This novel is derived from the the life of Job Harriman (1861-1925) an American socialist leader. He was Eugene V. Debs’s running mate in the 1900 presidential election. He also contested the mayoralty elections in Los Angeles twice prior to the Great War.

1911 campaign button

1911 campaign button

Though afflicted by tuberculous he campaigned with a fierce determination. Giving up on politics later, he led a band of true believers into the Mojave Desert east of Los Angeles to carve out a city on the hill at Llano. That effort failed and a splitter group followed this Messiah to the wilderness of Louisiana to New Llano in the pine forests on the Texas border.

The Los Angeles elections were brutal, marked by street fighting and bombs. Harriman was born to the priesthood, and campaigning gave him a chance to preach which he did with vigour and vehemence. Those who were trying to establish labor unions saw socialist politics as a distraction or worse. Then there were the Wobblies who had no use for union incrementalism or socialist election campaigns. All three of these elements were well represented in Los Angeles before World War I. Ranged against them were the plutocrats and robber merchants of the era along with the railroad magnets, who were the worst of a bad lot. In between these zealots, as always were the decent majority.

In the novel Harriman (in these pages styled Bannerman, for some reason) campaigns diligently for the Debs ticket in 1900. ‘Based on a true story,’ as they say in Hollywood, because Harriman did not campaign at all. Harriman could barely abide being in the same room with Debs (who was a union man first and last) and Harriman went to a conference in Europe to talk about socialism during the entire campaign. Because of his origins and commitment to labor unions, the hope was that Debs would unite the factions but he was reviled by the holier-than-thou socialists like Harriman and despised by the Wobbles. Harriman was on the ticket not to help Debs campaign but to hold a place for a real socialist.

The ‘dynamite’ in the title has two meanings. The first is Harriman at the pulpit; he was a dynamite speaker. The second, literal meaning, refers to the bombing of the Los Angeles Times building in 1910. The owners blamed the socialists, labor unions, and Wobblies without bothering with the minute distinctions among them that so pre-occupied them. The socialists and labor unionists said that the owners had blown it up to put the blame on them. The Wobblies wished they had bombed it. If all this starts to sound like the Reichstag fire in 1933, there are parallels. No doubt some among the plutocrats would have been capable of such a deed, but they did not have to do it.

Clarence Darrow led the defence for the two brothers accused of the bombing, and Harriman worked with him. But the bombers confessed, having killed twenty-one (21) workers and injuring a hundred more, it hardly seemed a blow for the cause. The novel slides over the top of these facts, as it does many others. Bannerman-Harriman convinces himself, perhaps thanks to a feverish dream caused by his tuberculous, that the bombing and subsequent trial represented some kind of victory for socialism.

The move to Llano proved difficult in every respect.

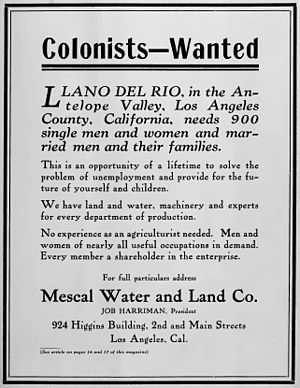

Recruiting advertisement

Recruiting advertisement

The one thing that money cannot buy in Southern California is…water. The Mojave desert, home to Joshua trees, is called a ‘desert’ for a very good reason.

Joshua Tree

Joshua Tree

Llano was on the edge of the Mojave and water was scarce. The United States Weather Service says the average daily temperature at Llano ranges from 37C to 41C over a year. Whew! Booming Los Angeles soaked up all the water there was. See ‘Chinatown’ (1974) for a reminder. Long after Harriman and his band of believers left the area, Aldous Huxley spent some time nearby using peyote and, he said, starting to write ‘Brave New World’ in that drug-induced state.

Ruins at Llano.

Ruins at Llano.

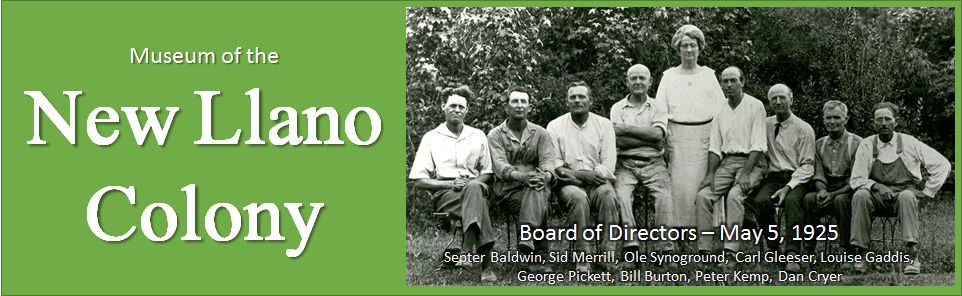

A hard core followed the prophet Harriman to the pine forests of northwest Louisiana near Leesville and founded New Llano which eked out an existence for a few more years in a sawmill operation. It demonstrated admirable pragmatism in finding means to sustain itself, unlike many other intentional communities. The economic boom of World War I made the mill profitable, while those in New Llano denounced the war as a plutocrats’ war and avoided the draft with ingenuity. In both Llano and New Llano Harriman was something of a tyrant imposing his will on one and all, when he had the strength to do so, but that is omitted from this story. One of the reason Llano fractured was because, as one participant said, they had but exchanged one boss for another. By the way, Job Harriman was no relation to Averell Harriman (1891-1986) of New York.

From Museum of West Louisiana

From Museum of West Louisiana

The Los Angeles Times had sworn a vendetta against Harriman, it seems, and it maintained the rage with repeated press attacks on him while he was in Llano, and even when he moved to Louisiana it did not relent. The attacks were as creative and truthful as Fox News. The Llano colony lasted three years and New Llano another seven years. In the annals of such intentional communities ten years is a good run.

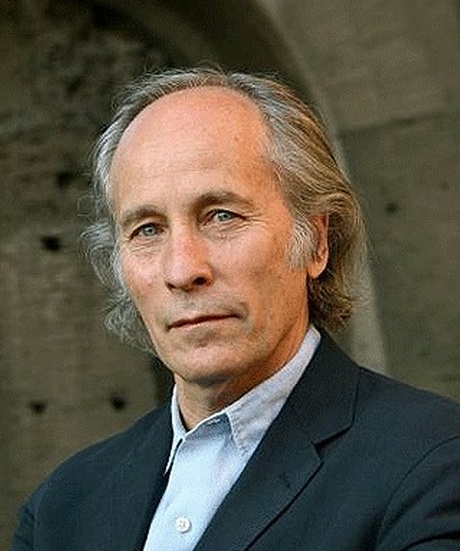

Robert Hine

Robert Hine

California historian Robert Hine turned his hand to novels, this being the second. It is all rather didactic and the characters are all surface.

Category: Theory

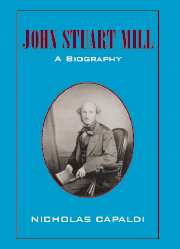

‘John Stuart Mill: A Biography’ by Nicholas Capaldi (2004)

This book is an intellectual biography of that singular individual John Stuart Mill, son of James Mill and husband of Harriet Taylor, these two being the most important facts in his life. Hereinafter James Mill will be referred to as James Mill and John Stuart Mill as Mill. Got it?

James Mill’s father, Mill’s grandfather, was a shoemaker in Scotland. James Mill was a bright lad and earned scholarship to finish a basic education and became ever after an autodidactic. The family was and remained irreligious and that barred James Mill and Mill from the clergy, the most learned of professions, as well as from the law and parliament, and also universities. A lawyer, a parliamentarian, and a university don, each had to accept publicly the thirty-nine orders of the Anglican Church and neither James Mill nor, later, Mill would do so in contravention of their own beliefs. For someone with intellectual interest and ambitions there was little other opportunity, but to work as a clerk. Since Ebenezer Scrooge was not hiring, James Mill found his way to the East India Company, which was a private corporation and did not require allegiance to the established Church.

James Mill

James Mill

James Mill was a hyper-Calvinist in everything but theology. He was exacting and critical. He prospered at work, and educated all of nine children at home. His education of Mill at home is well known. It started at about age 3 by which time young Mill was reading Plato’s dialogues. It was a massive and unremitting program of force-feeding. Mill in turn was made to teach his siblings. The children seldom left the house and none had any friends. Mill does not mention his mother even once in his ‘Autobiography’ and James Mill treated her like a servant, said those who visited the house.

Mill was a child prodigy and completely inept social and physically. He had no friends and never played any games that boys played and so his motor skills were limited to shoe tying. The same is true of the other children but Mill is the focus here.

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill

James Mill was an acolyte of Jeremy Bentham and together they sired utilitarianism as a social and moral school of thought. Bentham became a de facto godfather to Mill who in turn was the godfather of Bertrand Russell. Bentham discretely supported James Mill’s family, having made a pile of money by investing in a mill in Scotland. The milll was at New Lanark and run by Robert Owen, himself a social reformer of note.

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham

Bentham had a joie de vivre that James Mill lacked and Bentham in time revealed to young Mill something of the wider world of poetry, drama, literature, and walks in nature, and a visit to France which made the young Mill a Francophile. James Mill deferred to Bentham’s influence on his son, Mill, but turned each new interest into another assignment. A walk became an exercise in collecting, identifying, researching, and preserving botany samples. The visit to France with Bentham required Mill to learn French. To read Shakespeare became and exercise in the history of the English monarchy. James Mill drew a line at Shakespeare’s history plays. These Mill could read but not the tragedies or comedies. They might be a bad influence. See Plato on the dangers of poetry. James Mill made Mr. Gradgrind look like light relief. See Charles Dickens’s ‘Hard Times.’

I have long thought that Mill had the education of a Platonic philosopher-king. At first he learned by rote and repetition, seldom understanding what he read. His father was impossible to please and the slightest hesitation, not to say error, would mean the whole lesson had to be repeated from the beginning. Mill feared his father’s judgement. (Yes, James Mill was feared rather than loved but not hated.) One lifelong friend of James Mill said that he, James Mill, never praised anyone and criticised everyone immediately and often. When Mill taught his younger siblings, if one of them made a mistake, James Mill required Mill to repeated the lesson until all eight children were letter perfect. Their home schooling started each of seven days at 5 am and continued to 9 pm. James Mill conducted the hours 5am to 9 am and then went to work at the India House, returning for the testing session from 6pm-9pm. From 9 am to 6 pm Mill schooled his siblings. Such reinforcement as James Mill offered was always negative, though never corporeal.

James Mill educated his children at home because school education was too shallow and sloppy. His children seldom left the house. Likewise he saw no need for any of his children to go to a university. He particularly concentrated on Mill to make him the perfect and complete exposition of utilitarianism. James Mill created Mill so that he could go forth and reform the world in the image of Jeremy Bentham. Mill was an android artificially made for a mission. Indeed some of Mill’s peers in later life referred to him as the mechanical man. Mill’s upbringing differed from Plato’s philosopher-kings who were reared with others destined to be guardians and auxiliaries and even when crowned they did have annual sexual relations and common families, but Mill did not have any of that. They had social and sex lives, albeit constrained, that he did not have. A single purpose android is a more accurate description, like Mr Data without the tap dancing.

The software in the android became corrupted and Mill had a nervous breakdown when he was twenty (20). In his ‘Autobiography’ Mill blames this breakdown on the strain of his intellectual work. Capaldi, like just about everyone else, sees in it a suppressed rebellion against his domineering father. Mill did gradually recover his health and continued publicly to support his father in every way, but he began at this time to think for himself and gradually to step out of his father’s shadow in the safety of his own mind. After his father’s death Mill began to change utilitarianism, adopt liberalism, court Harriet, and more.

Harriet Taylor

Harriet Taylor

Mill’s long courtship of Harriet is well known. It was contentious and scandalous at the time. She was a married woman, and yet they were seen everywhere together, she clinging to his arm and he deferring to her, including at least one unchaperoned trip to France. Mr. Taylor was none too pleased about any of this. Given Mill’s repressed nature it is unlikely that Mill and Harriet had sexual relations, but by the standards of the day, that hardly mattered. He thought the world of her and extolled her qualities far beyond the mere mortal. When Taylor died that freed Harriet, divorce having been out of the question, the appearance of adultery was preferable, it seems.

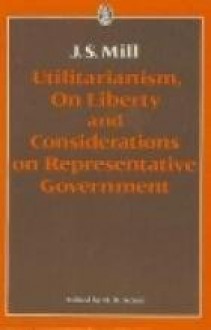

They married almost immediately after Taylor’s death and had about ten years before she died. I had not realised it, but the three most famous of his works came after her death: ‘Utilitarianism,’ ‘On Liberty,’ and ‘Considerations on Representative Government.’ Mill thought of these essays as memorials to her. In all of these three, along with his earlier work, the underlying and unifying theme is autonomy, defined as the capacity, the ability, and the responsibility to decide for oneself. Achieving that was a moral goal for individuals and a determinant for public policy to create the conditions for individuals to develop the ability and capacity for autonomy through education, example, discipline, exposure, personal growth, and surrender to the larger whole. Insofar as democratic political institution encouraged and promoted autonomy he supported them though he had learned from Tocqueville to fear the tyranny of the majority (for a current example, watch 7MATE for one whole day).

Autonomy is not license or freedom, nor even liberty. Think of an orchestra. Now take away the conductor, the first violin and any other authority or leader. If the musicians are autonomous their own comprehension of the the needs of a given piece of music will lead them to participate, or sit it out, and to do it a certain way that blends them together into a whole. a if they had a conductor. If and when that happens, that is autonomy. By the way, there are leaderless orchestras that do not descend into the conflagration of the Fellini’s ‘Orchestra Rehearsal’ (1978). Another example that came to mind is the Gospel of Mathew that calls upon believers to decide for themselves, and in so doing their decision will coincide with the divine. Emmanuel Kant makes a powerful example from that gospel by urging the devout believer even to turn away from a risen Christ, and decide… In the telling most of the power is lost; read it in Kant.

He also served one term in parliament where he was a formidable committee man, I believe, but none of his committee work is mentioned in these pages. I have read Hansard micro-cards that record of some of his testimony to parliamentary committees and interventions while on committees and found them to be trenchant. What I saw related to the Northcote and Trevelyan reforms of the civil service. In his parliamentary career Mill was usually on the side of the angels but not always. He argued and voted for the death penalty for murders.

Capaldi does a superb job analysing Mill’s many, many texts and shows Mill to be a far more complex thinker than revealed by the simple elegance of his own prose. Capaldi brings out well the the French and German influences on Mill. For the French there is Tocqueville, of course, but also Saint-Simon fils and Auguste Comte. For the Germans the romantic poets and even that dynamic duo of Kant and Hegel. In all, Capaldi goes a long way to establishing Mill as a figure who cannot be typecast. Was he a conservative? a liberal? a radical? a democrat? an elitist? a deontologist? a utilitarian? a positivist? an empiricist? The answer in each case is ‘yes’ but in his own special way. He was both a liberal and a conservative.

Mill had form. He was arrested for obscenity while a teenager. The crime, of which he was certainly guilty, was passing out pamphlets urging birth control.

Mill was a lifelong proponent of female suffrage. When he and Harriet married, they went to some pains to avoid the norm according to which he would have become the owner of all of her goods, including a considerable inheritance from Taylor.

Mill’s book ‘A System of Logic’ made his name in the first instance. It was so highly regarded that in addition to large sales, almost immediately, it also went on the curriculum at Oxford and Cambridge. In short order, his other books began to follow on to the curriculum, including ‘On Liberty’ and ‘Representative Government’ and they in turn could be best understand by reference to the previous thinkers he analysed and synthesised and so was born ‘Political Theory’ as a field of study in universities. Indeed his impact on the Oxbridge universities, where he never set foot, was so great that after his death, academic reputations were made by tarnishing his; the attack of the pygmies on the defenceless is always a sure sign of stature.

Because of the range of Mill’s works, after his death he was claimed as a precursor by a wide variety of causes from co-operatives, Fabian socialism, and the 800 Club. To his contemporaries Mill was an enigma: he did not fit into any of the categories available, and they knew it. It is still true that he is an odd man out but we generally no longer recognise that, and force him into one box or another, and then dismiss him. Our loss. Today he has largely been reduced to a stereotype no less distorted than that which applies to Machiavelli.

I would have liked a more clearly presented chronology, maybe as an appendix. I also found it hard to read, especially the extensive quotations from secondary sources and Mill’s own ‘Autobiography’ which interrupted any flow the text had. While the early chapters fill out Mill’s life well, that falls away in favour of ever finer-grained examination of his ideas, arguments, and publications, despite the subtitle: ‘A biography.’ I found almost nothing about his forty (40) years of work for the East India Company, though the author does suggest that his responsibilities were comparable to a cabinet minister. I stress this reference to India because the last pages of ‘Considerations on Representative Government’ say somethings about India that give one pause. Indeed the last lines refer to India as ‘semi-barbarous.’ His tenure with the East India Company included the Sepoy Rebellion, so it was not all business as usual.

Nicholas Capaldi

Nicholas Capaldi

The wheel turns. James Mill and Mill did much to govern India from London and today India does the same for Britain through those call centres. In fact, there is so much demand for Indian call centres, I discovered, that Indian companies are sub-contracting many of them to the Philippines. I am pretty sure that recently when I called AusGrid to report a burned out street light outside our front door, the agent I spoke to was probably in India, the accent, the slight lag in voice transmission, the formality of word choice…maybe.

Mark Adams, ‘Meet me in Atlantis: My Obsessive Quest to Find the Sunken City’ (2015)

‘Obsessive?’ ‘Obsessive!’ Yes, indeedy.

From little asides big myths grow. The sum total of human knowledge of Atlantis comes from a couple of pages in two of Plato’s dialogues, the ‘Timaeus’ and the Critias.’ These two are not in the first rank of Platonic dialogues. A great many admirers and readers of Plato have never heard of them.

The ‘Timaeus’ is a conversation set the day after the conclusion of the discussion of the ‘Republic.’ (Since there is no republic in it, for millenia pedants always wonder about that title. Answer: It was bestowed on the work by Cicero hundreds of years after Plato’s death. Cicero was not much interested in accuracy, think of him as a Fox journalist. No doubt it suited his purpose to have Plato legitimate a republic on the assumption that no one else would read the whole book.)

In turn, the ‘Critias’ continues the ‘Timaeus.’ In the few lines that mention Atlantis it is at a great remove from Plato. It is allegedly a story that an Egyptian told Solon hundreds of years earlier that is reported by one of the interlocutors. It mixes very specific details like the colour of building blocks, and the measurements of temple while being maddeningly vague about where the place was except for a reference that has been translated as ‘beyond the pillars of Hercules.’

What with all his labours, Hercules seems to gotten around the Mediterranean. Atlantologists have located the pillars at Gibraltar, Malta, Messina, Crete, Santorini, Morocco, the Crimea, and, believe it or not, Ireland. Yes, Ripley this really is ‘Believe it or not’ country.

Our cicerone is not quite right in that subtitle above. The book is not about his quest so much as that the other Atlantogolists he seeks and meets. Some he sought out in libraries and archives, and others on the internet, and he went to meet many of them in person. The book is a travelogue about the Atlantologists from Ireland, Germany, Morocco, Sicily, Greece, Malta, United States, Great Britain, and more. He had some travel budget did Mark.

The one place bruited as Atlantis that he did not visit was…. Antartica. Yes, Antartica has been identified by some as Atlantis, which drifted south after a cataclysm.

The tone is light and the prose snappy. While he is not a true believer in the Big ‘A,’ there are no cheap shots at those who do believe in Atlantis. This is no Bill Bryson hatchet job passed off as humour.

He does call the many interpretations of Atlantis ‘theories’ and that annoyed me because they are speculations, not theories. A theory joins evidence and analysis. Speculation is guess work without either.

The many ways in which Plato’s few lines are interpreted include, deciding that he meant 900 and not 9000, and the latter is a transcription error made by a scribe in ancient Egypt. Well, yes, it could be, and that scribe might have had red hair but however are we to know?

As for the ‘pillars of Hercules,’ every part of that is deconstructed and reconstructed to suit the desires of the speaker. ‘Pillars’ can refer to many things, far more than I ever thought. And Hercules, well he was several other chaps with the same name all over the place like John Smith. On it goes. The Wikipedia entry is a site of constant conflict. It changes every day as the Atlantologists slug it out on their keyboards.

When I first read the ‘Timaeus’ I thought the reference to Atlantis there was an undeveloped allegory on the hubris of peoples, not a road map. I took it to be a parallel of the Allegory of the Cave, and no one has yet set out to find that very CAVE. Silly me, once again I missed the point.

Some of the Atlantologists he met are safe, safe, and sober who discount the wild speculations of the many more zealous of their number, but find the subject fascinating. One of these triple esses (safe, sane, and sober) runs a web site: atlantipedia.ie.

Others are obsessive, no doubt about it. Any claim Mark Adams has to be being obsessive is bleached out by some of the characters he met. Among them are those that cannot make eye contact, talk in 45 minutes monologues and then lapse into catatonic states, talk to him through doors for security reasons (someone might steal my Atlantis map if I let anyone in). These are not in the safe, sane, an sober zone of inquiry.

Some promote a location, like Sicily, Santorini, or Malta, as Atlantis for purely venal reasons: it brings a few tourists (even if they are nut-cases, they pay hotel bills).

One of many maps on the internet.

One of many maps on the internet.

Mixed in among these types are a collection of serious archeologists who are studying ancient ruins here and there and whose work, an Atlantologist thinks, has something to do with Atlantis. Huh? Well, goes the interpretation, these archeologists keep secret their interest in Atlantis, (a) because of the conspiracy of the rose (on this, see below) or (b) their funding would be cut if they admitted it. Maybe this is the paranoid side of the coin. Or (c) they foolishly do not realise the connection to Atlantis.

One of many representations of a building on Atlantis.

One of many representations of a building on Atlantis.

Francis Bacon (1561–1626) called his little book in praise of science ‘The New Atlantis’ and in it speculated on what science could do to conquer nature and improve humankind. Because of the great powers of science for ill as well as good, Bacon imagined its use confined to a sect who worked with this secret knowledge for the good of all on an island. (Yes, this is the same Bacon who wrote the complete work of Shakespeare according to some….)

Francis Bacon (I have seen this image passed off as Machiavelli more than once, believe it or not, Ripley.)

Francis Bacon (I have seen this image passed off as Machiavelli more than once, believe it or not, Ripley.)

Fatherhood followed. He sired, as so many have claimed, without knowing it, Rosicrucianism. This doctrine has followers today at your nearest public library, though they will not wear a rose on the lapel.

The rose cross,

The rose cross,

Start checking out, reading, asking about books on Francis Bacon and the Followers of the Rose will ever so subtly make themselves known. They live and breathe conspiracy, arcane knowledge, numerology, and a lot else not to be found on the curriculum at a university. (Not yet, anyway. I omit Pepperdine, where shoe tying is an advanced course.)

Where else? California near San José.

Where else? California near San José.

It is proof positive that Atlantis existed to the Rosicrucians that NASA named a space shuttle Atlantis. That was, they say, a coded message not only to Earthlings, but to aliens, as well. Gulp! Yes, there is an Erich van Donkey element to all this. The spell-checker changed the egregious Swiss hotelier’s name to Donkey and I decided to accept it as fitting.

Adams meets a few of the adherents of the rose along the way, nods a lot in agreement with them, hides in the bathroom to avoid others, and leaves town as soon as possible when he encounters a coven of them. Reading of his experiences made me wonder the Rosicrucians had never figured in ‘Midsomer Murders.’

Jules Verne, Walt Disney, Star Gate, an eponymous television series in 2013, and scores of others have made use of the name recognition of Atlantis, and in so doing have scattered its seed further, and by repetition perhaps planted it deeper. A google search returns a gazillion hits or 110,000,000 without even working up a sweat.

Mark Adams

Mark Adams

Having made light of it all above, I must conclude by saying that Adams does shift the evidence and evaluate the arguments he heard, without denigrating anyone, and concludes, with a phalanx of qualifications, that the ancient city of Tartessos near Cadiz in Spain is the best candidate. That is, if there ever was an Atlantis. This city has a genealogy as Tartessos but perhaps Atlantis previously occupied the site before it was obliterated in a tsunami. As to the details Plato gives of colours and dimensions, these might simply be artistic touches of verisimilitude that can be dismissed. Hey, presto! We have arrived at Atlantis!

Thus inspired I re-read the ‘Timaeus’ and the ‘Critias’ to see for myself where the fire started. The reference to Atlantis is brief in the former and continued in some tantalising detail in the latter. In the ‘Timaeus.’ An Egyptian priest told Solon, who upon his return to Greece told Dropicles, who told Critias’s grandfather who told his grandson also named Critias. These four tellings span the two hundred years from Solon to Plato. That make me think of those ‘pass it on’ exercises in school. The teacher whispers in the ear of the first child ‘The sky is blue,’ now tell your neighbour and by the time it went around the class, the ceiling was falling. The morale of the story in that case was do not believe everything said.

The ‘Critias’ has all those details that have set Atlantological hearts a-pounding. Distance, dimensions, durations, depths, and more, all of which are well canvassed by Adams.

Reading it now the point of the story seems to me to this: As big and powerful and grand as Atlantis was, our noble ancestors, the Athenians, defeated them. Atlantis had all the wealth and power but this pre-historic Athens had all the virtue: they held all things in common, the warriors lived apart as warriors, features in the fictional city of the ‘Republic’ now given an Athenian pedigree and a track record of success. And why does not the Greek in the street know this already, why because a flood swept away Atlantis and most of Greece, too, so angry was Poseidon at the hubris of the Atlanteans. This devastating flood killed all the literate men who might have remembered or recorded the story, sparing only a few rude and crude mountain men from whose loins Athens was eventually re-populated. This flood stripped Attica of its topsoil and carved the Athenian acropolis out. End of story.

Get it? Atlantis was big and powerful but no match for a virtuous Athens. Athens was virtuous because no one there cared about gold, jewels, luxuries that the Atlanteans had in plenty.

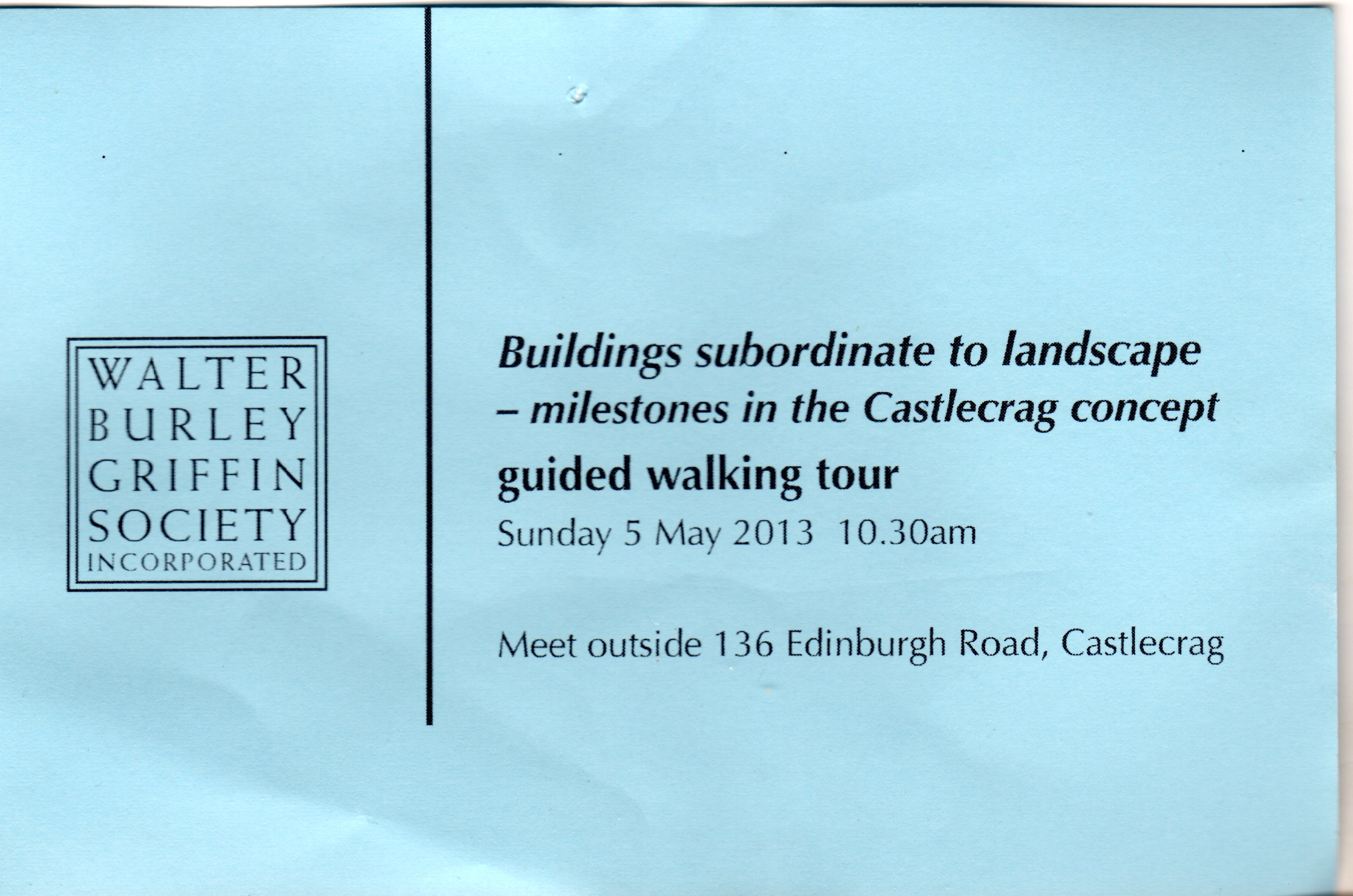

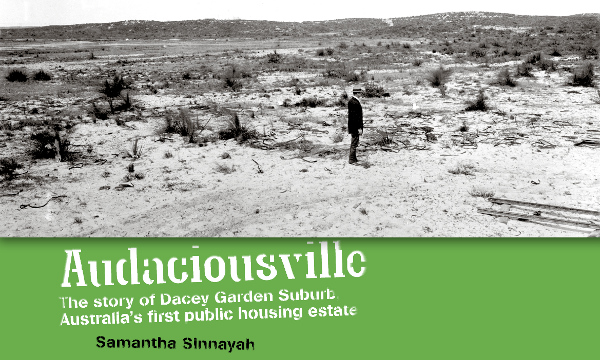

The return to Castlecrag

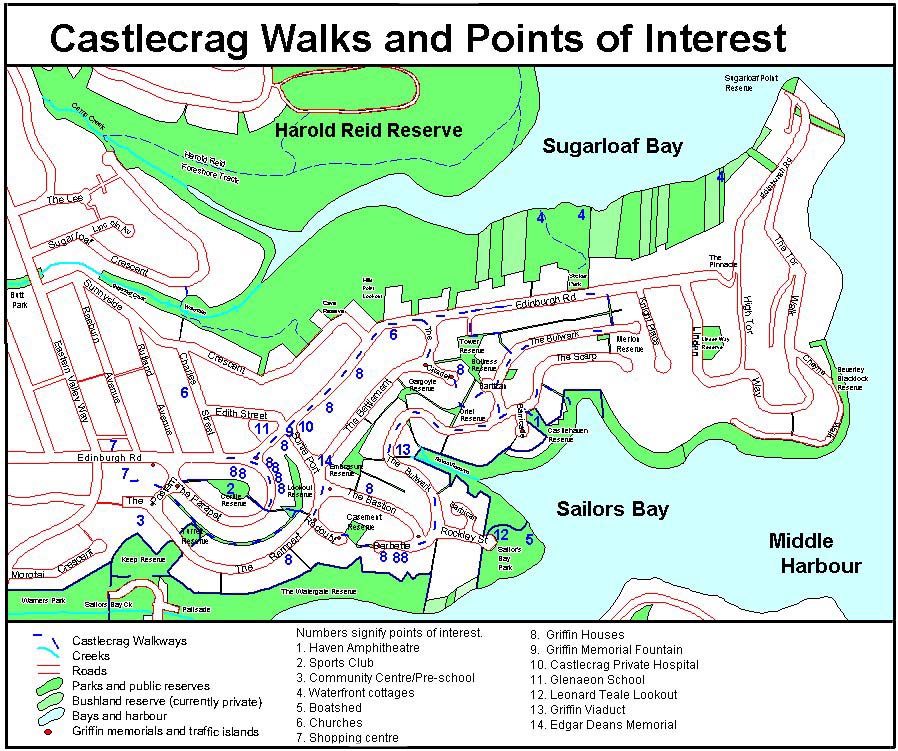

We went on a guided tour of Castlecrag over two and a half hours. Recommended to those with an interest in social history.

The walk was informative and interesting. It focussed on Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony, and also those whom they influenced in the continued development of Castle Crag, as it was spelt in those days. We walked there once on a rainy day and saw some of the streetscapes and houses, thanks to the web site of the Walter Burley Griffith Society. http://www.griffinsociety.org/index.html

That gave us a familiarity, but this walk was more detailed. It filled in many details and emphasized the community-building parts of the plan. We had the choice of an arduous clamor down to the water and back or a more gentile walk, which we choose. It was the right choice for my knees though I did (barely) mange to ascend and descend Edinburgh Rock. It was a fine and crisp autumnal day and the guide was knowledgeable and informative.

The common areas reminded me a little of the playgrounds and common areas in the Daceyville. Though Daceyville was earlier and a creation of official state planning which began in 1912 and was converted into a project for returned soldiers after The Great War. It was the product of the scourge of creative types who peopled Castle Crag, it seems from the repeated and caustic way they are mentioned, bureaucrats. It did not subordinate buildings to the salt bush plain.

In contrast to Castle Crag, Daceyville was working class. The houses are conventional both within and without. But rather than rows of terrace houses they were spaced around rings with inner play grounds and parks. It was for dinky-die Australians who still felt themselves to be British. Indeed the overall look of Daceyville is English.

For more see Audaciousville

http://swft.cobb.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/cobb/search/asset/164268?rm=DOCUMENT+ARCHI0%7C%7C%7C1%7C%7C%7C2%7C%7C%7Ctrue

Thanks to tax dollars, a free download.

In contrast, we we were reminded on our walk, Castle Crag, planned and partly built by two ex-patriot Americans attracted Chinese and European investors and residents. The Chinese came from Melbourne, while the Europeans fled Naziism. Its early residents, which were too few to make the project financially viable, were often self-styled Bohemians: artists, poets, and other dreamers, who also could never pay top pound for the Griffin-Mahony creations.

I heard it said that aboriginals were leaving on the point at Castle Crag when Griffin and Mahony came but there is nothing about that in the material.

Both Daceyville and Castle Crag seem to follow a line from the Garden City movement in England which was in turn was informed by William Morris’s News from Nowhere. For Griffith and Mahoney that line ran through Frank Lloyd Wright. For Daceyville it was directly inspired by Ebenezer Howard’s Letchworth, the first of the Garden Cities in England just outside London. When Howard failed to make a living in Lincoln Nebraska, Howard returned to England and in time he turned to town planning.

Aside, we have seen many references to the fact that in latter in life, after Walter had died, Mahony went back over some of the drawings done in his name and blacked it out. She never explained, so the slather (what is a slather?) is open. The feminists declare that she was reclaiming her own work that the dastardly Griffin had appropriated. The grey Marxists claim she was reclaiming her own work that the evils of capitalism had forced her to disown, and so on. The ideologues always find what they want to find. As predictable as a late bus.

How about this: she was mad at him for dying and leaving her alone. Everything we know, everything the above interpreters reluctantly admit, is that the two were nearly one in everything they did, though not given to spouting off about it. Then he went and died and left her alone, half. No wonder she was angry, which psychology bores will tell us is part of grief. No ideological mileage in that but maybe some truth, something that seldom interests either ideologues or journalists.

A Self-guided tour of Castlecrag

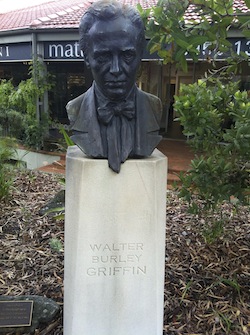

One of the items on my list of things to do for many years has been to visit Castlecrag, residential area of Sydney in the leafy North Shore (a term that means a lot here and nothing anywhere else). What is the allure of Castlecrag? The original subdivision was planned and some of the houses designed built by Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony. After they completed with their commission in designing and starting the lay out of Canberra, they spent time in both Melbourne and Sydney to practice their profession: architecture.

In Sydney they were commissioned to develop Castlecrag. The local historical association provides a map for the Griffith-Mahony work;

http://www.castlecrag.org.au/history/history.htm

I could not find a copy of Wanda Spathopoulos, The Crag – Castlecrag 1924-1936. Blackheath: Schlesigner, 2007.

William Morris in his novel News from Nowhere (1890) called for a reintegration of man with nature as the Industrial Revolution hummed along. For this work he has been accorded a place in the pantheon of Utopian thinkers. I have included it on syllabi more than once. Morris had some faint influence on Frank Lloyd Wright, if anyone can be said to have influenced that man of granite, and Wright was the mentor of Griffin and Mahony. The line of influence most probably ran through the Garden City movement of Ebenezer Howard, see his Garden Cities of Tomorrow.

News from Nowhere was serialized first and over time Morris re-worked before it finally appeared as a book. It was in good part a reaction to the mechanistic and materialistic image of the future offered by Edward Bellamy in Looking Backward (1887). Howard was aware of Morris’s book and published his own first edition shortly after News from Nowhere.

Moreover, the idea of a planned city build on a greenfield is a motif in utopian thinking about the New Jerusalem with a clean start, i.e., Canberra in this case.

So we decided to do it one rainy Friday. The rain was persistent but light and we have long since decided not to let the elements dictate to us in any but the more exceptional cases.

We saw an image of Griffin but not Mahony

We saw a number of unmistakeable houses integrated into the escarpment. Often overlooked by McMansions of more recent vintage.

Footnote on William Morris. I tried to read a biography of him but gave up reading the record of his endless petulant tantrums — precious, indeed! For a Green avant le mot he did good business. His designs founded the Morris Company which operated from 1875-1940 as Morris & Co. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morris_%26_Co.

One of the most loyal customers of Morris & Co. was the Carrick Family of South Australia. With the result that the South Australia Art Gallery and Museum have many items form Morris & Co., including some clothing. In addition, Carrick Hill offers many more Morris & Co. items in situ. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carrick_Hill

When in Adelaide it is well worth a visit.

Richard Ford, novelist, Sydney Writers’ Festival

Thanks to the suggestion of a friend I went to Richard Ford’s session at the Sydney Writers’ Festival. I have read two of his novels: Independence Day and The Sportswriter. I found them easy to read but, for some reason, I was not engaged enough to want to read more. Indeed there was a ten year gap between reading these two.

http://www.swf.org.au/

However I found Ford an engaging character on the stage, and I liked his literal-mindedness: What I mean is what I say; What I say [write] is what I mean. Do not go looking for symbols or signs. Wonderful.

Likewise the host did a fine job in bringing out what Ford had to say, and the talking heads were punctuated with Ford doing some short readings from his most recent novel Canada.

Ford said in passing early in the discussion that, literal though he was, he did write with a ‘higher purpose’ and I was glad that the first question from the floor took him back to that passing aside. He explained that this higher purpose was to renew in the reader emotions and thoughts of the complete person. I have not got his words quite right, for I was not taking notes, but that is the gist. I found that explanation to be both simple and compelling. But imagine what the Derridaistas would make of that. The heavy artillery of cant and ideology, disguised as scholarship, would rumble.

Having never attended a Sydney Writers’ Festival event before I enjoyed it and just might do it again. The only false note came from the host who made a gratuitous and deprecating reference to Des Moines, Iowa. I know people make these kinds of quips without thinking, and indeed that is the point and the problem. It betrays an enduring mindset.

Here is the web description of Ford’s talk:

Richard Ford: – 15 July, City Recital Hall

One of the masters of American fiction, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Richard Ford comes to Sydney for an exclusive event presented by Sydney Writers’ Festival. Ford visits Australia on the heels of the publication of Canada, hailed by John Banville as “an extraordinary, overwhelming book”.

With one of the most finely tuned ears in contemporary fiction Ford explores the big issues of our time with a disarming use of the vernacular. Born in Jackson, Mississippi in 1944, Richard Ford is the author of six novels and four collections of stories. Independence Day was awarded the Pulitzer Prize and the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, the first time the same book won both prizes.

He talks to Artistic Director of Sydney Writers’ Festival, Chip Rolley.

Bertrand Russell and Niccolo Machiavelli

Will one of you smart people, please put me right on this?

The Prince is a handbook for gangsters, he said, or did he?

“Democracy” is “motherhood” these days.

Today they would be extolling Comrade Number One in North Korea and telling us that the people of North Korea support the regime. Just look at those televised spectacles.

Everyone is a democrat, but what is “democracy?”

Icaria at Corning in Utopian Iowa

The school was orignally built for another community. When that community failed it was given to the Icarians and moved to Corning. There were three subsequent moves and that explains the mystery of the moving school.

The Icarians who went west from Nauvoo settled in Corning Iowa on the Nodaway River.

http://www.icaria.net/

Arcosanti, Utopia in the desert

The Plan is everything, or is it?

Utopia in the desert.