IMDB 1 Hour and 22 minutes @ 6.8/10 from 4295

On a mild autumn evening a young couple doing anatomical research in the long grass are disturbed by a rocket screaming overhead. It rattles the crockery and sets off the dog at a nearby farm. The eternal British Army Scotsman Gordon Jackson takes up arms to deal with the disturbance, but well none of his previous cinematic experiences has prepared him for rockets and it is his last scene above stairs. No, he doesn’t get zapped but calls in Professor Quatermass. Gordon went on to his next gig.

The QX was to send a three-man rocket into orbit and return it to Earth. While his rocket kit was home made, he has Lionel Jeffries from the Ministry ineffectually dogging his steps as he orders about everyone around with contradictory demands. Prof Q certainly likes being the boss!

After much dallying they pop the door and find one spaceman much the worse for wear. Where are the other two? Mysterious, indeed. Speculations follow.

Meanwhile, the Survivor, who gives a devastating performance, is rushed to a hospital for returned spacemen and guarded by a dolt. The spaceman’s wife decides a private hospital would be better but Prof Q wants to study the Survivor by bellowing at the nurses. Wife decides to spirit him away. This does not go well.

Now he is on the loose, wandering and wondering around. Some very nice scenes of his encounters. There is an inner struggle and the man is losing to the protoplasm. Oops, that is a spoiler!

As his humanity recedes, the protoplasm’s appetite increases. There goes the zoo. Gulp. At this point my imagination turned D.C. How long are zoo animals there safe from the GOP protoplasm?

The rest is a police procedural to track him, which has become an it, down. They do so in Westminster Cathdral. Well a mock up of it since they film company was denied access to the real thing. There they turn to the mad scientist’s old friend, electricity, to fry it. Success! Fried protoplasm is on the menu.

The intrusion into Westminister is cleverly done to juxtapose a bland high arts program on the building with this thriller. The former represents most BBC television at the time, fussy, erudite, recondite, arcane, dusty, in contrast to the whiz bang of Quatermass and his happy band of alien hunters.

Everyone is exhausted! Aghast! Relieved! Many sighs are heard. Wife is not consulted about any of this. Meanwhile, Professor Quatermass has learned his lesson and strides off to build a new protoplasm-proof rocket.

It seems this first rocket while in space passed through matter that entered the ship by magic and absorbed the crew. That is where the missing two went. Since this was a new cuisine, Proto proceeded slowly,and was only starting on the third when the ship under remote control from the ground crashed interrupting the anatomy lesson.

This story had aired in the BBC in 1953 in six parts to a great reception. That emboldened the entrepreneurs who would become Hammer Films to hire the author, Nigel Kneale, to re-write the story into a continuous film script, Kneale went on to write more Quatermass, so much it is hard to keep it straight. He also wrote one of the best things I have sever seen on the box, namely ‘The Stone Tapes’ (1972).

This film has the look of a quota quickie because the Yankee action man Brian Donleavy plays Prof Q, and does so with evident relish. Quota quickies are explained elsewhere on this blog. The essence is that they were cranked out to meet local content requirements but often had an American actor for marketing there. Most were as quickly forgotten, but not this one. It triggered more Quatermass films and encouraged Hammer Films down the genre path of Horror.

In 1955 an X-rating meant adults only, and Hammer accepted that readily by incorporating it in the title as was the case with some other films like ‘The Man from Planet X’ reviewed elsewhere on this blog. What children were then denied they can get today on video games.

‘Solaris’ (1961) by Stanislaw Lem

Deep space travel is routine and many planets have been surveyed. There was nothing of interest about the planet Solaris and so it was ignored for years. An astronomer then noted that its orbit was odd. Because it circles a double star, one red and the other blue, its orbit should be erratic but it does not confirm to the laws of physics. (The same is often said of the fraternity brothers.)

Solaris receives closer inspection. It is nearly completely covered by an ocean with only a few rocky outcrops like a few tufts of hair on a bald man’s head. Landing parties use those but cannot find anything relevant, but they do see that the ocean’s motion is varied and unexpected. Again they wonder about the laws of physics. After years of study, the field of Solaristics concludes there is an intelligence in the ocean regulating the orbit by some means. The book is replete with a gentle satire about academic specialisation as an end-in-itself.

More studies fatten cvs and efforts to stimulate communication are made using radio waves, ion streams, pictures of Mother Teresa, neutrino bombardments, pamphlets, and an unauthorised use of intense x-rays and other more destructive means to no avail. Solaris seems immutable like reasoning with a Republican.

A research station is placed in orbit to observe with a crew of three on a three-year stint and has been there for years. Then the one day commander of this station a the time requests base to send a psychologist. Isolation in space does lead to mental problems so shrink Kris Kelvin is dispatched. The novel opens with his arrival and the preceding information emerges piecemeal.

No one greets him. Odd. No one seems to be about. Odd. Moreover, there is disorder everywhere. This is no way to run a space station! He finally finds one of the scientists cowering behind a barricaded door. The other scientist will not leave his lab and speak to Kris. The plot thickens.

The commander who asked for the visit committed suicide that very morning. Odd! What to do? Kelvin decides to examine the corpse in the best tradition of the police procedural. En route he hears barefoot steps and passes a large black woman in tribal dress. She blankly ignores him. He is astounded. That is only the beginning.

Cutting to the case, each member of the crew has a spectral guest. It is someone a memory of whom is found deeply etched in his psyche. This is not necessary someone he wants, but it is the deepest, most ingrained memory. In Kelvin’s case his guest is Harey, a girlfriend who also committed suicide, so that he feels guilt, regret, and remorse.

These guests, the crew concludes, are from the Solaris ocean which is engaged in a Communicate with the Humans Project of its own. The Solaris guests have assumed the identities they have because of the importance of the memories to each scientist. Once embodied the guest seems to know a lot but have no memories of specifics. Harey is sweet and clingy but has no idea how she came to be there, but strangely she knows things about Kelvin that occurred after her own death. Evidently to some extent the guest can tap the host’s mind. But the commander’s guest has remained after his death! Talk about overstaying a welcome!

Various methods are tried to analyse the guests and to eject them from the station but they keep coming back. Meanwhile, Kelvin finds it easy to have Harey around. They engage in many conversations as she becomes aware that she is some kind of aberration, clone, replicant, or dream.

She is a virtual reality girlfriend. She is self-conscious, intelligent, capable of learning but she can never be more than Kelvin’s memories of her. In that way she is limited, and realising all of this she grows despondent. Of course the fraternity brothers wanted to know whether she is full functional but that is not made explicit.

There are many conversations with one of the scientists about the ocean, god, creation, Amex bills, morality, metaphysics, ontology, bratwurst, on and on. It is talky. We never find out about the other guests, nor is there any contact with the ocean. It is all trip and no arrival.

Is the omnipresent but uncommunicative behemoth of the ocean of Solars a metaphor for…. Soviet Communism viewed from the observation platform of Poland? Or just a yarn?

It is a meticulously written and original work to read it today, let alone more than fifty years ago. I sat through the Soviet 1972 film version years ago without it making any impression on me apart from the cruel and unusual length of three turgid hours.

The Grand Jury at Cannes is made of stronger stuff than am I.

The Grand Jury at Cannes is made of stronger stuff than am I.

But in the age CGI Über Alles I expect it will have to be done again one day. No, I have not seen the Yankee 2002 version either, well, except for some scenes that I came across somewhere.

Channel flipping, no doubt.

The context of Dunkirk.

Before I review the recent film, what follows sets the scene for the historical event, details largely absent from the film.

Staff work is never celebrated and when it works, it passes unnoticed. The Royal Navy began planning for a mass withdrawal of the British Expeditionary Force, including directly from beaches, six days before the first lift occurred. Procedures were elaborated, the wording of simple and clear orders hammered out and communicated, beach wardens designated and briefings written for them, auditing began of flat-bottomed small craft on RN vessels, estimates made of rates of embarkation per hour under fire, distribution of medicine and field dressings to RN ships begun, drafting medical personnel and assigning them to ships started, listing civilian craft in southern ports was started, decks were cleared on RN transports, and so and on. Operation Dynamo started long before the first Tommie got wet.

Operating at the limit of the range of fighter aircraft from England, the Royal Air Force flew more than a hundred missions over Dunkirk during the evacuation. However, no one could guess at the timing of German attacks and so The RAF was often absent when the Luftwaffe was present and vice versa.

Nearly all of those evacuated were taken off piers and moles on RN boats and transferred to warships. The sea around Dunkirk beaches, by the way, is shallow, meaning the larger ships had to stand well out, and it was a long transfer from shore to ship. Six or more RN ships were sunk by German air attacks with much loss of life. At the initiative of their captains, some French ships also loaded troops, and likewise some French ships were sunk.

The French defence of a line around Lille resisted for four days against a superior force holding ten German divisions off Dunkirk, and that reduced the pressure on the perimeter. In the end much of Lille was levelled by house-to-house fighting. The town of Dunkirk itself was obliterated by artillery fire. By the way. These battles are seldom mentioned in the British accounts of Dunkirk. By the way, Lille was the hometown of Charles de Gaulle and members of his family died in this struggle.

Nearly all of the little ships that participated in the exercise had Royal Navy personnel on board, though often a very junior cadet, partly this was to honour the legality of impressing the boats into service and indemnifying the owners and civilian crew. The little ships ferried men from the beaches to the ships, and some sailed directly back to England, like that of Mr Miniver. One estimate suggests six thousand men were evacuated directly to England by little, civilian water craft. I have seen that said as ‘only six thousand’ out of the more than 330,000. True that is less than .02 percent. But it is 6,000 individuals welcomed home from the cauldron and as a whole they amount to a light division which later any general later would be glad to have.

While there was planning and preparation, there was also disruption and confusion. Much fell to the initiative to those on the spot. That initiative worked as well as it did in large part because of the planning that set the scene.

French troops had fallen back onto the line Dunkirk – Ostend which was slowly collapsing. There was no plan for them to do anything but fight. Communication between French field commands and headquarters were cut, and communication among the field commands was likewise nearly zero. (Much of the responsibility for the loss of communication must go to French High Command which refused the use of field radios.) Without communication, without orders, responsibility fell down the chain of command ever lower in an army that did not prize initiative.

When the British evacuations began, the French troops in the area had no orders. Some individuals made up their own minds and tried to join in. The best way was to change coats by peeling one off a deadman and trying to look English.

At times French officers on their own initiative tried to board their men in units, and some were successful and others were turned aside. This refusal to board some of the French was reported to Prime Minister Winston Churchill by British army officers, and Churchill immediately ordered that there be no discrimination but rather first come, first boarded. This applied to the French, the Belgians, the Dutch, and even some Poles and Czechs who were there.

There was the germ of a plan, hatched by the French Under-Secretary of State for War in the Reynaud Government to withdraw to the Cotentin peninsula in Western Normandy. Troops evacuated from Dunkirk could be fed into that plan. That Secretary of State was General Charles de Gaulle.

The 100,000 French troops disembarked in England from Dunkirk spent only two or three days there. They were entrained to Bristol, Swansea, and other western ports and shipped to Bordeaux while the war continued.

While French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud wanted to fight on, the generals at the French meeting table were defeated. They convinced the majority of cabinet that further resistance was futile. The cabinet asked the President, a figurehead, to empower Phillipe Pétain to ask what terms the Germans would offer. That was his mandate when named prime minister of a one-man government. Instead he surrendered without any effort at negotiation. Doubtless negotiation would have failed but the effort might have bought a little more time and much more dignity. But that surrender without the effort rendered the legitimacy of his claim to government suspect to many.

While 200,000+ men of the British Expeditionary Force were evacuated at Dunkirk, thousands of others were evacuated about the same time along the north coast, and later more than 100,000 others from the west coast of France. These other evacuations were less heroic and are not well known as a result but each was done in difficult circumstances. The shallow waters off Dunkirk kept the U-Boats away but not so off Bordeaux.

That Dunkirk became a moral victory has a simple but overlooked explanation. With the impulses of a democratic politician, Churchill who had become prime minister on the day Dynamo started, went to Waterloo Station in London to see for himself the battered and wounded troops returning from the south coast. As he walked among them, they cheered him and he they; he put his hat on his walking stick, and his resolve to fight on multiplied. Democracy at work. They were beaten but not defeated and he got the message.

At Dunkirk the decisions were many. When the Germans broke through at Sedan, one prong drove to the sea to cut off the British Expeditionary Force there and the two French armies in Belgium, while another drove at Paris to decapitate the French government. The French resistance was stiff in some places, like Lille, yet in other places it dissolved. The RAF decided to withdraw its aircraft from Frenchg airfields to England, lest their airplanes, fall into the hands of the advancing Germans, to save its assets to fight another day. This RAF withdrawal outraged many Frenchmen who hoped they would fight on, come what may. Here national interests diverged among the Allies. It seemed all or nothing right now for the French, but the English could wait to fight again another day.

Hmm, but the French did have an alternative, one that Reynauld proffered without success. To take the government into exile to Algiers and continue the war from the vast French Empire with the imperial army. There might have been another day for them, too. One of his generals had an airplane fuelled and ready to do just that.

While some French officers thought the British evacuation was a betrayal, that sentiment is largely hindsight. At the time, a withdrawal kept those troops, a third of them French, in the war and not in prison camps which was the fate of those who remained. Most of the defence of the Dunkirk perimeter fell to the French who held longer than the Germans had estimated they could.

That the Germans did not go all out against Dunkirk seems to be the conclusion. Why not? Partly because the strategic goal was Paris, and not Dunkirk. Most of the Luftwaffe efforts were directed to that end. As terrible as the Luftwaffe attacks on Dunkirk beaches and shipping were, most of its efforts went to paving the way for the advance on Paris.

It is also true that the German forces attacking Dunkirk were at the end of an attenuated and nearly exhausted supply line. Petrol, ammunition, medical care, medicines, fresh water, tires and treads, field dressings, food, oil, replacement parts, boot laces, all of these were depleted, as were the men. Machines were breaking down from two weeks of continuous use. The Germans had to slow down to recuperate and re-new energies. The horses that carried the vast bulk of the supplies were knackered.

There are other explanations that seem less credible. One is that Hitler gave the stop order, rather than just agreed to it, to open negotiations with England. Some connect this speculation to Rudolph Hess’s earlier flight. It seems a long bow. The best way to negotiate with England would be from strength by capturing the British Expeditionary Force which had in its ranks the vast bulk of England’s professional army at the time, that part which was not in the impregnable fortress of Singapore.

Another explanation is that Hitler wanted his genius recognised and gave the stop order to show the generals who was in charge. It fits the man, but it does not explain why the stop continued as long as it did. What explains the duration is the re-supply of the Wehrmacht and also that the forces in the north had a second-order priority compared to the forces driving onto Paris. This latter offensive is neglected by British accounts because their were no British troops involved, only French, of whom thousands died.

There was no hurry because the German supposition, based on its own staff work, was that most of the men trapped in and around Dunkirk had no where to go. What surprised the Germans was that the evacuation worked. Their staff work concluded that an evacuation would lift about 40,000 men plus of minus ten percent, and leave the rest. Ergo, the German General Staff did not see any reason to spend its assets at Dunkirk.

While the Luftwaffe attacked the evacuating ships at piers there were few U-Boat in those waters. Most were patrolling in the North Atlantic. German planning did not anticipate the concentration of Royal Navy shipping in the channel and so the Kreigsmarine added little to the effort. Moreover, the shallow waters of the English Channel are not U-boat friendly. But the British staff work had created the naval concentration in advance, including pulling ships back from the Norway campaign and stopping others from sailing to the Mediterranean.

Among the heroes of the Miracle at Dunkirk are scores of RN staff officers who worked around the clock for a week of more to set it up.

These ruminations were stimulated by the release of the recent movie but I did not bother to see it on the assumption I would find its inaccuracy annoying, curmudgeon that I am. No doubt others who saw it will now feel they know the history, having ‘seen the movie.’

No doubt the account above is incomplete and perhaps inaccurate in part, and corrections are welcome.

‘Black Out’ (1996) by John Lawton

A police procedural set in London during the Little Blitz of early 1944 when V rockets rained down.

The murder of one and then two resident aliens, with a third suspected, is well out of the ordinary. Our hero becomes obsessed by it to the neglect of other duties but his superior, though vexed, is indulgent, and even supportive.

There is a large and intrusive US military establishment in London and it somehow seems involved In the mysterious deaths, so Plod noses around there, too.

There is much to’ing and fro’ing down mean nocturnal blacked out streets, many low lifes taking advantages of the circumstances, some patriots, and a lot of stoics hanging on.

I never did understand what the villain was doing and there is no wrap up at the end. What motivated him in targeting those three men remains unknown to this reader. Still less could I tell if his motivation was offical business, entrepreneurship, or just sadism.

Likewise I could not fathom his living doll who dutifully seduces Plod and then tries to kill him.

The author has more success with some of the supporting players like the wooden top who deals with the first murder, and the US army sergeant, though she is shallow, at least she has some vitality but her backstory was superfluous and she would not have worn battle dress in an office. I also like the brief role of an army guard who holds up Plod while Ike gets into a car.

That Plod is too dumb to realise the two women he has his way with are using him, is nicely done but in the end I am not sure that was intentional on the part of the author.

Plod’s own backstory which is parcelled out throughout the story is tedious and irrelevant, though it could have connected to that of the sergeant with some thought. Missed opportunity there.

The coda in Berlin was just too long a stretch. This reader was through long before that but kept reading hoping for enlightenment about the plot but none came.

John Lawton

John Lawton

I liked the setting and set up enough to read another.

‘Unearthly Stranger’ (1963)

IMDb metadata: 1 hour and 18 minutes, 6.6/10 @ 320 opinions

Funded from the tip jar at the tea room, the sets are bare, the effects ordinary, but the scene is well set and there is enough mystery to hold interest. Strangely, John Carradine is not in it.

It opens with a wide- and wild-eyed man in fear running down a dark and empty street. He looks back as if he is pursued. In a close up, John Neville is bathed in sweat. A paranoid atmosphere is established with a minimum of fuss. Neville ascends a circular staircase, working up more sweat, bursts into an office and starts a reel-to-reel tape recorder to tell the story in flashback.

Neville is a scientist in the Space Research Centre somewhere in Britain (where the streets are devoid of cars).

We learn in the flashback that he has just been promoted to the top job and that he has also just got married after a whirlwind romance in Switzerland. Is the conjunction of these two events a happy coincidence? Or has the script writer set it up? Guess!

The Space Research Centre consists of a receptionist, a large map of the moon on the wall, two offices, a chrome dome Philip Stone (who has been in everything), and Neville. His predecessor, whom we see ever so briefly, blew a brain gasket and died. Young, vigorous, and cheerful, yet he keeled over and the autopsy showed blood vessels shredded in his grey matter. Ouch.

Enter the rotund security officer,

Mother (as he was later to be in ‘The Avengers’), who tells Chrome Dome that a number of astro-scientists have blown brain gaskets in England, USA, and the USSR, though this latter report is suspect. Is looking at a large map of the moon the cause? What other explanation could there be, Erich?

Well, the fraternity brothers took a look at the wife. Ah ha! Turns out other brain-blown scientists also had new wives. Oh, ‘nocturnal over exertions may be the cause,’ they cried. Rotund does not even consider this obvious line of peeping.

Neville, eyes turned to the heavens, speculates that ‘they’ (hint) up there may not want us to get there.

However, attention now swings to Wife. It seems Neville knows nothing about her, ahem, apart from that, and it also seems, as he gradually realises, she took all the initiatives that led to the marriage. What he just assumed was his magnetism can be interpreted otherwise.

At times he seems to have suspicions of her, and at other times he is quick to defend her from Rotund’s insinuations. Neville is clearly in thrall to her. The fraternity brothers terminology is not suitable for a family blog like this.

But even the smitten Neville admits she has quirks. She sleeps with her eyes wide open all night. (Androids do this in other films.)

Okay. She has no pulse. Okay. (The fraternity brothers immediately spotted that as a trait of Venusians, per ‘Stranger from Venus’ [1954], reviewed elsewhere on this blog.) Moreover, she grabs a red hot casserole from the oven bare-handed with no ill effects. Later, the tears she cries burn her skin. What does all this add up to? See title above.

Aware of these oddities, Neville manages not to add them up. Nor does he connect the dots to his earlier speculations about what ‘they’ up there might not want. Thrall, indeed.

Wife gets misty at the sight of children. Hence the tears. Then when Neville cracks the formula for something crucial, who knows what, more tears come, because…. It is time to blow another brain gasket.

Spoiler.

She is indeed one of ‘they’ on a mission to stop the Space Research Centre from meeting its KPIs. In cinema-land few, if any other, aliens are women. What we get here is an alien who is conflicted, who has compassion, who has maternal instincts, as well as asbestos hands. This is a rarity in the Sy Fy genre. While some come in peace and do good works, no other alien to date falls in love and finds life on Earth good enough to stay. Wife does not want to hurt Neville, and she would like to have children.

Okay, okay. This is a pre-Liberated Woman who just wants to be a wife, homemaker, and mother, but in the context it is a volte-face. Of course, the fraternity brothers had a lot of questions, which are best omitted, about alien women.

When she wimps out of blowing up Neville’s brains, the receptionist steps in. Turns out for the last twelve years she has been erasing the blackboard every night, so that the scientists have had to start the formula over each day. This trick is called a Penelope among the Sisterhood. None of the big brain scientists have noticed this, not even the chrome dome boss.

However Chrome has figured how to overcome an alien. He grabs a sock from the laundry basket and the odour drives her to jump out of the window. Phew! Whew! Like Wife, she just vanishes. There today, gone today.

But there are plenty more aliens in the sea, since the last shot is of a group of women having a look. Gulp! Are they more of the Lunar Sisterhood? We’ll never know until the sequel.

No one smokes. Now that is odd in a piece from this period. No pipe fiddling. No cigars, No cigarettes.

Some reviewers call this an alien invasion film, but not so. there are aliens on Earth as agents of influence, but there is no invasion, nor a threat of one as long as the blackboard is kept clean over night. Brains are then safe.

The Cold War is there in the distrust of the Russkies, but the aliens are not a metaphor for them, or are they?

‘The Year of the Sex Olympics’ (1968)

IMDB meta data: run time 1 and 45 minutes; scored at 7.3/10 by a paltry 124 voters.

‘Coming sooner than you think,’ is the opening title card. About time, cried the fraternity brothers!

Made fifty years ago, this film is an anticipation of reality television, even before ‘Death Watch’ (1980).

The set up? The televised trials for a place at the next world Sex Olympiad are underway in a television studio. Watched from a control room by the bored producers, clad in paisley pajamas, who are dedicated to keeping the viewers apathetic in a society where

‘it is better to watch than to do.’

They watch and so do we. The vicarious sex on the telly is to sate the libidos of the audience so that there is less reproduction. (Pornography has never done that for the fraternity brothers.) There are other sex program catering to the artistic. Another program is aimed at reducing the appetite for food through custard pie throwing. Very Three Stooges. There is a joke about this in the credits with a long list of consultants on pie throwing, including Bernard from ‘Yes, Minister.’

Those jammies.

Those jammies.

In general the purpose of television is to quell the emotions, drives, and impulses of people because they cause conflict. The goal is a quiescent society. like Canberra on Saturday night.

This situation has gone on so long that the current generation we see no longer seems to know the larger context or purpose or the historical evolution of the industry and the society it serves. It just is this way.

Everyone speaks a clipped functional language. The television producers are High-Drive people. The audience they cater to consists of Low-Drive people, the vast majority. That translates readily to the world of Channel 7Mate where the producers cater to an audience they despise and make millions doing it. No one goes broke underestimating the tastes of that demographic where urine drinking is a competitive sport.

Finding the balance in this television game is tricky. Nat with eyebrows that often speak for themselves is pressured from above by the Controller, a standard BBC term, to improve his programs and threatened from below by a underling who wants his job. Situation normal in an organisation but mercifully this depiction is pre-KPI so there is no cloudy and vague McKinsey-speak further to confuse matters in the name of clarity.

Two disruptions occur. First an artist arrives in the studio and he wants to upset people with horrifying pictures. Think of Evard Munck’s ‘The Scream’ or the Twit in Chief smiling. Ugh! These people are indeed horrified by the art. The studio High-Drives are so cocooned they have never seen an unpleasant sight. The artist tries to disrupt a broadcast to show one of his pictures and becomes one himself when he falls to his death!

Eyebrows, however, finds the pictures fascinating, albeit unsuitable for broadcast. He is, perhaps, not quite as superficial as he seems, then into his life comes a personal crisis when a child by his first wife is tested as Low-Drive, which will reflect badly on him. He has no interest in Ex or Child except as they show in his file. He is a very model of a modern McKinsey manager avant le mot and only thinks of his KPIs.

The idea emerges of isolating a couple on a deserted island amid cameras so that viewers can watch them cope. Eyebrows and Ex volunteer with Child. These three missed Scouting and know nothing. They do not know what fire is let alone how to start and maintain one or to pull a vegetable out of the ground on the windswept rain-soaked island in Holland Park to which they are consigned.

They have copious instructions from Wikipedia on an iPhone which are frequently consulted. Eyebrows had an iWatch in the studio bit he did not take it to The Island where he went low tech.

The program is called ‘Living Life.’ The audience finds it amusing and it is a hit. The audience by the way is represented by a focus group of twelve garbed in pink sweatshirts and pants. These are the Low-Drives of Channel 7Mate.

Without the professor from Gilligan’s Island, Eyebrows and Ex are hopeless. They have been spoon fed so long that they only know the shape of the spoon. Child falls, breaks an arm, and slowly dies of an untreated infection.

The sweatpantsers find that hilarious. Ratings soar. (See, like ‘Death Watch.’)

The inevitable comparisons are the E.M. Forester story ‘When the Machine Stops’ and George Orwell’s ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four.’ Though as to the latter, there is no hint here that there is a regime oppressing people per Orwell but rather a commercial enterprise giving the Pink Sweatpants Nation what it wants, when it wants it, and how it wants it. Is not that broadcast populism, or democracy? Responding to what the people want is one definition of democracy.

This is another gem from the fecund typewriter of Nigel Kneale. The players include Reginald Perrin and the estimable, but here very young, Brian Cox. I found it on the Internet Archive.

It was filmed in colour but only a black and white archival print remains. The expensive colour film was reused though why the BBC did it in costly colour at a time when there very few colour televisions to see it on is anyone’s guess.

Inspired by this viewing, I will look for ‘Death Watch.’

‘Space Trucker Bruce’ (2014)

IMDb meta-data, 1 hour and 27 minutes, rated 5.1/10 from 60 voters.

A road movie in space as the lonely space trucker Bruce with 20,000 tons of Iowa hog fat picks up an escape pod passenger. Not quite a hitchhiker but close to it.

They get to know each other and then they encounter The Dark Object and they struggle to survive. They bond. Bruce is in the Channel 7Mate demographic.

Moral, space travel is boring. Subtext, watching boring space travel is boring.

Very.

This is a no budget exercise written, produced, directed by one of the actors. See. It was posted to You Tube by the maker by way of a release.

I managed to watch it to the end but then, strangely, forgot about it until now quite a time later.

Not to be confused with ‘Space Truckers’ (1996), which on the IMDb ranks at 5.2 or a mere 0.1 higher despite its much bigger budget and some fine actors, e.g., Dennis Hopper, Charles Dance, and more.

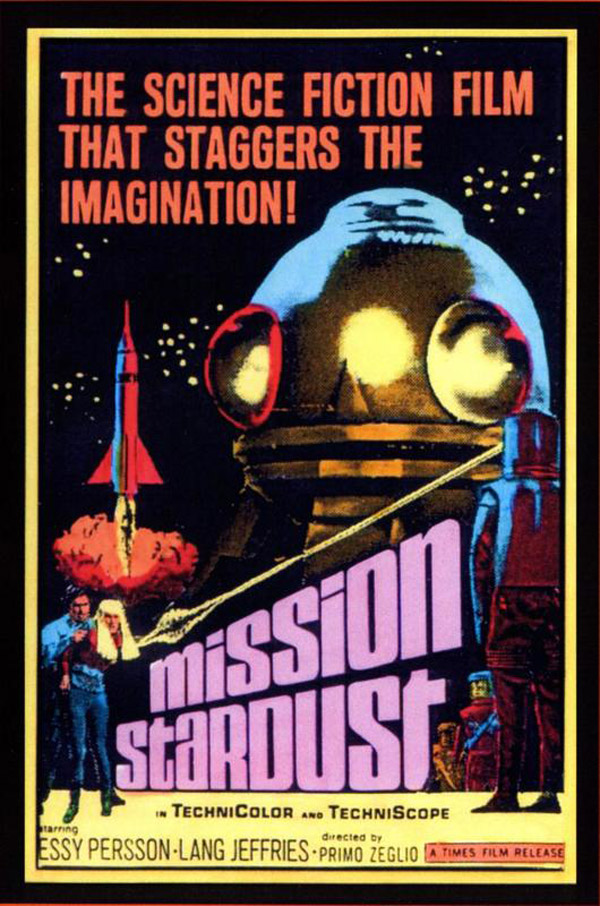

‘Mission Stardust’ (1967)

IMDB metadata: 1 hour and 37 minutes @ 3.9 from 479 friends of the producer.

Half Sy Fy and half an ersatz James Bond thriller from Italy.

‘Staggering?’ No more like numbing.

‘Staggering?’ No more like numbing.

The first Earth flight lands on the Moon, and its four-man crew sets out to do some science, collect samples, survey, map, and gawk at Terra. (They do not light up.) But they are not alone!

There is another ship, a round June bug with external retracting landing gear. The fraternity brothers thought it was cute, more so later when it gave birth.

The June bug on the Moon.

The June bug on the Moon.

After a standoff, two of the Terrans meet the aliens who are as insecure as Ivy League graduates who have to tell everyone immediately and repeatedly that they are Ivy League graduates, and boast again and again about their superiority to the Earthlings. Superior, maybe, but tactful not. The chief proclaimer is a chump-cha Twiggy in a platinum wig. In addition there is a wise old owl, and robot who seems nicer than Twiggy and smarter looking than the wise owl. Pretty sure that wig was used again later in ‘Sette uomini d’oro nello spazio’ or ‘Star Odyssey’ (1979) without Twiggy underneath.

‘Superior,’ did she say, time after time, and yet they can’t change a tire on the spaceship, which is why it is stuck on the Moon waiting for some road service retards from Earth to wander by. How superior is that! The Terrans volunteer to change the tire, while Twiggy repeats the scriptwriters mantra. Owl gets all faintly and the Terra doctor notices he has leukaemia. Tire changing will do that.

Twiggy and the Earthmen join….forces to treat the disease in the owl. Because they are so superior the aliens have neither a doctor nor medicine. Did she say superior? Well maybe it is a superior form of leuekmia, which the fraternity brothers thought mainly afflicted the young. Mr Owl is no spring owl.

Best treatment for leukaemia on Earth is to be had in Mombassa. Mom bosa? In Kenya. Sure.

The big June bug ejects a mini June bug and an away mission to land in east Africa. Twiggy brings along one of the really big-button remoters for geriatrics just in case. Superior technology, not! It gets put to good use.

The wise old owl goes on about the union of the two peoples of Earth and owls. The fraternity brother responded to that idea with enthusiasm.

There we switch to James Bond, complete with a villain sporting mirror-shined loafers and stroking a hairy pet. Blofeld slumming. Another wanna-be villain.

It’s like this. The Superior Beings with a flat spaceship tire and leukimea have a stash of diamonds. Blofeld knows this because one of the four Earthmen contacted him to rat it out. (Disclosure statement, I fast-forwarded past this revelation, so that is my interpretation based on what happens next.) Blofeld also knows that they are going to the clinic so he plants his killer nurses there with Uzis up their… It’s a trap!

Earlier the army had wasted screen time trying to blow up the ship, the robot, and the director’s chair. Something. Anything.

Later there is confrontation and shoot out on the Moon. The traitor gets it. Blofield gets it. Twiggy gets it.

Union at last. The end.

Union at last. The end.

Never seen anything quite like it. It is a genre mongrel, part drive-in Sy FY and part low-budget James Bond. There are other mongrels in the Sy FY kennel, usually noir thrillers like ‘The Atomic Man’ or ‘The Amazing Transparent Man’ and others that blend with musicals, krimis, ghost stories, and …..

The levitation effects were fun. The robot unmasking was neat. The June bugs large and small were cute. It must have used everyone in Kenya as an extra.

But, really, 3.9 seems high.

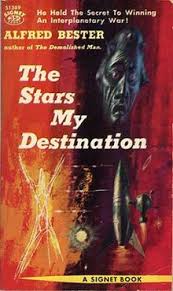

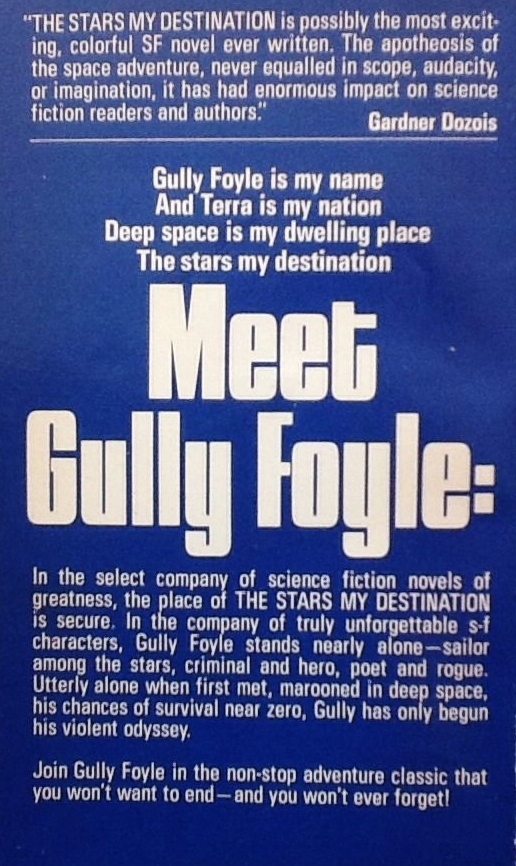

‘The Stars, My Destination’ (1956) by Alfred Bester

A bildungsroman of sorts as Gully Foyle grows and changes with his experiences, and the greatest changes occur at the instruction of women. The first is the one-way telepathic black woman whom he rapes and, in a way, sets free. Later they form a team of convenience. The second is Jiz whose influence on him is considerable, making him grow and change. Finally is the White Icicle who attracts and repels him in equal measure. Least influential but last is Moira, the stay at home.

Gully begins the story as an uneducated barely verbal spaceship hand on the Nomad. Think of the channel 7Mate demographic without the drooling and scratching and you have him. By the end he is richer than all the cynics who own Channel 7Mate put together.

The Nomad is a wreck floating in space and Gully alone has survived the attack by dumb luck and a resourcefulness he did not know he had. A friendly spaceship hoves into view and he signals it, quickly and repeatedly. Yet it passes him by, contrary to all the laws, rules, norms, and ethics of spaceflight.

Thereafter he swears revenge on that ship. Driven by that desire he survives, and later prospers, and learns, and seeks the guilty ship. The adventures are many, the plot twists are deft, the characters differentiated, the settings detailed and followed through, and the science fiction is etched into the story and the characters.

The first, and as it turns out, the last key, to the narrative is that in this world of 2550 teleportation is as common as walking is today. To move from one place to another one teleports oneself, clothes included and anything one is carrying or holding. Distance varies with ability and practice. It is safer than walking since there are no crazed drivers on King Street to dodge. The method is a mental discipline developed by a Mr. Jaunte, and so it is ‘to jaunte.’ The telekinesis involved is crucial to the narrative and the denouement.

There are three treasures in this quest. First is a vast fortune of Credits 20 billion, where a hundred credits is a great deal of money. Second is a rare mineral that releases vast quantities of energy, far exceeding uranium and its mutant cousins. Third is Foyle himself, much to his own surprise, and to the reader, too.

There is much satire of the super rich, so much it grew tedious to read, but it is fitted to the overall plot like a jewel in a ring. In a world where movement is by thought conspicuous consumption to signal one’s riches becomes conspicuous transportation.

Nicely embedded in that satire is Foyle’s hiding in plain sight for a part of the time, as the most ostentatious and conspicuous transportee, while he seeks leads to the hated ship. Although his choice of an alias was a quick and certain give away it took the villains a long time to figure it out.

There are also a couple of surprising passages for a 1956 publication about the role of women in this wealthy society, sequestered, hidden, and rather like pets in a zoo. None of that applies to the first three women whom he encounters, though the last one is of that sort of society. Finally he returns to Moria as we all do. One is an illegal immigrant and the second a convict.

Without any explicit comment, Bester also shows a society with deep, very deep class divisions so that members of the working class where Foyle started, are barely educated, civilised just enough to do a job like living machines. Indeed he is so dense that at first the target for his vengeance is the spaceship itself. Only later does understand that the crew made the decision and then he targets them, but in time the realises that the captain gave the order.

There is no preaching by the author but the reader gets that point. So much Sy Fy is spoiled by childish preaching by the author using the keyboard as if it were a sledgehammer to drive points home to the dense reader all too much like the morons on Fox News yelling at the camera.

Alfred Bester

Alfred Bester

Another flaw that has stopped me reading a few Sy Fy titles is the ostentatious erudition that some author parade to show how clever they are, like the pointless CGI of so many movies, but which advances neither plot nor character. This title is free of that egomania.

That it opens with an excerpt from William Blake’s most famous poem which is integrated into both plot and character.

I read it in an adolescent Sy Fy phase but had forgotten all the details.

By the by, holding physical objects accountable for the consequences arising from them may seem absurd to us — we know the spaceship itself did nothing — but Athenians did not. A building block that fell and killed some would be tried, sentenced, and smashed.

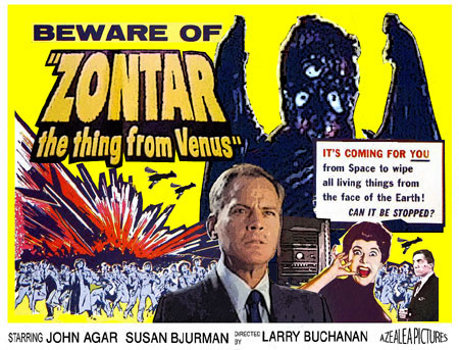

‘Zontar: The Thing from Venus’ (1966)

IMDb Metadata 1 hour and 20 minutes of Dali Time, rated 3.0/10 by 670 time wasters.

‘It Conquered the World’ (1956) was Zontar’s first effort at Terra domination. But Zontar had a sibling and here it is. Sexing Venusians is beyond even the fraternity brothers, so we will leave it at ‘It.’

The Dallas production company copied ‘It Conquered the World’ nearly line by line and scene by scene, except at the coda. It is not a continuation of the previous story but a tired and trite repetition of it. The plagiarism is so literal that it even includes the same 1950s ethnic accents for some of the most minor characters. However, the decor, fashions, hair are all of the 1960s.

John Agar, about whom more below, saves the world once again, single-handedly as he prefers. This is done after his wife and his friend try to kill him. Macho Man that he is, he kills his wife, but bonds with his friend. Is this man-love?

The acting is uniformly wooden. Agar is the exception; he is robotic: stiff and mechanical.

Copied yes, but the homily at the end differs. Most Sy Fy films have some kind of coda. At the end of ‘It Conquered the World’ Peter Graves told audiences that humanity would prevail because humans have feelings, emotions, compassion,…. [ad nauseam]. In this outing, Agar’s text does not celebrate all that girly New Testament stuff, but declares humanity will endure because we think, reason, do science, and such. Hooray! Banned in anti-Vaxxer states across the nation.

That pulled me up short. While ‘It Conquered the World’ is a better movie, this is a better message.

‘It Conquered the World’ is a better movie at 4.9 on the IMDB opinionmeter, though in the basement, because it has much more energy, vitality, momentum, and tension than this leaden exercise.

Once again John Agar’s (1921–2002) feet do not touch career bottom. He kept it up for nearly another forty years! For a man who was second to John Wayne in ‘Fort Apache’ (1948), ’She Wore a Yellow Ribbon’ (1949), and ‘Sands of Iwo Jima’ (1949) this is a long way down. After marrying America’s sweetheart, Shirley Temple, he found a greater love in the bottom of innumerable bottles of alcohol, so the story goes, and that love ended his marriage and put dent in his career.

The titles indicate the substance of this selection of his oeuvre.

‘Revenge of the Creature’ (1955)

‘Tarantula’ (1956)

‘The Mole People’ (1956)

‘Daughter of Dr Jekyll’ (1957)

‘The Brain from Planet Arous’ (1957)

‘Attack fo the Puppet People’ (1958)

‘Journey to the Seventh Planet’ (1962)

‘Women of the Prehistoric Planet’ (1966)

‘Curse of the Swamp Creature’ (1966)

In most of them he played an authority figure, a scientist or an army officer, something he never was.

That career came as a result of his marriage. After he married Temple, her studio hired him, put him through acting school, and cast him in his first film, ‘Fort Apache.’ When she divorced him friends like John Wayne tried to help him with work but the shambles continued. Despite it all he kept acting, in his way, when not in jail for drunk driving, assault, harassment, stalking, petty theft, and such, yet he has a long list of roles on the IMDb, the last released in 2005 after his death. He is another Hollywood high diver. Started out on top and plunged to the bottom in no time at all.

According to the cinema oracle, IMDb, there is a Zontar Television series. Tempting….