brian Meeks

The first in a series of self-styled noir mysteries set in January 1951 in the Big Apple. A very easy read with many short chapters and some interesting characters, and then there is that closet which, like Henry, I thought was going to be explained and wasn’t. I kind of liked that. There was also plenty of woodworking.

It is at once very conventional and somewhat unconventional. The tough cop. The honourable criminal. The femmes fatales, who turn out to be OK. But mostly it is connect the dots. There are some bons mots but it does not crackle.

There is no tension and the characterisation is left to the woodwork. Too many chapters started with a new character who proved to be ephemeral anyway.

The rapprochement between the food critique who has an office nearby (and not at the newspaper for some reason) and the tough cop is not convincing, not interesting, and not relevant. They will probably appear in later titles in the series.

The mystery is that closet where occasionally Henry finds gifts from the future for both his hobby of woodworking and his job of detecting. That and Bobbie the motor-mouth estate agent who seems to know Henry’s business better than he should.

Brian D. Meeks

Brian D. Meeks

Left me unsure if I want to read another one in the series.

I read it as a Kindle book. My second.