William Donovan (1883-1959) was a lawyer, an Irish Catholic, Federal Prosecutor, bootleg buster, speakeasy raider, Assistant United States Attorney General, and a life long enemy of Hoover J. Edgar. That latter alone seemed recommendation enough. But wait there is more. He also created the Central Intelligence Agency in all but name. How he came to do that is quite a story.

The O’Donovans left Ireland in the 1840s for Montreal, and from whence to Buffalo which was a boom town, thanks to Great Lakes shipping, the Erie Canal, and the railroads going west. They shed the ‘O’ to become Donovan, and one of the grandchildren of the migrants was William. He grew up in Buffalo which was still booming and bustling at the end of the Nineteenth Century.

Thanks to the encouragement of a local priest he was well educated and did a Bachelors degree at Columbia University in New York City, and then a law degree there, where he was a classmate of Franklin Roosevelt. Sitting in the same lecture hall, they were worlds apart. Donovan was bog Irish in looks, manner, and attitude, while Roosevelt was aristocratic, aloof, and condescending, the former knew he had to work for a living, while the latter was driven around by a chauffeur who sometimes carried his books. Their paths would cross again.

Leaving aside the details, Donovan went back to Buffalo to practice law but he found it boring. When married, he and Ruth did a world tour and that ignited the wanderlust never to be abated. They went to Tokyo, Paris, Rome. Thereafter he kept a suitcase packed and carried his passport ready to take off again. When, during World War I, Herbert Hoover started food relief in Belgium, Donovan volunteered to work on it, and in 1916 he was Berlin with a party negotiating passage of food to Poland. This trip was at his own expense, a practice he followed thereafter, paying his own way.

Earlier he had joined the National Guard in Buffalo, partly as a way into the upper echelons of Buffalo society. When the United States entered the war, he became a Colonel of the infantry, where he got shot up and walked with a limp ever after. That was when he got the nick-name ‘Wild.’ Though he was later promoted to general at a desk, out of the army he preferred to be called Colonel after his combat service.

He was much medaled, more so than Douglas MacArthur, and that rankled the latter ever after.

After the war, a Buffalo celebrity, he became the Federal Prosecutor in a city infamous for it bootlegging and the many blind-eyes turned to it. He took the blinders off and enforced the law with the same energy and fearlessness he had found within himself in no man’s land in France. Since much of the high society of Buffalo financed the illegal alcohol trade with Canada, he prosecuted many of the social and financial elite, including eventually his own in-laws. He had warned them, but they refused to believe he would touch them. Wrong! Thereafter, he was ostracised in Buffalo, and his wife soon started leading her own, separate life, as did he.

By the way, he seldom, if ever, drank alcohol himself. His failings did not include hypocrisy.

He went from there to Washington D.C. as an assistant attorney general, where he was equally vigorous, so much so that he made an enemy of Hoover J. Edgar, who opened a file on him, one never to be closed. Donovan’s many prosecutions of criminals deprived Hoover J. Edgar of the limelight and he hated that. It also upset some of the arrangements Hoover J. Edgar had with organised crime figures, we now know.

Donovan had hoped that incoming President Herbert Hoover would appoint him attorney-general but it was not so, perhaps because appointing a Catholic to the post was not a confirmation fight President Hoover wanted, perhaps because Hoover J. Edgar was finding dirt and there was some to find, and slinging it. Disappointed, Donovan quit.

He was a lifelong Republican, and ran for lieutenant governor of New York against a Democratic ticket led by Franklin Roosevelt. While Roosevelt treated him with the amused indifference of the landed gentry in this contest, Donovan was tense and desperate to prove himself. He failed. He tried again in 1932 as the Republican candidate of governor and failed again in the face of the Democratic landslide of that year.

But in this period the most important point is that he travelled extensively in Europe and Africa. He became an unofficial go-between, agent, and observer. He was in Berlin in the 1920s and saw a young Adolf Hitler speak who, like a priest, sometimes stood at the exit door, and shook hands with those leaving. In this way Donovan shook hands with Hitler. Imagine how Murdoch’s organs could distort that today.

When the U.S. Army failed in its diplomatic efforts to get observers placed with the Italian Army in Ethiopia, intermediaries convinced Donovan, as businessman, to go and observe, he took little convincing. He travelled at his own expense to conceal the government interest. To get permission to enter Ethiopia, Donovan went to Rome and had an audience with Il Duce whom he flattered into signing a visa. Off he went. He later reported to Washington contacts.

In the first ten years of his marriage to Ruth he spent, in total, eighteen months with her, and some of that was travelling time, too. His frequent traveller miles must have added up to millions.

There were many other trips, and each time he would report what he had seen to army contacts like MacArthur or Washington Republicans. MI5 in England marked him as an agent of influence and began to cultivate him. He soon became an unofficial, informal conduit between MI5 and the government in Washington.

Donovan, by now, was part of loose association of businessmen and journalists in New York City who appointed themselves observers and intelligence agents for the United States government in their travels. That sent him off on other self-initiated and self-funded assignments. These expenses and the costs of the lavish life he lived when in the States were considerable and caused much tension with Ruth, his estranged wife, but that did not slow him down.

While he loved the coming and going, he also learned and said that much more important information could be learned by compiling and reading files than watching elevators traffic in hotel lobbies. His emphasis on the intellectual side of intelligence work, as opposed to field work, would become a distinguishing feature of the OSS, though little of that is recounted in these pages.

As the war clouds moved toward the United States, Donovan got a call from the Secretary of the Navy in the Franklin Roosevelt administration, Frank Knox, a rock-ribbed Republican. Knox commissioned Donovan to go to England and assess its capacity to endure a German invasion. Off he went, at his own expense, filling his notebooks with a code he had devised for himself in earlier travels, and came back to write-up a three hundred page assessment. He was hard-headed about it but positive: England would endure. It was a conclusion to which he was coached by MI5 and MI6, but which he also genuinely believed. That led to other such assignments, in the Bahamas, Canada, in a kind of drawn-out job interview and test.

Finally, Roosevelt asked him to assess the intelligence services of the United States government. This was releasing a fat boy in a candy shop. It is a long story but the short version is that there were a number of competing agencies that jealously guarded their zones and prerogatives, and did not share information. There was Army Intelligence, there was Navy Intelligence, there was the State Department’s Information Service, there was, most of all, the Federal Bureau of Investigation. There were other, second order, offices, directorates, and agencies. They each gathered and compiled reports. Moreover, within each of these agencies and offices there were further divisions, rivalries, and conflicts. No one had access to, let alone read, all the information generated, and it was wildly uneven. Each tried to report directly to the President, and each, in the pursuit of budget, devoted much time to disparaging the others and interfering with each other. Anyone who has worked in a large organisation will be familiar with this pathology.

The most pathological of all was, no surprise, Hoover J. Edgar. He kept adding to his file on Donovan, mostly about women.

Donovan proposed, first, an agency that would oversee and centralise the findings of all the services. Any Vulcan can see the logic of that but it led to a colossal bureaucratic war, which he lost. The intelligence services would not combine nor cooperate and they would never share information, but they did briefly unite to stop the creation of any new supervisory intelligence service such as Donovan had recommended.

Still Roosevelt liked what he saw from Donovan — the energy, the optimism, the audacity, the aggression — and found a role for Donovan, first as director of the Office of War Information, where he hired playwrights (Robert Sherwood) and film-makers (John Ford) to create propaganda, thereby offending journalists who thought they should have had the sinecures. Thereafter, the press never missed a chance to denigrate him.

Donovan also believed in research, though quite where he developed this conviction is not explained in these pages, He set up offices in the Library of Congress and hired experts in area studies like North Africa, for example, Ralph Bunche who is not named in this book. He also hired women as researchers and paid them over the going rate, but did not promote them to positions commensurate with their abilities. As far as Hoover J. Edgar was concerned hiring black men like Bunche and paying women higher salaries were criminal acts and his Donovan file grew. He never missed a chance to blacken his name in the constant backstage back-stabbing that makes Washington D.C. go around.

Since Donovan’s was the new boy, the established agencies declared his operation to be amateurish, and thus untrustworthy. Secrets were withheld from Donovan because he could not keep a secret they said. He then set about a campaign to prove a point. He invited his chief critics to lunch, where he invited them to air their criticisms about his sloppy security to him. They did. Then at the end of the lunch one of his assistants would appear and hand him a file. In it would be copies of some super-secret documents from the critic’s office which had been earlier purloined, accessed, photographed and replaced by one of Donovan’s amateurish agents unbeknownst to the smug critic and so deftly no one in the interlocutor’s office from when it came noticed it had happened. He would, without a word, slide the file across the table to the critic. He thus privately humiliated four or five leading critics, who then redoubled their efforts to destroy him. However it paid dividends because it was an exercise that made him legend among his own staff. Wild, indeed. He would stop at nothing.

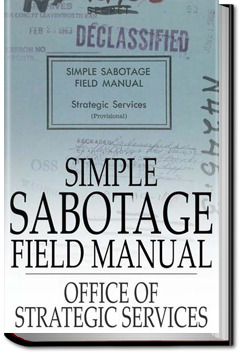

In short order, Donovan had thousands of employees, many doing research on the ground in Portugal, Spain, Bulgaria… Thus born was the OSS, first the Office for Special Services, and then the Office for Strategic Services: espionage, sabotage, propaganda, and the like.

He did win the most important bureaucratic contest in that the FBI was confined to United States territory as a counter-intelligence agency, while the OSS had the world. This is a parallel of the distinction between MI5 and MI6 in Great Britain. Hoover J. Edgar never forgave him. They then argued over whether foreign embassies in D.C. fell under the OSS or the FBI. At least on one midnight occasion OSS and FBI agents ran into each other while burgling a foreign embassy on Massachusetts Avenue. All very KeyStone Kops.

The difference was this. If the FBI wanted something, it was done the American way. Kick-in the door and take it. This approach to foreign embassies in D.C. had quickly infuriated the D.C. police who were blamed for not catching the burglars. If the OSS wanted something, there was subterfuge, subversion, and suborning which took longer but left few traces. The OSS developed many spy gadgets to do these things. To Hoover J. Edgar the OSS approach was effeminate.

It is easy to see where the Special Relationship on intelligence arose per ‘The Sandbaggers.’ In the earliest days, Donovan copied the British example, and the Brits fed him intel in order to influence and tame him, while he milked them. Indeed for a time many in D.C. regarded him as a representative of British interests, since he parroted their line, e.g., on the invasion of the Balkans.

But he had many struggles with the British, too. The details are moot, but the conflicts of interest were real.

The OSS efforts to reduce Vichy resistance to Operation Torch were many but to little effect. But at least the OSS did not truck with Vichy, as many other Americans did, even while the Vichy Administration in Algeria deported Jews to German death camps with the complicity of some American diplomats. The author seems unaware of this bad business.

While the British Special Operations Executive was inactive in some of the territory ceded to it in the papal division of the world the two agencies had agreed upon, it would not tolerate an incursion by Donovan. The Brits may have done nothing in Rumania, and have no plans ever to do anything, but they would not tolerate an OSS operation there. Never!

While the war was being won and lost in Russia and later in Normandy, the SOE and OSS were besieging their respective chiefs of staff and prime minster/president with memoranda by the score about who had exclusive rights to launch sabotage operations on Corsica and on Sardinia!

Despite Donovan’s efforts and those of his field agents, many of whom were killed, the Office for Strategic Services seems to have had little, if any, strategic effect. At a tactical level some of its projects did payoff.

One of his most significant personal contributions was to convince the Nuremberg chief United States prosecutor to call victims as witnesses in the crimes against humanity trials. That prosector had planned to argue the case by reading facts and figures from German records and those Germans who had confessed to their part in it. Donovan argued that the victims had a need, a right, to confront their demons and say their piece for eternity. When the prosecutor came around to the tactic, Donovan turned his field agents loose on finding such victims of the death and labor camps. Their harrowing testimony is forever with us. Thanks be to Wild Bill Donovan.

While much of the book details Donovan’s efforts to insert OSS agents into Sicily, Sardinia, and Italy, not a word is said about the American organised crime gangsters who facilitated the entry and the sweetheart deals made with them. Those deals began a long-running association of the American mafia with the later CIA. On this very distasteful story see James Cockayne, ‘Hidden Power: The Strategic Logic of Organised Crime’ (2016).

The book charts much more of Donovan’s many trips and the missions he sent, but none yielded much success. There is no doubt, Donovan had a great deal of wit and energy, but the OSS was a chaotic organisation, badly run, lacking focus, seldom disciplined, often more interested in show than go, and constantly preoccupied by the rival intelligence agencies in D.C.

Though in some asides, we learn that the research done in D.C. by the OSS was done well and was very useful, but we get little on that and more on Donovan’s diet than whatever he did to establish and develop that analysis. Readers of the ‘Pentagon Papers’ will recall that the CIA was an honest analyst in those pages, unlike G2 Army Intelligence, State Department Information, Navy Assessment, and NSC briefs. These others were unfailing optimistic and upbeat following the political wind, with a little more effort (i.e., more mayhem and murder) and the Vietnam War will end in triumph. Only the CIA was Cassandra each and every time, and right.

At the end of World War II in 1945, President Harry Truman shut down the residual New Deal agencies, and those created for the war effort, one after another, as quickly as possible to return to normal life, and that included the OSS. Donovan had tried to redirect it first at counter espionage regarding the USSR in the USA, but Hoover J. Edgar stopped that. Donovan then tried to target the USSR but found that hard going.

In 1947 the CIA emerged from the analytic efforts that Donovan had started, but quite how is not the subject of this book, but another by the author.

One of those desk bound exports was the manual conveyed to occupied Europe on how to disrupt the Occupier without personal risk. I note especially the part about using participation on committees to slow everything down, and how managers can slow things done. These manuals must have been the basis of Telecom.

‘Wild’ Bill Donovan is a name I have known for years. When and how I learned it is lost in the mists of time and tide. Reading biographies of others from the 1940s and 1950s, his name cropped up. It seemed time to find out more.

The book is written in the annoying style of newspaper journalism. Each chapter, and many sections within chapters opens with a hook sentence, e.g., ‘The telephone rang at midnight and the caller said..’ Then it back fills to get to the phone call, usually. I say ‘usually’ because a few of these hooks seem to be forgotten and go unexplained. It means each time the narrative is interrupted and resumed, like stop-start traffic. It jumps around so much I wondered if some of the dates were wrong. No doubt, this method of exposition is what makes it, per the cover, fast paced. It also made it, at times, unintelligible to this reader.

Douglas Waller

Douglas Waller

It lapses into clichés far too often. Opponents are gunmen who gun down innocents. One-eyed and simple-minded more than once. No doubt these clichés are what make it exciting, per the front cover.

I turned a lot of the later pages quickly, having long lost interest in Donovan’s travels, dinners, and handshakes, and his sometimes naive efforts to exert influence in China and elsewhere. These details tell the reader nothing about the man.

Category: Leadership

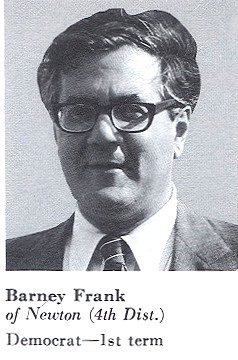

‘Barney Frank’ (2009) by Stuart Weisberg

Barney who? Barney Frank, the nemesis of many a blowhard on Capitol Hill where they flourish. He was often to be seen on C-SPAN boring into witnesses, preferably a stooge for a vested interest like automobile manufacturers demanding more subsidies, junk bond owning banks there to defend executive bonuses, or a Republican administration flunkies sweeping dirt under carpets. He went at each as the prosecuting attorney cross examining a well-known villain.

Only the most truthful and well-prepared witnesses limped away intact.

The Frank Test became a coin in Congress for thirty years. If Barney Frank could not find fault, then it was good to-go.

Mr Frank was born in 1940 in Bayonne, New Jersey where his father owned and ran a truck stop. His parents once hosted a reception for Eleanor Roosevelt in their home when he was a boy. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1981-2013. He basked in the label, ultra-liberal.

His political career began when, a graduate student in political science at Harvard, he got involved in Kevin White’s mayoral campaign in Boston. Frank, whose graduate work was not compelling, found politics very compelling and worked night-and-day for the White campaign, and emerged as one of its masterminds. He was always there, always picked up the phone, always remembered someone who could help, always found what was lost, always thought of something to try… Reliable, dependable, creative, and accessible, he made himself invaluable.

When White became mayor he had obvious ambitions for higher office and spent most of his time in that pursuit. That left his de facto chief of staff Barney Frank in the office to take the calls and make the calls. (I say obvious because some time later when I spent a semester at Harvard on leave I observed the White administration from across the Charles River in Cambridge and White’s disintegrating ambitions were a spectacle.)

Frank found politics much more interesting than political science and did not complete the graduate degree. He took time off from city hall and worked for a congressman in Washington D.C. for two years and liked what he saw in the legislative world.

He kept solving problems at town hall, meeting more people, impressing others with his thick skin and tireless efforts. He ran for the Massachusetts state legislature, which has the quaint name of Massachusetts General Court, and won a seat in the lower house.

For eight years in the statehouse he advanced one liberal cause after another, e.g., low cost housing, abortion, civil rights, school bussing, and the like. Many people spout liberal causes and are satisfied with that, and Mr Frank, too, likes to spout, but unlike many others, when the spouting was done, he took committee work seriously and applied himself both the substance of reading and evaluating submissions, proposals, and evidence, and in learning the rules of procedure. He also employed researchers to dig and dig they did. Accordingly, he scored some publicity coups and some legislative successes.

A large, disheveled, left-handed Jew, representing a Back Bay constituency made good copy any time, and he attracted publicity. Plus he has a motor mouth, and a quick wit. On slow news days journalist knew they could get copy out of him, and he obliged on his terms. (The Back Bay is home to the purest, whitest, richest, most closed colonial aristocracy of Massachusetts. Upstarts like the Kennedys were barred from this society, having to make due with Brookline.)

At the time many liberals liked spouting about foreign affairs, but Mr Frank went on the banking and finance committees because that was where the money came from to fund liberal causes like low-income housing. The first thing he realised was that inefficiency and sweet-heart deals with labor unions made spending on liberal causes impossible. The first of his many crusades was to cut waste government where he made allies with conservative Republicans, and antagonised unions. The battles with the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority became legendary. He rode the MBTA every day and charted its many failings against its exorbitant running costs and outlandish work practices, outlandish even by Australian standards. His spreadsheets on cost per customer mile traveled compared to other cities entertained viewers on news programs for weeks on end.

He also accepted no-win assignments on other committees where his vote would alienate some Democratic constituencies, like organised labor, but since he had already alienated them, he did the duty, sparing other colleagues the pain. They then in turn owed him favours.

In the financial crises of the Junior Bush years he was a Cassandra, warning of trouble ahead to be ignored, and then later as the wheel turned he was blamed for causing the trouble by predicting it. In hindsight Republican Bush administration officials even blamed him for not stopping them. That is political logic!

There is no doubt he was a one-man brains trust in Congress with some memorable turns of the phrase who had no small talk and no time for normal pleasantries. He was always all business all the time, right here, right now. Nor was he easily discouraged: Blunt, direct, acerbic, and well prepared. Here are a few examples.

1.This bill is the legislative equivalent of crack. It yields a short-term high but does long-term damage to the system and it’s expensive to boot.

2.People might cite George Bush as proof that you can be totally impervious to the effects of Harvard and Yale education.

3.Moderate Republicans are reverse Houdinis. They tie themselves up in knots and then tell you they can’t do anything because they’re tied up in knots.

4.They have become so attached to their outrage that they are outraged to lose it.

5.Southern racists were able to protect murderers only because their legislators exploited fears of federal power.

6.For those like Ben Carson, who just announced that it was a choice, I do want to say at 14 I did not choose to be a member of what I thought was the most hated group in America.

7.They can vote for every possible war that comes along and still be pro-life.

8.The runner slides into home with a thousand dollars in hand as a contribution to the umpire but the money will not effect the call….that is what we say about campaign contributions.

9.I’m left-handed, Jewish, and Gay, there is no majority I belong to. Well, maybe the overweight.

When an amendment he presented failed in committee, he re-worked it and presented it again, and again, and again. In so doing, he became a master of procedure. He also spent all hours trying to talk others around to his way of thinking. This talk, talk, talk reminded a little of the loquacious young George Wallace.

The descriptions of the joint House and Senate committees to harmonise bills and of the ad hoc committees called by President Bush to find common ground are delightful. In them John McCain comes off as a driven man who knows he has to be involved but has nothing to offer and takes his own sweet time in doing that. Bush Jr appears well meaning but lost.

But the severest criticisms are for the technicians Henry Paulson at Treasury and Benjamin Bernanke at the Federal Reserve whose faith in their own technical prowess led them to overreach.

On the other side of the coin Senator Barack Obama comes across as extremely able, well versed, and ready to compromise if it will do some good. While McCain was determined to be the centre of attention and when he got it, he had nothing to say on the subject, Obama was content to wait his turn and when it came he make concrete proposals that most could accept.

Mind, the telling is entirely one-eyed and ever partisan.

Frank’s other claim to fame is the public acknowledgement of his homosexuality in 1987. It was a long time in coming but a few years before he began telling family, friends, and then colleagues. There were whispers and finally an interview was arranged in which he would be asked the direct question to which he gave the direct answer. The double-life he had been living for years was difficult he had eruptions of temper, often directed at women, including some journalists on air. He was losing self-control and had enough sense to realise it. It would be better, he thought, to clear the air and let the chips fall. This is the longest chapter of the book and more interesting. I flipped through many of the remaining chapters at light-speed.

For a time his private life became very public, and the news was not always good. He did some stupid things. Hands up all those who haven’t.

Frank seems to have found happiness.

Frank seems to have found happiness.

The book is replete with anecdotes and much play-by-play description which does nothing to illuminate the man and his formative experiences. Barney walks on water through most of it. I stress the uncritical nature of the book because it surprised me, coming, as it does, from a university press.

Stuart Weisberg

Stuart Weisberg

I chose it because of the publisher on the assumption it would be dispassionate and disinterested. Not so.

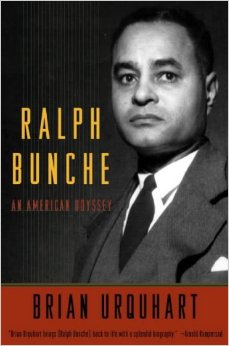

‘Ralph Bunche: An American Odyssey’ (1991) by Brian Urquhart

Heads up! Who was Ralph Bunche (1903-1971), and why do not you know? You do not know, now do you. Shame!

A few hints then. He was point guard on three conference championship basketball teams at UCLA. [Sounds of silence.] This was a minor part of his odyssey.

Another hint. He had a Harvard PhD in political science.

No, still nothing.

How about the fact that he got a Nobel Peace Prize, and in his case, unlike several other recent recipients, it was deserved.

A last try, he served in the OSS during World War II. Huh? I hear the thinking. Look it up, Mortimer.

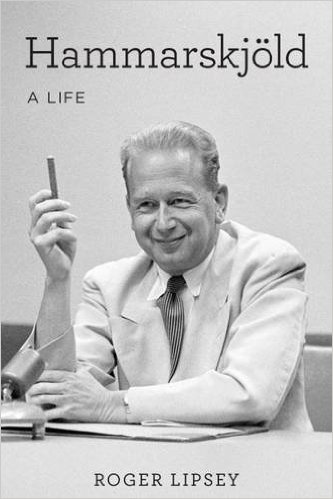

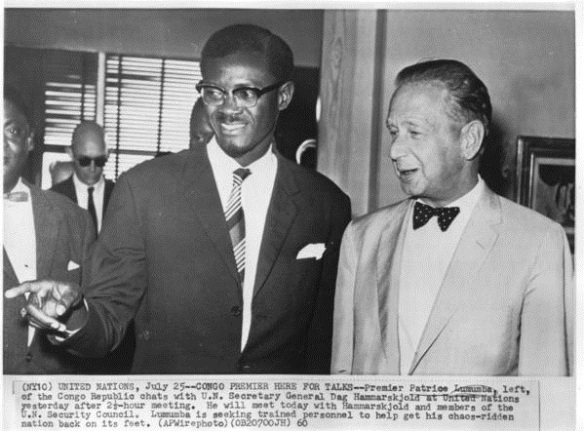

Let’s get the cat out of the bag. He was Dag Hammarskjöld’s right hand at the United Nations where he worked from 1944 to 1970. In fact, his tenure preceded Hammarskjöld’s and, of course, he outlived the Swede.

Oh, and he was an American Negro (the term he always used). That bespeaks the odyssey. His grandparents were born in the slave society of Missouri.

It was an article of faith from those grandparents onward on both side of the family tree that a black had to be educated to survive in the white man’s world.

Born in a Detroit before it became the manufacturing capital of the United States, his family moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico in the early 1915. Tuberculous was suspected in some family members and they packed off for the dry climate with a few dollars and strong wills to make a living. His mother and grandmother combined to insure that he got an education. When his school work was poor they complained to the school, where the principal rather thought they should be grateful that the school even took in a negro.

He was a bored student in high school, these two decided, because the school had slated him for vocational classes, woodwork, typing, auto shop, book-keeping. They more or less sat in the principal’s office until Bunche was put into the academic track of college preparation. They then applied themselves to making sure Ralph lived up to the challenge, and he did.

He encountered racism but only small doses in the sparsely populated New Mexico. The family moved to Los Angeles, as so many others had, to find the land of milk and honey, after the arid dust of the south west. He graduated from high school first in his class but was not recognised as such. Figure it out!

Yes, he played sports as boys do, and got a scholarship to play basketball at Cal.

Sportsman.

Sportsman.

Like many others he combined the gym with the library.

He was first in his class again but not honoured as such…because? See if you can guess. The school did not want a black face at the podium with all those benefactors and check books present.

The BA was not enough. He did the one true major, political science. His undergraduate supervisor encouraged him to do graduate work and he went to Harvard, first for an MA, and then a PhD. Along the way he had many part time jobs as students do, and each time he did his best to do them well. He knew that there was no margin of error for a black man.

The PhD made the man for he studied European colonialism. To do that his supervisor insisted he learn languages, French and German. His supervisor also secured funding for him to do fieldwork in European archives and in west Africa. Young, energetic, idealistic, and black he examined French colonialism in west African colonies some of which had been German. What impressed most him the most in his contemporary letters was the alcohol that French colonial officials put away. Second, was how sloppy the records in the archives in Paris were. Third, he found virtually no racism directed at himself in Paris, Dahomey, or Togo. At the time, he took it for granted but in latter life mused on the two-speeds of racism.

Howard University in Washington, D.C., a black college, created a political science department and appointed him the foundation professor and head of department while he was completing the PhD research. He was appointed ABD!

ABD? I was appointed ABD at Sydney. These days few people would be appointed ABD. ABD? All but dissertation. It means that a graduate student has completed all the requirement for the PhD but has not yet submitted the dissertation and had it accepted.

After a master degree with a thesis, the PhD requirements would include three years of advanced seminar work with many essays and research projects, then general written examinations (in three fields), and oral examinations over the generals. It would also include the preparation, defence in writing and oral tests of a proposal for the PhD dissertation. It is heavy lifting. But the heaviest lift is to come in the dissertation which takes about two more years.

But there are many stops along the way from ABD to completing the dissertation. ABD forms a continuum. At one end is as above, at the other is someone who completed all the research, written the dissertation and had it examined and passed, but the degree has not yet been awarded due to the cycle of the university.

To cut to the chase, many, many ABDs do not become PhDs. They do not complete that final requirement, the dissertation and defend it. Of these most just do not finish; only a few finish the dissertation but fail the final defence, though I have seen it happen twice in my forty years at the table.

There are as many reasons why ABDs do not finish as there are ABDs. Life intrudes, the fellowship runs out and a living has to be earned. Pregnancy alters priorities. It proves hard to conceive, execute, and write a book in the two years.

While ABD Ralph Bunche had his share of problems. His duties at Howard were demanding. and while the pay was adequate there was nothing left for more field-trips, to pay for professional typing, conference travel, or translations. But somehow, thanks largely to his long suffering wife, Ruth, he did it. In sum, he had all the problems any ABD had, and each was overlaid by the racism of the time and place. e. g., getting access to the Library of Congress was a struggle for a black man.

He got another fellowship for archival research, this time at the Colonial and Foreign Office in London and during this period he met a long list of others like Paul Robson, many of them communists to a degree, as the only recourse for black hopes. He found himself at home in this worldly milieu, but argued constantly against the communist line. He agreed that class incorporates race and was the origin of much racially suspicion, fear, and hostility in the white working class and lumpenproletariat, but he had no use for the Communist Party as an agent of change for the better. Of course merely talking to such believers made him a fellow traveller to the likes of Hoover J. Edgar. During this period, 1937-1938, he made an extensive field-trip to East Africa, including Kenya, where he made many contacts thanks to his London friend, Jomo Kenyatta.

When lights went out all over Europe again, the War Department began serous recruiting, and it wanted an African specialist, especially French North Africa. Bunche was recruited to work in that very same Library of Congress. Cognoscenti will know that the OSS was housed there initially because Colonel William Donovan wanted his agents to have a thorough grounding in culture, history, and languages. Yes, Bunche became a desk officer for the Office of Special Services, the parent of the CIA. He wrote manuals and training programs that were eventually used by American forces in Operation Torch, the landings in Morocco and Algeria.

He also attended at least one of the Roosevelt-Churchill summits which addressed the post-war world. President Roosevelt wanted planning for the post-war world to start from day one of the war, or before, and it was in fact before, because he had seen the aftermath of World War I descend into comedy, farce, and now tragedy.

When the idea of a new League of Nations to keep the peace emerged, the State Department wrenched Bunche from the OSS and put him to work on the future of colonial places and peoples. Bunche had become the United States expert on European colonies. He attended the San Francisco foundation of the United Nations on the American delegation, where he soon became the United Nations expert on colonies.

Mediator.

Mediator.

He also worked closely with Eleanor Roosevelt on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

He was a master of the research, also he proved adept at finding small steps of common ground in committee meetings and negotiations. Trygve Lie, the first Secretary General found Bunche was someone who could do the near impossible, and so assigned him to Count Folke Bernadotte, that ill-fated descendent of Napoleon’s wayward marshal, to mediate the Israel partition. The telling of this is a major part of the book, just under one hundred pages, and it proved to be Bunche blooding as an international civil servant, literally and figuratively.

For the ordini, in contrast to the cognoscenti, the Count was murdered in the street, in an open car in Jerusalem wearing a white Red Cross uniform by terrorists who wanted to disrupt all negotiations and drive the fledgling United Nations out. These terrorists — the Stern Gang — included a future prime minister of Israel.

Bunche was catapulted on the spot into the top job as the UN mediator.

There follows a story, familiar today, of intransigence and hostility from Israeli Jews and from Arabs of all stripes. He had remarkable stamina and patience, perhaps born of his own personal experience of enduring the unendurable as a black man, and he kept at it. The key point is simple.

After the murder of Bernadotte all negotiations took place on the island of Rhodes. There the Israel delegation and that of Egypt, the first of the Arab states at the table, stayed in the same hotel, ate in the same dining room, and played on the same ping-pong and billiard tables. There was much posturing, partly, mainly for domestic consumption and then painful deliberations in search of the undiscovered country of common ground. After weeks, there was an agreement for peace, and instead of returning to headquarters to take a bow, Bunche went on negotiate similar agreements with other Arab states, Trans-Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq. The first agreement made the second easier to secure, and the second made the third easier and so on.

His approach reminded me a little of MacKenzie King in his days as a mediator. He got the antagonists talking about indirect matters, the size of the table, the menu, all the trivia and as they agreed on these things he went on to other minor points….one after another building up agreement. No agreement was too small because each agreement made the next one easier.

For his labor to end the Arab-Israeli War the Nobel Peace Prize committee recognised him in 1950. He copied much of Bernadotte’s approach, but the substance was his alone. Indeed Bernadotte’s approach was partly his downfall. He was transparent and punctual. He always told everyone what he doing and when he was doing it, and stuck to a rigid timetable. His meetings and travels was published the day before and he was never late for a meeting. Bernadotte also thought the white uniform was protection enough and had no body guards. The murderers had no trouble locating him.

In the lead-up to his murder the extremists in Israel had portrayed Bernadotte as evil incarnate and an anti-semite from the cradle. Think Fox News on Hillary Clinton. The truth is that during World War II as a Swedish Red Cross official Bernadotte had risked his life and limb more than once to extricate people from the Nazis, including many Jews, some later resident in Israel, and also from the Soviets. He survived unlike his colleague and compatriot Raoul Wallenberg.

The burden of racism never ended. On the ocean liner to Oslo to receive the prize he was harangued by a woman at dinner about the inferiority of negroes, she being blind drunk and too vain to wear glasses, did not realise he was a negro, until he told her. But things only got worse.

He was targeted by the House UnAmerican Activities Committee. The ostensible cause was that he attended a meeting in 1935 where a self-proclaimed Communist had spoken. The proximate cause was that Alger Hiss had appointed him to the San Francisco delegation to set up the United Nations, and anyone Hiss touched was poisoned in a reverse King Midas.

The accusations were puffed up by the some of the in(per)formers on Roy Cohn’s payroll. Shades of Fox News. The lies were so false that they were hard to refute, but nonetheless Bunche spent two weeks on written replies to fourteen accusations, searching attics, storage trunks, carbon copies, and the like to reconstruct his activities and correspondence fifteen years earlier. The investigation lapsed, but as was the way with these witch hunts, he was never cleared, though nothing incriminating was ever found. The absence of evidence was not evidence of absence.

That he had opposed Communists in the black organisations he had participated in was proof to the conspiracy theorists that he was a secret Red Agent doing so as cover. There is no win available in this cosmology.

Accordingly, accusations against him circulated among the loony right for another generation. No doubt still do in those circles. He was successful; he was black; and he was a United Nations official. These are three things loons hate. These were his crimes. To be born. Guilty. To succeed. Guilty. To serve humanity. Guilty. Why is it that I think of Fox News.

In those days the loons did not own the Republican Party and President Eisenhower demonstrated publicly his confidence in Bunche more than once, while Harold Stassen, the eternal pretender, who had worked with him in San Francisco arranged for him to receive an honorary degree from Penn.

Bunche spoke far and wide about the United Nations, and often emphasised its importance for American negroes as an international conscience. This exposure riled up the rabid right in the States.

Dag Hammarskjōld’s had been appointed Secretary General and after a period of getting acquainted, they worked together as hand and glove, vine and fence. The rule was that no citizen of a member of the Security Council could be Secretary General, ergo Bunche was never a possibility for that job.

The peace he had brokered in the Middle East collapsed a decade later in 1956 when in one of the last spasms of empire, Britain and France invaded Egypt to seize the Suez Canal, while just by coincidence Israel attacked to secure disputed territory around the Gaza Strip, which is still disputed in 2016, sixty years later. Though Bunche tried to intervene, the toothpaste was out of the tube.

In the aftermath of Suez Bunche created the United Nations peacekeeping force. There had been UN observers before but these peace keepers were supposed to keep the antagonists apart, not just report on what happened. The practice of painting vehicles white set by Bernadotte was continued. While no international uniforms were created the blue hats were used to identify the UN troops, first war surplus USA helmet liners painted sky blue, the berets came later. That was the first demand for the supply of peace keeping troops that created the market which exists today, wherein cash strapped Third World countries sell their soldiers to the UN.

More than 3,000 UN peacekeepers from 120 countries have been killed on duty as of 2016.

More than 3,000 UN peacekeepers from 120 countries have been killed on duty as of 2016.

His home life was sacrificed to his travels and to the enormous pressures on him. Though when in New York he had something akin to a normal life for weeks at a time. He and Ruth bought a house in Queens where she lived until her death in 1988. Bunche, by the way, was a heavy smoker but drank alcohol only socially and not always then, apart from the toasts.

Then came the Congo and that just about destroyed the United Nations. When Hammarskjöld was killed, Bunche was once again catapulted into the top job on the spot. Once again in this telling, Belgium earnt the reputation as the worst of the colonisers. The Congo was the biggest in a relentless flow of crises: Yemen, Kashmir, Cyprus, Somali, Namibia, Bahrain, Biafra, Vietnam, and always the Middle East, just to cite the headlines. In addition there is a crisis a day within the United Nations itself as the Soviets undermined it, the non-aligned movement discredited it, and the United States suspected it. Back and forth goes Ralph Bunche.

There is more to his story but perhaps this is enough to whet any appetites out there.

Bunche turned the other cheek many times and he forgave but he did not forget.

Ergo when President Harry Truman offered him the number two job in the State Department, he declined because in Washington D.C. years before when his daughters’ pet dog died it could not be buried in the pet cemetery because the pet cemetery was whites only. Think about that.

When UCLA offered him an honorary doctorate to bask in the glow of his Nobel Prize, he declined it because though he was objectively (by GPA) the best student another had been made class valedictorian. To his credit this other tried to refuse the honour because he knew Bunche had the better GPA.

While on the subject of declines, he also declined Adlai Stevenson in 1951 and Jack Kennedy in 1959 who both asked him to be a foreign affairs advisor at twice the UN salary in their presidential runs. He preferred the UN and New York City. Had he accepted Kennedy, he would likely have become Secretary of State.

When time and tide permitted, he was active in the Civil Rights campaigns.

Protestor with Dr King.

Protestor with Dr King.

Another nail in coffin prepared by Hoover J. Edgar.

Brian Urquhart was a long-time British diplomat at the United Nations.

Much of the book is a record of events in which Bunche participated from which the readers learns little about the man himself. How he could summon the energy and good will to attend one crisis after another remains a mystery, because it became painfully apparent after the Congo that the United Nations could do little. Still little is better than nothing.

Reading about Bunche’s experience as a negro reminded me that once leaving the Hasting Public Library one cold day, in say 1962, I walked out the door and along the sidewalk with a library patron I had often seen there. I was in high school and he was a mature man, with a frosted lens in his eye glasses that implied the loss of an eye. He was old enough to have been in World War II. He was always clean and tidy.

We had seen each other often in the library but never spoken.

That day he did talk to me briefly. While I do recall, and I just tried to retrieve the data from memory Alpha, what precipitated his comments, but I do remember his comments, which were to the effect that every negro in Hastings received communist propaganda. It was said in such a way as to imply that they were receiving it because they were communist themselves. It left me speechless and he walked on as I turned off. That would be all six of them.

Recalling that incident now reminds me that in a way, some of what I became traces back to one of the blacks. In junior English class in high school, one of the students was Sam Mullins, who was slow on the uptake but genial, and once as we walked out of class, he asked me about my plans for going to college. I was surprised, too immature myself to have thought that far ahead at the time, and I said I probably would not go, and he scoffed and said I should. He and I were not buddies but it was one of the first times I was prompted to think about the future like that. Other prompts came later, some institutional, and some personal, but that was the first.

(The teacher was a very short woman who always told us the answer before asking the question, so anyone listening, albeit a minority, could answer. We read Stephen Crane’s ‘Red Badge of Courage’ in that class. That has stayed with me. That seemed then to be a book she placed special emphasis on.)

J. E. O. Screen. ‘Mannerheim: The Years of Preparation” (1970)

The greatest Finn, Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (1867-1951), spoke nearly no Finnish. That is just one of the paradoxes of the man and the state and nation he made.

Mannerheim’s family traced back to German Hanseatic traders who settled first in Sweden when it was a dominant power and then among the Finns where there were commercial opportunities. Mannerheim is a derivation from Mannheim, as the spell-checker keeps insisting. Mannerheim had no interest in that Teutonic past and came to view Germany as an enemy. Yet late in life he made an alliance with the devil himself in Berlin, Adolf Hitler, to save Finland from a worse fate. On that. more later.

Let’s slow down and get back to the beginning. He was one of many sons in a very well off family. His grandfather had been a Count and his father was a Baron, and Mannerheim himself was a Baron. That sounds grand but in the hierarchy of his time and place it was near the bottom of aristocracy, money or no.

As a boy he was unruly, as children may be, and loved the outdoor life, especially with horses. He was sent to military school for the discipline and Mannerheim liked the idea because of the sports and horses in the cavalry and eventually entered one.

For centuries the Finns, together with Norway and Denmark, were ruled by Sweden from distant and imperious Stockholm. This Greater Sweden eventually lost a war to Russia in 1809, and Finland was created as a dependency of Russia. In fiction it was an independent Grand Duchy, whose duke just happened to be the Czar. By that fiction local freedoms and practices continued. For example, Russia made no effort to impose military service on Finns, and permitted local militias to keep the peace. Censorship and taxation were light. The Grand Duchy of Finland served as a buffer to any future Swedish aggression, and a staging ground should Russia take the initiative.

Mannerheim’s family was Swedish, that was the maternal language, though resident among Finns for centuries when he was born. (Swedish remains an official language in Finland today.) He grew up speaking Swedish as did most of the resident aristocracy.

After several false starts, he entered military school in Russia, and there he stayed for the next thirty years. (Let that sink in. Thirty years a Russian.)

Young Mannheim, riding crop at hand.

Young Mannheim, riding crop at hand.

He made a career in the Czar’s Russian army. While many Russian officers took their place by birthright, Mannerheim worked for his, and once there, he worked at it, unlike so many others. Accordingly, he rose through the ranks. He was, remember, a Baron, and there was no social barrier to promotion.

When Nicholas II was crowned, Mannerheim was selected as one of four officers who stood an honour guard on the steps of the church, a singular honour for someone who spoke Russian poorly with a heavy Swedish accent. The one barrier he faced in the army was speaking Russian, but he worked at that with the same application he showed to much else.

He married a Russian aristocrat who soon found him boring and took herself off to the south of France with their two daughters. There was little subsequent contact. She had supposed they would live in St. Petersburg while he became a staff officer, but to be promoted he had to have field commands, in one back-water after another. This book is silent on any other sexual interests he may have had.

When Russia and Japan fought over the metal and mineral riches of Manchuria in 1904-1905 he gained combat experience. He learned there that cavalry had no chance against the machine gun, and he loved horses too much to see them slaughtered to no point. Thereafter in his mind the horse was a means of transportation, not a weapon. This was not the common reaction and made him stand apart from other officers who still favoured the cavalry charge. Nonetheless he weathered his baptism of fire and gained recognition and promotion because of his cool head and clear thinking under fire.

A contemporary cartoon on the bloody conflict, showing Russia and Japan courting Manchuria.

A contemporary cartoon on the bloody conflict, showing Russia and Japan courting Manchuria.

There are estimates of 70,000 Japanese deaths, 120,000 Russian, and 20,000 Chinese by-standers in the eighteen months of combat. Teddy Roosevelt brokered a peace treaty.

The theatre of operations.

The theatre of operations.

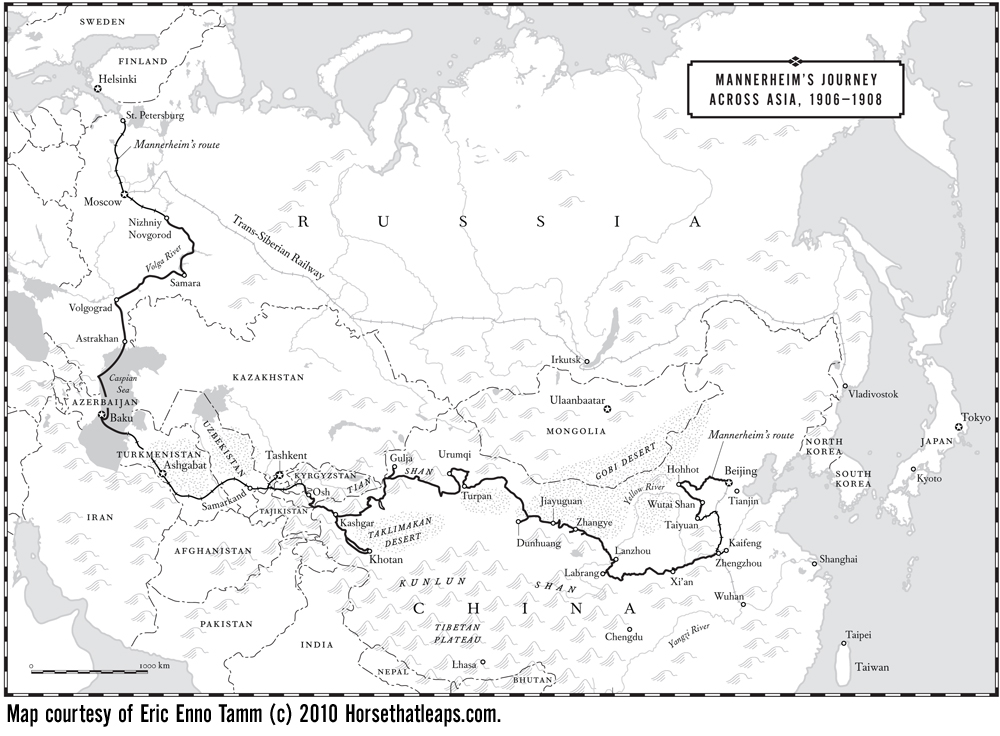

Later when the Russian General Staff wanted to gather intelligence about the far reaches of Western China, that is, Sinkiang, the duty fell to him. Mannerheim travelled for two years, filling notebooks with copious details about roads, mountain passes, fodder for animals, obstacles, fords in rivers, attitude to foreigners, capacity of the central Peking government to act in these extremities, the effect of altitude on man and beast, the grades of ascents, the frequency of avalanches, and more. He was a meticulous notetaker, a keen observer, and inquisitive questioner, so much so that Chinese authorities more than once interrogated him as a spy but his cover as a scientific explorer held. When he reached the Russian legation in Peking, it took him two months to write a report based on his notes. It was later published in two volumes.

Mannerheim’s Asia route.

Mannerheim’s Asia route.

Leaving aside the myriad of details, what is most impressive about this exercise is, first, that he did it largely unaided, and, second, that he realised the area had no strategic value and said so. At best a Russian incursion there might draw off Chinese men, material, and attention from the real prize, Manchuria. He said as much in his report.

He was offered another such mission but respectfully declined because he was anxious to return to field command to continue his way up the promotion ladder. In 1914 when the lights went out all over Europe he was a Major General in the Russian army and led troops into combat against the Austrians in Rumania and Germans later in Poland.

While he had been in the Orient, the Russian hand on Finland tightened. Taxes increased. Traditional freedoms were curtailed. Censorship increased. The imposition of the Russian language grew. Mannerheim’s correspondence with his large clan of brothers and sisters made him vaguely aware of this change. But there is no doubt he felt torn between a maternal interest in Finland and his personal oath of loyalty to the Czar.

Russia had been home to him for thirty years and had provided him with many more opportunities than Finns could have. He knew far more Russians than Finns, apart from his own family who, remember, were Swedes with little in common with the locals Finns among whom they lived. He spoke nearly no Finnish.

By early 1917 the wheels were falling off the Russian cart and he was caught up in it, like millions of others. He despised the mob he saw in the Bolsheviks, there was never a democratic sentiment in this man, and took leave to recuperate from war wounds in Finland, passing through the St. Petersburg station from which Lenin emerged.

With Russia collapsing, Finns declared themselves a country in 1917 and set about making one. While autonomy appealed broadly to Finns, there were many differences over the specifics. Some wanted to remain close to Russia for protection, while others wanted an entirely new course. On another plane were those who wanted a Bolshevik revolution in Finland to displace the established order of aristocracy and church, and others who wanted to fortify those institutions and practices against any and all threats. In time these divergent interest boiled down to conservative Whites who wanted a Finland independent and radical Reds who wanted a Soviet, which might well be aligned with Russia. (See Craig Cormack, ‘Kurrikka’s Dream’ (2000) for the Red side of this coin, with an Australian echo.)

The self-appointed Finnish Council’s first priority was to define and defend the territory of Finland, including the Karelian Isthmus, from predators, of whatever flag. Defence required an army, and army had to have a general. A few streets away sat a Lieutenant-General. This general’s exploits as soldier in Manchuria, explorer in Sinkiang, and general on the Eastern Front had been a matter of some national pride among Finns in the preceding years.

The book is very well researched and carefully argued. It begins with a survey of existing biographies of Mannerheim which is lost on this reader but affirms the care of the author in situating the work. It is based on extensive examination of Finnish, Russian, German, and Swedish sources, including Mannerheim’s own notebooks and letters. Altogether it seems to be a definitive work of the public life of Mannerheim. I could not find a picture of the author on the web.

Note, Mannerheim took it upon himself to convert the cavalry under his command to mounted infantry, and only the intervention of Czar at some point saved him from a reprimand for such an initiative. As World War I approached the Russian army was spending more on sabres for cavalry than machine guns, according to Barbara Tuchman in ‘The Guns of August’ (1962), discussed elsewhere on this blog. As journalists are always criticising the last war, so generals often prepare for it.

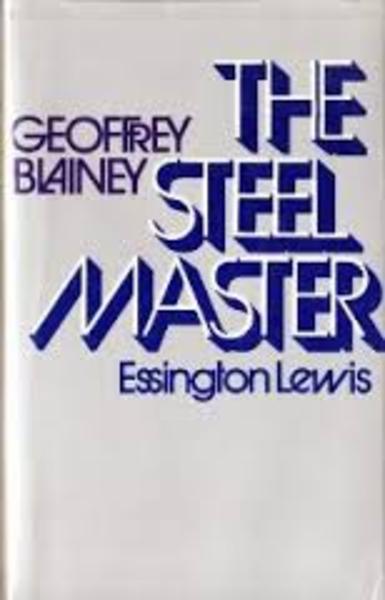

‘The Steel Master’ (1971) by Geoffrey Blainey.

Who was the Steel Master? That is today’s topic, Bleaders. Any one know? No one know?

Essington Lewis, he was the Steel Master. Huh? Never heard of him?

That is the typical response I get from the dog walkers in the park, my research sample of opportunity, as they say in the learned journals of social science. In those pages it usually means captive students in a class. My captives are tethered to pooches, mutts, and hounds.

Every Australian should know Essington Lewis (1881-1961). For extra credit Bleaders, consult Professor Google or Dr Wikipedia on the subject, and report back. Better still, consult the Australian Dictionary of Biography.

Lewis twice refused a knighthood from prime ministers Robert Menzies, Liberal, and John Curtin, Labor, because of the attendant publicity. His phasing was colourful and not suited to a family blog like this.

In time he became a member of the Order of the Companion of Honour, an award so rare few royalist have heard of it and start reaching for thistles and garters to fathom it. It is well above both undergarments and weeds.

At the time Lewis accepted it there were only five other Australian incumbents,and his adhesion was made possible by the direct intervention of King of England. C.H., as it is styled among monarchist, is a club open only to long serving prime ministers. That single criterion excluded Lewis. It is an award so discreet, it escapes, like so much else, the notice of the ever vigilant press.

He was BHP for a generation.

Essington Lewis

Essington Lewis

There was a time, and not so long ago, when every Australian knew that BHP was the Big Australian. BHP stands for Broken Hill Proprietary which began in silver and lead mining and converted itself, in good part thanks to a young Essington Lewis, from the declining silver mines of South Australia to steel manufacturings in Newcastle on the Hunter River, near all that coal for firing the smelter.

Lewis was born and bred in South Australia, educated in the Adelaide Mining School, apprenticed to a BHP property when it was one of hundreds of small mines in the northern reaches of South Australia where the sand blows from the Northern Territory and the far west of New South Wales.

His father, a stock trader, declined not once, not twice, but three times to invest in the nascent BHP enterprise, who bred in his son a vigorous outdoor life, and an outlook on life that prized the outward, the physical, the material, control, and order. Kind of a Teddy Roosevelt without the books and reading glasses. Nor does religion seem to have figured in his life.

Essington was also a demon for detail, and no demon could hide from him in the details. He copied out passages from textbooks and carried them with long into his career, as ready references. He had his clothes altered to accommodate the notebooks he carried to record, it seems, nearly everything he saw and did. He usually had at least two notebooks on his person and he cross-referenced them one to another every night. Each was filled with his minute but legible hand writing, as he recorded, measured, weighed, calculated, hefted, and walked the properties on which he worked. In later life, he also recorded the names and work of everyone he meant on his many tours.

Here is one example from this early days. At the mine the teamsters would tell him how much chaff each horse consumed a day to do its work at a mine, and Lewis would note it, and multiple the cost, but he would also rise at 4 a.m. and feed the animals himself for a week to double-check it. In so doing, without changing the diet for the horses, he hit upon a more efficient way to distribute the chaff and instituted it. This is one of hundreds of examples of his attention to detail.

His strength was in assessing and evaluating, not in innovating, inventing, or developing. He worked his way up from school-boy apprentice to become managing director of the Big Australia when he was thirty-nine, passing over at least three others, each twenty years his senior. For their parts, each accepted his elevation with good grace.

Even before sitting in the big chair, he saved BHP from a blunder. The outgoing managing director had committed to a certain type of steel operation at Newcastle and had began buying equipment for it from the England and the United States. Lewis, though he needed the good will of the outgoing managing director to be promoted as his successor, argued against this kind of operation on technical grounds, and that first slowed and then stalled the implementation of it. Lewis was right, vindicated in examples of other steel operations that had used that method with bad results. Despite this clash, because Lewis’s arguments were based on technical facts, and at no time did he engage in any personal rivalry, come the time, the outgoing managing director recommended him.

Lewis would not have hesitated one instant in opposing the boss’s decision. Technical considerations were the only considerations. He would not even have thought of keeping quiet to gain the promotion.

In person he was blunt and direct. He did not ‘suggest’ or ‘recommend,’ or ask for something ‘to be considered.’ He just said it. While on the factory floor this manner was coin, the higher he rose in the company, the politer the society with which he mixed, the more this bluntness annoyed, riled, and irritated many with who came into contact with him. He himself did not seek anyone’s society, and shrank from publicity of any kind. Unlike the Skases, Edelmans, Bonds, and Palmers of recent fame in Australian business, his picture was never to be seen in the press.

BHP went from a small hole in the ground to the Big Australia in part because of fortunate circumstances. Just as BHP was selling off its silver and lead interests to move into steel World War I led to a global demand for steel. Just as BHP was recovering from the post-war slump in steel demand, the automobile renewed the demand.

As managing director Lewis stressed education in his workforce and he sent the senior employees on study tours around the world every five years. He did so himself, as well, partly to learn the latest in steel technology but also to lure investors to Australia to consume the steel BHP made. The emphasis was always on the technical, improving what is already done. By contrast, he would not invest a single solitary shilling in research. Research to his mind, was just speculation. Let someone else pay for that.

This was an attitude about research that seeped into Australian industry, confirmed by the success of BHP. It also explains many of BHP’s subsequent misfortunes, and the like misfortunes of Australian industries in general.

Before becoming managing director, Lewis had his first trip out of South Australia to Newcastle on the Hunter River to look at the steel works site, and then around the world to examine steel production. This trip exceeds even Alexis de Tocqueville’s study tour for its depth and intensity. Lewis filled one notebook after another with observations from the cauldron of a smelter to a rolling plant to a board room across the United States and back, and then onto Europe. In time he shipped back to Melbourne, where he took up residence, several steamer trunks of notebooks, plans, technical drawings, copies of reports, extracts from assays, most in his own hand writing. The notebooks record the names of 1,700 people he met on the tour. All of his subsequent trips were like that.

He had married in his twenties and his wife and their subsequent children do not figure much in this telling. She was frail, and had a tuberculous, the disease that killed their second child. She devoted herself to good works in and around Melbourne.

Curiously, neither Federation nor World War I had much impact on Lewis. There is nary a word about the former in these pages. Nor the Boer War for that matter. Two of his brothers went into the army, and he thought about it, but was dissuaded because of the importance of the war work BHP was doing in the manufacture of ammunition. That much is said, but as seems to have been characteristic of the man, he did not think twice about it. The many hundreds of letters that remain, offer no insight into his thoughts. Invariably, the biographer has it, they describe events and actions. There are no ruminations to be found, and no confidences shared.

But World War II was his finest hour. He became director of munitions and then aviation production. By late 1944 he was managing director of three firms: defence industries employing 144,000 (many of them women), aviation production employing 50,000, and BHP itself employing 20,000. He worked eighteen hour days and took no salary, nor did any of the dozen or so BHP employees he took with him into his defence work. The Owen Gun that played so major a role on the Kokada Trail came from Lewis at the Kembla Plant. The Beaufort bombers that harried Japanese shipping in the Timor Sea came from the BHP plant at Fisherman’s Bend. When Holden could not figure out how to make tanks, Lewis took the assignment into his own hands and turned them out in anticipation of a Japanese landing.

He conducted his war work in Melbourne boardrooms where he cajoled, bribed, and bullied other industrialists to match his personal efforts and those of BHP. He also toured war industries throughout Australia on exhausting missions where he went to the factory floors to study the processes, as always looking for improvements, and talked to machine operators, storemen, women on the assembly line, and even, on one notable occasion, the janitor about what he found when sweeping out the place. In all of this he brought improvements to many facets of Australian manufacturing and business well beyond BHP.

This attention to detail is a great strength, and a great weakness.

But, I should have said earlier, he had insight into the bigger picture sometimes. On a 1936 study tour he went through Japan, where he was treated with exquisite courtesy, while being denied access to anything of substance. He wrote to a colleague that he found the courtesy aggressive and confining. When he returned, his petitioned politicians across the spectrum to prepare for war with Japan. He had concluded Japan was to be an aggressor.

Fearing to arouse Japanese attention, ‘maybe they won’t notice us if we keep our mouths shut’ was the key to Australian foreign policy, and that meant his arguments fell on deaf ears in Canberra. But he believed what he said and begin by fiat to put BHP on a war footing. He caused the Big Australian to tool up for the production of weapons, warships, and airplanes years before the war. When the war started in September 1939 BHP has an air fleet of dozen planes it had made itself which he donated to the Royal Australian Air Force.

In death his aversion to publicity continues. While the massive War Memorial (museum) in Canberra pays homage to every aspect of the home front of World War II, aboriginal patrols, land army, sock sewing, industrial production, Beauforts, Owen guns, nowhere is his name mentioned that I could find on a 2016 visit.

While the National Portrait Gallery online catalogue lists an oil portrait done of him after the war, when we visited in April 2016, it was in storage. The only surprising thing about that was that the guide we asked recognised the name, but was more interested in telling me about the painter, not the subject. Yes, I know galleries and museums have oodles of stuff they do not, cannot display. So Essington Lewis is in a warehouse in Fyshwick, and merchant princes like Jones and Coles are featured in the gallery, along with a self-portrait of man who painted Lewis. Figure out the priorities there.

Once up a time I had heard something about Essington Lewis, and so, unlike many others, I knew who he was. What I had heard was linked to a play (‘I am work’) must have had a lot of publicity because I remembered it, though I never saw it. I even wondered if it had been a radio serial on the ABC, but cannot verify that. Indeed, even tracking down the play proved to be pursuing an untamed ornithoid, as Mr. Data said in ‘The Last Outpost.’ But thanks to a friend I have now it in my Amazon basket. The irony is that the seller is in upstate New York and does not mail to Australia. Plan B it is.

This is a lobby poster.

There is no doubt that Lewis was a workaholic. He endured social occasions when he had to but never drank and seldom ate at them. He planned holidays he took like work missions, and took few of them. Idle at home, that he could not endure and went to the office, usually counting the steps as he walked. He had no outside interest and no small-talk. It was engineering or nothing.

The memory of that play left me with the ambition to read or see it, and when that failed, I looked for a biography and found this one. I hesitated for a time, in my precious way. Blainey became a pontificator in the latter 1980s for a vestigial White Australia, though no doubt he would thunder at such a crude characterisation. Indeed he did a lot of thundering into the 1990s against all the changes occurring around him. Me, I just grumble and get on with it.

Geoffrey Blainey

Geoffrey Blainey

I had no wish to dine at his intellectual table, but lacking alternatives, I overcame my churlishness. After all, it was my loss not to read the book, not his. The book is well written and impressively researched, though I found it did not have narrative drive. Reading it was uphill, but I put this down to Essington Lewis, who was a pre-eminent drone, and not to any failure on Blainey’s part. Too bad that.

‘Orde Wingate: A Man of Genius, 1903-1944’ (2014) by Trevor Royle.

File this under leadership. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk suggested this title to me and I downloaded it onto the Kindle. I had a vague recollection of the name Wingate from Burma in World War II and before that Palestine. Emphasis on the vague. There in those places he was a solider, but who he was and how he came to be there and what he did there, these were unknown to me.

The author’s many careful efforts to make Wingate likeable or admirable fail. Selfish, egotistical, opinionated, volatile, contrary, argumentative, self-absorbed, vain, destructive, delusional, contradictory, and arrogant, these things he was. Genius? Well, how would a mere mortal know?

While his family had money, most of it was given away to charities converting heathen Africans to Christianity. His parents were fervent Christians who preferred prayer to coal fires in winter, prayers to doctors, Bible reading to schools, and waited every day for the second coming of the Saviour.

Because the devil is devious, his father occasionally beat his oldest son, Orde, as a preventative measure. One of Orde’s sisters wrote an angry and bitter memoir of their childhood in which she describes wearing all the clothes there were and watching the fingers turn blue in the cold. The food, well there was some, but words failed her when she tried to describe it.

The Wingate children were kept at home mostly to prevent sinful contact with corrupt beings, that is, other children, while waiting for the second coming. It goes on like that. It is no wonder he became such a nutter. The wonder is that anyone could put up with him. Well, in fact, few did.

The one allowance his parents did make at home was servants, and Wingate led the rest of life on the assumption that there were nameless servants following behind him to clear up the messes he left. These were many. Some well beyond the pay grade of a domestic service.

His father had been in the army (while waiting for the second coming) and as the oldest son Orde followed in those footsteps.

In anticipation of the second coming, at first the young Orde did not apply himself, but in time he did so. The author is unsure what the catalyst was, except perhaps to prove himself to his father. He studied to gain entry to the artillery, and got it, largely thanks to the intercession of an uncle with influence on the General Staff. Many other intercessions followed in his career, as he lurched from one mess to another, usually of his own making.

Wingate spent an inordinate amount of time bewailing the establishment and its many failures and corruptions, all the while advancing his career through the influence of that very establishment. The author draws some veils over the trail but it is pretty clear that he made his way thanks to the string-pulling time after time.

There is no doubt that once he gained a sinecure he worked hard at it and when he concentrated he had considerable ability, but these periods of application were few and far between. The point is that others better suited and more willing to work through channels were denied the place(s) he got, while he denounced the very establishment that made him.

He had a self-destructive streak, as many young men do, and his was perhaps redoubled by that prospect of the second coming, and he blithely extended his risk-taking to the men under his command. He served in the Sudan in the 1920s, and led patrols against various tribes, whom the author invariably describes as rebels. Hmm. It is their home and the Brits were the invaders.

Orde Wingate

Orde Wingate

Further wangling by relatives got him posted to Palestine the 1930s where he became an anti-Lawrence of Arabia. Though a serving British intelligence officer, he became more Zionist than the most ardent Zionist. Another volte-face, and again the author cannot quite pin down the trigger. I suggest it was another one of his delusions of grandeur. Gideon come to liberate Zion.

He was a good intelligence officer. A quick study, he learned Arabic and then Hebrew, and set up the routine translation of Arabic and Hebrew newspapers, pamphlets, lists, and registers that served the British well in the Middle East.

He also betrayed the trust of his position by passing much of the intelligence he saw along to Zionist and Jewish interests. This is reminiscent of the flippant betrayals of Kim Philby, who never gave treason a second thought. Neither did Wingate. Neither counted the bodies because of their treason. When Wingate’s treason became known, it was hushed up on the grounds that to reveal it would be bad publicity. He prospered where another officer would have been courtmartialed and cashiered. This is a recurrent theme in his career. A giant debacle is covered up and he is promoted. Wingate learns that he can do no wrong, and continues in the same vein. (The author does not use the term ‘treason’ nor compare him to Philby. That is my work.)

He got away with behaviour that few others would do, let alone survive, and he thereafter prospered. He struck enlisted men more than once, and was not even reprimanded for it. Indeed he got away with so much that the rumour spread, and became self-fulling, that he had a powerful protector in the hierarchy. He then got away with even more childish behaviour that is all too tiresome to review. It is a reminder of the frequent inability of organisations to handle unsocialized miscreants, like the villains who embezzle millions from banks or the doctors who experiment on patients in hospitals.

His early efforts at combat were disastrous for those under his command. Though the author skirts around it, this reader concluded that Wingate had no grasp of small arms tactics and managed to get his men into a cross-fire of his own making. Rather than be reprimanded, he got a medal for that action, and four dead. That’s the pattern.

He did learn from the cross-fire, and later stressed infantry tactics, something the author seems to think is a sign of his genius. After leading his men into a self-made trap, he then read the field manual. Genius that.

Again despite the author’s delicacy, it is also pretty clear that Wingate’s raids on ‘Arab rebels and gangs,’ as the text styles them involved murdering women and child, preferably in their sleep. These crimes the author puts down to his enthusiasm. ‘Crimes’ is my word, not the author’s.

His personal life was as chaotic, reckless, and destructive as his professional life. He wooed a young woman who waited patiently for him for six years (biological clock ticking) while he was promoted in the Sudan, and then he jilted her without a backward glance.

He threw her over because at thirty-one he had fallen in love with a fourteen year old girl. You read that right. I skipped through a lot of this quickly and I may have the ages slightly wrong but he was twice her age and she was underage. More waiting, and eventual marriage.

Throughout these campaigns he carried a Bible at all times and often referred to himself as Gideon. He meant that literally.

During World War II in Somaliland and Ethiopia against the Italians and Burma against the Japanese it was more of the same on an ever larger scale. By the time of his death he was a major-general, hard though that is to believe. In Burma he concocted wild schemes that got a lot of men killed to little strategic purpose, as far as I could see, despite the author’s efforts to dress it all up. On this point more below.