IMDb meta-data is 1 hour and 22 minutes of treacle time, rated 5.6 by 4432 cinemitizens.

Verdict: A major disappointment.

While ‘The Creature from the Black Lagoon’ (1954) had atmosphere, tension, humour, likeable characters, elegant photography, and — most of all— humanity. This sequel from much the same production crew has few, if any, of those qualities. While it still shows some of touches of director Jack Arnold, they are bleached by the inept screenplay.

Some films can be saved by the actors but not in this case. This was the first of fifty B movie creature features/Sy Fy movies that would largely constitute John Agar’s subsequent career. At this stage he was still trying to be an A picture leading man, and not yet sleepwalking in his trademark catatonic style developed later. He is really trying, and very annoying, and so superficial that the fraternity brothers rooted for the Creature.

Not even a pay-check, a director, a screen-play, and a career motivated the ichthyologist to warm to Agar. No rapport puts it mildly. While required to embrace and kiss him, the viewer can see the icicles.

While dead at the end of the marvellous ‘The Creature from the Black Lagoon’ in the previous year, by the miracle of modern medical screenplay writing the Creature is restored to life in the Black Lagoon. The first fifteen minutes consists of his capture. Nestor Pavia, the only hold over from the original, captains the boat with his usual panache.

While Richards Carlson and Denning could not quell the Creature in the original, Bozos One and Two dynamite the lagoon on the assumption either they will kill Creature and take him back for dissection, or knock him unconscious so they can send him home for torture.

This approach alone indicates the Channel 7Mate intellectual level of what follows. Kaboom!

Once captured Creature is put on display for gawkers at Ocean Harbor in sun-bright Florida. There Agar and Ichthie torture him with food and cattle prods. Yep. Several times. Repeatedly. Their aim is to teach him to stop on the word ‘Stop.’ High level science it is. The fraternity brothers called the SPCA.

Ichthie and Agar exchange frozen lips now and then. The fraternity brothers know those kisses for the brush-off they are.

Creature has enough of their prodding and does some of his own. He kills Bozo One in the melée and escapes with ease since no precautions were taken, per the screenplay.

Though Bozo One was well known to both Agar and Ichthie neither misses a beat at his death. Just as neither gives a thought to Creature’s plight at the end of the cattle prod. (Yes, I know, Ichthie once says ‘she almost feels sorry for him.’ Put the emphasis on ‘almost.’ That means she does not feel sorry for him.)

(The next time cattle prods were on screen they were used by Bull Connor’s police in Birmingham on protestors.)

The opportunities lost were many. One of the strengths of the original was the underwater photography and the swimming of the stuntman, Ricou Browning, who is also in this one. There is some imitation of the original and Arnold’s touch shows in it, but it is not integrated into the insipid story. Moreover, once in Florida’s glare the mystery of the Black Lagoon is gone. There is another Arnold-moment when the peeping and stalking Creature is transfixed by the sight of Ichthie in her boudoir. But again it is cut before it sinks in.

In the aquarium there are some nicely framed shots from the water into the viewing area and the reverse that could have used for communion if not communication between the two worlds, but not so. The potential is palpable, but left at as a showy camera shot, not integrated into the story.

The Wiki word is that despite the commercial success of the original, the studio cut the budget for this reprise to the bone, because of losses on other pictures. The McKinsey managers’ assumption was, as is often the case and often right, the audience would be too stupid to notice. Considering the undeserved high score on the IMDb maybe they were right in the long run.

Whereas in the original the deaths of associates were shocking and disturbing, in this one it is not even clear to this inattentive viewer, ahem, if Agar and Ichthie realise Bozo was torn apart. Instead they go out on a dinner-dance date. Indeed they show no interest in the escaped Creature and feel no responsibility for anything. ‘Don’t blame them; they written that way.’

Now the Creature has no trouble spotting Ichthie and puts his moves on her. The de rigueur scene of the Creature Feature lobby card occurs as he carries her off into the night. Where promptly he puts her down. Must be heavier than she looks.

In the end Creature obeys Agar’s command to stop, so that the assembled NRA members can shoot him down. Another triumph for US foreign policy. See something foreign, shoot it.

The end.

Maybe Creature is the only sympathetic character in this soup because he does not have to speak any of the tepid and dreary lines of the screenplay. Silent and brooding with such underwater grace and agility, he embodies a personality none of the dry players can match.

A recurrent theme in Jack Arnold’s movies is the situation of women professionals, career and family. It is here in some dialogue but so poorly executed one suspects Arnold inserted it and the screen writer made no effort to integrate it. Still Ichthie does muse on her choice as a career woman and where will it lead, when most of her gal pals are now married with children. Agar ignores these concerns, per the mores of the time.

Perhaps the only thing that makes the movie worth watching for anyone who is not a copper-bottomed Sy Fyian is that it is Clint Eastwood’s film debut. He has thirty-seconds as a lab technician in the early going.

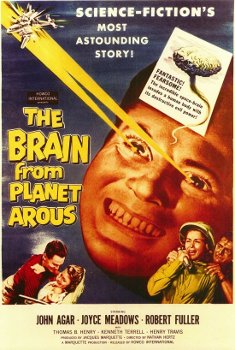

‘The Brain from Planet Arous’ (1957)

Internet Movie Database meta-data is 1 hour and 11 minutes of Dali time, rated 5.3 by 1161 cinemitizens

Verdict: Pop goes the balloon!

John Agar becomes the helpless victim of….a brain. It was a new experience in his long downward descending film career.

Gor from the Planet Arous is on the interstellar lam from the laws of physics, pursued by agent Vor. Gor is a balloon on a string painted with a human brain. One prop does them both since all Arousians look alike to the fraternity brothers.

Atomic energy testing on Earth attracted Gor who wants to use it to return to Arous and take revenge!

So far it sounds better than it is.

Los Alamos and its cottonwood trees are nearby and so is the crack [gasp] nuclear physicist Agar whose expertise runs to reading voltmeters. He is not employed on the bomb testing project but is yet a nuclear physicist, freelance it seems, just hanging around. The fraternity brothers scoffed since there was not a slide rule was in sight. Strike one. At no time does he intone E = (MC)2 or any other incantation of the high priests of science. Strike two. Nor does he sport a nerdy white pocket protector. Strike three. Yer out!

Gor merges with Agar. Read that again slowly. Gor merges with Agar… who then goes all Lee Strassberg, writhing, sweating, doubling up, twisting, pounding his head against a wall, like a Red Sox fan re-acting to another drubbing by the Yankees. There is one marvellous scene where he stoops over a water cooler and is photographed through the water in the tank in a weird and disturbing image.

What it shows is a big fat head. Nice but not integrated into the film.

Warning, danger ahead! When possessed by Gor, Agar tries to act. His evil laugh is as good as Bart Simpson’s but no better. Passable for a ‘C+.’ He gloats at his enormous power over savage Earthlings, while telling himself that Sally will do nicely. A ‘D’ for gloating. He then dons reflective contact lens and wills destruction. This is definitely an ‘A+.’ Overall as a villain a ‘B-’ average.

Since he is not employed, Agar has plenty of time to roam around and frequently visits his girlfriend Sally who lives with her dad (Thomas Browne Henry, a stalwart of 1950s and 1960s television, who is picture above near the water cooler) with the faithful hound, George. (Who but a scriptwriter would name a dog George?) Of Mom we hear not a word.

When Agar tries to act, Sally and Dad notice a change. In one notable scene Gor-Agar tries to rip her clothes off. The fraternity brothers had pretty terse criticisms of his technique. Needing the pay check for completing the role, Sally perseveres with Agar.

The balloon plays a dual role, both Gor and Vor.

The balloon plays a dual role, both Gor and Vor.

She and Dad find the cave of the ‘Robot Monster’ (1953), a film reviewed elsewhere on this blog, which also has some clothes tearing in it, where Gor hangs out. There Vor appears with the same voice but in a reassuring tone, like Richard Boone trying to be nice. He clues them in on the plot and reveals Gor’s Achilles Brain heel.

Between bouts of gloating, triggering nuclear explosions, twice blowing Malaysian passenger planes out of the sky, declaring his lust for Sally, Gor-Agar complains of terrible headaches while clutching his stomach. The director skipped anatomy classes in college. There is more which the reader is to be spared.

Vor decides to inhabit George to keep track of Gor-Agar because at times Gor must leave Agar’s body to update the IOS and Gor is vulnerable at that time. Vor will pounce on Gor then! This is an intriguing possibility balloon-à-balloon, and maybe some dog stunts to equal to Agar’s gut clutching, but no. George rides around in the car a couple of times and goes to sleep. Another method actor: realism. Pouncing is out.

In the end — a long time in coming — Sally gives Agar written instructions with a drawing as explained to her by Vor, and leaves an axe handy for him to use to split the atoms in Gor’s balloon brain. Which he does.

When he recovers himself, i.e., leaden and bored, Agar asks her how she knew where he should strike per the instructions and with what, namely the axe. She tells him about Vor.

He dismisses this explanation as her imagination! She exits to collect the pay cheque.

The end.

Ah the 1950s when chauvinism, sexism, whitebread, and stupidly were the coin of the realm. But wait, has anything changed?

Rumor has it that some screenings were interrupted by the announcement of the Sputnik success.

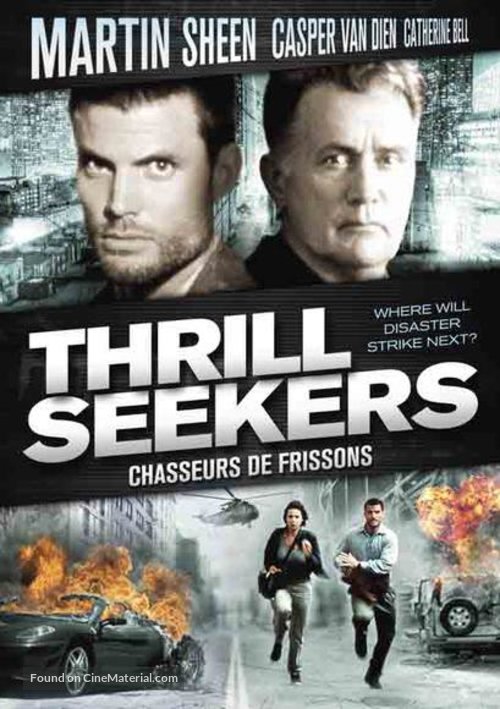

‘The Time Shifters’ or ‘The Thrill Seekers’ (1999)

1 hour and 28 minutes of treacle time, rated a vastly inflated 6.0 by 2246 of the producer’s extended family members.

Verdict: Viewer beware. I could not finish this one. Not even Lieutenant Willard’s name in the cast list could keep me at it.

The premise is a good one and offers much potential which was not grasped by writer, director, producer, or the cast.

The premise is that in the future backward time travel is possible, and it has become disaster tourism. Those in future travel back in time to take part in disasters, to be rescued in the nick of time by the time travel agent. Sail on the Titanic. Be a Red Sox fan. Land at Omaha Beach. Board the Hindenburg. Vote for the Twit-in-chief. And be home and dry by dinner time, spared all consequences for these and other disasters.

Such time travellers are discovered in this story by a lazy and incompetent journalist with a reptilian sneer who can barely drink instant coffee. Maybe that is why I could not warm to the movie. Where is the comatose John Agar when we need him?

The proposition that Casper the Ghost might have the presence of mind, energy, wit, intelligence, and insight to figure this out in five minutes was just too much for my suspended disbelief.

Those IMDb users who made comments concentrate on the story’s potential, not the execution of the material. Not even the fraternity brothers could warm to this.

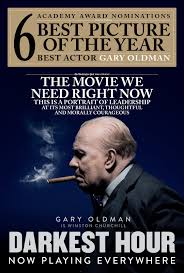

‘Darkest Hour’ (2017)

Replete with inaccuracies and fabrications yet ponderously and pretentiously presented as though a documentary. ‘History on Film’ I hope will demolish it in due course. Until then I offer my comments.

Because the gullible cinemitizens of IMDb will eat it up and think they now know the history it has to be nailed.

They rate it 7.4 from 94,328 votes and it runs two hours and five minutes. Its documentary approach goes day-by-day in May 1940 as Churchill took office, but it inserts events that occurred later in June in this May narration. It attributes to Clement Attlee, the Labour Leader, a position he never took. It trivialises the ‘V’ sign. It fabricates a Tube ride. It shows in May 1940 an American aircraft only manufactured in 1943. Ditto the automobiles. It garbles Churchill’s several meetings with Paul Reynaud who did want to fight on.

In short, despite the pretension of accuracy implied by the documentary approach, it is as careless with fake facts as the Twit-in-Chief.

It adds nothing to our knowledge of the Fox, Edward Halifax, nor does it explain the transformation of King George. These two figures are very well drawn by the actors, respectively, Stephen Dillane and Ben Mendelshon. Halifax remains a man of mystery. He was everyone’s obvious first choice as PM who stepped back and back. King George surprised Churchill by his conversion to the ‘fight ‘em on the beaches’ attitude by learning together with his wife to shoot a pistol.

Nor does the film credit Churchill’s long acquired mastery of parliamentary forms, rules, and conventions which he used to gain and keep support. The grand strategy was in his speeches; the killer tactics were in meeting schedules, ordering of items on an agenda, orchestrating other speakers, and so on.

Attlee had said repeatedly in public and private that he would continue to serve in War Cabinet regardless of whom the Conservative majority installed as PM. He did not make his service, and hence national unity, conditional on Churchill’s selection. It is unthinkable that he would have done so and he did not.

Though every detail of this time is well documented, the facts are not enough for the film-makers.

Having seen Churchill enacted so many times (Albert Finney, Robert Hardy, Timothy West, Brian Cox, Timothy Spall), it is impossible to see him with a fresh eye. Having said that, Gary Oldman seems to have compiled a host of external mannerism and ticks without any inward unity. The declamations, the cigars, the shuffling steps, the staring eyes, are all there without anything inside rather like an animation from Madame Tussaud’s wax work collection. The publicity hype says he studied many films of Churchill. No doubt. He has the walk; he has the talk, but he has no empathy for the man inside.

Disclosure statement. By some combination of button pushing I watched this in a French dubbed version on a trans-oceanic flight. I had not intended to do that but once it started I let it run as my French lesson of the day.

‘Zombie Cats from Mars’ (2015)

IMDb data: 1 hour and 37 minutes, rated 3.5 by 64 cinemitizens.

Just as some suspected for eons, cats are the devil’s familiars. Two high school boys see a UFO at twilight, but say to themselves, despite the evidence of their eyes, that it is but a weather balloon and that explains why weather predictions are so accurate. The irony detector went off.

Of course, they are ridiculed for seeing a UFO, though they did not say that they did. The small town bully gets to work per the script. Down the street is a cat lady with fifty or more felines. When the Martian cat shows up, she takes it in. That was her last mistake.

The Martian has glowing eyes which are soon imparted to its kind. They turn on the cat lady. Who is going to clean that up? This is just the beginning. Down they go like mice before the grim cat reapers.

The police are inept and the narcissistic carrion of the media find the string of murders amusing, but boring after a time. Everyone in the small town is killed, one-by-one, until our protagonist wakes up to find it all a dream for a short story he has to write for homework. The end.

The production values are Ed Wood standard. The players are…sincere. It does not take itself seriously and most is thus forgiven, though not all.

How we know the killer cat came from Mars is unknown. Where the UFO was parked is likewise unknown. Why did they come? Most important of all, what makes them zombies?

‘Journey to the Seventh Planet’ (1962)

IMDB meta-data is runtime 1 hour and 17 minutes, rated 4.8 by 1243 cinemitizens.

Verdict: Stay at home.

In 2001 all problems have been solved on Earth. Pi has been calculated to the end. The drains at Wrigley Field have been cleared. The United Nations (having exterminated the John Birchers [Hooray!]) governs one and all in peace and prosperity with plenty and no conflicts among humanity. At long last we have learned to live together in harmony.

Well, it is fiction.

Note that the initial stock footage of space flight is replete with uniforms of the USA and USAF. No UN blue in sight.

The opening narration continues, the inner planets, including Saturn, have been explored to ensure that they are Trump-free. In order to be sure that the whole Solar System is free of this deadly menace, a doughty crew of five, including the ubiquitous John Agar, sets sail for Uranus, the seventh planet to give it the once over. From here on this is one for the fraternity brothers: inane, puerile, salacious, and other words beyond their vocabulary.

The betting opened on how many of the five would make the return trip. The crew is multi-national with one who goes on about Leprechauns, another who waxes on about Danish windmills, a third who has the wooden heart Elvis sang about, and a vaguely other, along with Agar. All white-bread.

As they approach Uranus, they read from the array of voltmeters on the cardboard flight deck that the ground radiation is Chernobyl, that the ambient temperature is -270 Kelvin (or Fred), that the atmosphere is a noxious brew of Pat Robertson-speak, but they land anyway. Of the crushing gravity, not a word is said. Brave men, these.

Now they take readings again. ‘Huh!’ John Agar can deliver that line like no other, as he sleepwalks toward another pay cheque. It is +72F; it is mild; it is radiation free; it is …(too good to be true but spacemen were not selected for brainpower). Donning coveralls with a UN patch, crash helmets, and grasping caulking guns they go forth with scuba gear on their backs. They are ready for anything. Anything, except what they find!

They find a sylvan glade wherein all their individual wet dreams come to life. Sort of. Beautiful women from the past of each appears to them individually. Hmm.

The fraternity brothers sat up at this point, and stayed up.

The fraternity brothers sat up at this point, and stayed up.

After….hmm… a while the spaceboys figure out that these women cannot be real. The fraternity brothers wanted to know…. (how they knew.) Conclusion? An alien intelligence is dredging these images up from their minds and projecting them. This manipulation cannot be tolerated, though two of crew demur, claiming that a good manipulation is just what they need after all that script time in space.

Nonetheless, they set out to find, confront, and destroy this intelligence. US foreign policy Prime Directive number one: seek and destroy.

The baleful influence of Neo-Cons extends to Uranus. The white rat is hiding in plain sight.

The baleful influence of Neo-Cons extends to Uranus. The white rat is hiding in plain sight.

Meanwhile, between alien-destroying bouts, they cavort with the women. The fraternity brothers object to the word ‘cavort’ since all they do is talk and there is one chaste embrace. ‘Cavorting,’ they cried, ‘is what we major in and this is not it!’ Point conceded.

Evidently the space invaders prevail but one of them gets absorbed, and not in a book.

The Danish captain insists on taking along his dream squeeze as they flee the planet before the requisite KABOOM. Agar does try to tell him she is not real, but…. A man has got to do what his first friend tells him to do. She disappears in the mist, after being rescued. Some gratitude that!

That is one version of the events. Here is the revisionist history now taught in Uranian universities.

Invaders land without permission. They come in battle dress and armed with fearful caulking guns. To make them feel welcome Brain conjures their wettest dreams, which they enjoy to the limits of 1962 film censorship. No harm comes to them.

In response, they set out to destroy Brain. To survive Brain must take defensive action, and it dredges up from each them nightmares to inhibit their destructive actions.

Put that shoe on!

This is a product of Sid Pink and Ib Melchior. That says it all.

It opens and closes with a mournful ballad about the ‘Journey to the Seventh Planet.’ That alone was worse than the film, albeit shorter.

Though Denmark is much mentioned, it was filmed in Sweden and all the actors, including the Irishman, have Swedish names, apart from Agar, in the credits. Maybe Agar is a Swedish name? No one speaks with a Swedish accent, so maybe it was dubbed. Hard to tell on the print I watched from Daily Motion.

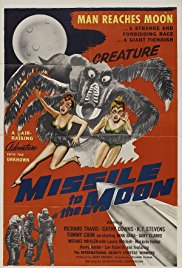

‘Missile to the Moon’ (1958)

IMDb meta-data is 1 hour and 19 minutes and rate 3.6 by 732 cinemitizens.

Verdict: The first astronaut was a Moonie!

It bears an uncanny resemblance to ‘Cat-Women of the Moon’ (1953), reviewed elsewhere on this blog, but there is less dancing and this time no one smokes on the Moon, these being the high points of the film. Yet it does have some interesting features which go undeveloped in the screenplay in favour of the spacers old friend, the meteor shower.

With their own money Dork and Steve have laboriously built the cardboard cut-out of a spaceship in the backyard and are about to blast off for the Moon when, the heavy hand of officialdom falls. ‘Private enterprise shall not go the moon,’ says a man in an Army Navy Store uniform. The Air Force is here to confiscate your rocket which will fold down nicely into a briefcase.

Steve rolls with this punch but Dork is infuriated and becomes driven to set off on his own. There are close ups of Dork fuming. [Censored.]

The rocket is surrounded by an electric fence, yet two reform school drop outs get inside without breaking a fingernail. See, the cut-off switch for the fence was conveniently located by the gate and it took only a dime to pry it open and kill the juice. A dime is all the sense these two elderly teenagers had together but it was enough. They hide in the rocket. Well, they stand around in the rocket’s ballroom and Dork finds them but keeps it a secret in return for their cooperation in his flight to the Moon. ‘Sure, why not. It is a little out of the way but, hey, it’s a free joy ride.’ This is delinquent logic at work.

While Dork and his cronies are dialing dials, unbeknown to them, Steve and Squeeze come on board for reasons known only to the scriptwriter.

The original plan was a crew of two, now there are five on board. Yet somehow the cardboard cutout rocket is up to it and they have lift-off.

In flight Dork snuffs it when the BO of the felons hits him in the enclosed cabin. Well, he hit his head when he slipped in the meteor shower where he went to escape the aforementioned pox. As he dies, he tells Steve that all is programmed and it must be followed exactly. He goes on about ‘my Lido,’ as it pining for Venice. Was he in the wrong movie? Good question.

Cutting to the lunar landing, they discover the two-crew rocketship has spacesuits for four, though the suits do not extend to the back of their necks. They are in for some Moon tan. They encounter some of the slowest moving stuntmen in the geriatric wing of the old actors’ home decked out as Moon Rockmen. Squeeze falls down in front of these Rockers and is unable to get up in the Moon’s low gravity so she waits patiently for rescue by Steve. She stave off the Rockers by reciting Zeno’s paradox. What other explanation could there be, Erich? Note that the Moonscape had scrub bush on it just like that in Bronson Canyon. What an odd coincidence. They shelter in a cob-webbed cave where they find: spiders, torches, oxygen, beauty queens, and the Lido. But no cat women.

Turns out Dork was a Moonie! His plan was to go to Earth, build a rocket ship and return to the Moon by missile. Neat so far? Then the beauty queens would pile into the rocket and return to Earth to…. Now how Dork got from the Moon to Earth without a rocket in the first place is left to mystery. The BQs have to leave Moon because the oxygen is running out, though where it ever came from is left to mystery. There is mystery in this screenplay.

The idea that the first Earthmen in space is a Moonie, well, that is a twist, and that lust for The Lido is his fuel might add to the fun, but it does not because there is no fun to which to add anything.

Along the way the enlarged spider appears to justify the lobby card. One of the delinquents fries. (See comment above about neck exposure.) Various BQs come to bad ends.

Oh, and we discover that ‘The Lido’ is the maximum BQ.

Notice the boss headwear.

Notice the boss headwear.

She mistakes Steve for Dork, such is her undying love for Dork, because she is blind, because Steve is wearing a medallion Dork gave him with his dying breadth, because the scriptwriter hit the wrong keys. She wants a (re)union with Steve the ersatz Dork, and this riles Squeeze to something more than the mild boredom which has been her contribution to the dramatic arts so far.

‘Cat-Women of the Moon’ has the same IMDb score of 3.6 but has more exposition of the Moonies that strives for plausibility, and fails. Moreover, it had Marie Windsor to add some spunk to proceedings and some old hands in the crew to deliver their lines with conviction, rather than this weary and dreary crew. No doubt the two delinquents were there to capture the Steve McQueen youth market per ‘The Blob’ (1958). Fail!

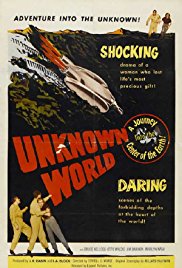

‘Unknown World’ (1951)

IMDb metadata is 1 hour and 14 minutes of Dali time, rated 3.9 by 731 cinemitizens.

Verdict: Stay home.

Enrico Fermi frightened a generation of school children with the prediction that nuclear explosions would ignite the atmosphere and incinerate the Earth. This film starts with that assumption.

A team of scientists decides that to survive humanity must burrow into the Earth. Mole-ville here they come. This is a private enterprise, and though it attracts much press coverage, it is underfunded. Most of the ink is derogatory as the Fourth Estate once again meets the standard of irresponsible journalism.

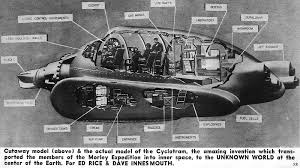

However the hoo-hah attracts a wealthy layabout with a big smile who puts up the money provided he can go along for the ride. While all other members of the crew are doctored scientists, he is a golden brick. Tensions surface but taking him is the only way to proceed. All aboard the Cyclotram (which has since been used to drill subway tunnels in Athens, Istanbul, and London).

We see schematics. We see dials. Levers. Switches. Gizmos. Instruments. What is worse is that there are expositions.

We get excerpts from doomsday lectures to thousands who — contrary to the natural law of the lecture theatre — seemed awake.

We get bored stiff. The players are earnest and it is presented with urgency, but none of it is engaging.

The team consists of a small group of fifty year old, near-sighted, round shouldered, shuffling PhDs, and one virile ex-Marine engineer, who is there to fight with the Gold Brick over the attentions of the one female in the crew who is much younger than the other PhDs. She is the nutritionist who has made the dietary pills off which they will live as they bore and bore and bore. ‘Boring!’ cried the fraternity brothers.

Is the aim to find the underground cavern of Edward Lytton Bulwer’s Vril (‘The Coming Race’ [1871]) where humanity can become Moles. Or is the goal to rescue John Agar from “The Mole People’ (1956), reviewed elsewhere on this blog? If the latter, forget it.

They enter the underworld by sailing to Carlsbad Caverns and descending into a dormant volcano. First up then down, down, down. What could go wrong? Ever try sailing to New Mexico?

At least they are safe from the Sy Fy scriptwriters nemesis, the meteor. But things do go wrong. The Gold Brick is annoyingly supercilious and careless. There are speeches about bending nature to human will. ‘As if,’ said Georg Hegel.

But then….poison gas, volcanic eruptions, dandruff, contaminated water, and annoying remarks bedevil progress.

Some of the doctors croak and the Gold Brick matures. His growth was well done, and of course the lady doctor warms to him now that the ex-Marine is toast. Gold Brick is the only one under fifty left anyway.

They go down, down, down. Much to the disappointment of the marketing department they find not a single enlarged lizard creature to grab the doll for a picture on a lobby card. No stunt men in rubber suits were in the budget. Instead there is an oppressive journey into darkness. In fact, it is much closer to the text of Jules Verne’s ‘Journey to the Centre of the Earth’ (1864) than the big budget version of it in 1959 with that toothy crooner in it. Not reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

Spoiler ahead.

Moreover, it is resolutely downbeat. Nothing good happens. ‘Yawn,’ agreed the fraternity brothers. They — the players not the brothers — are submerged in an ocean 2500 miles underground! Not good. Doomed. But then the scriptwriter reached for an up-current and it propels the craft to the surface (stock footage of Pismo Beach follows) and they are saved. Delighted to be back where they started from, they throw open the hatch.

What was that about decompression? The End.

All of that and they are back on top where Fermi’s burning atmosphere awaits them. Huh?

The production teams includes veterans of many of Sy Fy films who really should have known better.

‘Mission Mars’ (1968)

The IMDb metadata is 1 hour and 35 minutes run time, rated 4.7 by scant 200 cinemitizens.

Verdict: Not even Carl Kolchak could save this one.

Three American astronauts blast-off for the Red Planet (quite visible of late), but before that about twenty minutes is devoted to their wives and girlfriends telling them each to be careful. Nearly the same dialogue is repeated three times by the women. That astronauts have lives and cares is certainly worth screen time but the repetition makes it irritating rather than engaging. Each of the women give it their best shot. The problem is not the singers but the song.

The flyboys blast-off and the early going has some verisimilitude, though the shots slide between a Jupiter and Atlas rockets in NASA stock footage of Florida launches. The fraternity brothers are up on rockets and spotted this gaffe. Our heroes encounter the usual screenwriting tropes of communication blackouts, meteor showers, and body odour. Darren McGavin and Nick Adams do their best to make it credible.

There is also an amusing moment when McGavin and the third member of the crew, who the fraternity brothers immediately identified as a dispensable Red Shirt, tuck into a meal of pellets and brine, while Adams produces from his kit a salami sandwich and thermos of coffee. They are appalled, aghast, and envious all at once. One of the few nice touches in this turgid celluloid.

Nearing Mars, they pass, floating in the void of space, two dead spacesuited Soviet cosmonauts. Gulp! That gives them pause for thought about a fate that might await them in the screenplay. This encounter ties up an earlier aside about Soviet interest in Mars. So far, so usual.

In the approach for landing they take actions that separate them from the supply canister that was to accompany their landing. ‘We’ll find it later,’ says McGavin. We know what that means. Trouble.

They land and alight with no ceremony or awe. Just a remark to the effect that ‘So this is Mars.’ They spend hours, well so it seemed, pumping up weather balloons for scientific reasons unknown. To find the supply pod they scout around. Yep. While they have on white overalls, their face masks came from a hockey team and do not seal into the overalls.

Soon enough the local flora and fauna objects to their presence: Terra Nullius or not. The Red Shirt in the crew of three is gobbled up by a large golf ball.

This orb looks very much like the enlargement John Carradine used in ‘The Cosmic Man’ (1959), reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

This orb looks very much like the enlargement John Carradine used in ‘The Cosmic Man’ (1959), reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

They find a third Soviet cosmonaut frozen in a spacesuit. ‘We can’t leave him here,’ McGavin says. (He gets all the good lines.) Gamely Nick Adams carries the frozen Soviet block of ice back to the ship. The fraternity brothers were pretty sure leaving the Red there was just fine, and how could little Nick carry that big Slav with all his gear to the ship anyway. That attitude just proves why they will never graduate from scriptwriting school.

The bug-eyed saplings and gigantic tin foil wrapped golf ball cripple the ship making departure impossible. Stop there and check the Vulcan logic.

The FF (flora or fauna, the fraternity brothers could not tell which was which and neither could the special effects department) wants the strangers gone. How to do that? Disable the ship so they have to stay. Check. That is scriptwriting school logic, Mr Spock. It is to be seen in countless other Sy FY features like ‘Forbidden Planet’ (1956), reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

The Siberian thaws out and comes to life while Nick goes to tee-off on the golf ball, nine iron in hand. Bad move. That Reynolds Wrap tin foil is club-proof. Gobble. Gobble.

However, while the golf ball is masticating Nick, McGavin sees his chance to blast off and puts the Siberian at a console to twist dials. Dials twisted. Kaboom. They take off in joint American-Soviet effort at escape. For the time that is a concession to the unity of mankind in the face of mean plants.

The end. Well, I stopped watching, ahem, maybe earlier, too.

The story and production come straight from a 1950s B movie, yet it was released in the same year as ‘Space Odyssey 2001.’ It seems all the more dated when one realises that in less than a year the audience would see on the television news a man walking on the Moon.

The early going and the end are marred by an insipid soundtrack that has no connection to either the form or content of the movie. The producer must have had an aspiring musician in the extended family.

It was made in Miami and the supporting actors in the cast were evidently local talent, not the familiars of Hollywood. That does give it a freshness but it is soon lost in the early repetitions.

This same director’s oeuvre includes ‘Santa Claus Conquers the Martians’ (1964), not reviewed on this blog, yet. But only because I have been unable to locate it online.

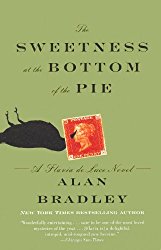

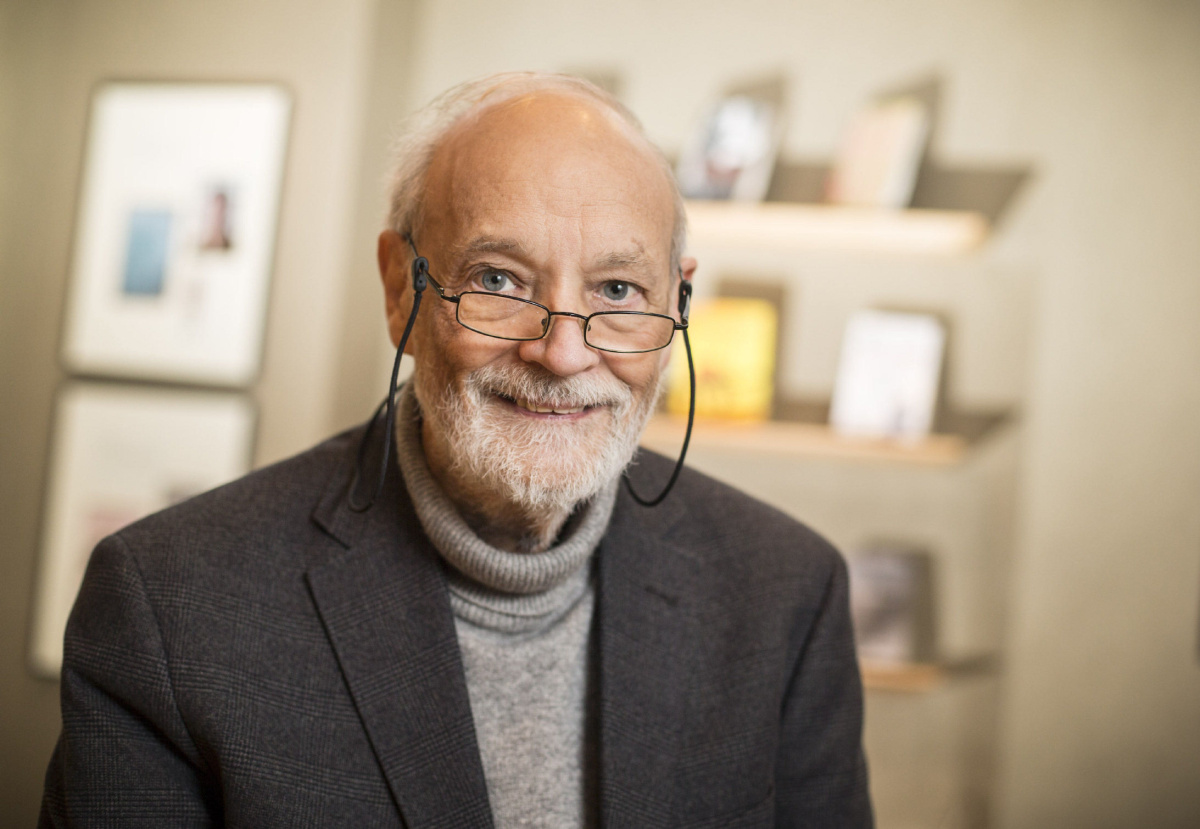

‘The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie’ (2010) by Alan Bradley

This is the first in a series of nine book-length titles (and one short story) recounting the many adventures of Flavia de Luce, aged eleven and a half, in Bishop’s Lacey of rural England of 1950-1951. ‘Flavia’ is pronounced, she has more than one occasion to say, to rhyme with bravia as in bravo.

With pigtails flying, aside her faithful bicycle Gladys, Flavia goes where no plod ventures, under beds, into holes in the ground, inside ovens, over roof tops, through holes in the wall, diving in to muddy ponds, all the while musing on the wonders of chemistry.

It all began early one morning, very early, about 4 am, while she was waiting for an experiment to mature, Flavia discovers in the cucumber patch a dying man. ‘How interesting!’ is her reaction, as he breathes his last.

When plod, duly summoned, shows little interest in her or her observations (which are many) she resolves to get to the bottom of things before plod does. The race is on, but only one of the runners knows it: Flavia.

First stop, the local library, then the local gossips, as she mobilises village resources to identify the deceased and infer his purpose then to find his killer while plod follows police procedure, i.e., drinks tea, calls London, fills in forms, drinks tea, scratches ear, fills up tank of police car with petrol, rests, and goes home.

The cast of characters includes a largely silent Father, who occupies himself most hours behind closed doors with stamp albums. There is a bounded retainer, Dogger, whose emotional frailty is debilitating. Father and Dogger spent long years in Japanese prison camps, and in different ways have never recovered from it. Harriet, wife and mother, died just before the war, leaving a very large gap. Though gone for a decade she remains a presence in Buckshaw, the decaying family pile. At the mere mention of Harriet’s name, Father faints. Meanwhile, Dogger cowers in the greenhouse with his demons. Mrs Mullen does for them and provides a pipeline to the village and sanity.

Older sisters Ophelia, the narcissistic musician, and Daphne, the bespectacled reader, round out the ensemble cast. Rivalry among the three sisters has become Total Sibling War.

The Molochs of Inland Revenue undermine Buckshaw with questions, writs, and invoices. Harriet died without a will, leaving questions of property much vexed. Four years in a Japanese prison camp did not break Father, but Inland Revenue seems about to do so. He could satisfy these meat eaters by selling her jewels (valuable), books (rare), and automobile (handmade) but this he resolutely refuses to do, as if by keeping them he keeps her.

That Flavia is the very image of Harriet explains why Father can hardly look at her, though she does not understand this and feels slighted. Father and Harriet were cousin and he knew her at Flavia’s age.

I gulped down the nine books of the sequence, one-after-another, each a delight. Flavia does not always understand what she sees or hears or is said to her, and she makes mistakes. Nevertheless she has the optimism, audacity, energy, and determinism to overcome all obstacles, including those of her own making. When all else fails, when she is totally desperate, when there is no alternative, she will even tell the truth!

The plotting is neat, details play into the larger picture in due course. There are no superfluous asides and backstories. The characters are delightful, most of all the star of the show, Flavia, but also Dogger, Mrs Mullen, the Vicar, and the Weird Sisters, and more. While Flavia makes the snap judgements of youth, time and experience cause her to change her mind more than once. Call that growing up.

There is much chemistry. Like many a prepubescent girl, Flavia keeps scrap books. In her case they consist of newspaper and magazine cuttings of homicides by poisoning. She got kicked out of the Girl Guides when for a home science project she distilled arsenic from house cleaning products. On the wall of her room are autographed pictures of many chemists, particularly those whose work expanded knowledge of poisons. She has longterm plans for the Weird Sisters.

There are some false notes now and again, and the one book set in Canada at boarding school seemed somehow lesser, though it has some great moments, the whole is less than the sum of its parts.

Neither Amazon, Wikipedia, nor the author’s web page offers a simple chronological list of the titles in the series. Below is my effort to supply that list.

‘The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie’ (2009).

‘The Weed That Strings the Hangman’s Bag’ (2010).

‘A Red Herring Without Mustard’ (2011).

‘I Am Half-Sick of Shadows’ (2011).

‘Speaking from Among the Bones’ (2013).

‘The Dead in Their Vaulted Arches’ (2014).

‘The Curious Case of the Copper Corpse’ (2014) (a short story).

‘As Chimney Sweepers Come To Dust’ (2015).

‘Thrice the Brinded Cat Hath Mew’d’ (2016).

‘A Grave’s a Fine and Private Place’ (2018).

Alan Bradley. Chapeux!

Alan Bradley. Chapeux!

I first espied one of these titles (‘As Chimney Sweepers Come To Dust’) in the English-Language section of a bookstore in Helsinki in 2016 and when I got back to it, I found it had predecessors so I started with the first, reading on the Kindle, and the banquet began. Now sad to say I have read them all, but fear not for I have returned to this, volume one, and started over. ‘As Chimney Sweepers Come To Dust,’ by the way, was the one I saw in Helsinki and I am glad that I did not start there as I might have then stopped, this being the one set in Canada as referred to above.

Dare we readers hope Flavia will continue her chemical ways in adolescence and adulthood?