IMDb: 1 hour and 32 minutes of Dali time, rated 3.7 by 280 relatives of the actors.

A photographer and a model are in the English countryside doing a fashion shoot. Much snapping in a sunny lea occurs, then for a change of mood they enter a darkling glade, and after a few minutes there is off-camera heavy breathing. No, wait that was the fraternity brothers on the sofa.

Well, yes there is heavy breathing on the soundtrack, and we get a distant fisheye view, the first of many, of the twosome. They then feel creepy and scoot.

Back in his home dark room, the photographer develops the pictures and sees….! (Well, maybe it was David Hemmings from ‘Blow-up’ [1966] because it starts the same way). I was never quite sure what we were supposed to see in the photographs since they were out of focus as was most of the film, but latter it is declared that there were ETs on the snap. Ok, those with the script should know.

The snapper has a haircut like an unclipped Puli or maybe two Beatles’ wigs one atop the other. With that hair he cannot be too bright, and to prove the point in the dead of night he returns to the glade. Guess what happens to him!

Yep, the ETs get him, though not without a fight in which a local farmer and his dog are casualties. Thereafter the body count increases. Puli is on board the saucer and the twig-thin and short ETs in grey, polyester, and knit onesies with opaque blue visors set about him. These rompers are stompers!

Boy, can he bug his eye out! Boy he had reason to do so! See the size of that probe! Yikes!

Efforts to find a picture of the ET onesies failed. The conspiracy of silence applies even to that!

Puli had left a message for Eye Candy of his idiotic plan for a nocturnal visit to the glade and she turns, as one does, to the nearest blood sucker from the media, who sets about making matters worse.

Thereafter it is a race to see who can destroy the evidence of the ETs first, the ETs themselves with their fisheye views and heavy breathing, or the conflicting forces of order: police, detectives, military, secret service, and the men in black. Yes there three men in black and without the moral compass of a pug they go crazy. The forces of order want to suppress the ET news to avert panic and have been doing so for two generations. Well done, chaps. They spend a lot of time arguing among themselves about KPIs.

The ETs may have their own agenda but there is no communication with them. We are left to fear the worst, McKinsey managers! They just breathe and gander while themselves knocking off bystanders. The body count rises as both sides seek the pictures and then the negatives.

Spoiler alert!

It does have a twist in the tail. When Blood Sucker has the facts, the men in black, not wanting to be outdone on the KPI of bodycount, kill him and his two or three, I lost count, abettors along with Eye Candy in a hail of sound effects!

The end.

Moral? Do not cross men in black without a pug.

The closing title assures us that this story is based on fact. How so since most of the principals are dead is anyone’s guess? Did the the men in black kill-and-tell?

It is an Italian production set in England with German and American actors as well as Italians. While the number plates are English and there is Land Rover much in evidence neither this vehicle nor any of the others are left-hand drive. The American is dubbed with a Scots accent, sometimes. The German speaks German and is dubbed with a mumble.

Italians have been trying to pretend they do not have an ET problem by projecting such tales on to England, but Silvio has been a dead give-away.

‘The Wild Women of Wongo’ (1958)

From the IMDb: 1 hour and 12 minutes of Dali time, rated 2.1 by 912 cinemitizens.

Verdict: woeful.

In sum and in short, on the tropical island of Wongo, a tribe consisting of ugly men and of beautiful women discover that the nearby island of Goona is inhabited by a tribe of ugly women and handsome men. This discovery is made when one of Goonaese men paddles a canoe over the tepid Gulf of Mexico to warn the Wongoese that the bad Roman ape men without a GPS could not find Sabine, and will now raid Wongo in order to capture mates.

They combine….forces to fend off the even uglier ape men, well, there were two men in ape suits. The combining leads to attentions and tensions between and among the Wongoese and Goonaese. The result is like with like. That is a guess because the action is, ….wait, what action? The movement is, whoa, what movement? What dialogue? What direction? Yes, what direction? The pace is not leaden only because there is no pace at all. It seems to be the only credit of the IMDb for each member of the cast and crew in the Florida production. It seems they learned from this experience.

The 2.1 from 10 is a result of masochists rating it 4.0+ on the it-is-so-bad-it-is-good criterion. Still it a rare film that starts with a voice over from Mother Nature reminiscing about Father Time, and mentioning Aristotle. Florida is nice to look at as long as one does not feel the humidity, the dew-point, and the insects, particularly, the aptly named ‘no-see’ums.’

The ugliness is achieved by paste-on eyebrows, wax in the cheeks, and bad posture. The handsomeness and beauty is achieved by a filtered lens. Once again we have the magic of the silver screen.

The men on Wongo have blue hair, making the fraternity brothers think Superman might have been among them.

Among the things it is not, it is not Sy Fy, but it turned up – and with that title it was irresistible— when researching ‘Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women’ (1968) which led to ‘Women of the Prehistoric Planet’ (1966) which led to this. The previous two titles are Sy Fy, but this is not.

This just in!

There is a musical called, sit down, ‘Wild Women of Planet Wongo.’ ‘Book the tickets now,’ cried the fraternity brothers! It has been reviewed in the ‘New York Times,’ so it must be real.

The fraternity brothers’ favourite a sub-genre of films is ‘Women without Men’ until some come along. The likes of which includes ‘Mesa of the Lost Women’ (1953), ’Prison Women’ (1955), ‘Swamp Women’ (1956), ‘Jungle Women’ (1959), and more.

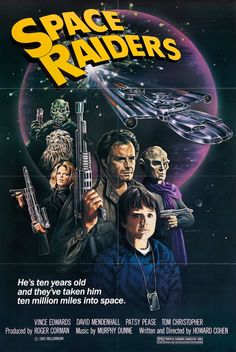

‘Space Raiders’ (1983)

IMDb: 1 hour and 24 minutes, 4.7 from 790 cinemitizens.

Pirates who steal a valuable space ship from a dock find on board a nine year-old boy who hid there when the raid started.

As required by the manual of ‘Star Wars’ knock-offs, the pirates are a mixed lot, one in a rubber mask, one a lady stick figure, one a cowboy without the hat, one New Age sensitive, and blah. Six in all, well, five because one is killed in the raid. One less pay cheque.

His death is one of the better scenes because it shows, unlike so many CGI shoot ‘em-ups the agony and the pain and the loss. However that mood is soon broken by endless games of Tron that follow.

Ben Casey is the leader of the pirates and at fifty-five he moves like he is older, though not wiser, or he would not be here. It is as painful to watch him as an action hero as it was to watch a sixty-five year old Dan Dureya do so in ‘The Bamboo Saucer’ (1968), reviewed elsewhere on this blog. The creaks were nearly audible in both cases.

To pacify the Brat Ben promises to return him home. This promise leads to the death of everyone on his crew, Ben included. That is the spoiler. The corporation from which the pirates stole the ship sends its thugs after the raiders. Because a reward is offered for the boy, entrepreneurial bounty hunters gather. Bigger villains would like the stolen cargo and so on and on.

There is no rapport among the pirates. They act like people waiting on a bus stop. The vacant boy remains vacant. The villains are cardboard, well, rubber masked in most cases while others are CGI robots, and look it. The CGI in space is, well, as boring as CGI always is. The stunts when our heroes roll around to avoid invisible lasers, look like a geriatric exercise class. Yes, that is right, by the way, there are no light beams for the lasers.

The fraternity brothers liked the late scene where Brat dresses Ben’s fatal wound with a glue gun. That is the Ben Casey touch! Let’s see the twelve year old ‘Good Doctor’ do that!

Wikipedia has it that Ben’s celluloid career took a hit because of his addiction to Dame Fortune. He was a gambler, and it consumed him. Didn’t he read the Fyodor Dostoyevsky story ‘The Gambler’ or meet Pete Rose?

The Country Life

Since time began, or so it seems, Country Party, oops National Park politicians have been on high horses about the virtues of country life and country folk. While today they do not readily air those views on national news, they certainly do so when back in their constituencies. Chief among the country virtues touted is always family, family, and family. Cannot have too much family.

The implication is always that city folk are less wholesome, less virtuous, less trustworthy, less family. Ah, for the country life and family!

The reality is that farms are dangerous places for adults and children. All those chemicals that are handled, mixed, stored, and applied, and sometimes (sssh) applied in excess, often by people who disregard and deny unseen threats. Then there are the animals and diseases that attack them and that they carry. Finally, there is all that powerful equipment, occasionally operated by poorly prepared individuals since licensing is not required or enforced.

Some years ago a National Party leader proclaimed the evils of a Labor opponent with explicit reference to country life and family and invoked marital fidelity as an electoral standard. It was only later that all those chemicals got to this proclaimer of the virtues of the country life. As yet no ABC journalist has thought to re-air the archival video of this proclamation in the current context. Wonder why?

Self-appointed representatives of the Fourth Estate in Australia have also declaimed, more to convince themselves than any auditor, that the local media is too mature and elevated to invade the privacy of politicians, in so far as private life does not effect the performance of public duties. Yes, that has been said with a straight face, and I have heard it said by pundits more than once.

The reality behind this forbearance, which no one in the Canberra Press Gallery will admit, is that the many of the extramural activities of members of the political class are with members of the Canberra Press Gallery: member to member. The Gallery has its own version of omertà.

Despite my efforts to ignore reality, occasionally some of it seeps in.

‘Women of the Prehistoric Planet’ (1966)

Run time is 1 hour and 30 minutes of Dali time, rated 2.3 by 850 cinemitizens.

Verdict: guilty of a waste of celluloid.

When this title came up in research on another film, the fraternity brothers demanded it go to the top of the Watch Later List, and so it did. Their anticipation was raised by this tagline on one poster for the film: ‘It’s the battle of the sexes as savage planet women attack female space invaders!’

Slowly the hiss of deflation followed. There are no women to be seen on the pre-historic planet, despite several publicity advertisements featuring women clad in fur bikinis. Yes this was the Year of Raquel in ‘One Million Years BC’ (1966). Despite this let down there are some points of interest in this yarn. The redoubtable Wendell Corey has the lead and the ever present John Agar is the loyal and bored lieutenant.

They are leading a flotilla of three starships heading home after a long mission. The ships travel at ‘near optic speed’ but even so the ‘time dilation’ is considerable. Huh? Check with Einstein. While the explanation, given twice for the dunderheads at the drive-in, is that time is relative between speeding spaceships and rotating planets. While the crew will have aged 18 months on the mission, the folks at home will have aged 18 years. That is keeping it simple for the dunderheads reading this.

That explanation makes little sense but give credit where it is due. It is the only time in the Sy Fy thus far reviewed that time relativity has been mentioned. A C+ for trying.

On the note of trying, there is Comic Relief from which we get no relief. One of the crew makes crass jokes every ten minutes. The fraternity brothers had hoped the boiling mud would get him, but no such luck. Then the giant snake. Nope. Then the leaping spider. Not.

The Red Shirts again get it though; but it is unusual that in this film they have names, Owens and Harris. Another victim is Angel from ‘The Rockford Files.’

No less unusual, there are many women in the crew and none of the men make deprecating remarks about having them on board. ‘Can a woman really be a scientist, explorer, map reader, navigator, switchboard operator, or make tea?’ None of that. However, the women are treated as sex objects, yes, but their abilities are not questioned.

The tension among the crew is race, not gender. Yes, race. Some of the crew are Centaurians, apparently distant offspring of ancient Roman centurions, and they look Asian. Well, the Romans in Syria may have done what we are supposed to do in Rome. Some of the whitebread crew mutter about the barbaric Centaurians. The only specimen of this race we see on the ship freely wanders without about any evident duties overhearing these remarks and biting her knuckle in a barbaric way.

Then the third and last ship in the formation veers off course, and Admiral Corey goes into command mode. By the miracle of cross-cuts we see that some of Centaurians on the third ship have mutinied, though why and to what end it is impossible to judge or to care. Their rebellion caused the driver to blink and the ship hit a magnetic field and down, down, down it went to the planet Solaris. Stanislav Lem’s novel of that name was published in 1961. Did someone sneak a peak at it?

Corey decides to go after it. Note, the admiral slurs his words sometimes and the pea brains who comment on these things suppose he was drunk on set. Well, it would not the first time an admiral was sloshed, but in this case Corey’s biography on Wikipedia indicates his speech was effected by a stroke, and he died a couple of years later. He kept working up to the end because there is no pension plan for supporting actors and he needed the money.

John Agar has no such excuse for mumbling through his lines on the way to the pay cheque and the elixirs it would buy.

The rescuers land and discover many planet years have passed (but only a few spaceship months, see time dilation above). The alienated Centaurian, let’s call her Eve, on the crew takes off on her own to sulk, while a search party looking for the downed ship finds many perils and the Red Shirts pay the price, along with Angel. Regrettably, Comic Relief survived.

The editing is so badly done it is quite impossible to figure out what the search party is doing apart from tripping over props, as its number dwindles. Are they searching for the downed ship? For survivors from the downed ship? For descendants of the survivors? For inhabitants? For a McDonalds? For a better script? No luck.

Eve succeeds where the search party failed. She finds someone, whom we shall call Adam. He looks Asian, too. They get on well together. Ahem. He is a sensitive prehistoric planet guy who has kept his deceased parents from the mutiny ship frozen in clear ice blocks in his cave. Eve does not find this odd.

They continue to get on well together, while the search party number further dwindles. Then Adam and Eve are attacked by the barbarians who live on the planet, and slo-mo replay by the fraternity brothers found that they were all men. Not a bikini in sight. Much confused editing follows. This attack lasts about thirty seconds. No doubt timed for minimum payment to the two attacking extras.

The theme within the adventure thus far was race and racism, Class. Again unusual for the genre at the time, though 1966 was in the midst of the U.S. Civil Rights movement, and the year ‘Star Trek’ appeared with his ecumenical approach to race and nation.

Now pay attention because a spoiler is coming, and it will not be repeated but, yes, St Peter has it on the final examination.

The admiral gives up on finding Eve and the ship takes off leaving her behind with Adam. Got it so far? You got it.

Corey drones in the ship’s log that this blue planet shall be entered into the galactic charts as ‘Earth,’ and the camera pans over a globe with the Florida peninsula dangling. Did Erich like that or what! Adam and Eve were aliens. Why he chose to call it ‘Earth’ and not ‘Blue’ or Yuck’ is not stated.

Which was the worse crime to Alabama audiences, the fraternity brothers wondered? That Adam and Eve were aliens or that they were Asians. That was an entertaining thought.

‘Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women’ (1968)

The IMDb metadata is: 1 hour and 18 minutes of Dali time, rated 2.7 by 1054 who admit knowledge of it.

Verdict: only for the very determined viewer.

Cosmonauts landing on Venus encounter dangerous creatures and almost meet some sexy Venusian women who like to sun-bathe in rocks in 1970s hip-hugging skin-tight pants and seashell brassieres. Sounds better than it is.

How could this be? ‘Why didn’t NASA get there first,’ demanded the fraternity brothers? Good question. The answer is that it is a Roger Corman production. That fact explains the inexplicable.

Corman bought the USA rights to Soviet films because they were cheap and the Sy Fy ones had good space flight effects. He then industriously dubbed them, edited them, cut-and-pasted them, added new sequences, omitted footage and from one Soviet film he got two and sometimes three D-pictures. D is for the Drive-In market. In the course of these exercises he hired impoverished Film School students like Francis Ford Coppola and Peter Bogdanovich to do the work for the experience, not the money.

In this case the original was ‘Planet of Storms’ (1962) or ‘Planeta Bur’ in the original Commie, reviewed elsewhere on this blog. In it a multi-national crew sets down in a forbidding Jurassic Park with a giant robot and stumble around from one perilous situation to another.

Being members of the NRA, they tote six-guns and blast much of the local flora and fauna. They speculate that there may have once been a civilisation on this planet, but now long gone, though the wind, which somehow they hear through their fishbowl helmets and inside their cute little hover craft, sometimes sounds like a woman’s voice. If so, it is no woman the fraternity brothers want to meet.

This was Corman’s cue to add about twenty minutes of footage, interspersed throughout the film, of ‘Bay Watch’ inhabitants who slowly become aware of the invaders and think bad thoughts about them. The leader of this rocky beach party is Mamie van Doren who dons a chef’s hat when she is really mad. There are seven or eight women as described above who stare vacantly at the camera while they communicate via the telepathy of voiceover. There is no sound technician needed, and the women cannot act but they can stare vacantly.

Likewise much of the early going for the cosmonauts is voiced over to set the scene. Dubbing is more expensive than a voiceover.

Among the casualties of the cosmonauts shot-em up is a rubber bird that the women worship.

God is dead.

God is dead.

This causes them to put a hex on the invaders and a big storm blows up as a result. Mamie puts on the hat and the storm gets worse for the Cosmo readers, while for the women it remains California.

The Soviets just barely make their escape, leaving behind the big robot who had forgotten the laws of robotics and tried to save itself at the expense of its human companions. Bad Bot!

The cosmos and the prehistoric women never share a frame together.

The women find the remains of the robot which was disabled by the lava flow of an IOS update gone wrong and gather to worship it. On the Left Coast they will worship anything, Jerry Brown, Zinfandel, alfalfa, and a selfish scrap heap that once was a robot.

This film seems to have been the high point of MvD’s career, topping even ‘The Navy versus the Night Monsters’ (1966).

No doubt it was great fun pulling all this together, but not so to watch it. However, in reading about it, I discovered a whole cache of films about Prehistoric Women! The fraternity brothers have insisted this genre be explored in the coming weeks. At the top of the list is ‘Women of the Prehistoric Planet’ (1966) because it features the man who never said no to a bottle or a part, John Agar. aka Mr Shirley Temple.

‘District VIII’ (2018) by Adam Lebor

Our hero is a homicide detective in Budapest, being of Romani extraction makes him both a curiosity and an asset. He is an asset because some major criminals are likewise Romani. Adolf Eichmann did not get them all.

Budapest is awash with Middle East refugees making their way west to Utopia. Reluctantly, the Hungarian government slows the migration to retain good relations with Western nations, while most people in the government try to profit from human trafficking. There are many wheels within wheels. So many I lost count and interest. Focus is not a word that applies in this book. Suffice it to say that everyone but our hero is corrupt to the core.

There is precious little detecting, and no police procedure to be found. Instead there is a thinly disguised critique of the corruption of Hungarian society and politics. It is laid on with a sledgehammer. The fittings and furnishings of every room are detailed. The attire of each actor spelled out. In this combination of Vogue and IKEA, motivation, character, and plot dissolve. Then their situation is traced back to the dire situation of Hungary trapped between Communism and Capitalism. The level of analysis is that of the ‘National Inquirer.’

There is some Gypsy lore and that was interesting to this reader, but it was not integrated into the plot for the simple reason that there was no plot. Just a pastiche of attacks on Hungarian society and politics. Everyone is either corrupt or incompetent. Fortunately some are both and that leads to their downfall.

In its eagerness to peach the book reminded me of the latter volumes of the Martin Beck series from Sweden. This series started out as low key police procedurals through which a reader learned much of Sweden but the books slowly became sermons on the evils of Swedish capitalism, as if the genocide of the 1930s Socialist eugenics program was somehow the good old days.

‘The Last Days on Mars’ (2013)

IMDB data: 1 hour and 38 minutes, rated 5.5 by 31,661 pre-pubescent boys,

After many months on Mars, the crew of the Irish Space Commission are packing up for a rendezvous in nineteen hours to return to Earth. The digits on the clock flip. (Clocks don’t tick anymore.)

Wait! Irish in space? Well the production was partly funded by the Irish National Lottery and directed by an expatriate Irishman who will never return to Eire. Plus the logo on the gear is ISC. Nothing gets past the fraternity brothers.

The set-up in Act I is good. There is a large and mixed team that represented the variety of Ireland, though no one mentioned James Joyce. Having been on Mars for six months, they are tired, care-worn, testy, and eager for the return flight. The gear and procedures have verisimilitude. Jordan once again doubles for Mars as it did in ‘The Martian (2015) and ‘Mission to Mars’ (2000), both reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

But…., yes, there is a big ‘But’ coming. The production team evidently thought getting to Mars, landing on Mars, surviving on Mars, doing science on Mars, leaving Mars, making it back to Earth, that all of this is boring. So instead of teasing out the drama implicit in the list above the film swerves to a creature feature. Oh hum. This is Act II.

Turns out in the last hours, one of the crew out spelunking, finds life, a microbe, which infects him and goes on to infect others, turning them into Zombies! Sometimes they remain in their space suits and sometimes not as they wander the Jordanian desert. These Zombies want company, and get it by infecting others. Is this a case of the selfish gene?

Becoming aware of the microbe, the leader the mission gives all kinds of orders that no one obeys. It reminded this writer of trying to get the fraternity brothers ready for Monday. Pointless.

Needless to say this ineffectual leader is one of the first to turn, first dead, then animate again! That is the nature of the zombie, despite the liberties taken by many scriptwriters.

With all the yawning, I lost count of the crew, but say Ten Little Indians. They all succumb but one who makes the rendezvous in Act III. Is he a carrier? That would surely explain the Living Dead Trumpettes.

Did the Irish Film Board recover any money on the Irish Lottery investment? The money was spent in England, in Jordan and in the USA. The fraternity brothers did not hear any Irish accents in the crew above chewing popcorn and slurping sodas.

‘Atomic War Bride’ (1960), aka ‘Rat.’

IMDb 1 hour and 35 minutes, rated 6.1 by a paltry 179 ra(n)ters.

Jack and Jill are about to get married on a fine spring day somewhere in Europe. Jack buys flowers for Jill as he hurries to the get himself to the church on time. In the street a one-note newsboy shouts, repeatedly, ‘War declared!’ Jack only has ears for church bells and ignores this declaration, while others in the street react in alarm, amusement, and denial.

The release title was ‘Rat’ which is ‘War’ is Serbo-Croatian, the language in which the film was made in Zagreb of the Tito’s Legoland Yugoslavia.

Mistaking him for Kevin, everyone asks Jack what will happen. His parents must have been Pollyanna and Dr Pangloss because he is exhaustingly optimistic about everything. For him an empty coffee cup is an opportunity to do without coffee, and not a life threatening disaster. Figure that out! Everything is fine. Everything will work out for the best. All is good. All is ad nauseam. He is the kind who would grin through a 360 degree review, because he enjoyed it!

While Jack and Jill are at the altar the bombs start falling. He keeps smiling. As they leave the church with you-know-what-in-mind he is press-ganged into the army. Next thing you know he has changed costume and is parading around in a uniform with a firearm. More bombing occurs, but Jack is sure wiser heads will prevail. As if.

While in a bomb shelter he suggests people proclaim their desire for peace. They do. He is then a traitorous ringleader in a rebellion, apprehended, and sentenced to be shot. He keeps smiling, while inviting the firing squad and the sentencing officer around for dinner when all this is straightened out. Which it will be very soon!

But then it gets brighter than a thousand suns. Afterwards while crawling around in the rubble, Jack meets the Prime Minister who assures him that war was the will of the people per the ‘White Book,’ on which more later. The shock wave blew off most of Jill’s clothes and that briefly piqued the interest of the fraternity brothers. As the radiation washes around them, Jack and Jill retire to their new apartment – a ruin – and he sets about making coffee. She does a swan die. Will Jack wake up to reality now? Fade to black.

The end.

Well, it is an anti-war film of sorts, with special reference to atom bombs, coming out of the precariously non-aligned patchwork that was the workers paradise of Yugoslavia. Given the post-Tito blood bath of that part of the world, I wondered if a contemporary audience in Belgrade would have perceived the origins and ethnicity of each of the players. Is that why Jill is played by a Pole? To confound that ethnic typing and residual animosity there in paradise? Or to gain it box office in Warsaw?

There is a cast of thousands, and it looks like the army cooperated, given all the marching men, weapons on parade, and fly overs. In the time and the place that cooperation would make it an official government film in all but name. It was bought, edited, and dubbed for the US drive-in market as background to anatomy lessons.

The cast and crew were among the best in Belgrade but this is not their best work. Most of the failure goes to Cesare Zavattini, the script writer who settles for simple-minded nostrums and witless Chaplineque situations, though that may have been what the producers wanted. Hard to believe the same typewriter produced ‘Shoeshine’ (1946) and ‘The Bicycle Thief’ (1948).

The ‘White Book’ the grovelling prime minister carried, seemed to be a report on public opinion regularly prepared for him. Gallup was not involved. A short search on Dr Google produced no enlightenment on the subject. But the combination of ‘White Book’ and Yugoslavia produces many hits, false positives.

The comparison has got to be ‘La Jetėe’ (1962), reviewed elsewhere on this blog, which is far more imaginative, creative, enticing, and enigmatic. It gets across more in its running time of twenty minutes than this feature length film does in ninety minutes.

‘Escape from Mars’ (1999)

IMDb 1 hour and 40 minutes, rated by 527 cinemitizens at 4.8/10.

In the year 2015 the first mission to Mars consists of Canadians! Well, they know cold weather and there is plenty of it on Mars, despite the sunbathing of ‘Robinson Crusoe on Mars’ (1964), reviewed elsewhere on this blog. The Canucks are employees of a corporation. Shades of the Alien franchise.

With neither a creature, sex, nor a Hollywood name, its 4.8 is the result. It moves slowly and there is good deal of the science and engineering of spaceflight. The Laws of Physics are so hard and implacable that no creature is needed to complicate things. These Laws kill without hesitation or mercy. They are like a McKinsey manager managing.

We have five crew, two women and three men, one a Russian. We are guided along the way by a television news announcer. Everything is played up to satisfy the corporate sponsor who has invested frequently told billions of loonies in the enterprise.

They make it to Mars and land. Together the co-commanders (one for flight and the other for ground). a man and woman, take the first steps on to Mars. This was a nice touch. The exaggerated television account was a gentle satire that escaped the reviewers consulted.

Then the Band of Five are struck by a pile of clichés, namely meteors, which do not burn away in the thin Martian atmosphere, and pelt the landing craft – a shuttle mock up. Oh oh, even as all the onboard systems fail one by one, the crew gamely sends back to Earth upbeat video messages to satisfy the KPIs in their contracts which require them to remain plucky unto death.

Yes, it is starting to sound like ‘The Martian’ (2015) but there is much less scientific detail here and much more about the tensions among the crew in this dire situation. Ergo it is a character study of this crowd on the planet Otranto, and how they — individually and collectively — react to the dread they face.

It is all very Canadian. Low key does not quite describe it. Catatonic is closer. No one goes all Hollywood ballistic. Nor, thank the stars, is there any comic relief. A comparison might be ‘Operation Ganymed’ (1977), reviewed elsewhere on this blog, but this latter film has more mystery and drama. It, too, is about science, not CGIs. But the fraternity brothers liked the name of the mission, Sagan, and that it was not explained. Either one gets it, or one doesn’t. It is not often they respond to such subtlety but they did this time.

There is spelunking and in a cave is to be found a biochemical reaction that bespeaks water. Sure enough there is a drip. No! Wait, that is the director. ‘The Europa Report’ (2013) compares on this point. It is reviewed elsewhere on this blog.

All problems are solved when one of them dies. Without him, they have food and fuel to ascend and return which they do. It seemed all too easy after the built-up of the hopeless situation. Likewise, there was talk earlier of contamination which disappears in Act III.

It was filmed in Winnipeg, of all places, but they know cold there, too.