IMDB runtime is 1 hour and 13 minutes, overrated at 3.5 by 648 cinemitizens.

Genre: Sy Fy and nothing but.

Verdict: One of the first Eye-tie Sy Fy but not the last. Alas.

In the year 2116 Rik van Nutter….[ponder that as a stage name] is assigned by the ‘Interplanetary News’ to visit a space station, one of several, it seems, and do a series of human interest articles, about the crew members, their work, life in space. That might seem a reasonable set up.

Here is how it plays. Rik is an insufferable know-it-all, busy-body, girl grabber, and endless pain. He has barely set foot on the station when he starts telling everyone how to do their jobs, getting in the way, and complaining about everything from the soup to the nuts. (Couldn’t resist that one.) After that he gets quarrelsome.

Even the ever whining fraternity brothers grew weary of Rik at 10 minutes and 05 seconds.

His initial meeting with the botanist sums it up. He astounded that the botanist is a woman. He astounded that a woman is a scientist. He is astounded that a woman is an astronaut. He is astounded that a woman is doing vital work. He is astounded that a woman is content to wear the work coverall that all the men wear. He is astounded….

After belittling her work, disparaging her capacities, and insulting her tastes, he turns on the charm and begins to grab and grope her in his state of astoundment. That was then. But what can one say? Has anything changed?

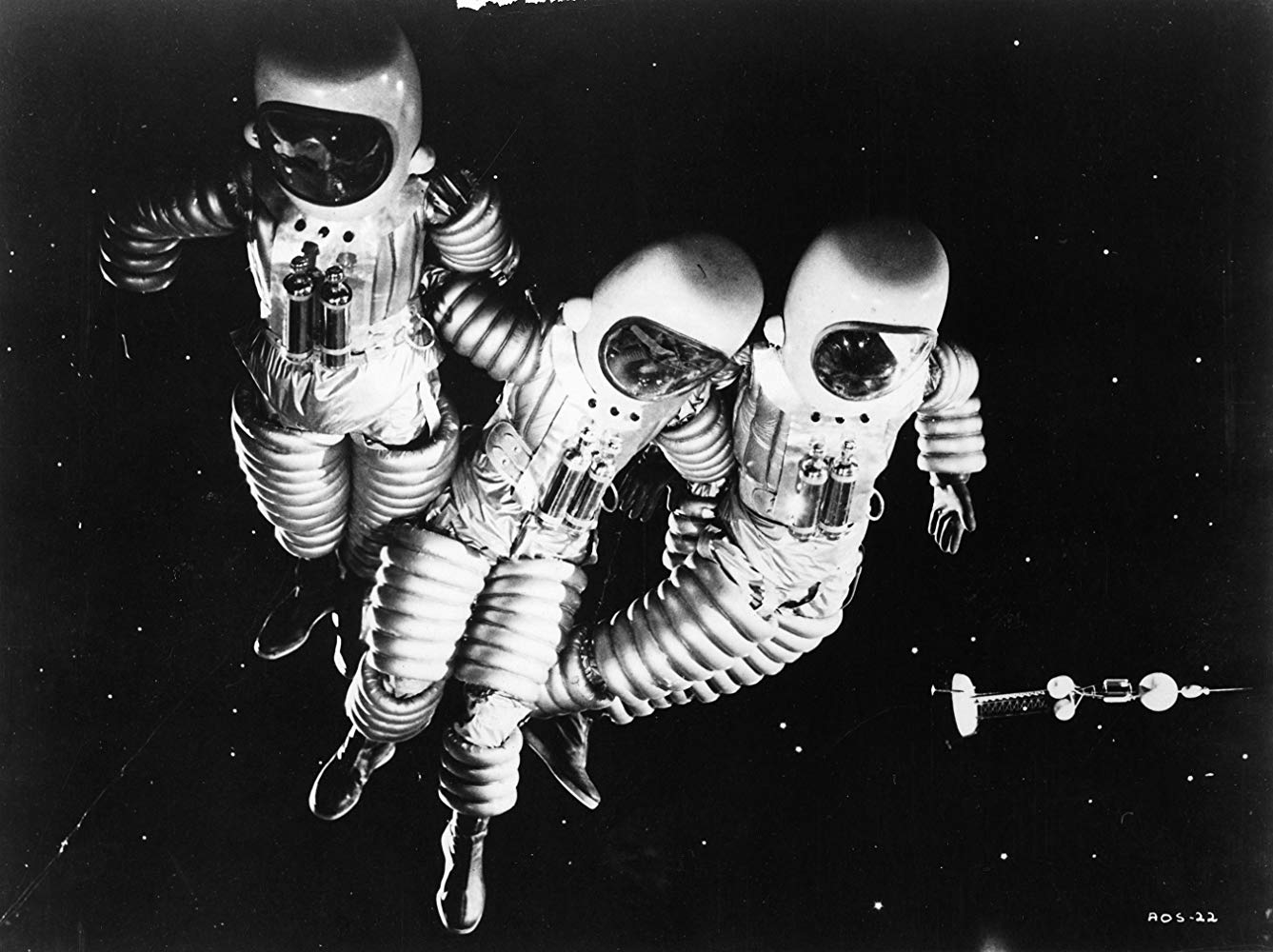

There are some nice shots of weightlessness.

Though why they wear bikers’ helmets all the time is anyone’s guess. Still the white helmets with the dark sun screens make nice images and were cheap to hire.

The station is on a routine maintenance mission when things go wrong. Right on cue the meteors shower up. In part the accident happens because Rik got in the way, but he is sure he saved the day in so doing. In between pouting sessions he declares his heroism and demands a parade in his honour. He goes around expecting to be thanked. He is royally pained to discover the crew is too busy doing important work to celebrate him.

Never does he ask anyone else about themselves, about their work, or write a note. No doubt to complete his story when back on Earth he will interview another journalist and go from there. Some things never change.

To add colour, so often lacking in Sy Fy, Kmoto is there to make sage remarks. He makes the banal lines he has sound important. This one is not all white-bread. Noted.

More things go wrong and this crew has to save the world. None of them are up to the job so Rik has to do it. Ho hum.

This was director Antonio Margheriti’s first solo foray into Sy Fy.

In this outing he took the English pseudonym Anthony Daisies, but Sy Fyians know him better as Anthony Dawson of the Gamma 1 sequence, reviewed elsewhere on this blog. It was with this picture that Mr D proved he could make a movie in ten days for ten lira, and off he went to do for the next fifty years. His last credit was in 2010.

‘The Night of the Comet’ (1984)

IMDb runtime 1 hour and 35 minutes, is rated a miserable 6.5 by 15020 cinemitizens.

Genre: Sy Fy. Horror. Comedy. Fun.

Verdict: The search for intelligent life on Earth ends in the San Bernardino Valley.

Once every sixty-five million years a big red comet passes close by Earth. Get it? Last time it called, dinosaurs exi(s)ted.

It is Christmas Eve and everyone wants to see the red comet, being all Republicans they have no knowledge …. of extinction events or anything else. Everyone who can, stands outside to watch the comet fly-by. The red light shines and life is eradicated. Anyone exposed to the comet’s red glare turns to calcium dust. An improvement for the moral majority.

Some who were partly sheltered slowly turned into Pat Robertson zombies. A few who happened to spend the relevant hours in a tightly sealed, steel-lined room are uncontaminated. That latter number includes theatre projectionists, quiz show participants, survivalists, garden gnomes brought into sheds at night, truck drivers sleeping in the back, and …

Two Valley girl sisters survive and want to keep doing so. They have plenty of training from soldier dad, who is away fighting Sandanistas ‘in Honduras.’ Hey, don’t blame me, that is what is said. Apologies to everyone in Honduras but maybe dad was on R and R there.

In their search for life, they hear a radio station DJ broadcasting, so they go to the station. There they find a tape on a loop. The DJ taped the graveyard shift program in the afternoon and went home. He might have survived had he been in the airtight station booth. That same tape also lured Commander Chakotay. They team up, a little. Not enough, cried the fraternity brothers.

The girls show a few zombies some moves and break into NRA headquarters for some heavy weapons. Thus prepared, they head to the mall. The fashion parade cum shopping spree is great fun until the zombies come to the party which disintegrates into an NRA shooting spree. The fraternity brothers thought they recognised a couple of Sigs among them.

Just when it seems things cannot get any worse – Remember ‘Deer Hunter’ (1978) – they do. They are rescued by a crack team of GOVERNMENT scientists. Much relief… is short-lived. All those capital letters mean trouble ahead.

The scientists are more interested in…. [spoiler].

However Commander Chakotay comes to the rescue, and the girls again put their dad-training to good use. The fraternity brothers chortled when the lab assistants were tied up with the Santa Claus sign.

But best of all is the finale.

While our gang is sequestered in the desert bunker a cleansing rain falls and washes away the killer red dust and all the little calciums. A new dawn rises. After blowing up, up, and away the mad and bad scientists, aided by one of scientists who retains a conscience despite years of McKinsey-speak, our crew return to Lost Angeles….to go shopping in Eden Mall.

Chakotay and Big Hair look married, and are accompanied by the two tweenagers they rescued from the clutches of the lab assistants, they make a family. Many selfies are taken with a Polaroid. (Remember them?)

They dance down some steps to the street and stand at a crosswalk waiting for the light to turn green so that they may cross. No spoiler. But the next few minutes are worth the price of admission. Delicious and delightful.

Impossible not to like.

Thank you Thom Eberhardt, writer and director.

It is energetic, full of tributes to other, better movies; fast and furious; has some ripper one-liners, the mandatory 1980s fashions, big hair, big teeth, and Mac30s. Loved it when the gal pals compliment each other on their rigs in between slamming would be zombies to the ground and cutting others in half with a hail of sound effects.

Commander Chakotay breaks two of the barriers to Sy Fy, being Latindio. Get it? And one of the tweenagers might be Sansei plus. It is rare for Sy Fy to be anything but white-bread.

The empty street scenes in Lost Angeles were shot on Christmas Day and then scrubbed, say the reviewers.

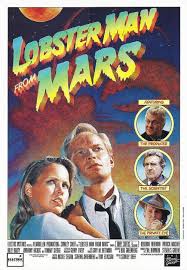

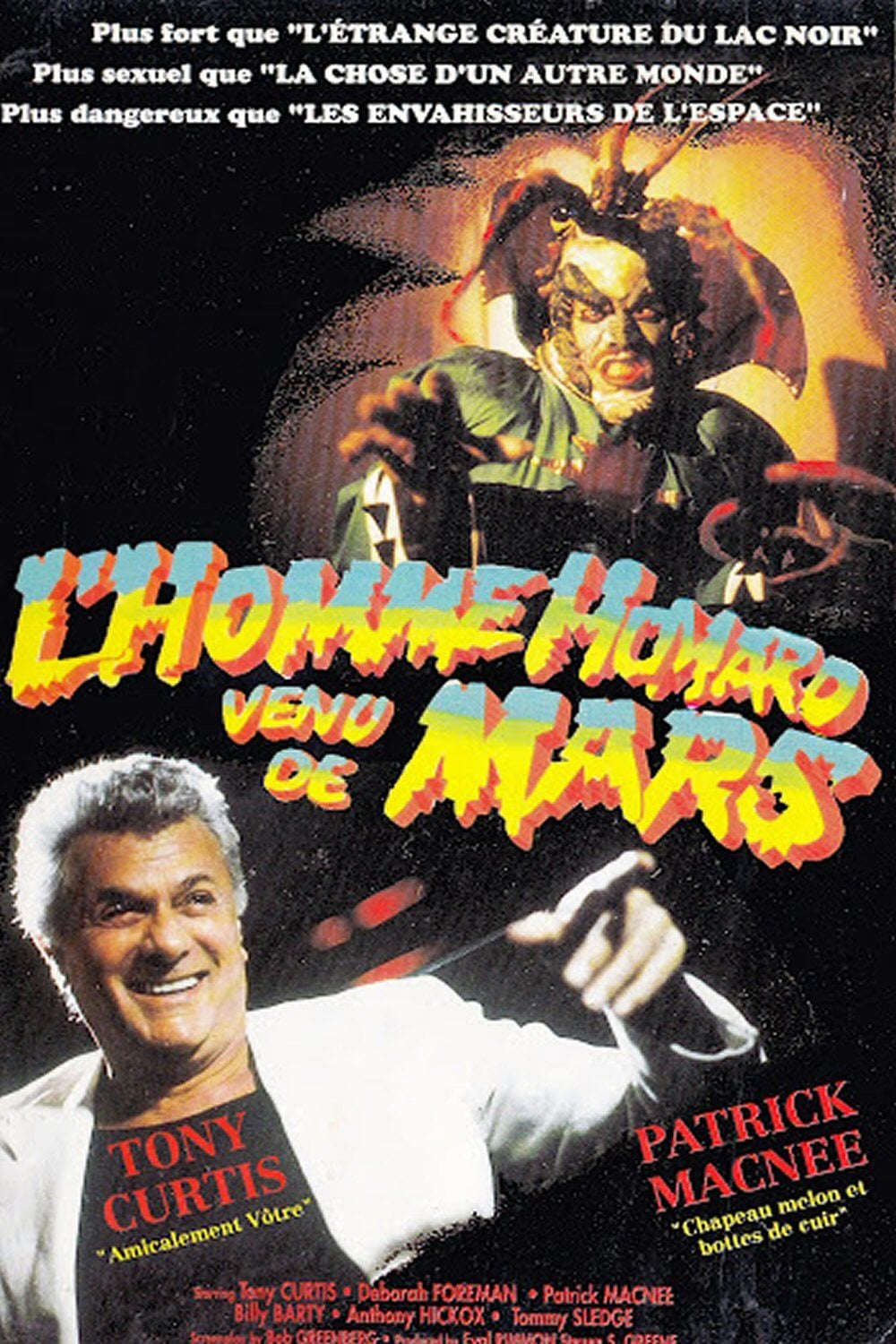

‘The Lobster Man from Mars’ (1989)

IMDb meta-data is 1 hour and 22 minutes of treacle time rated 5.5 by 500 relatives of the cast and crew.

Genre: Sy Fy and Boredom.

Verdict: 0 and this despite the star-studded cast of John Stead, Tony Curtis, Niles Doppelgänger, and Valley Girl.

The trope is a movie within a movie, the former is sold to producer Tony as a tax write-off that becomes a hit. Mel Brooks did this better with ‘Spring Time for Hitler,’ recalled the fraternity brothers.

Sounds no better in French.

Sounds no better in French.

The within movie has the rest of the cast and the rubber suits from Parties R Us. The Martians are running out of air so Lobster Man is sent to Earth to collect air and return with it in his overnight claw. Once there, LM drifts off-mission to hunt down and consume Niles and Valley Girl, who rush back and forth in the 1950s movie nightmare they inhabit. They are shadowed by a PI who repeats invented 1950s PI slang tirelessly and tiresomely.

‘Inane’, ‘inept,’ and ‘pointless’ are some of the kinder things the fraternity brothers said of it. Tony enlivens about seven minutes of screen time before fleeing to the pay window. Stead has no more before making the same move. He also appears in another Sy Fy spoof I have been unable to finish. Saving it for much later. With these two absent that leaves more than an hour…. zzzzz. It is a long cast list and one suspects the contracts stipulated entering a ten vote on the IMDb web site.

Read that stub carefully and believe it, or not: Sundance!

Read that stub carefully and believe it, or not: Sundance!

That a movie is so bad it attracts a following of idiots from among the rich pickings of idiots out there is the wet dream of every inept filmster since the late Ed Wood, Jr. Ed, you have a lot to answer for.

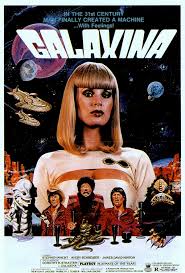

‘Galaxina’ (1980)

IMDb meta-data is 1 hour and 35 minutes of Dali time, rated 3.5 by 2285 generous cinemitizens.

Genre: Sy Fy and Boredom

The Verdict: Bad enough to be Italian.

On a deep space United Worlds (or some such nomenclature) police cruiser the crew is Captain Dorito, Cigarman, Stetson, and various rubber masks rejected from Star Wars. The ship is run by the title android, whom we style Pinocchia for reasons explained below to those who pay attention, who is perfect in every respect but is not even partly functional.

While the crew is asleep for twenty-seven years after an epic beer bash which the fraternity brothers were to sorry to have missed, Pinocchia reprograms herself to be fully functional. She is motivated by Cigarman’s lust and learns what to do by watching within copyright clips from 1970s romance films. We watch her watching these excerpts for twenty-seven years, or so it seemed, groaned the fraternity brothers. All very post-Modern meta, not privileging entertainment or intelligence over boring and pointless. Like innumerable cultural studies seminars, croaked the fraternity brothers.

While in cryogenic sleep Cigarman keeps a stogie clamped in his cancerous jaw, Captain Dorito has corn chip crumbs in his beard, and Stetson…. [go on, guess]. Fortunately, the stogie limits Cigarman’s dialogue. Good move that.

The end. ‘Hooray,’ shouted the fraternity brothers! ‘That was the best part.’

Disclosure notice: I took the dog to the park for an evening walk while it continued. Upon on return the fraternity brothers assured me that I missed nothing that they had noticed. Hmmm.

Pinocchia is eye candy for some as is Cigarman for others. Regrettably, said the fraternity brothers, the latter is the one who is undressed though this fact did not stop them faire du léche vitrine. (Figure it out.) Captain Dorito and Stetson are the comic irritants. Drying concrete is the pace. There is no screenplay apparent. The special effects were $49.95 at K-Mart.

On we go in our tireless quest for Sy Fy grail…..

‘Morons from Outer Space’ (1985)

IMDb meta-data is runtime 1 hour and 30 minutes, rated 4.5 by 1555 pathetic cinemitizens

Genre: Sy Fy Comedy

Verdict: Monty Python is an alien!

In Sy Fy-land the aliens coming to Earth are most often (1) invaders, (2) technologically advanced, and (3) rubber creatures. In this case the alien are humans, retarded, and lost. (‘Space Invaders’ [1990], reviewed elsewhere on this blog, takes a similar premise regarding the intelligence of the aliens and offers a different exposition.)

Four of these hum-aliens have rented a space pod for a holiday and are tooling around the universe; they take a wrong turn and enter the solar system. The pod is from Rent-a-Wreck and it breaks down, making a hard landing on the M4 near Bristol. One of their number got lost in the confusion and makes a solidarity hard landing in Area 51.

The Brits’ Secret Squirrels round up the trio and interrogate them for the advanced technology and alien physiology they must possess. Ah huh. These three possess next to nothing. Asking them about the space pod’s working is like asking the fraternity brothers to explain an automobile’s rotary engine: ‘There are pedals…’

Their physiology is also a disappointment. Human. And nothing but. Not even very good specimens of that.

What to do? Lock them up and let the next minister decide. Well, that is Whitehall SOP. There will always be a next minister in a year or two.

The satire is heavy. The pastiches on other Sy Fy films are several. The musical numbers are two. The social criticism floats like a sledge hammer. The pace is swift. The humour is jolly.

The American cultural attaché arrives with six-guns drawn. The Prime Directive of US foreign policy is eradication. A verity. The British minister falls in love with the alien crumpet and tries to woo her. The media vultures descend but soon grow bored with how ordinary it all is. Realistic then.

Then one hapless journalist helps the trio to escape confinement and inadvertently turns them into celebrities. They are eminently qualified to be celebrated, being vacuous, retarded, greedy, lazy, amoral, self-serving, and lacking any talent or ability. Thus they are perfectly suited to the role. Move over Paris Hilton! Realistic again.

Meanwhile, Bernard, the fourth alien, searches Arizona for intelligent life. He searches. And searches.

News of these alien celebrities reaches far Arizona and Bernard makes his way to England with the help of the Chief from ‘One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest.’ It’s not a happy reunion. The members of the now celebrity trio do not want a four-way split.

Just as muscle chucks Bernard out, there is a Close Encounter of the First Kind (hinted at in an early instrumental number) with a repo man from the Hurts space pod rental company come to collect the overdue vehicle. He takes the trio away from their adoring fans to settle the bond.

The hapless journalist has lost his meal ticket, but, well, there is Bernard. The end.

Alias Smith and Jones getting on with it.

Alias Smith and Jones getting on with it.

It is a self-parodying film, leaving nothing to add. There are some truly great deadpan performances from Dinsdale Landen and James Sikking. Mel Smith and Griff Rhys Jones have zingers and sight-gags galore in the screenplay, though it does seem like an extended skit on the television programs. Sorry lads but it is true.

Some of the humour is pie-in-the-face, which the fraternity brothers eat up.

‘Death Watch’ (1980)

IMDb meta-data is runtime of 2 hours and 10 minutes, rated a measly 6.2 by a paltry 2129 cinemitizens.

Genre: Sy Fy when it was made, fact now.

Verdict: memorable as well as prescient.

An indictment of reality television made forty years ago by a French director with an English-speaking cast in Scotland. Bored the fraternity brothers to sleep.

In the near future, medical science has eradicated nearly all diseases. Most of us die of old age in our beds. But not all. There are still some incurable, fatal diseases.

Recognising a market niche, the Television Network launches a reality program called ‘Death Watch’ which will air the final, death agony of individuals with such rare diseases. The concept is salacious, puerile, invasive, vulgar, and crass, all the qualities of a ratings winner. Coming to Channel 7Mate soon! Why do I think of Richard Carlton? (Nigel Kneale did something even more cynical in the ‘The Year of the Sex Olympics’ (1968), reviewed elsewhere on this blog.)

Filming old folks in hospice care cacking it is rejected as boring what with bed pans and all. Who wants to see wizened oldsters croak anyway.

Better that the victim is young, preferably with a tear-jerked family, and seemingly healthy before the wasting away and pain begins. The bored cynicism of the producers is heavy duty. Into the frame comes Romy Schneider. She is diagnosed and prognosed in a one shot stop.

She goes through the stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance, and shopping for the remainder of the film.

First off, the carrion eaters descend to pick her living carcass. In return for the exclusive rights to broadcast her death, the Network will shield her from the other vultures. There’s the bargain, Faustia. Surrender privacy to get privacy. Romy refuses and is besieged by the free press. She is harassed, hounded, humiliated to get reaction shots. Evasive tactics are demeaning and exhausting. She becomes a celebrity, signing autographs, getting book deal offers, and so on. That is depressing in itself.

She relents and takes the money, and then runs. She is shadowed, accompanied, and sometimes protected, and at other times manipulated by Harv who is the Network’s agent. Here is the Sy Fy gimmick, he has a camera eye. He transmits her flight back to the studio which edits and airs it. (Herbert Lom had one of those in ‘Journey to the Far Side of the Sun [1969],’ reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Didn’t do him much good. Too bad Harv did not know that before he cut his eye out to make way for the camera.)

Harv makes sure that she never realises this is going on. On the run, they are, after all, trying to avoid others, hiding out in the gloaming, darting through the heather, though not a single tam o’shanter nor a man in a skirt was sighted. These latter omissions made the dozing fraternity brothers question the claim of location shooting in Scotland. Where are the cat strangling bagpipe players, they asked.

Most of the runtime is these two leaving a grey on grey Glasgow and travelling the hinterland to the coast so that she can see the sea and die. It becomes a road movie that we have seen many times before, albeit one with a sharp edge. As Harv plays her to spin out the story, the producer manipulates him to do ever more to wring the sob out of the story. The manipulator is himself manipulated per Michel Foucault. It takes Harv a long time to realise that. Not the sharpest knife in the hack’s drawer is that one.

The mouth-breathing passive viewers of Channel 7Mate lap it up.

In this future the conditions are mostly Third World, perhaps we are all living longer but not producing more since we are watching Channel 7Mate all day. Glasgow looked better after German bombings than it does here. Most people dress in worn rags. Even the Network producer drives around in a dilapidated Leyland.

Unlike so much Sy Fy which is replete with gizmos, this one is shorn of that paraphernalia, much to the irritation of some reviewers on the IMDb. The only toy is Harv’s camera eye (and in one scene a Siri computer the size of a refrigerator). Moreover, and again in contrast to Sy Fy norms, no one is out there roaming the galaxy, but rather the focus is introspective. Additionally, it celebrates nature rather than the stars, though not quite in the same intense reverence as Edward G Robinson’s final scene in ‘Soylent Green’ (1973), not yet reviewed, because it depresses the fraternity brothers.

The musical score is perfectly aligned to the ambience. That is another departure from the Sy Fy norm where usually the score is bolted on later, priced by the minute.

That 6.2 rating puts it 0.2 points ahead of D-movies like ‘The Earth Dies Screaming’ (1964), reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Figure that out.

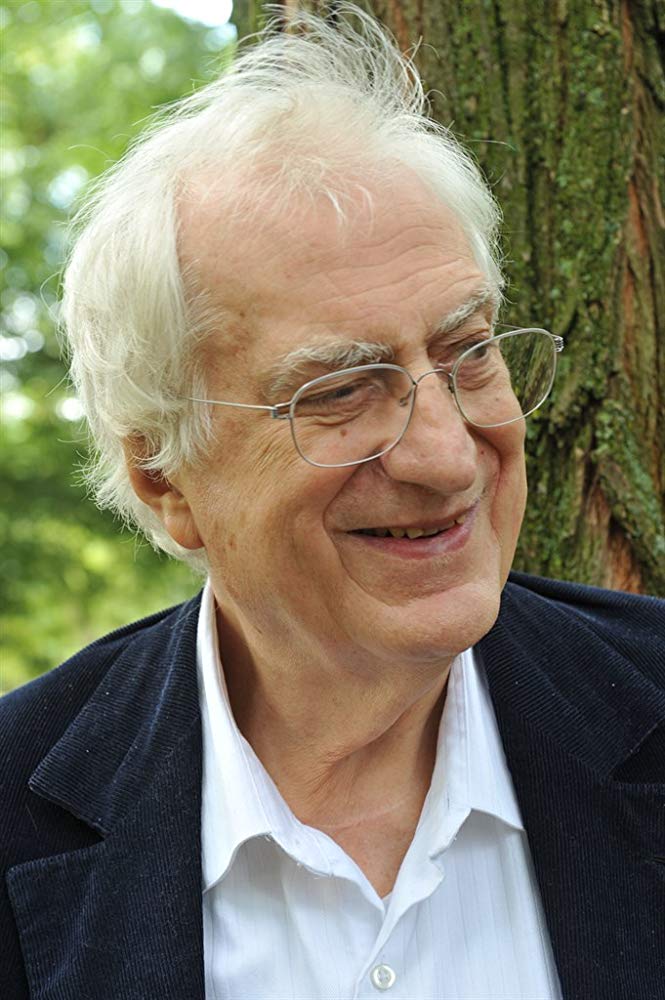

Bertrand Tavernier, lawyer turned cinemaista, is the director, writer, and producer, whatever the credits say. Like Howard Hawks, his intellectual fingerprints on a film are obvious.

There is a 2012 informative and thoughtful short interview with him about this film on You Tube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TpaVvh51Rbw). It remained as fresh in his mind during this interview thirty years later as the day it started.

Some of his other credits include these noteworthy titles:

‘Quai d’Orsay’ (2013) – a fool become foreign minister

‘In the Electric Mists’ (2009) – a mystical krimi in NOLA

‘It all Starts Today’ (1999) – a school teacher learns from children

‘Life and Nothing But’ (1989) – a bitter veteran buries the dead

‘Clean Slate’ (1981) – white savages in Africa

‘The Watchmaker’ (1972) – a father’s love is blind

For Romy perhaps the ones to name are the enigmatic Rosalie or the spectral Chantal.

‘Phantom Planet’ (1961)

IMDb meta-data is 1 hour and 22 minutes of Dali time, overrated at 3.3 by 2302 cinemitizens. (How come so many votes for this loser? Dunno.)

Genre: Sy Fy

Verdict: Davy Crockett in space!

The set up is this: in far distant 1980 the United States Air Force is rocketing hither and thither, Mars, Woolworths, Venus…per Marvin Miller’s opening voiceover. (Marv was taking time off from handing out the dosh for ‘The Millionaire.’)

Get this, the pressure suits of the astronauts (and that term is used) have the Davy Crockett touch, a fringe along the arms to keep the space flies away.

Check out the fringe down the left forearm of the dark-haired red shirt.

Check out the fringe down the left forearm of the dark-haired red shirt.

We see these same two fringed pressure suits on no less than eight astronauts, two at a time, throughout the eternity of this film. Even the fraternity brothers noticed the fringe on the fourth viewing.

One of the USAF rockets goes missing. Who you gonna call to find a missing rocket? Steve Canyon, that’s who! A bleached, gaunt, and comatose Steve, but Steve nonetheless.* He reaches for the clichés and says ‘it is too quiet’ in space. Vacuums are like that, Steverino! Maybe Steve shouldn’t have graduated from spaceboy school.

Spruced up after a meteor shower, Steve manages to lose his co-pilot in that too quiet space vacuum, accompanied by the Lord’s prayer. Yep. It takes Steve a while to notice this loss, and he recovers from the emotional trauma in seconds. That’s, Steve! Tough as nails where others are concerned.

By the physics of scriptwriting he ends up on an asteroid, which is sometimes called a planet. Confusing, no? Confusing, yes! He collapses in despair after reading the rest of script. Urgh. Then the leprechauns appear. Is this Ireland? They certainly are little people.

The Lilliputians are led by Nebraska’s own Anthony Dexter, on whom more in a moment. Rather than stake Steve to the ground like a beached Gulliver, Dex has a better idea. Open his face mask. They do. The catatonic, I think but with him it is hard to tell, Steve breathes the asteroid’s air. (Yes this weeny asteroid has an atmosphere in the script if not in physics.) This is the good scene. Steve shrinks inside the fringed pressure suit to Lilliputian-size. Every part of him shrinks. Get it? Now the whole of Steve is six inches. The fraternity brothers shrivelled.

Turns out the planet-asteroid is called Rayton, Rayon, Rheton, or something and flies around under the control the oldest alien seen in B-movie land, namely Francis X. Bushman, who is obviously reading lines from cue cards most of the time and still gives a better performance than the rest of them. This old stager was born in 1883. Driving an asteroid was a demotion for him because the year before he had been Secretary General of the International Space Order in ’12 to the Moon’ (1960), reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Earlier still in 1925 he had been Ben Hur and drove his own chariot. Experienced he is then at driving.

By the way, the controls are Tibetan rock crystals and X just waves his hands over them. This trope became a commonplace when theremin players were recruited as UFO pilots.

With X at the helm there are no worries.

With X at the helm there are no worries.

Steve wants to fill out his pressure suit again and go home. The Raytons are shy and do not want to become a tourist destination, so are reluctant to let him go. To show him hospitality a jury of six young women sentences him to stay. They do so in silence. See, shy. Then the Solar Panelists attack, led by Jaws in the strangest rubber duck suit yet seen outside a bathtub.

See.

See.

They fight it out. Fight. Fight. Fight.

Fighting back-to-back bonds Steve and Dex, who then shows Steve how to escape, full-sized and fully functional.

The end.

Dex is Nebraska’s own; he peaked as ‘Valentino’ (1951). His next lead was in ‘Fire Maidens from Outer Space’ (1956), reviewed elsewhere on this blog. Dex was also with X in ’12 to the Moon’ so they could reminiscence about that around the script-fire.

The fraternity brothers could detect no Cold War themes in this movie. If there was such a message they did not receive it. Situation normal.

Disclosure statement. I watched this ages ago and no write up followed because of the benumbed state that viewing produced in me. Now that I have been hardened by so much else, I watched it again, such is my dedication to bleaders.

* For years the syllabus in ‘Power’ had this entry: ‘Beyond Steve Canyon and Rambo: Histories of Militarized Masculinity’ by Cynthia Enloe. The reference here is to the comic book which became a television series in the 1950s.

‘The Thing’ (1951)

IMBd meta-data is runtime 1 hour and 27 speedy minutes, rated a measly 7.2 by 21,596 cinemitizens.

Verdict: Chapeaux!

At a remote scientific station above the Arctic Circle in Alaska a giant carrot appears with a taste for blood!

Here’s the set up. A NORAD airbase tracks an incoming craft that crashes near a polar science station. Since it is time for a supply run to the base, Captain Tobey and his crew are dispatched to deliver the goods and check the wreck. Simple. Ah huh! That’s what they think. (No one seems to think it could be a Russkie.)

After that leisurely start the pace increases. Finding skid marks on the ice, and a shadow under the ice, as if a hot object had slid along and then burned into the ice which then froze back over it, they fan out to measure its shape. It is one of the several brilliant moments in the film. As they shuffle around beating their arms to keep warm in the Arctic wind, they come to form a circle which no one notices since each is preoccupied with slippery footing and the biting cold, until…..

‘We found one,’ says one of the grunts in amazement. (You either get it, or you don’t.)

After some of this and that, they find an NBA body frozen in the ice and drag that sizeable block of ice back to the station for further examination. By now the weather, per script, has closed in and they are cut off from the outside world in the Science Station of Otranto.

The ice block thaws and a very hungry Marshall Dillon emerges to find a late lunch. Several huskies will do, one of which tears his arm off. No problem, he will just grow another one. Bullets have no effect.

The scientists examine the detached arm and conclude…. It is a carrot!

When Carrot Dillon runs out of dogs, the scientists are next in line. Gulp! This is some vegetarian.

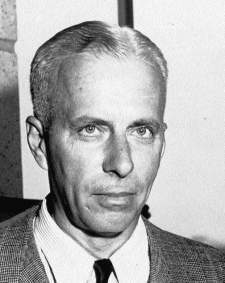

Howard Hawks wrote, directed, edited, and produced this masterpiece. The results is a B movie with A movie pizzazz. It has all the touches of this cinema doyen. Overlapping dialogue as two or three people talk at once. When Robert Altman did that in ‘Nashville’ (1975) he was hailed as a genius. Old news to cinemitizens. Role reversals when a woman takes charge of Captain Tobey. Inverted hierarchy when the best ideas come from subordinates.

Moreover, the soldiers act like scientists and the scientists act like soldiers. That is, the soldiers discuss the problem, test responses, revise, amend, try again, evaluate, and improvise. The scientists obey the senior man’s silly orders and he holds to his interpretation of the facts despite the evidence to the contrary.

The Captain’s authority lies in melding the men together, not in shouting out solutions or orders. The Senior Scientist, by contrast, gives only orders and silences other voices.

There are two women at the station and neither screams. One offers the first practical response to the Thing. How un1950s it all is.

Equally unusual is the presence at the station of Chinese cook who is later there at the denouement, cleaver in hand ready to fight this man-eating carrot. In most films of the day such a character would have been comic relief, i.e., stupidly stereotyped, and then forgotten.

Howard Hawks

Howard Hawks

Like Frank Capra, Hawks gives the supporting actors facetime and some of the best lines. It is a large ensemble cast of perhaps twenty and everyone of them has a line or two.

The conflict between the scientist and the soldiers is a trope in Sy Fy, but here, before it was done to death by later and lesser hands, it is fresh and vital. The scientist wants to keep Thing alive at all costs, including his own life. It is a being from another world. ‘We must communicate with it.’ ‘We must study it.’ ‘We must learn from it.’ He goes like it is the Second Coming. ‘What are a few human lives compared to the chance to learn from a creature of another world.’ Well….

To his credit, the Senior Scientist risks his own life to try to communicate with Thing, and in this the soldiers give him due acknowledgement for the courage of his convictions. Nicely done. No cardboard plot devices here.

By contrast the soldiers know an enemy when he attacks and respond in kind. It is a perfect contrast in almost every way to its 1951 cousin ‘The Day the Earth Stood Still’ where Klaatu came in peace. The Carrot from another world came for dinner!

At the end, the final words are a warning ‘to watch the skies’ because more may be on the way. Of course in 1951 Thing has to be a Red Thing. Hence, carrot.

It has been remade number of times but I have never bothered to watch the imitations. Though I note that Janne Wass of ‘Scifist’ writes that John Carpenter’s version ‘The Thing’ (1982) is one of the finest science fiction films ever made, and Janne is an oracle on these matters.

Wass and others go on about the Senior Scientist, with his double-breasted brass-buttoned blazer there in the Arctic hut, sporting a fur hat and a roll-neck cashmere turtle neck sweater. He has a goatee which suggests, to the rune-readers, that he is homosexual, a Russian spy, a villain, a male model, a…. Well he is the pole of an argument but as for the rest. No dice.

He presents his arguments and he lives up to them. In the end the soldiers pay him his due for that.

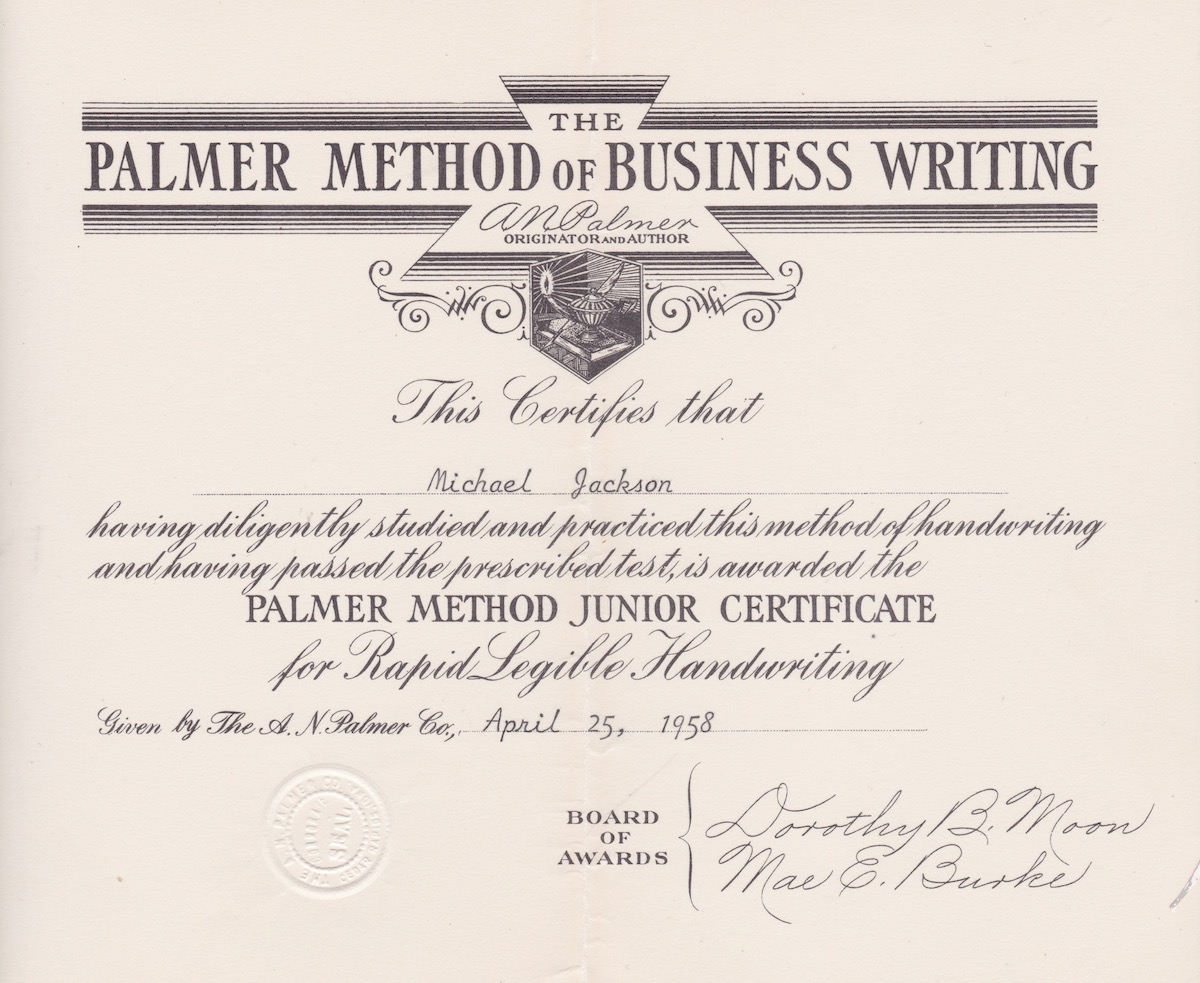

The Palmer Method lamented, but not forgotten.

From time to time some have said my handwriting was imperfect. Ha! To recognise perfection when seen is a lost art.

Below is documentary proof that I reached perfection in handwriting in an age when such things mattered.

The Palmer Method, despite vigorous opposition from the forces of darkness, supplanted the evil Spencerian Method with its serifs, whorls, flourishes, circles, and crosses. Those forces rebounded with the Zaner-Bloser Method, note that it took the combined efforts of two, to displace noble Palmer. Their triumph did not last long, as that method fell before the onslaught of the D’Nealian Method. No doubt prevailing today is the Twit Method suitable for Tweets.

In short, all has been chaos since Palmer was displaced.

Arthur Palmer (1860-1927) stripped pen(wo)manship of meaningless whorls and flourishes in the name of efficiency, hence the adjective ‘Business.’ (Although what customer of Telecom, Telstra is the cover name now used, Optus, or NAB would ever think efficiency had anything to do with business?)

Judging by the date, this certificate must have been at the conclusion of elementary (my dear Watson) school when I left the halls of Longfellow PS. The rigours of the examination have been blotted out of my memory.

The Hastings (NE) School Board in its wisdom named the elementary schools within its remit after poets and novelists, e.g., (Nathaniel) Hawthorne, (Henry Wadsworth) Longfellow, and (Louisa Mae) Alcott. There is also Morton school named for a less well known writer, Thomas Morton. Think what schools would be named after today? Shootings? Drug addled football players? Yak show hosts?

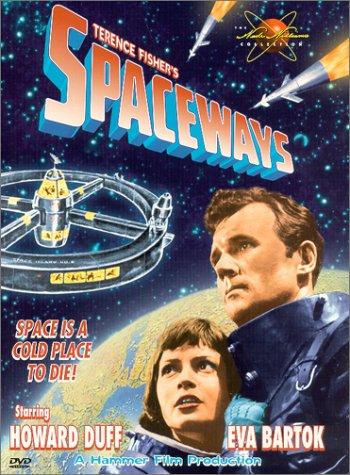

‘Spaceways’ (1953)

IMDb meta-data is runtime of 1 hour and 16 minutes, rated 5.0 by 307 cinemitizns.

Verdict: a snappy krimi with rockets’ red glare.

The space wheel shown on the lobby card is not even mentioned in this film.

The space wheel shown on the lobby card is not even mentioned in this film.

In the heart of darkest Devon a stereotypical assortment of 1950s Brits are playing with rockets. In their midst are an American stereotype and Hungarian Eva Bartok who together add international respectability to the Brit’s efforts to build and launch a spaceship. Sure, right. Britain as a world power. In 1953 England meat, sugar, bacon, chocolate, and much more were still rationed. But rockets needed no ration book.

We see models of multi-stage rockets and twice, in this short film, hear expositions of how they work. These lectures are interspersed with stock footage of the launch of single-stage rockets. Prof says we are about to launch a multi-stage rocket which works like this…. Then we cut to the launch of single stage rocket. This is the sort of continuity error that even the fraternity brothers notice, the second, or third time.

All the scientists and their families live in a fenced in compound with only two gates guarded by elite guards. No one can leave without the principal’s consent. No one can enter without a box of cookies. The place is tight, because it is super top hush secret. Los Alamos was like this in remote New Mexico.

Living cooped-up like this irritates the English wife of Mr American Stereotype so she, brazenly for the times, cuddles up to Dr Weasel. Meanwhile, Mr Stereotype sweats under the melting looks of that one-woman sauna Dr Eva. ‘An easy choice,’ shouted the fraternity brothers. But Stereotype is — briefly — full of scruples.

Then Wife and Weasel disappear from this top secret super hush impregnable establishment!

Yes, Erich, what other explanation could there be? Aliens abducted them! No, wait the limp-wristed investigator come from the Heap Big Smoke of London concludes Stereotype murdered Wife and Weasel.

So far so krimi.

But here is where we come back to the rockets. To get their corpora delicti off the secure, airtight base, reasons Limp Wrist, Stereotype put them in a test rocket which was then fired into the firmament where it will orbit for decades. If so, his guilt cannot be proven, but if the missing couple is not found elsewhere neither can his innocence be established. What a conundrum! What will happen! ‘Ho hum’ is what happened.

Without innocence he is not going to get Eva, so he is motivated to clear his name!

He climbs into a deep-sea diving suit and sets out on in the next rocket to retrieve the previous one and find out if any corpora are on it. Though quite why anyone on the ground would believe him is a scriptwriter’s secret.

Eva goes along for the ride, and she gets to deliver a noble speech about the need to conquer the stars.

Meanwhile, Limp Wrist has figured out that the missing two bribed an elite guard with a chocolate bar and vamoosed out the gate. They did so not for love, money, Superbowl tickets, or sex, but because Dr Weasel is an agent of Them. Wife traded Stereotype and the boring test site for a series of dank hotel rooms as Weasel eludes pursuit on his way East. Not what she had in mind. She gets even crankier when a life of eastern borscht appears on the menu. She squawks. To make it easier for Stereotype to end up with Eva, Weasel divorces Wife with a revolver, just as Limpy breaks in.

Question, why did Weasel bother with her in the first place? Answer, it is in the script.

Why is it called ‘Spaceways?’ The term is never used in the film during my consciousness.

Stereotype is now free of both Wife and suspicion and he and Eva can….. One of Stereotype’s biggest roles was once as Mr Adam(s). Get it.

Howard Duff is Stereotype and the word on the Wikipedia Street is that he was a man’s man, that means in this case, he was a repeated beater-upper of women. ‘Repeated’ because the Hollywood police were always sure the women provoked him. So no jail time. Drunk driving in the Hollywood Hills got jail time in those days — ask John Agar — but not aggravated assault. Ah the good old days.

This was a quota quickie from the early days of Hammer Films before it started to concentrate on Horror. It was distributed in the USA by Lippart, a bottom feeder. Quota Quickies for those who missed the earlier explanation were made in England to meet the legislated requirement of local content. Since the British Film industry was at full bore it could not meet the demand for 25% local content, it subcontracted much of the work to American shelf companies set up in England to meet that need. Ergo while the purpose of the legislative requirement was to promote British films, it had the opposite effect. A nice example of the backfire of a public policy. American investors in these quota quickies usually required an American actor in a leading role so that the films could be packaged for Yankee release.

Éva Márta Szőke Ivanovics’s backstory is more gripping than any role she ever played. Born in Hungary, at age fifteen she married a Nazi officer to shield her Jewish father. Later she married again to escape Communist Hungary and made it to Great Britain, where more marriages awaited. This from Wikipedia where it is said that she was a woman’s woman, i.e., did not suffer fools gladly. No wonder her career did not prosper.