It had to happen sooner or later. Lord Peter Wimsey has become the Duke of Denver, upon the death of his older brother Gerald. That dukes are higher than lords is news to me.

With the title Duke comes ducal responsibilities, most of which were new to Peter Wimsey. There are vexatious relatives, disputatious tenants, ravenous charities, clogged drains in the strangest places, a crumbling pile that is crumble still, elderly retainers to retain, so that when he is called to Oxford, off he goes! What a relief!

When he was but a lord, to him the relatives were polite, the tenants deferential, the charities distant, the drains unknown, the ancestral pile was for holidays, and the retainers retained. As duke, it all changed.

Called to Oxford? One of the Duke of Denver’s entailments is to be The Visitor to a not very distinguished college at Oxford. While every other Oxford college Visitor is a royal of one magnitude of another, this college has the Duke of Denver. Investigation in the muniments room of the aforementioned crumbling pile reveals that generations ago a Duke of Denver handed over some dosh to replace a roof or two at the college and in return for that largesse the title The Visitor was bestowed upon him for his lifetime, but in a subsequent change of the college constitution the limitations ‘his lifetime’ was omitted, perhaps by error.

Well, no matter, an escape to Oxford is most welcome for the poetry quoting, incunabula collecting, Saxon speaking Wimsey. It is a return to lost youth for this old soldier.

Peter is now married to Harriet (née Vane) and it seems to be after World War II and in the early 1950s. The stately home is crumbling in part because of a fire caused by an errant German bomb and taxation is vexing.

Together they descend on the college to find themselves in the middle of an acrimonious and bitter conflict among the twenty of so fellows of the college over the status of a tenth century book in its library. The conflict is so vitriolic that no one speaks of it! Immediately I found this scenario easy to believe.

These scholars seem to do little else but plot one against another, while seldom is heard a discouraging word from their lips. Backstabbing, undermining, poisonous rumours, slanderous gossip, attribution of venal motives, all communicated by innuendo and sotto voce, these are the weapons of choice. Meanwhile, at high table meals the weather is much discussed. This is brutal realism at its best.

Even the engineers and economists among the brethren have taken sides over this book. On the one hand, the goal is to sell the book to raise money for yet another roof and on the other hand is the over-our-dead-bodies group! Yep, prophecy there.

Each fellow votes in a time honoured, and otherwise incomprehensible, arcane ritual and each poll results in a tie. After three such votes, some of the parties invoke the right to summon The Visitor to adjudicate. Enter the Duke!

While the vote remained tied in those three rounds, the constituency shrank. The senior most fellow, the Warden, went missing and another died falling down stairs. Two others had unlikely accidents, which while damaging, were not fatal, but which precluded participation in the voting ritual. In the best tradition of krimis the ritual does not admit of absentee or proxy voting. Is someone mowing down the voters? Are there two mowers, one on each side of the question, the keepers and the sellers? Are there only two sides to the issue?

Before any Solomonic adjudication can occur there must be sleuthing to find out what is going on.

Harriet takes no convincing to join in, and engages her own distaff Oxford network, and the ever reliable Bunter mines the college servants with his usual dexterity.

Nothing is what it seems to be.

As in C.P. Snow’s Cambridge novels, all of which I have read [Groan!], the scholars do little scholarship but make an enormous fuss over the rituals and prerogatives that fall to them, like passing the port. It is all too credible.

Dorothy Sayers created Wimsey in the 1920s.

While Ian Carmichael brought him to life on the small screen in the 1970s.

Ian Carmichael as Peter Wimsey

Ian Carmichael as Peter Wimsey

Bunter was an older man, and he and Wimsey had been through trench warfare in Flanders together and had survived, thereafter bonded for life, and with a considerable amount of unspoken communication.

Despite the dreadful experience of Flanders, Wimsey (and for that matter, Bunter, too) remains Edwardian in manner and morēs. Wimsey is an enthusiastic and effete dilettante, who quotes obscure poems in dead languages and playwrights unknown all the day long while playing the piano and sporting a monocle. His private collection of incunabula is the envy of museums. His flow of witty banter is without end and without purpose. Noel Coward could not have bettered him as a caricature.

Bunter unfailingly addresses him by his title and always stands in his presence. Always and always. Bunter out butlers even that fellow James Stevens in ‘Remains of the Day’ (1989).

Harriet, mindful of her own modest origins, tries after a fashion to loosen them both up, with little success. Nor does she seem aware of the changing times of the 1950s.

The unalloyed Edwardians Wimsey and Bunter are an odd couple in world of a Labour government and many new social attitudes. Still that is part of the fun.

Like Sherlock Holmes and more recently Hercule Poirot, Wimsey has his re-animators. This is the fourth title by Paton and I have liked it enough to read another. Though I did find it wordy, but Peter is like that. There is much talk, often about nothing much, and too little detection. It must be struggle to be arch and witty when talking about staircases and fence posts, but Wimsey is made to do it. Poor fellow.

Jill Paton Walsh

Jill Paton Walsh

He even indulges in the future subjunctive interrogative at times, such is his mastery of all things Fowler. (Mortimer, skip it. It would take too long to explain.)

Even in the sleepy village I know well, the absence of the senior scholar for three months would be noticed and some effort made to figure how what happened to the missing savant lest the key performance indicators be spoiled.

‘The Treasure of Saint Lazare’ (2014) by John Pearce

Our hero, Eddie Grant, he of the chiseled jaw, martial arts belts, multi-lingual talents, and accomplished lady killer …. [Is there nothing beyond him?]

The set up is this. Ed (I refuse to call a grown man with such a cv as above Eddie) is the son of World War II veteran whose assignment in 1944-1946 was tracking down art looted by Nazis. His father died earlier, in suspicious circumstances that Ed mentions but apparently was not motivated to do anything about at the time. Then the father’s assistant from the wartime assignment dies, again in suspicious circumstances. This assistant left a letter to Ed’s father, not knowing he had predeceased him, and asked that his executor deliver it by hand.

Since the dad is dead the messenger, a daughter, delivers it to Ed. She is of course a beautiful woman who falls under Ed’s spell, taking her place in the queue.

It just so happens that Ed has many contacts in the worlds of policing and art, and these he now mobilises. Why he did not mobilise them when his father died is unknown. Even more mysterious is why he did not mobilise them when his wife and child were murdered after his father’s mysterious death. All of this death is supposed to awaken sympathy I suppose but it just makes Ed seem a jinx and jerk. Four dead before he goes into action.

Then the big black Mercedes limousine appears bearing — as it must — Germans.

So much for subtlety. The plot is by the numbers and the characterisation are connect the dots.

I quit at about 25% on the Kindle. I was reading topic sentences only and flipping on; it was time to move on.

At the start there is much too much backstory forced into the opening pages so that we may appreciate Ed, followed later by extensive and pointless descriptions of hairstyles. clothing, drinks, furnishings, cars, and so on and on. This later I guess is the Paris part. If this superfluous detail were cut to the standard say of Georges Simenon the text would reduce by more than two-thirds. Good grief. Amid all the bland descriptions there is very little story. With John Stuart Mill, I suppose that we know a person by deeds not by the recitation of a backstory. What do I care about the backstory until there is a front story?

Nor is it possible to warm to Ed for whom everything seems to come easily though he moans and groans about it.

This is described as ‘a novel of Paris’ and I wanted to test that proposition. There is much Paris in the early going and I consulted by Michelin map, but then we head off to Orlando in Florida and…. I supposed it gets back to Paris but without me. The Florida trip seems mostly to be an occasion for more pointless description.

After re-reading all of Iain Pears krimis with Jonathan Argyll and Flavia di Stefano chasing lost paintings the reference to a lost Raphael was intriguing, but this treatment is not arresting for this reader.

I had a look at the comments on Good Reads to see what I was missing. I looked at the effusive ones, further confirmation that this source is not credible.

John Pearce

John Pearce

Speaking of sources without credibility, one of the local rags has a weekend feature called something like ‘Books that made me’ in which minor celebrities, well I guess they are but they are unknown to me, list and comment, briefly, on five books that had a formative impact of their being. Nice idea, but the execution is kindergarten.

These celebrities seem not to do much reading and certainly not of, say, a novel of consequence or a historical study of insight. Instead we have excited drivel over self-help manuals, diet plans, children’s books – see I said kindergarten – and Mills and Boon stories, Alice’s adventures. In some cases it is pretty clear it was a stretch for the subject to think of five books. When one of these pieces refers to ‘Death in Venice,’ ‘Swann’s Way,’ ‘Absalom, Absalom,’ ‘The Iliad,’ ‘Crime and Punishment,’ ‘Hotel Baltimore’ and their kind, let me know.

‘Mega-Headaches’ by Bent Flyvbjerg

‘Australian Financial Review’ of 28 July 2017.

Why is it that large projects continue to be undertaken and to repeat the same mistakes of all those which went before them, that is the question? Flyvbjerg explains the recurrent attraction of mega-projects along four intersecting and interacting vectors: they are technological challenges, they are politically attractive, they create a constituency of profiteers, and they are aesthetic.

Mega-projects by definition have not been done before and so engineers, designers, builders, technologists, find them stimulating, ready and willing to give it a try. Look at the sails of the Sydney Opera House, and remember they were made and fitted by hand, long before lasers.

The political attraction is in the grand project that will define an administration, or even an era. Think of the those pyramids in Ghiza.

The profiteers are the facilitators, the bankers, consultants, fixers, the lobbyists, financiers, and all those others in the middle, who do not build anything but without whom nothing can be built. Then there are the builders themselves, the construction firms and their employees, and their insurers and suppliers. ‘Profiteers’ is my word, not his.

Finally, there is the aesthetic dimensions anticipated in the completed project by designers, artists, and users.

Despite all of this impetus many, many mega-project go awry. Before getting to that, a few definitions. A mega-project is big, over a one billion USA dollars. For examples, in addition to those passed by above, consider the Canadian Firearms Registry, the Big Dig in Boston, Channel Tunnel, Viaduc de Millau, Lake Pontchartrain Causeway, North Sea Protection Works in the Netherlands, and that black airport in Montreal, Mirabel.

The most common failure of such projects is cost overruns, some of which are truly astonishing, like the Sydney Opera House that came in — sit down, Mortimer— 1,400% over budget in real terms.

The second most common failure is missing the target completion deadline and running on and on, and here I think of another example close to home, though it may not have hit the billion dollar price tag, the OPAL public transport card system, a three-year project that took fifteen years before the first tap. (OPAL users will get it.)

The third most common failure is to return the benefits asserted for the project. Investors lose a lot of other people’s money in mega-projects, even in the private sector, e.g., the Chunnel. Every rider on EuroStar is still being subsided by the financiers who invested the pension funds they manage into that hole under the water while paying each other six-figure bonuses for their wit.

With these failures, other matters recede, but there are also failures regarding the environmental impact of mega-projects. Is it any wonder that the public is cynical about the projections and promises made?

The failures are so numerous and catastrophic that one wonders why we keep doing it. It certainly undermines confidence in the financial projections, the pace of construction, that management of labour, the environmental impact assessments, projected use and earnings, the alleged rate of return on investment, not solving the problem the project was supposed to solve, and more. The litany of such failures makes fascinating, if morbid reading.

Yet this reader wondered if that was the whole story. Impressive though the data in Flyvbjerg’s study is, much has been omitted. For a start the study concerns only failures, and not successes, and there is a long list of mega-projects on Wikipedia that seem to be successes, again including some close to home like the desalination plants in New South Wales and Victoria which proceeded so smoothly no journalist could make up a story about either of them. The unerring eye of hindsight on display in this account is like Barbara Tuchman’s successful but superficial ‘The March of Folly’ (1984).

What foresight distinguishes successful mega-projects from unsuccessful ones? No enlightenment comes from this account.

Flyvbjerg also omits one crucial constituency in his rather jaded four part explanation: The public. When commenting on the political attraction of mega-projects and the interest of the profiteers, Flyvbjerg’s explanation is cynical self-interest. That is why I used the work ‘profiteers.’ Hmm. Doubtless a factor, but generative or decisive?

What is the political benefit from the colossal failure? If failure is so likely, why take the risk? Maybe that caution explains the long delays with the Opal Card.

Those who stand to profit may also have more complex motivations about the challenges and competitive opportunities. Ready as I am to disparage others, preferably those about whom I know nothing, I reserve judgement on this.

There is a missing player in the epic of mega-projects and that is the general public. The mega-project can create, stimulate, and capture the public imagination which the media then reflects and amplifies. It would be a brave political leader, pension fund manager, or designer, to reject the public pressure that can be conjured for such projects. Another local example was the millennial Orange Grove project in Sydney that had a considerable popular following. A state government minister who rejected that development because of skepticism about the projections would have be crucified by the same journalists who lit the fires when the project fell.

The public is missing in another respect, as an opponent of some mega-projects. Surely one reason for the costs of the Big Dig in Boston was sustained and calculated strategic and tactical opposition of several publics. The bill for the litigation must have been enormous. Indeed public opposition has stymied many mega-projects, e.g., a third Sydney airport.

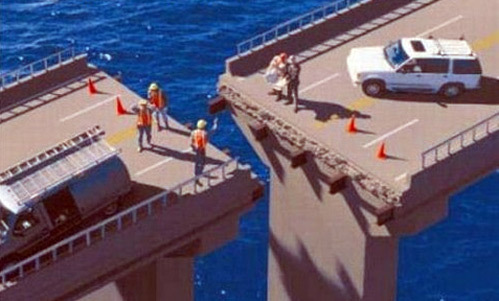

Bridge-building Italian style.

Bridge-building Italian style.

In this short newspaper reprint Flyvbjerg omits that recurrent five-ring circus of the Olympics which illustrate the popularity of mega-projects regardless of the cost over-runs. Olympic bids are wildly popular and hosting the Olympics is even more popular to all, but the die-hard spoilsports like me. One of the masterminds of the Sydney Olympics once privately said it was worth the money for the lift it gave to public awareness and pride.

Nor does this analysis include defence projects or military planning where there are many failures to be sure, but there have also been some spectacular success in projects the complexity of which dwarf even the largest mega-projects. Note that NASA did put astronauts on the moon and bring them back. These examples suggests plans and forecasts can work. Why sometimes and not others?

Defence projects are legendary for cost over-runs and that is as true in Australia as anywhere else. Those Collins Class submarines are an object lesson, and I hope PhD students are examining the details. In order to mobilise the public support to spend money on competitive submarines, the government had to insure that the boats were built in Australia and that the work was spread around the country, so that there was an informal coalition of parliamentarians and community groups who supported the project because of the money to be spent in their electorates. None of that is cost efficient in the short term, and probably not in the longer term. But it is political necessity. Ditto the financing has to be distributed to create support.

A Collins class submarine in Sydney Harbour

A Collins class submarine in Sydney Harbour

At a formal dinner once I sat next to a Royal Australian Navy officer who was in submarines, and inevitably I asked him about the Collins submarines. He had a lot to say about how excellent they were, but when I asked him about the cost over-runs and missed completion dates, he said that it always happens. [Pause.]

If so, then why were not such costs and delays built into the original planning, just as the builder who did our kitchen had an allowance for extras in money and time to cover the unforeseen? If foreseen, then why not integrate an allowance for the unexpected into the process? That was my question. His line by the way was the official navy line at the time as subsequent research showed. ‘No big deal, it always happens.’ If so….!

Much of the four sublimes, as Flyvbjerg calls them, are generated, empowered, and enabled by the public appetite for such projects, and according to the fount, Wikipedia, many are in fact successful. That term ‘sublimes’ grates on this reader. It seems forced and uninformative.

No doubt in the full text of the studies Flyvbjerg has done of the massive data set he has complied with care and wit such niggles are resolved.

Bent Flyvbjerg

Bent Flyvbjerg

While this article was in a newspaper this week, I read virtually the same text in 2014. Slow news takes on a new meaning.

For years Bent Flyvbjerg’s book ‘Rationality and Power‘ (1999) held pride of place on the syllabus. The abstract title came down the the ground with a thump in the study of the building of a bus terminal in Aalburg, Denmark.* What a story! What a story-teller! Altogether it was what social science should be but seldom is, wise, contextualized, plain spoken, dispassionate, located within major intellectual currents, and modest. This study also shows the public enthusiasm for such projects and the distortion of the original project necessary to achieve a coalition to realise it. By the time all of the interests which wanted a piece of the project got it, it was distorted beyond recognition.

That was democracy at work, not dastardly financiers, unscrupulous politicians, air headed aesthetes, or pastry faced tech heads.

*Many travelling students sent me pictures of the bus terminal at the heart of this study, for which much thanks.

Arnaldur Indridason, ‘The Shadow District’ (2017)

A krimi set in wartime Reykjavik Iceland in 1944. The island is awash with soldiers and sailors of the Allied forces: Brits, Canadians, French, and mostly Americans. Harbours are dredged, piers built, fuel tanks dug into hillsides, pipelines laid, barracks built everywhere, landing fields levelled, hangers erected, roads paved, concrete bunkers made, ammunition dumps created, and on and on, from 1940. There has been more money spent on the island in those five years than in the previous five hundred years.

With so much money comes loose morals, it would seem, despite the language barriers. While Icelandic men are not off at the war, they are off on construction jobs all over the island, leaving wives, sisters, cousins, and daughters to their own (de)vices.

The setting and the set-up are good. On the plus side is some detail about the impact of this intrusion on Iceland, and not just the sex, but also on nationalism, though that is merely mentioned and not in any way developed. The weather is there, too, but it does not figure in the story, as it did in ‘Trapped.’ There is also a little more about Iceland legends, the hidden people, but again it is a sidebar that is not cemented into the plot.

The execution is not equal to the set-up. First, the story is split between then in 1944 and now in 2000, say. This is a technique I cannot abide because it makes the reader responsible for integration. Second much of both stories, the then and the now, is padding, e.g,

‘I walked up the the three plank steps to the door. I took off my left glove and knocked on the door, and waited, while I put the glove back on. I heard faint sounds insider but the door did not open.

I took my glove off again and knocked on the door again. I put the glove on and waited. And waited.

The door opened. I introduced myself and asked to come in for a word. She said, no. I asked gain very politely. she said no and turned away. I asked once more for a word inside. She said alright.’

Snappy, uh? He then asks her what she saw. She says she saw nothing. He asks her three times and three times she says she saw nothing. Bold, he asks a fourth time, again no result. He leaves, descending the plank steps.

That took about five pages for nothing. He then repeats most of this verbatim to his partner over the next two pages.

While this book is slow, it is not detailed, but rather superficial. Two examples suffice. (1) The Icelandic nationalism is mentioned more than once but never articulated. (2) While there are many soldiers around there is never anything about their role in the war effort or how Icelanders feel about being occupied. Is this war their war? They are, after all, eddas or not, Danes by blood and the German heel is on Denmark, yet that is never even referred to as an issue in the story.

The text, perhaps thanks to the translator, is replete with banalities. If there was a clichéd way to say something, that was the way it was said.

Arnaldur Indridason

Arnaldur Indridason

This is one industrious writer who has three series, the one that includes this title is Reykjavik during World War II, including ‘Silence of the Grave’ (2007), which was adequate, and another series that follows the investigators of Inspector Erlendur, e.g., ‘Jar City’ (2007) which I liked a lot for its meticulous attention to detail, especially in thinking things through. Erlendur as I recall does a lot of thinking. In contrast is the author’s third series ‘Reykjavik Thrillers.’ On the strength of Erlendur I read his ‘Operation Napoleon’ (2012) and regretted it and did not bother to finish it. The list of his titles on Amazon translated into English is long,

While my recollection of Erlendur is strong enough for me to try another, from now on I will pass on the other two serieses.

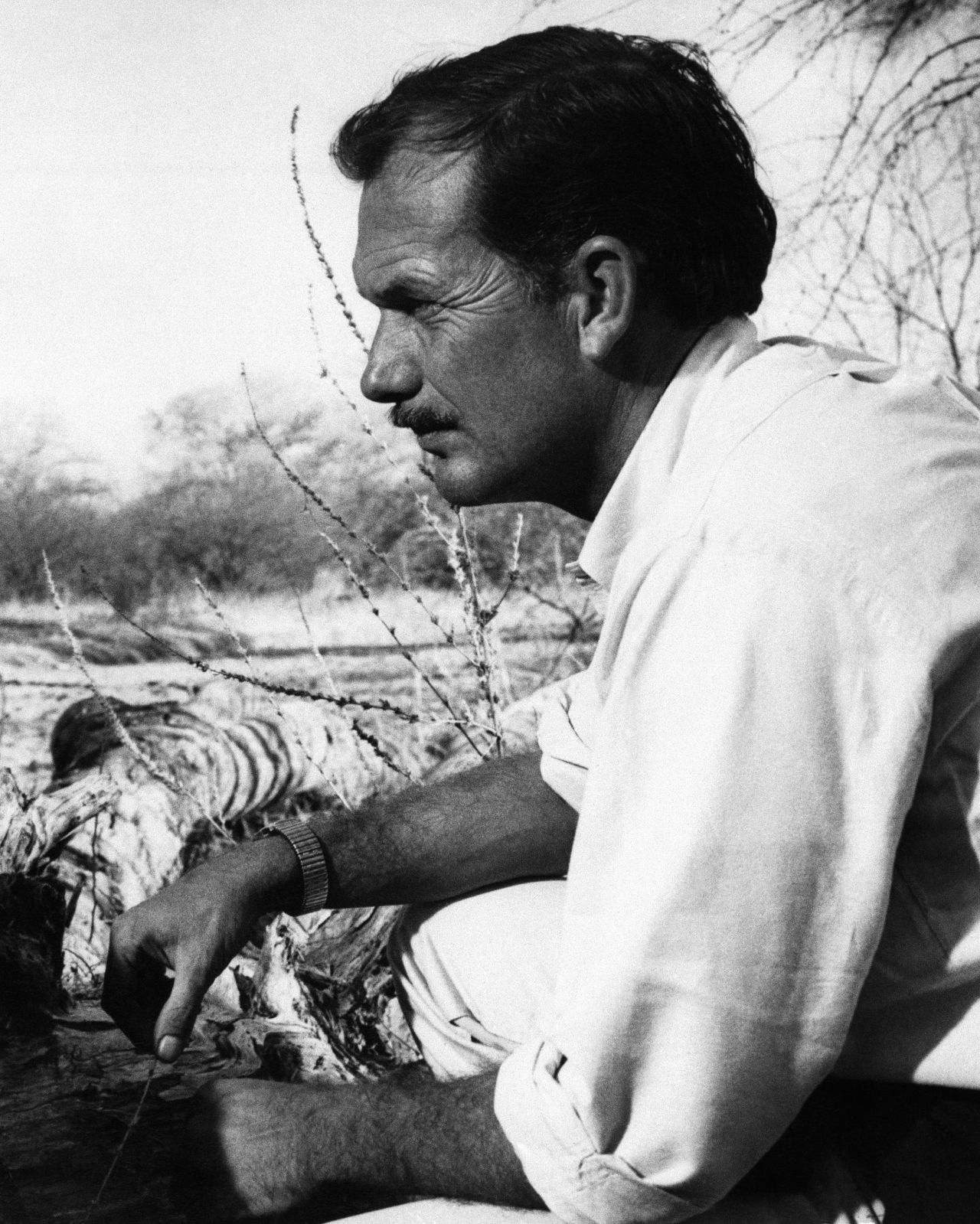

‘Ride the High Country’ (1962)

One of the great westerns. It combines a young director with two of the wisest hands on the ranch. Randolph Scott and Joel McCrea between them must have been in more than a hundred and fifty oaters. McCrea made it a point only to accept roles in Westerns and Scott did virtually the same thing though less explicitly. I would like to think that they did so for the same reasons that Justin Playfair gives in ‘They Might be Giants’ for only watching western movies. See the review of this latter film elsewhere on this blog for further explanation.

A publicity photograph.

A publicity photograph.

Two ageing lawmen find the west has changed and so have they. It is no longer in need of them. One has become a sideshow barker and the other a bar-room bouncer. Then a job comes up, one with a modest reward but it smacks of the old days and the old ways, off they go once again a team. One is losing his sight and other has arthritis but this is too good an opportunity to miss….for one of them it offers vindication and for the other one it offers something more venal.

In 1962 audiences were also changing and the Western was on the way out. Nor was there any further need in Hollywood for these two old actors in particular. The screenplay reflects their own situation, too. It becomes a story about the actors as well as the characters they embody.

The tattered McCrea remains steadfast, but the flamboyant Scott has heard a different drum, after countless brawls, wounds, ambushes, shoot outs, injuries, chases, beatings, falls, and betrayals it is time to taste the honey. With what he thinks is subtlety Scott tries to suborn McCrea who seems not to realise what is going on. Subplots add depth and as in every Peckinpah film, each character however minor has a name. Edgar Buchanan’s brief speech at the wedding, Federico Fellini could not have done better, gave me pause for thought.

Sam Peckinpah

Sam Peckinpah

The Biblical reference to ‘entering the house justified’ is another gem.* Any close observer of Peckinpah’s films will realise, he was student of the Bible and studded his films with imagery and lines from parables, hymns, letters, psalms, and words of the prophets.

The landscape of the high country is an elegy to a cleaner, better world made foul by humanity at its worst.

Then the denouement comes. Perfect. The exchange of looks between McCrea and Scott constitute a master class in acting in a few seconds. Each man sums up his own celluloid career in a single glance.

The end.

The end.

Then there is that last line of dialogue delivered by McCrea as his sun sets. Moving and marvellous. Redemption is even sweeter than honey.

*Luke, 18:14

‘Death of Delos’ (2017) by Gary Corby

Love this series of krimis set in the Athens of Pericles. Nico and Diotima set sail for Delos for she has been chosen to represent her temple at a ceremony on Delos. Indeed it seems the goddess Artemis has chosen her, for her name was picked twice out of an urn. Twice?

The first time her name emerged on a pottery shard from an urn it was rejected and replaced. Why? Because it is not suitable for her to go, being so heavily pregnant. Huh? It is forbidden by Zeus for anyone to die or to be born on the sacred island of Delos. Why did Zeus lay down this law? Because the island was the birth place of Apollo and Artemis, the golden twins, and there shall be no further births there, and a death would desecrate the place.

But when her name came our once again, after a great deal of urn shaking, the priestesses recognised the divine will and off she went, taking husband Nico in tow. All in all a two week jaunt to the Greek islands in high summer seemed like a good idea to escape the heat, humidity, dust, and pressures of Athens, and while Diotima is pregnant there is plenty of time because the ceremony on Delos is but one day and then they can move on to Mykonos for a vacation, and perhaps even the birth of the next generation. What can go wrong?

Ah huh.

While they sail in a gold encrusted ship with a polyglot crew devoted to such ceremonial voyages it is, strangely, accompanied by a fleet of fifty, count ‘em, Athenian navy triremes in war paint, i.e., black.

Delos is marked by the red star.

Delos is marked by the red star.

Just before sailing the hapless Nico was summoned to the great man’s presence and given the word. The great man is Pericles who has made Nico his catspaw for discreet work here and there, often involving the detection of whodunit. Nico can hardly say ‘No!’ to the first man of Athens, as much as he would like to do so, especially this time.

Pericles tells Nico that he — Pericles — will be coming along in those warships, because even then Athens was outspending its Euros and needed some more readies. Readers of ancient history know this sad story, and in Thucydides’s ‘History of the Peloponnesian War’ it stands as an early sign of Athenian corruption. The Athenians have come to steal the treasury of the Delian League (147 members) kept on the sacred island, held in trust by the highest of high priests and priestesses of Apollo and Artemis. The Athenians come armed and ready to take it, if it is not given by the religious guardians. Though what a few hundred clerics and another few hundreds shepherds could do in the face of an onslaught of Athenian marines is not much.

But will the marines risk their immortal souls at the order of Pericles to seize the treasure? He would rather not find out, and so — as always — he tried to talk the highest of the high priests out of the treasure. Pericles is at his glib best and has a smooth and convincing reply to every protest, he thinks. While the formally designated highest most high priest wavers in the face of Pericles’s sophistry, one old curmudgeon does not. Gero is his name and he knows right from wrong whatever Squid Head says, as the irreverent called Pericles for the elongated shape of his head. (Being sensitive to this indication of his alien origin, Pericles almost always wore some kind of hat.)

A standoff ensues. It is for such occasions that Pericles has a confidential agent at hand, one Nico. Gulp! Diotima is firmly on the side of the gods on this one, and she and Nico have words, while he fusses around her with fans and water to keep her and her passenger comfortable.

There were once twelve of these lions protecting the temple.

There were once twelve of these lions protecting the temple.

These are charming stories, this being the seventh, in a series that remains fresh and vivid. Corby continues to mine the historical record for frying pans and fires into to which to sauté Nico and Diotima so that readers can watch them squirm, and squirm they do. While Pericles appoints Nico to suborn Gero, the Highest Priest appoints Diotima to see that no suborning occurs! Well, not quite but close enough.

The plot gets thicker when Gero is found dead with a sacrificial knife in his heart! Whodunit, indeed? A thorough investigation of the treasures and treasuries on Delos reveals….. [Think Enron, think Lehman Bros, think…]

Hardened readers of police procedurals know what is coming next, and it does.

Gary Corby

Gary Corby

I ordered this for the Kindle before it was published and awaited its appearance, then one night after finishing a heavy-duty krimi it appeared in my Kindle Library as if by magic. It was a magic powered by American Express and Amazon in combination. I was delighted and devoured the first chapter that night, despite the alarm set for 6 a.m. the next morning to welcome the builders come to rip out the kitchen and rebuild a Star Trek galley complete with replicator. Power tools at 7 a.m. get the day off to a good start.

All is revealed about the Delian League on Wikipedia. When Pericles came calling in 451 BC the heavy handed Athenian treatment of the League had made it into the Athenian Empire. Previously independent member states like Naxos and Thasos had been coerced, and the tax levy was set to fund the building program on the Acropolis, not to intimidate the Persians. That Pericles might prefer an empire to a committee meeting of 147 members does make a lot of sense.

‘The Night People’ (1954)

A very cold Cold War film noir set in the Berlin of 1953, just after the Korean War. Everyone is on edge. The military presence — USA, Great Britain, Soviet Union, and France — in Berlin is considerable. Is there going to be a European encore for the Korean War there in Berlin?

Gregory Peck is in US counter-intelligence, trying to extract a Soviet defector when he is lumbered with the kidnapping of an American soldier, a private, with a very influential and noisy father, played to a T by Broderick Crawford. It is taken as obvious that the Soviets have nabbed the son, but why?

Crawford flies to Berlin to show the paper-pushing bureaucrats how to get results in the real world! This he tells to newsmen whose circumspect replies tip off viewers to what will follow.

In this Berlin human beings are trafficked in all kinds of ways and this incident is another example of that. Nothing happens by chance. Everything connects, somehow, but how?

Crawford discovers a world where insistent bluster and big bucks do not matter one whit. No one wants his money and his bellows fall on deaf ears. Peck gives him a marvelous dressing down but Peter van Eyck does even better in an earlier and lower key scene in breaking the news that his big money and many friends mean nothing in this time and place.

Before he became Jed Clampett, Buddy Ebsen is a perfect chorus to Peck who is effortlessly glamorous and briskly decisive, while Ebsen is an ‘ah shucks a good ole boy,’ but one who knows how to get things done even in this dark and menacing place.

Much of the screen play is cryptic by today’s standards. It takes awhile to realise that the extraction is afoot, and the importance of that briefcase Peck constantly carries around slowly dawns. He carries it around, I inferred, because in it he has the most top secret confidential documents that he does not trust, even to a safe at HQ. It is always in his hand or always in his sight. Almost.

Since he is there, Peck insists that Crawford witness the proceedings. He does and it is an eye-opener for him, and a growth experience, though Crawford’s change of heart is a little too quick but the clock ticks relentlessly in this film, and if the final result is just a little too easy, it does wrap everything up with a mighty twist.

There is a lot of talk and virtually no action. In Hollywood terms that makes it cerebral and it would probably not be made today in this way. Most of it occurs in offices or rooms, with one scene in a bar and another at the loading dock of a hospital. One punch is thrown when Peck strikes a woman!

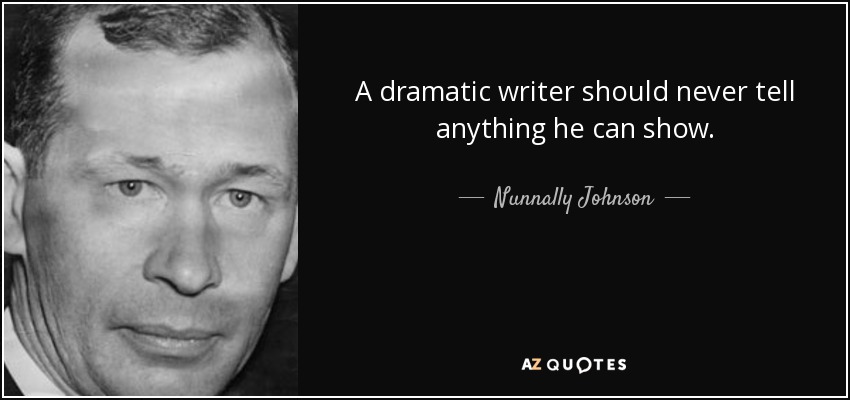

Nunnally Johnson (1897-1977) wrote the screenplay and it is a corker for its overall plot, its humanity, and dialogue.

If only…..

If only…..

Among his many other credits are ‘Grapes of Wrath’ (1939), ‘Tobacco Road’ (1941), ’The Moon is Down’ (1943), ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ (1953), and ‘The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit’ (1956). The themes in these films include that depression, corruption, oppression, anti-semitism, and racism, and then there is the delightful comedy of ‘How to Marry a Millionaire.’

The military parade at the beginning does drag on but to original audiences in 1954 it would have been reassuring, and it segues nicely into the plot. Original audiences would also have seen that both Peck and Ebsen wear uniforms with shoulder patches indicating combat service in World War II and both uniforms sport impressive ribbons betokening Silver and Bronze Stars. They have been in the shooting war.

I watched it on a DVD acquired from Amazon.

‘The Plant’ by Kit Brookman, Ensemble Theatre.

Performances until 5 August. Recommended.

A one act play of 90 minutes, this is a family drama. Three years ago Henry died in the garden and his widow-wife, Sue, soldiers on with her three adult children, Erin, Naomi, and Daniel. Sandy Gore as Sue carries the burden, and does so marvellously. The others are fine, but she is the centre around which they turn, albeit reluctantly.

Much is told in flashbacks to fill in the gaps.

Erin, Naomi, and Daniel have lives of their own and are too busy for more than brief and ritual visits to Sue, hastening in and out. Erin is the leader of the pack on some measures. She is married with two children, and a budding career as a literary agent. (Some knowing in jokes there from the playwright.) She has the least time for anyone else, the mobile phone constantly ringing, the off stage children demanding, the husband to be placated. Naomi, the youngest, is a drifting dreamer with pot smoking interfering with her work at the call center. Boy, does that explain a lot. While she is not pressed for time, well pot smoking keeps her busy. Daniel is on an upward trajectory at school, now department head. Poor sod. Daniel under constant pressure to mark papers, attend meetings, complete budget spreadsheets. He is in a relationship with Kim or is it Tim, I could not tell. Whatever the name, it is a man. They whirl individually in and out of Sue’s house.

She has found that she cannot communicate with them. Talk, yes, but communicate, no. It is partly their preoccupations that block the signal, but Sue also has trouble putting her thoughts and feelings into words. She is not quite sure what she wants to say, and that uncertainty together with their noise discourages her.

By chance she starts talking to a plant, as in the title, ‘The Plant,’ as a lonely person might talk to a pet, a dog. She finds that helps. As Georg Hegel would say, she objectifies her thoughts by speaking them into the world, and that is relaxing. It also helps her come to terms with the situation. Then she takes in a border, Clare, who takes the place of The Plant. See it to believe it.

This intruder rings alarm bells with the children who find enough time to chasten Sue, to warn her, to threaten the border, to spy on Sue.

By the end all three children are back at home. Erin was so successful that did not notice her husband’s departure until it was too late. Naomi has lost yet another job and spent all her dosh on dope when the rent is due. Tim/Kim splits from Daniel who is lost.

The play is the thing, and now that I know the name Kit Brookman, I want to see more. Though he looks like a child in the publicity photographs, the script has insights to go with the wit and zest.

The players live up to the words, and we loved Clare’s shoes.

The staging is minimal. A few cardboard boxes and one chair. When there is something to be said, few props are needed. Though there is Clare’s gear.

We drove to Kirribilli over the Bridge and parked on the street to see the play, and then had lunch there on a fine winter’s day, bright, clear, and 18C with views of the Harbour while we talked about what we had just seen.

‘On the Bone’ (2016) by Barbara Nadel

Inspector Cetin Ikmen and his team are back at it once more in the bazaar of Istanbul, awash with Syrian refugees and militant Islamic zealots under the watchful eyes of the security services.

A perfectly unremarkable and pleasant young man staggers to his death on the steps of a church, the victims of a heart attack. Case closed. Wait! Not quite, the routine autopsy accorded such an unexpected death produces a disturbing result.

Istanbul in full swing.

Istanbul in full swing.

Back and forth across Istanbul go Ikmen’s minions and the man himself. Getting nowhere, Ikmen, reluctantly recruits, a one-time criminal computer hacker to find wanna be cannibals on the dark web, fearing that he is giving matches to an arsonist.

Did the dead man knowingly and willingly eat human flesh? If so when, where, and how? If not knowingly or not willingly, what happened? In either case his dead body is itself a crime scene, and this causes the first difficulty because a good muslim is to be buried before the sun goes down. But in the circumstances no higher authority wants to rule on the technicality of what is a crime scene. Instead low level functionaries are left to their own devices.

Ah, how that reminds some of life in large, complex organisations full of self-styled leaders at the top who stay there, in part, by not leading. Does Max Weber cover this somewhere?

Ikmen’s efforts to get one of his superiors to declare the cadaver a crime scene bring out the worst in everyone. They go through the stages of bureaucratic grief when confronted with a career-threatening problem: first, denial. The pathologist must be wrong. But no, the tests are conclusive. Second, anger. Why bring this to me! It is someone else’s responsibility. Go away! But it is your problem as per the organisational chart. Third, bargaining. Let’s find a middle way. Keep the stomach and contents and release the rest of the body, but say nothing. Fourth, depression. One higher authority takes sick leave to avoid further involvement. Only Ikmen accepts the reality and the responsibility that comes with it, because he has no other choice. After all the human flesh consumed came from a victim, and he has to identify that victim and ascertain what happened.

Minor plots go swirling by. On street corners congregate idle young men who dream of martyrdom for Allah. Syrian refugees who cannot speak Turkish struggle to survive out of trash cans. Churches are bombed. Jewish cemeteries vandalised. Russian tourists are buying up property. Public works projects have stopped in mid-stride with the vicissitudes of the regime.

In distant Ankara members of the government seem more preoccupied with in-fighting than with governing. Another verity.

All the further testing done to discredit the finding of human flesh throws up another clue. The flesh has the genetic markers of a very rare disease that almost exclusively afflicts Jews. If the victim was Jewish the narrows the field of inquiry but strews it with social landmines when Ikmen has to seek out Jews. Is he insulting Turks by asking if they are Jewish or have Jewish ancestors? Is his a witch hunt for Jews on behalf of the regime? In the volatile world of contemporary Istanbul who wants to admit to being Jewish if it is an option not to do so.

Barbara Nadel

Barbara Nadel

While I found reading this novel uncomfortable, the ISIS martyrs in the making, the cannibalism, the clash of the Russian mafia with the local rivals, and all the innocents caught in the several crossfires, there is no doubting the author’s skill in putting it all together. The greater is the admiration when one realises this is the eighteenth Ikmen krimi. What an achievement to keep such a long running series fresh. Chapeaux!

When I entered this title onto the software I use to catalogue books the program fetched the metadata and the author came out as Brian Nadel! Wrong!

‘The Piano Cemetery’ (2010) by José Luis Peixoto

The Lázaro men are carpenters and in their workshop there is backroom, usually kept closed, full of broken down pianos – the cemetery of the title. That much I got. It is set in Lisbon.

José Luis Peixoto

José Luis Peixoto

It has been well reviewed in ‘The Times’ (London) and ‘The Financial Times,’ and it has many stars in Good Reads reviews. He has many other titles.

This is homework for our Iberian travels in the future.