1863 The Red Cross was founded at a meeting in Geneva, stimulated by businessman Jean-Henri Durant and lawyer Gustave Moynier. There were eighteen government delegations from Europe and many individuals. These two men influenced the Swiss government to host and sponsor this and future meetings. We donate blood whenever we have any to spare.

1923 Mustafa Kemal Atatürk declared Turkey a republic (Türkiye Cumhuriyeti). I discussed a biography of this remarkable man elsewhere on this blog. We spent a fascinating two weeks in this museum of the world.

1945 Gimbel’s department store in New York City (1897-1987) sold first Biro ballpoint pen for $12. About $170 today. In Argentina Hungarian refuge László József Bíró found a way to get the ink to flow yet be dry on paper. It first went on sale in Buenos Aires as advertised below. A version of this was the (Milton) Reynolds Rocket sold by Gimbels. Its sales matched its name, selling a thousand in one day. (Marcel Bich bought the patent and now we have BICs.)

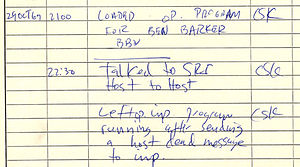

1969 First computer-to-computer link was established in ARPANET (Advanced Research Projects Agency Network), forerunner to the internet. The aim was to combine computers to magnify the computing power available at any one place for research. Below is the log of the first successful message. Contrary to legend it was not designed in the hope of withstanding a nuclear war.

1982 Alice Lynne Chamberlain was convicted of the murder of her child with circumstantial evidence. The media frenzy was a grotesque tsunami of bile. The dingo had more defenders than Ms Chamberlain. The stronger she was in the face of adversity, the more the media attacked. Decades later the conviction — produced as much by trial by media, as by evidence — was quashed, and she was paid compensation for a ruined life. Meanwhile, the mediaistas gave each other awards for their unscrupulous sensationalism.

28 October has a past.

1636 Harvard College was founded. It was the first institution of higher learning in United States. Spent a semester there, deep in the basements of Widener Library.

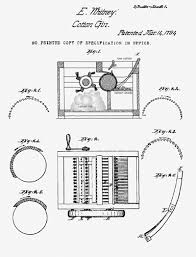

1793 Eli Whitney applied for a patent for the cotton gin, ushering in the planation and slave economy of the south in the United States. He got the idea from seeing a cat scratch at its fur to get burrs out. When cotton could be cleaned efficiently and effectively, then large scale production made sense.

1916 First Australian referendum on conscription for military service in the Great War was defeated. The event is so encrusted with later appropriations and self-serving distortions it is hard now to grasp the issues as they were seen at the time.

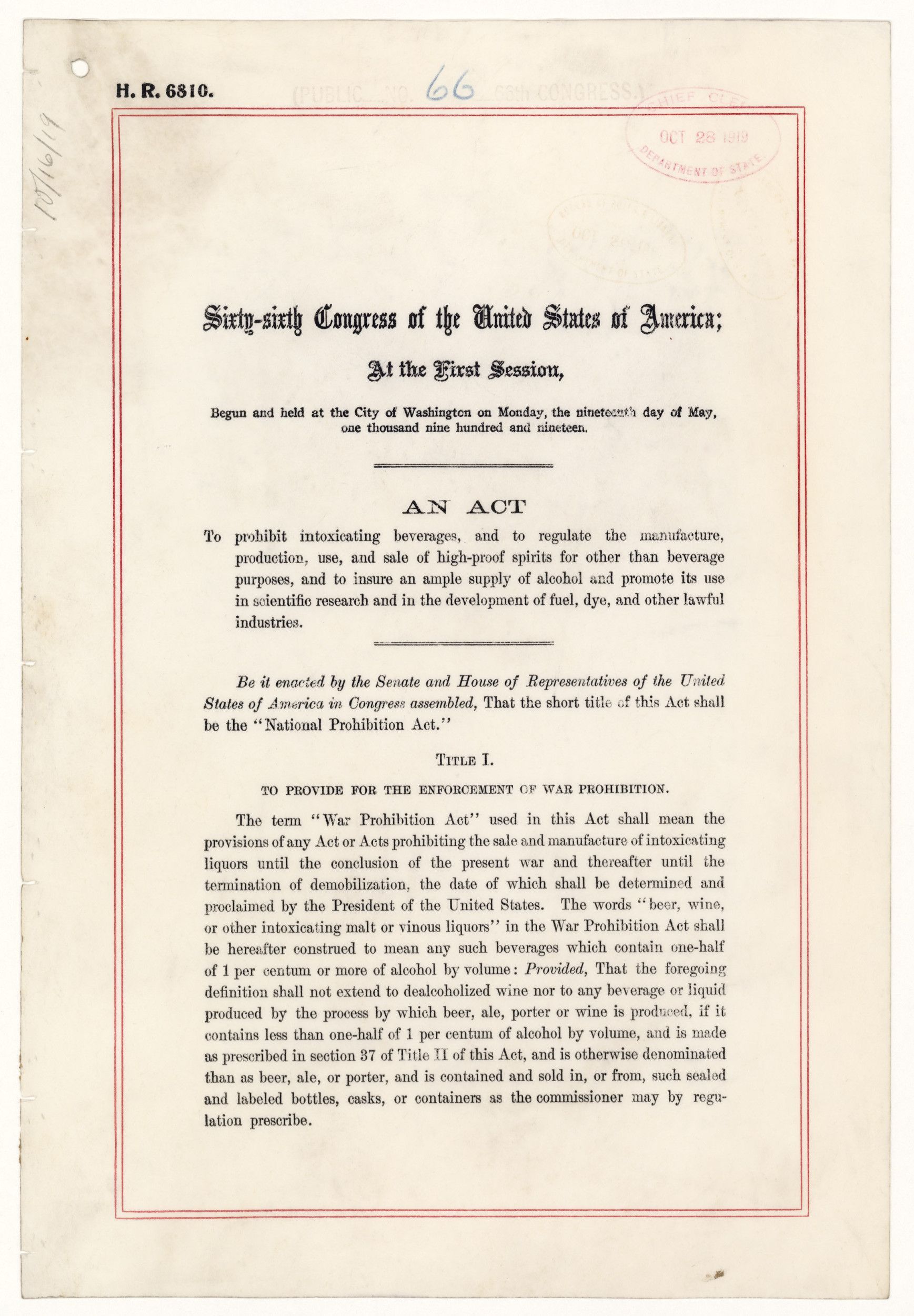

1919 United States Congress passed the Volstead Act to enforce the 18th Amendment which had been ratified by 36 States. President Woodrow Wilson had vetoed the act earlier and it took Congress but three hours to override with a two-thirds votes. It was repealed in 1933.

1998 Glen Murray was elected mayor of Winnipeg, population 600,000+. He was homosexual and said so. He later held several provincial cabinet portfolios until retiring in 2017. The sky did not fall. Been there for a conference once upon a time.

‘The Black Doll’ (30 January 1938)

IMDB meta-data is runtime 1 hour and 6 minutes, rated 6.2 by 77 cinemitizens.

Genre: Old Dark House.

Verdict: Much better without the sheriff.

Henry Gordon is a marvellous bad guy, who reeks malice and laughs as others fall down. In short, the fraternity brothers warmed to him immediately. His great fortune came from a mine in South America.

He lives with his sister who has two adult children, too lazy and stupid to move out, a very young William Lundigan who made the mistake of trying to act, and a very fey Nan Grey whose acting was irrelevant. She has taken up with the very pleasing Donald Woods, who for once plays the lead. Then there is the kindly doctor, Holmes Herbert, who is much in attendance.

One look at the greasy Gordon and we know he got the mine by foul means. He knows it, too. When a black voodoo doll lands on his desk, he gets the message.

Then he get a sharper message in the back. To know Gordon was to hate him in the words of the song, but who got to him first? That is the question. The business partners he cheated out of the mine? The sister that he keeps captive? Her son, Lundigan, who owes gamblers money? The butler whom Gordon has treated with contempt for years? The pet canary that has been caged since forever? Nan, the niece, who wants free of the past Gordon represents? A boy scout doing a good deed? A stranger off the street? Or none of the above?

Pop quiz! Remember who was much in attendance above?

Nan has a picnic with Dan, and they play detectives with the pet Westie. There is another brilliant scene when Nan runs through the rain, and really does get wet, to find Dan and runs into the villain….

Regrettably, as the local sheriff Edgar Kennedy almost ruins it all. Don’t blame him. He was woefully miscast and systematically misdirected. Yet he dominated the second half. The fraternity bothers are never comfortable with authority figures, but Edgar they accepted, since he had no authority, no gravitas, and no brains. He took over the dumb-as-a-post duties often assigned to black stereotypes or women in films of this time. For that we owe him thanks.

‘Mars Attacks!’ (1996)

IMDb meta-data is runtime of 1 hour and 46 minutes, rated 6.3 by 191272 time wasters like me.

Genre: Sy Fy and Self-Indulgence

Verdict: Cut! Cut! Cut!

‘The Martians are coming!’ ‘The Martians are coming!’ ‘The Martians are coming!’

Got it.

What is worse they are just like the fraternity brothers, stupid, cruel, rude, ugly, and relentless. About twenty minutes too relentless.

One fine day an ensemble set of characters from a big cast list discovers that ‘The Martians are coming!’ and react to that in different ways. That is the first half. Some are afraid. Others hopeful. Some don’t notice. Others don’t care. Scholars rush to speculate. Talking heads do.

Then the Martians come and exploding heads follow. Many exploding heads. Many, many, many. And then some more. Second half.

In the first half a weak-kneed liberal president concludes they are coming in peace, though no one wonders why it takes so many of them to come in peace. Every courtesy is extended including overlooking the slaughter of the first welcoming party. There follows more slaughter and more forgiveness. Is there a parallel to the weak-kneed native indians who kept trying to cooperate with the white man and got slaughtered for their trouble. It seems an obvious comparison but it is not made here.

In the second half it is all out war. Except none of the weapons Earthlings use do any good. Not even the method acting of a geriatric Rod Steiger which killed any interest the fraternity brothers had in the film. Fortunately, the Martians are none too smart and it takes them a long time to murder everyone. What losers!

There are tropes from a host of other Sy Fy movies, including the bulbous noggins of the Martians and the flying saucers over D.C. A few of the vignettes are amusing; most are not.

While the actors are uniformly good, they have very little to do. The script after all was derived from bubble gum trading cards. The characters betray their cardboard origins. Viewers will long for the depth of insight of a comic book.

Martin Short as the slime-ball press secretary is great. That Jack Nicholson is president seemed a welcome relief in 2018 since he gives the role gravitas. Pierce Brosnan never looked more sure of himself than when he was totally wrong time after time. Perfect. Annette Bening lit up the screen. As always, Jim Brown brought dignity to the Las Vegas Egyptian costume (which one dolt, a professional reviewer at that, said was Roman) and Pam Grier evidently thought it was a drama and gives a fine performance that should have been in another movie. ‘I’ts not unusual’ that a big chunk of $70 million budget must have gone to the performers. The writing is less than Ed Wood standard. Much less.

On the plus side no one thinks the response to the Martians’ assault should be prayer. Regrettably Whit Bissell is nowhere to be seen at a lab bench concocting a double whammy to lay those Martians low as he did in so many 1950s Sy Fy films. On the minus side it is a long list but it always comes back to one thing: the lack of a narrative. We don’t care about the characters because they are so cardboard, and the situation is repetitive, and the denouement is nice but much, much too long time in coming. Way too long.

There are many loose ends. The apocalyptic opening scene with the stampede of burning cattle is never resolved. It occurred long before the first Martian left Mars. It seems to have been forgotten by the director, along with much else.

We never do find out why the Martians came. Sure, just for fun, but why then? Why not in 2016 when we really needed a diversion.

Are Kansans really as deplorable as they appear to be in this movie?

We have a lot of camera time with the first daughter and then she is seen no more. Moreover, she would seem to be more like a grand-daughter to the geriatric president.

Did Jack Black have to be in this movie at all? (This is always a question worth asking.)

The Martians seem particularly to dislike birds. Why? We’ll never know but a point is made of establishing it.

What colour socks do the Martians wear? (One of those searingly insightful media questions.)

As to any and all of the above, who cares?

27 October in history

1275 First recorded mention of the village of Amsterdam. Been there many times and read Geert Mak’s ‘Amsterdam: a Biography’ (2001).

1659 Quakers William Robinson and Marmaduke Stevens who fled England in 1656 to escape religious persecution were executed in the Massachusetts Bay Colony for heresy. Good Christians everyone.

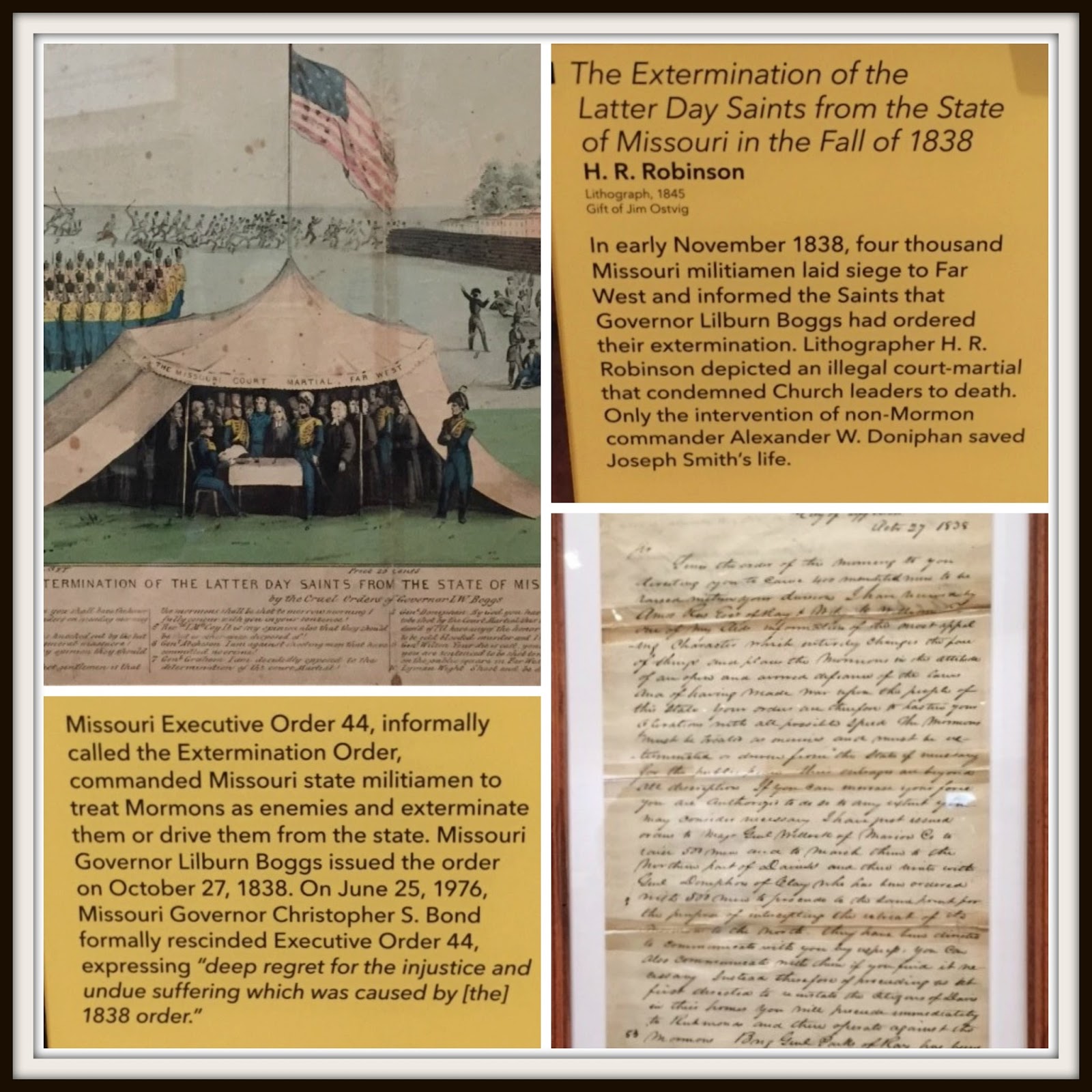

1838 State of Missouri ordered the extermination of all Mormons in the Missouri Mormon War. The survivors went upriver to Nauvoo and there followed the Illinois Mormon War. They then went west to Utah, where followed the Utah Mormon War. Good Christians everyone. N.B. Etienne Cabet bought Nauvoo from the Mormons for his Icarian followers. Been there a couple of times on the very Big Muddy.

1938 DuPont Corp announced the new synthetic fibre, nylon. It was used for toothbrushes at the start, replacing hog bristles. Shortly thereafter it went into stockings, and it had a patriotic patina because the silk for silk stockings came through Japan. Choosing nylon rather than silk was the American choice in that trade war.

1954 ‘Disneyland’ premiered on television, which included Frontierland and Tomorrowland. Watched it every Sunday night for years. Read a biography Walt Disney which is reviewed elsewhere on this blog: Michael Barrier, ‘The Animated Man’ (2007).

‘Stowaway to Mars’ (1936) by John Wyndham.

It has also been published as ‘Planet Plane’ and ‘The Space Machine’ under the name John Beynon.

Genre: Sy Fy

GoodReads meta-data is 189 pages rated 3.23 by 525 litizens.

Verdict: What a relief, it has punctuation.

In far distant 1981 there have been Moon orbits but no landings. Why bother, there is nothing there but moon rocks. George Soros has put up millions as a prize for the first flight to and from Mars. Some have tried and failed. Pundits are sure spaceflight is impossible, and publish their opinions as facts on Faux News where Soros is likened to satan since both words start with ’S.’ It was ever thus.

Dale Curtance of the Boeing family builds a rocket in his backyard to win the prize. He is motivated by glory since he already has enough money to build as many rockets as he would like.

Dale is every director’s leading man, fearless, chiseled chin, handsome, genial, sexist, and quick with a shooting iron. He assembles a crew. There is an ageing doctor, an annoying journalist, a navigator who has never been out in space before, and an engineer who is permanently angry, and a stowaway they soon learn. What a carefully picked crew! The doctor will study the flora and fauna. The journalist will keep a factual log. (Fiction to be sure.) The navigator does nothing. The engineer sulks. Dale is fully occupied with chin maintenance. Then the Gloria Mundi blasts off for three-month trip to Mars where they will land and from which they hope to return.

The stowaway is Joan who has come to help. Help? How? By translating Martian. Huh? It seems is a six-legged machine showed up at her father’s farm and she learned Martian from it. Well, so she asserts since no else but Joan and Dad saw the contraption. Those two were sure it was not of this world. That it was intelligent. That….. It did not communicate and yet it did. So goes the circle. Then it vaporised itself. (If only Faux News would do that.) They were convinced it is/was an ambassador from Mars. Having studied the markings on the machine, Joan now feels qualified to translate from Martian. She qualifies for President Tiny’s cabinet with that grasp of facts.

The 1930s sexism is piled on without remorse. Joan is belittled, assaulted, patronised, insulted, and still expected to clean the coffee cups. In fact, this oppression is so detailed, a reader might begin to suspect Wyndham of irony. Or is that too long a reach? Hmmm. See below.

Mid-flight there is a seminar on the relationship between man and machine, and that is man, not woman. It is superficial, vague, and unfocussed enough to be one of those panel discussions on the ABC. They never once refer to the spaceship in which they ride as a machine. Indeed, there is no reason for them to blast off if this is all they have to talk about. Though it becomes relevant, sorta when they get to Mars.

Mars is almost entirely populated by AI machines because the human-like Martians are dying off. There is a declining birth rate, no doubt due to Hillary Clinton, and ever lower resistance to disease, thanks to the anti-vaxxers among them. The remaining Martians see the continuation of the machines as the natural order of evolution and accept it. One tries to explain this attitude to an Earthling, who goes all Luddite and chews an Opal card. This is the most interesting part of the book, but Wyndham had not yet hit his stride and it is talky, talky, and talky. In it, however, Joan is proven right about much for which earlier she was ridiculed by the blokes. That is why I wondered if there was irony in the way the misogyny was laid on. (Albeit there are loose ends, i.e., I never did figure out who sent the machine to Joan’s farm.)

John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris

was the son of a barrister. After trying a number of careers, including farming, lawyering, and advertising, he started writing short stories in 1925. This book was fifteen years before ‘Day of the Triffads’ (1951) and nearly twenty years before ‘The Midwich Cuckoos’ (1957), which became the film ‘The Village of the Damned’ (1960). In these he certainly hit his stride. Each is unique and unforgettable.

What’s so great about 26 October?

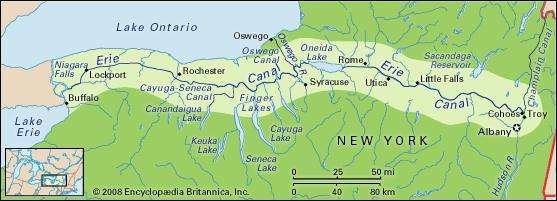

1825 The Erie Canal of 363 miles opened, connecting the Great Lakes with the Atlantic Ocean via the Hudson River. It produced an economic boom along its route and made Buffalo a sea major port for products from Chicago and points west as well as from Canada. It is often forgotten that the United States has northern and southern sea coasts. I have been to Syracuse and Utica on the route.

1905 Sweden conceded independence to Norway in a peaceful though rather fraught conclusion to tensions. Pictured below is a monument to that event. Been to Sweden a couple of times but want to go to Norway to see the giant paper clip. Yep.

1922 Gertrude Bell (1868-1926) was appointed Head of Antiquities in Baghdad, one of her very many claims to fame. In this job she organised the systematic identification, documentation, and preservation of the human heritage to be found there. She also did some of the finding. She was here, there, and everywhere in the Middle East.

1958 Pan Am began flying passenger jets from New York City non-stop to Paris in a Boeing 707 which made the world smaller, and smaller. There was a brass band send-off. I flew with Pan Am once.

1986 Bill Bruckner entered Baseball’s Hall of Infamy. Mookie Wilson ran out the ground ball, as few millionaire players do today while the white ball eluded Bruckner’s glove and the Red Sox found another way to lose. Members of the Red Sox nation have forgiven but not forgotten this error. Seen the Green Monster with my own eyes.

25 October – What a difference a day makes!

1415 Henry V at Agincourt prevailed over a French force five times larger with the long bow made from Welsh Yew wood. The elasticity of the yew gave the bow a range greater than anything else, making it the artillery of the day. Its arrows struck with sufficient force to penetrate a knight’s armour. It was good night for the knights. Hundreds were killed before they came within range of their weapons. Hundreds more were killed after surrendering.

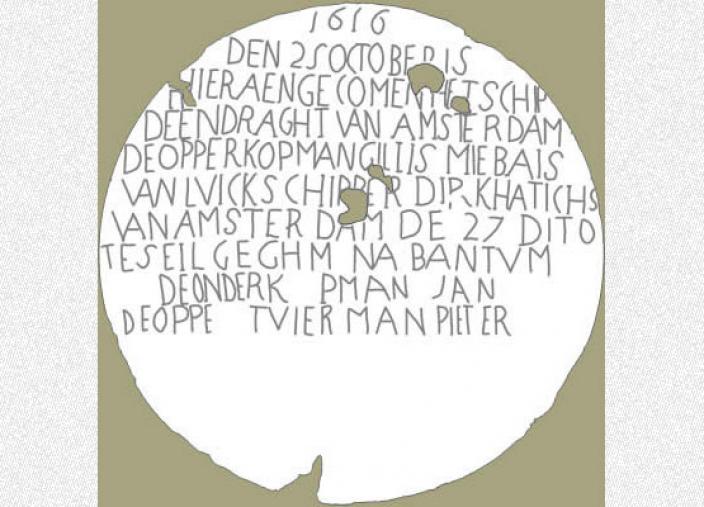

1616 Dutch sailor Dirk Hartog became the first recorded European to set foot on Australia’s western coast, and he left a message at Cape Inscription, Western Australia.

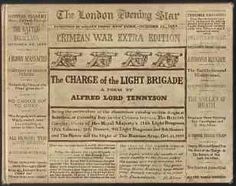

1854 At Balaclava the Light Brigade by mistake charged into death and legend.

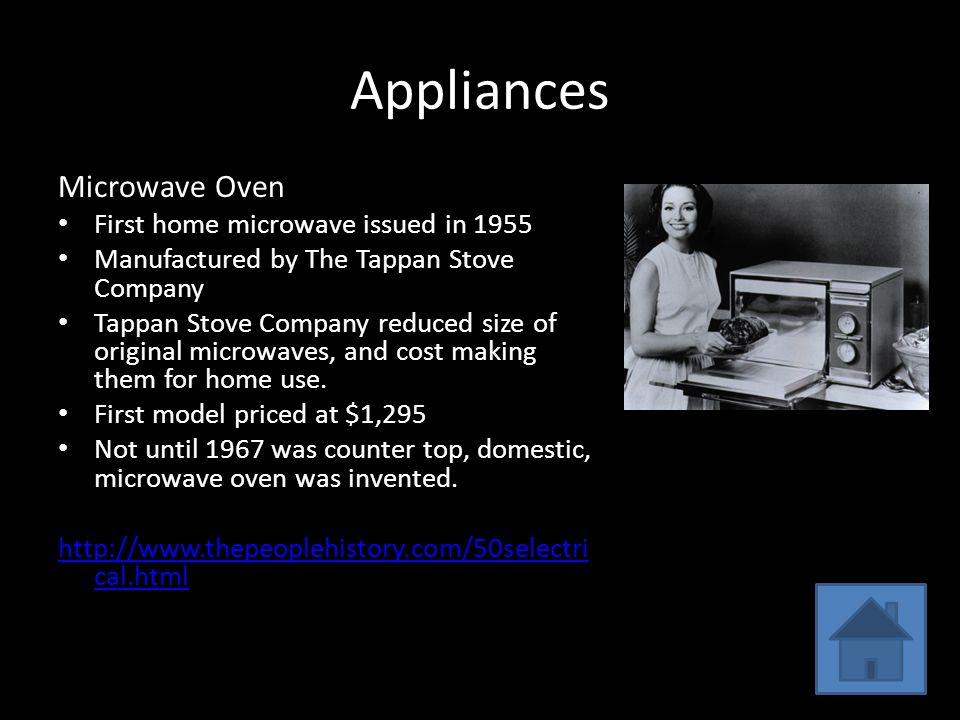

1955 The Tappan Stove Company sold the first microwave oven. It was wall mounted and in today’s US dollars cost about $12,000. It weighted about 700 pounds. The wall and the weight were insulation.

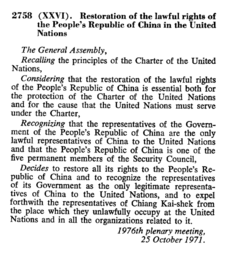

1971 United Nations seated People’s Republic of China and to expel the Nationalist government of Taiwan.

24 October

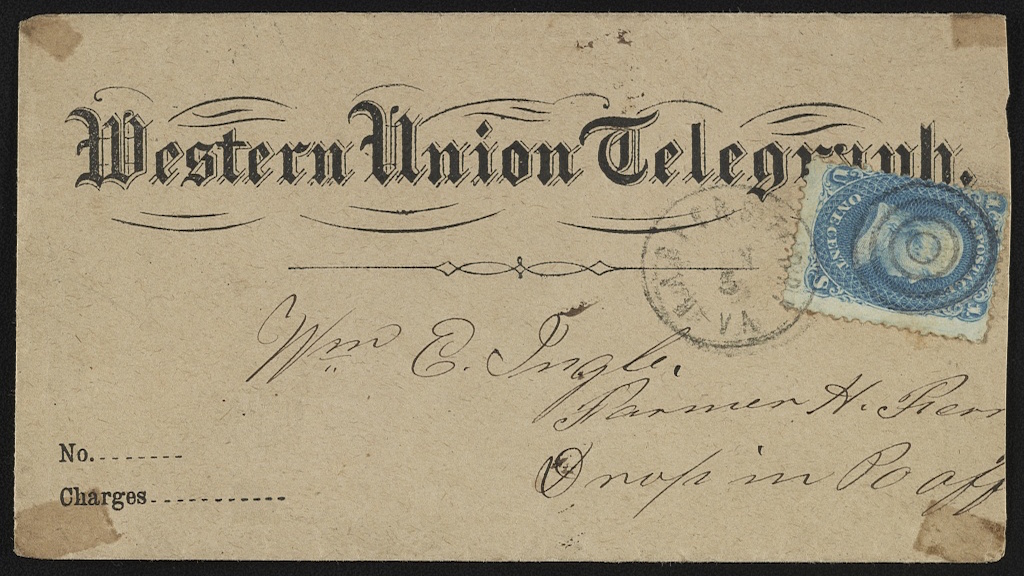

1861 Western Union sent the first telegram coast-to-coast in the United States from San Francisco to Washington D.C. The message had to be repeated along the way.

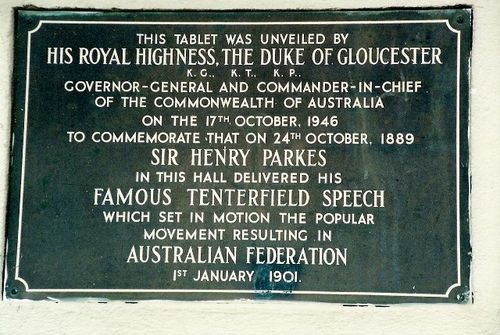

1889 New South Wales Premier Sir Henry Parkes called for federation of the Australian colonies at Tenterfield in NSW. He continued to argue the case for unity thereafter. He was the first, loudest, and most consistent advocate of Australia as a single entity on economic, defence, and moral grounds.

1897 First newspaper comic strip appeared in the New York Journal, ‘The Yellow Kid.‘ This rag was a Hearst newspaper printed on yellow paper, as the Financial Times today is printed on pink paper, leading the Hearst press being called Yellow Journalism as short hand for the Fox News of the day.

1929 Black Thursday – the first day of the stock market crash which began the Great Depression. Thus began the Great Depression that lasted for a decade. So far Hillary has not been blamed for this.

1946 The U.N. charter was ratified by the then 5 permanent members and 46 member states. The agencies of the UN have done much good since then.

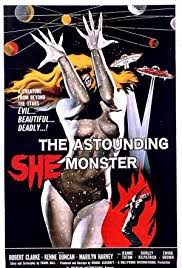

‘The Astounding She-Monster’ (1957)

IMDb meta-data: 1 hour and 2 minutes (it seemed much longer than that) and rated a generous 3.3 by 686 dopes.

Genre: Sy Fy and Bore.

Verdict: Two good things about it are: It does not star John Agar and Robert Clarke keeps his shirt on.

The stooges kidnap an heiress and head to the high Sierras for a spot of ransom. Sounds far better than it is. While this is played out in slow motion, or so it seemed, a flash of light in them thar hills occurs and then a woman in a skin-tight body suit with exaggerated eye brows walks from the woods to the out of focus camera. She stays out of focus. She walks like she has the OED balanced on her head. Carefully.

The inference is that she is an alien emanating a blurred aura. The fraternity brothers like the skin-tight part but not the blur. However the blur was probably necessary to get the picture aired in the time of the Hollywood code.

To sum up, she wanders around the woods killing everything and everyone she meets. A dog, a man, a bear, a woman, a butterfly, a fox, another man. Obviously she is an American diplomat come to make the peace of the dead. I kid not. Read on.

Meanwhile the three stooges have holed up in the aforementioned Robert Clarke’s mountain cabin where he practices taking his shirt off and on away from prying eyes in readiness for his performance — is that the right word? — in ‘The Incredible Petrified World’ (1959), reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Two of the stooges have gats and Clarkie has little choice but to comply. He complies. At times they combine to fend off Skin-Tight, but she picks them off one by one, until….. Spoiler coming.

The pollution in Earth’s atmosphere kills her. Whew! Thank you H. G. Wells for suggesting that in 1891.

But wait there is more!

The locket Skin-Tight wore was not an intergalactic fashion statement after all for it contained a message written in copperplate English handwriting, declaring her to be an ambassador who has come in peace! Pause.

Just think, someone got paid — not much we may hope — for writing this.

How will the home-world react to the death of this ambassador. Will another come? A bigger, a badder, a meaner one? The End. Was a sequel planned? Does it exist? Can it be avoided?

Does it sound like ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ (1951) without the depth? Yep a derivation which these days is called ‘reimagining,’ i.e., trivialising with CGI.

Nota Bene. This ambassador made no effort to communicate but her touch was fatal to everything. The opening voice over went on about cosmic retribution which was heard by the minority paying attention, but this is never squared with the peaceful mission revealed after the body count at the end.

The young heiress looks about fifty. The two goons and their moll look retarded. The direction looks zero. Once the actors are on their floor marks, they stand still to retain camera focus. There are voiceovers which indicate the lack of a sound engineer. Perhaps 90% of the film is in one nearly bare room. Cheapo. For the drive-in market where no one would see it.

Robert Clarke grew up in Oklahoma movie struck from a young age. He tried hard and seems affable enough on screen, and much more alive than say John ‘Oak’ Agar. Clarke’s other credits include ‘The Man from Planet X’ (1951), ‘The Incredible Petrified World’ (1959), and ‘Beyond the Time Barrier’ (1960), which are reviewed elsewhere on this blog. What a Sy Fy CV. He never made it in movies and like many other B-movie actors he went into television where he compiled many credits.

The fraternity brothers talked me into watching this one and they will pay for that when I read long passages from Martin Heidegger to them while they eat. Indigestion is sure to follow.